Matt Ridley's Blog, page 16

March 18, 2018

Good news is gradual, bad news sudden

My Times column on the how pessimism bias affects the way we think:

‘Deadly new epidemic called Disease X could kill millions, scientists warn,” read one headline at the weekend. “WHO issues global alert for potential pandemic,” read another. Apparently frustrated by the way real infectious diseases keep failing to wipe us out, it seems that the nannies at the World Health Organisation have decided to invent a fictitious one.

Disease X is going to be a virus that jumps unexpectedly from an animal species, as happens from time to time, or perhaps a man-made pathogen from a dictator’s biological warfare laboratory. To be alert for such things is sensible, especially after what has happened in Salisbury, but to imply that the risk is high is irresponsible.

No matter how clever gene editors get, the chances that they could beat evolution at its own game and come up with the right combination of infectiousness, lethality and viability to spread a disease through the human race are vanishingly small. To do so in secret would be even harder.

I fear the only effect of the WHO’s decision could be to cause unnecessary alarm and damage public confidence in the very technology that brings more effective cures and vaccines for known and unknown diseases. It also feeds our appetite for bad news rather than good. Almost by definition, bad news is sudden while good news is gradual and therefore less newsworthy. Things blow up, melt down, erupt or crash; there are few good-news equivalents. If a country, a policy or a company starts to do well it soon drops out of the news.

This distorts our view of the world. Two years ago a group of Dutch researchers asked 26,492 people in 24 countries a simple question: over the past 20 years, has the proportion of the world population that lives in extreme poverty

1) Increased by 50 per cent?

2) Increased by 25 per cent?

3) Stayed the same?

4) Decreased by 25 per cent?

5) Decreased by 50 per cent?

Only 1 per cent got the answer right, which was that it had decreased by 50 per cent. The United Nations’ Millennium Development goal of halving global poverty by 2015 was met five years early.

As the late Swedish statistician Hans Rosling pointed out with a similar survey, this suggests people know less about the human world than chimpanzees do, because if you had written those five options on five bananas and thrown them to a chimp, it would have a 20 per cent chance of picking up the right banana. A random guess would do 20 times as well as a human. As the historian of science Daniel Boorstin once put it: “The greatest obstacle to discovery is not ignorance — it is the illusion of knowledge.”

Nobody likes telling you the good news. Poverty and hunger are the business Oxfam is in, but has it shouted the global poverty statistics from the rooftops? Hardly. It has switched its focus to inequality. When The Lancet published a study in 2010 showing global maternal mortality falling, advocates for women’s health tried to pressure it into delaying publication “fearing that good news would detract from the urgency of their cause”, The New York Times reported. The announcement by Nasa in 2016 that plant life is covering more and more of the planet as a result of carbon dioxide emissions was handled like radioactivity by most environmental reporters.

What is more, the bias against good news in the media seems to be getting worse. In 2011 the American academic Kalev Leetaru employed a computer to do “sentiment mining” on certain news outlets over 30 years: counting the number of positive versus negative words. He found “a steady, near linear, march towards negativity”. A recent Harvard study found that 87 per cent of the coverage of the fitness for office of both candidates in the 2016 US presidential election was negative. During the first 100 days of Donald Trump’s presidency, 80 per cent of all coverage was negative. He is of course a master of the art of playing upon people’s pessimism.

This is a human susceptibility and one that is open to exploitation. Even while saying that they would prefer good news, subjects in a subtle psychology experiment in Canada who were told to choose and read a newspaper article while waiting for the “experiment” to begin in fact “chose stories with a negative tone — corruption, setbacks, hypocrisy and so on — rather than neutral or positive stories”. Financial journalists have been found to report rising financial market indices with declining enthusiasm as rises continue, but falling ones with growing enthusiasm as the falls continue. As the Financial Times columnist John Authers said: “We are far more scared of encouraging readers to buy and ushering them into a loss, than we are of urging them to be cautious, and leading them to miss out on a gain.”

That is one reason for the pervasive negativity bias that afflicts the public discourse. Humans are loss-averse, disliking a loss far more than they like an equivalent gain. Such a cognitive bias probably kept us safe amid the dangers of the African savannah, where the downside of taking risks was big. The golden-age tendency makes us remember the good things about the past but forget the bad, with the result that the present seems worse than it is. For some reason people sound wiser if they think things are going to turn out badly. In fiction, Cassandra’s doom-mongering proved prescient; Pollyanna was punished for her optimism by being hit by a car.

Thus, any news coverage of the future is especially prone to doom-mongering. Brexit is a splendid example: because it has not yet happened, all sorts of ways in which it could go wrong can be imagined. The supreme case of unfalsifiable pessimism is climate change. It has the advantage of decades of doom until the jury returns. People who think the science suggests it will not be as bad as all that, or that humanity is likely to mitigate or adapt to it in time, get less airtime and a lot more criticism than people who go beyond the science to exaggerate the potential risks. That lukewarmers have been proved right so far cuts no ice.

Activists sometimes justify the focus on the worst-case scenario as a means of raising consciousness. But while the public may be susceptible to bad news they are not stupid, and boys who cry “wolf!” are eventually ignored. As the journalist John Horgan recently argued in Scientific American: “These days, despair is a bigger problem than optimism.”

March 12, 2018

Britain's housing crisis is caused by the wrong kind of regulation

My Times column on Britain's housing crisis:

Sajid Javid, the Housing (etc) secretary, is right – and brave -- to go on the warpath about Britain’s housing crisis in his new national planning framework, to be launched today. Britain’s housing costs are absurdly high by international standards: eight times average earnings in England, 15 in London. A mortgage deposit that took a few years to earn in the early 1990s can now take somebody decades to earn. Average rents in the UK are almost 50% higher than average rents in Germany, France and crowded Holland.

Britain really is an outlier in this respect. Knightsbridge has overtaken Monaco in rental levels. Wealthy, crowded Switzerland has falling house prices and lower rents than Britain. Over recent decades, most things people buy have become more affordable – food, clothing, communication – and the cost of building a house has come down too. Yet the price you pay for it in Britain, either as a buyer or a tenant, has gone up and up.

