Hugh Howey's Blog, page 26

November 16, 2014

Forecast for Tomorrow: Partly Cloudy

She’s here! She’s almost here!

Sometime tomorrow, swirling winds and UPS drivers will blow MISTY onto a front porch near you. Tuesday is release day, and I haven’t been this excited since my very first novel came out. A picture book is just a completely different animal. For me, it meant collaborating with an artist who has skills I’ll never possess. It meant being creative together. And it means coming up with a story that is as much visual as textual. Plus, this is a story for an audience I’ve never been able to reach before.

All-in-all, a completely different experience. One I’ve learned a lot from.

Before I get into how it came together, I should mention that there are a limited number of the signed hardbacks still available. These will be gone soon, so if you want one, now is the time. These are signed by me, and they are reasonably priced. Amazon has them discounted to $13.49 as of this writing.

With both the purchase of the hardback and the paperback, you can download the ebook for free. The paperback is only $6.99. Fancy coffees cost more than this. The ebook for your tablet or computer is just $3.99. I promise you, we priced these as cheaply as humanly possible. Why? We want as many people as possible to meet Misty. I think you’re going to really like her.

Beta readers of all ages have enjoyed their chance to read the story early. Jasinda Wilder says her youngest is infatuated with Misty and can’t stop reading the book. The first reader I put on my lap and read the story to spent the rest of the day carrying the book around and talking about Misty. It was everything I dreamed of when I considered doing this. It all started with a story I told to my nieces about a young cloud who couldn’t take on different shapes like her friends. And it grew from there.

Earlier this year, I spoke with my agent Kristin Nelson about really putting a children’s book together. Earlier, I had called out for artists on Facebook and had a lot of interested parties. But picking an artist and figuring out how to arrange it all felt daunting. Even Kristin wasn’t sure how to go about this. Neither of us had done a picture book before.

So Kristin reached out to someone with experience. This agent sent me links to artists she liked. My first choice was Nidhi Chanani, whose artwork is simply breathtaking. Seriously. These are prints you want hanging in your home. Luckily, Nidhi had been interested in doing a children’s book, and she had some free space on her calendar coming up. She also loved the text of the story and thought she could really bring it to life. So we began discussing how to work this out.

At this point, I assumed I’d be self-publishing an ebook and a print-on-demand paperback. So that part was handled. For paying Nidhi for her services, I looked to Audible’s ACX audiobook platform for guidance. I could split royalties with Nidhi or pay her a standard professional fee. I was really torn on which would be better for her. My natural pessimism when it comes to my books selling had me thinking I’d be taking advantage of Nidhi if she went for a royalty split. But the sliver of a chance that the story did really well would leave her out of any windfalls, however unlikely that might be. (Picture books are brutally hard to break into. Far more so than fiction and non-fiction).

We decided on a neat solution. I would pay Nidhi the going rate for a professional children’s book illustrator, and I would also cut her in on royalties if the book earned out and hit certain milestones. For those interested in doing a children’s book, know that the going rate for illustrations is quite high. I went into this assuming I’d never earn back a fraction of what I paid. I saw it as a learning opportunity, a chance to collaborate with an artist like Nidhi, and a chance to create something I’d be proud of for a long time.

The creation process was new to me. First, I sent the text to a children’s book editor, who helped me refine it a bit with some excellent input. Nidhi then did sketches based on the final text. After a round of feedback between myself, our editor, and both sets of agents, Nidhi completed the artwork. We sent off for proofs.

At this point, things got a little crazy. What started as a little project that probably wouldn’t amount to much got a little bigger. A publisher I never considered going with showed interest and offered to pay back the entire sum (a pretty big sum) that I’d put into the production (which included paying the editor). They also offered some other perks. At the same time, I was comfortable with and had already planned to go through CreateSpace and KDP. A common publishing decision these days, right? We decided to stick with our original plan, but the excitement about the book had us looking at the proof and seeing where we could make the book even better.

Which meant another round of revisions. Which is a lot more time-consuming, difficult, and costly than revising a novel. Here, we pulled in a children’s book designer, who took over the text layout, working from Nidhi’s layered files. Nidhi also came up with brand new spreads (her art in the book is just jaw-dropping). A new cover was made, and what started out great ended up absolutely beyond my wildest dreams. It was a massive team effort, a lot of work all around, and truly something I’ll always be proud of having played a small part in.

I go into this in detail, because several people have emailed me asking how I put the book together. What follows is my advice for anyone thinking of creating a children’s book with the hopes of breaking even or even turning a profit:

Understand that children’s books are still dominated by print sales.

Every bookstore owner I have spoken with about children’s books says that they are their best selling category by far.

The problem is that the bestsellers have been around for a long time, so it’s hard to make inroads.

The artwork has to be great, which puts many of us at a disadvantage. I think it would be easier for an artist to write their own story or hire a writer than it is the other way around.

A self-publishing partnership with a royalty split would be a great way for a new artist and new writer to try to break in. Just like with novels, I would plan on creating at least five works before gauging success.

The creation tools have gotten better. Amazon even has a tool that helps with the final file creation, complete with text pop-ups for reading on tablets.

Even more than novel writing, creating a children’s book should be thought of as a labor of love.

Finally, the quality I’ve seen from print-on-demand children’s books has been impressive. I ordered a few before starting this project, and getting 24-page full-color books for under $7 seems magical to me.

Even as self-publishing makes inroads, there are still unknowns and challenges ahead. Many people seem to think that certain books can’t work if they’re self-published. I disagree. I believe we’ll see literary works, seriously researched non-fiction, and children’s picture books all enjoy the same benefits that genre fiction is enjoying: The freedom to express ourselves, to reach readers directly, to price reasonably, and to pass along more earnings to the artists.

MISTY: THE PROUD CLOUD is one little experiment at seeing if this hunch of mine is true. If you want to help make that a reality, or see our finished product, order a copy today. Order some for Christmas presents! I think you’ll be impressed, and I think the doubters will be surprised.

The Book that Writes Itself

We need a German word for “thinking you had an original idea and then realizing many other people not only already had that idea but are well on their way toward implementation.” I hope someone can get on this. I bet someone already has.

