Matt Ridley's Blog, page 42

January 7, 2014

The real risks of cherry picking scientific data

My Times column is on the dangers of omitting

inconvenient results:

Perhaps it should be called Tamiflugate. Yet the

doubts reported by the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee

last week go well beyond the possible waste of nearly half a

billion pounds on a flu drug that might not be much better than

paracetamol. All sorts of science are contaminated with the problem

of cherry-picked data.

The Tamiflu tale is that some years ago the pharmaceutical

company Roche produced evidence that persuaded the World Health

Organisation that Tamiflu was effective against flu, and

governments such as ours began stockpiling the drug in readiness

for a pandemic. But then a Japanese scientist pointed out that most

of the clinical trials on the drug had not been published. It

appears that the unpublished ones generally showed less impressive

results than the published ones.

Roche has now ensured that all 77 trials are in the public

domain, so a true assessment of whether Tamiflu works will be made

by the Cochrane Collaboration, a non-profit research group. The

person who did most to draw the world’s attention to this problem

was Ben Goldacre, a doctor and writer, whose book Bad Pharma accused the industry of

often omitting publication of clinical trials with negative

results. Others took up the issue, notably the charity Sense About

Science, the editor of the British Medical Journal

, Fiona Godlee, and the Conservative MP Sarah Wollaston. The

industry’s reaction, says Goldacre, began with “outright denials

and reassurance, before a slow erosion to more serious

engagement”.

The pressure these people exerted led to the hard-hitting PAC report last week, which found

that discussions “have been hampered because important information

about clinical trials is routinely and legally withheld from

doctors and researchers by manufacturers”.

The problem seems to be widespread. A paper in the BMJ in 2012 reported

that only one fifth of clinical trials financed by the US National

Institutes of Health released summaries of their results within the

required one year of completion and one third were still

unpublished after 51 months.

The industry protests that it would never hide evidence that a

drug is dangerous or completely useless, and this is probably so:

that would risk commercial suicide. Goldacre’s riposte is that it

is also vital to know if one drug is better than another, say,

saving eight lives per hundred patients rather than six. He puts it this way: “If there are eight people

tied to a railway track, with a very slow shunter crushing them one

by one, and I only untie the first six before stopping and awarding

myself a point, you would rightly think that I had harmed two

people. Medicine is no different.”

Imbued as we are with an instinctive tendency to read meaning

into nature, we find it counter-intuitive that many experiments get

significant results by chance and that the way to check if this has

happened is to repeat the experiment and publish the result. When

the drug company Amgen tried to replicate 53 key studies of cancer,

they got the same result in just six cases. All too often

scientists publish chance results, or “false positives”, like

gamblers or fund managers who tell you about winners they

backed.

Outside medicine, we popular science authors are probably guilty

of too often finding startling results in the scientific literature

and drawing lessons from them without waiting for them to be

replicated. Or as Christopher Chabris, of Union College in

Schenectady, New York, harshly put it about the pop-psychology author Malcolm

Gladwell: cherry-picking studies to back his just-so stories. Dr

Chabris points out that a key 2007 experiment cited by Gladwell in

his latest book, which found that people did better on a problem if

it was written in hard-to-read script, had been later repeated in a

much larger sample of students with negative results.

To illustrate how far this problem reaches, a few years ago

there was a scientific scandal with remarkable similarities, in

respect of the non-publishing of negative data, to the Tamiflu

scandal. A relentless, independent scientific auditor in Canada

named Stephen McIntyre grew suspicious of a graph being promoted by

governments to portray today’s global temperatures as warming far

faster than any in the past 1,400 years — the famous “hockey stick”

graph. When he dug into the data behind the graph, to the fury of

its authors, especially Michael Mann, he found not only problems

with the data and the analysis of it but a whole directory of

results labelled “CENSORED”.

This proved to contain five calculations of what the graph

would have looked like without any tree-ring samples from

bristlecone pine trees. None of the five graphs showed a hockey

stick upturn in the late 20th century: “This shows about as vividly

as one could imagine that the hockey stick is made out of

bristlecone pine,” wrote Mr McIntyre drily. (The bristlecone pine

was well known to have grown larger tree rings in recent years for

non-climate reasons: goats tearing the bark, which regrew rapidly,

and extra carbon dioxide making trees grow faster.)

Mr McIntyre later unearthed the same problem when the hockey

stick graph was relaunched to overcome his critique, with Siberian

larch trees instead of bristlecones. This time the lead author,

Keith Briffa, of the University of East Anglia, had used only a small sample of 12 larch trees

for recent years, ignoring a much larger data set of the same age

from the same region. If the analysis was repeated with all the

larch trees there was no hockey-stick shape to the graph.

Explanations for the omission were unconvincing.

Given that these were the most prominent and recognisable graphs

used to show evidence of unprecedented climate change in recent

decades, and to justify unusual energy policies that hit poor

people especially hard, this case of cherry-picked publication was

just as potentially shocking and costly as Tamiflugate. Omission of

inconvenient data is a sin in government science as well as in the

private sector.

Post-script:

This column is not mainly about climate change, but about the

ubiquitous problem of selective citation of data. As I said, we all

do it to some extent, but it is still a sin against statistics.

However, as usual when publishing anything that touches on climate

change, there has been an immediate and highly misleading attempt

to rubbish the work I reported and to imply that I am evil for even

reporting others' opinions that climate scientists, unlike all

other scientists, might not all be infallible. This touchiness is

quite striking and not reassuring. For those who wish to know the

full story of bristlecones and Siberian larch, please follow the

links in the piece, one of which is to a Guardian article, and

please note that this article reports what one of Professor

Briffa's colleagues had to say in an email not intended for

publication:

"In October last year, Briffa's old boss at CRU, Tom Wigley,

said in an email to Briffa's current boss Phil Jones: "Keith

does seem to have got himself into a mess." Wigley felt Briffa

had not answered McIntyre's charges fully. "How does Keith explain

the McIntyre plot that compares Yamal-12 with Yamal-all? And how

does he explain the apparent 'selection' of the less

well-replicated chronology rather than the later (better

replicated) chronology?... The trouble is that withholding data

looks like hiding something, and hiding something means (in some

eyes) that it is bogus science that is being hidden."

There has been a subsequent attempt to justify the selectivity

of the larch data, but it is not very convincing, and I recommend

McIntyre's ripostes to it here, here and here. The rich irony is that one of Briffa's

justifications for ignoring one of the larger samples is that it

contains "root collar" tree samples. This is exactly equivalent to

the strip-bark problem that leads McIntyre and the National Academy

of Sciences to reject the inclusion of “strip-bark” bristlecones in

temperature reconstructions - that they give a false signal. They

cannot have it both ways.

Leave the last word on this business to McIntyre, discussing

Briffa’s explanation for why we should all ignore the fact that

tree rings inconveniently show a decline in temperatures in recent

years, or “hide the decline”:

“You’ll probably roll your eyes at the following Briffa-ism used

to rationalize Hiding the Decline:

‘In the absence of a substantiated explanation for the decline,

we make the assumption that it is likely to be a response to some

kind of recent anthropogenic forcing. On the basis of this

assumption, the pre-twentieth century part of the reconstructions

can be considered to be free from similar events and thus

accurately represent past temperature variability.’

When I first encountered this, I could not believe that

credentialed scientists could either write such bilge. That the

authors of such bilge should be among the most respected members of

the field was even more unbelievable.”