Speculation exacerbates the problem. British people, and foreign investors here, borrow money to invest in housing on the generally valid assumption that it will rise in value. This distorts our economy, diverting funds from more productive investments and exacerbating labour shortages in expensive places like London and Cambridge.

The fastest take-off in house prices relative to earnings has been in the last two decades, when cheap money has further fuelled the house-price spiral, rewarding the haves at the expense of the have-nots. The high cost of housing is by far the biggest contributor to inequality. The reason some people have to turn to food banks is not because of high food prices, but because of high housing costs. It is a rich irony that the Attlee government’s town and country planning act of 1947 is probably as responsible as anything for the continuing prosperity of most dukes.

But seeking out profiteers misses the point. At root of the problem is supply and demand. Britain restricts the supply of housing through its planning system far more tightly than other countries. That keeps prices going up, enabling developers, landlords and speculative buyers to make gains. We are building not much more than half as many houses each year as France, despite a faster population growth rate, and a quarter as many as Japan.

So why is British planning so restrictive? Until 1947 Britain regulated house building in most cities the same way other countries did: by telling people what they could build, rather than whether they could build. As Nicholas Boys Smith, director of Create Streets told a recent conference at the Legatum Institute, in the centuries following the Great Fire of 1666, “There was a series of pieces of legislation that set down very tight parameters: ratio of street width to street height, the fire treatment of windows etc. That is how most of Europe still manages planning. They have not taken away your right to build a building.”

Britain switched to deregulating what you could build, but nationalized whether you could build, by adopting a system of government planning, in which permission to build was determined by officials responding to their own estimate of “need”. This brought great uncertainty to the system, because planning permission now depended on the whims of planners, the actions of rivals and the representations of objectors. Today local plans are often years out of date if they exist at all, and are vast, unwieldy documents, opaque to ordinary citizens and subject to endless legal challenge and revision.

This makes Britain both far more subject to centralized command and control and far more dominated by big corporations than other countries. It is a good example of how socialism and crony capitalism go hand in hand. Barriers to entry erected by planning play into the hands of large companies and make it hard for small, innovative competitors to take them on. In turn, this leads developers to produce unimaginative, repetitive designs to get the best return on their huge investment in land and permission.

Getting planning permission to build houses in Britain requires you to spend big sums on consultants, lawyers, lobbyists and public relations experts, as you wear down the councils’ planning teams and their ever growing lists of questions over several years. Not that the two sides to such debates are really antagonists: it is more like a symbiosis, a dance in which both sides benefit, because the fees to be earned by everybody from ecologists to economists are rich. And that is because at the end of the process the reward can be huge: a 100-fold uplift or more in the value of a field that gets turned into housing.

As a property owner, I have experience of this system and, I freely admit, a vested interest in it. I should be arguing for it, rather than against. However frustrating planning authorities can be, the rewards they bring to property owners can be large, either through upward pressure on prices and rents by their restrictions on permissions, or through uplifts in the value of land zoned for development.

Our mostly centralised taxes make things worse. In Switzerland, cantons compete for the local taxes that residential property owners pay, encouraging them to agree promptly to building bids, whereas here development brings headaches for local councils in providing infrastructure and services, only partly redressed with “section 106” agreements that make developers pay for schools and roads.

The system also creates opportunities for nimbyism on a greater scale than elsewhere. Opposing new development because it blocks your view, increases congestion on the roads and crowds the doctor’s surgery and local school, is rational everywhere. But it is much easier to organize a protest when the decisions are taken by council officials and the permissions are for big projects, rather than where many small decisions to build are taken by many dispersed owners and builders.

If Sajid Javid is to succeed in revolutionizing Britain’s housing market, he must tackle the underlying causes. Rent control, help-to-buy, affordable housing mandates and bearing down on developers’ land banks mostly address the symptoms. Forcing councils to set higher targets for house building is a start, but if he were to succeed in unleashing a building boom across the country sufficient to bring down house prices he would create a debt crisis among those with negative equity. So it will not be easy to cure Britain’s addiction to property, but he must try.

February 28, 2018

Labour is now for the few, not the many

My Times column on the liberal case against the protectionism in the EU customs union:

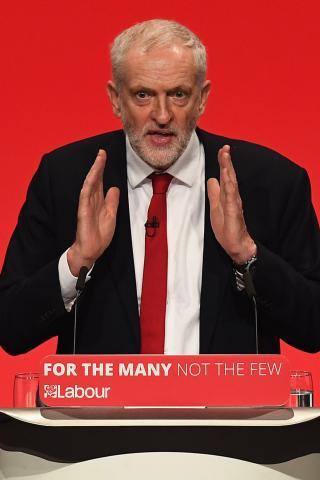

If reports are accurate, there is at least one thing in Jeremy Corbyn’s speech today with which I will agree: “The EU is not the root of all our problems and leaving it will not solve all our problems. Likewise the EU is not the source of all enlightenment and leaving it does not inevitably spell doom for our country. Brexit is what we make of it together.” Yet this makes his overall conclusion, that we should stay in “a” customs union with the European Union, all the more baffling. That would be the worst of all worlds. It would be, in an inversion of the Labour Party’s phrase, “for the few, not the many”.

Mr Corbyn’s proposed customs union would benefit the few, not the manyLEON NEAL/GETTY IMAGES

As Steven Pinker sets out in his new book Enlightenment Now, human beings are cursed by a pervasive negativity bias, “driven by a morbid interest in what can go wrong”. Yet again and again, we defy the pessimists and improve the world. Brexit is fertile ground for this proclivity for pessimism because it has not yet happened. Our imaginations, and those of people with political axes to grind, run riot.

This is being exploited by the paid servants of big business and big government to try to keep us in a customs union system that benefits both. Ordinary people, in my experience, mostly see through this, as they did on referendum day. As a report from the organisations Labour Leave, Economists for Free Trade and Leave Means Leave calculated, the poor would benefit most from Brexit. If the Labour Party is really on the side of the poor rather than the elite, the EU customs union is a curious thing to defend. As David Paton, the professor of industrial economics at Nottingham University Business School, pointed out in a recent paper, The Left-wing Case for Free Trade, free trade always used to be a left-wing cause.

