Ruth Hull Chatlien's Blog, page 23

October 30, 2013

Writing Historical Fiction: Using (and Faking) Old Letters

As I mentioned the other day, Betsy Bonaparte’s life is well documented. Many of the biographies about her quote extensively from her letters, and I include excerpts of some of them in my novel.

But there were also times when I couldn’t find a letter that said what I needed for the story, so some of the letters in my novel are fictional, written by yours truly. Trying to imitate that nineteenth century style was an exceptionally enjoyable exercise.

Below are two different letters written from Betsy to her son Bo when she was in Europe and he was in the United States. One is authentic, the other is one of mine. (I’m not saying which is which.)

This first one was written when Bo is still a young boy:

Being separated by the Atlantic is as disagreeable to me as it is to you, but I must do what is necessary to secure your future. Reward all my cares for you by studying as hard as you can, so that when I come home I will find that you have proven yourself worthy of the Bonaparte name. I love you, and I shall not rest easy until I can be with you again and look after you myself.

This second one was written shortly after Bo has traveled along to America to begin his studies at Harvard:

I shall go to America if you think there is the least necessity for it. Let me know everything about my finances. Do read as much as you can, and improve in every way. I ask you to reward my cares and anxieties about you, by advancing your own interests and happiness. I am very uneasy about you, and almost blame myself for not going with you to take care of you, and shall never forgive myself if you meet any accident by being alone.

If anyone cares to guess which letter is which, I’ll post the answer in the comments sometime tomorrow.

October 29, 2013

The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte: Progress Report

I’ve finally turned in every last piece of The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte I need to send to production. The last two pieces to go were the table of contents and the back cover synopsis.

We have finalized the cover design. We did our interior design work weeks and weeks ago.

All the chapters have been poured. The designer says it’s looking good, and she has given me a page estimate. She’s also been sending me questions about the end matter. (I have to have a copyright page because of the real letters and documents I quote, plus I’ve included a bibliography of my main sources and a set of reader’s discussion questions.)

I haven’t heard yet what our projected publication date will be. However, the designer has been working much more quickly than I anticipated, and she’s supposed to send me PDFs of the book today or tomorrow.

I feel like I’m sledding down a hill, slightly out of control, with the wind rushing in my ears. Soon, very soon, I am going to be a published novelist. It still doesn’t seem real, but I guess the only thing to do at this stage is to enjoy the ride.

October 28, 2013

Thinking About Act Two

When I think about starting my next book, I find myself torn between two different ideas. I may do both eventually; the problem is in deciding the order.

The first idea–which I’ll call Cécile’s story—builds off some of the research I did for The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte (AMB). The time period and the locations are similar. The plot would be quite different. Unlike AMB, it wouldn’t be based on real people. The story I have in mind was inspired by the life of a couple of women I read about, but it diverges significantly from real events.

The second idea—which I’ll call Sarah’s story—is based on the memoir of a real woman caught in a real conflict. It is set in a different place and a later time period. I have a stack of books in my office that I purchased to research this particular event.

Pros and cons?

Both books would focus on women in time of war / conflict. Both deal with issues that intrigue me.

I suspect that Cécile’s story may be less commercial than Sarah’s, which has more action and more external conflict. If I wrote Cécile’s story next, I will likely get “branded” as someone who writes about one particular period and one particular set of locations. Since I don’t want that to happen, it might make more sense to do this as my third book.

I was actually intending to start Sarah’s story this fall. However, I need to take a research trip that, for reasons related to the plot, has to take place in summer. We intended to go in August but weren’t able to swing it because of our work schedules. That setback seems to have deflated whatever mojo I had for the project. I keep telling myself if I start the book research, the drive will come back, and then I can do the research trip (which mostly relates to setting details) next year. My inner muse remains stubbornly unconvinced.

