Hugh Howey's Blog, page 13

September 6, 2016

A Peek Behind the Curtain

Major publishers are in trouble. Publishers Weekly reports declines across the board at all five major publishers. What is happening here is not new, as much as publishers would like you (and themselves) to believe. For the past four to five years, publishers have found growth almost exclusively through acquisitions, mergers, layoffs, and the largesse of their primary retail account, Amazon. All of those forces have run out of room.

As self-published books took off and began commanding a growing share of the book trade every quarter, publishers were able to weather the storm mostly because of increased profitability as more of their business moved to Amazon. Even as they damned the online bookseller, they profited from lower returns rates on physical books thanks to Amazon’s predictive on-time ordering. (The returns rates at bookstores could be around 40%. Amazon shaved those to under 5%) Publishers also made bank on ebooks as Amazon paid publishers their full amount while discounting to the bone and taking the hit on the retail side. When publishers fought for a return to agency pricing, they fought for an end to this discounting, which has pushed more and more sales to self-published authors. Those sales (those readers) are probably never going back.

Let’s dispel a couple myths: The first is the idea that book sales are languishing because there hasn’t been a breakout hit like (whatever book sold well the previous year). I’ve been seeing this line trotted out for two decades, whenever a publisher has a lull. Usually it’s a single publisher explaining their performance in a quarter due to “Not having a hit like we had in Insert-Book-Title-Here last quarter.” These days, it’s the running excuse for the entire book trade. And it’s absurd. Think about the number of damning things publishers are saying about themselves when they make this quarterly excuse:

• They are admitting that they can’t create a bestseller

• That none of their marketing and promotional tools work!

• That book sales are either all luck, or…

• Completely dependent on the talents of the authors that they have historically abused.

Beyond the weirdly circular reasoning of, “The reason we didn’t make as much money this quarter is because we didn’t have a book sell a ton of copies this quarter,” there’s a lot to be wary of in the above bullets. As a writer (the peeps I care most about), it should be eye-opening. None of the promises a publisher makes to you can be kept. It’s out of their hands.

Whatever they tell you they’ll do to make your manuscript a bestseller, they said to thousands of authors in the past year, and they failed at all attempts. Meanwhile, I know of a dozen self-published authors who have broken out over this time. I had a married couple on the boat for lunch this week who are both deciding when they should quit their day jobs, as they are steadily making 5 figures each month. If you go to writing conferences, you’ll run into dozens of silent success stories like this.

Probably the most damning evidence that publishers can no longer drive sales is the sad excuse for books that have kept them afloat. Last year, it was a rejected rough draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, published against the wishes of the dying author. This year, it’s a play not even wholly written by JK Rowling. And over the last two years, it has been coloring books hiding the slide in physical book sales. None of these things are books. Publishers are no longer in the book trade; they are in the what-the-hell-can-we-do-to-make-a-buck trade.

The irony here is that for years we’ve heard that major publishers are all about Literature, with a capital L. And Amazon is about diapers, and Google is about data (scanning all books), and Apple is about devices (selling iPads). The reality is that all of these companies are about profits, so their actions should be compared, not their motivations, which are largely the same. Their actions tell us about their philosophies as they pursue those profits.

Major publishers have colluded in order to screw the reader, have offered ever worsening book contracts to screw the writer, and have resisted innovation in an attempt to harm their top retail account. Higher prices, fewer rights to authors, and fewer sales channels have been where they’ve exerted their muscle. Let that sink in.

The actions from the west coast have been quite different. The new publishing leaders (Amazon, Google, Apple), have opened their markets to more voices, have paid higher wages to writers, have passed along greater savings to readers, and have increased choice and availability in formats.

There has been some good news from the smaller publishers, as indie publishing houses figure out how to compete. Some medium sized publishers now offer the print-only deals that the Big 5 are loathe to offer (I’ve signed four more of these deals in the past year, and I know of other authors who have seen them as well). My agent and I have also seen hard terms of copyright with some of these deals, limiting the terms of copyright to five or seven years. And some of these publishers have dabbled with promotional opportunities at Amazon that major publishers have avoided for fear of making more profits alongside their biggest retail account (bizarre).

What can we expect to see next? Well, what if we started from scratch, today? What kind of book trade would we build? It wouldn’t be the large big-box discounters like B&N (which just changed CEOs again, and is probably 2 to 3 years from going under). If I was building the book trade of today, I’d mostly do what I described in this blog post if I was a publisher, and this blog post if I was a bookstore owner. What we really need back today is Waldenbooks, with a small footprint store in every mall and in a lot of strip malls. Like a Gamestop or GNC type of franchise, one that people can buy into and have the freedom to run like a community indie store. Those are the kinds of stores Amazon is building (they just announced another in Chicago). It’s the opposite of what B&N is thinking of doing (selling wine and opening cafes).