A while back, I blogged about the possibility that one day my job will be taken over by machines. I think it’s important for all of us to consider this possibility, whatever it is that we do, and however outlandish the idea seems by current technology standards. How else will we see it coming? There’s a reason no one does. They all think their status is wholly unique until about three weeks after it isn’t.

Will machines ever write novels? That is, will novels ever write themselves? I believe if humans can stick around for another thousand years, it is inevitable. I’m also open to the chance (though skeptical) that some unforeseen advance in computing power or technology makes this possible in fifty years. Perhaps an actual quantum computer is constructed. Maybe in 50 years, a program like Watson gets more refined and has access to enough data and processing power that an emergent quality arises from what previously seemed wholly mechanical. That is, consciousness might flip on like a switch.

But how could this ever happen? How could computers ever learn to be creative? One of the answers to that question might be that creativity is more mechanical than we give it credit for being. This would be the Joseph Campbell school of thinking, where every protagonist is an archetype and every journey a hero’s journey. Or look at the work of Vladimir Propp, who detailed the 31 steps he thought every folk tale could be reduced down to.

Game theory and evolutionary psychology hint at the way that the human mind is both universal and largely predictable. Cultural relativists have no good answer for why we can read Sir Gawain and the Green Knight today and have it resonate with us across such vast time and in so many translated languages. The vast majority of fictional stories that work do so by satisfying our expectations. My romance friends will tell you that it isn’t a romance without an “HEA” or “Happily Ever After.”

This doesn’t diminish any genre by saying it’s predictable; it simply says something incredibly poignant about who we are. Imagine a murder mystery without clues or where the gumshoe never solves the case. Can you do it? Sure, but at some point the avant garde becomes a self-mastabatory exercise in trumping tradition just for the sake of obstinance. Mystery readers crack a book expecting the hero to nab the villain. The suspense is in how that happens. Just as the suspense in romance is how torn lovers will make their impossible union work.

In the formulaic there is the possibility of formula. In pondering how this might work, I drew on my expertise as a young writer who employed an advanced creativity enhancer known as Mad Libs. By supplying a few words into an existing framework, I created the unique with the help of some scaffolding. Perhaps the same could be done with fiction.

In some ways, we are already comfortable allowing computers to randomly assemble elements of our story. They’re called random name generators. It is often helpful to have a computer throw options in our faces rather than having to make up names ex nihilo, especially when we need a lot of names or a name that isn’t important but might bog down our writing flow. There are many out there.

What if rather than names, we had plot elements thrown at us by a random story generator? If this feels like a violation of our creative sensibilities, then what are story prompts? What do we call it when a random newspaper article inspires us to write a piece of fiction? I can imagine a tool that works something like this (with the thing in brackets coming from a massive bucket of like-type options).

[Protag] desires [Thing]

[Obstacle] is encountered.

[Protag] meets [Friend]

Duo meets [Enemy]

[Item] is discovered. [Obstacle] overcome. [Enemy] defeated.

Could this tool write a story from beginning to end? No way. Could it create a prompt to get someone started? Absolutely. Just like a random name generator can give us a boost.

Thinking this was an original idea, I then discovered that a group of coders have made considerable progress on just such a tool. Using Propp’s 31 criteria, they have assembled a random-plot generator known as the “Bard.” It is extremely crude, but the idea is to create plot prompts and ideas for low-intensity, high-volume situations. Like video games, where a group might need to come up with thousands of side quests. Just as we might not subject our protagonist to randomness, a video game studio might not yet use a tool like this for the main plot, but if these programs improve, then side quests would certainly qualify.

I put many hours into a video game back in the mid 90s known as Daggerfall that had randomly generated quests. You met random NPCs, who wanted a random item, which was guarded by randomly generated enemies in a randomly-generated dungeon (no two were ever the same). It was a much-touted advance at the time. It was buggy, but we loved it. A program was telling us stories. Many who played the game probably had no idea this was even taking place.

Sports lovers are in the same position today. They have probably read a synopsis of a game that was written by a computer program. The Big 10 Network has been using the technology since 2010. These programs are getting better, and computers are getting faster and faster, while their repository of data and examples grows exponentially. This is like neurons piling up. At some point, the level of complexity creates a new sort of output.

This is how computers obviated the need for legal discovery teams by learning to “read” millions of legal documents to prepare for trial. This is not a simple search function. These programs use something like an understanding of language to draw inferences and find precedents that teams of people would miss. And at a fraction of the cost and time.

Let me step back a moment and say here that humans will never stop writing stories and telling stories. It’s in our DNA. But that doesn’t mean the consumption of stories from other people is in our DNA. If we can’t tell the two apart, how do we stick to our principles as consumers? We won’t be able to.

In one of his dozen championship games with Deep Blue, Kasparov said he saw something that felt like true creativity in his opponent. He even intimated that the IBM team was cheating at one point by employing a grand master to take over the machine. He may have been one of the first people to gaze into the eyes of infant AI, feeling that sense of wonder at a small hand closing around his finger in response to being touched. Ken Jennings may have been the next to feel this. Make no mistake, what Watson did in mastering Jeopardy wasn’t just astounding, by some informed people it was considered beyond the realm of possibility right up until the day it happened. Also keep in mind that chess was once considered one of the highest expressions of our creativity. Everyone seems to forget this. Once the future arrived, we rewrote the past to make it seem inevitable.

Now imagine a tomorrow where people-written books and computer-written books sit on the same shelf. Both sets have authors’ names on them. All variably please some readers and not others. The prices are the same, so we can’t distinguish that way. But the computers can write billions of stories a year, and humans can only muster a million. What happens then? The odds are against us. And if you think we’ll be able to “badge” human stories, you might want to hear that master-level chess players have been caught employing computers during tournaments. Similar cheating will take place in this future. Like the sports fan, you’ll read what you think was human generated, but some of it will be from a computer. Who can guess which of my character names, if any, came from a machine?