For whatever reason, Cécile’s story is the one tugging at my imagination. It will require just as much research, but at this point, I’m not planning a trip to do any of it. Yet, I remain troubled by the suspicion that it doesn’t have the same marketable hook of Sarah’s story or AMB, for that matter. (I’m not totally sure of that though. I have thought of one idea that could ramp up interest in it.)

And so I dither and tell myself I’m just too busy with the last details of AMB and a too-full freelance schedule to start anything new.

One of these days soon, however, I’m going to have to make a decision and commit to it. Otherwise, I run the risk of AMB being an only child.

October 26, 2013

Research Photographs

In retrospect, I wish I had taken more photographs when I took my research trip to Baltimore. The ones I did take were so helpful.

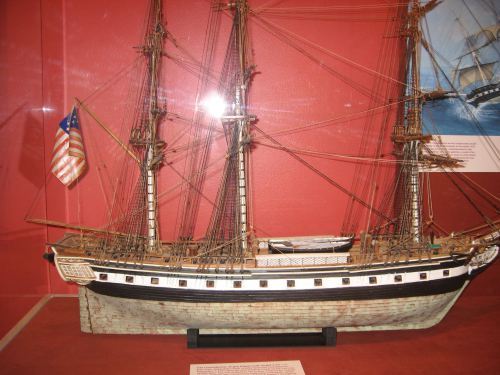

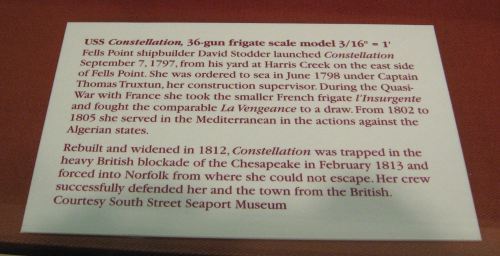

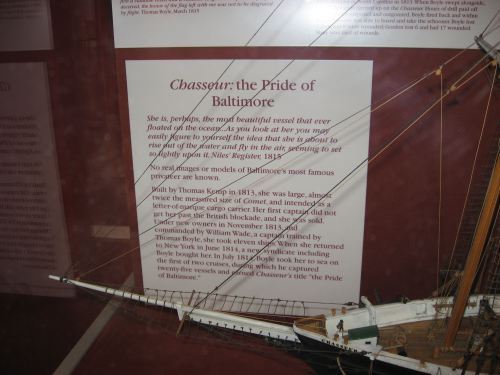

Here are a few more of the images I referred to as I wrote the novel:

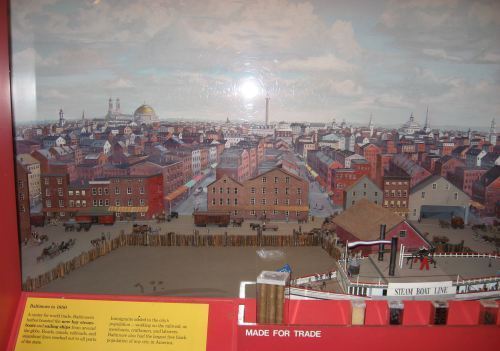

A Shipyard at Federal Hill, Baltimore

Baltimore, circa 1850

October 25, 2013

Book Review: Unravelled

I just finished reading the historical novel Unravelled by M.K. Tod. It has an interesting premise summed up by its log line: “Two wars. Two affairs. One marriage.”

The novel opens in 1935. Canadian veteran Edward Jamieson has received an invitation to go to France to commemorate the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Edward has struggled to overcome what we now call PTSD and later hidden his memories of the war from his wife Ann. So, he’s not eager to return to the place where he survived such horror. Yet, something else from his past—the memory of a passionate love he lost during the chaos of wartime—compels him to make the journey. What he finds in France leads to a marital crisis nearly as destructive as a battle.

Flash forward a few years to the eve of World War II. Although his age and permanent lung damage from the first war prevent Edward from signing up for active duty, he finds another way to serve his country—a way that must be kept secret from his family. Ann, in turn, finds herself struggling against loneliness, resentment, . . . and unexpected temptation. Is the Jamieson marriage strong enough to survive so many external stressors? That is the central question at the heart of this book.