Free trade says to the poorest: we will enable you to get access to the cheapest and best products and services from wherever in the world they come. We will not, in the economist Joan Robinson’s arresting image, put rocks in our own harbours to obstruct arriving cargo ships just because other people put rocks in theirs. The customs union, however, says: if Italy wants rocks in its harbours to protect its rice growers against Asian competition, then Britain must have them too, even though it grows no rice.

Take trainers. Britain makes very few such shoes. It imports lots. The average external EU customs union tariff on them is 17 per cent. Four fifths of this money goes straight to the European Commission. Poor people do not necessarily buy more trainers than rich people but trainers are a higher percentage of their spending. Their inflated trainer prices mean they spend less on other things, which hurts other producers, many of them British, affecting jobs and pay. The tariffs are there for pure protectionism: to aid the shoe industry elsewhere in Europe.

The purpose of all production is consumption, said Adam Smith. Or, as the American wit PJ O’Rourke put it, “imports are Christmas morning; exports are January’s Mastercard bill”. Yet the conversation about the customs union has been conducted almost entirely on behalf of producers, and exporters in particular. Remember, according to the Office for National Statistics in 2016, trade with the EU accounts for only 12 per cent of gross domestic product. It is not unreasonable to put the interests of the other 88 per cent first.

The poor are consumers too. So are businesses, including ones that export. They import raw materials and other goods and the cheaper those are, the more competitive our exporters will be. Outside a customs union, we would not have to cut all tariffs. If we wanted to protect certain British industries then we could, although I hope we would do so sparingly and temporarily.

This argument for free trade is not just a theoretical one. It was demonstrated unambiguously when we flourished after repealing the Corn Laws, which also privileged producers at the expense of consumers, in the mid-19th century. It was demonstrated by the two most free-trading economies in the world, Singapore and Hong Kong, as they roared past us in the prosperity league table from very poor to very rich in recent decades, and more recently by New Zealand and Australia, fast-growing since their turns towards freer trade.

The customs union diverts our trade towards Europe at the expense of poorer countries. The customs union is not a free trade area. It would be possible to be in a free trade area with the EU while outside a customs union, like Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein.

That we voted to leave the customs union should not be in doubt. The Vote Leave organisation made clear that “Britain lacks the power to strike free trade deals with its trading partners outside Europe. Being in the EU means that Brussels has full control of our trade policy . . . if we vote Leave, we can negotiate for ourselves.” The government made clear that “a common external trade policy is an inherent and inseparable part of a customs union” and that apart from emulating Turkey’s subservient relationship with the EU, “all the alternatives involve leaving the customs union”.

In 1846, two years before the publication of The Communist Manifesto, Richard Cobden, the campaigning manufacturer and politician whose rational optimism has proved a better guide to subsequent history than the conflict-obsessed dialectic of Karl Marx, made a speech in Manchester. “I believe that the physical gain will be the smallest gain to humanity from the success of this principle [free trade],” he said. “I look farther; I see in the free trade principle that which shall act on the moral world as the principle of gravitation in the universe — drawing men together, thrusting aside the antagonism of race, and creed, and language, and uniting us in the bonds of eternal peace.

“I have looked even farther . . . I believe that the desire and the motive for large and mighty empires; for gigantic armies and great navies — for those materials which are used for the destruction of life and the desolation of the rewards of labour — will die away; I believe that such things will cease to be necessary, or to be used, when man becomes one family, and freely exchanges the fruits of his labour with his brother man.”

Give it a try, Jeremy.

February 24, 2018

The Russian role in the nuclear winter theory

My Times column on the Russian encouragement and perhaps origin of the now discredited theory of "nuclear winter":

So, Russia does appear to interfere in western politics. The FBI has charged 13 Russians with trying to influence the last American presidential election, including the whimsical detail that one of them was to build a cage to hold an actor in prison clothes pretending to be Hillary Clinton.

Meanwhile, it emerges that the Czech secret service, under KGB direction, near the end of the Cold War had a codename (“COB”) for a Labour MP they had met and hoped to influence — presumably under the bizarre delusion that he might one day be in reach of power.

There is no evidence that Jeremy Corbyn was a spy, or of collusion by Trump campaign operatives with the Russians who are charged. Yet the alleged Russian operation in America was anti-Clinton and pro-Trump. It was also pro-Bernie Sanders and pro-Jill Stein, the Green candidate — who shares with Vladimir Putin a

strong dislike of fracking.

The Keystone Cops aspects of these stories should not reassure. The interference by Russian agents in western politics during the Cold War was real and dangerous. A startling example from the history of science has recently been discussed in an important book about the origins of the environmental movement, Green Tyranny by Rupert Darwall.

In June 1982, the same month as demonstrations against the Nato build-up of cruise and Pershing missiles reached fever pitch in the West, a paper appeared in AMBIO, a journal of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, authored by the Dutchman Paul Crutzen and the American John Birks. Crutzen would later share a Nobel prize for work on the ozone layer. The 1982 paper, entitled The Atmosphere after a Nuclear War: Twilight at Noon, argued that, should there be an exchange of nuclear weapons between Nato and the Soviet Union, forests and oil fields would ignite and the smoke of vast fires would cause bitter cold and mass famine: “The screening of sunlight by the fire-produced aerosol over extended periods during the growing season would eliminate much of the food production in the Northern Hemisphere.”

Alerted by environmental groups to the paper, Carl Sagan, astronomer turned television star, then convened a conference on the “nuclear winter” hypothesis in October 1983, supported by leading environmental and anti-war pressure groups from Friends of the Earth to the Audubon Society, Planned Parenthood to the Union of Concerned Scientists. Curiously, three Soviet officials joined the conference’s board and a satellite link from the Kremlin was provided.

In December 1983, two papers appeared in the prestigious journal Science, one on the physics that became known as TTAPS after the surnames of its authors, S being for Sagan; the other on the biology, whose authors included the famous biologists Paul Ehrlich and Stephen Jay Gould as well as Sagan. The conclusion of the second paper was extreme: “Global environmental changes sufficient to cause the extinction of a major fraction of the plant and animal species on Earth are likely. In that event, the possibility of the extinction of Homo sapiens cannot be excluded.”