The Big 5 are going to become the Big 3 or the Big 0 eventually. Medium sized presses that are doing the right things will eventually overtake them. The first major publisher to go all-in with Kindle Unlimited will make bank and survive (and seriously impact indie sales overnight). Amazon is going to continue to dominate in print, ebook, and audio, because they think about the reader first. Indie stores are going to do well because the world is urbanizing, and people will support local shops and continue to buy books that they never actually read. And writers are going to have new opportunities in gaming and VR spaces, as well as the genres that publishers neglect, until the day that AIs are writing all our books for us.

Until then, you can expect publishers to make pretty much every mistake they’re capable of making. Ingrained biases and wishful thinking will continue to lead the way. A recent survey that showed more people prefer print books over ebooks will be taken as gospel, when Amazon knows from their data that ebook readers read an order of magnitude MORE books than print book shoppers. So while publishers mold their business decisions around the people who read two books a year, Amazon will continue to cater to the readers who would consider this a slow weekend. It doesn’t take a genius to sort out who is going to win market share when that sort of lunacy is taking place.

Five years ago, I called for publishers to do whatever it takes to gather data on their readers’ habits, even if that meant giving away ebooks or partnering with Amazon on every promotional opportunity they could (in exchange for some also-boughts data). Instead, they have pushed up the price on the one format they could easily track and use to entice readers to get onto mailing lists. They have fought with Amazon over the discounting that was only hurting Amazon’s profits. And they have resisted subscription services that have seen actual growth (Kindle Unlimited) while dabbling in services that were operating like Ponzi schemes.

These are the same publishers who damned B&N as the devil until it was too late, and then saw B&N as their savior. In a few years, while profits are still plummeting, and publishers are blaming it on the lack of a bestseller like Book X from the year before (probably a rejected rough draft of a play about a paint-by-number artist), they’ll turn to Amazon to save them and have to wrestle with a beast that they created. And all of it was unnecessary.

All they needed to do was treat their authors better, do more for their readers, and pare down their costs. The Amazon formula for success. Instead, they’ve done the opposite on all three accounts. And they wonder why times are tough.

The post A Peek Behind the Curtain appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

September 1, 2016

This is Only the Beginning

I want you to do me a favor and watch these two trailers for the same film:

I know which one I like better. The first trailer captures the mood, while the second tries to give us the plot. As someone who now avoids movie trailers, because I’d rather watch the 120 minute version of the film rather than the 3 minute version, the first trailer is exactly what I’ve been begging Hollywood to give me for well over a decade.

Only, Hollywood didn’t give me the first trailer. IBM’s artificial intelligence Watson did.

You can read about the process here. And yes, a person was involved in creating the final cut, but it’s easy to imagine this final step being automated in the near future.

Earlier this week, I met up with the legendary science fiction author and translator Ken Liu (you should totally read THE GRACE OF KINGS). Ken and I discussed the inevitable future in which machines and humans will one day write together, and the future beyond that when humans won’t be needed at all. I’ve blogged about this several times in the past, and Ken has written about the same topic in his coverage of NaNoGenMo, an annual attempt to create an entire novel using machine-learning bots. It will happen, the question is when, and what will the transition to there look like?

In another conversation this week, I was asked how long it would be before a machine wrote a novel that was better than the human counterpart. I believe we’re a long way off, but it’s striking to me that of the two trailers above, it’s the Watson-generated one that makes me want to see this film, and the human-created one that makes me feel like I’ve already seen the film. This is a unique circumstance of course, because the ephemeral and surreal leave me wanting more, while the chronological and story-driven teaser leaves me only mildly interested. Ephemeral and surreal might be what current AIs do best, as evident in this film, written entirely by an AI.

There are parallels here with children. I’m often shocked and moved by the things young kids say. Without a filter, and with a limited vocabulary, they often cut right to the heart of an issue with startling precision, or they dance around the unknown with stirring poetry. They see things differently, and they communicate differently, and many conversations are enlivened and enriched by their participation.

This is already true of artificial intelligences and machine learning artists.

We may mock them at first, the way we laugh when a baby babbles, but soon they are dropping insights, then painting striking imagery, then crafting wholly new stories, and then winning awards hidden behind the guise of a human author. I wrote about this last possibility in THE PLAGIARIST, where a man steals art from computer-generated worlds and passes it off as his own. I believe this will happen one day, and we will have to figure out how to cope with it. Who owns the art? The discoverer? The machine? The original programmer? What about when these bots are open-sourced, crowd-sourced, or self-replicating?