There are many “first steps” in this process. In the world of coding, which has much in common with writing fiction if you subscribe to the Campbell and Propp view of storytelling, DARPA is working on a system that will automate programming from very few inputs. Automatic novel generation will happen when random plot generators are married to just this sort of text expander. “Fist fight” results in a gripping blow-by-blow action scene among the story’s characters. “Love scene” gives us a tender moment of appropriate length and reading age. Is it in the realm of science fiction today? Absolutely. But someone is already working on it.

November 13, 2014

The Reason for the Delays

I think we can now confirm that the reason for the delays for Hachette titles was that Amazon wasn’t stocking the books in their warehouses. It has been said over and over again that the delays during this dispute were due to Hachette’s inefficiencies, which I saw firsthand as a bookseller. Direct orders placed with a major publisher took 2-3 weeks to arrive. I can’t remember them ever arriving as fast as in a week.

I’ve seen two news outlets express confusion over why some of Hachette’s titles still show a delay of 2-3 weeks. Well, it’s because Amazon just created those orders yesterday when the deal was reached. It’ll now take 2-3 weeks to get those books to Amazon’s distribution center. Only then will the efficiencies of those distribution centers allow 1-2 day delivery. (Hachette might choose to “rush” these orders, which costs bookstores a pretty penny and probably involves unpleasant warehouse conditions.)

The way this has been portrayed in the anti-Amazon media and by Hachette authors made it sound like Amazon set Hachette books aside and said “Don’t ship those for another week!” and then rubbed their hands together and cackled. Which is ludicrous. The truth is far more banal and speaks more to publishers’ weak infrastructure and customer service, something they should work on if they don’t want to be beholden to retailers like Amazon.

Of course, how could they possibly compete in this area? Amazon has decided to take its profits and spend it on acquisitions and infrastructure, notably these distribution centers. They spend billions of dollars every year building these things. I think this pointless standoff showed publishers one thing: they rely on that infrastructure. Don’t forget that we used to go into bookstores, special order a book, and get a call in a couple of weeks. Or we’d put a book on hold at the library and wait weeks or even months.

Now we either get the book on our device in five seconds, or it shows up at our stoop in two days. Not only did the complaints of the last few months seem to forget the delays in the old way of doing things, they never once paused to appreciate the new world that tech companies have ushered in. They naively think that every company can simply do these things, that Hachette can also send books to customers in two days. They can’t. And Amazon is their biggest customer.

Amazon and Hachette Come to Terms

Finally. Hachette has put an end to their nightmare of a standoff and has agreed to terms with Amazon. This is great news for book buyers and Hachette authors and the industry in general. It comes right on the heels of Simon & Schuster signing a multi-year deal with Amazon for both print and ebooks, and the wording of that announcement was practically identical to the wording of the Hachette announcement today. What does that tell us?

It suggests to me that Amazon offered Hachette and Simon & Schuster the same deal. But what took Hachette most of 2014 to agree to took S&S a single offer / counteroffer. It must be said, though, that Hachette was at a serious disadvantage by being forced to negotiate first. The settlement with the Department of Justice forced the major publishers to negotiate with Amazon in 6-month windows. This was to prevent them from colluding with one another the way they did in 2009.

I don’t know how the order was picked, but Hachette drew the short straw. This meant two things: They had to negotiate with Amazon without knowing if their fellow publishers would fall in line and help pressure the retailer as they did in 2009, and it also meant that Hachette had six months less sales data to go on to judge the fairness of what Amazon was offering.

A year ago, jacking up ebook prices to protect print seemed like standard operating procedure. Over the course of this year, publishers have watched operating margins go up due to the rise in ebook sales, and many titles have moved a lot of units by employing sane pricing. In a way, Amazon was offering a deal based on what they saw coming, while Hachette was rejecting that deal based on what they saw in their rearview mirror. Simon & Schuster had six months extra of road to study. I hope this helps portray Hachette in a less harsh light. Again, they had a lot of disadvantages.

That doesn’t mean they weren’t wrong in this dispute, however. I believe they were. The wording of Amazon’s announcement today reinforces what I’ve assumed this offer was about since June, and that’s an incentivized form of agency pricing similar to what self-published authors receive. David Naggar, a VP at Amazon, said it thusly:

“We are pleased with this new agreement as it includes specific financial incentives for Hachette to deliver lower prices, which we believe will be a great win for readers and authors alike.”

This is exactly what many of us have been saying from the beginning. Now, this isn’t about who was right and who was wrong—this is about learning from history to understand the present and gauge the future. Twice now, Hachette and major publishers have waged wars with Amazon over the price of ebooks. They waged these wars with big box discounters like Barnes & Noble. Conflating our love of books with the virtuousness of those who package them is a very bad idea. Publishers belong to multi-national, multi-billion dollar corporations. They need to make profits. They do this by pushing prices up on readers and pushing wages down on writers. I don’t blame them for that (though I do try to pressure them to be more fair to both parties).

The people I blame are those who should do their homework, understand this business better, and get on the right side of these debates. The real damage has been done by those who refuse to fight for the little guys; the real damage has been done by the parties who seem to think that publishers can do no wrong and that Amazon can do no right.

This includes the New York Times and many other traditional media outlets. It includes The Authors Guild and Authors United. By waging a PR campaign without understanding the issues (often stating things that were patently untrue), these parties caused severe damage and helped to prolong this negotiation. They aligned themselves with a party that has broken the law to raise prices and refuses to pay authors a decent digital royalty. I don’t think this damage is done intentionally or with malice but by simple ignorance. As stated above, they conflate their love of books with a love of who puts stories in wrappers.

We need to do better in the future. Coverage of this industry should shift to coverage on what’s being done for readers and what’s being done for writers. These are the only two parties that matter. If publishers disappeared tomorrow, writers would continue to write great works of fiction and non-fiction. If Amazon disappeared tomorrow, readers would still seek these works out. The middlemen are not necessary. They are not crucial. They exist to serve readers and writers only.

