Hugh Howey's Blog, page 27

October 27, 2014

Two Important Publishing Facts Everyone Gets Wrong

Almost everything being said about publishing today is predicated on two facts that are dead wrong. The first is that publishers are somehow being hurt by ebook sales. The second is that independent bookstores are being crushed. The opposite is true in both cases, and without understanding this, most of what everyone says about publishing is complete bollocks.

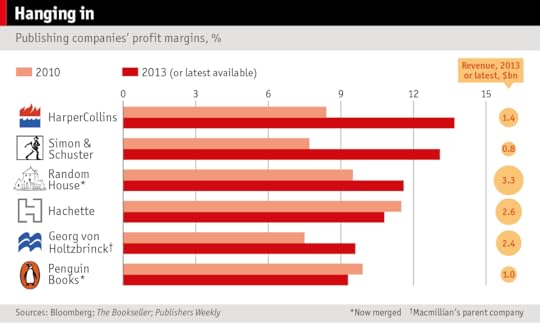

Let’s take the health of publishers first. Below you will see that profit margins at the major publishers are either flat or improving. For three of the top publishers, margins have improved quite a bit:

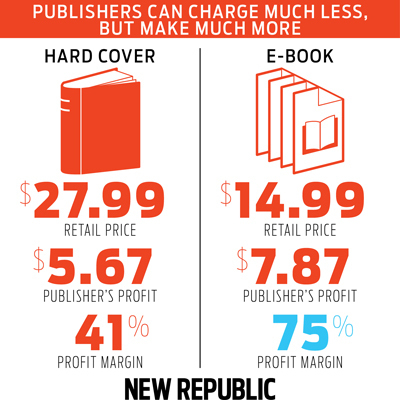

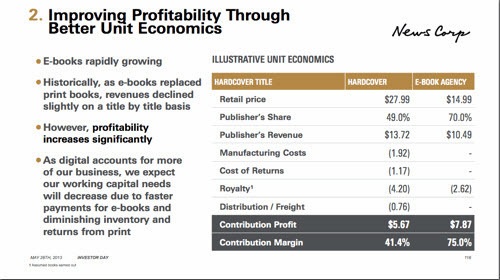

Here we can see why. Margins on ebooks are much higher than the previous cash-cow, hardbacks:

We even have a slide from Harper Collins to investors showing a breakdown of these ebook profits compared to hardback profits:

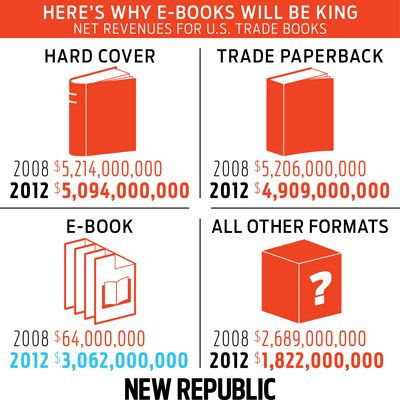

So while revenue is down in other formats, the explosion of revenue in ebooks more than makes up for it:

Nearly three BILLION dollars of new revenue, which is more than double the $1.2 billion lost elsewhere.

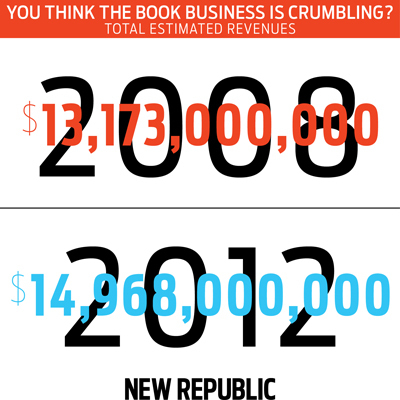

Overall revenue is therefore up:

If ebooks are doing so well, bookstores must be going bust, right?

Only some of them. The large big-box discounters, who overbuilt in the retail boom of the 80s and 90s, are indeed suffering. Meanwhile, the independent bookstores that those big-box discounters nearly pushed into extinction are roaring back. While over 1,000 stores closed during the B&N and Borders expansion leading up to 2007, since 2009, the number of indie bookstores has risen over 20%. And sales are up over 8 percent year on year the past three years, which is far more growth than the overall book business.