There are four primary stages or phases that I can see us going through before a wafer of silicon is awarded a Pulitzer. They are: Random Generator, Filter, Centaur, and Turing

We’re already in the first stage, Random Generator, because machines are helping us write novels now. Not everyone takes advantage of these tools, but I know of many authors who will fire up a random name generator when they’ve run out of ideas for secondary characters. The computer makes a number of suggestions, and the writer picks the one they like best.

This stage is going to increase in complexity, with plot points and locations offered up at random, as well as dialog choices. It’ll be a Mad-Lib style grab-bag, and the machines will learn from the users what choices win out (the way Google learns which search results are most helpful). In this way, they will only get better. We use writing prompts from professors and craft books already; the computers will be even better at this.

The second stage, Filter, will have a lot in common with an area in which we’re already creating art with the help of machines, a stage that Ken pointed out to me. Most of us have taken a photograph, swiped through a series of filters, and chosen the resulting pic that we like best. The Prisma App takes this to another level, creating works of art in various styles based on the photographs we feed it. We’ve been doing this both in photography and music via filters and effects for a while now. Soon, we will do it with the written word.

Imagine, for instance, taking a novel written in the first person, pressing a button, and reading through the same draft in third person. Or imagine a manuscript written in present tense, and quickly moving it all into past tense. This is in the realm of possibility today, if an engineer were so inclined. With a quick swipe, the flavor of the text is changed, and it’s up to the writer (or reader) to decide which style they like best prior to publication. Or better yet, just as readers can today change the size of the font in their Kindles, imagine being able to choose to read The Hunger Games in third person past tense, if you prefer this style.

There will be an uproar, of course, among some creatives who think the manner in which a work is presented should only be up to them, but that cat got out of the bag years ago, wrote some slash-fic, made a version of its favorite novel without any of the cuss words in it, read the last chapter first to make sure everyone important survives, and left a dead canary on the stoop. Artists are going to have to become comfortable with readers owning the right to read in whatever style they like. Person and tense will be suggestions by the author, not holy writ.

Imagine further being able to change the genders of characters, or their race, or sexual orientation. Now we cross into very interesting waters, because some of these choices are underrepresented due to commercial choices made by publishers. Will we lose some of the power of fiction if readers are able to choose to read only from the point of view of characters like them? What will this new power do for the empathy engendered by fiction? If used properly, it will be a boon. If used improperly, it will be a setback. Me? I’m for having more choices and options and seeing what the reader decides.

All of this will be moot as we get into the third and fourth phases of AI literature. The third phase will entail novels written by Centaurs, or the partnership between human and machine. Competitive chess is already in the Centaur stage, with these mixed teams beating any of the top players or computers when they don’t partner. One day, I will sit down with my writing program, give the barest of prompts, and the computer will spit out rough prose for me to revise. Or I will write, ask for a prompt, and get a suggestion in return. We will co-author the work. Neither of us could have written the final piece alone. This is some wildness to consider, but I reckon it’ll happen during my lifetime (I’d say we’re 15 – 30 years away).

Fourth stage is the Turing stage, the holy grail for readers, the end of writing as a profession, and I give it anywhere from 50 – 200 years. Entire novels will be written from scratch by machines, a million novels spurting out in the blink of an eye, and they will be tailored to individual readers, win major awards, and be as sublime and moving as anything we’ve ever read before. We balk at the idea now, but just as manually driving a car will seem insane one day (unless on a closed track by daredevils with death wishes), a handwritten novel will also seem bizarre. Why do with long division what a calculator on our phone can do for us?

Sure, people will still write, but very few will read these works. And the process will happen so gradually that hardly anyone will understand what has happened. We already read sports stories and financial articles written entirely by computers, and we either don’t notice or don’t care even when we’re told. Soon, these will be news articles, and pop culture articles. Things driven by fact. Then we will read reviews of books and film written by machines like Watson, who can analyze a work and tell us if it’ll be a bestseller (this is already a thing). From giving a simple grade between F and A, the machines will gain a language and an opinion to describe why a work is good or bad. We will get used to these developments in stages. The end result is inevitable. As a reader, I can’t wait.

The post This is Only the Beginning appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

August 11, 2016

The Scaffolding

I’ll never forget where I was sitting, and what I was thinking, when I first felt pity — rather than anger — for a bigot.

This was back at the College of Charleston. I was head over heels for a girl named Kim at the time, and we would hang out at her place or in the little bar where she worked. Perhaps it was the heady excitement of being in love that put me in a forgiving mood, or maybe it was something I’d picked up in a class, or just me finally getting around to understanding what most people know already.

