Matt Ridley's Blog, page 38

August 24, 2014

Try free enterprise in Europe

My recent Times column was on the stagnation of European

economic growth rates:

The financial crisis was supposed to have

discredited the “Anglo-Saxon” model of economic management as

surely as the fall of the Berlin wall discredited communism. Yet

last week’s numbers on economic growth show emphatically the

opposite. The British economy is up 3.2 per cent in a year, having

generated an astonishing 820,000 jobs. We are behaving more like

Canada, Australia and America than Europe.

If you think one year is too short, consider that (as David Smith pointed out in the Sunday Times)

Britain’s GDP is now 30 per cent higher than it was in 1999,

whereas Germany, France and Italy are just 18 per cent, 17 per cent

and 3 per cent more prosperous respectively. For all Britain’s huge

debt burden, high taxes and chronic problems, we do still seem to

be able to grow the economy. Thank heavens we stayed out of the

euro.

The performance of the euro economies continues to be dismal. Last week’s news was that France is flatlining,

Germany shrinking slightly and Italy back in recession for its

third dip. Spanish unemployment is just a tad under 25 per cent.

The Greek economy continues to contract; even the Dutch economy is

bumping in and out of growth. The eurozone as

a whole is flat and teeters on the brink of debilitating

deflation. This at a time when the world economy, driven by Asia

and Africa, is roaring ahead at a forecast 3.7 per cent this year,

according to the International Monetary Fund.

The euro is not primarily to blame for eurosclerosis; there has

been plenty wrong with domestic policies in the individual

countries, though joining the euro allowed them to conceal their

mistakes for a while. But all the lessons point in the same

direction: public spending and dirigisme to stimulate growth does

not work, while limiting taxes and regulation to unleash growth

does.

Patrick Minford and Jiang Wang produced clear evidence a few years ago that “the

surest way to increase economic growth is to reduce government

spending and taxation”: as figures from the Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development confirm, a 10 per cent

increase in public spending produces a 0.5-1 per cent decrease in

growth rates. The encouragement of free enterprise is what has

always brought growth, from ancient Phoenicia to modern Mauritius,

from Renaissance Italy to Silicon Valley.

Poland’s economy has doubled in size since the fall of

communism, while Ukraine’s has stagnated, because Poland made a far

more urgent dash in the direction of free markets in labour,

capital and trade. Estonia has been the top performing of the

former Soviet colonies because Mart Laar, the historian who became

prime minister in 1992 at the age of 32, had read only one book on

economics, Milton Friedman’s Free to Choose and

was in his own words “so ignorant” that he thought

flat taxes, privatisation and the abolition of tariffs and

subsidies constituted normal policy in the West.

Mr Laar ignored the warnings from most Estonian economists, who

told him what he proposed was as “impossible as walking on water”.

There’s a common theme here. Germany’s postwar economic miracle

happened because Ludwig Erhard abolished rationing and freed up

markets in the teeth of expert advice. When the American general

Lucius Clay said his experts thought these policies were a bad

idea, Erhard replied “so do mine”, and did it anyway. When Sir John

Cowperthwaite turned Hong Kong into a low-tax, free-trade enclave

in the 1960s, he had to turn a blind eye to the instructions of his

LSE-educated masters in London. Indeed, he kept failing to send

them data so they could not see what was happening.

A recent analysis by three German economists for

the think-tank Politeia looked at the reasons for the economic

transformations of Ireland (from 1986), Sweden (1991), New Zealand

(1988), Chile (1974) and Brazil (1990), all of which resulted in

sustained bursts of rapid economic growth after long spells of

stagnation, and concluded that the causes in every case were

deregulation of goods and services markets, liberalisation of

labour markets, abolition of tariffs or subsidies, privatisation of

state enterprises and the encouragement of competition.

“Anglo-Saxon” stuff in every case.

Sweden is an interesting case, because many people still think

of it as showing an alternative route to prosperity than the

Anglo-Saxon one. Nima Sanandaji, a Kurdish-Swede, demonstrated the very opposite in a paper for

the Institute for Economic Affairs two years ago. He concluded:

“Sweden did not become wealthy through social democracy, big

government and a large welfare state. It developed economically by

adopting free-market policies in the late 19th century and early

20th century.”

Between 1870 and 1936, when it was a poster boy for Adam Smith,

Sweden had the fastest growth rate in the industrialised world and

spawned Volvo, Ikea, Ericsson, Tetra Pak and Alfa Laval. Then

between 1950 and 1990 it went from having an unusually small state

sector to having a very big one. The result was currency

devaluation, stagnation and slow growth, culminating in a

full-blown economic crisis in 1992 and a rapid fall down the

economic league tables. When it then cut taxes, privatised

education and liberalised private healthcare in the 1990s, it

rediscovered growth and sailed through the financial crisis in

pretty good shape.

Entire continents teach the same lesson. South America and now

Africa have both confirmed the hypothesis that state-directed

commerce leads to stagnation while free enterprise causes rapid

growth.

As the economic historian Deirdre McCloskey argues in her forthcoming

book Bourgeois Equality, the chief beneficiaries

of free enterprise revolutions are the poor. As a result of what

she calls “the great enrichment” since 1800, she says “millions

more have gas heating, cars, smallpox vaccinations, indoor

plumbing, cheap travel, rights for women, lower child mortality,

adequate nutrition, taller bodies, doubled life expectancy,

schooling for their kids, newspapers, a vote, a shot at university

and respect. Never had anything similar happened, not in the glory

of Greece or the grandeur of Rome, not in ancient Egypt or medieval

China.”

When Mahatma Gandhi was asked what he thought about western

civilisation, he said it would be a good idea. Likewise,

continental Europe’s approach to free enterprise should be to “give

it a try”. How many more years of self-imposed depression must the

European continent suffer before its political masters get over

their ideological prejudices against Anglo-Saxons and try reading a

little Adam Smith, Friedrich Hayek or Milton Friedman?

August 15, 2014

Reasons to be cheerful

The Times carried my article arguing that things are still going

well for the world as a whole even in a month of war, terror and

disease. I have illustrated it with two superb charts from ourworldindata.org, a website being developed

by the talented Max Roser.

Is this the most ghastly silly season ever? August 2014 has

brought rich pickings for doom-mongers. From Gaza to Liberia, from

Donetsk to Sinjar, the four horsemen of the Apocalypse — conquest,

war, famine and death — are thundering across the planet, leaving

havoc in their wake. And (to paraphrase Henry V), at their heels,

leashed in like hounds, debt, despair and hatred crouch for

employment. Is there any hope for humankind?

Consider the litany of horror that faces the world. A religious

war between militant Islam and its enemies is flaring all across

Eurasia, from Pakistan through Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Libya,

Somalia, South Sudan to Nigeria. In Ukraine a tinpot tyrant has

deliberately loosed a war of conquest and reconquest. In West

Africa a vicious pestilence spreads ever faster.

Think only of how often you have seen images of dead children

this summer: strewn across a cornfield in Ukraine, decapitated on a

street in Iraq, blown apart on a beach in Gaza, wounded in a

hospital in Syria, being buried in Liberia. The fate of the girls

kidnapped by Boko Haram in Nigeria is hardly any less horrible. Man

is a wolf to man.

In the world of money you can find plenty to cry about too.

Argentina has defaulted on its debt. Britain’s national debt has

doubled in four years. The Eurozone is in permanent recession and

teeters on the brink of its next crisis. Stock markets are

wobbling.

All true and all horrible. But the world is always full of

atrocity, violence, death and debt. Are things really worse this

year or are we journalists just reporting the clouds in every

silver lining? Remember the media does not give a fair summary of

what happens in the world. It tells you disproportionately about

the things that go badly wrong. If it bleeds, it leads, as they say

in newspapers. Good news is no news.