What happened? I liken it to the rescue of Yellowstone National Park when the Canadian Wolf was reintroduced to that ecosystem. An overpopulation of deer was leading to the destruction of saplings due to bucks rubbing their antlers and destroying trees. Fewer trees meant more erosion. The landscape was changing, and species downstream were being pushed to the brink. Bringing the wolf back restored balance and saved those downstream species.

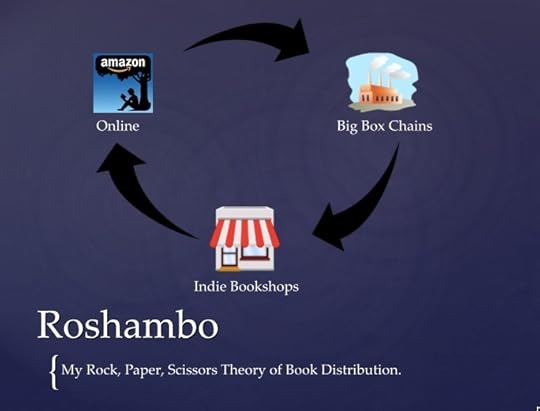

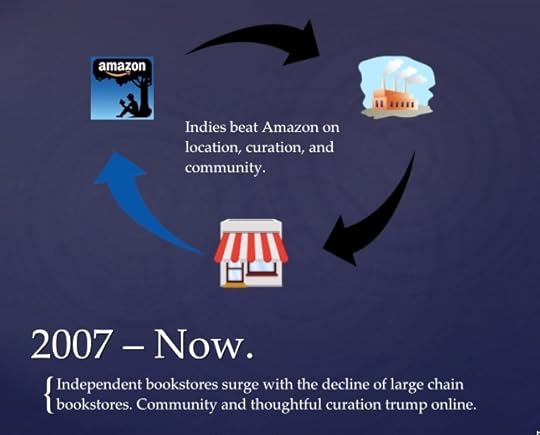

At an O’reilly Publishing event this year, I presented this as my Roshambo Theory of Book Distribution. It looks like this:

Each of the three entities dominate their clockwise neighbor in some crucial aspect while being vulnerable to the neighbor on the other side in an equally important aspect.

Let’s start with the big-box discounters, which came into being at the same time other retail channels were expanding (like WalMart, Target, Home Depot, Lowe’s). With far superior selection and prices, they drove out their competition, which had smaller footprints and higher prices:

Over 1,000 indies closed during this time. Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan made a movie that was more about this than about AOL, despite the title (You’ve Got Mail) coming from the latter.

In the mid to late 90s, retail began moving online. Suddenly, the biggest strength of the big boxes — price and selection — paled before the power of “everything stores.” Borders bookstores went under in 2011. B&N has been showing quarterly losses, even as it closes stores and shrinks shelf space within existing stores. The advantage in one direction became a serious weakness in the other, as the big boxes couldn’t compete with online retailers:

Independent bookstores, meanwhile, have advantages that online retailers don’t. Physical location, immediacy, hand-selected curation, a focus on local topics and authors, community events, fresh coffee, browsing, personal help, and so on. These are all things that the big box discounters did well enough that their advantage in selection and price was able to dominate. But online retailers are too weak in these areas to push out independents:

At first, it appears that each of the three parties has an advantage that trumps one other. The problem here is that big box discounters don’t excel enough in either area (physical space or price/selection) to beat the others. In fact, what looks to be a balanced ecosystem between three retail paths will probably devolve into simply online and independent booksellers (the latter will form regional chains). There are enough people who will support independents and pay full price and enough who will shop online when they know what they need that the two will coexist.

So feel bad for hardbacks and paperbacks, but don’t feel bad for stories, storytellers, or readers. The latter trio is doing just fine. As are publishers.

And feel bad for big-box discounters if you want, but remember that they were far worse for mom-and-pop stores than online retail has been. In fact, since the advent of online retail, we’ve seen their numbers and their revenues rebound.

