Matt Ridley's Blog, page 15

August 1, 2018

The European Union rejected genome edited crops

My Times column on the European Court of Justice's bizarre decision to treat genome edited crops as if they were transgenic:

The European Court of Justice has just delivered a scientifically absurd ruling, in defiance of advice from its advocate general, but egged on by Jean-Claude Juncker’s allies. It will ensure that more pesticides are used in Britain, our farmers will be less competitive and researchers will leave for North America. Thanks a bunch, your honours.

By saying that genome-edited crops must be treated to expensive and uncertain regulation, it has pandered to the views of a handful of misguided extremists, who no longer have popular support in this country.

Let’s compare two plant varieties: golden promise barley and a wheat resistant to a fungal pest called powdery mildew. The barley was derived from seeds bombarded with gamma rays at a nuclear facility in the 1950s, scrambling some of their genes, which had the happy if accidental result of making better malting barley. It became (and remains) a popular variety for brewing beer among (wait for it!) organic farmers.

The wheat was produced by Calyxt, a US company, last year using a genome-editing technique to tweak one part of one gene, introducing no foreign DNA. It will need less fungicide sprayed on it than normal wheat. The US government says it needs no special regulation. The EU has effectively said it will take Calyxt many years and vast sums of money to find out whether it might or might not approve the wheat for growing.

Calyxt and others like it won’t bother applying, so we will be deprived of the chance to use less fungicide. We will miss out on a new genome-edited potato variety that needs 80 per cent less spray. We are already missing out on GM varieties of maize and other crops that use much less insecticide and are proven safe by 25 years of consumption.

A 2014 German survey found that the introduction of genetic modification elsewhere in the world had reduced pesticide use by 36.9 per cent on average, while increasing yields by 21.6 per cent. No wonder we are having to import more of our cattle feed from the Americas.

The ruling condemns Britain to the innovation slow lane, denying us greener crops. It will deter investment and drive our world-class scientists to move abroad. As one Canadian professor said: “Great news for Canadian and American farmers today. EU based environmental NGOs have politically manipulated their legal system to drive every last cent of ag R&D out of the EU, guaranteeing their farmers will no longer be competitive. Hope all Europeans enjoy their future higher food prices.”

Welcome to our continuing regulatory alignment with the EU.

July 20, 2018

The secret lives of seabirds

This is recent Times feature article I wrote on the incredible new discoveries of what seabirds get up to far from land, and on the man who first visited seabird colonies with a scientific eye in the 1660s. It's sometimes still possible to write this kind of discursive essay! This one is about two of my friends from the same research group at Oxford.

Puffins on SkomerMATTHEW CATTELL/GETTY IMAGES

Off the coast of Pembrokeshire in south Wales lie two islands, Skomer and Skokholm. Home to more than 300,000 pairs of nesting seabirds, they are wild and raucous, rich in the sounds and sights (and guano smell) of seabird colonies. Every spring the Atlantic Ocean disgorges its birds on to rocky islands around Britain’s coasts to breed. By late summer the birds have vanished. The secret of what they do and where they go is becoming clear.

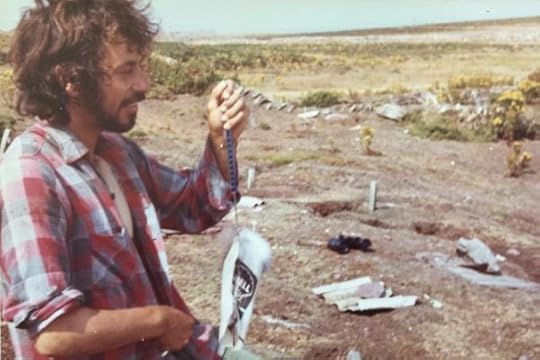

This summer puffins leaving Skomer will have GPS tracking devices and cameras attached to record where they go and what they do. It was on Skomer and Skokholm in the Seventies that two zoologists came to study the birds. Tim Birkhead landed on Skomer in 1972 to try to understand why the guillemots had declined to just 2,500 pairs (today they are up to 25,000). He has visited the island every spring since.

Tim Birkhead with young guillemots on Skomer

Michael Brooke arrived on Skokholm a year later to act as warden and study the Manx shearwater, a mysterious ocean wanderer that visits its nesting burrow at night and breeds almost exclusively in the British Isles. He has since travelled the world, studying seabirds on even more remote islands from the tropical Pacific to the Antarctic.

This year both men have written remarkable books that between them capture the excitement of cracking the secrets of birds, and seabirds in particular. Brooke’s Far From Land: the Mysterious Lives of Seabirds recounts in fascinating detail how new techniques such as satellite tracking are allowing scientists to find out what seabirds get up to on and under the sea.

Birkhead’s The Wonderful Mr Willughby: the First True Ornithologist uncovers the life of a scientist at the start of the scientific revolution who first made the study of birds, insects and fish into a scientific discipline with his friend and tutor from Trinity College, Cambridge, the botanist John Ray.

It was Francis Willughby who described the Manx shearwater, after a visit to the Calf of Man, off the Isle of Man, in August 1660. It was Willughby who sorted out the different names of the guillemot, razorbill and puffin in an era when identification of species was still uncertain. It was Willughby who noted the strangely pointed blue egg of the guillemot, adapted — Birkhead has recently proved — to make it stable on a sloping rock ledge.

In the Seventies Birkhead and Brooke might just about have seen each other in the distance on their separate islands, but it was back in Oxford during the winter that they would actually meet. Both were studying for their DPhils at the Edward Grey Institute, a university research group devoted to ornithology and named after the one-time foreign secretary (and Oxford chancellor) Sir Edward Grey, who wrote The Charm of Birds in 1927. I also studied at the EGI, as it was known, and came to know both seabird experts. Yet little did any of us dream how much knowledge would emerge by the time we were in our seventh decades.

Consider some of the stories that Brooke recounts in Far From Land. Tags attached to birds’ feathers or legs can now transmit their position and show whether they are flying or resting on the water. Fixed to Brooke’s favourite Manx shearwaters, the tags reveal that the birds travel to near the coast of southern Argentina in winter, via west Africa and Brazil, then return north in spring by a more westerly route closer to the coast of North America. They can easily cover 500 miles in a day.

KittiwakesGETTY IMAGES

The migration feats of seabirds are astonishing. An Arctic tern that my friend John Walton ringed on the Farne Islands off Northumberland in 1980 was recaptured and photographed with him in 2010. In those years it had migrated to Antarctic seas every winter, returning to Northumberland each spring, covering almost a million miles. Unlike John, it looked as young as ever.

Brooke recounts how today’s University of Oxford researchers have exposed the idiosyncratic migration patterns of individual puffins from Skomer, each making the same journeys in different winters: EJ09593 goes to Greenland in autumn, then back to west of Ireland in midwinter; EJ99355 goes north of the Hebrides, then south to the Bay of Biscay; EJ47617 heads for Iceland then to the western Mediterranean.

We now know that gannets from different British colonies partition the sea when foraging, with little overlap between colonies; guillemots can dive to 100m, and will even dive to feed at night in winter in almost complete blackness, somehow finding fish; and some young kittiwakes may spend their first year wandering as far as Baffin Bay, west of Greenland.