Who started the scare and why? One possibility is that it was fake news from the beginning. When the high-ranking Russian spy Sergei Tretyakov defected in 2000, he said that the KGB was especially proud of the fact “it created the myth of nuclear winter”. He based this on what colleagues told him and on research he did at the Red Banner Institute, the Russian spy school.

The Kremlin was certainly spooked by Nato’s threat to deploy medium-range nuclear missiles in Europe if the Warsaw Pact refused to limit its deployment of such missiles. In Darwall’s version, based on Tretyakov, Yuri Andropov, head of the KGB, “ordered the Soviet Academy of Sciences to produce a doomsday report to incite more demonstrations in West Germany”. They applied some older work by a scientist named Kirill Kondratyev on the cooling effect of dust storms in the Karakum Desert to the impact of a nuclear exchange in Germany.

Tretyakov said: “I was told the Soviet scientists knew this theory was completely ridiculous. There were no legitimate facts to support it. But it was exactly what Andropov needed to cause terror in the West.” Andropov then supposedly ordered it to be fed to contacts in the western peace and green movement.

It certainly helped Soviet propaganda. From the Pope to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament to the non-aligned nations, calls for Nato’s nuclear strategy to be rethought because of the nuclear winter theory came thick and fast. A Russian newspaper used the nuclear winter to inveigh against “inhuman aspirations of the US imperialists, who are pushing the world towards nuclear catastrophe”. In his acceptance speech of the Nobel peace prize in 1985, the prominent Russian doctor Evgeny Chazov cited the Nobel committee's citation: "a considerable service to mankind by spreading authoritative information and by creating an awareness of the catastrophic consequences of atomic warfare". The statement continued: "...this, in turn, contributes to an increase in the pressure of public opposition".

“Propagators of the nuclear winter thus acted as dupes in a disinformation exercise scripted by the KGB”, concludes Darwall. We can never be entirely certain of this because Tretyakov’s KGB colleagues may have been exaggerating their role and he is now dead. But that the KGB did its best to fan the flames is not in doubt.

It soon became apparent that the nuclear winter hypothesis was plain wrong. As the geophysicist Russell Seitz pointed out, “soot in the TTAPS simulation is not up there as an observed consequence of nuclear explosions but because the authors told a programmer to put it there”. He added: “The model dealt with such complications as geography, winds, sunrise, sunset and patchy clouds in a stunningly elegant manner — they were ignored.” The physicist Steven Schneider concluded that “the global apocalyptic conclusions of the initial nuclear winter hypothesis can now be relegated to a vanishingly low level of probability”.

The physicists Freeman Dyson and Fred Singer, who would end up on the opposite side of the global-warming debate from Schneider and Seitz, calculated that any effects would be patchy and short-lived, and that while dry soot could generate cooling, any kind of dampness risked turning a nuclear smog into a warming factor and a short-lived one at that.

By 1986 the theory was effectively dead, and so it has remained. A nuclear war would have devastating consequences, but the impact on the climate would be the least of our worries.

The stakes were higher in the Cold War than today. The Soviet peace offensive secured the support of many western intellectuals and much of the media, and very nearly prevailed.

February 18, 2018

Shale is the real energy revolution

My Times thunderer column on shale gas and shale oil and Britain's opportunity:

Gas will start flowing from Cuadrilla’s two shale exploration wells in Lancashire this year. Preliminary analysis of the site is “very encouraging”, bearing out the British Geological Survey’s analysis that the Bowland Shale beneath northern England holds one of the richest gas resources known: a huge store of energy at a cost well below that of renewables and nuclear.

A glance across the Atlantic shows what could be in store for Britain, and what we have missed out on so far because of obstacles put in place by mendacious pressure groups and timid bureaucrats. Thanks to shale, America last week surpassed the oil production record it set in 1970, having doubled its output in seven years, while also turning gas import terminals into export terminals.

The effect of the shale revolution has been seismic. Cheap energy has brought industry back to America yet carbon dioxide emissions have been slashed far faster than in Europe as lower-carbon gas displaces high-carbon coal. Environmental problems have, contrary to the propaganda, been minimal.

All thoughts of imminent peak oil and peak gas have vanished. Opec’s cartel has been broken, after it failed to kill the shale industry by driving the oil price lower: American shale producers cut costs faster than anybody thought possible. A limit has been put on the economic and political power of both Russia and Saudi Arabia, no bad thing for the people of both countries and their neighbours. Shale drillers turn gas and oil production on and off in response to price fluctuations more flexibly than old-fashioned wells.

Seven years ago it was possible to argue that shale would prove a flash in the pan. No longer: horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing are the biggest energy news of the century. For those who still think the falling price of wind and solar is more dramatic, consider this. Between them, those two energy sources provided just 0.8 per cent of the world’s energy in 2016, even after trillions of dollars in subsidy, and will reach only 3.6 per cent by 2040, according to the International Energy Agency. Gas will then be providing 25 per cent of the world’s energy, up from 22 per cent today.

Gas is one of the cheapest, safest, least polluting, most reliable and flexible of energy sources, and it does not require subsidy or huge areas of land like renewables. Britain once had a great abundance thanks to the North Sea but that is dwindling. Shale resources would almost certainly have come forward to fill that gap, but by letting the renewables lobby and green pressure groups rig the market against gas, the government is letting slip a historic opportunity.

February 13, 2018

Censorious millennials are the new Victorians

My Times column on how the censorious and prudish young are a bit like Victorians:

I am sure I am not alone in finding the cultural revolution that we are going through difficult to understand. Like a free-living Regency rationalist who has survived to see Victorian prudery, like a moderate critic of Charles I trying to make sense of the Cromwellian dogma, like a once revolutionary Chinese democrat hoping not to be denounced and sent for re-education under Chairman Mao (or John McDonnell), I am an easygoing Seventies libertarian baffled by the aggressive puritanism and intolerance that seems to be everywhere on the march.