There is an even more shocking story of data omission in the

manufactured attempt to claim a 97% consensus among scientists on

dangerous man-made climate change. As Jo Nova details here, the conclusion was based

on just 0.3% of the data:

"Of nearly 12,000 abstracts analyzed, there were only 64 papers

in category 1 (which explicitly endorsed man-made global warming).

Of those only 41 (0.3%) actually endorsed

the quantitative hypothesis as defined by Cook in

the introduction."

Post-script 2:

The Times published a letter from the UK chief scientist and the

head of the UK Met Office, which rather misrepresented what I said,

while conceding my main point - that climate science had not been

sufficiently transparent:

Sir,

Matt Ridley falls into his own trap in his Opinion column (

Jan 6), though the title “Roll up: cherry pick your research

results here” is apposite, because that is exactly what Ridley does

with respect to the research evidence for global warming.

There can be no sensible arguments against making available the

results of properly conducted research for open scrutiny. The

arguments for this have been rehearsed very effectively in health —

and, in general, the biomedical research community has accepted

these arguments. Indeed UK scientists pioneered the controlled

clinical trial and the Cochrane Collaboration led the way in the

rigorous meta-analysis of all sources of evidence to reach the most

reliable conclusions allowing the implementation of

“evidence-based” medicine. The pharmaceutical industry, which can

certainly be criticised for past practices in not revealing the

results of all clinical studies of new drugs, is now moving towards

greater transparency, and drug regulators, such as the EMEA, are

rightly pressing hard. Iain Chalmers, Ben Goldacre and others

deserve much credit for their campaigning for openness.

The same can be said of the climate science community. Following

the controversy over leaked University of East Anglia emails there

have been substantial efforts in making source data openly

available. It is partly through this openness and replicablility of

findings by researchers in different institutes the Berkeley Earth

Island Institute analysis published last year is a case in point—

that drew the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to the

unassailable conclusion in its most recent report that “warming of

the climate system is unequivocal”.

This report was a consensus led by 259 scientists, from 39

countries, which assessed the findings of all of the relevant,

peer-reviewed scientific literature published between the previous

report in 2007 and March of last year. Would that Matt Ridley

applied the same rigour when it comes to evidence about the

anthropogenic contribution to climate change. The “hockey stick”

graphs, prominent as they were at the time, are just one small part

of a massive global research effort that provides consistent and

overwhelming evidence.

Sir Mark Walport, Chief Scientific Adviser to HM Government

Professor Stephen Belcher, Head of Met Office Hadley Centre

My reply was as follows:

Dear Mark and dear Professor Belcher,

I am glad to see you recognising in your letter to the Times the

need for science, as well as industry, to clean up its act

with respect to transparency and data withholding. As for

the argument relating to the hockey stick that

"following the controversy over leaked University of East Anglia

emails, there have been substantial efforts to make source data

openly available", it is good that you acknowledge the role that

Climategate played in sparking this improved transparency.

Indeed, the surmise by Stephen McIntyre of Climate Audit that the

University of East Anglia had failed to report a Yamal regional

chronology that did not have a Hockey Stick shape was an important

issue leading into Climategate. Yet it was not investigated by

any of the East Anglia inquiries. As McIntyre says, "The existence

of this unreported adverse result was only revealed by subsequent

Freedom of Information requests - requests that were fiercely

resisted by the University." It was wrong that

those interested in understanding the hockey sticks had

to resort to freedom-of-information requests to get publicly funded

data that should have been freely published and wrong that the

requests were resisted.

You might be interested in McIntyre's account (to me) of what

has happened since: "In 2013, four years after the Climate Audit

criticisms, Briffa and coauthors published a re-stated version of

their Yamal chronology with a much diminished blade from the

previous superstick. Rather than "discrediting" the earlier

criticisms, the re-statement implicitly conceded the validity of

the earlier criticism, as shown by the measures taken by Briffa and

coauthors to avoid repetition of the earlier mistakes. While

they have avoided some of their earlier errors, their new

attenuated chronology still contains important methodological

defects and errors, as discussed at Climate Audit. Nor should

much weight be given to findings of the Muir Russell panel. Muir

Russell did not even attend the only interview with CRU academics

on the Hockey stick. Nor did the panel interview CRU critics.

Nor did the Muir Russell panel even ask Briffa and Jones about

their destruction of documents to evade FOI requests."

You then go on to say that global warming is unequivocal, with

which I entirely agree (if we take a 30-50 year period) though it

is the evidence, not the number of scientists who have put their

name to a report, that convinces me. (It is equally unequivocal

that warming has been slower than the models forecast.) But this is

a straw man. My article did not claim that the hockey stick was

necessary to prove the warming unequivocal. "Unequivocal" is not

the same as "Unprecedented", which was the claim made by the

hockey-stick graphs. So I did not "fall into my own

trap". May I urge you in future to address the actual

arguments of sceptics rather than the almost entirely mythical

claim that they think climate change does not happen.

Best wishes

Matt

January 2, 2014

The Anglosphere's long shadow

My Times column of 30 December 2013:

It was only five years ago that “Anglo-Saxon”

economics was discredited and finished. Continental or Chinese

capitalism, dirigiste and heavily regulated, was the future. Yet

here’s the Centre for Economics and Business Research last week

saying that Britain is on course to remain the sixth or seventh

biggest economy until 2028, by when it is poised to pass Germany,

mainly for demographic reasons. Three others of the top ten will be

its former colonies: the US, India and Canada.

Even today, of the IMF’s top ten countries by per capita income,

four are part of the Anglo-Saxon diaspora — the United States,

Canada, Australia and Singapore, (Hong Kong would be there too if

it were a country). Apart from Switzerland, all of the others are

small city- or petro-states: San Marino, Brunei, Qatar, Luxembourg,

Norway. It appears that we ain’t dead yet.

League tables mean little, of course, and predictions even less.

Nonetheless, there is something resilient about the “Anglosphere”

model of running a country. The recent book by Daniel Hannan MEP

— How we Invented Freedom and Why it

Matters — might have been titled to annoy foreigners, but

it contains a challenging idea. Bottom-up systems work best.

As Hannan points out, while we tend to stress the differences

between Britain and America, foreigners usually see the

similarities. The secret ingredient of the Anglosphere is not, of

course, racial. We can bury the Victorian notion that there is

something specially clever or tough about pale-skinned folk with

mostly Celtic DNA, mostly Saxon words and a mostly Protestant

faith.

Nor was it inevitable in the Whig-history sense. It was not

manifest destiny, but a chain of semi-happy accidents that gave the

English-speaking people their chance — including a sea channel to

protect against invaders, a randy king, a Dutch commercial

takeover, a coastal coalfield, a brilliant customs official from

Kirkcaldy, and a well timed tax revolt.

The secret is institutional. For Hannan, the habit of liberty

under the law proved good at generating prosperity wherever it was

adopted and whatever the skin colour of the people who caught it —

and even if it was sometimes honoured in the breach. It was a

peculiarity of the British that, early on, they got into the habit

of dispersing both property and power and never quite lost that

habit even under some strong Norman or Tudor rulers.

The monarchy was at least partly elective, the common law was

evolutionary and derived from cases rather than principles,

property was at least partly sacred, the press was fairly free,

Parliament was eventually sovereign. The Government was subject to

the law, rather than the other way round. Even in the Middle Ages

these features were visible to an unusual degree in Britain.

The common law plays a central role in Hannan’s argument — what

he calls “that beautiful, anomalous system that belongs to the

people, not the state”. Having government under the law, rather

than in charge of it, gave rise to security of property and

contract, which proved peculiarly helpful when the free market came

along and tipped the balance of incentive from predation to

production. The roots of these institutions go very deep into Saxon

times but many of the key features came together in 1688 and

1787.