Artic ternMARY ANN MCDONALD/GETTY IMAGES

The stories that are emerging farther afield are even more spectacular. Brooke has studied Murphy’s petrel on the remote island of Henderson, an uninhabited speck that is part of the British Overseas Territory of Pitcairn in the Pacific. It takes 50 days for the petrels to hatch a single egg, with the incubation duty split three ways: male for 19 days, then female, then male again. When Brooke put geolocators on 25 birds he found that some of the off-duty ones travelled in search of food towards Peru, turning back only when about 2,500 miles from Henderson and covering up to 10,000 miles in less than three weeks.

Or consider how a single pair of Sabine’s gulls, nesting in the Canadian Arctic, spend the winter in separate oceans, the female off Peru, the male off South Africa, before reuniting on the tundra the next summer. Or that an emperor penguin may dive as deep as 560m and stay down for up to 20 minutes. Brooke’s book is stuffed with many such mind-boggling feats. To read it is like encountering a new and unknown blue planet for the first time.

Northern gannetJANE BARLOW/PA

This too was what gripped Willughby in the 1660s as he set out to understand the natural world, not by reading Aristotle or the Bible, but by using his eyes. It was a chance remark that led Tim Birkhead to become Willughby’s biographer. He was visiting the family home of Lord Middleton, Willughby’s descendant, when researching the history of ornithology for a previous book. He remarked that of the two Trinity men, Ray was the scholar, Willughby (who died young) the dilettante. Not so, said Middleton with vehemence.

Intrigued, Birkhead returned in 2014 and with Middleton opened the cabinet containing Willughby’s natural history collection. To his astonishment the bottom drawer contained a collection of cracked birds’ eggs inscribed with Willughby’s distinctive hand — the oldest extant birds’ egg collection in the world. Gradually Birkhead was drawn into the life of this extraordinary man, an early member of the Royal Society caught up in the thrill of letting the facts speak for themselves, a scholar of linguistics and a careful dissector of the birds he shot and the insects he caught.

Common eidersGETTY IMAGES

Birkhead is also keen on dissecting birds, although in his case ones that die naturally. Emulating Willughby, he dissected a bittern that struck a power line, finding facts about it that Willughby missed. Some years ago he and a colleague were among the first to describe and explain the enormous length, and explosive expansion, of penises in ducks, and the contorted shapes of female reproductive organs, designed to keep such intruding organs out, unless invited. But that’s another story.

Willughby and Ray were fascinated by seabird colonies — the “remarkable Isles, Cliffs, and Rocks about England, where Sea-fowl do yearly build and breed in great numbers”. They saw, but did not visit Skomer. They landed on the Farne Islands off the Northumberland coast, which I have visited every year for almost five decades (and whose advisory committee I sit on), and saw the same species I see today: “guillimets, scouts or razorbills, coulternebs [puffins], scarfs [shags], Cuthbert duck [eider], annet [kittiwake], mire crow [black-headed gull], pick-mire [tern]” and more.

RazorbillsGETTY IMAGES

This is reassuring — that these extraordinary seabird colonies have endured for centuries. Willughby records the systematic exploitation of seabirds in the 1600s. On the Calf of Man as many as 9,000 shearwater chicks were killed each year for sale as food, and the same was true in many seabird colonies. It was similar slaughter that caused the only extinction in the north Atlantic, of the flightless great auk, gone by the end of the 1840s.

Yet the colonies of other birds endured, and Skomer’s guillemots have bounced back from the oil spills that devastated them during and after the Second World War. These spills are now rare — indeed, we may have lived in a golden age for seabirds here. Numbers have possibly never been higher on the Farnes or Skomer, although Scottish seabird colonies have declined badly in recent decades because of a shortage of fish.

Michael Brooke on Skokholm

Now protected from human harvests, seabirds were also until recently spared the worst ravages of predation by large seagulls, their main predator, since most reserves had a policy of controlling gull numbers. Rats too have been extinguished from colonies such as Lundy and the Shiant islands in the Hebrides, allowing seabird numbers to expand.

In some ways it would have been wonderful to have lived when Willughby did and almost every observation, such as the description of a young shearwater, was new to science (if not to folklore). Yet how much better to live now when the entire world of seabirds, even far from land, is being chronicled in such magnificent detail by scientists such as Brooke and Birkhead.

Tim Birkhead’s research survives on public donations. To give, go to: justgiving.com/fundraising/guillemotsskomer.

The Wonderful Mr Willughby is published by Bloomsbury,

Far From Land is published by Princeton University Press

July 14, 2018

Electronic cigarettes and harm reduction

My recent Times essay on the history of vaping and why the UK became such a hub of electronic cigarettes:

Britain is the world leader in vaping. More people use ecigarettes in the UK than in any other European country. It’s more officially encouraged than in the United States and more socially acceptable than in Australia, where it’s still banned. There is a thriving sector here of vape manufacturers, retailers, exporters, even researchers; there are 1,700 independent vape shops on Britain’s streets. It’s an entrepreneurial phenomenon and a billion-pound industry.

The British vaping revolution dismays some people, who see it as a return to social acceptability for something that looks like smoking with unknown risks. Yet here, more than anywhere in the world, the government disagrees. Public Health England says that vaping is 95% safer than smoking and the vast majority of people who vape are smokers who are partly or wholly quitting cigarettes. The Royal College of Physicians agrees: “The public can be reassured that ecigarettes are much safer than smoking.”

Lots of doctors are now recommending vaping as a way of quitting smoking. It is because of vaping that Britain now has the second lowest percentage of people who smoke in the European Union. The youth smoking rate in the UK has fallen from 26% to 19% in only six years.

How did this happen here? It’s partly the fault of the advertising executive Rory Sutherland; he is the Walter Raleigh of this revolution. In 2010, he walked into an office in Admiralty Arch to see an old friend, David Halpern, head of David Cameron’s new “nudge unit”, formally known as the Behavioural Insights Team. Sutherland pulled out an electronic cigarette he had bought online, and inhaled. By then, several countries including Australia, Brazil and Saudi Arabia had already banned the sale of electronic cigarettes — usually at the behest of tobacco interests or public-health pressure groups. California had passed a bill banning them, though Arnold Schwarzenegger, then the governor, had vetoed it. It looked inevitable that Britain would follow suit.

“I was a very early convert,” Sutherland tells me now. “Partly because I was a longtime ex-smoker myself who found them much better than constant relapses; I was also interested in the placebo effect they offered by mimicking the act of smoking. But I was almost equally fascinated by the psychology of the people who instinctively wanted to ban them.”

Halpern took notice. He knew the theory of “harm reduction” — that it is more effective to give somebody the lesser of two evils than insist unrealistically on immediate abstinence. So he asked his nudge team to get digging. Over coffee at No 10, he was surprised to learn that even the anti-smoking group Ash was leaning in favour of ecigarettes. So when public-health nannies started calling for them to be banned, Halpern made sure the government resisted.

In his book Inside the Nudge Unit, Halpern wrote: “We looked hard at the evidence and made a call: we minuted the PM and urged that the UK should move against banning e-cigs. Indeed, we went further. We argued we should deliberately seek to make e-cigs widely available, and to use regulation not to ban them but to improve their quality and reliability.”