I turned 60 last week and expected by now to find myself in periodic, grumpy disapproval of the younger generation’s scorn for tradition, love of change and tolerance of “anything goes”. Instead I find something approaching the opposite. Many people of my generation have mentioned the same experience recently: the terrifying censoriousness of the young, even sometimes their own children, and the eggshell-treading dread of saying the wrong thing in front of them. The young are a bit like our parents were, in fact.

What happened to the liberation of the Sixties and Seventies, when you could start to forget hierarchy and say just about anything to and about anybody? Pictures of young women in make-up, short skirts and high heels walking down the street in Kabul or Tehran in the Seventies are in shocking contrast with the battle that modern Iranian women, dressed mostly in all-concealing black, are bravely fighting to gain the right to remove a headscarf without being arrested.

Is it so different here or are we slipping down the same slope? Pre-Raphaelite paintings that show the top halves of female nudes are temporarily removed from an art gallery’s walls; young girls are forced to wear headscarves in school; darts players and racing drivers may not be accompanied by women in short skirts; women are treated differently from men at universities, as if they were the weaker sex, and saved from seeing upsetting paragraphs in novels; sex is negotiated in advance with the help of chaperones. We have been here before.

In Orlando, Virginia Woolf’s novel of 1928, she portrayed the transition from the 18th century to the Victorian period thus: “Love, birth, and death were all swaddled in a variety of fine phrases. The sexes drew further and further apart. No open conversation was tolerated. Evasions and concealments were sedulously practised on both sides.”

How we laughed at such absurdity in my youth. But even for making the point that some of the new feminism seems “retrograde” in promoting the view that women are fragile, the American academic Katie Roiphe suffered a vicious campaign to have her article in Harper’s magazine banned before publication. “I find the Stalinist tenor of this conversation shocking,” she told The Sunday Times. “The basic assumption of freedom of speech is imperilled in our culture right now.”

The sin of blasphemy is back. There are things you simply cannot say about Islam and increasingly about Christianity, about climate change, about gender, to mention a few from a very long and growing list, without being accused of, and possibly prosecuted for, “hate speech”. Is it hate speech to say that Muhammad “delivers his country to iron and flame; that he cuts the throats of fathers and kidnaps daughters; that he gives to the defeated the choice of his religion or death: this is assuredly nothing any man can excuse”? That was Voltaire, one of my heroes. You may disagree with him but you should, in accordance with his principle, defend his right to say it. In demanding tolerance of minorities, many younger people seem to be remarkably intolerant.

There is an odd contradiction between the declared wish to live and let live — “diversity!”, “don’t judge!” — and the actual behaviour, which is ruthlessly and priggishly judgmental. They never stop drafting acts of uniformity, always in the name of the collective against the individual. The minority of one is the most oppressed minority of all.

Perhaps, being a meat-eating, heterosexual, titled, atheist, climate-sceptic male who thinks communism was evil, gender is partly biological, genetically modified crops are good for the environment, free markets make people nicer and that Britain should leave the European Union, it is just me who finds himself perpetually on the politically incorrect side of arguments, or at least the opposite side from the BBC. But it does feel as though almost everybody, whatever their views, is one step away from public denunciation.

We need a morality, of course, and one that does more to challenge bad behaviour whether in Hollywood or Oxfam, but that does not require being more puritan about speech and thought. I have often wondered how it was that in the past societies suddenly became more censorious, conservative and intolerant, as they did at the start of the Victorian era, but I thought that I was living in a time when none of that could happen, when culture was on a one-way escalator towards liberality.

In the Sixties Francis Crick held a contest for what to do with the college chapels in Cambridge, because in the future nobody would be religious. Imagine that. Of course, we knew what was going on in China — the Cultural Revolution was a political purge dressed up as moral rearmament — but we shuddered at the alien nature of such a thing. Now it seems closer.

The thugs who recently tried to prevent Jacob Rees-Mogg speaking at a university are now a familiar routine on campus. But, as the American journalist Andrew Sullivan warns, the campus is a harbinger for the whole of society: “Workplace codes today read like campus speech codes of a few years ago . . . the goal of our culture now is not the emancipation of the individual from the group, but the permanent definition of the individual by the group. We used to call this bigotry. Now we call it being woke. You see: we are all on campus now.”

Nevertheless, I remain a rational optimist. Like the psychologist Steven Pinker in his new book, I think “the Enlightenment is working”, still. Reason can prevail over dogma, science over superstition, freedom over tyranny, individualism over apartheid. Progress is not dead. Yet. But we have certainly taken a few steps backward towards a darker way of running society. Why? I still don’t have an answer.

February 7, 2018

Civil servants have views too

My Times column on the impartiality of public servants:

Last week saw political eruptions on either side of the Atlantic about a similar issue: whether government officials are neutral. The row over the leaked forecasts for Brexit, and whether civil servants were being partisan in preparing and perhaps leaking them, paralleled the row in America about the declassified Congressional memo on the FBI and Donald Trump. “Trump’s unparalleled war on a pillar of society: law enforcement”, said TheNew York Times. “Brexit attacks on civil service ‘are worthy of 1930s Germany’ ” said The Observer.

To summarise, in London a government forecast that even a soft Brexit would be slightly worse for the economy than non-Brexit was conveniently leaked. This happened just as some politicians and commentators were trying to shift the country towards accepting a form of customs union with the European Union — that is to say, not really leaving at all.

In Washington, the president declassified a memo prepared by Devin Nunes, the chairman of the House intelligence committee. It alleged that the FBI got a warrant from a secret court to bug a Trump campaign executive, using as evidence mainly a “salacious and unverified” dossier (the former FBI director James Comey’s words) prepared by a British ex-spy paid by the Democratic Party, a fact that the FBI apparently failed on three occasions to tell the court. The FBI also allegedly leaked the dodgy dossier to the press.

There are two sides to both stories. In Washington, the Democrats and some Republicans see a president prepared to break secrecy to make the FBI look bad, presumably as a distraction from its investigation of his alleged links with Russia. In London, Remainers focus on the fact that it is unusual and wrong for politicians to attack civil servants who are not allowed to answer back.