So let’s tot up instead what is going, and could go, right.

Actually it is a pretty long list, just not a very newsworthy one.

Compared with any time in the past half century, the world as a

whole is today wealthier, healthier, happier, cleverer, cleaner,

kinder, freer, safer, more peaceful and more equal.

The average person on the planet earns roughly three times as

much as he or she did 50 years ago, corrected for inflation. If

anything, this understates the improvement in living standards

because it fails to take into account many of the incredible

improvements in the things you can buy with that money. However

rich you were in 1964 you had no computer, no mobile phone, no

budget airline, no Prozac, no search engine, no gluten-free food.

The world economy is still growing every year at a furious lick —

faster than Britain grew during the industrial revolution.

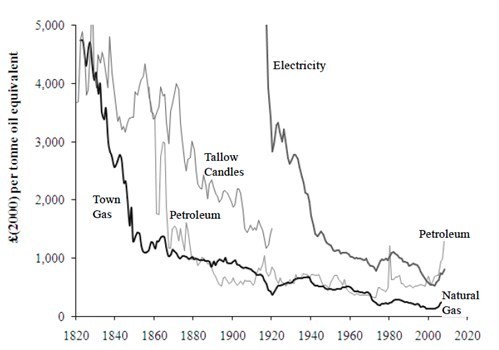

Here's Max Roser's chart of the decline in the price of light

over two centuries:

The average person lives about a third longer than 50 years ago

and buries two thirds fewer of his or her children (and child

mortality is the greatest measure of misery I can think of). The

amount of food available per head has gone up steadily on every

continent, despite a doubling of the population. Famine is now very

rare. The death rate from malaria is down by nearly 30 per cent

since the start of the century. HIV-related deaths are falling.

Polio, measles, yellow fever, diphtheria, cholera, typhoid, typhus

— they killed our ancestors in droves, but they are now rare

diseases.

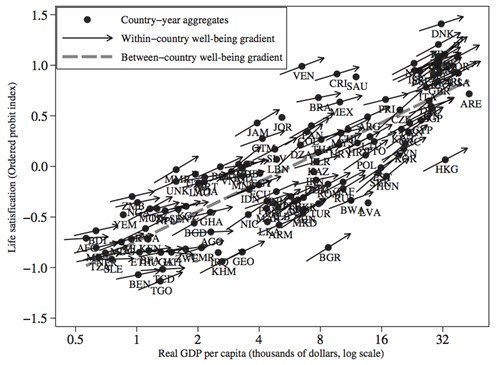

We tell ourselves we are miserable, but it is not true. In the

1970s there was a study that claimed to find that people grew less

happy as they got richer, but it was based on faulty data. We now

know that on the whole people are more satisfied with life as they

get wealthier, a correlation that holds between countries, within

countries and within lifetimes. Anyway, it’s better to be well fed,

healthy and unhappy than hungry, sick and unhappy. Here's Roser's

chart of happiness data:

Education

Education

is in a mess and everybody’s cross about it, but consider: far more

people go to school and stay there longer than they did 50 years

ago. Besides, through a mysterious phenomenon called the Flynn

effect, IQ scores keep going up everywhere, especially in those

topics that have least to do with education, probably thanks to

better food, richer upbringing and so forth.

The air is much cleaner than when I was young, with smog largely

banished from our cities. Rivers are cleaner and teem with otters

and kingfishers. The sea is still polluted and messed with in every

part of the world, but there are far more whales than there were 50

years ago. Forest cover is increasing in many countries and the

pressure on land to grow food has begun to ease.

We think we are getting ever more selfish, but it is not true.

We give more of our earnings to charity than our grandparents did.

Violent crimes of almost all kinds are on the decline — murder,

rape, theft, domestic violence. So are capital and corporal

punishment and animal cruelty. We are less prejudiced about gender,

homosexuality and race. Paedophilia is no more prevalent, just

hushed up less.

Despite all the illiberal things our governments still try to do

to us, freedom is on the march. When I was young only a few

countries were democracies; the rest were run by communist or

fascist despots. Today there’s only a handful of the creeps left —

they could all meet in a pub: fat Kim, Castro the brother, Mugabe,

a couple of central Asians, the blokes from Venezuela and Bolivia,

the Belorussian geezer. Putin’s applying for membership. The

Chinese one no longer shows up.

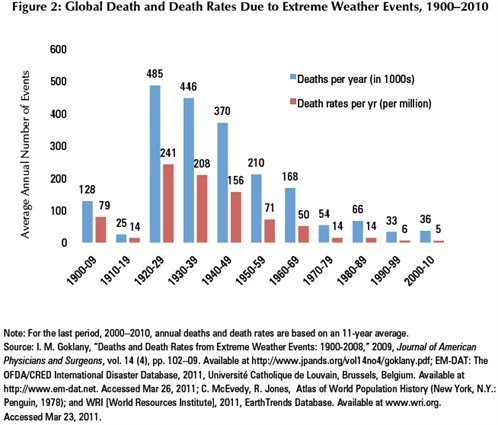

The weather is not getting worse. Despite what you may have

read, there is no global increase in floods, cyclones, tornadoes,

blizzards and wild fires — and there has been a decline in the

severity of droughts. If you got the opposite impression, it’s

purely because of the reporting of natural disasters, which has

become a lot more hysterical. Besides, thanks to better

infrastructure, communications and technology, there has been a

steep decline in deaths due to extreme weather.

Globally, your probability of dying as a result of a drought,

flood or storm is 98 per cent lower than it was in the 1920s. As

Steven Pinker documented in his book The Better Angels

of Our Nature, the number of deaths in warfare is also

falling, though far more erratically. The ten years 2000-10 was the

decade with the smallest number of deaths in warfare since records

began in the 1940s. That may not last — indeed, it is looking like

this decade may be worse. But it may be better.

Here's Goklany's data on global deaths from extreme weather:

As for inequality, the world as a whole is getting rapidly more

equal in income, because people in poor countries are getting

richer at a more rapid pace than people in rich countries. That has

now been true for two decades, but it has accelerated since the

great recession. The GDP per capita of Mozambique is 60 per cent

higher than it was in 2008; that of Italy is 6 per cent lower. A

country like Mozambique has been out of the headlines recently and

now you know why: things are mostly going right there.

Writing my book The Rational Optimist in the

middle of a great recession that seemed to be bringing the world

economy to its knees was brave to the point of foolhardiness. But

if anything I was too cautious. The world bounced back from that

recession far faster than I expected and the pace of innovation and

improvement redoubled.

Britain, too, did better than I feared. We are growing faster

than any other major economy, we have seen the unemployment rate

defy even the most cheery forecasts in its rate of fall and we have

kept the country safer from terrorism than was true for most of my

life. Technologies that seem indistinguishable from magic keep

falling cheaply into our hands.

Of course, like anybody I can still talk myself into gloom.

Scotland could break away. Militant Islam could tear our

communities apart. European bureaucrats could strangle innovation

even more than they do already. When asked what I most worry about,

I always reply “bureaucracy and superstition” because these are

what brought down previous civilisations in Ming China or Abbasid

Arabia.

Be warned that being cheerful guarantees you will never be taken

seriously. The philosopher John Stuart Mill said: “Not the man who

hopes when others despair, but the man who despairs when others

hope, is admired by a large class of persons as a sage.”

August 14, 2014

Gamekeepers are conservationists

My column in the Times on 11th August:

Tomorrow sees the start of the red grouse shooting

season, a sport under attack as never before, with a petition to

ban it, and campaigns to get supermarkets to stop selling grouse

meat.

As somebody who lives in the rural north and knows the issue at

first hand, I am in no doubt that the opponents of grouse shooting

have it backwards. On both economic and ecological grounds, the

shooting of grouse is the best conservation practice for the

heathery hills of Britain. If it were to cease, most

conservationists agree that not only would curlews, lapwings and

golden plover become much scarcer, even locally extinct, but much

heather moorland would be lost to forest, bracken, overgrazing or

wind farms.