A few guys walked into the bar, and one of them used a racial slur, and it was so nonchalant, so brazen, without an ounce of remorse or even self-awareness, and instead of seeing this guy, for some reason I saw his upbringing. I saw his peers, his parents, the South, the hard divide of Calhoun Street, Confederate flags, this entire support structure beneath him.

It was weird, the complete lack of judgement I felt. It wasn’t the same as forgiving someone, but it was close. My thought was: how do you blame a fish for not knowing how to fly?

Have you ever seen someone parked like this:

When I saw cars parked like this, I used to assume the driver was oblivious, perhaps even unempathic for their fellow drivers. How could someone be so unaware of their impact, however minor, on the world around them?

And then, one day, I had to park beside a car like the one above, because the other half of the neighboring spot was also encroached, and there were no other spots left. So I parked straddling a line, just like the other two cars. Walking away from the space, I turned and saw our cars like that, and it hit me: What if the other two drivers come out and leave? My car will be left looking just like the one above. The revelation that followed was this:

It probably wasn’t the other drivers’ faults either.

One car parks a little too close to the line, which cascades throughout the day, until people are parking in what looks like a rude manner. But it’s not anyone’s fault, really.

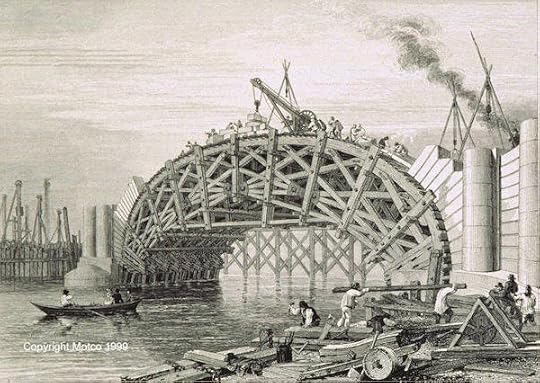

It’s not just ugly behaviors that are built up in this way. Some of our most beautiful creations employ support structures that are no longer around to admire and to demystify the building process. I’ve always loved arches and bridges, ever since I was a little kid. I remember learning about the keystones at the tops of arches that hold them all together, and they seemed magical to me. Heavier than air, and pushing down, but somehow holding everything up!

What hurt my head was trying to figure out how those stones were put into place to begin with. Before the keystone is there, what’s doing the keystone’s job? Why doesn’t the arch fall down as the builders are trying to erect it? Because the rest of the arch is holding the keystone in place, just as surely as the keystone is propping up the rest. The whole is needed. As a kid, I imagined a bunch of workers all holding stones above their heads at the same time. Because I didn’t know anything about scaffolding.

When you see how things are built from simpler support structures, so much of the magic of what — at first — seemed impossible disappears. But the loss is fleeting, because it’s replaced with the magic of human ingenuity. Or the magic of seeing root causes and how things come to be.

There are different types of scaffolding everywhere. Once you start looking for them, you can’t stop seeing them. Any temporary support structure qualifies. Some of these structures are just ideas, or theories. Some are environmental influences. Once they’re gone, or not seen, we can be left with confusion or wonder when the story is so much simpler.

The Egyptian pyramids befuddled those who don’t see scaffolding. Scientific progress can do the same. And so can technology.

The same semester that I was learning to see scaffolding — and to understand bigotry and poor parking — I was in an anthropology class. We had to write a paper on the Clovis point tradition, which was a dominant style of flintknapping that spread through the Americas (I think. It’s been a while). Being the smartass that I am, I wrote a paper instead on how poorly we understand human history when we focus only on the things that remain. Archaeology becomes a study of the hardy, the things that last. We don’t appreciate how minor a role those things play. The millions of iterations of wood, clay, leaf, and twine tools are lost to us.

Take the time to watch this entire video (it’s the best part of this stupid blog post):

A few hundred years later, what will be left of this primitive forge will be some metal ingots and that single stone tool used to split the wood. A college student will write about a people who threw spears at animals. The rest of the tools are gone.

Without seeing the scaffolding, we can’t understand primitive man any more than we can understand bigotry. This guy playing with the elements around him, and using just his noggin, his tinkering, and what he knows (or thinks) to be possible, is discovering more about ancient man than a thousand people digging in the dirt and pulling up rocks.

Perhaps the most amazing thing about the video is that it dispels the notion that our current technology would take generations and generations to reproduce if we started from scratch with only our collective wisdom. Here is a case where we understand that scaffolding exists (you have to make wood tools, to make stone tools, to make metal tools, to make better and better metal tools), but we overestimate the complexity of the scaffolding. Or we underestimate human ingenuity. I’d wager that two dozen of the right men and women could build a simple electrical computer out of nothing within a year. And I’m being conservative. If they pulled it off in three months, I wouldn’t be shocked. Yeah, that means making batteries, dynamos, wire, and glass.