Nobody disputes, surely, that civil servants have views. Since 91 per cent of Washington DC voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016, and a similar percentage of public servants here probably voted Remain, we can guess what those views are in most cases. Former mandarins in the House of Lords and on Twitter are among the most outspoken opponents of Brexit in any form. In the FBI case, several key people (including the British

ex-spy, Christopher Steele) are on record as having been passionately opposed to Mr Trump’s election.

But civil servants are public employees and should do the bidding of the elected politicians who represent their employers. When they helped to prepare a flimsy dossier to justify the invasion of Iraq in 2003, making claims about weapons of mass destruction that proved wrong, civil servants were not freelancing but responding to political pressure. The error was political. The civil service did its job.

As chancellor, George Osborne set up the Office of Budget Responsibility precisely to remove economic forecasting from political pressure. Yet the Treasury returned to economic forecasting during the referendum campaign. It said that “a vote to leave would represent an immediate and profound shock to our economy. That shock would push our economy into a recession and lead to an increase in unemployment of around 500,000, GDP would be 3.6 per cent smaller” and so on. This turned out to be based on ridiculous assumptions and was utterly discredited by what actually happened.

This case is different, however. By all accounts the Treasury was stung by the humiliating failure of Project Fear (which would never have been exposed if Remain had won the referendum, remember). This latest forecast is not from a Treasury model at all but a “cross-departmental tool”, as Amber Rudd said yesterday. Nor is it based on the discredited “gravity” assumption, that trade decreases with the square of distance. It is thought to be a “computable general equilibrium model” of the kind that the Treasury’s critics have long recommended.

It is not clear who developed the model. It might have been contracted from an outside consultant. There is no evidence it has been “back-tested” on the British economy’s past performance to see if it works. More problematically still, the model does not test the government’s preferred policy at all, and makes ludicrous assumptions about what would happen under its three scenarios.

For example, if we leave on World Trade Organisation terms, it assumes we would keep the external tariffs of the EU that inflate the household costs of British consumers. Given that trade with the EU is about 12 per cent of British GDP, in order to achieve an 8 per cent hit to GDP, the model has to assume we would lose at least half that trade, which is for the birds. Garbage in, garbage out, as they say in modelling.

Who commissioned the forecasts? It appears it was not Treasury officials but nor was it a politician. The relevant ministers have distanced themselves. It looks increasingly like a freelance operation from within the top layers of the civil service. If so, this might indeed justify criticism not so much for doing analysis, but in who they got to model it. Being culturally averse to Brexit and free markets, they just would not think of going to economists like Roger Bootle, Gerard Lyons, Ryan Bourne, Liam Halligan and Patrick Minford, who see opportunities in leaving. They do not even realise they are being biased.

The pass-the-smelling-salts shock of those leaping to the defence of civil servants is excessive, as was their comparison of the critics to Hitler and snake-oil salesmen. Civil servants get secure, well-paid jobs with early retirement and excellent pensions. And when they screw up, politicians generally carry the can for them. An occasional question from a politician about whether they are letting their prejudices get in the way of doing their job may be uncomfortable, but it’s hardly unreasonable.

If they mount a freelance operation that frustrates a democratic mandate then all bets should be off, just as if it emerges that the FBI was freelancing to undermine a presidential candidate (either of them), then it would be a major scandal.

Britain faces its greatest decision in decades. If we leave the customs union, keep its tariffs and do nothing else, of course there will be pain. But if we also open up our economy more to the growing markets of Asia, Africa, Australasia and the Americas, and take measures to encourage investment and innovation, we will blow away any pessimistic forecasts. Civil servants should be modelling those possibilities.

February 3, 2018

Future divergence is the point of leaving the European Union

My Times column on Britain's opportunity to diverge from the EU:

At the risk of infuriating both sides in the parliamentary civil war over Brexit, I humbly suggest a compromise. The central issue is divergence: how much should Britain aim to veer away from the Continent in how it regulates products and services, and how much would the 27 countries and the European Commission allow us to diverge before denying us a trade deal at all?

Between the hope of Philip Hammond, the chancellor, for “very modest” divergence and Jacob Rees-Mogg’s fear that this would leave us a “vassal state”, there is a gulf. Yet (like the English Channel) it may not be unbridgeable. Part of the compromise would be for Britain to start out in close alignment on existing products and services, but to be free to diverge not by repealing existing laws, but as new technologies and conundrums arise.

David Davis, the Brexit secretary, hinted at such a thing last week. There is never much appetite for wholesale repeal of regulation. It is all too easy for opponents to portray it as a dangerous betrayal of the safety of the public, even if this is not the case.

Besides, repeal is surprisingly unpopular with a sector groaning under the burden of a regulation, however much that sector protested when the regulation first came in. By the time the financial sector has adopted and adapted to some heavy-handed rule on money laundering that (let’s imagine) requires the inside-leg measurements of clients to be rechecked every six months by an independent tailor, it will have geared up to meet the rule. It quite enjoys the barrier to entry. Insurgent competitors struggle to find tailors who are not already signed up.

The tailors now have a lucrative new business line and will lobby hard for keeping the regulation in place, by leaking to the media blood-curdling stories of frauds that could be perpetrated were inside-leg measurements not taken. This is the reality of regulation, its dirty little secret: it always benefits incumbents by raising hurdles to new entrants, and it creates vested interests. Even the most egregious rules, ones that clearly get in the way of offering better value to customers while doing nothing to protect them, prove almost impossible to repeal.

So there is, in practice, going to be no appetite for a bonfire of EU regulations on the day that we leave the EU, much as I would like there to be. I would tear up the counterproductive rules on newt protection, biotech crops and vaping, and the ban on the life-saving Swedish tobacco substitute snus for a start, but I am unlikely to find sufficient support. A few symbolic abolitions of rules that do not matter much are the best we can hope for.

Incidentally, America may be about to prove me wrong, but I doubt it. I am told by American friends that while the media is distracted by the chaos and confusion in the White House, the lower echelons of the Trump administration are pushing ahead with wholesale deregulation and decluttering of bureaucracy.

As an example, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), normally keen to ban things, last week challenged Columbia University to give it the data from a study that was used to justify a lawsuit forcing the banning of a pesticide. The agency’s words were: “Despite multiple requests, an EPA visit to Columbia, and a public commitment to ‘share all data gathered,’ [the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health] has not provided EPA with the data used.”