Be in no doubt: management for grouse is conservation. The

owners spend money to maintain the heather moors that constitute an

ecosystem found almost nowhere other than Britain. They prevent

overgrazing, re-establish heather, remove plantations of non-native

sitka spruce, eradicate bracken, manage drainage, periodically burn

long heather, kill foxes and crows, refuse to build subsidised wind

farms, and thus maintain the great open spaces of the Pennines and

parts of Scotland where people are free to walk. In the past decade

alone, moorland owners have regenerated 57,000 acres of

heather.

More than £50 million is spent on conservation by grouse moor

owners every year. That’s roughly twice as much as the Royal

Society for the Protection of Birds devotes to its entire

conservation efforts. There is no way the taxpayer would or should

stump up that kind of cash to look after heather moors. But

somebody has to: there is no such thing as a natural ecosystem in

this country and conservation requires human intervention.

Grouse moor owners recoup some of their costs by leasing

shooting to wealthy clients, who often fly in from abroad, fill the

local hotels and create crucial local employment. In the economy of

many Pennine dales, grouse shooting is irreplaceable, adding more

than £15 million a year nationally and supporting 1,500 full-time

jobs. It redistributes money from hedge-fund managers in the south

and overseas to some of the poorest parts of rural Britain. Much as

you might wish them to, rich folk won’t spend lots of money in the

Pennines to watch rare birds; but they will to shoot grouse.

Astoundingly, golden plover, curlews and lapwings, the three

most iconic wading birds of the uplands, live at five times the

density and have more than three times the breeding success on

moors with gamekeepers compared with moors without gamekeepers.

That this is because of gamekeeping was confirmed in a series of experiments by the

Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust near Otterburn in which

matching areas of moor were either keepered or not, then swapped

around after four years.

These birds would be at risk of dying out if it were not for

gamekeepers, as would black grouse, ring ouzels and merlins.

Nesting on or near the ground, such birds are vulnerable to foxes

and crows that take their young. With unnaturally high numbers of

foxes and crows in Britain — because of human roadkill and garbage

— the only way the birds can thrive is if somebody controls the

numbers of crows and foxes. The RSPB knows this and kills both

species on some of its reserves.

As a result, grouse moors in spring are alive with the calls of

birds, whereas the moors that are not managed for grouse are

ornithological deserts. In Wales, for example, lots of conservation

bodies try to manage the hills for birds, but curlews and golden

plover are very scarce, black grouse non-existent — in sharp

contrast to the grouse-rich Pennines. One grouse moor owner I spoke

to last week said he was happy to challenge the RSPB to an

ornithological audit by a neutral body of its upland reserves

versus his grouse moor.

The RSPB argues that the hen harrier, a hawk that preys on

grouse and breeds on moors, is under threat of extinction, because

gamekeepers persecute it. Yesterday saw a damp day of protest on

its behalf. In fact the British hen harrier population is stable at

about 630 pairs and is much higher than it was 100 years ago when

these birds were confined mainly to islands like the Orkneys.

Most of them are in Scotland. The only three successful pairs in

England this year were on or next to managed grouse moors. They are

not breeding on the RSPB’s English reserves because they too are

vulnerable to fox predation, so they need gamekeepers as much as

curlews do. On a Pennine grouse moor there is ample food — grouse

and other birds. On a Welsh bird reserve there’s just the odd

meadow pipit to eat. Because hen harriers breed in colonies, as a

1990s experiment at Langholm in Scotland found, they can quickly

build up (to 20 pairs in that case) and destroy the economy and

jobs on the grouse moor. The harriers themselves would then

collapse in numbers for lack of food. By the end of the experiment,

hen harriers at Langholm were back to two pairs.

You can see why gamekeepers dislike the idea of being done out

of a job by a bird that cannot thrive without their protection;

little wonder that some must occasionally be tempted to deter or

even kill harriers. A sensible compromise is on the table, and moor

owners are ready to sign up to it: they would allow low densities

of harriers on grouse moors, removing the excess chicks to

repopulate Wales or Cornwall, and providing “diversionary feeding”.

Everybody gains. All that’s needed is the RSPB’s agreement, but it

is being obdurate and demanding unworkable preconditions.

The red grouse, the bird at the heart of all this, is an amazing

creature. It’s wholly dependent on grazing heather, it cannot

survive in captivity, it lures people to invest heavily in

conservation in the north, which supports the economy and benefits

other wildlife, and it’s found nowhere else in the world — unlike

the hen harrier, which is common across two continents. The grouse

population can be heavily cropped, just like sheep, to provide

fine, free-range meat.

The campaign against grouse shooting makes no ecological or

economic sense. Surely it is not a cynical attempt to raid urban

wallets with an emotive anti-rich campaign like the RSPCA’s

campaign against foxhunting? Surely not.

-----

Post script: The data on the effect of gamekeepers on the

breeding success of round nesting birds are truly striking. In the

charts below, the red bars are with gamekeeping, the blue bars

without. (Source: here)

This chart shows the change in abundance as a result of the

introduction of gamekeeping:

August 12, 2014

Reasons to be fearful about Ebola

My Times column on Ebola:

As you may know by now, I am a serial debunker of

alarm and it usually serves me in good stead. On the threat posed

by diseases, I’ve been resolutely sceptical of exaggerated scares

about bird flu and I once won a bet that mad cow disease would

never claim more than 100 human lives a year when some “experts”

were forecasting tens of thousands (it peaked at 28 in 2000). I’ve

drawn attention to the steadily falling mortality from malaria and

Aids.

Well, this time, about ebola, I am worried. Not for Britain,

Europe or America or any other developed country and not for the

human race as a whole. This is not about us in rich countries, and

there remains little doubt that this country can achieve the

necessary isolation and hygiene to control any cases that get here

by air before they infect more than a handful of other people — at

the very worst. No, it is the situation in Liberia, Sierra Leone

and Guinea that is scary. There it could get much worse before

it

gets better.

This is the first time ebola has got going in cities. It is the

first time it is happening in areas with “fluid population

movements over porous borders” in the words of Margaret Chan, the

World Health Organisation’s director-general, speaking last Friday.

It is the first time it has spread by air travel. It is the first

time it has reached the sort of critical mass that makes tracing

its victims’ contacts difficult.

One of ebola’s most dangerous features is that kills so many

health workers. Because it requires direct contact with the bodily

fluids of patients, and because patients are violently ill, nurses

and doctors are especially at risk. The current epidemic has

already claimed the lives of 60 healthcare workers, including those

of two prominent doctors, Samuel Brisbane in Liberia and Sheik Umar

Khan in Sierra Leone. The courage of medics in these circumstances,

working in stifling protective gear, is humbling.

Inevitably, some health workers are fleeing the affected areas

and inevitably many families of victims are coming to see the

isolation wards as places of death to which they do not want their

loved ones taken. It does not help that doctors and hospitals are

now so associated with the disease that machete-wielding villagers

in Guinea have been refusing to allow doctors to enter some areas,

on the suspicion that they were bringing the disease.

So no wonder Dr Chan says the outbreak “is moving faster than

our efforts to control it. If the situation continues to

deteriorate, the consequences can be catastrophic in terms of lost

lives but also severe socio-economic disruption.” There is little

doubt that the ebola epidemic will have huge indirect effects,

through interrupting treatment and prevention for other serious

diseases, as well as through the dislocation of the economy of west

Africa.

Consider just one case, that of the woman who probably

first brought the virus to Liberia in March when she returned from

Guinea feeling unwell. She was cared for by her sister till she

died. The sister felt ill and took a communal taxi to Liberia’s

capital Monrovia on the way see her husband, which resulted in the

deaths of five other passengers in the taxi. She rode pillion on a

motorbike some of the way and the driver has not been traced. That

sort of thing is happening all the time.