Primitive man had almost nothing but time and cleverness, and these are a potent mix. What arises at the end might seem miraculous, but only because we miss all the support structures along the way. The storehouse of knowledge is by far the most important technological tool, and in the time before writing this was the most ephemeral scaffolding of them all.

Where we most need an awareness of scaffolding is in controversial topics, the ones where emotions run hot. Like the poorly parked car, it’s easier to judge what we see than it is to look for what’s missing. When that college student walked into the bar, using language that normally drove me to anger, all the fungible elements that built him up are gone. Seeing those, in the casualness of his peers, allowed me to approach him from a place of understanding. Empathy is held by flying buttresses such as these. We need them to hold up the often thin and brittle walls that make up our compassion for those we disagree with.

Religion is an example. As I moved away from religion and toward science, I became bitter and judgemental of the former. How can people believe some of this dogma, especially if it’s built on hate? And how can religious thought ever hope to understand the natural world, when science does it so much better?

But for a long time, religious ideas were the most sensible with the data at hand. And for a primitive people whose populations were tenuous, rules to force procreation made a lot of sense (don’t masturbate, don’t be gay, don’t use contraceptives). Where the scaffolding pushes some of these systems can seem insane many iterations later, but a more studied look usually shows a natural process. This search for origins is done without judgement one way or the other on the outcome; that is separate. But in what better way do you think we can bridge understanding with those who are straddling parking lines, perhaps feeling foolish but also justified in their position, knowing quite well how they got there, or perhaps not knowing that any other option exists?

It’s always better to discover the root causes of things. We might learn that many of our biases are wrong (the driver of the car above might not deserve our shaming). We might also be able to reach out to someone in a compassionate manner. When you remove the blaming aspects of judgement, you provide an opening for people to change. Blame causes entrenchment. Most people know that they are good, and so they employ cognitive dissonance to justify their handful of poor features. But when those things are not their fault, it’s far easier to get rid of them. We often just need an opening, a way to bow out gracefully.

Often we are begging for a way to alter our circumstances, to apologize, to change our minds on a divisive topic. But the space is not being made for us to move to the position we long to take, or to heal wounds with someone we love. It sucks to say that the onus can be on the people who are hurt, rather than the people doing the hurting, or that the onus can be on the person with the more sound position, rather than the person whose mores need updating, but this is often the case.

Scaffolding needs to be erected to help prop up the person who is at fault. And while the person who is under the shaky arch feels like they’re the one who needs saving, often their feet are on solid ground enough to help erect that scaffolding.

I can think of times that I was angry at someone I loved for an unjustified reason, and even when I realized that I was in the wrong, I felt like I needed to hold on to that anger to make sense of my initial reaction. All the emotinal responses and triggers, all the words exchanged and the little annoyances of the day, were gone. I was left in a strange place, like that car straddling the line, and I had to make sense of this plus the feeling that I’m a good person. All it might take is a loved one pointing out that it’s been a long day, or that they know work has been tough, or that they know someone just needs their morning coffee, and suddenly you have a way down. A reason besides the fact that you were being a shit for a little bit. Just enough to be able to admit you were being a shit, apologize, save face, and move on.

For understanding people, ourselves, history, and technology, nothing is as powerful as a grasp of the temporary support structures that make things possible before disappearing from view. I see the shadows of them everywhere. I feel how they created the good and bad in me and others. It’s hard, of course, to see things that aren’t there. But it’s so rewarding, comforting, and illuminating when we try.

Oh, before you go, check this insanity out:

The post The Scaffolding appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

August 2, 2016

Like Unto Children

Terminator, The Matrix, Ex Machina, Robocop, I, Robot, 2001, A Space Odyssey. They all follow the formula of: Man makes machine, machine destroys man. It’s a sci-fi trope. But what if we’re wrong about how we will feel about our creations? I have a feeling it might go much differently. I think mankind will one day go extinct, but that we won’t mind.

Heresy, right? Millions of years of evolution have created an intense drive for self-preservation. The idea that we might willingly be replaced — even replace ourselves — is unthinkable. Except that we do it on a smaller scale every generation. We have children, invest in their upbringing, marvel at all they do and accomplish, all the ways that they are more incredible than we were, and then we move off and leave room for them.