For all its periodic lurches into hierarchy and imperialism, the

Anglosphere has always hemmed in its rulers with bottom-up

traditions. That is what the English Civil War and the American War

of Independence shared — two episodes in the same family argument

with surprising philosophical and religious similarities. Hannan

makes clear how much the Roundheads and the rebels both harked back

to Magna Carta and what they saw as their birthright of

liberty.

The British version of the Protestant Reformation adopted the

rejection of top-down authority, but not its usual Calvinist

substitute: providential predestination. So Protestantism became

enmeshed with freedom in that potent recipe known as Whiggery.

Besides, scholars now think the British Reformation owes as much or

more to old Lollard ideas as to new Lutheran ones. Even the English

language, unusually, never had a top-down academy to decide how it

could evolve.

The combination of free trade and some recourse against

arbitrary law did happen elsewhere, too. Phoenicia, ancient Athens,

Ashokan India, Song China, Abbasid Arabia, Renaissance Italy,

17th-century Holland — they all tried it, at least in part, with

astonishing results for their prosperity. But the experiments all

petered out because of some combination of invasion, superstition

or bureaucracy. For most of the time in most of the world, what

Hannan calls the Ming-Mogul-Ottoman habit of expecting laws to come

down from above — of uniformity, centralisation, high taxation and

state control — prevailed.

So the obvious question is whether the Anglo-Saxon experiment

with liberty under the law can last till 2028 as the CEBR report

implicitly assumes. Hannan is far from optimistic. He sees the EU

steadily undermining the common law, imposing rules and taxes

passed by appointed rather than elected commissioners, erecting

trade barriers with the rest of the world, and assuming that there

is little middle ground between regulated and compulsory.

Creeping centralisation afflicts other parts of the Anglosphere

but Hannan notes that America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and

India are busy negotiating progressively deeper free-trade

agreements among themselves. Britain, as an EU member, cannot sign

independent commercial agreements. Imagine if it could — if we

regained the power to represent ourselves at international

negotiations and aim for more access to vast, Asian markets rather

than cramped and dwindling European ones. Imagine being able to

take our own decisions about innovation — genetically modified

crops, for example. That alone would not secure our position in the

2030 league table, but it would certainly help.

December 24, 2013

The civilising process

There is a common thread running through many

recent stories: paedophilia at Caldicott prep school and in modern Rochdale, the murders of Lee Rigby in Woolwich and by Sergeant Alexander Blackman in Afghanistan, perhaps

even segregation of student audiences and

opposition to the badger cull. The link is that people are left

stranded by changing moral standards, because morality is always

evolving.

What is so striking about the prep school scandal is not only

that nobody thought at the time that a predatory headmaster was

much of an issue (just the price you have to pay, old chap, for a

really dedicated teacher), but that even ten years ago a judge

could argue that it was better for all concerned if a prosecution

was halted. The idea that the child’s welfare is paramount in such

a case is relatively new; it would have seemed laughable in the

1950s.

Compared with then, modern society is far more tolerant of

homosexuality but far less tolerant of paedophilia. The Caldicott

headmaster, Peter Wright, would probably have been prosecuted with

gusto for living openly with a man his own age in 1959, the year of

his first offence against boys.

At the time you would have been hard put to predict this moral

reversal. Indeed, some guessed wrong about how tolerance would

evolve. It has emerged that in the mid-1970s the National

Council on Civil Liberties (now Liberty) accepted the Paedophile

Information Exchange (PIE) as an affiliate member, allowed its

chairman to address its conference and passed a motion declaring

that “awareness and acceptance of the sexuality of children is an

essential part of the liberation of the young homosexual”. The Home

Office launched an investigation last week into its own apparent

funding of the PIE at the time.

Jimmy Savile just escaped, as Stuart Hall did not, this

evolution of morality. In their heyday there was not thought to be

all that much wrong in celebrities seducing under-age, star-struck

girls. The Rochdale abusers in the news last week, and those who

failed to investigate their cases thoroughly, likewise failed to

appreciate society’s changing standards.

The morality of war is changing too. Sergeant Blackman is

discovering that the modern world does not consider cold-blooded

murder, even in the heat of battle, acceptable. Such a prosecution

would never have happened after, say, Stalingrad or Normandy.

Anybody who thinks Lee Rigby’s murder would never have happened in

London in the “good old days” needs to read more history. But Anjem

Choudary and Michael Adebolajo are similarly caught out of time —

both wanting to push the moral clock back to a time when

eye-for-eye revenge against the innocent was honourable or pious.

The question responsible Muslims need to answer is why some

followers of Islam are so keen on reversing this inexorable,

progressive evolution of morality.

The best understanding of how morality evolves comes from the

work of Norbert Elias, a sociologist who had four

horrible experiences of violence: a nervous breakdown in the First

World War when fighting for Germany, emigration to escape Nazi

persecution in 1933, internment by Britain for being a German in

1940 and the death of his mother in Auschwitz. Yet half way through

this series of blows he published a book that argued the world was

getting less violent. The year 1939 was not a good year to

disseminate such a message, let alone in German. It was only when

it was translated into English in 1969, by which time Elias had

retired from Leicester University, that the book

(called The Civilising Process) shot him to

fame.

Elias had spent many hours delving into medieval archives,

concluding that life in the Middle Ages was routinely much more

violent than today. He also argued that manners and etiquette were

coarser in the old days and he linked the two. The book’s revival

was helped 12 years later by the compilation of a graph that showed

a hundredfold decrease in homicide rates per 100,000 people in

England since the 1300s: statistical evidence for Elias’s hunch.

Till then, most people thought the modern world more violent than

the old days; plenty still do.

The psychologist Steven Pinker, alerted by the graph and others

like it from all across Europe, documented in his recent

book The Better Angels of our Nature the

inexorable, widespread and continuing decline in the West in

virtually all forms of violence: homicide, rape, torture, corporal

punishment, capital punishment, war, genocide, domestic violence,

child abuse, hate crimes and more. Pinker agreed that etiquette

changes were part of the same trend.

Pinker summarises the Elias argument thus: beginning in the 11th

century and maturing in the 18th, “Europeans increasingly inhibited

their impulses, anticipated the long-term consequences of their

actions, and took other people’s thoughts and feelings into

consideration”. The root of this change lay in government and

commerce. As monarchs centralised power in feudal societies, being

polite at court began to matter more than being good at violence.

And as commerce replaced feudal obligations, people had to learn to

treat strangers as potential customers rather than potential

prey.

Whatever the explanation, there is no doubt that — with

occasional backward lurches, and some exceptions — morality has

progressed towards niceness. Hence the long list of habits that,

one by one, become unacceptable as the decades pass: hanging,

drawing and quartering; spitting at meals; slavery; cock fighting;

sexism; homophobia; smoking.

So the question immediately suggests itself. What am I doing

today that my great-grandchildren will find disgusting and might

even get me prosecuted in old age? When I asked Pinker for his

answer, he replied: “That’s easy — meat eating.” I would add field

sports. I consider hooking a trout on a dry fly, or shooting a fast

woodcock for the pot, to be acts of almost noble communion with

nature, but others already see them as barbaric. It seems unlikely

that my view will prevail in the very long run.