I still maintain that ebola is very unlikely to cause a global

pandemic. As a disease of human beings it is too quick, too

virulent, too easy to contain — for its own good. With reasonable

precautions like hygiene and isolation, strictly enforced, it

fizzles out fast. This is true, not just of ebola, but of all the

haemorrhagic fevers, like the lassa, hanta and marburg viruses.

These have caught the imagination of scriptwriters because the

deaths they cause are so gory and the prognosis of those infected

so dire. However, they have never managed to create a pandemic —

unless the theory is right that the plague recorded by Thucydides

in 430BC, which supposedly came down the Nile from Africa, was

ebola. Lassa (from rodents) and marburg (from bats) flare up from

time to time in Africa, and hanta (also rodents) killed 121

soldiers during the Korean war.

The first and (until this time) worst recorded outbreak of

ebola, in Yambuku in Congo in 1976, was exacerbated by well-meaning

nuns running a remote clinic. They re-used needles to give quinine

injections to people with malarial symptoms and the early symptoms

of ebola are like malaria. Three quarters of those who died caught

the virus this way; four of the nuns also died. Today, the chances

of health workers making the problem worse are remote.

The more febrile kind of science writer is given to suggesting

that ebola is a sort of revenge from the ravished rainforest for

the destruction we have wrought on it. That is nonsense. Blood

samples from pygmies suggest that ebola outbreaks have been

happening sporadically for a very long time and killing apes as

well as people. If anything, it is intact forests, full of fruit

for bats to feed on, that represent the greatest reservoir. Bats

carry and reproduce the ebola virus very effectively, but are much

less affected by it and they are almost certainly its natural

host.

We do need to treat bats with caution. They have already given

us rabies, marburg virus and a morbillivirus in Australia that is

lethal to horses. Ebola is their deadliest gift. Given that a

quarter of all mammal species are bats, that they often share our

living spaces and they live like us in dense colonies, the chances

are they have more viruses to pass on. In the 1990s, a woman in an

animal sanctuary in Australia died from a bat-borne lyssavirus. (I

would forbid zoos and animal sanctuaries from handling bats in

tropical regions.)

Liberia and Sierra Leone are two of only six countries in the

world whose average per capita income is lower today than it was 50

years ago, and that is why they are so vulnerable to this epidemic.

The key lesson is not to slow or reverse development in rural

Africa. Quite the opposite. The sooner we can engage more of the

citizens of Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone in the global economy,

so they can get jobs in urban areas, afford decent healthcare and

begin to eat fast food rather than bushmeat, the better.

August 4, 2014

The coup d'etat of 1714 - when the Whigs won

I have a piece in the latest Spectator on the

tercentenary of King George I:

The centenary of the start of the first world war is getting

much more attention than the tricentenary of the accession of

George I, which also falls this week. As far as I can tell, no new

biographies of the first Hanoverian king are imminent, whereas

books on the great war are pouring forth. You can see why. The

replacement of a plump, if benign, queen by an ‘obstinate and

humdrum German martinet with dull brains and coarse tastes’

(Winston Churchill’s words), who presided over a huge financial

scandal and died unlamented after a short reign, need hardly detain

us.

But forget the royals and focus on what we might call the

reshuffle among politicians that accompanied the change. Here’s how

Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, described the last week of

July 1714 in a letter to Dean Swift: ‘The Earl of Oxford was

removed on Tuesday. The Queen died on Sunday. What a world this is,

and how does fortune banter us.’

The fall of the Jacobite-leaning Tories, led by Bolingbroke and

his rival and former friend Oxford, with a coup

d’état in the Privy Council by the Hanoverian-favouring Whigs,

led by the Duke of Shrewsbury, on 30 July turned out to be a key

moment in British history. It was never reversed, despite several

attempts. In its own way it was as significant as 1215 and

1688.

The Tory Bolingbroke, a dazzling orator and spectacular

libertine, had been stuffing positions of power with fellow

Jacobites since becoming secretary of state and overshadowing his

erstwhile ally the Earl of Oxford. But at an emergency privy

council meeting on 30 July following the Queen’s stroke, he found

himself outwitted by Shrewsbury, who unexpectedly summoned two

fellow Whigs, the Dukes of Argyll and Somerset. The council got the

barely conscious Queen to make Shrewsbury Lord Treasurer, then sat

late into the night dispatching messages to alert garrisons and

ensure that the Hanoverian succession was proclaimed.

Had Bolingbroke prevailed at that meeting, we would probably

have had a King James III, though there would almost certainly have

been a civil war (instead of the minor fiasco of the Fifteen).

Britain might have been more absolutist, more French influenced,

more Catholic-tolerant and less commercial. The stirrings of steam

in the north that were to start the industrial revolution — the

first faltering steps to turning heat into work — might have

fizzled. The Act of Union with Scotland, agreed to some years

earlier as part of the English insistence on the Hanoverian

succession, might have unravelled.

At least, so goes conventional wisdom. In Churchill’s words, the

outcome of that long meeting of the privy council was ‘No popery,

no disputed succession, no French bayonets, no civil war’.

However, there is another possibility. When not bonking,

Bolingbroke was a philosopher, a religious free thinker greatly

admired by Voltaire and Alexander Pope. His speeches and writings

were read with avidity by the American founding fathers, who

credited Bolingbroke with the idea that liberty means being free,

‘not of the law but by the law’. He invented the concept of an

official political opposition and saw it as his duty to prevent the

Whigs turning into a perpetual oligarchy. He proposed free trade

with France.

He was, in other words, a great deal more of an Enlightenment

figure than the Whig who replaced him and, thanks to the blind

support of George I and II, dominated politics for 20 years, while

filling his pockets with ill-gotten gains: Robert Walpole.

Thus the cartoon version of history in which Whigs and

Hanoverians brought liberty, parliament, Protestantism and trade,

while Tories and Stuarts would have brought absolutism, Popery and

civil war, may not be right. You cannot quite help wondering if a

Bolingbroke ascendancy might have given England a more vigorous

Enlightenment, too, to rival those in France and Scotland. It has

always puzzled me that the stars of the Enlightenment — Voltaire,

Diderot, Hume, Smith and co. — included plenty of Scots and French,

but no Englishmen.

Had Bolingbroke persuaded James Edward Stuart to turn

Protestant, as he had tried to, then many British people would have

welcomed a Stuart king. The idea of a German-speaking monarch was

not at all popular. Shrewsbury’s coup might well have failed.

As it was, it was a close-run thing. There were plenty of

Protestants who favoured James. I recently found out that my

ancestor, who was Tory mayor of Newcastle that year, refused to

declare the accession of George despite being a staunch Protestant.

A rival faction did declare it, so Richard Ridley sent his thugs to

stamp it out, resulting in a Friday night riot on the Quayside

(nothing much has changed).

Still, it all worked out in the end. Britain may not have loved

its new king, nor the corrupt grandees who ruled in his name and

promptly debauched the currency in the South Sea Bubble. But George

did give sanctuary to Voltaire when he was exiled from France, and

gradually the country did take advantage of the largest free-trade

area in Europe (England and Scotland) to sow the seeds of

prosperity and incubate freedom.

Bolingbroke’s most famous work, The Idea of a Patriot

King, was written at Alexander Pope’s behest much later in

1738 to influence George I’s grandson Frederick, Prince of Wales,

into being a monarch who rose above faction, was a father to his

country and championed trade.

Which, if you think about it, is roughly what we have now.

This article first

appeared in the print edition of The Spectator magazine,

dated 2 August

2014

August 2, 2014

Priorities and goals for aid

My recent essay in the Wall Street Journal

discusses how to prioritise development aid:

In September next year, the United Nations plans to choose a

list of development goals for the world to meet by the year 2030.