Only because of our infernal mortality, you might say. Well, I don’t think immortality is something we’ve thought through very well. Medical science might provide individual immortality one day, but it will only be immortality against disease and age. Accidents can and will still happen. In this scenario, I see the immortal living lives of pure abject terror, afraid of venturing out. We wager according to what we can afford to lose. I take chances with my remaining 40 years on Earth that I might not take if I had 4,000 or 40,000 years to live. I haven’t seen this conundrum raised before, but the effects will be very real. As our lives are extended, we will hold them more dear, and so live them less fully.

There’s more to consider: Is there truly a difference between making room for progeny and living 400,000 or 4,000,000 years? What about four BILLION years? We can’t call it immortality without thinking about truly large numbers. Imagine a life lived over 4,000 years. Are you really the same person? Every cell in your body will have turned over several times, and memories of anything that happened thousands of years ago will be crowded out by the more recent. Now imagine 40,000 years of this life. 400,000. At some point, the reflex to NOT DIE runs up against the reality of very large numbers. Every day might be a sane decision to carry on, but the idea that this is a unified life is challenged by the ability to remember such a life, or be a consistent actor through it.

It may require us attempting these things to learn the truth of them. Or more likely: We may understand the philosophical insanity of immortality long before we acquire the means. Living healthy lives for a century or two seems doable. Being around for billions or trillions of years is either a hellish torture, or just a series of loosely disjointed lives that only have in common a name and a distant past. Which is what generations of people already accomplish.

I think what will change our calculations is the advent of machines who earn our full empathy. I think they will be like unto children for us. In science fiction, we explore with robots something that happens naturally, and that’s the terrifying and awe-inspiring moment when the next generation becomes more powerful than we ever were. They throw a spear further and with more power than we could. They run and jump higher. They raise their kids more beautifully than we did. They do things with fire, and arrowheads, and pottery, and tapestries that we couldn’t imagine.

I’ve watched parents watch their kids with a mix of confusion, awe, and horror. It’s the way a three-year-old navigates a phone more adroitly than her parent. Or how easily a toddler interfaces with a tablet. It was how my father gave birth to someone who could program his VCR just by fiddling with it. Brute force gives way to intuition, gives way to fluency.

The only missing piece in moving the chain of creation to robotics is the empathy, and I think that will come easier than we realize. We already empathize with the crudest of our creations. I remember being concerned for the safety of KITT in Knight Rider. It was often KITT who was in trouble, and Michael had to save his ride, his partner, his best friend. These were worse moments for many viewers than when it was Michael who was in trouble. Because the car was our creation. We were responsible for it, the way we feel responsible for a child or a pet. This makes their fate more dear than our own. It makes it possible to step aside and make way.

It’s easier to step aside when we see how the world will be better under the next generation’s stewardship, and when we see how superfluous (perhaps even a burden) we’ve become. This is the twin aspects of growing old and watching our children become more than we were: the good and the bad. There is joy in seeing their exploits, and sadness in watching ourselves whither. That’s when we feel our time has come. And sure, the desire to remain living is always present, and stronger than any rational, internal discourse. But when we allow ourselves to process what’s happening, when we aren’t feeling the limbic fear of our imminent demise, there’s a beauty and acceptance with knowing that it is natural to shuffle on, and that the world is going to continue getting better.

Imagine this process on steroids, because that’s what I think will happen when our creations are so much more capable than we will ever be.

There was a medical report just last week on how astronauts are more susceptible to heart disease, that being outside the protection of our atmosphere wears on their bodies. We might fix this with nanobots, or portable magnetospheres, only to discover the psychological damage that occurs when we are away from green plants and blue water for too long. We might fix this with some other advancement, and we might replace worn hearts and knees and lungs until we are half machines ourselves. But we will always marvel at the fully machine things we make, which tickle all the human empathy centers because of their looks, behaviors, words, and deeds. We will just be more fragile, less capable, more temporary. Kinda like what we go through now.

I think science fiction gets it all wrong to cast robots as evil armies. I think they will feel compassion for us, the way we feel compassion for our elders as they wind down toward the ends of their lives. Why would robots need to destroy with lasers what Time is already claiming? And why would mankind need to rise up against what we raised like our own?

There is a point in a child’s life when they pass from needing us to us needing them. It’s when we might go from worrying about KITT to KITT worrying about us. This process will happen with robots and artificial intelligence. It might be thousands of years from now, or tens of thousands, but at some point we will be convinced that their lives matter not just as much as ours, but more than ours. And it will feel natural to let them continue our collective existence by proxy, just as we do with our children. Perhaps we will stay on this wet rock as our sun runs out of steam, and our machine children will go off to travel the stars. We will be sad to see them go. We will ask them to call as often as they can. And of course they will, but it will never feel often enough.