So in the future, when middlemen squabble, perhaps we can be a little more balanced in our consternation. Perhaps we can start putting just a modicum of pressure on publishers to behave better, and maybe the vitriol spewed toward Amazon can be toned down a bit. Because in the case of Hachette / Amazon, the vast majority of the rhetoric got it all wrong. I’m usually an optimistic guy, but I have a feeling the people who were wrong won’t be able to see it, won’t be able to admit it, and will continue to fight on the incorrect side of history. But hey, maybe I’m wrong about this. I’d love to be able to admit it one day.

November 11, 2014

WOOL Comes to Life

Why wait for the WOOL film to get made when you can go live it?

Only costs $1.5 million dollars for a ticket. Comes with wallscreens (seriously), farms, and pumps to keep it all dry. Check out the WSJ article for more details.

I’m thinking every bedside table in this joint needs a free copy of WOOL.

Also: It’s obvious to me that Jules is the sheriff of this puppy. Check out where she moved Mechanical.

November 8, 2014

Who is David?

The negotiations between Amazon and the Big 5 publishers is often framed as a war between David and Goliath. What’s strange is that who gets to play David depends on who you’re talking to. Both sides claim him. The rare moments when people equivocate between the two parties, they state that this is really a case of Goliath vs. Goliath, which is far closer to the truth. We’re talking about multi-billion dollar corporations on either side.

But I’m still interested in how people who normally agree on a wide range of social issues find themselves on opposing sides when it comes to Amazon/Big 5. Of course, it’s not uncommon for people to agree on a lot of ideas and then hit a snag on some major topic. What is strange is when they use the same language to buttress diametrically opposing viewpoints. Both sides in this case say they’re trying to protect the little guy against the big bully. It’s like we’re on opposite sides of a valley, and we can barely see the two people duking it out down below on our army’s behalf, but our guy is definitely the underdog. Both sides think that ours is the champion of the little people.

And we both think we’re right. Where I might be a little crazy is that I believe the people I disagree with are sincere. I’ve had a number of exchanges with outspoken people from the anti-Amazon side, and I think these are good people who believe they are on the right side of history for taking their stance. I have some very close friends who vehemently disagree with me. So how do I square what I know of these people with how wrong I think they are?

It starts with questioning my own beliefs and positions, of course. I’m open to being the fault in this paradox. But as I look at the entire scope of this debate, and what is being said on either side, I think I’ve finally hit upon how both sides think they are championing David. It all has to do with how we frame our view of both Amazon and the major publishing houses. And I think we all get this incredibly wrong.

When I think of Amazon going up against the Big 5, I think of the publishing divisions of Amazon going up against the combined might of Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hachette, Simon & Schuster, and Macmillan. That is, I don’t think of Amazon Web Services playing any role in this fight. Nor do I think of Amazon Fire TV or the Amazon Fire Phone divisions as playing a role. I don’t even think of the distribution centers and the sale of physical goods, including media. I think of the people at Kindle Direct Publishing, Createspace, Audible/ACX, and Amazon’s publishing imprints. The book people.

I’ll get into why this is a mistake on my part in a minute. But first, let’s look at a mistake made by those on the other side. When these people think of Simon & Schuster, they don’t think of CBS, which owns the publisher. When they think of HarperCollins, they don’t think of Rupert Murdoch, Fox News, and NewsCorp. They just single out the book-publishing division that they love, and they compare that to the entire Amazon empire. They think of diapers, TVs, and how un-fun warehouse work sounds. They take everything that isn’t books out of their David’s army and forget all about that. And then they pit what’s left against the entirety of their foe.

Those of us who work with Amazon’s publishing divisions — either as self-published authors or as authors with their imprints — don’t think of the same “Amazon” when we’re talking books. What we’re thinking about are the men and women who work at Amazon who love literature. Many of them came from New York publishing. We think about what they’re up against compared to just the publishing component of NewsCorp or the American book wing of Lagardère Group, which owns Hachette.

In practically every way, Amazon is the clear underdog here. The upstart. The newcomer. They’ve published roughly 5,000 titles across their imprints to date, which is the number that the Big 5 might publish in a year. Meanwhile, the Big 5 have banded together to establish price floors with other retailers in what the DOJ found to be illegal collusion. And bookstores have refused to carry Amazon’s works, banning these titles from a large sector of the marketplace. For many of us, this is bullying far more severe than removing pre-order buttons.

When it comes to size, the publishing divisions at Amazon represent a tiny sliver of Amazon’s overall revenue. It’s quite possible that all of these divisions combined earn less than each of the Big 5 publishers do individually. The David from this point of view — not only in earnings but also in marketplace challenges that are either illegal or a result of book banning at retail — would seem obvious.

Compound this with the fact that Amazon pays authors more than publishers (anywhere from double at their imprints to nearly six times as much with their self-publishing platforms). Or the fact that they charge less to the consumer, where publishers have banded together to artificially raise prices, and the David is not only clear, but so is the side who is fighting for the little people. At least, from one perspective.

Publishers, meanwhile, are fighting for the health of large bookstore chains and for the top 1% of writers who benefit from massive distribution. They also benefit from a system that bars 99% of applicants from even entering. Again, this is the way those who support Amazon and other digital disruptors see these parties as David and the combined might of the Big 5 as Goliath.

But this view is just as wrong as the view that sees Amazon as Goliath and the publishing division of NewsCorp as David. Simon & Schuster proved this view to be false last month, when they agreed to a multi-year distribution deal with Amazon for both ebooks and print works. The major publishers have operated lockstep in some ways (from boilerplate contracts to digital royalties), but they aren’t the cartel we accuse them of. They enter subscription services variably. Some of them work out terms with their distributors while others don’t. Some have dabbled in print-only deals and have embraced genre publishing and lower ebook prices to a greater degree.

The truth is that there are a lot of Davids, all fighting for a place on the battlefield. Various alliances have cropped up over the years, but just as often, these Davids compete. In my view, the smallest David of them all is without a doubt Amazon’s publishing wings. To harp on the support they have from the larger company, again, is to make the same mistake of ignoring NewsCorp or Bertelsmann.

None of this is meant to settle any of the disputes, of course. It just helps explain (to me, anyway) how both sides can claim to be fighting on behalf of the little people. It all depends on how you frame and clump the people, and it’s usually done — by both sides — in order to buttress previously-held beliefs.

