Kevin Rutherford's Blog, page 7

August 25, 2013

The trouble with passwords

Recently I’ve been using other people’s computers a lot more often, because I’m working away from my home office most of the time. And because of this I noticed a serious flaw in the strategy I had used for choosing passwords: they were all the same! I had chosen a very strong password that was unguessable and yet memorable to me, but I had used it everywhere. So if anyone did ever guess it I would be screwed.

Time to change to a new strategy, I thought. So I looked at lastpass, 1password et al. But again, it seemed to me that I would ultimately be putting my entire faith in a single password (and a single supplier), which felt almost as unsafe as having the same password everywhere. So what to do? I need passwords that are strong, easy for me to remember, and different on every service I use. Oh, and they have to meet all the different and daft criteria that the various websites impose; some insist on at least 8 characters, some on at least 9; some insist on at least one digit; others require a capital letter; etc etc.

The only scheme I know of that meets all of these criteria is to use a memorable 2-3 word phrase, together with a keyword indicating the site holding the account. So I wrote a random phrase generator, and discovered that every ten refreshes or so I was pretty much assured of generating a phrase that stuck in my brain. (Unfortunately you then also need to sprinkle the password with numbers and punctuation, not to make it stronger but to meet those daft website rules.)

For example, I just ran the generator and got bloody tomato. So I might then use the different passwords Blo0dy-tomato+mates for facebook, Blo0dy-tomato+pic for instagram, etc. As long as the scheme for adding the site-specific key is personal and memorable this should be a better password strategy than I had before.

Feel free to use the generator yourself (but obviously I can’t be held responsible if your passwords are hacked). The current words lists can generate over 750 trillion different passphrases, and I’m adding more words all the time.

May 14, 2013

Query actions in Rails controllers

Recently some of my controller actions have taken on a definite new shape. Particularly when the action is a read-only query of the app’s state. Such actions tend to make up the bulk of my apps, and they can be simple because they are unlikely to “fail” in any predictable way. Here’s an example from my wiki app:

This has a couple of significant plus points: First, no instance variables, so both the controller action and the view are more readable and easier to refactor. Second, no instance variables! So there’s a clear, documented, named interface between the controller and the view. And third, this is so transparently readable that I never bother to test it.

The wiki used in the above action is a repository, built in a memoizing helper method that most of the controllers use:

In this case the correct kind of repository is created for the current user, and all of the other code in this request sits on top of that. So the controller action, helped by the memoized repository builder, effectively constructs an entire hexagonal architecture for each request, and the domain logic is thus blissfully unaware of its context.

Here’s a slightly bigger example. This is for a page that shows a variety of informative graphs about the wiki; and because I may want to re-organise my admin pages in the future, each graph’s data is built independently of the others:

That’s the most complex query controller action I have, and I maintain that it’s so simple I don’t need to test it. Would you?

January 30, 2013

Why shorter methods are better

TL;DR

Longer methods are more likely to need to change when the application changes.

The Longer Story

Shorter methods protect my investment in the code, in a number of ways.

First: Testability. I expect there to be a correlation between method length (number of “statements”) and the number of (unit) test cases required to validate the method completely. In fact, as method size increases I expect the number of test cases to increase faster than linearly, in general. Thus, breaking a large method into smaller independent methods means I can test parts of my application’s behaviour independently of each other, and probably with fewer tests. All of which means I will have to invest less in creating and running the tests for a group of small methods, compared to the investment required in a large method.

Second: Cohesion. I expect there to be a strong correlation between method length and the number of unknown future requirements demanding that method to change. Thus, the investment I make in developing and testing a small method will be repaid countless times, because I will have fewer reasons in the future to break it open and undo what I did. Smaller methods are more likely to “stabilize out” and drop out of the application’s overall churn.

Third: Coupling (DRY). I expect that longer methods are more likely to duplicate the knowledge or logic found elsewhere in the same codebase. Which means, again, that the effort I invest in getting this (long) method correct could be lost if ever any of those duplicated pieces of knowledge has to change.

And finally: Understandability. A method that does very little is likely to require fewer mental gymnastics to fully understand, compared to a longer method. I am less likely to need to invest significant amounts of time on each occasion I encounter it.

The Open-Closed Principle says that we should endeavour to design our applications such that new features can be added without the need to change existing code — because that state protects the investment we’ve made in that existing, working code, and removes the risk of breaking it if we were to open it up and change it. Maybe it’s also worth thinking of the OCP as applying equally to methods.

January 18, 2013

A testing strategy

The blog post Cucumber and Full Stack Testing by @tooky sparked a very interesting Twitter conversation, during the course of which I realised I had fairly clear views on what tests to write for a web application. Assuming an intention to create (or at least work towards creating) a hexagonal architecture, here are the tests I would ideally aim to have at some point:

A couple of end-to-end tests that hit the UI and the database, to prove that we have at least one configuration in which those parts join up. These only need to be run rarely, say on CI and maybe after each deployment.