December 18, 2013

Medicinal regulation of vaping could kill people

My recent speech in the House of Lords on the dangers of too

much regulatory precaution over electronic cigarettes has sparked a

huge amount of interest among "vapers". I am reprinting the speech

here as a blog:

I congratulate my noble friend Lord Astor, on securing this

debate. It is an issue of much greater importance than the sparse

attendance might imply and one that is growing in importance. I

have no interest to declare in electronic cigarettes: I dislike

smoking and have never done it. I have only once tried a puff on an

e-cigarette, which did nothing for me. I am interested in this

issue as a counterproductive application of the precautionary

principle. I should say that I am indebted to Ian Gregory of

Centaurus Communications for some of the facts and figures that I

will cite shortly.

There are, at the moment, about 1 million people in this country

using electronic cigarettes, and there has been an eightfold

increase in the past year in the number of people using them to try

to quit smoking. Already, 15% of ex-smokers have tried them, and

they have overtaken nicotine patches and other approaches to

become the top method of quitting in a very short time. The

majority of those who use electronic cigarettes to try to quit

smoking say that they are successful.

Here we have a technology that is clearly saving lives on a huge

scale. If only 10% of the 1 million users in the country are

successful in quitting, that would save £7 billion, according to

the Department of Health figures given in answer to my Written

Question last month, which suggest that the health benefits of each

attempt to quit are £74,000. In that Answer, Minister said

that,

“a policy of licensing e-cigarettes would have to create very

few additional successful quit attempts for the benefits to justify

its costs”.—[Official Report, 18/11/13;

col.WA172.]

But who thinks that licensing will create extra quit attempts?

By adding to the cost of e-cigarettes, by reducing advertising and

by unglamorising them, it is far more likely that licensing will

create fewer quit attempts. Will the Minister therefore confirm

that, by the same token, a policy of licensing e-cigarettes would

have to reduce quit attempts by a very small number for that policy

to be a mistake?

Nicotine patches are also used to reduce smoking and they have

been medicinally regulated, but there has been extraordinarily

little innovation in them and low take-up over the years. Does the

Minister agree with the report by Professor Peter Hajek in

the Lancet earlier this year, which said that the

30-year failure of nicotine patches demonstrated how the expense

and delays caused by medicinal regulation can stifle innovation?

Does my noble friend also agree with analysts from Wells Fargo who

this month said that if e-cigarette innovation is stifled,

“this could dramatically slow down conversion from combustible

cigarettes”?

We should try a thought experiment. Let us divide the country in

two. In one half—let us call it east Germany for the sake of

argument—we regulate e-cigarettes as medicines, ban their use in

public places, restrict advertising, ban the sale of refillable

versions, and ban the sale of e-cigarettes stronger than 20

milligrams per millilitre. In the other half, which we will call

west Germany, we leave them as consumer products, properly

regulated as such, allow them to be advertised as glamorous, allow

them on trains and in pubs, allow the sale of refills, allow the

sale of flavoured ones, and allow stronger products. In which of

these two parts of the country would smoking fall fastest? It is

blindingly obvious that the east would see higher prices—and prices

are a serious deterrent to attempts to quit smoking because many of

the people who smoke are poorer than the average. We would see less

product innovation, slower growth of e-cigarette use and more

people going back to real cigarettes because of their inability to

get hold of the type, flavour and strength that they wanted.

Therefore, more people would quit smoking in the western half of

the country.

What are the drawbacks of such a policy? There is a risk of harm

from electronic cigarettes, as we have heard. How big is that risk?

The Minister confirmed to me in a Written Answer earlier this year

that the best evidence suggests that they are 1,000 times less

dangerous than cigarettes. The MHRA impact assessment says

that the decision on whether to regulate e-cigarettes should be

based on the harm that they do. Yet that very impact statement says

that,

“any risk is likely to be very small”,

that there is,

“an absence of empirical evidence”

and “no direct clinical evidence”, that “the picture is

unclear”, and—my favourite quote—states:

“Unfortunately, we have no evidence”,

of harm.

There is said to be a risk of children taking up e-cigarettes

and then turning to real cigarettes. Just think about that for a

second. For every child who goes from cigarettes to electronic

cigarettes, there would there have to be 1,000 going the other way,

from e-cigarettes to cigarettes, for this to do any net harm. The

evidence suggests, as my noble friend Lord Borwick has said, that

the gateway is the other way. Some 20% of 15 year-olds smoke, and

evidence from ASH and a study in Oklahoma suggests strongly that

when young people use electronic cigarettes they do so to quit,

just like adults do.

If we are to take a precautionary approach to the risks of

nicotine, will the Minister consider regulating aubergines as

medicines? They also contain nicotine. If you eat 10 grams of

aubergine, which you easily could with a plateful of moussaka, you

will absorb the same amount of nicotine as if you shared a room

with a cigarette smoker for three hours. It is not an insignificant

quantity. That is data from the New England Journal of

Medicine in 1993. If we are worried about unknown and small

risks, can the Minister explain to me why, as Professor Hajek, put

it, more dangerous chemicals, such as bleach, rely on packaging and

common sense rather than on medicinal licensing?

There has been approximately an 8% reduction in the use of

tobacco in Europe in the past year. The tobacco companies are

worried. A big part of that reduction seems to be because of the

rapid take-up of electronic cigarettes. They are facing their Kodak

moment—the moment when their whole technology is replaced by a

rival technology that, in this case, is 1,000 times safer. Does my

noble friend think that there may be a connection between the rise

of electronic cigarettes, the rapid decline in tobacco sales and

the enthusiasm of tobacco companies for the medicinal regulation of

electronic cigarettes?

It is not just big tobacco; big pharma has shown significant

interest in the regulation of electronic cigarettes. That is not

surprising because they are, again, a rival to patch products and

other nicotine replacement therapies. Perhaps more surprising is

that much of the medical establishment is in favour of medicinal

regulation. I never thought I would live to see the BMA and the

tobacco industry on the same side of an argument. The BMA says that

electronic cigarettes cannot be considered a lower-risk option, but

this completely flies in the face of the evidence. As we have heard

already, electronic cigarettes are 1,000 times safer. The BMA says

that it is worried about passive vaping, the renormalising of

smoking and the use of electronic cigarettes as a gateway to

smoking. The excellent charity Sense About Science, to which I

am proud to be an adviser, has asked the BMA for evidence to

support those assertions. I must say that there is a strong

suspicion that the only reason the medical establishment wants to

see these things regulated as medicines is because it cannot bear

to see the commercial sector achieving more in a year in terms of

getting people off cigarettes than the public sector has achieved

in 10. Instead of talking about regulating this product, should we

not be talking about encouraging it, promoting it and letting

people vape indoors if they want to—in pubs, on trains and in

football grounds—specifically so that they are tempted to vape

instead of smoke? That would be of enormous benefit to them and to

the country as a whole.

I end by asking specifically in relation to the agreement that,

as we heard from my noble friend Lord Borwick, was agreed last

night, what its impact will be on what is happening, and in

particular on advertising. As I understand it, under the agreement

reached yesterday, it will be possible for the advertising of these

things to be banned as if they were cigarettes. What is the

justification for that, given the proportionality and the evidence

that they will actually save lives rather than harm them?

Here are some of the messages I have received since making the

speech:

I would like to show my sincere gratitude to you for the honest

facts on the debate in the House of Lords regarding e-cigarettes

... I was a 30+ a day cigarette smoker for nearly 50 years and have

not had a single one since I found the e-cig 11 months ago, my

health has vastly improved .... thank you!

I'll lift my hat for your effort to explain, how vapers would

have been affected by eu regulations. Started to smoke at age

9, tried every thing to stop in the next 50 years (

nicorette-hypnosis akupunktur, you name it ) In juli i

bought my first e-cigarett, with 12mg/ml nicotine :) for the

first time in 50 years I was not smoking but vaping, and are

now after 5 months down to 6mg nicotine.