However, I suspect the greatest deregulatory impact of the Trump administration will come much later, when the new judges it has appointed start resisting calls for new regulations. It is in the nature of modern society that regulators constantly face new challenges to which they must respond.

It is here that divergence really matters. After leaving the EU Britain will face new technologies and habits for which it will require new rules. So long as we are free to promulgate such rules in different ways from our “close and special” partners across the Channel, without their being struck down by the European Court of Justice, then we need not be a vassal state.

Let me give a real example. The growing potential of artificial intelligence (AI) is throwing up new challenges in the use of data, in the legal liability of machines and so forth. At present the general view in this country, and in most countries, is that a special AI regulator would be a mistake, that existing bureaucracies can cope with the issue and that we mainly face new versions of old problems. As time goes by, this may need to change.

Ten years from now both the EU and the UK may have begun bringing in new AI-specific rules. It is unlikely these would need to be identical, even if they aimed to achieve a similar result. Ours might more reflect the importance of financial services to the British economy, or the dominant position of the National Health Service in gathering health data.

Twenty years ago nobody could envisage the need for rules for self-driving cars, or gene-edited plants, or fracking, or revenge porn, or chatbots, or biomass power stations. To take a more trivial example in the news, who could have foreseen the sudden resurgence of phone boxes on high streets, driven entirely, it seems, by the opportunity they represent for advertising and the fact they are exempt from planning permission: a loophole that needs addressing?

Just as innovation will lead to a constant stream of new regulations, giving opportunities for Britain and the EU to diverge, so old regulations often eventually become irrelevant thanks to innovation. It is instructive to browse a list of parliamentary acts from the 1930s and see how many no longer matter: from the Hairdressers’ and Barbers’ Shops (Sunday Closing) Act to the Wheat Act.

In short, I am arguing that the big prize is future differentiation, allowing Britain gradually to become a country that aims for similar outcomes as the EU in regulating innovations, but by different methods, ones that (I hope) do less to stifle innovation and competition. This means there might be neither an immediate Brexit pain nor an immediate Brexit dividend. So long as the European Court of Justice cannot strike down our rules, then the future could be a happy one for both sides.

January 22, 2018

The green plan should use human ingenuity

My Times column on the government's 25-year plan for the environment:

The government’s 25-year environment plan is more than a piece of virtue signalling, despite its chief purpose being to persuade the young to vote Conservati(ve)onist. It is full of sensible, apolitical goals and in places actually conveys a love of the natural world, which is not always the case with such documents.

The difficulty will be putting its ambitions into practice. It is all very well to want cleaner air and water, more biodiversity, less plastic litter and richer soils. How are these to be achieved? Except in a few places, such as the discussion of “net environmental gains” in the construction industry, the plan is worryingly vague.

The word that bothers me most, appearing often, is “we”. “The actions we will take . . . we will protect ancient woodland . . . we will increase tree planting” and so on. Who is we? This is the language of the central planner, who assumes that the government decrees and the passive population obeys. There is relatively little sense here that the vast majority of our environment is managed by people or organisations other than the government and that the vast majority of actions that damage or improve it are taken by people other than civil servants.

People do not foul their own nests, on the whole, so the role of government is to create as much sense of real environmental ownership as possible. If the de facto owner of the environment is the state, through too many rules and restrictions, then people will not volunteer to help. Communised assets lack a sense of ownership: look at the litter in laybys, for example, or the terrible state of the environment in Soviet Russia under the state planning committee, or Gosplan.

At the micro level it’s easy to create sense of ownership. Private property is a powerful motivator. At communal levels it’s harder, but not impossible. There are many local conservation charities and private organisations looking after a woodland and a flower meadow here, a stretch of river there: small groups of people who take pride in the responsibility.

One of the critical things Conservatives can bring to the environmental debate, that would not occur to Labour, is surely the idea of decentralised experimentation. The whole point of individual choice is that the commissar cannot know enough to know best, however clever he is.

Now, you cannot always use a commercial market in environmental matters, because people do not willingly pay for the things they want (though sometimes they do — most winter bird seed crops are planted by shooters). But you can at least try different things in different places to learn what works.

The big green pressure groups forget all this. They are more comfortable with a centralised and top-down policy, amenable to lobbying. The reaction of the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) to Michael Gove’s plan is telling: “But these commitments will only become a reality if they are backed by the force of law, money and a new environmental watchdog.” In other words, a green Gosplan, a Goveplan, which would be counterproductive for the same reasons that Gosplan didn’t work.

Take the agri-environment schemes under which farmers are rewarded for doing things that, say, make yellowhammers happy. Most agree, and this plan notes this, that under the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) the schemes have been wasteful, spending fortunes on things that work poorly and too little on things that work well. Talk to smaller research organisations such as the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust and you will find that they have learnt through experimentation how to stop yellowhammers starving at the end of the winter (non-dehiscent plants that don’t shed all their seeds too early). It is the same with wild flowers, woodland and clean water. Good practice spreads by word of mouth in the countryside after practical people discover it through trial and error. The rewilding of the Knepp estate in West Sussex by Sir Charles Burrell, for example, has shown that nightingales are attracted to breed in unkempt thorn hedges.

In the inflexible world of the CAP, with its pillars and schemes and schedules, experimentation is impossible. To the extent that the vagueness of Mr Gove’s plan is a tacit recognition that government’s job should not be to tell people what to do, but to encourage a thousand metaphorical (and literal) flowers to bloom, good. To the extent that it sets out an agenda for the pressure groups and corporatist quangos to colonise with their tick-box mentality, bad. We will have to see which turns out to be true.

In this respect, another welcome feature of the plan is the focus on local environmental goals: plastic, clean water, clean air, soil, wildlife, trees. The big global issues that have dominated the professional environmental industry for so long — global population, resources, acid rain, ozone, climate change — are in the document, but no longer crowding out the local ones as they did for years, and in many cases actively making things worse.