An integration test for each adapter, proving that the adapter meets its contract with the domain objects AND that it works correctly with whatever external service it is adapting. This applies to the views-and-controllers pairings too, with the service objects in the middle hexagon stubbed or mocked as appropriate. These will each need to run when the adapters or the external services change, which should be infrequent once initial development of an adapter has settled out.

Unit tests for each object in the middle hexagon, in which commands issued to other objects are mocked (see @sandimetz‘s testing rules, for which I have no public link). And for every mocked interaction, a contract test proving that the mocked object really would respond as per the mocked interaction (see @jbrains‘s Integrated tests are a scam articles). These will be extremely fast, and will be run every few seconds during the TDD cycle.

I’ve never yet reached this goal, but that’s what I’m striving for when I create tests. It seems perfectly adequate to me, given sufficient discipline around the creation of the contract tests. Have I missed anything? Would it give you confidence in your app?

November 4, 2012

I’m growing a mo

Two years ago the fantastic staff at Macclesfield hospital saved my life. To cut a long story short, my colon burst due to diverticular disease; Mr Khan and Mr Hadjiloucas correctly diagnosed it and operated in the nick of time. (Seriously. Two hours later and I would have been gone.) I had two 6-hour operations 5 months apart, and received superb care from all the staff involved during that period.

So I feel it’s the least I can do to raise a little money to help the hospital. And that’s why, in an event that runs spookily parallel to Movember, I’m growing a moustache for money. Your money. Please help the hospital by giving a little at my JustGiving page, or by telling everyone you know and raising my mo’s profile. Thank you.

September 3, 2012

The problem with code smells

Like most developers I know, I have used code smells to describe problems in code since I first heard about them. The idea was introduced by Kent Beck in Fowler’s Refactoring back in 1999, and has taken root since then. The concept of code smells has several benefits, not least the fact that it gives names to ideas that were previously only vague. Having a list of named code quality anti-patterns helps all of us discuss them on the same terms.

But while I was writing Refactoring in Ruby with @wwake, and writing Reek at the same time, I began to feel a little uneasy about them. I was never able to put my finger on exactly why that was, or what I was uneasy about, but the feeling never went away. This year I think I have finally understood what I think about code smells, and why I think we can do somewhat better. So before reading on, take a moment to list the things you don’t like about them. Then let’s compare lists. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

Ok, done that? Here are my current reasons for wanting a different tool for describing code quality:

The names aren’t all that helpful for people unfamiliar with the concepts. If you had never heard of them, what would you make of Feature Envy, Shotgun Surgery, Data Clump etc? Sure, the names are memorable, but that only helps with hindsight, for people who have taken the time and trouble to investigate and learn them.

Some code smells can overlap. For example, I’m often unsure whether I have seen Feature Envy or Inappropriate Intimacy, Divergent Change or Large Class. There’s a sense in which this doesn’t matter, of course; but it undermines their use as a communication tool.

Some of the smells can be subjective or contextual, leaving the quality of the code open to interpretation. For example, how large is a Large Class or a Long Parameter List?

Some of the smells apply only under certain circumstances. For example, a Switch Statement is perfectly fine at the system boundary when we are figuring out the type of an incoming message, but often bad news when it represents a type check on code we own. And it can be acceptable at the system boundary to grab the fields of a Data Class in order to display them, while elsewhere that might be seen as Feature Envy.

The list of code smells is not canonical; different people have added their own smells to Beck & Fowler’s original list. This situation is even worse when it comes to smells in unit tests; try looking for a canonical list of test smells and you’ll find no consensus whatever. In my opinion, this fact alone completely undermines the idea that code smells form a pattern language for describing code quality.

There are no clear and obvious code smells covering some dynamic problems, such as the coupling between variables whose values depend on each other, or the problems introduced by mutable objects.

Did you have the same list, or something similar?

So, what can we do about it? I think the answer lies with Connascence. This is an idea introduced by Meilir Page-Jones in two books in the 1990s, and later popularised by @jimweirich in a series of conference talks. I’m not going to cover Connascence in detail here — you can find it all for yourself by reading @jimweirich‘s articles or looking at my summary slides. I just wanted to take a moment to write down my current opinions about code smells. I’ll probably write in more detail about Connascence in the coming weeks, but for now what do you think?