Thank you for your support in our fight to give every smoker the

chance to move away from the lit tobacco that is killing them. I

hope you enjoyed being able to make all the statements from a

position of science and common sense, not fettered by the big

tobacco and pharma companies. I speak as an ex smoker who is

now a vaper with no attachment to the e cig business. Can I

leave you with one thought. I know, over Internet, thousands of

vapers and most of the long term ones reduce their nicotine. I have

reduced mine from 24mg to 6mg in nine months. What other form of

addiction has "users" REDUCING their substance of addiction.

Nicotine may not be "highly addictive" as commonly quoted.

From across the pond we are making your speech viral amongst the

fold of E-Cigarette users and yes you are right in every word.

I have quit smoking thanks to E-Cigarettes like so many

British and Europeans have. I am so proud of not smoking

anymore after 40 yrs. of smoking, and I am hoping that the TRUTH

that you spoke of will spread and grow eventually that it will out

way the greed from the opposition. Thank you from the bottom

of my heart for your bravery and brilliance.

I would like to thank you for your outstanding speech on

E-Cigarettes on 17 Dec 2013 (seen on CASAA link), I have to

applaud your sensible argument in support of E-Cigs based on

science and common sense. The rubbish that has been propagandized

by the anti-smoking, Big Tobacco companies and Big Pharma

groups has been obscene, especially when E-Cigs can save thousands

of lives. I smoked for 40 years and have now stopped for over 7

months by using an E-cig which I have lowered my nicotine levels

down to 9mg during this time. I know that thousands of people are

doing the same thing as I am.

And finally...!

I would just like to express my appreciation for the speech to

the Lords regarding Electronic Cigarettes. I was thinking I'd have

to vote UKIP next time.

Is there life on Europa?

My Times column on how earthlings communicate

with life in space:

The Hubble telescope has revealed that Europa, a

moon of Jupiter, has fountains of water vapour near one of its

poles, which means its ocean might not always be hermetically

sealed by miles-thick ice, as previously assumed.

Europa’s huge ocean, being probably liquid beneath the ice, has

long been the place in space thought most favourable to life, so

the prospect of sampling this Jovian pond for bugs comes a little

closer. My concern is a touch more mundane. Who’s in charge of

the response down here when we do find life in space?

Even if we only find a blob of protoplasmic ooze, the arguments

could get wild. Who is allowed to study it? Who sets the rules

about not polluting or harming it? And if instead we receive a

radio signal from intelligent life — and such a broadcast might

arrive any day — imagine the chaos. President Obama will make a

soaring but content-free speech, while his generals will act as if

the matter is entirely for them; Ban Ki Moon will set up a

committee with gold-plated expense accounts; Vladimir Putin will

send a reply unilaterally; the Chinese (who released a rover on the

Moon this weekend) will hack the aliens’ computers; Lady Ashton of

the European Union will issue directives.

And that’s just the governments. Before the news is cold, Green

lobbyists will have demanded — and been granted — observer status

at any meetings being held to decide what happens, will have

persuaded European commissioners to divert funds their way to lobby

them on the matter (this circular feedback is known as

sock puppetry) and will have announced they are to sue

governments for not taking the life forms’ interests into

sufficient account when launching communication satellites.

Meanwhile, a shady group of the Green Great and Good — those

rich people who like telling others to live more frugally — will

meet in a luxury resort to draw up ethical guidelines for the rest

of the world to follow when dealing with extraterrestrials. The

guidelines will surprisingly include the suggestion of

well-salaried jobs for themselves.

The International Academy of Astronautics drew up a protocol in 1996 for

deciding whether and how to reply to a radio signal from aliens.

It’s fairly vague, but it does suggest that “the United Nations

General Assembly should consider making the decision on whether or

not to send a message to extraterrestrial intelligence, and on what

the content of that message should be, based on recommendations

from the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space of the

United Nations and within other governmental and non-governmental

organisations”.

Somehow that prospect horrifies me. Who would be on the

committee set up by the UN to write the reply? The Pope probably; a

chap from the Pentagon perhaps; an ex-Norwegian prime minister

almost certainly; the head of the World Wildlife Fund; and of

course Bono. The mind boggles.

In the movies it’s all so much simpler. Scientist (Jeff Goldblum

or Sigourney Weaver) goes and tells president (Tommy Lee Jones or

Morgan Freeman) he’s made contact, then hero (Will Smith or Bruce

Willis) does the necessary violence. There’s neither need nor time

for summits, protocols, plebiscites and arguments over money. In

real life, things would very quickly get a lot more bureaucratic, a

lot more bad-tempered and a lot less exciting.

Within days of first contact with alien life, the news coverage

would become deadly dull and all too earthly. You can almost write

the BBC News report now: “The Prime Minister today defended his

decision to fund the UK’s 2 per cent stake in the mission to

communicate with extraterrestrial life forms by cutting language

courses for Bulgarian immigrants. Protests at the awarding of the

contract to a private security firm are planned for later today.”

That sort of thing.

Another alarming thought: the place is called Europa. What

adjective are we to use for the creatures: Europans? Spellchecker

nightmare. Then imagine the preening that will go on in Brussels,

and the gnashing of teeth at Tory headquarters. Is it not just our

bad luck that the most promising body in the entire solar system

for alien life should turn out to have the same name as that bane

of our existence, that byword for boringness, Europe?

I mean, why could a frozen ocean not have turned up on Callisto,

Io or Ganymede? Or Hegemone, Sinope, Callirrhoe or Eukelade?

(Jupiter’s big moons are named after Zeus’s conquests, small ones

mostly after his offspring and would-be conquests.) Actually,

there’s a glimmer of hope: in 2005 the spacecraft Cassini found

good evidence of water plumes near the south pole of Enceladus, a

small but hospitable-looking moon of Saturn that also seems to have

a frozen ocean. Do let’s check that one out first.

Last year I was lucky enough to meet the man who is putting

together for Nasa some of the technology for exploring the ocean on

Europa. A ridiculously capable Texan named Bill Stone, he dives in

very deep caves in Mexico, travelling underground for weeks on end;

he also designs highly sophisticated autonomous

robots, and he thinks deeply about space exploration. One of

his probes has successfully solved a key problem already. Unleashed

beneath the four-metres-thick ice of an Antarctic lake, it went off

exploring on its own, then came back, homing precisely on the hole

in the ice where its journey started.

That combination of autonomy and homing skill will be necessary

on Europa, where radio messages from Earth would take half an hour

to arrive and would probably never penetrate the ice. Now it’s just

a matter of getting Bill Stone’s probe on to the surface of Europa,

and working out how it will melt its way down through miles of ice

and back again.

All very simple really, at least compared with solving the

politics of deciding what to do about alien life forms.

December 15, 2013

Heritable IQ is a sign of social mobility

My fellow Times writer the

cricketer Ed Smith posed me a very good question the other day. How

many of the people born in the world in 1756 could have become

Mozart? (My answer, by the way, was four.) So here’s a similar

question: how many Britons born in 1964, if educated at Eton and

Balliol, could have achieved what Boris Johnson has achieved? It’s

clearly not all of them; it’s probably not one; but it’s not a big

number.

My point? There is little doubt that Boris Johnson is a highly

intelligent man, notwithstanding his inability to cope with a radio

ambush of IQ test questions, and that he would be a highly

intelligent man even if he had not gone to Eton and Balliol —

barring extreme deprivation or injury.