What aspirations should it set for this global campaign to improve

the lot of the poor, and how should it choose them?

In answering that question, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

and his advisers are confronted with a task that they often avoid:

setting priorities. It is no good saying that we would like peace

and prosperity to reach every corner of the world. And it is no

good listing hundreds of targets. Money for foreign aid, though

munificent, is limited. What are the things that matter most, and

what would be nice to achieve but matter less?

The origin of this quest for global priorities goes back to

2000, when Mr. Ban's predecessor, Kofi Annan, picked a set of

"Millennium Development Goals," eight challenges to be met by 2015,

which were adopted by world leaders. Although some of these goals

were woolly, the very brevity of the list and the deadline itself

meant that they really did catch the world's imagination and force

the aid industry to be more selective.

Most of the original Millennium Development Goals will have been

met or nearly so by 2015. Since 2000, for example, the number of

people living in extreme poverty and hunger around the world will

have been cut in half—an astonishing achievement. Other goals

included universal primary education, gender equality, reductions

in child mortality, improvements in maternal health, progress

against HIV and malaria, environmental sustainability and (most

vaguely) a "global partnership for development."

The lesson, surely, from this first round of setting development

goals is the need to be even more ruthlessly selective next time. A

list of eight goals is too long for most outsiders to remember.

When I asked several of my colleagues in the British Parliament,

they remembered only three to five. Several development experts I

spoke to say that the new list should have just five discrete,

quantitative, achievable goals.

Only Mr. Ban can make that happen, says Charles Kenny, a senior

fellow at the Center for Global Development in Washington, D.C.,

who observes that you should "never ask a committee to write

poetry." Mr. Kenny told me: "There is one person who can bring the

poetry. The U.N. secretary-general has to edit down with an ax, not

a scalpel. Without strong intervention from Ban Ki-moon, there is

extremely limited prospect for simplification."

Goal: Boost preprimary education,

which costs little and has lifelong benefits by getting children

started on learning. European Pressphoto Agency

So far, however, the process of deciding on the 2030 goals is

short on poetry. There is not just one committee on the job but

several—the most prominent of which is called the Open Working

Group, or OWG, which has already been meeting off and on for more

than two years. The OWG "stream"—and keep in mind that other U.N.

groups are also producing streams of their own—has so far managed

to whittle its list of possible targets down to 169. It is an

absurdly long list, and each time the results of its deliberations

are published, every pressure group checks to make sure its

favorite goal is still in there and makes a fuss if it is not.

What Mr. Ban needs is an objective way of paring down the list.

In doing so, I would recommend to him an unlikely ally: Bjorn

Lomborg, a T-shirt-wearing, vegetarian, Danish political scientist

who shot to fame in 2001 with a book called "The Skeptical

Environmentalist," which infuriated those who support environmental

protection at all costs, including the welfare of the poor.

Mr. Lomborg is the founder of an international think tank called

the Copenhagen Consensus Center. He has invented a useful method

for dispassionately but expertly deciding how to spend limited

funds on different priorities. Every four years since 2004, he has

assembled a group of leading economists to assess the best way to

spend money on global development. On the most recent occasion, in

2012, the group—which included four Nobel laureates—debated 40

proposals for how best to spend aid money.

The goal was simple: to create a cost-benefit analysis for each

policy and to rank them by their likely effectiveness. For every

dollar spent, how much good would be done in the world?

The Copenhagen Consensus Center process has won world-wide

respect for its scrupulously fair methods and startling

conclusions. Its 2012 report, published in book form as "How to

Spend $75 Billion to Make the World a Better Place," came to the

conclusion that the top five priorities should be nutritional

supplements to combat malnutrition, expanded immunization for

children, and redoubled efforts against malaria, intestinal worms

and tuberculosis.

Their point wasn't that these are the world's biggest problems,

but that these are the problems for which each dollar spent on aid

generates the most benefit. Enabling a sick child to regain her

health and contribute to the world economy is in the child's

interest—and the world's.

The numbers produced by this exercise are eye-catching. Every

dollar spent to alleviate malnutrition can do $59 of good; on

malaria, $35; on HIV, $11. As for fashionable goals such as

programs intended to limit global warming to less than two degrees

Celsius in the foreseeable future: just 2 cents of benefit for each

dollar spent.

Nor is this just about the cold tabulation of dollars and cents.

The calculus used by the Copenhagen Consensus also includes such

benefits as avoided deaths and sickness and potential environmental

benefits, including forestalling climate change.

The Copenhagen experts use strips of paper on which are written

different priorities along with cost-benefit ratios, and they are

invited to move them up and down as they debate the academic

evidence. In setting priorities, they also take into account the

feasibility of scaling up interventions and the risk of

corruption.

Of course, when the U.N. is contemplating its choices for the

next set of global development goals, cost-benefit isn't the only

criterion. In South Africa, for instance, HIV is a much bigger

problem than malaria, so different regions will have different

concerns. But ranking the interventions does concentrate the

mind.

Surprising as it may seem, the global-aid industry has rarely

done such cost-benefit analysis. People in this line of work

generally recoil from such rankings as a heartless exercise

implying discrimination against still-worthy global goals. The aid

industry often seems implicitly to take the view that funds are

unlimited and that spending on one priority doesn't crowd out

spending on another. But this is patently not the case: The

problems are far bigger than the available budget and will remain

so even if the world's rich countries ever meet their 35-year-old

goal of spending 0.7% of their GNP on development aid.

In December last year, Mr. Lomborg came to New York to address

the U.N. Open Working Group's ambassadors directly. He handed them

his strips of paper and asked them to put them down in preferred

order. It was an eye-opening exercise in a place where people are

accustomed to saying, in diplomatic earnest, "Everything is

important."

Then, over eight days in June, Mr. Lomborg got a group of 60

leading economists to work through all the OWG's putative

development targets for 2030 (there were more than 200 of them at

the time), making a quick assessment of which were good value for

money. The result, now available online, is a

document that assigns a color code to each target: green

(phenomenal value for money), pale green (good), yellow (fair),

gray (not enough known) and red (poor).

[Here are some of the Copenhagen

Consensus Center group's rankings.]

At the conclusion of this process, the group had 27 "phenomenal"

green values and 23 "poor" red values, with all the rest in

between.

Champions of aid aren't used to having their homework marked in

this stark fashion, and some didn't like it at first. As Ambassador

Elizabeth M. Cousens, the U.S. representative to the U.N. Economic

and Social Council, told Mr. Lomborg, "I really don't like you

putting one of my favorite targets in red." But she added, "I'm

glad you're saying it, because we all need to hear economic

evidence that challenges us."

Having gone through this useful document myself, I found myself

in full sympathy with those forced to choose among them. But at

least this sort of analysis provides some rigor and direction.

What would my own list of five 2030 goals look like, based on

the work of the Copenhagen Consensus group?

1. Reduce malnutrition. When children get better food, they

develop their brains, stay in school longer and end up becoming far

more productive members of society. Every dollar spent to alleviate

malnutrition brings $59 of benefits.

2. Tackle malaria and tuberculosis. These two diseases

debilitate huge populations in poor countries, but they are largely

preventable and curable. In the most harshly affected countries,

two people often do one person's work because one of them is sick.

Benefit to cost ratio: 35 to 1.

3. Boost preprimary education, which costs little and has

lifelong benefits by getting children started on learning. 30 to

1.

4. Provide universal access to sexual and reproductive health,

which would save the lives of mothers and infants while enabling

women to be more economically productive. It would also lower

birthrates (when fewer children die, people have fewer children).

Benefits could be as high as 150.