You can’t argue with either fact. Publishers and small bookshops are, on the whole, doing better now than they were in 2007, when the Kindle launched. That’s irrefutable. And so any conversation about the effect online retail and ebooks are having on the industry need to begin right here, rather than assume the opposite is true and then spread fear and doubt to generate clicks.

October 26, 2014

A Shift Away from Indies?

Ars has a great article up on how smaller musical acts are being affected by streaming and subscription models, and how Apple used to be able to give these acts an enormous boost — but no longer seems to have that power (or interest).

It’s a must-read for authors or anyone interested in entertainment and digital disintermediation. Could the same thing be around the corner for indie authors? Will income diminish as all-you-can-read subscription services mature? Will breakouts be more rare as top authors vie for promo spots that used to be about the discovery of new art but are slowly becoming more useful as advertising for competing platforms? I think this last fear is a valid one, and it would be a detriment to readers as well as upcoming writers.

There’s also mention of how spreading yourself too thin as an artist by doing promos everywhere is not as powerful as the directed energy of a single major player. Could it be that a more competitive market for the consumption of art diminishes the cultural penetration of that art? As iTunes lost market share, did music lose some significance in our daily habits? Would video do the same if YouTube lost market share to dozens of competitors? What effect does dilution of platform have on buzz and word-of-mouth?

One other potential pitfall for authors is hinted at in the article: Devices like iPods that used to be about music have morphed into iPhone swiss army knives where tunes are one app among many. Similarly, I see the threat of people buying tablets instead of dedicated e-readers (the latter is far superior for reading and has fewer distractions). If you are a book-lover or an author, it’s a good idea to rave about your e-reader and maybe let people you know borrow the device and give it a try.

The article is long but seriously worth the read. I’ve learned a lot about the publishing industry by watching the music industry. We seem to lag behind them a few years in many developments. If possible, let’s learn from their mistakes instead of resigning ourselves to repeating them.

October 23, 2014

Live-Blogging from NINC

My first NINC conference. What a brilliant bunch of authors. Thought I’d make some notes and drop some ideas as I have them (so this post will keep updating).

Porter Anderson asks a panel of experts if low prices are devaluing books. Can low prices really devalue literature? If so, what about the gift that are public libraries? And another thought: If price can devalue literature, does paying authors miserly royalty rates devalue writers and writing? Why is that never a focus?

A BookBub representative says “price is a marketing tool.” I absolutely agree. And I think the consternation about low prices comes from those who see these titles as an intrusion on their own profitability. I don’t see this threat. New authors need to level the playing field and win over their own readership. I think it’s the difference in seeing book-buying as a zero-sum game or an additive game. I subscribe to the latter view.

I’m not convinced readers are so homogenous. Some are bargain-shoppers. Some are more prone to experimenting with unknown authors. Some will pay a premium for a known author or a current bestseller. I look at the auto market as an example. Some shoppers are only looking for a used car; some are looking for a new car; some are looking to lease. Confusing these shoppers as the same people is a huge mistake publishers and authors often make.

Most animated exchange thus far: A publisher executive in the audience pitches the advantages of working with them, when Brenna Aubrey says “Just get rid of your non-compete clauses.” A representative of that publisher (who is on the panel) says, “We don’t use non-competes.” And then the executive from the same house had to respond: “Actually, we do.” And then: “And it’s for the author’s benefit.” Got a bit raucous.

October 21, 2014

Speculation on the Amazon – Simon & Schuster Deal

Whew. As a Simon & Schuster author, I have to say I’m relieved to see how quickly my publisher struck a deal with Amazon. According to several sources, the negotiations took just a few weeks and the agreement was reached with months left on the current contract. It’s a multiple-year deal, and both sides sound pleased with the results. Simon & Schuster retains the rights to set prices, and Amazon retains the ability to discount.

Everyone is speculating on the finer points of the deal and wondering why Hachette can’t come to terms with Amazon. Hints abound. In fact, the terms Amazon is seeking have been staring every self-published author in the face for years. We can even catch glimmers of confirmation in this Simon & Schuster deal.