The recent burst of interest in IQ, sparked first by Dominic

Cummings (Michael Gove’s adviser), and then by Boris, has been

encouraging in one sense. As Robert Plomin, probably the world’s

leading expert on the genetics of intelligence, put it to me, there

used to be a kneejerk reaction along the lines of “you can’t

measure intelligence”, or “it couldn’t possibly be genetic”. This

time the tone is more like: “Of course, there is some genetic

influence on intelligence but . . .”

The evidence from twin studies, adoption studies and even from DNA evidence is relentlessly consistent: in children, in

Western society, the heritability of IQ scores is about 50 per

cent. The other half comes equally from family (shared environment)

and from unshared individual experiences: luck, teachers,

friends.

This numerical precision easily misleads us into thinking genes

and environment struggle against each other. In fact, they are like

two pillars supporting an arch: nature makes you seek out nurture,

which brings out your nature. But here is where things get

interesting. The acceptance of genetic influence on intelligence

leads to some surprising, even paradoxical implications, some of

which turn the assumptions of both the Right and the Left upside

down.

First, if intelligence was not substantially genetic, there

would be no point in widening access to universities, or in grammar

schools and bursaries at private schools trying to seek out those

from modest backgrounds who have more to offer. If nurture were

everything, kids unlucky enough to have been to poor schools would

have irredeemably poor minds, which is nonsense. The bitter irony

of the nature-nurture wars of the 20th century was that a world

where nurture was everything would be horribly more cruel than one

where nature allowed people to escape their disadvantages.

The Left, which has championed nurture against nature, is

learning to take a different view — over homosexuality, for

example, or learning disability, genetic influence is used as an

argument for tolerance. A recent Guardian headline

criticised Boris by saying “gifted children are failed by the

system”, which presupposes the existence of (genetically) gifted

children.

The second surprise is that genetic influence increases with age. If you measure the

correlation between the IQs of identical twins and compare it with

that of adopted siblings, you find the difference grows

dramatically as they get older. This is chiefly because families shape the

environments of young children, whereas older children and adults

select and evoke environments that suit their innate preferences,

reinforcing nature.

[See the new paper by Briley, D. A. , &

Tucker-Drob, E. M. (in press). Explaining the

increasing heritability of cognitive ability over development: A

meta-analysis of longitudinal twin and adoption studies.

Psychological Science.]

It follows — the third surprise — that much of what we call the

“environment” proves to be itself under genetic influence. Children

who are very good at reading are likely to have parents who read a

lot, schools that give them special opportunities and friends who

recommend books. They create a reading-friendly environment for

themselves. The well-documented association between family

socio-economic status and IQ, routinely interpreted as an

environmental effect, is, writes Professor Plomin and colleagues,

“substantially mediated by genetic factors”. Perhaps intelligence is an appetite, at least much as

an aptitude, for learning.

The fourth surprise is that the better the economy, education,

and welfare are, the more heritable IQ will be. Just as having

extra food will make you brighter if you are starving, but not if

you are plump, so the same applies to toys, teachers, books and

friends. Once you have enough of any of these things, having more

will not make as much difference. So differences due to environment

will fade. In a world when some are starving and some are kings,

the differences would be mainly environmental. In a world where all

went to Balliol, the main difference remaining would be genetic.

Social reformers rarely face this fact — the more we equalise

opportunity, the more the people who get to the top will be the

genetically talented.

And this brings a final paradox: a world with perfect social

mobility would show very high heritability. The children of Balliol

parents would qualify for Balliol disproportionately, having

inherited both aptitude and an appetite for evoking the

environments that amplified that aptitude. Far from indicating that

parents are giving their children unfair environmental advantages,

a high correlation between the achievements of parents and

offspring suggests that opportunity is being levelled, albeit

slowly and patchily. In Professor Plomin’s words: “Heritability can

be viewed as an index of meritocratic social mobility.”

Moreover, assortative mating is probably reinforcing the trend.

That is to say, 50 years ago, when women were not often allowed

near higher education, Professor Branestawm chose to marry the girl

next door because she was good at ironing his shirts, whereas today

he marries another professor because she writes gorgeous equations

about quantum mechanics, and they have children who are professors

squared.

We are a long way from equality of opportunity, but when we get

there we will not find equality of outcome. Already IQ — for all

its flaws as an objective measure of intelligence — is good at

predicting not just educational attainment, but income, health and

even longevity remarkably well.

Do we reconcile ourselves to inequality, then? No! Just because

capability is inherited does not mean it is immutable. Hair colour

and short sight are highly heritable , but both can be altered.

Education is not just about coaxing native wit from the gifted, but

also coaching it into the less gifted.

December 6, 2013

Gas and oil prices may soon fall

My Times column was on the likely effect of weaker

oil and gas prices on competitiveness:

The Chancellor is to knock £50 off the average

energy bill by replacing some green levies with general taxation

and extending the timescale for rolling out others. On the face of

it, the possibility that global energy prices may start to fall

over the next few years might seem like good political news for

him, and some of the chicken entrails do seem to be pointing in

that direction. There is, however, a political danger to George

Osborne in such trends .

For Government strategists reeling from the twin blows of Ed

Miliband’s economically illiterate but politically astute promise

of an energy bill freeze and the energy companies’ price hikes, the

prospect of lower wholesale energy prices might seem heaven sent.

But in many ways it only exacerbates their problems, for the

Government is right now fixing the prices we will have to pay for

nuclear, wind and biomass power for decades to come. And it is

fixing those prices at quite a high level.

The more that oil, gas and coal prices drop, the worse these

deals look and the more they threaten our economic competitiveness.

The Liberal Democrats have not allowed the Chancellor to cut

subsidies for the renewable energy industry, the most regressive

redistribution of wealth since the Sheriff of Nottingham was in his

pomp.

They argue that what has driven energy bills up threefold in ten

years is mainly an increase in the wholesale price of energy,

rather than any great lurch towards subsidising renewables. True,

but most of the lurch is yet to come and as wind power capacity

quadruples by 2020, it will add £400 to average bills — not to

mention driving up the price of energy to industry, which will pass

it on to consumers.

“There is not a low-cost energy future out there,” said Ed Miliband when Secretary of State for

Energy and Climate Change in 2009, at the time an enthusiast for

discouraging energy use by price rises. It even became fashionable

to argue, when Chris Huhne filled that post, that

higher prices would cut bills (yes, you read that right) by

encouraging people to use less power.

Anyhow, the forces that have driven energy prices up in recent

years appear to be fading. Consider some of the reasons that oil

and gas prices rose in 2011, the year energy companies pushed up

prices even more than this year. Japan suffered a terrible tsunami,

shut down its nuclear industry and began scouring the world for gas

imports to keep its lights on. At about the same time Libya was

plunged into civil war, cutting off a key supplier of gas. Add in

simmering tension over Iran, Germany’s sudden decision to turn its

back on nuclear power, the legacy of a couple of cold winters and

the lingering depressive effect on oil and gas exploration of low

energy prices from much of the previous decade, and it is little

surprise that oil and gas producers pushed up prices.

Contrast that with today. Several years of high prices have

driven a surge of new exploration. Deep offshore technology is

advancing rapidly and huge gas fields have been found in the

Mediterranean and in the Indian and Atlantic oceans. In the United

States, the shale revolution has glutted both gas and oil markets,

displacing imports. Iran is coming in from the cold, Libya is back

on stream and Australia is preparing to export huge volumes of gas.