July 11, 2012

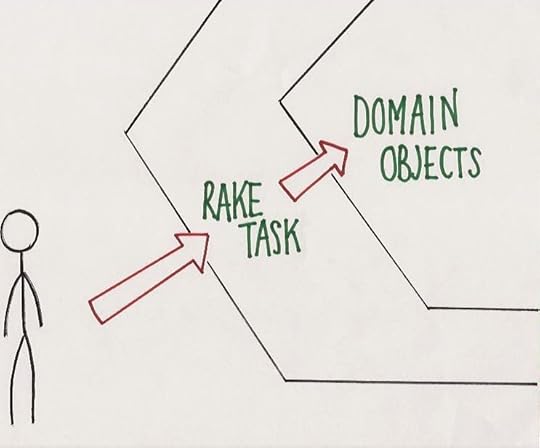

Hexagonal rails: Rake tasks are adapters

If I’m thinking about my Rails app in terms of a hexagonal architecture, I find it also pays to consider every rake task to be an Adapter. Thus:

Picture: @rosieemackenzie

The true picture is a little more complicated than that, but the principal ideas are there. The rake task acts as a mediator, allowing me to send messages to (ie. call methods on) my application’s objects.

In general, we want our Adapters to be as thin as possible (and no thinner). That’s because the Adapter code inherently depends on some framework, and that fact will usually make its tests difficult and/or slow. We still need those tests, but we want to have as few paths through the Adapter as possible, and thus fewer tests of the Adapter, so that the total test complexity and test run-time are minimized.

As an example, suppose I have a rake task that validates the posts and comments on my blog:

I want to maximize the unit tested percentage of the code executed during the task, so I move the code out of the rake task and into a new domain object. That new object “is” the task, and usually my rake tasks can then slim down to a single line of code.

Stripping all of the code out of the rake task and moving it into a domain object is analogous to the approach currently being explored by @mattwynne and @tooky in their Rails controller refactorings. In my own code I call these task objects “use case objects”. Currently I keep them in a UseCases namespace within app/models, although I’m open to exploring alternative conventions. One of the nice side-effects of this is that I sometimes discover synergies between the work done by rake tasks and that done by controllers. By pulling Use Case objects out of both kinds of adapter I’m creating a convention for some of the code that turns out to be cleaner, more (quickly) testable, and which names things better.

Please let me know if you try this — or indeed if you’re already doing it.

July 6, 2012

Hexagonal rails: Hiding the finders

This is a brief follow-up to the Hexagonal Rails sessions I did last week at the Scottish Ruby Conference with Matt and Steve. We tried to cram a 3-day course into 45 minutes, with inevitable consequences. So by way of an apology, here’s another brief foray into some of the same territory…

Today I’ve been exploring ways of improving the unit tests in one of my Rails apps. Let’s pretend it’s a blog app, and I have to add a feature to publish posts. I’ve pulled some code out of a controller to make a UseCase object:

(Here ui is a controller, and makes decisions about routing and rendering in response to the events sent by the use case object.)

I’m really sick and tired of looking at code like this. It seems that most of the classes in any Rails app know that finders return nil when they can’t find something, and so they all have to cope with that case. I want to get rid of that if, or at least hide it away in a single place so that it doesn’t contaminate the rest of the app. I want the test to be a bit simpler and more readable too. And I want the option to have richer finders, maybe coping with fuzzy edge cases and still finding the desired database record. In short, I want to wrap the finder in an Adapter.

So I experimented with a couple of alternatives to the above. First, a variant on Smalltalk’s ifTrue:ifFalse message argument style:

I don’t like this because it’s near impossible to isolate and test the interactions. For example, Blog.should_receive(:lookup_post).with( … what?

Another approach might be something like this:

Indeed Rails itself uses this style in its controllers, and so does the inherited_resources gem. But it suffers from the same testing problems as my previous attempt. So I finally settled on this:

This version uses an explicit listener object, which I can thus instantiate and test independently of the calling context. (In real code I might make it an inner class too.) And I’ve already found a couple more uses for the lookup_post method, removing dependencies and ifs along the way.

I find this approach highly readable and testable, nicely separating different responsibilities and allowing me to give them names. But that doesn’t mean I’ll stop exploring. Have you tried other approaches? How did they work out?

Update

Luke points out that I forgot to include the option I actually use the most, the Self Shunt:

This is the same as the listener option above, but the UseCase object passes itself as the listener, thus saving a class and in my opinion) improving readability a little. Can’t think why I forgot it, cos it’s the best and neatest of them all. Anyroadup, thanks Luke!

December 23, 2011

The wrong duplication (reprise)

I came across this old post again today, and I still like what it has to say: The Wrong Duplication. Maybe I should add a code example…?

November 16, 2011

Global Day of Coderetreat

In case you hadn’t noticed, XP-Manchester is running a Coderetreat as part of the Global Day of Coderetreat on December 3rd 2011.

You can find out everything you need to know by visiting our page on Eventbrite, where you can find FAQs, links to further information, and the all-important sign-me-up button. Oh, and it’s FREE to attend.

Places are limited, and tickets are going fast now, so make sure you book your place soon!

Kevin Rutherford's Blog

- Kevin Rutherford's profile

- 20 followers