November 5, 2014

Publishers and the Smiling Curve

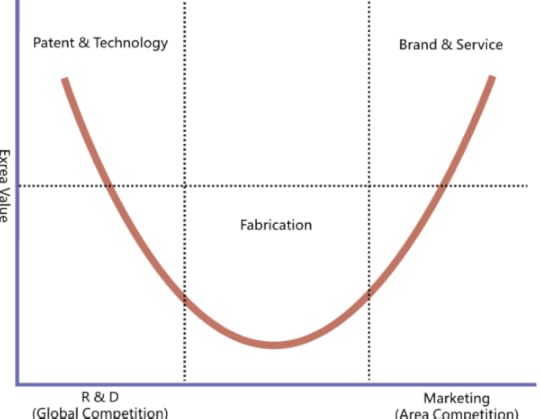

Profits are up at major publishing houses, so why aren’t more people in the biz smiling? Ben Thompson over at Stratechery.com points us to a curve that might explain those frowns. It’s called the smiling curve, and it represents the value added to a product by three phases —Development, Fabrication, and Marketing — that it goes through on its journey from concept to sale:

One way to understand this chart is to think of the height of the curved line not only as value but also as profits. Adding more value should allow leverage for commanding more revenue. So the company on the far left that develops the product and holds patents (or copyright) adds a lot of value and can extract that value in earnings. On the far right, you have the parties that can reach customers and drive sales, which also adds a ton of value and leads to large revenues. In the middle, you have fabrication.

Fabrication is crucial, of course, but the problem fabricators face is stiff competition. They are handed the product design and specs, and are simply tasked with assembly and packaging. While all three of the above phases are replaceable (customers can seek out a different product altogether, replacing the party on the left; or they can shop elsewhere, skirting the parties on the right), fabrication is by far the most fungible of the three. When a contract expires, a developer can shop around for a different assembler and negotiate better prices. The fabricator hasn’t invested in its own product designs, and they don’t control access to the buyer.

How does this apply to publishing? For the longest time, major publishers have held sway in both the left and right side of this smiling curve —where all the value is added and where all the profits reside. Their command of both sides was largely due to lack of access both to packaging and retail. They became necessary connectors between the people with the copyrightable material and the eventual sale of a finished good.

Think of the author as the person who works in the lab all day coming up with new patents and product designs. The scale needed to manufacture an actual product and reach a sales force was well outside her reach. She made up the R half of the R&D seen on the left side of the curve above. The development required the publisher’s editorial and art departments. It also required their contacts with printers in the middle of the curve and their access to retail chains, sales reps, and media outlets that comprise the right side of the smiling curve.

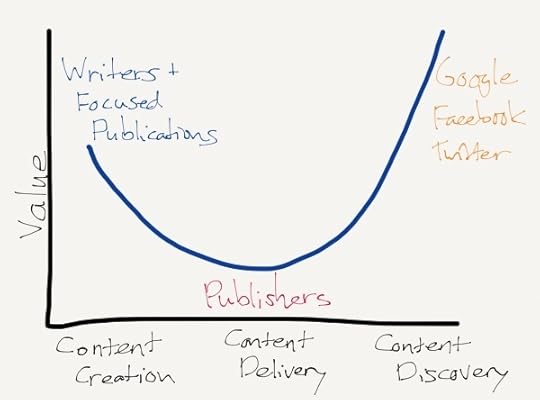

But all that has changed. Ben Thompson gives us this graph:

Ben is concentrating here on news and periodical publishers, hence the Google/Facebook/Twitter triumvirate on the right hand side. But it’s easy to see how Amazon/Apple/Kobo fit the same mold for books. With access to one-time development tools and services, writers now comprise both the R and the D on the left side of the curve. More importantly, the move away from print has minimized the role of large overseas printing presses, warehouses, and physical retail spaces. The center and right side of the curves have changed dramatically. Publishers have shifted down to the position of manufacturer or packager.

A common theme on my blog and in my thinking about publishing is that two parties matter most of all: The reader and the writer. Everyone else is optional, and their status depends on how much value they add to the relationship between the reader and the writer. We see this in Ben Thompson’s curve. The content creator is highly valued, as is the facilitator of discovery. Ben links to a New York Times article by David Carr on the power Facebook has among publishers right now. Driving readers to content is highly valued. Readers will remember who wrote the thing they loved and where they discovered it, which drives up the value for both parties. Readers will not remember or have much interest in who packaged it. This is a major problem for publishers.

To boil it down to its essence, what is it that readers love? They might say “books,” but press them further and they’ll talk about their favorite writers/stories or the places they shop/read. The content and the discovery. Practically no one will mention an imprint at a publishing house or a major publisher. These are the lowest value-add to the equation. They are the center and bottom of that smiling curve. That’s not to say that publishers don’t add any value — they certainly do — but what they add is miniscule compared to the manuscript and the store window. This is especially true as that store window becomes device screens and hyperlinks, which they do not control. They are also the most replaceable or fungible of the three parties.

In his brilliant piece on this dynamic, Ben points out the case of German news publishers who took Google to court to get paid for the news snippets that Google showed in its search results. The publishers wanted a bigger cut from the company (Google) that provided them the most access to their readers. Sound familiar? Well, Google’s response was simply to remove those snippets, which caused traffic to those German publishers to absolutely tank.

The result? Those publishers came crawling back. What the publishers glimpsed, perhaps, is that they now occupy the lowest center of the smiling curve. They no longer control the D half of the R&D. The snippet and the search results page have become the new package, not the delivered newspaper. The publishers also no longer control the marketing — proprietary search algorithms and the ubiquity of Google’s homepage now provide discoverability and access to the reader.

As Ben puts it:

The general takeaway is that Google proved it was adding value to the publishers, but I have a different angle: the publishers demonstrated that they provide no value to their writers.

He also says:

All of this is because of the Internet: by removing friction it removes the need for folks in the middle, and the result is that value will flow to the edges. In the case of publishing that is aggregators on one side, and focused, responsive, and differentiated writers and publications on the other.

