Heather Blanton's Blog, page 33

July 25, 2013

Esther Reed — Where June Cleaver Got Her Domestic Goddess Genes?

by Heather Frey Blanton

Esther De Berdt Reed, though born in England, found the cause of liberty trumped ties to homeland and tradition. Perhaps her future husband, American Joseph Reed, had something to do with her fervor. The two met in London in 1763 when he was studying law. True love took its course and they became engaged, yet Reed left to tend to matters in America. The couple endured a five-year separation. Esther clearly knew her mind and her heart.

The two married and moved to Philadelphia around 1770 when the abuses of the crown were just getting rolling. Joseph worked hard and became a prosperous lawyer. His wife threw wonderful soirees that included the likes of General George Washington. After the battles at Lexington and Concord, though, Joseph was called to serve his country. He rose quickly through the ranks, eventually becoming a general himself.

Esther was left at home to raise six children and manage her household. Prepare to feel inadequate, because she was clearly more than a Philadelphia housewife. Esther not only moved her family out of Philadelphia three separate times to avoid British soldiers and Tory mobs, she also dove full tilt into fundraising for the cause. Using her gifts, connections and time as wisely as possible, she started the Ladies of Philadelphia, a group of women focused on raising money for the American soldiers. Initially they thought to give cash to the troops. Washington gently suggested the money be used to buy clothes. But he left the decision up to Esther.

Before Esther’s death in 1780 at the young age of 34, her group raised a whopping $7000 for the Continental Army and then used the money to buy cloth for shirts. Together, the ladies and their servants then sewed 2000 shirts. June Cleaver would be proud of these gals.

Esther gave all and died no less valiantly than a soldier under cannon fire. She knew what kind of a country she wanted her children to grow up in. One without a pompous king taxing them to death and determining their future. Inspired by Esther’s passion, Sarah Franklin stepped up to take her place and had similar success. Esther Reed was the first woman to be called A Daughter of Liberty. Amen, sister.

May 20, 2013

Elizabeth Van Lew — A Daughter of the South With the Spirit of a True Hellion

Reprinted from http://www.americancivilwarstory.com/elizabeth-van-lew.html

(I highly recommend this website!)

Willing to put it on the line for her country and her friends.

Elizabeth Van Lew was born in October of 1818 in Richmond, Virginia. During her childhood, Elizabeth was considered to be the most stubborn of the three Van Lew children. Her parents were John and Eliza Van Lew.

John Van Lew had come to Richmond at the age of sixteen, and by his mid thirties had built a successful hardware business. His new-found wealth made the Van Lew family one of the most prominent in the city.

As a teenager, Elizabeth was sent to a Quaker school for girls in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There, she became convinced that slavery was wrong and should be abolished. She took this belief back to Richmond, where it became her most defining feature.

Upon her fathers death, Elizabeth inherited about 10,000 dollars (roughly equivalent to 200,000 dollars today). She immediately spent all of it buying and freeing relatives of her family’s former slaves.

Elizabeth Van Lew soon a five station relay line by which her messages were quickly carried from her home in Richmond to the Union high command. One popular story concerning her message-line, tells that she would sometimes deliver fresh flowers and a Richmond morning paper directly to General Grant.

She often used her former slaves to carry her messages. Sometimes they would be hidden in a shoe, sometimes sewn into the work of a seamstress, sometimes hidden in a hollowed out egg in a basket of regular eggs. Whatever the case, her messages always got through unmolested.

One of her former slaves was Mary Bowser, a very intelligent young lady whose schooling Miss Van Lew had paid for before the war. Somehow, Mary Bowser managed to get a position as a servant in the Confederate White House.

There she was able to read secret papers, and listen in on important meetings. All the information that she gathered in the home of Confederate President Jefferson Davis was passed, through Miss Van Lew, straight to the Union high command. These ladies were probably the most successful and effective spy team of the Civil War. It is even believed that the two worked together to try to burn down the Confederate White House on one occasion.

During the war, Elizabeth Van Lew was somewhat of an outcast because of her anti-secession, pro-Union positions; but when it became known that she had been a Union spy, she was treated as a complete social pariah. Penniless and nearly destitute, some family and friends of a Union officer whom she had helped during the war heard of her plight. These folks put together an annuity which supported Miss Van Lew for the rest of her life.

April 30, 2013

Mom Rinker — the Little Ol’ Lady Who Spied for Washington

She sat up there at the top.