Engadget reports that Simon & Schuster now has “a financial incentive to drop prices.”

The New York Times quotes S&S as saying that “with some limited exceptions,” the contract gives S&S the ability to dictate prices.

A financial incentive to drop prices. Limits on S&S’s ability to dictate prices. What does this deal entail?

Some commentators are hailing the deal as a return to Agency pricing, but I wonder if these are the same commentators who claim that self-published KDP authors employ Agency pricing?

Guess what? We don’t.

Our agreement with Amazon is something more like Incentivized Agency. If we set our prices between $2.99 and $9.99, we get 70%. If we set our prices outside that range, our split drops to 35%. According to our EULA, Amazon retains the right to discount our ebooks as it sees fit.

What does this mean? It means if we price our ebooks at $14.99, Amazon has plenty of meat left on the bone to discount our ebooks back down to $9.99. The customer gets a good price, and Amazon still makes a profit. That is, we the authors are punished for jacking up the prices.

Who wants to bet that this is what Amazon wants from publishers? The KDP agreement is what Amazon offers with practically zero negotiations back and forth. We should take it as their ideal agreement. The publisher (in this case, individual self-published authors) set the price. But it’s within a range that Amazon specifies, or else we lose margin.

So when Hachette cried foul back in May that Amazon was after a percentage of profits, that’s because they saw Amazon offering perhaps only 50% on ebooks priced above $9.99. Amazon has been right to say that the negotiations are about price, and Hachette has been right to say that the negotiations are about margin. That’s because margin is to be determined by price, just as it is for KDP authors.

Simon & Schuster entered into these negotiations with a greater awareness of the power of pricing. Surely they watched John Green’s THE FAULT IN OUR STARS tear up the charts at $4.99 (now higher). Or how about the fantastic HOW WE GOT TO NOW by Steven Johnson, which is new in hardback but selling the Kindle edition at $4.99? This is a Penguin book, and it’s in the top 500 at Amazon (great book, btw).

There’s another advantage to this deal for Simon & Schuster. Pressure for higher ebook prices comes from print retailers, who don’t want to be undercut. Publishers aren’t stupid; they know they can sell more ebooks at a lower price and make money doing so, but they worry about harming existing partnerships. S&S can now price some ebooks high, knowing that Amazon has room to discount, and they can go to the buyers at their major accounts with the digital list price to show their support. That is, the blame for the eventual lower sale price will fall on Amazon, which brick and mortar outlets already loathe, and S&S gets to look like a champion. Meanwhile, they are giving up a percentage of margin to help Amazon discount. Everyone wins. Especially the customer.

There isn’t a sliver of a leak about this deal that doesn’t fit the model of Incentivized Agency. S&S sets prices; Amazon can discount; there are “financial incentives to drop prices.”

The nail in the coffin comes from New York Times’ David Streitfeld. As a reporter with close ties to Hachette and its authors, Streitfeld looks for any opportunity to goad Amazon and praise the Big Five publishers. So much so that his own paper called him out for his bias. So what can we learn from his coverage of this agreement? A lot, it turns out. Pressing sources to confirm that Simon & Schuster won a major victory for all of publishers, Streitfeld no doubt wanted to hear that S&S maintained its share of income for all books sold. Any hint of this, and you can be sure he would report it. Instead, we get this sheepish admission: “While the publisher did not explicitly say the deal maintained its own share of income, a source with knowledge of the negotiations who was not authorized to speak publicly pronounced the publisher happy with the terms.”

My guess is that Streitfeld learned the split is dependent on price, but he doesn’t want to be the one to break that news. Eventually, it’ll be public knowledge that Amazon pays a higher rate when wholesalers provide ebooks at a sane price. And people will be shocked. Except for self-published authors, who have been pressured by Amazon to keep ebook prices in a reasonable middle range for years.

The one statement we have from Amazon about this deal claims: “Importantly, the agreement specifically creates a financial incentive for Simon & Schuster to deliver lower prices for readers.”