Should the rest of the world start producing shale gas — China,

Argentina, Poland and others are on the brink, even Britain might

one day deign to join them — that would further add to supply.

A decade is a long time in energy policy. Ten years ago, no less

an oracle than Alan Greenspan told Congress: “Today’s tight natural

gas markets have been a long time in coming, and distant futures

prices suggest that we are not apt to return to earlier periods of

relative abundance and low prices anytime soon.” Abundance and low

prices are exactly what America now has: so much so that it is

using gas instead of coal to provide base-load electricity,

investing heavily in manufacturing and chemical industry, and

shifting some of its road transport from oil to gas. By 2020, shale

gas will have boosted the American economy by £500 billion, 3 per

cent of GDP and 1.7 million jobs, according to McKinsey Global Institute.

Meanwhile, the argument that the running out of fossil fuels is

what has been driving up prices has been proven once again, for the

third time in my lifetime, to be bunk. America, the most explored

and depleted oil and gas field in the world, is now increasing its

oil and gas production at such a rate of knots that it is heading

towards self-sufficiency. If an oil field as gigantic as the Eagle

Ford can be found (through technological innovation) in Texas,

think how much awaits explorers in the rest of the world. Even five

years ago, gas was thought likely to be the first of the fossil

fuels to run out. Nobody thinks that now.

At least nobody outside Whitehall. As Professor Dieter Helm told a House of Lords committee last month: “I

think one should be very sceptical about this Government and the

last Government embarking on policies that require them to assume

that the oil and gas prices are going to go up and then pursuing

those policies and not being willing to contemplate the consequence

of that not being the case.” According to Peter Atherton of Liberum

Capital, the recent “strike price” deal with EDF to build a nuclear

power station at Hinckley Point in Somerset will only look good

value to consumers if gas prices more than double by 2023.

Suppose, instead, world energy prices come down, even as the

cost of subsidising renewables and nuclear starts to bite. We will

have rising energy bills while the rest of the world has falling

ones. That is a recipe for job destruction.

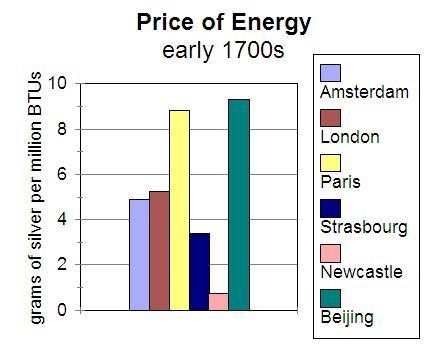

One of my favourite charts – I know, I should get out more – comes from Professor Robert Allen of the

University of Oxford. It shows the cost of energy, as measured in

grammes of silver per million BTUs, in various world cities in the

early 1700s. Newcastle stands out like a sore thumb, with energy

costs much lower than London and Amsterdam, and far lower than

Paris and Beijing. The average Chinese paid roughly 20 times more

for heat than the average Geordie. This meant that turning heat

into work (via steam engines) throughout the north of England was

profitable. In China, by contrast, it made more sense to employ

lots of people, on low wages . The result was an industrial

revolution in Britain with innovation and rising living standards

and an “industrious” revolution in China (and Japan) with falling

living standards.

Affordable energy is the indispensable lifeblood of economic

growth. Back in 2011, David Cameron was warned by an adviser that electricity, gas

and petrol prices were of much greater concern to voters than any

other issue, including the NHS, unemployment, public sector cuts

and crime. If subsidies for windmills prevent us from passing on

any future falls in gas and oil prices, and jobs flee to lower-cost

countries, the voters will not be forgiving.

December 2, 2013

Immigration versus social cohesion?

My Times column is on immigration:

It looks as if David Cameron is determined not to

emulate Tony Blair over European immigration. Faced with opinion

polls showing that tightening immigration is top of the list of

concerns that voters want the Prime Minister to negotiate with

Europe, he is going to fight to keep a Romanian and Bulgarian

influx out as Mr Blair did not for Poles in 2004. It is the ideal

ground for him to pick a fight with Brussels.

One reason is that he now has more political cover on the issue

of immigration. It is no longer nearly as “right wing” an issue as

it once was, though popular enough with UKIP voters. Migration as a

political issue seems itself to be migrating across the political

spectrum from right to centre, if not left. Where once any kind of

opposition to immigration was seen by left-wing parties and the BBC

as just a proxy for racism, increasingly it is now a subject for

real debate.

The best example of this is the positive reception that Paul

Collier’s new book Exodus has received from the bien-pensant

Left. Collier has raised worries about immigration with which

left-leaning commentators can sympathise: in particular social

cohesion and the effect on the global poor. He is following a path

pioneered by David Goodhart, whose book The British Dream argued that overzealous

multiculturalism had “reinforced difference instead of promoting a

common life”, putting at risk the welfare state.

Both books make the case that the generosity with which British

citizens are prepared to hand welfare payments to others could be

damaged if Britons no longer think of their neighbours as part of

the same “country”. In effect they are voicing an old-fashioned

nationalism. Collier warns that “while migration does not make

nations obsolete, the acceleration of migration in conjunction with

a policy of multiculturalism might potentially threaten their

viability”. Nations, he points out, have fallen out of favour as

“solutions to collective action problems”. It is not clear how

large an unabsorbed diaspora could get before it weakened “the

mutual regard on which society depends”.

Of course, the diaspora that the British migrants established

around the world, swamping native Americans, Aborigines, Maoris and

French Canadians, created a rather successful sense of

supranational solidarity. Daniel Hannan’s new book How We Invented Freedom and Why it Matters,

published today, tells an extraordinary story about how the values

of “the West” were actually a very peculiar set of Anglosphere

traditions — above all, the notion that the State is the servant,

not the master, of the individual.

He argues that this idea, carried by emigrants from one damp

island to North America and Australasia, is quite distinct from the

top-down traditions of many other European countries. Freedom

survived the mid 20th century by the skin of its teeth, thanks

almost entirely to the Anglosphere. When Boris Johnson says that

the current system of immigration is mad, “cracking down on

Australians and New Zealanders and high-spending Chinese students

and tourists — but completely incapable of dealing with a sizeable

influx from within the EU, some of whom show no sign of wanting to

work”, he is partly echoing the idea that we feel solidarity with

the Anglosphere but not the Eurosphere.

In a thought-provoking article for Wired magazine this month, Balaji

Srinavasan, a Californian entrepreneur and academic, argues that

many people now feel social solidarity with virtual diasporas,

“finding their true peers in the cloud, a remedy for the isolation

imposed by the anonymous apartment complex or the remote rural

location”. He then makes the startling claim that such virtual

diasporas may be about to become real ones, as such people get

drawn together to found some colony of like-minded folk, either

within a country or maybe offshore or on Mars.

That’s a long way off. But it is a reminder that the migration

argument in support of international solidarity is beginning to

sound more like a right-wing one. Libertarian-leaning economists on

the right continue to sing the praises of migration, arguing that

free trade in people is just as valuable as free trade in goods and

services. And the Right’s traditional supporters, the wealthy, are

indeed the main beneficiaries of immigration in the form of

nannies, cleaners, waiters and oncologists.

Perhaps as racial prejudice fades — and the number of white

people who even secretly dislike non-white people merely because

they are non-white must surely be falling with almost every funeral

— a great realignment will become apparent, with migration being

seen increasingly through the lens of what it does to what used to

be called the working class: competition for low-wage jobs, houses,

threats to their culture.