There is a rock in Philadelphia along the Wissahickon Creek made famous by a little old lady who was one of George Washington’s best spies. No blond bombshell who blinded the British with her shocking good looks, she was merely an innocuous-looking little ol’ lady.

One of the complaints against King George listed in the Declaration of Independence was

“…For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us”

Troops could and often did simply move in and take-over a family’s home. Understandably, this didn’t sit well with the property owners who weren’t in favor of the King’s rule in the first place. Molly “Mom” Rinker was one such dissatisfied English subject willing to fight for her independence. She didn’t sit idly by while British soldiers took over her family’s inn and planned their attacks. An older, matronly woman, who would ever suspect her of being a raging patriot and spy?

No one … and she planned to keep it that way. While soldiers banned the male members of her family from the dining area, Mom was kept at hand so she could wait on the redcoats. She waited on them, all right, and made sure to keep jugs of liquor and ale in the dining room so she had fewer excuses for leaving.

Then this clever little Granny-like lady would pass intelligence to Washington’s men. She was never caught; her identity never revealed. So how did she do it?

Each night after gathering her intelligence, she wrote the information on a small piece of paper and wrapped it around a tiny stone. She then wrapped yarn around the stone until she had a normal, mundane looking ball of yarn. Every day, Mom would go to a lovely little spot along her favorite creek and seat herself on a rock. From this rock, she had a pleasant view of the woods.

She would then subtly drop the ball of yarn and watch it roll down the small cliff. One of Washington’s men would retrieve the note and disappear into the brush. No one was ever the wiser. The British never saw her converse with anyone. Granny sat upon her rock and knitted stockings for her beloved Colonial soldiers. She couldn’t be the spy; had to be someone else.

The British never even searched her basket. Probably wouldn’t have found the messages anyway. Not all spying during the American Revolution required complicated cloak-and-dagger techniques. The beauty of this deception was its simplicity, an idea born of wisdom and experience. Talk about a woman who could truly say, “Mom knows best.”

by Heather Frey Blanton

LIKE ME: https://www.facebook.com/heatherfreyblanton?ref=tn_tnmn

Tweet Me: https://twitter.com/heatherfblanton

April 22, 2013

Sometimes, a Woman Went West … Who Shouldn’t Have … The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Story

by Heather Frey Blanton

LIKE ME: https://www.facebook.com/heatherfreyblanton?ref=tn_tnmn

https://twitter.com/heatherfblanton

Not every woman who helped settle America did so with eager determination. Some did what they had to do and didn’t really think about it. Others, deeply regretted ever leaving home and most likely spent their last breaths cursing the fateful decisions. None of this makes these women any less brave.

Narcissa Whitman, the first white woman to travel west of the Rockies, is sadly, one of the darker stories of settling the country. She started out with good intentions, focused too much on the bad when things didn’t go her way, and ended up dying an ugly death.

Early in 1836, she and her new husband Marcus Whitman left New York to open a mission in Washington state. You’ve got to put the danger and difficulty of this trip into perspective. This was before the 1849 Gold Rush that caused the West to explode with settlers. The land left of the Rockies was populated by Indians and mountain men. Period. Roads were mere trails. There was no rail road, no stagecoach lines, no towns, unless you counted military forts. But Narcissa fell in love with Jesus at the age of 11 and knew he had a plan for her.

She was convinced the Indians needed to know about Jesus and answered God’s call to carry his word into the darkness. With few possessions and an energetic, often insensitive, faith, they arrived at their destination in late September.

For Narcissa, this was really when the hard work began. Her husband, a doctor, had many opportunities to get out and about for medical calls, but she stayed mostly at the mission. The Cayuse Indians were not very receptive to the Whitman’s teachings or way of life. Constant misunderstandings occurred because of issues with cleanliness, privacy, and ownership of property.

Eventually the couple, disillusioned with the Indians, turned more towards the trappers and immigrants passing through. Still, due to language and faith barriers, Narcissa was lonely. Things only went from bad to worse for her when her daughter, two-year-old Clarissa, drowned in the Walla-Walla River.

Tensions between the Whitmans and the Cayuse continued to rise as thousands of settlers poured into Washington and the mission-turned-trading-post played host to them. Over a decade, the Cayuse saw their land and way of life disappearing because of this onslaught of settlers. Marcus had several physical altercations with warriors in the tribe who insisted the Whitman’s close the post and leave.