So there you have it. Congrats to both parties for putting this together.

October 20, 2014

October 2014 Author Earnings Report

The latest Author Earnings report is up. This is our first look at the effects of Kindle Unlimited — we’ll be diving in further in coming months. I wish our conclusions could be more . . . conclusive. To me, weighing all the benefits of KDP Select against the minus of exclusivity, my thinking is that KDP Select is great for those starting out and those selling at the very highest levels. For those in the middle, who might be getting traction on other outlets, the increase in sales does not seem to outweigh the percentage of the market given up.

KDP Select is not an all-or-nothing program, of course. Perhaps it is the ideal place to launch a new series or to give underperforming works a boost. Put them in for 90 days or 180 days, and then branch out once they take hold. It could also be that an expanded readership outweighs cold financial calculations for some authors. The best advice may be to experiment.

I’ve been able to experiment with KU without the exclusivity requirement. It’s not a permanent exclusion, and I’ve been leaning toward exclusivity and staying in KU once it expires. I’m now leaning the other way. Even with the potential of All-Star bonuses, I’m not keen on a system that rewards the top and bottom but leaves out the middle. What I’d love to see is for Amazon to drop exclusivity as a goal. They already have (by far) the best marketplace for discovering ebooks and purchasing them. They have the best lineup of devices (having seen the newest e-ink display). They have one of the best upload and stat dashboards (after having revamped the latter).

So why not make KU elective for all authors? Why not set the pay scale by page rather than reward shorter length works? Compete for readers in all the other ways that Amazon excels (customer service, one-click, search, also-boughts, recommendations, reviews, etc.) and let authors publish their works far and wide. I have a feeling most authors would continue to share Amazon links by default. I have a feeling Amazon would be just fine and continue to dominate in this space. And everyone else would be a little better off.

October 19, 2014

Plan Ahead for Happiness

This one’s for high school students. With a bit of planning, you can reap enormous rewards in mental well-being that will reverberate for decades. The steps are simple:

Purchase a pair of jeans that are three to four sizes too large.

Wear said jeans around school for a few weeks (suspenders may be required).

Upon graduation, pack away said jeans with other mementos (yearbooks, diploma).

Twenty years later — on the verge of turning 40 — rediscover said jeans, try them on, and marvel at the fit!

Brag to spouse.

You’re welcome.

October 16, 2014

Big Media in Support of Amazon

Just a week after the New York Times called for more balanced coverage of Amazon’s book business, the call seems to have been taken up by those across the media. One piece from Slate hits some great points on why Amazon is actually a force for good. The piece begins by making light of predictions about what Amazon will do with its market dominance at some point down the road. On what Amazon decides to do with its vast earnings, you have this:

Instead of rigging the retail business in its favor by fattening its margins and exploiting its dominant position in a handful of niches, it is so cutthroat that it sometimes appears to be cutting its own throat, as evidenced by the fact that the company loses a boatload of money.

Bezos is, for whatever reason, less interested in goosing Amazon’s stock price than in building new fulfillment centers, investing in new technologies, and doing all kinds of other things that involve more actual engineering than financial engineering.

I love that last bit (emphasis mine).

More from Slate:

But what about the incentive to engage in the kind of complex coordination that creates enormous value, that raises productivity and delivers lowers prices, that can’t actually be patented? When we decide that Amazon is just a little too innovative and a little too tough, what is the message we’re sending to the next entrepreneur who is debating whether to take on the thorniest challenges?

… having the government step in and squash Amazon before it actually uses its (supposed) pricing power to screw consumers will likely yield less innovative entrepreneurship. The only people who will win in this scenario are the mostly wealthy people who own shares in lazily managed companies. Hurray.

And:

In sector after sector—banking, broadband, and utilities come to mind—large incumbent firms have found new ways to protect themselves from competition, whether through coziness with regulators of sweetheart subsidy deals with politicians on the make to a pathetic lack of imagination among entrepreneurs who refuse to take on the toughest challenges. The sectors that Amazon takes on are the big exception. Instead of damning Amazon, we need to be asking why we don’t have more companies like it.