REX / IMAGE MANIPULATION BY JUSTIN METZ

The market did the rest. Entrepreneurs ranging from nightclub owners to former RAF pilots were already sniffing the opportunity to make and sell the devices. Experimental designs proliferated in Britain as nowhere else. As so often with innovators, all they needed was nobody getting in their way. They knew from the start that their target market was smokers desperate to quit, but who found gums, patches, acupuncture and hectoring did not work very well.

Professor Gerry Stimson of Imperial College, an expert on harm reduction, points out that it’s much easier to persuade people to do something if it is enjoyable rather than a painful chore: “For those trying to stop smoking, ecigarettes have profoundly changed the experience. For the first time, quitting cigarettes is no longer associated with being a ‘patient’ and with personal struggle.”

Sutherland recalls the early days: “I very quickly noticed that vaping could work as a substitute in a way patches didn’t — the throat hit, the trigeminal nerve effect, and so on. Besides, I often hung around in vape shops and could see lines of manual workers — the toughest groups to get to quit — queuing up to ‘try something cherry flavoured with a sub-ohm coil’ or whatever.” That vaping was far cheaper than smoking was a key incentive. Today, Britain has more than twice as high a vaping rate as the rest of the European Union: 5% versus 2%.

ATTACK OF THE VAPOURS

2.9 million The number of ecigarette users in the UK (of these, 1.5m have completely quit smoking cigarettes)

£400 Amount the average smoker in Britain spends every three months on cigarettes

£190 Amount the average ecig user in Britain spends every three months (if buying from supermarkets)

95% How much safer vaping is than smoking, according to Public Health England

The person who deserves the credit for inventing the modern ecigarette, a Chinese scientist named Hon Lik, had come up with the idea specifically to help himself quit smoking after watching his father die of lung cancer. While working as a chemist at the Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, he was smoking two packs a day. He tried and failed to quit by himself, then tried nicotine patches in 2001, but hated them.

The idea of electrical or electronic cigarettes had been around for decades: there was a patent in the 1930s, a prototype in the 1960s and a commercial product in the 1980s. But all came to nothing before the miniaturisation of batteries and electronics.

It so happened that Hon was working in a lab with access to liquid nicotine, used to calibrate other products. He had the idea of turning the liquid to vapour using ultrasound, but it did not work well, so he switched to a heating element. By 2003 he had filed a patent on his first practical prototype. “I already knew it would be a revolutionary product,” he laughs when I ask him about it, adding immodestly: “Some in China have called it the fifth invention — after navigation, gunpowder, printing and paper.”

The product went on sale after several months of toxicology testing and soon spread to Europe and America.

Nicotine is a chemical produced by tobacco plants and others in the nightshade family as a defence against pests: it is toxic to insects and other arthropods, and was once used as a pesticide; modern “neonicotinoid” insecticides are close cousins of the chemical. (Sparrows that build their nests out of cigarette butts in Mexico are less troubled by blood-sucking mites, a study has found.) In people, nicotine acts as a stimulant, but also a relaxant, by promoting the release of chemical messengers between brain cells.

True, nicotine is addictive, but so is caffeine, another anti-pest chemical produced by plants that has psychoactive effects, but is ingested by people in a less risky form than smoke. Smoking’s health risk comes not from nicotine, but from the chemicals created in the flame.

So giving smokers nicotine without giving them any smoke just has to be safer. In 2016, a series of key scientific papers from the lab of Dr Grant O’Connell, a scientist working for the ecigarette manufacturer Fontem Ventures, reported that smokers confined in a clinic for five days who switched to ecigarettes got the same amount of nicotine but much less exposure to the harmful toxicants known to cause smoking-associated disease risks, such as nitrosamine and carbon monoxide. After five days, the levels of harmful toxicants measured in their blood and urine was like that of smokers who went cold turkey over the same time. The subjects also had improvements to lung and heart function.

This year the team published one of the first long-term clinical studies, which monitored 209 smokers who used ecigarettes for two years. It found no evidence of any safety concerns or serious health complications in smokers after two years of continual ecigarette use. The studies that tabloid newspapers like to trumpet, about potential risks from vapour, by contrast, are all speculative extrapolations based on unrealistic levels of vapour in unnatural conditions. Even then, the effects are small.

For vaping to be beneficial, it does not have to be harmless. Surveys suggest 98% of vapers are smokers, so even if vaping carries a moderate risk, so long as it is less than the risk of smoking, there will be harm reduction.

In the 1980s, Britain pioneered “harm reduction”. Faced with a growing Aids epidemic among heroin addicts, the health secretary, Norman Fowler, chose a pragmatic rather than moralistic response: setting up needle exchanges and ignoring those who protested that this condoned drug use, undermined calls for abstinence and sent the wrong message to young people. It worked — Aids among injecting drug users slowed down. By 2010, only 1% of British drug injectors had HIV, compared with about 18% in America and 48% in Brazil — countries that were slow to adopt harm reduction.

Fortunately for vaping, some of the people involved in the needles episode found themselves in a key position when ecigarettes came along. Kevin Fenton, Rosanna O’Connor and Martin Dockrell had all worked on Aids or drugs and knew the benefits of harm reduction. They fought within Public Health England, against strong opposition from the chief medical officer and others, to get vaping seen in the same terms. In 2015, they succeeded and PHE came out with its bold statement that “ecigarette use is around 95% less harmful to health than smoking”.

Yet, despite official endorsement and the growing strength of the evidence for vaping’s harm reduction, public opinion has been moving against ecigarettes. More than 25% of people now erroneously believe vaping to be at least as harmful as smoking, up from 7% in 2013, thanks to tabloid headlines claiming as much.

Much of this misinformation came from vested interests. The pharmaceutical industry lobbied hard behind the scenes to defend its lucrative line in medicinal nicotine patches and gums against a new competitor. Both patches and smoking cessation services have lost about half their business since 2011.

As ever with prohibition campaigns, this was a coalition of what the economist Bruce Yandle once called “bootleggers and Baptists”: profiteers and preachers. Much opposition to vaping came, and comes, from puritans horrified at the thought that somebody, somewhere, might be enjoying themselves. If quitting smoking is pleasurable then it must be sinful.

In 2014, at the height of the ebola epidemic, the director-general of the World Health Organisation, Margaret Chan, made it clear that she considered opposing vaping a high priority. The European Commission, egged on by the British government, which had temporarily given in to the nannies, also tried to kill the industry by demanding they be regulated as medicinal products. The European parliament killed the proposal, but agreed to include in the Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) a ban on high-strength eliquids and the advertising of ecigarettes.

This directive, which came into force in 2017, has slowed the growth of vaping in the UK. Strong liquids are the ones heavy smokers need if they are to switch. Not being able to advertise hamstrings the vaping industry’s attempts to reach smokers who have been misled into thinking it’s more harmful than smoking. The tobacco industry is, of course, the devil incarnate for many people working in public health. The industry has joined the harm-reduction bandwagon because it is spooked by the rise of vaping, fearing it might end up being killed by innovation in the same way Kodak was. But this volte-face hardened many in the medical profession against vaping: if big tobacco is into this, it must be bad.