In the fall of 1847, a wagon train arrived with over five thousand immigrants. Along with their hopes and dreams of a brighter future, these settlers also brought with them measles. Few of the Cayuse had any resistance to the disease and dropped like flies. Rumors circulated that Dr. Whitman was causing the deaths. The Indians attacked. Along with her husband and fourteen other people, Narcissa died in the mud just outside her door.

An inglorious end to a noble, though misguided, effort. Still, Narcissa had tried. She dealt with things the best way her whiney nature would allow. I respect her efforts, but I’m glad I’m not her descendant.

April 1, 2013

Dorothy Sinkler Richardson — Did She Have the Last Laugh Saving the Swamp Fox?

by Heather Frey Blanton

LIKE ME: https://www.facebook.com/heatherfreyblanton?ref=tn_tnmn

https://twitter.com/heatherfblanton

All that remains of a life well lived.

As I have often said, I discover the most fascinating things about the women who built this country by reading between the lines.

Case in point, Dorothy Sinkler Richardson. You’ve probably never heard of her unless you delve deep into South Carolina history. But you’ll recognize some of the names in her story.

Dorothy was the second wife of General Richard Richardson. Both were ardent patriots. Richardson, however, died in British custody after the fall of Charleston in 1780. No shrinking violet, Dorothy kept her head about her and ran her home. She also continued to support the cause of liberty. She seemed to have at least a passing acquaintance with Frances Marion, the Swamp Fox.

Unfortunately for Dorothy, Banistre Tarleton opted to bivouac in her home in 1781. He made no secret he was after Marion and felt that he and his men were close. Knowing what was at risk, as Tarleton’s reputation for butchery was well-documented, she still opted to send her 10-year-old son James to warn Marion. The boy succeeded, Marion changed directions, and Tarleton got a very angry.

He forced Dorothy to prepare his dinner and then serve him. Several accounts also report that he had her husband’s body dug up just so he could see a “real” American general (I certainly wouldn’t put this past him). And if all this wasn’t enough, Tarleton then burned her home to the ground.

Banistre Tarleton may have left Dorothy’s farm that night giddy and giggling with great satisfaction. It was quite premature, though typical of his arrogance. He destroyed Dorothy’s home. He did not destroy her spirit. They say the proof of a life well-lived is in your children. She raised two boys who became governors of South Carolina.

Her son James had the following inscription carved onto her tombstone:

Relict [widow] of Gen. Richard Richardson Who died July 1793 Aged 56 years

She was pious & exemplary, distinguished in mind & manners and eminently discernible in the highest societies in which she associated. This marble which designates the place where her remains rest is erected to her memory by her eldest son James B. Richardson Who early bereft of paternal care feels that he is indebted to her maternal care & attention, to her vigorous & preserving mind of firmness & determination surpassing description and to her vigilant and enlightened instructions for being all that he is in life.

Respect the lace. She earned it.

March 11, 2013

She’s Black, She’s a Woman and She’s Old! Are You Blind? Yep…

by Heather Frey Blanton

LIKE ME: https://www.facebook.com/heatherfreyblanton?ref=tn_tnmn

https://twitter.com/heatherfblanton

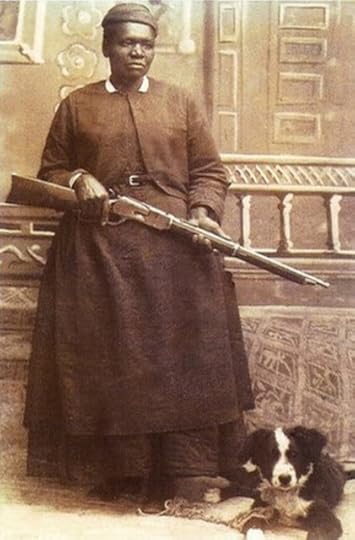

Mary Fields — All six feet of her!

Being a woman out west at the turn-of-the-century would have been hard enough. Can you imagine being a black woman? Well, for Mary Fields, it was all in a day’s work.

“Stagecoach” Mary Fields was a black slave born in TN probably around 1812 or so. She was taken into Judge Dunn’s family and served as a nanny and house maid, and remained with the family, even after emancipation. During her growing up years, she became friends with Dunn’s daughter Dolly. Dolly, a gentle soul, joined a nunnery and shortly after transferred to Saint Peter’s Mission in Cascade, MT. She quickly discovered that the mission, a school for Native American girls, was in a magnificent state of disrepair.