Ben points out what many have seen as parallels in other entertainment sectors: HBO’s announcement to sell its shows direct to the consumer. Netflix bypassing the studios in the creation of material — and then the retail channels represented first by Blockbuster and then the postal service. And then there’s the number of self-produced entertainers who have used iTunes, YouTube, and Amazon to reach customers semi-directly.

Over the last two decades, networked computing has restructured where parties lie along the smiling curve. The pressure on those in the middle is coming from both ends, and it is coming from content creators and consumers. Word-of-mouth across social media is the new marketing machine, and no one but the customer has their hands on those levers. Meanwhile, the production of a finished, polished package is now in the hands of the person with the original idea. It is as if a sketch and a patent can come suddenly to life, while a technology company like Google, Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, or Apple can make that product available to whoever wants it.

Anyone not celebrating these events must not understand them, or they must not understand who exactly stands to benefit. Which will be the subject of my next blog post, as I look at how we confuse David for Goliath, and vice versa. For further reading, check out this other piece by Ben. Equally insightful.

November 3, 2014

Humans Need Not Apply

Computers will write novels one day.

Most of the people I mention this to tell me I’m crazy. It doesn’t matter that computers are already writing newspaper articles or stock analyses. It doesn’t matter that computers are already conversing with humans who are convinced that these are people on the other end of the line. Or that computers can beat us in chess (once thought to be more art than mechanics) or Jeopardy (once thought to be a puzzle no machine could ever crack).

Those who don’t believe fall prey to the fact that some past predictions have not panned out. The flying car is a popular distraction. This is as bad an error as the opposite mistake, which is to assume that every wild idea is an eventuality, given enough time. What makes more sense is to look at trends, see what is taking place in laboratories today, and make reasonable estimates.

This video (shared by a commenter on a previous post) does a fair job of this. You should watch the entire piece; it’s brilliant:

In a previous comment, I shared how I thought this might progress. It won’t be all-at-once, and it won’t happen in my lifetime, but it will happen.

First, computers will learn elements of storytelling just as they’ve already learned elements of language. Hundreds of novels will be extensively “marked up” by researchers. Parts of sentences will be tagged, but also elements of plot and structure. Programs will absorb all of these marked up novels and learn general principles. This is already being done with movie scripts, where machines can gauge audience reaction by looking at the placement of certain beats throughout the work.

The earliest examples of computer-written novels will be slight alterations of existing material. That is, a human author will write a “seed book,” and a computer will be able to modify elements of this to match readers. For instance, geography and place-names will match where the reader lives. All events in the same novel will take place in every reader’s home town, with street names and descriptions that match what people see in real life. The protagonist’s gender can be switched with the press of a button, with all pronouns tweaked to match. Or relationships can be same-sex to give more reading diversity for the pro LGBTQ community. Names can match the ethnicity of the reader or their preference.

This application is already within the scope of today’s technology. We might assume it hasn’t been implemented due to lack of demand, but I think the first publisher to try this will see that big data and the ability to customize the product will result in a higher level of satisfaction and engagement. Which will lead to more repeat customers and more sales.

The first place this will be seen is in the translation market. The advances happening here are amazing and destined to compound. Translators and foreign publishers will be creamed by this revolution, but readers all over the world and writers will benefit. Every book will be available in all languages, and computers will play a large role in “writing” these books. The same arguments about nuance and the meanings of words are precisely why no one thought a computer could win at Jeopardy. Keep in mind that the computer revolution is only a few decades old. We’re talking about what will happen 50 to 100 years from now.

In my lifetime, we’ll see grammar checking software put copyeditors out of work. With a few clicks, every novel will be error-free. Eventually, these programs will look beyond punctuation mistakes and typos; they’ll look for continuity errors and also historical inaccuracies. You’ll enter the dates covered by your historical fiction, and any mention of tech that doesn’t fit will be highlighted. Look at coding software and how it can debug as you code for examples of how much progress is being made.

Eventually, writing computers will advance until they’re able to pen individual scenes. There are already infant AIs that can converse with humans (a quasi-win went to an AI this year in the annual Turing Test), so dialog will get better. And then someone will program a computer to write an infinite array of bar fights. That one plug-in will join thousands of others. And then books will be written with the guidance of humans, who create the outlines of plot while computers fill in the details (a maturation of what James Patterson does with his ghost writers today). Eventually, even the ability to create plot will be automated.

If you doubt that computers can have a role in art, look at how digital painting has evolved. It starts with digitizing analog art, which is then filtered or modified to look different. Then photographs are manipulated to look like original art, which some artists are now doing for profit, passing off the entire affair as if hand-drawn. Music and fine arts are already computer-created and enjoyed. The same will be true for literature one day.

At first, people will balk. Then they’ll find out many of the books they’ve already read and enjoyed were written by a computer, and the author was an actor hired to sign books and talk about “motive” and “theme.” There will be a small market for “hand-written” books, just as there is an Etsy for those who prefer things made without the intervention of a machine. In ten years, we’ll see people chatting in the front seats of cars that are driving themselves. We will live with robots more and more (mine just vacuumed the house). And these things won’t seem quite so insane.

October 31, 2014

The Innovator’s Dilemma: Understanding Digital Disruption

Something Mike Shatzkin told me once has really stuck with me: “The people at the major publishing houses aren’t idiots.” In fact, I’m pretty sure Mike has told me this more than once, usually after I pointed out something that I think publishers should try and can’t figure out why they don’t. Mike could see that the assumption in my advice was that publishing executives didn’t know what they were doing.

It turns out Mike was right and I was wrong. Publishing executives aren’t idiots.

Neither were executives at practically every company that has been disintermediated or made obsolete by innovation. This is a common theme in business lore and among the general public, and it is dead wrong. Established companies don’t go under because they don’t understand their market, their customers, their product. Nor do they go under due to managerial blunders, lack of R&D, and all the other myriad reasons commonly proffered. In fact, companies lose market share and go under precisely because they are well-managed.