In short, Mr Cameron is right to pick a fight on the length of

time an immigrant must stay before claiming welfare. It plays into

the social cohesion point beloved of the Centre Left. When Collier

says that “it may prove unsustainable to combine rapid migration

with multicultural policies that keep absorption rates low and

welfare systems that are generous”, he’s only rephrasing in

academic lingo what plenty of ordinary people think.

The unprecedented wave of immigration that Britain received

between 1997 and 2010 (about 3.2 million net immigrants) did not

just put pressure on housing and welfare; it also put pressure on

culture. The more that immigrants fail to integrate, either by

sheer numbers or by the encouragement of multiculturalism, the more

resented they will be. What America did so well for so long was to

suck in millions of people from Ireland, Germany, Italy and Africa

but turn them into flag-waving democrats who loved free

enterprise.

As the history of America showed, migration has a tendency to

accelerate because diasporas tend to draw more people after them.

Collier adds that rising incomes in poor countries lead to still

more acceleration, not less, since the very poorest cannot afford

the price of a people-smuggler’s fee, let alone an air fare. The

slave trade excepted, the people who flocked to the United States

were not the poorest of the global poor from rural parts of Asia

and Africa. They were the moderately poor urban masses of Europe.

Likewise, today it is generally the people who have already

migrated from village to city, and scraped together some savings

who come to Britain. Even rising educational standards accelerate

migration by allowing more people to surmount any educational

hurdles in the path of migrants, Collier argues.

So there’s no prospect of immigration pressure easing even

though poor countries are getting rich faster than we are. It’s

obvious that this country cannot have unrestrained migration, and

equally obvious that it cannot have no migration. The question is,

and always will be, how much.

Put Collier’s and Hannan’s books together and you get one clear

recommendation. A country like Britain should do its utmost to pull

in as many talented people from poor countries as it can, turn them

into fans of the Anglosphere tradition of freedom, and send them

back home where they can help enrich and liberate the poor, while

not threatening the livelihoods of poorer people here. In short,

stop making life difficult for foreign students.

November 28, 2013

Spectator Australia diary

After my recent visit to Australia I wrote the diary column in the Australian edition of the

Spectator:

I flew from London into Sydney, then Melbourne, to make three

dinner speeches in a row. Through nerves I never finished the main

course of three dinners. Pity, because in my experience Australian

food is as fine as anywhere in the world: fresher than American,

more orientally influenced than France and more imaginative than

Britain. That was certainly not true the first time I visited

Australia 37 years ago, when I slept in youth hostels and Ansett

Pioneer buses, and ate rib-eye steaks for breakfast. I still

remember with horror the moment I realized I had left my wallet on

a park bench in Alice Springs, dazed after 31 hours on a bus. I

went back and it was still there, wet from a lawn sprinkler.

Like Britain, Australia’s been confronting the costs of climate

policies. The Abbott government has begun to deal with them

robustly, whereas in Britain we are still in denial. Our opposition

leader Ed Miliband has promised to “freeze” energy bills for two

years if he gets into power – a threat that probably caused

companies to push them up now -- even though it was he as Energy

and Climate Change secretary who did most to load green levies on

to consumers. Conservatively it looks like his Climate Act of 2008,

with its targets for carbon emission cuts, will cost us £300

billion by 2030 in subsidies to renewable energy, in the cost of

connecting wind farms to the grid, in VAT, in costs of insulation

and new domestic appliances, and in the effect of all this on

prices of goods in the shops. If people are upset about the cost of

energy now, they will be furious by the election in 2015. I don’t

like to say “I told you so”, but I did, in my maiden speech in the

House of Lords in May: “One reason why we in this country are

falling behind the growth of the rest of the world is that in

recent years we have had a policy of deliberately driving up the

price of energy.” David Cameron should take note that Tony Abbott

is the first world leader elected by a landslide after expressing

open skepticism about the exaggerated claims of imminent and

dangerous climate change. Nor can greens argue that the issue was

peripheral. The carbon tax was what won Mr Abbott his party’s

leadership, and it was front and central in the election campaign.

More and more politicians will be finding out that defending green

levies on energy bills is more of an electoral liability than

doubting dangerous climate change.

One of the more incoherent arguments for green energy policies,

repeated unthinkingly by Mr Cameron recently, is that they are an

“insurance policy” against future typhoons like the one that

devastated the Philippines. Since there has been no increase in

either frequency or intensity of tropical cyclones during the

period of global warming since 1980 – if anything the reverse – and

since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change thinks “the

global frequency of occurrence of

tropical cyclones will either

decrease or remain essentially unchanged”, this makes no sense.

There are going to be typhoons in the Pacific whether it warms or

not. What sort of insurance policy is it that costs you a fortune,

does nothing to reduce the risk and does not pay out? The way to

save lives from typhoons is to equip people with better shelter,

communications, transport and rescue services – in short to make

them richer. That’s what we have been doing, thanks to fossil

fuels, which is why global death rates from storms are down by 55%

since the 1970s.

Another issue that has parallels in Britain and Australia is

freedom of speech. Julia Gillard’s government tried in its dying

days to use the excuse of the phone hacking scandal in Britain

bring in a clumsy form of press censorship. Did embarrassing

revelations about a union slush fund have anything to do with it?

Says Hedley Thomas of The Australian: “we may never know for

certain, but the attempted regulation reeked of payback.” Thanks

partly to a vigorous campaign by the Institute of Public Affairs, a

free-market think-tank in Melbourne, she failed.

Payback is exactly how most British parliamentarians apparently

see the issue of press regulation. Almost every MP and lord seems

to have a sore memory of being viciously and inaccurately traduced

by a British newspaper (I know I do: the Guardian regularly

publishes hilariously nasty and misleading pieces about me). There

is no doubt that if they could, politicians would use the threat of

the expensive arbitration proposed by a new Royal Charter to

intimidate journalists into self-censorship. It’s a very dangerous

mood. Even lip service to freedom of the press is in pretty short

supply in the House of Lords.

Hyde Park in Sydney is full of white ibises – though many are a

dirty grey. Big birds with bare black heads and ludicrously long,

curved beaks, they scavenge litter. A colony of them nesting in a

palm tree made jabberwocky squawks as I walked beneath. This is

new: white ibises colonized the city in the last two decades. It is

a worldwide phenomenon – local wildlife becoming urbanized. Time

was, only rats, sparrows, starlings and rock doves (town pigeons)

lived in city centres. Increasingly, these face competition from

more species that used to be too shy to come near human beings.

London is now full of wood pigeons, not to mention foxes, sparrow

hawks, ring-necked parakeets (from India) and even peregrine

falcons. Because urban human beings – unlike rural ones – never

kill wildlife, urban life is safer and more reliable.

November 25, 2013

The Frackers

My review of Gregory Zuckerman's book The Frackers appeared in The Times on 23

November.

In the long tradition of serendipitous mistakes that led to

great discoveries, we can now add a key moment in 1997. Nick

Steinsberger, an engineer with Mitchell Energy, was supervising the

hydraulic fracturing of a gas well near Fort Worth, Texas, when he

noticed that the gel and chemicals in the “fracking fluid” were not

mixing properly. So the stuff being pumped underground to crack the

rock was too watery, not as gel-like as it should be.

Steinsberger noticed something else, though. Despite the mistake

in mixing the fracking fluid, the well was producing a respectable

amount of gas. Over a beer at a baseball game a few weeks later he

mentioned it to a friend from a rival company who said they had had

good results with watery fracks elsewhere. Steinsberger attempted

to persuade his bosses to try removing nearly all the chemicals

from the fluid and using mostly water. They thought he was mad