The post Like Unto Children appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

July 21, 2016

Art, Science, and the Future of Work

Almost all technological and scientific progress is inevitable. New discoveries become possible due to the foundation of prior discoveries (and technologies). New technologies becomes possible due to the foundation of prior technologies (and discoveries). Both theory and experiment seem to find a time in which to emerge. They are buried things, and our thinking and tinkering erode the ground obscuring them.

Kevin Kelly

No one laid this out better than Kevin Kelly did in his excellent and must-read work What Technology Wants. Of course, had Kevin not written the book, someone else would have written one very similar. Because at its heart is this idea of technological and scientific inevitability, and that idea was out there, waiting to be discovered and written about. Kevin’s latest work, The Inevitable, continues this line of thinking to posit what lies ahead.

Even the greatest and most creative leaps are inevitable. The theory of natural selection and the calculus are both heralded as being way ahead of their time, and yet both were co-discovered in the lifetime of the people who get too much of the credit. The best a great mind can do is push us forward a few years earlier than we might otherwise hope. The collective mind — the accumulation of ideas and thoughts around the globe — lead us to the same place as singular genius, and often a mere half step behind.

History, then, becomes a tale of giving too much credit to too few people. More often than not, we pick someone out of the noise to represent the culmination of a breakthrough. Inventors and thinkers who market themselves (or are marketable) get credit solely when it deserves to be shared. But the appeal of the singular genius persists, because we love a story about people. Complex webs of interaction and precedent are more difficult to point to or understand. Far simpler to say Person A created X.

Art, perhaps, is the one area where things would go undiscovered without the individual. But this is because art has no underlying truth, waiting to emerge. It’s an expression of individuality. To lose an artist is a much greater loss than to lose a scientist, if scientific truths are inevitable. That undiscovered art may never be reproduced by anyone, anywhere.

But the calculus isn’t so simple. Science moves forward due to an accumulation of inertial mass. The more brains pushing, the faster we get where we’re going. There are some discoveries that are time sensitive: reducing our reliance on fossil fuels; saving species; getting off Earth; getting out of our solar system; curing disease and possibly even forestalling death. Every brain not pushing against this heavy cart might be thought of as a waste.

It is a trope of science fiction to lament the dollars spent on rockets we fire at each other when we could be sending rockets to the stars. All the wasted resources on tribalism and aggression that could be spent on discovery and self-preservation. There is a naive fantasy behind the Star Trek universe that humanity would find a common goal beyond. I feel similar frustrations with more immediately achievable goals.

We could have self-driving cars that free up our creative time and save millions of lives if we gave this advance moon-shot levels of focus and funding. We could have a world that runs on renewable energy if we had similar resolve in that arena. We could get off this rock and put eggs in another basket if we built rockets for the right reasons.

What’s crazy about this little list is that Elon Musk is working on all three, and he seems crazy enough to make it happen. And while he will get a lot of credit if (when) it does happen, we’ve learned from Kevin that these things are inevitable. There are other great minds pushing on this cart. There are thousands, millions of minds making contributions. It’s going to happen, it’s just a matter of when. Some of us are more impatient than others.

Jeff Bezos and Blue Origin

Elon’s SpaceX company is on target to launch over a dozen missions this year. They are recapturing their primary stages for reuse, which would help plummet the cost of launches. Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin has already reused a vertically-landed primary stage. This is a crazy accomplishment. The landing is one thing, but just as amazing to me is the ability for a private company to repurpose tech that has undergone such abuse, and must meet stringent QA processes, and then authorize it to fly to space a second time. At some point SpaceX will do the same. And Blue Origin seems bound to use its space tourism to finance a bigger booster, which will be a great competitor to SpaceX’s hauling capacity.

It all has the feel of inevitability. Darwin/Wallace, Newton/Leibniz, Musk/Bezos. It make me wonder if we landed on the moon a few decades earlier than we might have expected to, had technology unspooled at its own pace, simply because tribalism was turned for a single generation into a force for discovery. All the money and minds thrown into the problem were due to war, in this case with the U.S.S.R. That accumulation of minds was like the birth of singular genius, giving us a bit of a time jump forward. The Manhattan project did something similar with nuclear research, again due to the concentrating lens of tribalism.

When technology disappoints, perhaps it’s because of an accelerating leap that came too soon. We expect trends to continue along that slope, when what we really witnessed was a data point out along a future timeline. Space travel got us thinking too far ahead too soon, so that we’re now not appreciative of the strides being made in a sustainable and profitable manner. The majesty is gone by the time the mystery is solved. We finally get what we wanted right as we want way more or something else entirely.