Sister Amadeus (or, the daughter formerly known as Dolly) just about killed herself trying to get the place cleaned up, to the point she contracted pneumonia and fell deathly ill. She contacted Mary at this point and asked if she would like to come west and help out for a bit. Mary must have been a sight to behold walking around the school. Over six feet tall, weighing in at a lean two hundred pounds, wearing pistols on both hips, this woman was big and very black. And she liked to work. She nursed her friend back to health and then took on the mission, literally. An indomitable attitude coupled with her skill with a hammer and Mary was promoted to foreman of the place in pretty short order.

Not all the men on the grounds crew were OK with this and one mouthy gentleman started a fight. Not only did a bullet windup tearing daylight through the bishop’s drawers (on the wash line), some folks just didn’t care for Mary’s less than ladylike language and her fondness of alcohol. The bishop forced Sister Amadeus to fire her old friend.

After a short-lived attempt at running a restaurant, Mary applied for a job with the US Postal Service delivering mail at the age of 60. The USPS was looking for one qualification: the fastest time in hitching up a team of horses. Consequently, Mary became the first black woman hired by the USPS and only the second female in general.

God love her, Mary’s belligerent attitude, never-say-die determination, and willingness to fight at a drop of hat served her well in this job. She gained an unequalled reputation for delivering the mail. Literally, sleet, snow, ice, blizzards, bandits, it didn’t matter. If the horses couldn’t make the trek, she strapped on snowshoes and kept on trucking. In between, she spent a lot of time at the local saloon and developed quite the reputation for fisticuffs. And what girl doesn’t enjoy a pinch of Copenhagen between the cheek and gum after a tough fight?

Mary retired from the post office at the age of 70 and the nuns at the mission helped her open a laundry, which she ran until her death in 1914. This woman was so loved by the folks of Cascade, they closed the schools to celebrate her birthdays.

Race, gender, age, all barriers Mary busted wide open and the citizens of Cascade were smart enough to look past. Now that’s what I call “respecting the lace.”

March 6, 2013

Mary Katherine Goddard — Daughter of the Revolution and Forerunner to Lois Lane?

by Heather Frey Blanton

https://www.facebook.com/heatherfreyblanton?ref=tn_tnmn

https://twitter.com/heatherfblanton

Sometimes, the pen is mightier than the sword.

Some women during the Revolutionary War did amazingly brave things. These women warriors rose to the level of their challenges and met them head on. But not every woman took a rifle in hand to make a fight. Mary Katherine Goddard, arguably the first female journalist of the Revolutionary War, fought with ink and paper.

In 1762, 24-year-old Mary Katherine moved with her younger brother and mother to Rhode Island. Brother William had finished an apprenticeship in printing and planned on starting a print shop and newspaper. Together the family published the Providence Gazette. Mary Katherine was a quick study, though. After William established an additional shop and newspaper in Philadelphia, he turned that store over to his sister in 1764.

Philadelphia was a hot-bed of Colonial rebellion. Mary Katherine reported it with a fair and balanced approach, despite the fact that her brother was rabidly anti-British. He was repeatedly jailed for outbursts and printed tirades against the crown. In 1774, Mary Katherine took over her brother’s paper in Baltimore while he attended to other interests, including trying to set up a postal system in opposition to the official British mail service.

In January of 1777, Mary Katherine courageously used her press to print copies of the Declaration of Independence, only the second publisher to do so and the first to print all the names of the signatories. Considering the times, this was arguably a treasonous act. She was also the first female appointed as a postmaster in Colonial America. She served in that capacity for the city of Baltimore from 1775 to 1789. It’s worth mentioning that Mary Katherine never missed an edition of the Maryland Journal from 1775 to 1784. In the midst of war, when lesser papers folded or went into hiding, the city’s government switched hands, and battles raged, she kept the presses rolling, so to speak.

It wasn’t all daisies and sunshine for May Katherine, though. In 1784, her name disappeared from the masthead of the Maryland Journal, and in 1789 she was forced to step down from her position as Postmaster (despite a petition signed by over 200 Baltimore merchants to keep her). The issues? Her brother was jealous of her success (he hadn’t accomplished a thing in his life that Mary Katherine didn’t bring about), and she was a woman without the appropriate friends in high places. Infuriating, yes, but I suspect Mary Katherine did all right. She ran her own bookstore in Baltimore till her death in 1816. Nobody really remembers her brother or the man who replaced her as Postmaster. There’s some justice in that.

February 26, 2013

Margaret Corbin — Was She the Woman Who Gave Cornwallis Nightmares?

by Heather Frey Blanton

https://www.facebook.com/heatherfreyblanton

https://twitter.com/heatherfblanton

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. If that’s true, then Margaret Corbin was one of the strongest women of the Revolutionary War.