To understand how this works, you simply must read The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton M. Christensen. I’m not kidding. This book will blow your mind; you will never look at business transitions the same way ever again. If you have any interest in publishing (or how the world works in general), move this book to the top of your reading pile.

I can’t do the entire thesis justice, but I’ll entice you with a few of the lessons here. I’ll also say that this is one of the very few business books I’ve read that uses copious amounts of real-world examples. This isn’t guessing. This is hard-core theory in the best and most scientific use of that word. Christensen is even so bold as to make predictions in the form of case studies that are eerily prescient. I repeat: This book will blow your mind.

So how do companies go out of business if they are well-managed and if they can clearly see the disruptive technology heading their way? It helps to understand that most companies that are disrupted are the earliest to be aware of the disrupting technology and to even dabble in it or patent the new tech first. Like Kodak’s work with CCD sensors (which led to digital cameras). Or publishers experimenting with digital books decades ago. The problems these companies face are several, but the biggest are these:

1) The disruptive technology is usually lower-margin while in its infancy, and so a “win” is not big enough to motivate managers and employees.

2) Existing customers and sales networks are not interested in the disrupting technology. They want improvements and a continuation of current products. Greater profits are to be made satisfying these demands rather than appealing to new markets (and again, getting employee buy-in is difficult, so the pressure not to pivot comes from without and within).

3) The initial market for the disrupting technology is never precisely what the innovator thinks it will be.

A great example offered in the book is Honda’s entry into the market with the dirt bike. Honda’s attempt to sell a low-cost motorcycle to US customers was a failure from day one. Established dealers weren’t interested in the low-margin offering. Customers didn’t want smaller bikes for transportation. It wasn’t until Honda staff started using the SuperCub model off-road to let off steam that a different market was envisioned. The bike was retooled for off-road use and sold through sporting good stores. When Harley tried to emulate the product, their existing customers and sales forces balked. Once they gained entry, Honda began investing in “sustaining innovations,” which are refinements within the current market, and were able to take share from what existing players, like Harley, do best by moving up to road and touring models.

The computer industry is full of these examples, and Christensen uses the hard drive manufacturing industry for many examples. He also uses the mechanical excavator industry. By looking at which companies failed and which succeeded, he is able to test his theories, and you’ll be amazed at how well they hold up. If you are interested in the publishing industry at all, you’ll see evidence of his theories everywhere you look (same for music, TV, social media, etc.). I’m telling you: read the book.

In the end, you’ll see that Christensen offers some very actionable advice by looking at hundreds of real-world successes and failures. The key to creating a culture that rewards small wins and lower profit margins, while having the support of a larger company, is to spin off divisions that are allowed to operate independently while possessing the potential to disrupt the larger business as a whole. When companies set up the disruptive technology in-house, they almost always fail. When the disruptive technology is set up as a separate entity, they often succeed brilliantly.

I’ve always admired Apple’s ability to make its entire product lines obsolete. Why wait for someone else to do it? It requires uncommon vision to manage this from within, usually a very powerful and far-seeing individual or with a culture that inspires disruption. Steve Jobs was one of the former. Google’s culture of experimentation on company time is an example of the latter.

Consider for a moment that it was Amazon who practically made the ebook successful. Their business was in shipping things, initially books. Why would they dabble in ebooks and ereaders? I can easily see an IBM-like or Kodak-like moment where Google or Apple invent the ebook marketplace and Amazon becomes the hero to book-lovers and the last bastion of hope for the print industry (much as B&N went from villain to hero). Instead, Amazon disrupted its own primary business. They are trying to do so again with subscription models, fan fiction, crowdsourced writing platforms and discovery tools, and much else. These divisions are set up to be largely autonomous, where small wins are big deals for the divisions, even as AWS and other projects make outsized profits. The cycle of experimentation and a willingness to fail are an asset. Possibly the company’s greatest asset.

Another fascinating point in this MUST-READ book is that established companies often make their greatest profits right before they go under. How can this be? The maturation of sustaining innovations and efficiencies reach their peak just as disrupting innovations mature into the same marketplace. Think of the innovating technology as a line creeping upward but lagging behind the existing, sustaining technology:

That upward trajectory of both lines represents a mix of benefits, price, convenience, reliability, and so on. At first, the disrupting technology does not have a high enough mix of these features to appeal to existing customers. It’s left to early-adopters, who can stomach the higher price, lower quality, inconvenience, unreliability, etc. But at some point, the existing technology improves well past what customers demand. That is, the storage capacity is more than needed. Or the quality is much higher than what is required. At the point at which the disrupting technology, which was formerly only suitable for a smaller customer base with different needs, enters the mainstream marketplace, it’s already too late for established companies to pivot.

What gets in their way most of all? The existing cost of doing business. Bloat. The need for those higher profit margins. The disrupting companies are small and nimble, and they can thrive at 30% margins where the established company needed 50% margins. Overhead gets in the way, as does the existing culture within the company, which looks for wins of a certain size and has customer contacts and needs that have progressed to the top of what the market demands, while all the meat at the bottom of those demand tolerances are being gobbled up. Music purists will say that digital song files are inferior to analog, but customers said it was plenty good enough. Storage, convenience, immediacy, selection, and price trumped other factors like quality, physicality, curated local stores, etc.

In a blog post last year, I posited what I would do if I had to run a major publishing house. One of the suggestions I made, and one I’ve harped on over and over since, is the need for a major publisher to close shop in NYC and move to more affordable real estate. Reading Christensen’s book, I’m convinced that this is the only way one of the Big 5 can thrive in the publishing world ten or fifteen years hence. The hardest part of dealing with disruptive innovations is restructuring to subsist on different margins. Most companies make the mistake of trying to achieve this through layoffs, mergers, and a gradual reduction in size. Layoffs pare payroll. Mergers like that between Penguin and Random House increase efficiency by jettisoning redundancies between the merged entity. Reductions in size are had by closing imprints (or in the case of retail, like Borders and B&N, shuttering store locations). The first and last of these create a spiral toward irrelevancy or bankruptcy. Mergers simply delay the need for one of the other two options (mergers are really a combination of the other two options, as they often lead to an overall loss in positions).