The writing makes it evident that Tod did her research meticulously, yet she is judicious in her choice of details. Not once in the course of the book did I feel that she was piling on interesting facts just to show off her hard-earned knowledge. Tod also is unsparing in portraying the effect of war on families, but she avoids melodrama or maudlin sentimentality.

My biggest regret about the story is that I wanted to see what Ann and Edward were like together in happier times, before the decade of turmoil portrayed in this novel. In some of the conversations where they discuss their problems, they refer to what their relationship has lost. And they think things like, “I miss Ann’s sense of humor.” As a writer, I imagine that, in dealing with such an epic story, Tod had to make difficult choices about what to include in the plot. However, as a reader, I would have liked to have briefly glimpsed that more ideal time through a dramatic scene or two instead of having the characters tell me what they lost. Such scenes would have given me a sharper sense of the damage and raised my emotional stakes in the survival of the marriage.

I don’t mean to imply that I didn’t care about the characters. I did, and I felt compelled to continue with their story because I wanted to know what happened. Despite an exceptionally busy work schedule, I read the book in less than a week. It was also interesting to read a novel from the Canadian point of view. Most of the other novels I’ve read set during the two world wars have been told from a U.S., European, or Asian perspective.

Lovers of historical fiction, especially those interested in the two world wars, will find this a captivating story. The novel will also appeal to readers who like to explore the inner workings of a marriage. For these reasons, I recommend Unravelled without hesitation.

October 23, 2013

Writing Historical Fiction: Hanging the Swags

Photograph of Niagara Falls by Saffron Blaze, via Wikimedia Commons

One of my favorite analogies for writing historical fiction is “hanging the swags.” My novel The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte is about a real woman whose life is well documented. The Maryland Historical Society alone has something like eighteen boxes of letters, account books, and newspaper clippings relating to Betsy Bonaparte, and numerous biographies have been written about her. So I was working from a fairly clear outline consisting of the main events of her life. I think of those events as brackets extending at irregular intervals along a wall.

Even with as much as is known about Betsy, however, there are still gaps that required me to add material to connect the brackets. For me, one of the biggest holes was the lack of explanation for why Betsy and Jerome did some of the things they did.

Here’s a perfect example. After they had been married about a year, they decided to sail to France to try to obtain Napoleon’s approval of their marriage. The problem was that Jerome and Betsy were a celebrity couple, and much was written in the newspapers about them and their plans. The British, who were at war with France, were well aware that “Boney’s” baby brother wanted to get back home. The British decided that a great strategy would be to try to capture Jerome to hold him hostage. At one point, when Betsy and Jerome were planning to sail from New York on a French frigate, they learned that several British warships were hovering just beyond the narrow strait they would have to take to reach the Atlantic. Understandably, they decided not to risk it.

Here’s where the story gets weird. What did Jerome decide to do at this point when the very future of his marriage is on the line? He decided to take Betsy on a six-week excursion to visit the great falls at Niagara. At the time, 1804, Niagara was still an unsettled wilderness, not a kitschy honeymoon destination. As a general rule, only scientists and explorers went there. One thing that’s known about Jerome is that he believed it was important to see the major sites whenever he visited a country so he wouldn’t appear “stupid” later when people asked him about his trip. A reason like that is sufficient in a biography. In a novel, not so much. I didn’t want my readers to stop and think, “What a dope. I’d never have done that.”

So what did I do? I made up a fictitious event that would give Jerome a plausible reason for thinking that Betsy’s nerves have been overtaxed by the strain in which they were living. The trip becomes much more sympathetic if it is undertaken in an effort to reduce Betsy’s stress and improve her health.