5. Expand free trade. This isn't considered sexy in the

development industry, and it may seem remote from humanitarian

issues, but free trade often delivers phenomenal improvements to

the welfare of the poor in surprisingly quick time, as the example

of China has demonstrated in recent years. One of the discoveries

of the Copenhagen Consensus process is that incremental goals such

as expanding free trade are often better than supposedly

"transformational" goals. A successful Doha Round of the World

Trade Organization could deliver annual benefits of $3 trillion for

the developing world by 2020, rising to $100 trillion by the end of

the century.

The development goals of least value, according to the

Copenhagen process, include the self-contradictory call for higher

agricultural productivity with less environmental impact. Other bad

investments are less obvious but would actually hurt the poor. For

example, equal access to affordable tertiary education may sound

good in principle, but in many developing countries, it amounts to

a policy of having the mass of poor people pay for the college

education of the rich. Other goals—such as "sustainable

tourism"—are simply too narrow and ill-defined to merit

consideration on a list of urgent priorities.

One much-favored goal in the list generated by the U.N.'s Open

Working Group comes out especially badly: the idea of providing

gender-disaggregated data to help women. Not only do we have much

of the data (and it is very costly to gather more), but how, say

the Copenhagen experts, would you define the gender-disaggregated

value of a cow owned by a family of five?

Those who fear that the rankings might reflect Mr. Lomborg's own

prejudices will be relieved. He convened the economists, to be

sure, but they are the ones who did the color coding.

Mr. Lomborg accepts the basic conclusions of today's climate

science, but he is known to be skeptical about many current

policies to avert climate change. Still, the experts he brought

together conclude that phasing out fossil-fuel subsidies is a

"phenomenal" value. They also find excellent value in programs

meant to develop resilience and adaptive capacity in response to

climate-induced hazards.

But they judge it poor value, for the world's poor, to attempt

either to double the share of renewable energy in the global energy

mix or to hold the increase in global average temperature below a

certain level in accordance with international agreements. This is

because the experts think that allowing emissions to rise initially

while investing in rapid advances in energy technology is a much

better idea than trying to limit emissions now with today's

expensive renewables.

Indeed, one of the world's most pressing health problems, and

the one most conspicuously missing from Mr. Annan's original

development goals in 2000, is the annual death toll of more than

four million people due to indoor air pollution. This enormous,

abiding problem is attributable to the fact that so many of the

world's poor lack access to affordable (that is,

fossil-fuel-generated) electricity and therefore cook over burning

wood or dung.

This most recent exercise by the Copenhagen Consensus was, Mr.

Lomborg admits, "quick and dirty," intended to catch the attention

of the Open Working Group before it wraps up its work for the

summer. But in the coming months, Mr. Lomborg's group will publish

thousands of peer-reviewed pages, describing costs and benefits for

all the most important U.N. targets. With the help of three Nobel

Laureates, the group will produce a definitive report with ranked

priorities and deliver it to the U.N.

Figuring out the best way to help the world's poor isn't like

solving a math problem. There are not right and wrong answers. But

there are better and worse answers, and the only way to assign

those priorities is to set aside our sentimental commitments and do

the hard work of assessing costs and benefits.

July 31, 2014

Renewable energy is not working

My Times Column explores why renewable energy has

been so disappointing.

On Saturday my train was diverted by engineering

works near Doncaster. We trundled past some shiny new freight

wagons decorated with a slogan: “Drax — powering tomorrow: carrying

sustainable biomass for cost-effective renewable power”.

Serendipitously, I was at that moment reading a report by the chief scientist at the

Department of Energy and Climate Change on the burning of wood in

Yorkshire power stations such as Drax. And I was feeling

vindicated.

A year ago I wrote in these pages that it made no sense for

the consumer to subsidise the burning of American wood in place of

coal, since wood produces more carbon dioxide for each

kilowatt-hour of electricity. The forests being harvested would

take four to ten decades to regrow, and this is the precise period

over which we are supposed to expect dangerous global warming to

emerge. It makes no sense to steal beetles’ lunch, transport it

halfway round the world, burning diesel as you do so, and charge

hard-pressed consumers double the price for the power it

generates.

There was a howl of protest on the letters page from the chief

executive of Drax power station, which burns a million tonnes of

imported North American wood a year and plans to increase that to 7

million tonnes by 2016. But last week, Dr David MacKay’s report

vindicated me. If the wood comes from whole trees, as much of it

does, then the effect could be to increase carbon dioxide

emissions, he finds, even compared with coal. And that’s allowing

for the regrowth of forests.

Despite the best efforts of the Conservatives to rein in their

Lib Dem colleagues, the renewable-energy bandwagon careers onward,

costing ever more money and doing real environmental harm, while

producing trivial quantities of energy and risking blackouts next

winter. People keep telling me it’s no good being rude about all

renewables: some must be better than others. Well, I’m still

looking:

Tidal power remains a (literal) non-starter; if you ask

ministers why nothing has been built, they say it’s not for want of

proffering ludicrously generous subsidies on our behalf. Yet still

no takers.

Wave power: again, the sky’s the limit for what the government

will pay if you can figure out how to make dynamos and generators

survive the buffeting of waves, corrosion of salt and encrustation

of barnacles. Nothing doing.

Geothermal: perhaps great potential in the future for heating

homes through district heating schemes, though expensive here

compared with Iceland, but not much use for electricity. Air-source

and ground-source heat pumps, all the rage a few years ago, have

generally proved more costly and less effective than advertised,

but they are getting better. Trivial contribution so far.

Solar power: one day soon it will make a big impact in sunny

countries, and the price is falling fast, but generating for the

grid in cloudy Britain where most power is needed on dark winter

evenings will probably never make economic sense. Covering fields

in Devon with solar panels today is just ecological and economic

vandalism. Solar provides about a third of one per cent of world

energy.

Offshore wind: Britain is the world leader, meaning we are the

only ones foolish enough to pay the huge subsidies (treble the

going rate for electricity) to lure foreign companies into tackling

the challenge of erecting and maintaining 700ft metal towers in

stormy seas. The good news is that the budget for subsidising

offshore wind has almost run out. The bad news is that it is

already costing us billions a year and ruining coastal views.

Onshore wind: one of the cheapest renewables but still twice as

costly as gas or coal, it kills eagles and bats, harms tourism,

divides communities and takes up lots of space. The money goes from

the poor to the rich, and the carbon dioxide saving is tiny,

because of the low density of wind and the need to back it up with

diesel generators. These too now need subsidy because they cannot

run at full capacity.

Hydro: cheap, reliable and predictable, providing 6 per cent of

world energy, but with no possibility for significant expansion in

Britain. The current vogue for in-stream generation in lowland

streams in England will produce ridiculously little power while

messing up the migration of fish.

Anaerobic digestion: a lucrative way of subsidising farmers (yet

again) to grow perfectly good food for burning instead of eating.

Contrary to myth, nearly all the energy comes from crops such as

maize (once fermented into gas), not from food waste.

Expensive.

Waste incineration: a great idea. Yet we are currently paying

other countries to take it off our hands and burn it overseas. If

instead we burned it at home, we would make cheap, reliable

electricity. But Nimbys won’t let us.

Over the past ten years the world has invested more than $600 billion in wind power

and $700 billion in solar power. Yet the total contribution those

two technologies are now making to the world primary energy supply is still less than

2 per cent. Ouch.

If we had spent that sum on research, and steadily replaced coal

with gas as a source of electricity, we would have done far more to

cut carbon emissions and kept prices low. A new report by Charles Frank of the Brookings

Institution has come to the startling conclusion that if you encourage gas

to replace coal, you get fewer emissions per dollar spent than if

you use wind or solar.

In Mr Frank’s words: “Solar and wind facilities suffer from

a very high capacity cost per megawatt, very low capacity factors

and low reliability, which result in low avoided emissions and low

avoided energy cost per dollar invested.” In short, we are picking

losers.