Opponents of vaping still worry it is a gateway into smoking, fearing the young are being lured into nicotine addiction by vaping before moving on to smoking. Clive Bates, a former civil servant and campaigner for progressive causes, lambasts the gateway argument as patronising: “Kids have been weaponised in an activist battle to bend the adult world out of shape where it serves an abstinence-only agenda.”

Bates points out that smoking rates among young people are falling faster since 2010 than they were before, that surveys show the majority of underage vapers are former smokers or would-be smokers, and that young people give harm reduction as their main reason for vaping when asked. As with adults, ecigarettes look as though they are protecting children against smoking much more than luring them into it. In short, the gateway argument just does not hold up.

The argument that vaping cannot yet be proven safe, so must be assumed to be unsafe, is an example of what can go wrong with the “precautionary principle”. If an existing technology is killing people, and a safer alternative comes along to save their lives, then waiting for watertight evidence about the risks of the new technology is effectively culpable homicide. The precautionary principle thus applied holds new technologies to a higher standard than existing ones, stifling beneficial innovation.

There’s also the social-justice impact of vaping. Smoking is now more common among poor people than rich people. Current tobacco-control policies make this regressive impact worse by taxing and stigmatising the poor more than the rich. Vaping offers to reduce the cost of nicotine addiction greatly, helping the poor.

Most premises insist on sending vapers out in the cold to stand shivering among smokers in winter, treating the two groups the same. This, say vaping’s proponents, is madness. It reinforces the false message that vaping is just as harmful as smoking. Further, it actually makes it harder to quit by exposing them to temptation.

One of the advantages of ecigarettes is that you don’t have to finish them. Take one quick puff and put it back in your pocket. With a cigarette, you feel obliged to smoke the whole thing. If a worker has to trek out into the street to vape, he will take more puffs than if he can do it at his desk. And he will waste more of his employer’s time.

It’s actually easy to vape discreetly, with no visible vapour and no smell, so lots of vapers are probably already doing it surreptitiously at work. I neither smoke nor vape, but I have sometimes challenged vaping friends to take a secret puff in the Houses of Parliament; so far they have always got away with it. The “cloud-chaser” vapers who produce huge fogs of vapour are the exceptions, not the rule, though they dominate the pictures in the media. Imagine a firm that said vapers can do it at their desk as long as their neighbours don’t object, or adopted a policy similar to that of using a mobile phone. A smoker working at such a firm would have a big incentive to switch.

The New Nicotine Alliance, which campaigns for nicotine harm-reduction, recently launched a campaign to challenge property owners to drop their policies of treating vapers like smokers. PHE states “that ecigarette use is not covered by smoke-free legislation and should not routinely be included in the requirements of an organisation’s smoke-free policy”, a recommendation routinely ignored by local councils and most businesses.

Britain stumbled into world leadership of the vaping industry. It’s a textbook example of disruptive innovation: a new technology, a decision not to block it, a history of harm reduction, a flowering of experiments, lots of research into the impacts, a lot of lives saved and financial benefits shared between consumers and producers. Plus a sudden acceleration of the race to extinguish for ever a nasty habit. And all at zero cost to the taxpayer. What’s not to like?

June 18, 2018

Frustrate their knavish tricks

My Times column on the parliamentary battle over Brexit:

Dominic Grieve, MP, and Viscount Hailsham are clever barristers both, and agreeable company. I was at Oxford with one, sit in the Lords with the other, and count them as friends. But what they are up to infuriates me. Their amendment to the EU Withdrawal Bill — for it is a joint effort — is a masterpiece of ingenuity and subterfuge, and it has nearly succeeded in wrecking Brexit altogether, which was undoubtedly its purpose all along. Tonight in the Lords comes the latest and probably not the last battle.

Before the 2017 election Mr Grieve said he did not want to “fetter the government’s hands in negotiations, or indeed the government’s right to walk away from the negotiations”. Like many at that time he wanted to get the best possible deal in the softest possible Brexit. What changed?

After the election, a new opportunity arose. Somewhere, maybe in Brussels, maybe in London, a group of determined Remainers must have met and decided upon a plan, not to soften or improve Brexit but to kill it, by the device of ensuring that such a bad deal was on the table that the British people might change their minds. Who met where and when we may never know, but let’s picture a scene: a pack of Blairite spin doctors, a shoal of well-watered Eurocrats, a posse of Tory rebels, a pomposity of QCs, an incantation of retired mandarins, and, off stage, an affluence of money men.

Their best weapon would be to amend a vital bill that ostensibly had nothing to do with the negotiations, but was designed to make the statute book fit for purpose after withdrawal. But how? Lots of ideas came forward, such as removing the date of exit from the bill, but it was the demand for a so-called meaningful vote in parliament on the negotiations that came to be the key weapon, because it was the subtlest. And now, the Commons having disposed of all the rest, it is the only one left.

That wily old veteran of Euroscepticism Sir Bill Cash MP, chairman of the European Scrutiny Committee, saw quite clearly some months ago what was afoot. I recall him saying then that the Hailsham amendment in the Lords was a dangerous improvement on the Grieve amendment in the Commons and was by far the cleverest threat to any Brexit at all, let alone a clean one.

By giving parliament control of the negotiations should no deal be reached by a certain date, it looked innocuous and democratic but effectively removed all threat of Britain leaving without a deal: for there would be no parliamentary majority for any particular tactic, let alone playing chicken with Brussels. That would give Michel Barnier and the European Commission the certainty that they could stonewall till parliament stepped in and then concede nothing and demand everything without fear of Britain walking away.

This in turn would ensure that we faced a worse outcome even than continuing membership of the EU — and than no deal. Namely a vassal state, a Napoleonic province. No veto, no rebate, no council membership, no parliamentary representation, but all the rules, all the external tariffs, all the anti-innovation, crony-capitalist regulation, and an immigration policy that would continue to discriminate in favour of Europeans claiming benefits and against Indian entrepreneurs wishing to invest.

This was an option that the British people would surely reject, either in a second referendum or in a general election. Lord Malloch-Brown, head of Best for Britain (an organisation apparently devoted to achieving the worst deal for Britain), has made this clear: “We must win the meaningful vote . . . That is likely to trigger a new referendum, or election.”

This explains why various versions of softer Brexit have attracted so little interest from the Tory rebels and their allies. (The floundering and disintegrating Labour front bench mostly misses this point.) Customs arrangements, EEA membership and all other suggestions of compromise are no longer acceptable to the Grievites. Any deal is worse than a bad deal.

I repeat: the Grievites are no longer interested in getting us a better deal; they are determined to get us such a bad deal that we change our minds. That’s been their strategy ever since the election, and it was obvious it was being carefully co-ordinated with Mr Barnier’s team long before a cross-party group of Remainers was caught slipping disloyally into the European Commission’s London headquarters last week.

Last week, to get his way and keep the game alive, Mr Grieve had to play clever. He dared not force a vote on his amendment in the Commons, seeing it was safer to wring some vague concession from the prime minister with last-minute threats of rebellion. He could then cry treachery when the promised concession was turned into the words of a Lords amendment. Given his visit to the commission, how he had ambushed the prime minister at the last minute and how his and Lord Hailsham’s amendment is designed to get the worst deal for Britain, the cry of treachery is a bit rich.