And that’s what I mean by hanging the swags. I started with two historical events that were my “brackets”: the decision not to try to break the British blockade and the subsequent, unexplained decision to travel to Niagara. As a novelist, I connected the two with a “swag”—a linking episode of my own creation. Coming up with that filler material was one of my favorite parts of writing the novel

October 22, 2013

19th Century Life: Visiting Cards

Yesterday, as I was making breakfast, I found myself thinking about the 19th century custom of leaving visiting cards. I’m not an expert, but as I understand the custom, when two people had a mutual acquaintance or perhaps met casually at a social function, the visiting card was a way to check out whether they might develop a relationship. The scenario went something like this:

Mrs. Hopewell called on the home of Mrs. Fotheringale and left a card with a servant.

If Mrs. Fotheringale was interested in pursuing the acquaintance, she would call on the home of Mrs. Hopewell and leave a card.

Then Mrs. Hopewell would know that if she called on Mrs. Fotheringale during visiting hours, she would be admitted into the house.

And Mrs. Fotheringale could call on Mrs. Hopewell.

Thus, a social acquaintance was established.

I see a contemporary parallel in blogging, don’t you? I stop by a new blog, and “like” a post. The blog owner might then come by here and “like” a post. I visit his blog again and leave a comment. He might return the favor. Then we decide to follow each other’s blogs.

As they say, the more things change, the more they stay the same, n’est-ce pas?

October 21, 2013

Publishing: Working with Good People

I turned over the manuscript to the designer at the end of the day Friday. She and I have already made all the decisions abut the interior design, so she was able to start working on the layout first thing Saturday.

She e-mailed me mid morning to ask about a possible editorial mistake. In the second chapter, one character’s age was listed as “41″ instead of the age being written out as all the other ages are. She asked if she should change it, and I said, “Yes, please.”

I can’t tell you how many times I have read this book, and it’s been through copy editing, yet the mistake still slipped through.

You would think I would feel really discouraged about that, but I’m not. Instead, my instantaneous reaction was gratitude. I count myself blessed to be working with a designer who would notice something like that. Not all do; it’s not their job. But this one did, so once again, I feel reassured that my baby is in very good hands.

October 19, 2013

Deleted Scenes

Today I’m going to post something a little bit different, just because I can.

One of my favorite features on DVDs of hit movies is to watch the deleted scenes and debate with my husband whether the director made the right decision. Almost always, we agree.

Well, today, I’m going to post a scene from The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte that was deleted from the final version. It’s based on a real incident in Betsy and Jerome’s life, but it distracted too much from the big picture of what was happening at that moment. Its purpose was to show Betsy’s courage, but that’s demonstrated far more effectively later through more dramatic events (such as a shipwreck). The main point of the chapter in which this appeared was something quite different, and this scene didn’t contribute to that, so I cut it. It was not an easy decision because I liked the scene, but writers have to make these choices sometimes. Now that I have a blog, I can get some use out of the scene after all.

First let me provide a little background. They’ve been married only a month. It’s winter, 1804. Jerome decides they should travel to Washington, D.C., to visit some of Betsy’s relatives, dine with President Jefferson, and generally have a good time. (Jerome was big on having a good time.) Note that when Jerome uses the name Elisa, he means Betsy. It was his pet name for her.

The forty-five-mile trip from Baltimore to Washington was an all-day journey through much undeveloped country. Because it was winter, darkness fell long before they reached the city. As they approached the outskirts of the capital, Betsy dozed off with her head against Jerome’s shoulder. Suddenly, the carriage jolted over a bump and, as Betsy jerked awake, she heard a man’s cry outside. Jerome pulled up the curtain on the nearest window and called to the coachman, “What is wrong?”

No answer came, so Jerome put his head out the window and then quickly pulled it in again. “Mon dieu, we have no driver. I must leap out and try to stop the horses.”

“No, you might be hurt!” Betsy grasped his arm.

“Elisa, we have no choice. If the horses are not stopped, the carriage could overturn.”

Jerome shed his cape to avoid the risk of its being caught in the wheels and then opened the door and leaped from the vehicle. Moving to the opening, Betsy saw him spring up and run after the carriage, which was starting to slow down. Putting on a burst of speed, Jerome passed the carriage and came alongside the team.