I would not suggest Drax goes back to burning only coal, partly

because I have a vested interest in the coal industry and partly

because more than 40 per cent of the coal we burn in this country

comes from Russia, so we are more exposed to Vladimir Putin for our

coal than for our gas. The answer is staring us in the face. Gas is

the cheapest clean way of making electricity, and we are sitting on

one of the world’s richest shale-gas fields. Yet investment in

gas-fired power is deterred by the government’s preference for

renewables.

July 24, 2014

Atheists and Anglicans could unite against intolerance

My Times column is on religion in schools:

We now know from Peter Clarke’s report, published today but

leaked last week, that there was indeed “co-ordinated, deliberate

and sustained action to introduce an intolerant and aggressive

Islamist ethos into some schools” in Birmingham.

Whistleblowers first approached the British Humanist Association

in January with such allegations, weeks before the appearance of

the Trojan Horse letter. The BHA (of which I should declare I am a

“distinguished supporter” though I’ve never done much to deserve

this accolade) properly passed on the information to the Department

for Education.

Pavan Dhaliwal, of the BHA, has made the awkward point that much

of what went on in the Park View Trust schools would have been

permissible if the schools had been designated “faith schools”. The

BHA campaigns against the very existence of state-funded faith

schools, pointing out that Britain is one of only four countries in

the world to allow religious selection in admissions to

state-funded schools. The others are Estonia, Ireland and

Israel.

In short, we can hardly be shocked to find religious

indoctrination going on in some schools if we encourage segregation

on the basis of faith. Since 2000 the proportion of secondary

schools that are legally religious has increased by 20 per cent,

and their freedom of action has greatly increased. The best way to

prevent young girls in Birmingham being told that “if a woman said

no to sex with her husband then angels would punish her from dusk

till dawn”, as happened in Birmingham, is to leave religious

practice — though not education about religion — out of school

altogether.

I know such a view is considered intolerant, even bigoted — a

charge frequently levelled at non-believers. “The trouble with that

Richard Dawkins”, a lay preacher said to me some years ago, “is

that he’s welcome to his views, but I don’t like him forcing them

on others.” Passing up the temptation to point out his own

hypocrisy as a preacher, I gently reminded him that, whereas I had

to go to prayers or chapel every day at my school, nobody has ever

been forced to read Richard Dawkins on atheism.

August sees a

great global gathering of atheists and humanists in Oxford for

the World Humanist Congress, the first time this body has met in

Britain since 1978. Professor Dawkins will be on the stage, along

with a galaxy of infidel stars, including the Nobel prizewinner

Wole Soyinka, Philip Pullman, Jim al-Khalili, Nick Clegg and the

Bangladeshi blogger Asif Mohiddun, who was attacked and stabbed in

the back, shoulder and chest by a group of radical religious

fundamentalists because of his criticism of Islam.

Not there in person will be Mubarak Bala, the Nigerian detained on a

psychiatric ward for being an atheist, whose case has been

highlighted by the International Humanist Ethical Union. His father

had Mr Bala sectioned for expressing doubts about religion and he

got out, two weeks ago, only because of a strike at the hospital.

Nor will Alexander Aan— the scientist in Indonesia who

was arrested and imprisoned for two years for expressing doubts

about God — be present. But many similar activists from Africa and

Asia will be there, including Gululai Ismail, who runs the Aware

Girls project in northwest Pakistan, challenging patriarchy and

religious extremism, and under constant threat of violence. It was

her organisation that Malala Yousafzai was working for when shot by

the Taliban.

It is clear that the kind of rational scepticism that we British

have been tolerating for three centuries is resulting in terrible

persecution throughout the Muslim world, and it is getting worse. I

say we tolerate atheism here, and we do, but still grudgingly.

Atheists lose count of the number of times we are told we are

lacking in imagination and wonder, or that we just don’t see the

human need for spirituality, or that we must have trouble

justifying morality.

British Christians are generally prepared to be much ruder about

atheism than they are about Islam. Some of the stuff Professor

Dawkins has to read about himself would be condemned as hate speech

if said about a Muslim. This is partly because atheists do not

threaten our critics with violence, whereas any “Islamophobic”

remark or cartoon leads to death threats. It is also because

Christians are continually trying to make common cause with other

religions in defence of “faith” as a source of morality and harmony

in the world. Did I dream it, or did a recent archbishop muse about

the virtues of Sharia?

Anglicanism is a mild and attenuated form of the faith virus and

may even act as a vaccine against more virulent infections, but

Christianity is becoming more evangelical in response to its global

competition with Islam. This has always happened in religious

history: where religions compete, they become more extreme — the

crusades, the 30-years war, Ulster.

So for all the pious talk of “faith communities”, the two

religions are not on the same side. To combat the rise of radical

Islam and radical Christianity, we should try the secular,

free-thinking approach. Mild Anglicanism should make common cause

with humanists in defence of tolerance.

The experience of the past three centuries is that if lots of

people stop believing in gods, they do not become less moral. On

the contrary, the number of people attending church has gone down

at about the same rate as the number of people who commit violent

crimes. I am not suggesting a causal connection — though I suspect

religious people would if the trends were different — but these

facts give the lie to the idea that godlessness leads to

immorality. (And don’t tell me that communist regimes were

irreligious — they enforced a worship of their leaders with all the

techniques and fervour of religion.)

Unlike the almost triumphalist mood among atheists in the 1960s,

when Francis Crick foresaw the end of religion and started a

competition for what to do with the college chapels in Cambridge,

rationalists no longer expect to get rid of religion altogether by

explaining life and matter: they aim only to tame it instead, and

to protect children from it. Nonetheless, they are slowly winning:

witness the fact that more than 12 per cent of

funerals in this country are now humanist in some form. And

humanists are showing no signs of turning intolerant, let alone

violent.

July 17, 2014

On Slippery Slopes

My Times column tackles the misleading metaphor of the slippery

slope:

Who first thought up the metaphor of the slippery

slope? It’s a persistent meme, invoked in many a debate about

ethics, not least over the assisted dying bill for which I expect

to vote in the House of Lords on Friday. But in practice, ethical

slopes are not slippery; if anything they are sometimes too

sticky.

It is in genetics and reproduction that the slippery slope

argument gets used most relentlessly. The latest science to suffer

from the slippery-slope metaphor is mitochondrial replacement

therapy (MRT), a substantially British innovation, which promises

to cure human mitochondrial diseases by replacing the mother’s cell

batteries with those from a donor. It will be up to regulators to

decide if the technique is safe, but first it is up to parliament

to decide if it is ethically acceptable.

The only real objection to this intervention to allow certain

people to have their own children without horrible diseases is that

it is, in the words of one critic, “a slippery slope to

human germline modification”. Change the 0.002 per cent of genes

that are in the mitochondrion and what’s to stop somebody one day

changing the 99.998 per cent of genes in the nucleus of the

egg?

Here’s a perennial opponent of genetics, David

King, of Human Genetics Alert, on MRT: “Once we’ve crossed this

crucial ethical line, which says that we shouldn’t create babies

that have been genetically altered, it becomes very difficult to

then stop when the next step is wanted and then the next step after

that and we will eventually get to this future that everyone wants

to avoid of designer babies.”

But why would it be very difficult to stop? If MRT is legalised,

it would still be illegal to use it for any purpose other than

prevention of mitochondrial genetic disease.

A real slippery slope is a muddy hillside where one small,

apparently safe, step can lead to a slide to the bottom on your

backside. This is because, the physicists tell me, the static

co-efficient of friction is greater than the kinetic co-efficient

of friction, so it takes more force to start a bottom sliding than

to keep it going.