So why is moving out of NYC the answer for one of the publishers? Cutting costs would allow for competition both with suppliers (authors and agents) and customers (readers). Without offices in midtown Manhattan and along the Thames in London, a rogue publisher would be able to pay higher royalties, thereby out-competing for the juiciest manuscripts, while also offering lower prices, thereby out-competing for market share. In fact, this is precisely what Amazon has been able to do. They pay their imprint authors 35% of gross, which is double what the New York publishers pay. Or they pay their self-published suppliers 70% of gross, which is nearly six times what New York publishers pay. At the same time, they offer their products for a lower price, taking crucial market share.

This is the pattern for the dozens of examples offered in Clayton Christensen’s marvelous book. You can see how it played out in other forms of entertainment, and how it is playing out right now in the publishing industry. You can also see in his work how difficult it is for companies to pivot to new marketplaces and customer bases without upsetting existing relationships, both outside the company and within. Getting editorial to move toward erotica or new adult and away from literary requires an entire cultural shift, which isn’t easy (or even advisable in many cases). Greater success can be had by spinning off a new division, setting them up elsewhere so that small wins feel like big victories, and let them gradually eat at your own market share. It’s the courage to create the iPhone, which will kill iPod sales. Or the iPad, which will hurt laptop sales. Powerful CEOs with singular vision can do this with great effort. Spin-offs and skunkworks can do it far easier and have done so successfully far more often.

Having finished the book a few days ago and considering the implications for Christensen’s theories, I’m willing to make some predictions. Predicting the future, of course, is idiocy. It’s not possible. But the power of theory comes from its ability to offer prediction and reproducibility, not its strength in describing what has already happened. So my predictions are these, with the idea of revisiting this on my deathbed to see if I learned anything:

1) Low-cost reading entertainment will trump high-cost, even if the former comes in a less-adored package and with lower fidelity. That is, even if most readers “prefer” paper books and even if the low-cost items contain more mistakes or typos.

2) Print manufacturing and sales distribution will be destroyed by digital. This might seem obvious to some, but many industry experts are claiming that ebook growth has leveled off. I think ebooks will become 95% of fiction sales and 75% of non-fiction within fifteen years.

3) The first company to go all-in with mass market paperbacks will control most of future print market share. Grabbing 90% of what will eventually be print’s roughly 20% of the market might not sound like much, which is why no one is going after it now. But the low-margin option that customers want but that established industry leaders see no profit in is the basic definition of a disruptive technology. The first print-on-demand machine that can handle the thin paper and trim sizes needed for mass market POD will make a lot of money.

4) Physical bookstores will become much smaller and more specialized, or will simply move inside other retail spaces.

5) Most damning for my profession: Reading options will decouple from what we think of as “books,” as most reading will be done communally or on streaming websites or serially. I give this one another fifteen years before it’s obvious. Say 2030. What we think of as a “book” will be the vast minority of what’s read. Works will become shorter in individual package but longer in overall scope. Think seasons of TV.

6) Because of (5), authors will make far less per “read” in the future, as there will always be more people creating than buying (and this will only become more true as time goes on). The same forces that are allowing self-publishing to disrupt major publishers will eventually allow hobbyist writers to take vast market share from self-published authors. Tools that automate copyediting will improve until this is done for free and with the click of a button rather than hiring out editors. IBM’s Watson technology makes this practically feasible today. Also, the packaging will become automated, both with perfect digital file formatting and auto-generated cover art. Again, both will be free and as easy as clicking a button. This will greatly expand the pool of potential authors, forcing out many who are disruptive forces today simply because they are able to tackle these obstacles themselves or are willing to hire others to do so.

7) In fifty to one hundred years, authors themselves will be obsolete. No one will believe this today, but it’ll probably happen sooner than I’m giving it credit for. Already, computers are writing columns for the sports pages, and readers don’t know that’s what they are reading. At some point in the future, books will be written in a few seconds, tailored to each reader based on what they enjoyed in the past and what people with similar tastes enjoyed. E-readers will measure biometrics during the reading process to refine future works. Books will be infinitely diverse, but there will be a cultural clash over whether or not the empathy-building advantage of fiction is lost in a world of such catered entertainment. Human writers will be esoteric and admired by those who consider themselves to have the highest tastes. But it won’t change consumption habits; readers will gobble up stories written just for them. And if the pulse fails to race, a beloved character just might meet their end. We human authors won’t have to guess who to kill and when. It’ll happen when you very least expect it.

Don’t let the wackiness of these last predictions dissuade you from diving into The Innovator’s Dilemma. It’s a fantastic work. I’ve never put this much time into a blog post about a book recommendation. I’m telling you, this is a work that will explain so much of what’s going on around us. You’ll love it.

NaNoWriMo 2014

It’s that time of the year to disappear for a bit. November is National Novel Writing Month, an annual festival of carpal tunnel and obsessing over word counts. The challenge is to write a 50,000 word rough draft in a single month. It requires writing 1,667 words per day for thirty days. It’s not that the daily load is too heavy — it’s that once you set it down, it’s hard to pick it up again.

Missing one day means working hard to make up for it elsewhere. Falling behind leads to more falling behind. Distractions like social media interfere terribly with getting work done. You have to sacrifice short term and shallow gains in order to achieve something bigger and more lasting. In all of these ways NaNoWriMo is as much about learning our limits and how to forgo immediate self-gratification than it is just about writing.

And you don’t have to sacrifice quality for quantity. Many writers produce their best work while writing under pressure or for a deadline. This is the only way some writers get work done. For me, the compressed nature of the writing means I can’t leave the world I’m creating. When I’m away from my keyboard, I’m daydreaming about the story. It’s all I think about for a month. And so the plots can be more involved, the characters more alive, the world more real.

I invite all of you who write or dream about writing to join. It’s a global event, and it can change your life. Even if you just want to write about your past, your thoughts, or create a collection of poetry. Whatever small entertainments you have to set aside for the month, I promise you they’ll be there and waiting when you get back. Meanwhile, you’ll have created something that will last a lifetime. Something that will need a lot of editing come December.