Completely agree. And I did so before I made a living as a writer. The first time I partnered with Amazon was as the assistant manager at an independent bookstore. Purchasing cheap, used, out-of-print books and new hardbacks at the same discount as I could get from a publisher (but in two days rather than two weeks) improved our bottom line. And Amazon put Waldenbooks out of business in our town and made B&N reconsider opening a location there. Amazon may be partly responsible for the surge independent bookstores are seeing, both in number and in revenue.

Slate’s not the only media outlet defending Amazon.

Here’s Vox pointing out that Amazon isn’t a Monopoly.

Here’s an op-ed at The Boston Globe in defense of Jeff Bezos.

Here’s the Washington Post making a lot of sense.

Even the New York Times got in on the fair coverage with this op-ed, which read more like reportage.

Fascinating. Maybe we really are all starting to come together on this.

Don’t worry. I’m just writing.

Someone explain this to me:

It’s 1 time out of 100 that I write in public (usually by necessity, not by choice).

It’s 1 time out of 100 that I write a scene that makes me cry (again, no stopping it).

It’s 100 out of 100 times that these two overlap. Why the hell?

I’ve had stewardesses (twice) ask me if I’m okay. Another time in an airport waiting at the gate. And this morning at breakfast (a really nice guy this time, who seemed willing to discuss my problems or give me a lift or whatever I needed).

What’s weird is that I never tell these nice people what I’m doing. People have real problems to cry about, and all I could possibly say is: “Don’t worry. I’m just writing.”

Have you had this experience? I’m sure I’m not alone in this.

October 15, 2014

Barbara Freethy and Ingram Join Forces

This is some seriously awesome news. Bigger than a print-only publishing deal if you ask me. Barbara Freethy, who is likely the top-selling modern self-published author around, is working with Ingram to have her books distributed to major retailers.

She retains the rights. Ingram makes their wholesale fee. Barbara keeps the rest. Bookstores get more great content. Readers have access to one of today’s hottest selling authors. Everyone wins.

Kudos to Ingram for putting this together. This removes one of the last few barriers for self-published authors, and that’s print distribution to brick and mortar stores. For other bestselling self-published authors, it’ll mean another option other than selling off all rights to a work, since publishers have been loathe to sign more print-only deals. And it should help bookstores, who didn’t have access to some of the bestselling works around (Barbara has written 19 New York Times bestsellers, including titles that hit #1 on the list!)

Congratulations, Barbara! Couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more hardworking person. Check out Barbara’s website here to learn more about her works.

October 14, 2014

Group Hug

You want to see progress? Take note that the regular attackers of self-publishing as a career choice have altered their aim and are now just going after those who dare to voice their support of self-publishing. Amazon is their number one target, of course, as the top supporter of the self-publishing path. And anyone who defends Amazon—or who argues that self-publishing is just as viable as (if not superior to) traditional publishing—is also a target.

What you don’t see anymore is anyone daring to argue against the substance of pro self-publishing points. Remember the old attacks and stigmas? They used to be:

1) No one sells books by self-publishing. (Often stated as: The average self-published author only sells X books in their lifetime.)

This is rarely trotted out now that dozens of authors have sold millions of titles, hundreds have sold hundreds of thousands of titles, and thousands of authors have sold many thousands of titles. Do all self-published authors have wild success? Of course not. But only 1% of those who submit to agents get published at all. This is finally sinking in, and enough self-published authors have had enough success to put an end to this canard.

2) No one makes money self-publishing.

Difficult to distinguish from attack #1, and going away for the exact same reasons. The truth is that 99% of those who are determined to go the traditional route make zero dollars. And of the 1% who get through the gates, the vast majority of those never make a full-time living with their writing. Where we may have had 300-400 fiction writers earning a living just seven years ago, the number today is likely ten or twenty times that amount, all because of the disintermediation of publishing.

3) It will end your writing career if you self-publish.