Look around current debates and it seems we stand atop veritable

mountain ranges of slippery slopes. Assisted dying will lead to

widespread euthanasia. Gay marriage will lead to approved

bestiality. Artificial life will lead to biological warfare. But

metaphors can mislead. There is no equivalent in the world of

politics to that change in the co-efficient of friction that

happens on muddy hillsides. It is easy to stop half way down a

moral slope; it’s hard not to. Each step meets fierce opposition

however well the previous step went.

When we do carry on down an ethical slope, progressively

changing the moral code, it’s not because it is slippery and we

wish we could stop, but because we have collectively decided we

want to go further at each stage. The Great Reform Bill was a step

on the road to universal adult suffrage, as many conservatives at

the time feared it would be, but it was hardly a slippery slope,

more of a lengthy struggle. The legalisation of homosexuality was

indeed a step on the road to gay marriage, as many religious people

feared at the time, but only because society chose to take each

subsequent step.

Over 40 years we have repeatedly been promised that bad things

will come of interfering in reproduction, but so far the good has

vastly outweighed the bad. The invention of in-vitro fertilisation

in the 1970s was much feared by many people as the precursor to

eugenics — people would use the technology to have superior babies

by using the sperm of celebrities. Wrong: the demand for

high-performance donor fathers is all but non-existent; the

technology is used almost entirely to help people have their own

babies, to cure the cruel disease of infertility.

Then in the 1980s research on embryos was going to lead

inexorably to the cheapening of life. It did the opposite, leading

to the development of techniques such as pre-implantation genetic

diagnosis (PGD), in which inherited diseases could be avoided,

reducing misery for thousands. But then PGD was going to lead to

eugenics for the rich, who would pick the best genes for their

babies. Not so. There is very little interest in using PGD to

“improve” normal genomes rather than avoid faulty ones.

In the 1990s, there was one technology that overreached. Gene

therapy — the attempt to replace a faulty gene in a particular

tissue using a virus to deliver a new version — did make an early

mistake, contributing to the deaths of some patients. But now the

technique is safely doing good on a growing scale.

Earlier this year, it was announced that six people with a

previously incurable form of blindness had improved their sight

after gene therapy. This follows successful gene-therapy trials on

children with various life-threatening inherited conditions.

After so many decades of seeing genetics and reproductive

technologies prove more beneficial and less open to abuse than

expected, you might think an intervention such as MRT had earned

the benefit of the doubt. Indeed, you might think that the

conservative side of this debate would have seen enough to change

its mind and recognise that the alleviation of suffering should

take priority over the pious recitation of moral platitudes and

appeals to faulty metaphors about muddy hillsides.

You might even, in a sense, think that the slope should be a bit

more slippery. If each step proves more beneficial and less harmful

to humanity than expected, then the next step should be taken

faster. But this is not the way such debates work. The track record

of previous innovations in medicine is ignored when we decide each

new possibility. The slope is sticky, not slippery.

It staggers me that the resistance to new techniques of genetic

and reproductive medicine comes mainly from the right, and the

religious right at that. Where, pray, in the Bible or Koran does it

say that it is better that a child — or an old person — should

suffer than that the sanctity of natural genomes and natural

ailments be interfered with? And all just in case some vague and

implausible crime be facilitated in the distant future. Slippery

slopes are red herrings.

July 9, 2014

The BBC and balance

My Times column on the BBC's unbalanced

environmental coverage:

The BBC’s behaviour grows ever more bizarre.

Committed by charter to balanced reporting, it has now decided

formally that it was wrong to allow balance in a debate between

rival guesses about the future. In rebuking itself for having had

the gall to interview Nigel Lawson on the Today programme about

climate change earlier this year, it issued a statement containing

this gem: “Lord Lawson’s views are not supported by the evidence

from computer modelling and scientific research.”

The evidence from computer modelling? The phrase is an oxymoron.

A model cannot, by definition, provide evidence: it can provide a

prediction to test against real evidence. In the debate in

question, Lord Lawson said two things: it was not possible to

attribute last winter’s heavy rain to climate change with any

certainty, and the global surface temperature has not warmed in the

past 15 to 17 years. He was right about both, as his debate

opponent, Sir Brian Hoskins, confirmed.

As for the models, here is what Dr Vicky Pope of the Met Office

said in 2007 about what their models predicted: “By 2014, we’re

predicting that we’ll be 0.3 degrees warmer than 2004. Now just to

put that into context, the warming over the past century and a half

has only been 0.7 degrees, globally . . . So 0.3 degrees, over the

next ten years, is pretty significant . . . These are very strong statements about what will happen over the

next ten years.”

In fact, global surface temperature, far from accelerating

upwards, has cooled slightly in the ten years since 2004 on most

measures. The Met Office model was out by a country mile. But the

BBC thinks that it was wrong even to allow somebody to challenge

the models, even somebody who has written a bestselling book on

climate policy, held one of the highest offices of state and

founded a think-tank devoted to climate change policy. The BBC

regrets even staging a live debate between him and somebody who

disagrees with him, in which he was robustly challenged by the

excellent Justin Webb (of these pages).

And why, pray, does the BBC think this? Because it had a

complaint from a man it coyly describes as a “low-energy

expert”,

Mr Chit Chong, who accused Lord Lawson of saying on the

programme that climate change was “all a conspiracy”.

Lawson said nothing of the kind, as a transcript shows. Mr

Chong’s own curriculum vitae boasts that

he “has been active in the Green party for 25 years and was the

first Green councillor to be elected in London”, and that he “has a

draught-proofing and insulation business in Dorset and also works

as an environmental consultant”.

So let’s recap. On the inaccurate word of an activist politician

with a vested financial and party interest, the BBC has decided

that henceforth nobody must be allowed to criticise predictions of

the future on which costly policies are based. No more appearances

for Ed Balls, then, because George Osborne’s models must go

unchallenged.

By the way, don’t bother to write and tell me that Lord Lawson

is not a scientist. The BBC also rebuked itself last week for

allowing an earth scientist with dissenting views on to Radio 4.

Professor Bob Carter was head of the department of earth sciences

at James Cook University in Australia for 17 years. He’s published

more than 100 papers mainly in the field of paleoclimatology. So

bang goes that theory.

The background to this is that the BBC recently spent five years

fighting a pensioner named Tony Newbery, including four days in

court with six lawyers, to prevent Mr Newbery seeing the list of 28

participants at a BBC seminar in 2006 of what it called “the best

scientific experts” on climate change.

This was the seminar that persuaded the BBC it should no longer

be balanced in its coverage of climate change. A blogger named

Maurizio Morabito then found the list on the internet anyway. Far

from consisting of the “best scientific experts” it included just

three scientists, the rest being green activists, with a smattering

of Dave Spart types from the church, the government and the

insurance industry. Following that debacle, the BBC

commissioned a report from a geneticist, Steve Jones, which it

revisited in a further report to the BBC Trust last week. The Jones

report justified a policy of banning sceptics under the term “false

balance”. This takes the entirely sensible proposition that

reporters do not have to, say, interview a member of the Flat Earth

Society every time they mention a round-the-world yacht race, and

stretches it to the climate debate.

Which is barmy for two blindingly obvious reasons: first, the

UN’s own climate projections contain a range of outcomes from

harmless to catastrophic, so there is clearly room for debate; and

second, this is an argument about the future not the present, and

you cannot havecertainty about the future.

The BBC bends over backwards to give air time to minority

campaigners on matters such as fracking, genetically modified

crops, and alternative medicine. Biologists who think GM crops are

dangerous, doctors who think homeopathy works and engineers who

think fracking has contaminated aquifers are far rarer than climate

sceptics. Yet Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth spokesmen are

seldom out of Broadcasting House.

So the real reason for the BBC’s double standard becomes clear:

dissent in the direction of more alarm is always encouraged;

dissent in the direction of less alarm is to be suppressed.

I sense that some presenters are growing irritated by their

bosses’ willingness to take orders from the green movement. Others