But it is, as Hugh Bennett of Brexit Central pointed out, revealing because Theresa May’s amendment “is already an uncomfortably large concession from the government. It gives the rebels everything they have asked for except the ability to block Brexit altogether. There are no honest grounds for opposing it unless that is your true motivation.” It is disingenuous and discreditable of Mr Grieve and Lord Hailsham to keep pretending against all evidence that they are only trying to improve the government’s negotiating position.

The negotiating stance of Mr Barnier has all along been intended to discourage others from leaving the EU rather than to find an outcome that benefits ordinary people, even in France, let alone Britain. Hence his demand for a generous exit payment from Britain before agreeing to anything else, his playing with fire over Ireland and his taking a self-defeating and probably illegal position over the Galileo satellite project just to spite us. Even Hilary Benn MP called the commission’s Galileo stance counterproductive and “frankly, insulting”.

But there is method in its madness. Why, in hundreds of hours of debate in the Lords have I yet to hear a Remainer criticise Mr Barnier for these knavish tricks? Because they see his purpose is to get us such a bad deal that we change our minds, and they share that goal.

May 24, 2018

GDPR Regulations

The new General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) are coming into effect on 25th May 2018, and I know you will have received many emails on this subject.

You are currently subscribed to my blog. On that basis, as somebody who has actively subscribed, I trust you will want continue to receive these emails. If you would prefer to not receive these emails please unsubscribe by clicking on the unsubscribe button at the bottom of this or any future email.

Matt Ridley

April 23, 2018

AI in the UK: Ready, willing and able?

My Times column on artificial intelligence:

As a member of the House of Lords select committee on artificial intelligence, whose report is released today, I was struck by two things during the course of our inquiry: how well placed Britain could be to take advantage of the new technologies that go under the name of AI, should we choose to play our cards right; and how pervasive and invisible this technology will prove to be.

The first point was driven home during an evidence session with a more than usually brilliant German professor, Wolfgang Wahlster, chief executive of the German Research Centre for AI. He said: “We have a very special approach that is based on Germany’s industrial strengths . . . This is quite different from the US approach, which is based more on internet services. We are more in the physical domain; you know that Germany is well known for its engineering and manufacturing.” He added: “Historically, the UK was the leading country in Europe in AI. It started in Edinburgh.”

2001: A Space Odyssey encouraged an idea of humans and machines at oddsALAMY

The point is, we can play to our strengths. The Germans will make clever washing machines and cars, the Americans and Canadians will concentrate on the internet, the Chinese will get worryingly good at smart espionage, but there is a niche for Britain, a country with a hotspot of world-beating expertise in biomedicine, finance, law and research as well as a reputation for getting ethical regulation right, for example in reproductive technologies. We will never compete with the United States or China in investment, but there will be an opportunity for whoever unleashes a torrent of well-channelled experiments to transform healthcare, the law and finance. The UK has more tech startups and more leading universities than the rest of Europe put together, and they rub shoulders with doctors and lawyers in Shoreditch, east London.

The most high-profile achievement of AI in recent years was the victory of AlphaGo, a program developed by the London-based DeepMind, over Lee Sedol, a world champion at the game of Go, in 2016. Watched live by up to 60 million people across Asia, the six-day tournament showed the underdog program, badged with a Union Jack, unexpectedly defeating the Korean equivalent of Garry Kasparov by four games to one, to gasps of excitement and groans of despair in a packed press room. AlphaGo’s 37th move in the second game was considered suicidal; it is now thought stunningly original. DeepMind is owned by Alphabet, Google’s parent company, having been bought in 2014 on the condition that it stayed in London and expanded under its founder, Demis Hassabis. British technology has never had such free PR.

True, games are only games. What counts is how far AI seeps into everyday life and transforms the prosperity of humankind. The main gains to society from electricity, say, or the internal combustion engine, are not the profits of the electricity companies or carmakers, but the efficiencies we all experience in our normal lives as a consequence of having those technologies. It will be the same with AI: consumers, not producers, are key. So while a thriving British AI development industry would be great, it’s not the main prize.

A surprising amount of AI already does pervade our lives. As our report details, the technology already exists to wake you at the right part of the sleep cycle, allow you to select a radio station via a voice-activated digital assistant, get personalised content on your smartphone, avoid traffic jams thanks to live updates to your car’s navigation system, find cancer in a scan, detect potential bank fraud, get a suggestion for what movie to watch, set the washing machine going, and so on. All of these would have seemed indistinguishable from magic a few years ago, but are now almost taken for granted.

The peculiar fact is that is as soon as something becomes possible in the world of AI, we stop calling it intelligence and think of it as better software. The present excitement is over specialised AI applications, not general intelligence of the kind that could rival a rounded human being. But at their heart lies a new approach. Whereas the previous generation of AI was based on “expert systems” pre-loaded with human expertise, today’s algorithms know almost nothing at the start, but crunch lots of data to learn how to do something. It is the access to deep draughts of data, and the ability to learn from them, that make the difference. Which is, of course, the issue. The handling of personal data by all-too-human intelligence has turned into the biggest ethical challenge of this brave new world. Not job losses: automation has led to more employment, not less, in every technological revolution since the threshing machine, and will this time too, in my view, though it is now lawyers and medics who may have to readjust rather than farmhands and factory workers. Not inequality: nothing is proving more egalitarian than the smartphone, and AI should likewise be mostly available to rich and poor alike.

And not Hal, the computer that learns to be malevolent in defence of its off switch in 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that this year celebrates its 50th anniversary. This week the hip speech-fest known as TED will take place in Vancouver, and it features the usual dystopian worries about AI. For instance, Max Tegmark, president of the Future of Life Institute at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, will argue that “in creating AI, we’re birthing a new form of life with unlimited potential for good or ill. It’s truly urgent that we begin imagining different AI futures so that we can build the one we want. We only have one shot at this.” Instead, society must grapple with the dilemma of preserving people’s privacy and ownership of their data, while letting machine-learning algorithms harvest insights of value to everybody. The starry-eyed optimism that greeted, for example, the Obama campaign’s use of Facebook data in 2012 has given way to rage at similar practices used by the Trump campaign or Russia. Is there a sensible compromise to be found? Of course.

Technology has a habit of changing everything and nothing at the same time. The rise of AI will make life richer, better, more interesting, and then, without any fuss at all, be taken for granted, as electricity and cars are. Yet the same old, all-too-human ethical and political dilemmas about how much power to allow the state, or private enterprise, will persist.

April 9, 2018

The coagulated economy

My Times column on the rent-seeking crony-capitalists who stifle innovation:

While the world economy continues to grow at more than 3 per cent a year, mature economies, from Europe to Japan, are coagulating, unable to push economic growth above sluggish. The reason is that we have more and more vested interests against innovation in the private as well as the public sector.

Continuing prosperity depends on enough people putting money and effort into what the economist Joseph Schumpeter called creative destruction. The normal state of human affairs is what The jurist Sir Henry Maine called a “status” society, in which income is assigned to individuals by authority. The shift to a “contract” society, in which people negotiate their own rewards, was an aberration and it’s fading. I am writing this from Amsterdam and am reminded we caught the idea off the Dutch, whose impudent prosperity so annoyed the ultimate status king, Louis XIV.