Actually, it’s just as likely to start your writing career. A friend of mine just sold his self-published book to a Big 5 publisher for several hundred thousand dollars. It may have been true at one time that publishers only looked at material if it had never been published anywhere else before, but that was laid to rest a long time ago. The stigma is gone within publishing houses. 50 Shades of Grey selling a bazillion copies changed all that. Everyone is looking for the next hit, whether from YouTube stars, Twitter feeds, blogs, or Redditors.

4) Self-published books are inferior in quality.

Hard to keep touting this in light of 1, 2, and 3. Not only are self-published works selling well and earning their authors more on ebook sales than the entirety of the Big 5 combined, but the works are being snatched up and released by major publishers with very little editing.

To compare the entirety of self-published works with only the top 1% of curated manuscripts sent in to agents is a fallacious comparison. In both groups, we have all the works being submitted by hopeful authors along two possible paths. Which group has the higher quality? An even comparison by looking at the bestseller lists on Amazon (ie: letting the reader vote) shows a dead heat.

Also: Snooki.

5) Traditional publishers offer much more to the author.

This one is hard to say with a straight face anymore. Publishers take 82.5% and offer less editing, fewer promotion dollars, fewer book tours, less shelf space, and they take your rights for your lifetime plus another 70 years. Or you can pay freelancers, own your work forever, and keep 70% of the list price.

6) Self-publishing means less distribution.

This one went the way of the dodo when publishers like Simon & Schuster displayed an inability to distribute their works through B&N due to contract disputes. Or the recent dereliction of duty displayed by Hachette, which is destroying the careers of its authors by being unable to come to terms with Amazon.

Borders is gone and B&N is closing hundreds of stores. Independent bookstores are taking up some of that slack with real growth, but 50% of print book sales have moved online to Amazon, and self-published authors have just as much access to that print market as anyone else. And with fiction ebooks set to overtake print, the balance shifts even further. Would you rather have six months spine out in dwindling bookstores, or your entire lifetime to sell your ebooks at a price low enough to actually entice readers?

Price control is part and parcel of distribution. Who in their right mind would give up that power (and the 70% payout) to take their chances on whether or not the publisher they sign with is willing to do business with the #1 bookseller in the land? Plus: have their debut ebook priced at $14.99?

All of the above and more were standard attacks just a year ago. Self-published authors were 3rd rate cattle. Our works were a spewing volcano of shit. Publishing execs blogged about their desire to see two retail channels so we could be placed in a ghetto. Article after article on Salon painted a dim view of self-publishing as a viable option for writers.

But what people like Joe Konrath have been saying for ages is that the economic advantages of self-publishing were too great and that the truth of this would eventually make itself obvious. Now that it has become obvious, the attacks have shifted to the ad hominem variety. People denigrate Jeff Bezos’s character instead of pointing out the options Amazon opens up to the hopeful artist. Salon.com writes a hit piece accusing me of destroying book culture (and does so with misattributed quotes) instead of pointing out anything wrong with what I’ve said about the positives of self-publishing.

I see all of this as progress. Enormous progress. The substance of our points are now unassailable. All that’s left is for those who want to keep the gatekeepers in place to tear us down and attack us personally. Ghandi said:

“First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they attack you, then you win.”

Just three years ago, I couldn’t get anyone to write about what was happening with self-published authors, and it was an enormous story even then. A hidden world, ignored.

Next came the cattle put-downs and the spewing shit attacks. The mockery.

We are now clearly at the attack phase.

Which makes me think it’s time to back off a bit on the arguments for self-publishing. Most open-minded authors must now understand that they have options, and what those options are. The only thing about Ghandi’s quote that doesn’t apply to the stigmatization of self-publishing is the idea of “winning.” There’s no need to come out on top here. The whole point is to have equal access and equal respect, and self-publishing platforms have granted the former while readers have granted us the latter.

It’s over. We can coexist now. People can publish however they want, with opportunities for moving back and forth from one path to the other. And publishers are going to have to continue to sweeten their offerings to lure authors over to their side, while self-published authors will have to continue to up their game to sway readers to their works. The former will probably lower prices while the latter raises them. We’ll meet somewhere in the middle. Will a group hug be too much to ask for? I hope not.