Her life started out with a fairly bad omen. Around the time of her fifth or so birthday, she and her brother went to visit her uncle. While the two were gone, the family farm in Pennsylvania was attacked by Indians. Her father was scalped and killed. Her mother was taken captive and disappeared into the pages of history.

Margaret trudged on however and developed a keen dislike for King George. In 1775 she married John Corbin. When he enlisted in the Continental Army, Margaret went along, as women often did, to sew and cook. Not being stupid, however, they also picked up on military drills, routines and protocol.

This would explain why women were able to jump into battles alongside their husbands and actually make valued contributions. So, like Molly Pitcher, when Margaret and John went into their first battle (the Battle of Fort Washington), she was ready to assist. John was a matross (he loaded the canon) and when his partner was killed, he took his position. Unflinchingly, Margaret then took on the duty of matross. Shortly thereafter, however, John was killed. Unbroken, defiant, and completely alone, Margaret “manned” the canon herself. She loaded and fired the thing repeatedly with deadly accuracy! Hers was the last canon firing, which eventually made her an easy target.

Margaret was discovered after the battle alive but in critical condition. She had three musket balls in her, her chest and jaw were damaged by grapeshot and her left arm was quite literally hanging by shreds of skin. Surely this is the woman who gave Lord Cornwallis nightmares!

An amputee, she continued to serve in the cause of Liberty in the invalid regiment at Westpoint. She even remarried, but her second husband passed away a year later. On her own, Margaret wasn’t able to stay well-coiffed due to her injuries and therefore alienated a lot of folks. Not to mention, she was a bit rough and unrefined; given to drinking (a lot) and smoking. The Philadelphia Society of Women thought to erect a statue to her until they met her and then they called off the whole idea. I wonder how many of them ever jumped behind a canon?

But good men in the military did not forget Margaret and eventually, after spending many years destitute and poor, she became the first woman to receive a military pension. Eventually she was even reburied at West Point with full military honors.

Dear Philadelphia Society of Women, it just goes to show that well-behaved women rarely make history. Respect the lace.

February 11, 2013

Why Won’t You be a Good Girl, Ethel? Just Settle Down and Get Married to that Sheepherder!

by Heather Frey Blanton

https://www.facebook.com/heatherfreyblanton

https://twitter.com/heatherfblanton

Again, I am intrigued to read between the lines. A city girl leaves Denver, degree in hand, to accept a job as a teacher on a Wyoming ranch. Her classroom consists of seven students. During her school year, she meets her future husband, a handsome, ambitious sheepherder. It takes this stubborn Scotsman five years and dozens of sappy letters to convince Ethel to accept his proposal. What was she waiting on?

Born into a relatively wealthy family, Ethel was a fearless young thing with a big heart. She spent a summer volunteering in the slums of New York, if that tells you anything. In 1905 she finished at Wellesly and took a job teaching the children on the Red Bluff Ranch in Wyoming. Her letters indicate she fell madly in love with the place and its people, but not so much with John Love. Oh, she liked him well enough and appreciated the fact that he made the eleven-hour ride to see her several times during the school year. Ethel, though, apparently wasn’t ready to settle down. She had, you know, places to go, people to see, things to learn. Or was she simply afraid marriage might mean her life would pass into obscurity?

At the end of that first teaching job, she enrolled in the University of Colorado to obtain a master’s in literature. That’s when the letters started arriving. Lots of them. And John made no secret of why he was writing. Ethel needed to be his wife and he would wait for her. No matter how long it took. Unless and until, she married another.

When Ethel received her degree in 1907, she took a job in Wisconsin, again as a teacher. Still the letters followed. And she answered, often with an apology that she shouldn’t. She didn’t want to give him false hope, after all. Once she even scolded him for closing his letter with “ever yours,” instead of the customary “sincerely yours.” Yet, Ethel did not entwine her life with any other men. She didn’t often attend dances or parties. Strange girl. It’s almost as if she was the female version of George Bailey. Perhaps restless, she moved back to Colorado in 1908 and continued her work, but where was her heart?

Ethel spoke four languages, enjoyed writing, especially poetry, even staged theatrical productions. But that sheepherder, who buy now was doing pretty well for himself, wouldn’t give her any peace. Finally, this fiercely independent American girl caved. The two were married in 1910.

Maybe John just had to prove he could respect the lace.