In most western economies, it is once again more rewarding to invest your time and effort in extracting nuggets of status wealth, rather than creating new contract wealth, and it has got worse since the great recession, as zombie firms kept alive by low interest rates prevent the recycling of capital into new ideas. A new book by two economists, Brink Lindsey and Steven Teles, called The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality, argues that “rent-seeking” behaviour — the technical term for extracting nuggets — explains the slow growth and rising inequality in the US.

They make the case that, in four areas, there is ever more opportunity to live off “rents” from artificial scarcity created by government regulation: financial services, intellectual property, occupational licensing and land use planning: “The rents enjoyed through government favouritism not only misallocate resources in the short term but they also discourage dynamism and growth over the long term.”

Here, too, hidden subsidies ensure that financial services are a lucrative closed shop; patents and copyrights reward the entertainment and pharmaceutical industries with monopolies known as blockbusters; occupational licensing gives those with requisite letters after their name ever more monopoly earning power; and planning laws drive up the prices of properties. Such rent seeking redistributes wealth regressively — that is to say, upwards — by creating barriers to entry and rewarding the haves at the expense of the have-nots. True, the tax and benefit system then redistributes income back downwards just enough to prevent post-tax income inequality from rising. But government is taking back from the rich in tax that which it has given to them in monopoly.

As an author, my future grandchildren will earn (modest) royalties from my books thanks to lobbying by American corporations to extend copyright to an absurd 70 years after I am dead. Yet there is no evidence that patents and copyrights incentivise innovation, except in a very few cases. Indeed, say Lindsey and Teles, the evidence suggests that “rents that now accrue to movie studios, record companies, software producers, pharmaceutical firms, and other [intellectual property] holders amount to a significant drag on innovation and growth, the very opposite of IP law’s stated purpose.”

[Thomas Babington Macaulay MP summarised an early attempt to extend copyright in a debate thus: "The principle of copyright is this. It is a tax on readers for the purpose of giving a bounty to writers. The tax is an exceedingly bad one; it is a tax on one of the most innocent and most salutary of human pleasures; and never let us forget, that a tax on innocent pleasures is a premium on vicious pleasures." A correspondent sends me the following details of this appalling saga: "Someone noted that there is a divergence in copyright term in the European Union. All the then member states protect works for the life of the author plus fifty years while West Germany alone protects works for the life of the author plus seventy years. Immediately the copyright publishers suggested this as something in need of harmonisation. But instead of harmonising down to the norm, all the member states were lobbied to harmonise up to the unique German standard. As a result, Adolf Hitler's "Mein Kampf" which was going out of copyright in 1995 was suddenly revived and protected as a copyrighted work throughout the European Union. Gilbert and Sullivan operettas whose copyright had been controlled by the stultifying hand of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company found themselves in a position to once again stop anyone else performing Gilbert and Sullivan works or creating anything based upon them. It is not surprising that, following a brief flowering of new creativity when the Gilbert and Sullivan copyrights initially expired (e.g. Joseph Papp's production of Pirates on Broadway and the West End stage), since their revival by the European Union harmonisation legislation their use have become effectively moribund. A generation of young people are growing up without knowing anything about Gilbert and Sullivan - an art form which, it can be argued, gave birth to the modern American and British musical theatre."]

As for occupational licensing, Professor Len Shackleton of the University of Buckingham argues that it is mostly a racket to exploit consumers. After centuries of farriers shoeing horses, uniquely in Europe in 1975 a private members bill gave the Farriers Registration Council the right to prosecute those who shod horses without its qualification.

Then there are energy prices. Lobbying by renewable energy interests has resulted in a system in which hefty additions are made to people’s energy bills to reward investors in wind, solar and even carbon dioxide-belching biomass plants. The rewards go mostly to the rich; the costs fall disproportionately on the poor, for whom energy bills are a big part of their budgets.

An example of how crony capitalism stifles innovation: Dyson found that the EU energy levels standards for vacuum cleaners were rigged in favour of German manufacturers. The European courts rebuffed Dyson’s attempts to challenge the rules, but Dyson won on appeal and then used freedom of information requests to uncover examples of correspondence between a group of German manufacturers and the EU, while representations by European consumer groups were ignored.

So deeply have most businesses become embedded in government cronyism that it is hard to draw the line between private, public and charitable entities these days. Is BAE Systems or Carillion really a private enterprise any more than Oxford University, Oxfam, Oxfordshire county council or the NHS? All are heavily dependent on government contracts, favours or subsidies; all are closely regulated; all have well-paid senior managers extracting rent with little risk, and thickets of middle-ranking bureaucrats incentivised to resist change. Disruptive start-ups are rare as pandas; the vast majority work for corporate brontosaurs.

Capitalism and the free market are opposites, not synonyms. Some in the Tory party grasp this. Launching Freer, a new initiative to remind the party of the importance of freedom, two new MPs, Luke Graham and Lee Rowley, not only lambast fossilised socialism and anachronistic unions, but also boardrooms “peppered with oligarchical and monopolist cartels”.

One of the most insightful books of recent years was The Innovation Illusion by Fredrik Erixon and Björn Weigel, which argues that big companies increasingly spend their profits not on innovation but on share buybacks and other “rents”. Far from swashbuckling enterprise, much big business is “increasingly hesitant to invest and innovate”. Like Kodak and Nokia they resist having to reinvent themselves even unto death. Microsoft “was too afraid of destroying the value of Windows” to go where software was heading.

As a result, globalisation, far from being a spur to change, is an increasingly conservative force. “In several sectors, the growing influence of large and global firms has increasingly had the effect of slowing down market dynamism and reducing the spirit of corporate experimentation”.

The real cause of Trump-Brexit disaffection is not too much change, but too little. We need to “radically reduce the restrictive effect of precautionary regulation” and promote a new regulatory culture based on permissionless innovation, Erixon and Weigel say. “Western economies have developed a near obsession with precautions that simply cannot be married to a culture of experimentation”. Amen.

April 8, 2018

Cities are the new Galapagos

My Times column on the evolution of urban wildlife:

Easter Monday bank holiday feels like a good moment to put aside politics and consider something far more portentous: evolution. Recently I was walking alongside a canal in central London, surrounded by concrete, glass, steel and tarmac, when I heard the call of a grey wagtail. Looking to my right I saw this bold, fast, yellow-bottomed bird, which I associate with wild rocky rivers in the north, flitting into a canal tunnel. Later that week I stared up at two peregrine falcons circling high above parliament — and got funny looks from passers-by.

Like other cities, London is increasingly home to exotic wildlife and is as biodiverse as some wildernesses. Mumbai has leopards, Boston turkeys, Chicago coyotes and Newcastle kittiwakes. Suburbs are already richer in wildlife than most arable fields in the so-called green belt, making environmental objections to housing development perverse. Gardens, ledges, drains, walls, trees and roofs are full of niches for everything from foxes to flowers and moths.

Two Czech scientists counted the species of plants in the city of Plzen compared with a similar area of surrounding countryside. In the city the number of species had risen from 478 in the late 19th century to 773 today. In the countryside it had fallen from 1,112 to 745.