Holding the doorframe, Betsy leaned out enough to see him reach for the bridle of one of the lead horses. To her horror, Jerome slipped on the snowy road but managed to throw himself away from the pounding hooves as he fell. As the carriage drove by his prostrate figure, Betsy heard him call her name.

The carriage was about to pass a large snowdrift beside the road. On impulse, Betsy sprang through the door, landing on her hands and knees in the snow.

For an instant, she could not breathe, and Betsy feared that she had injured herself. Then, pushing herself over onto her back, she inhaled with a great gasp. As nearly as she could tell, her bones were unbroken and she began to laugh with giddy relief.

A moment later, Jerome ran up, speaking so rapidly in French that Betsy could not understand him. He knelt and took her in his arms, and she saw by the light of the moon that he was crying. “My God, I thought I had lost you.”

The coachman ran past them, shouting at the horses, which were a long way down the road but heading toward a lighted building.

“That fool of a driver must have fallen asleep. I will beat him for his negligence.”

“No, darling.” Betsy took off her glove and laid a hand on his cheek. “We are both safe. Providence looked after us, and that is all that matters.”

“When I consider that you might have been killed, I feel wild with rage.”

“Think of it as an adventure. I am quite exhilarated,” she said and laughed again.

Jerome shook his head. “My God, you are a remarkable woman.”

October 18, 2013

Writing Historical Fiction: Using Figurative Language that Adds to the Historic Setting

One of the things I tried to do while writing The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte was to choose metaphors and similes that were appropriate for the time period and the background of my characters. It became an interesting challenge.

For example, Betsy’s father, William Patterson, was a wealthy merchant who was active in the shipping business. During one scene in which Betsy and her father were arguing about her relationship with Jerome Bonaparte, I had Betsy exclaim, “Jerome is not shipment of spoiled cargo to be deducted from my ledger!” The metaphor fits because she is talking to her father in language he will understand.

Similarly, I used figurative language that drew upon the domestic lives of the female characters. Early in the book, Betsy’s Aunt Margaret says to her mother, “Dorcas, you look unwell. You are as white as my linen shift.”

And in one of my favorite passages, I combined domestic imagery with Betsy’s infamous sharp tongue:

Despite her plain looks, Mrs. Merry was dressed as a beauty with rouge on her cheeks and a chandelier necklace of sapphires around her throat. Her blue velvet gown was cut so low that her enormous bosom, restrained only by a film of lace, threatened to pop free. As soon as they were out of earshot of the Merrys, Betsy whispered to Jerome, “Law, she displays those melons as though she were a market.”

Sometimes, I used comparisons that were drawn upon the characters’ past lives. For instance, I had to come up with a simile to describe Betsy’s impatience. She and Jerome have been waiting to hear whether the Bonapartes approve of their marriage. As they’re visiting friends in New York, they receive a letter from Betsy’s father telling them to come home. Word has just arrived from France. This is how I described Betsy’s reaction to the four days it took them to return to Baltimore:

Even so, Betsy chafed at the length of the trip. While she appreciated her father’s discretion, given how frequently mail was opened and read in transit, she was desperate to know how the Bonapartes had reacted to her marriage. For the entirety of the journey, her curiosity was an itch akin to the torment she had suffered as a child whenever she got chigger bites from walking in wet summer grass on her family’s country estates.

Even when making quick comparisons, I tried to use period-appropriate details, as in the following sentence: “Betsy narrowed her eyes but kept her tone as sweet as marzipan.”

Of course, not every instance of figurative language is quite that period specific. Sometimes I just had fun using comparisons that work in any time period:

Uncle Smith shook his head. “Do not be so quick to applaud Bonaparte. Rumor is that he plans to create an American empire out of the Caribbean islands and the lands west of the Mississippi. And once he accomplishes that grand design, what will stop him from swallowing the United States as little more than a tasty sweet at the end of an enormous meal?”