There are still problems. The plan mentions in one breath both climate change mitigation and the prevention of international deforestation, yet fails to spot that the burning of wood for “renewable” electricity and the cultivation of palm-oil biodiesel plantations have been inspired and justified entirely by misguided climate policies. Wind farms do kill birds, as well as trashing landscapes; hydro on free-flowing rivers does harm fish, and so on. Environmental objectives do conflict but the plan shows little recognition of this. The main omission, however, is science. There is no sense in the plan of the technologies becoming available to protect the environment: the biotechnology that has already made agriculture so much greener elsewhere in the world and is limiting land-take; the gene editing that promises to enable us to grow better crops with fewer chemicals; the British breakthroughs that promise to give us contraceptive vaccines to control invasive species humanely; the new techniques for eradicating rats from oceanic islands to save seabirds.

The good intentions of Mr Gove’s plan are obvious and welcome, but they could have been written down any time in the past century, while the means hinted at are regrettably tinged with an anti-scientific and potentially authoritarian puritanism that just won’t work. Five out of ten.

New diagnostic devices will save lives and money

My Times column on the revolution in protein and DNA diagnosis:

As happens in the media, the excitement generated last week by the headline that cancer could be detected in the blood was overdone. The results announced in Science magazine are a long way short of meaning that the earliest signs of cancer can be detected in people with no symptoms: the 70% success rate in finding DNA from 16 cancerous genes was in people already diagnosed with serious cancers. False hopes may have been raised.

But behind the headline, there is little doubt that a revolution in diagnostics is happening. Till now, the slow process of culturing infectious agents to identify them has not changed much since the days of Louis Pasteur. It is becoming increasingly possible to identify the precise virus, bacterium, drug-resistant strain, antibody or telltale molecule that defines exactly what is wrong with somebody, quickly and without invasive procedures or lengthy cultures in distant labs. Yet Britain is lagging behind comparable countries in joining that revolution.

Proteins, fatty acids or DNA sequences, even if present in minuscule concentrations, can now be picked out by new techniques that combine biochemistry and electronics in ever more ingenious ways. Clever algorithms analysing multiple molecular tests promise even more precision. (Disclosure: I am an early-stage investor in a start-up working in the DNA diagnostics field.)

The day when somebody visiting a rural clinic in Africa, or an urban GP’s surgery in London, can be told within minutes – rather than days -- that they have latent tuberculosis, and whether or not it is drug resistant, will soon be on us, even if there are vanishingly few bacterial cells in the sample. The day when somebody can be told whether they have the genetic combination that makes them react poorly to warfarin or some other drug is coming fast, too. The earlier detection of cancer through non-invasive blood tests is also coming a bit more slowly. Early treatment of cancer not only saves lives; it saves money too. Stage 1 treatment for most cancers is one-third to one-quarter as costly as stage 4.

In other words, guessing at a diagnosis based on symptoms, or relying on distant laboratories, is being replaced with simple, sometimes hand-held devices in the clinic. For some hypochondriacs, this will be a moment of vindication. (“I told you I was ill” is the epitaph engraved on Spike Milligan’s headstone in Winchelsea.) For others, it will be a moment of humiliation. Quite a few of those who claim to have Lyme disease, or gluten intolerance, are imagining it and need to be told so. The quacks and alternative practitioners who foment their worries and plunder their wallets deserve to be put out of business by new diagnostic tests.

The counterproductive practice of prescribing antibiotics for colds, against which they are wholly ineffective, should also end. In passing, I remain surprised by how little impact the germ theory of disease has made on ordinary people’s thinking in the 170 years since John Snow first railed against the reigning obsession with blaming cholera on air pollution. To this day I meet hordes of people who insist that their colds were mainly caused by getting wet, or getting run down, or being unhappy, rather than by shaking hands with somebody who carried a virus.

There is a problem for Britain in this diagnostic revolution. For mainly historical reasons, the National Health Service can sometimes be profligate in the way it treats diseases, giving in too readily to the blandishments of drug companies with very slightly better, but much more expensive, versions of a treatment. But it is the opposite with diagnostics. The NHS is notoriously resistant to ordering “tests”, and is exceedingly parsimonious when it comes to buying new blood-diagnostic tools.

The statistics bear this out. The size of the in-vitro diagnostics market in Britain per head of population (not counting infrastructure) is less than half that of Germany and Italy, and about the same as Slovakia and Croatia. This, says the British In Vitro Diagnostics association, is partly because “the benefits of diagnostics are often either misunderstood, or worse, not considered at all” and “the NHS is too inflexible when it comes to adopting new IVD tests. Typically, solutions are still thought of as pharmaceuticals and consideration is not given to how IVDs could be adopted in the system to improve outcomes”.

For example, the leaders of the Northern Irish company, Randox, a pioneer in blood protein and genomic diagnostics, are frustrated with how little they are able to benefit their home market as opposed to overseas. They have tests that could save lives and money by earlier and fewer treatments. But the monolithic NHS cannot find it within its budget silos to buy such tests. Elsewhere in the world innovations that save lives and money are much more welcome.

In the main pathology field of clinical chemistry and immunoassay testing (~80% of all testing) only one new test has been widely adopted by the NHS in the past ten years: high-sensitivity troponin for detecting myocardial infarction or heart attack. That was adopted because a dominant private sector provider forced change on the sector. The NHS now values the test, but industry insiders say that left to their own devices, it is questionable how quickly even this test might have been adopted within the NHS.

Randox now has a complementary test for heart attack management, based on fatty acid binding proteins, but, though there is significant international interest, the firm is struggling to get the NHS to adopt it. The fatty acid proteins are released into the blood stream by damaged heart cells within 30 minutes, whereas troponin is released only when heart cells die after several hours. Combined with troponin, the test would more rapidly identify the one-fifth of patients with chest pain in Accident and Emergency who need treatment and the four-fifths who can be safely sent home, freeing up beds and saving about £225m a year.

Stem cells, gene therapy and gene editing promise a new generation of medicines for treating disease. But proteomics and genomics are transforming diagnosis into a cheap, rapid and accurate process that is probably going to have an even bigger effect on most people’s health. Britain is good at inventing this stuff, and selling it to the world, but terrible at applying it for the benefit of its citizens.

Matt Ridley's Blog

- Matt Ridley's profile

- 2180 followers