Since most animals have shorter lifespans than us and no welfare state, they are genetically adapting faster to the concrete world than we are. A fascinating book by a Dutch biologist, Menno Schilthuizen, called Darwin Comes to Town, documents just how wide and deep this urban wildlife evolutionary pulse is. We have unleashed an unprecedented burst of natural selection.

Once a species thrives in a man-made habitat, it may find itself giving up living elsewhere. This must have happened to swallows and sparrows a long time ago: they became so successful nesting in buildings that the genes of their tree or cliff-nesting cousins died out. Today it is probably happening with peregrine falcons and herring gulls: urban ones are having more young than rural ones, so will soon swamp the whole species with their genes.

Urban landscapes present new evolutionary pressures. Street lights confuse and massacre moths and cause songbirds insomnia. Metal concentrations can be toxic. Noise drowns out birdsong. Instead of remaining insuperable, however, these novelties bring out the ingenuity in evolution. Urban insects may be changing their genetic make-up so they no longer fly towards lights: suicide as a selective force. One Swiss study found that ermine moths from the countryside are almost twice as likely to fly towards a light as their cousins from the city of Basel.

Parakeets are common in London and have become used to human contactALAMY

Other examples of urban evolution abound. Killifish in polluted American harbours have developed genetic resistance to the effect of polychlorinated biphenyls, an industrial pollutant. Acorn ants in Cleveland, Ohio, can withstand high temperatures better than ants from the country — which is necessary because city temperatures tend to be higher. Mexican sparrows that incorporate cigarette butts in their nests have fewer bloodsucking mites feeding on their chicks because nicotine is a pesticide.

Birds sing higher-pitched songs in cities — the ones that stayed low having attracted fewer mates over the sound of traffic. In the countryside, the opposite is true: female great tits mated to high-pitched males are more likely to stray. So the species is splitting into soprano town-tits and bass country-tits. In the Netherlands, chiffchaff warblers and grasshoppers both sing higher-pitched songs if they live near busy roads. Pigeons in big cities have darker plumage because melanin pigment binds zinc, excreting it from the body and improving the birds’ health.

Human beings, too, have been forced to evolve by urbanisation. For centuries cities such as London were population “sinks”, killing more people with disease than their birth rates could match and sustaining their population only by immigration from the countryside. That put a premium on genetic mutations that resisted urban diseases. People with long histories of urban living tend to have genes that resist tuberculosis and leprosy, for example. It would not be a surprise to find that an ability to tolerate continual noise may also be partly genetic as well as learnt.

Walking to the Tube in London each morning at this time of year I hear goldcrests and goldfinches, parakeets and dunnocks, wrens and long-tailed tits, none of which lived in the middle of cities in my youth. Experiments show that urban tits, finches and sparrows are less “neophobic” than rural ones: they have evolved to be less fearful of the appearance of new objects on bird tables, for example. Compared with the egg-stealing, catapult-wielding youths of previous centuries, young people today simply do not pester animals as much.

Blackbirds first showed up in London in the 1920s, later than in continental cities. Studies in France and the Netherlands found that urban blackbirds were rapidly diverging from rural ones. They tend to have shorter beaks and wings, longer intestines and legs, as well as higher-pitched songs. They may soon count as a separate species, just as town pigeons are very different from their rock-dove cousins. Dr Schilthuizen argues that “as the urban environment expands its reach, it will become more and more an ecosystem in its own right, writing its own evolutionary rules and running at its own evolutionary pace”. Wildernesses experience very slow rates of species formation because they are already mature ecosystems. Cities, like archipelagos of islands, experience a much faster rate of change.

The immediate reaction of many people to this tale of urban biodiversity might be to lament the human interference in nature and discount urban wildlife as artificial. We sometimes despise rather than admire creatures that become urban: town pigeons are “feathered rats”, urban foxes “mangy vermin”.

An increase in urban wildlife cannot compensate for the extinction crisis in wilder spaces. But thanks to increased awareness and new techniques, we have shown we can halt extinction if we try.

In recent centuries we have lost 61 of 4,428 species of mammals and 129 of 8,971 birds. Thanks to the genetic change that is happening in the urban Galapagos, we can create new species too, albeit unwittingly. A small cheerful thought for a festival of chicks and bunnies.

April 3, 2018

Genes appear to explain most of the success of selective schools

My Times column on genes, intelligence and selective schools:

The good news is you can save on school fees. A new study finds that selective schools add almost nothing to the exam results of students, because the advantages teenagers come out with are mainly ones they arrived with, and are for the most part genetic. The bad news is that this implies genetic stratification of society is happening, and more than we thought. But then that is bound to happen in a meritocracy. If you make everything else equal, differences will be increasingly determined by genes.

The new study comes with impeccable credentials, from a team led by Robert Plomin, a professor at King’s College London and the acknowledged leader in the genetics of intelligence. Co-authors include the researcher Emily Smith-Woolley and the prominent school reformer (and social media witch-hunt victim) Toby Young, whose father coined the word “meritocracy” 60 years ago.

It is no longer controversial that genes influence intelligence. Studies of twins repeatedly show that in typical western society, measures of general intelligence derived from IQ tests have about 30 per cent heritability (that is, 30 per cent of the variation between people can be explained by their genes) in childhood, 40 to 50 per cent in adolescence and 60 per cent in adulthood. This increasing heritability with age may appear paradoxical but it makes sense: adults are free to find their own intellectual level, whereas children can be forced by pushy parents and good schools, or by bad friends and bad schools, into seeming less like they really “are” deep down.

The politics of this are also paradoxical. The left has tended to downplay the role of genes in intelligence, while the right has welcomed it. Yet if you argue that nurture is everything and nature is nothing, then you effectively condemn people who went to poor schools to being second-rate and irredeemable; if you think nature matters, then it follows that there are gifted people in bad schools who the system should discover and rescue through affirmative action. Professor Plomin’s own talents were recognised after an IQ test: he came from a home with no books and neither parent went to university.

Likewise, when scientists began speculating about whether homosexuality had a genetic contribution, about 20 years ago, some commentators were surprised to realise that gay people generally liked the idea, because it implied that being gay was not a “choice” but inherent to who they were.

Transgender activists have also welcomed recent work implying a genetic contribution to transgender identity. It supports the notion “that transgender is not a choice but a way of being”, as one geneticist put it. The same switch to thinking that genetics tends to be on the side of the progressives has not yet occurred with respect to intelligence.

Knowing that genes matter is not the same as knowing which genes matter. For a long time it was impossible to match intelligence to any particular genes. That has changed thanks to the ability to detect the influence of many hundreds of genes, each of small effect, in large samples of genotyped people. The resulting “genome-wide polygenic scores” (GPS), are measures of which gene combinations are present. Those with a high score proved twice as likely to go on to university as those with low.

So it is now possible to see whether good schools get good results because of good teaching or good selection. The new study looked at a representative sample of 4,814 students in non-selective state schools, selective state schools (grammars) and selective private schools. The students in selective schools did better at GCSEs than those in comprehensives, as expected. But the scientists then compared the genes of the three groups, using the GPS scores that predict the number of years spent in education.

They found that three times as many students in the top tenth of the population on a GPS score went to a selective school compared with the bottom tenth. Once they controlled for factors involved in pupil selection, the variance in exam scores at age 16 explained by school type dropped from 7 per cent to less than 1 per cent. “These results show that genetic and exam differences between school types are primarily due to the heritable characteristics involved in pupil admission.”

Crikey. So all those talented Etonians were pretty talented to start with. I’m an underachiever, having gone to the same school as the last prime minister, the current foreign secretary, the Archbishop of Canterbury and recent winners of a Nobel prize for medicine (Sir John Gurdon) and an Oscar (Eddie Redmayne).

Of course, the genes involved in making somebody succeed in school may not directly determine intellect; they could somehow have caused the child’s parents to be more conscientious and read to them every night, or they could have affected the child’s appetite rather than aptitude for learning. And parents send their children to private schools for reasons other than educational achievement: to marinate their kids in a certain social set, say.

Genes cannot be wished away. As the Harvard geneticist David Reich said: “Well-meaning people who deny the possibility of substantial biological differences among human populations are digging themselves into an indefensible position, one that will not survive the onslaught of science.”

When it comes to gender, some sex differences are genetic; breasts and beards are not social constructs. It is harder to decide which sex differences in behaviour are derived from nature, but again the paradox of heritability provides a clue. Two psychologists last month published a paper showing that in countries where women are least discriminated against, women are most under-represented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. The percentage of STEM graduates who are female is twice as high in Turkey, Algeria and Tunisia as in Finland, Sweden and Norway. It appears that the more freedom girls have, the less likely they are to choose STEM subjects.

Today we rightly try to make sure that any differential outcomes by sex, race or education are not caused by discrimination. But the result is that we will maximise the contribution of innate preferences and abilities instead. A perfectly meritocratic society would be one in which people who went to Oxford were genetically, not socially, advantaged.

March 26, 2018

Energy return on energy invested and the promise of fusion

My Times column on Britain's energy options:

Until 2004 Britain was a net energy exporter. Today, it imports about half its energy. Some of that, in the form of coal and liquefied natural gas, comes directly from Russia, which also supplies a third of Europe’s gas through pipelines. The unprecedented “gas deficit warning” of March 2 was a sharp reminder of our dependence on imports.

Yet Britain is swimming in energy. Enough sunlight falls on the country to power the economy many times over. Wind, wave, water and tidal power cascade over us. There is wood in our forests. There are hot rocks beneath Cornwall and Durham, gas under Lancashire and enough coal under the North Sea to last centuries. We could easily buy sufficient uranium to keep us going indefinitely. And if we were to crack nuclear fusion, all we would need is a little bit of water and some Cornish lithium.

So what’s the problem? The human race has a plethora of options for powering civilisation in the 21st century, not a dearth. The problem is not energy, but energy conversion. Economic growth is effectively a matter of turning energy into complex structures that can be energised to do work. Energy conversion is the lifeblood of civilisation. Just as biology harnesses energy to build bodies and ideas, so human society captures energy to make physically improbable entities such as buildings, governments and social-media platforms. Energy conversion enables us to avoid entropy, the drift towards chaos.

The modern world stands on a cairn built by energy conversions in the past. Just as it took many loaves of bread and nosebags of hay to build Salisbury Cathedral, so it took many cubic metres of gas or puffs of wind to power the computer and develop the software on which I write these words. The Industrial Revolution was founded on the discovery of how to convert heat into work, initially via steam. Before that, heat (wood, coal) and work (oxen, people, wind, water) were separate worlds.

To be valuable, any conversion technology must produce reliable, just-in-time power that greatly exceeds — by a factor of seven and upwards — the amount of energy that goes into its extraction, conversion and delivery to a consumer. It is this measure of productivity, EROEI (energy return on energy invested), that limits our choice.

You could make your own electricity on an exercise bicycle, eating organic ice cream as fuel, but such a system would have wildly negative EROEI once you include the energetics of farming cattle and making ice cream. It would also produce a pathetic trickle of power: about 50 watts (joules per second). The average Briton uses about 4,000 watts, as much energy as if she had 240 slaves on exercise bicycles in the back room, pedalling eight-hour shifts. That’s roughly what “civilisation” looked like in ancient Egypt or China.

Old tin mine in Cornwall; the county is a source of lithium for nuclear fusionGETTY IMAGES

By the EROEI criterion, biofuel is a disastrous choice, requiring about as much tractor fuel to grow as you get out in ethanol or biodiesel. Wind power has a low energy return, because its vast infrastructure is energetically costly and needs replacing every two decades or so (sooner in the case of the offshore turbines whose blades have just expensively failed), while backing up wind with batteries and other power stations reduces the whole system’s productivity. Geothermal too may struggle, because turning warm water into electricity entails waste. Solar power with battery storage also fails the EROEI test in most climates. In the deserts of Arabia, where land is nearly free, sunlight abundant and gas cheap, solar power backed up with gas at night may be cheap.

Fossil fuels have amply repaid their energy cost so far, but the margin is falling as we seek gas and oil from tighter rocks and more remote regions. Nuclear fission passes the EROEI test with flying colours but remains costly because of ornate regulation.

Which brings me to nuclear fusion, a process potentially with a wildly positive EROEI (it fuels the sun and the H-bomb) but that so far has proved impossible to control. Fusion’s ever-receding promise suggests caution, but a British company, Tokamak Energy, is increasingly confident it can generate electricity by 2030, ahead of its American rivals. It forecasts ten large (1.5 GWe) power plants a year being built by 2035, and a hundred by 2040. It is a cheeky, private-sector upstart challenging the slow, international, public-sector collaboration on fusion.

The new fusion optimists base their confidence on yttrium barium copper oxide (YBCO), a novel superconducting material that allows smaller, less cold but more powerful magnets. Britain is a world leader in YBCO technology, so it is not impossible that we could see a breakthrough here in the next two decades comparable to Thomas Newcomen’s steam invention of 1712.

Suppose fusion does make the “too cheap to meter” breakthrough that fission failed to make. We could then stop worrying about carbon dioxide, but what would we do with all this energy? We could make as much fresh water as we fancied, through desalination, to water the deserts. We could grow food indoors to release the countryside for nature. We could electrify all transport. We could enable Africa to become as wealthy as America.

A green misery-monger called Paul Ehrlich once wrote that giving cheap, abundant energy to humanity would be like “giving an idiot child a machine gun”. On the contrary, cutting the cost of energy is absolutely central to delivering prosperity and fairness. This is why it is so baffling that Britain keeps pushing up the price of energy to encourage the medieval technologies of wood, wind and water power.

Professor Dieter Helm’s official review of government energy policy last year found that we could have reduced carbon dioxide emissions for far less than the £100 billion already spent on renewables by encouraging a switch to gas. But, as he says, governments are bad at picking winners, while losers are good at picking governments. Meanwhile, Germany, which has spent something like a trillion euros on support for green energy, is now building lots of coal-fired power to keep the lights on.

At huge cost, Germany is learning that you cannot have a cheap, reliable, low-carbon grid without the high EROEI of nuclear. The Energiewende is a historic error. But is there any guarantee governments would suddenly be more rational if fusion came along?

Matt Ridley's Blog

- Matt Ridley's profile

- 2180 followers