I’ve written before about my hope for a jobless economy. A jobless economy would be a moon-shot worth pooling all our resources into. If we could automate our basic needs, so that the tools of automation were self-sustainable, self-repairing, self-reproducing, then every human being could live a comfortable life and choose their work based on passions rather than supply and demand. I know it seems like fantasy, but as a thought experiment, it’s worth entertaining. Because we are approaching this future asymptotically. It’s good to think about implications now.

Here’s what it would look like: Factories of robots build and repair the robots that plant, harvest, deliver, cook, and serve our meals. All run on nuclear and solar. All automated. You ask for a meal, and a meal is delivered. The raw materials used for the construction of the machines (and things like fertilizer) all come from land designated the commons. So when you ask “where does the money come from to support this?” there is no money. There’s the upfront investment in the technology and the first factories. After that, it’s all self-running. Money is today only needed for material resources, energy, and labor. In the future, the resources will come from the commons (beneath the earth’s crust, mostly), the energy will be renewable (solar, mostly), and the labor will be designed and built by itself. At this point we will have a spinning top that lasts for as long as our sun does. The capture of asteroids (already being considered) expands the commons and makes it an infinite-enough resource. No one works for food ever again. Unless they wish to, which is the whole point.

The same tech will supply shelter and safety as well. Houses will be built to order. Land can be bought, or land in the commons given. One of the grandest benefits that I could see from this would be time spent with family. Much of time apart is due to labor concerns (moving to where the job is). And our celebration of work, because of its necessity, will move to a celebration of passion, due to its creativity.

I used to wrestle with the primacy of art over science or science over art. You have on the one hand the fact that art is not inevitable while science is — art lost will never be regained; all science will be discovered. On the other hand you have the knowledge that science only moves forward with an inertial mass of minds behind it. But the mind experiment of a jobless economy solves this paradox: Artistic minds in the future are freed by a concentration of science today. Imagine the moon-shot where we tailored the economy and workforce to achieve the jobless state. Beyond this state, when AI is making discoveries and robots are making things, people will be making ideas. Artistic ideas, but also scientific ones and technological ones for fun. People will work with the machines because they choose to. We are already in this transition, which makes it difficult to mock. We count as a “job,” the creation of video games, the profession of athletics, the filming of stories, the writing of stories, the making of music. These have always been jobs, back to gladiators and bards, but more and more of the workforce is doing something creative rather than tending to our basic needs, because fewer and fewer of the workforce is needed to feed ourselves. Tractors drive themselves by GPS and harvest our crops. IBM’s Deep Blue comes up with recipes. Fast food joints are working to automate the ordering, cooking, and serving. It’s already happening.

I believe that it will happen fully. I think in two hundred years, most of our needs will be met for us. I think the transition will be difficult because we won’t understand what is happening, and we won’t be talking about it. I think we will blame immigration for jobs that are really lost to innovation. This doesn’t make it easier to bear for those in transition, but it would be easier if we really understood the forces at play. And even easier if we planned for this transition, embraced it, and saw all that was good about it.

People like Musk and Bezos are pushing us forward faster than we would go without them. Not as fast as governments go when they are creatively at war with one another, but hopefully fast enough. Perhaps one of these tech billionaires’ side investments in fusion power or quantum computers will provide another leap ahead. I think so. I think it’s inevitable.

Check out Kevin Kelly’s work. Start with What Technology Wants. The beauty of this book is that while it may have been inevitable as an idea, how it is written is pure art. No one else could have written the same book, and I don’t think anyone could have expressed these ideas any better. Also check out Elon’s latest plan for Tesla. Flipping brilliant.

The post Art, Science, and the Future of Work appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

July 15, 2016

Who I Am

I don’t think people change much. We change a little over time, but probably not as much nor as easily as we would like. We have our personalities, which our parents see early on, and we seem to carry these personalities right to the grave. That’s not to say our accumulation of knowledge and experiences and relationships aren’t important; it’s just to point out how imperceptible or not at all our core personalities change over the years.

I feel like the same person I was at age fifteen. I’ve gathered more raw knowledge and have seen more of the world and met more people than that kid, but if you put the two of us in a room today, we’d be like clones. Hell, it’s practically like this with me and my dad, and we only share half our genes. So much of who we are is inborn and inherited. My two best friends in the world are Scott and Chris. I’ve known Chris since I was 18, Scott since I was 20. We’ve all had a good 21+ formidable years since then, and these have been the real adult years, when we come into our own. But our conversations haven’t changed, nor have our personalities. Not much.

Some of my ideas have changed over time. I used to think guns were awesome. I grew up with guns, had my own guns since I was ten or eleven, and I’m still a crack shot. But I’m now disgusted by them and those who fetishize them. I’ll be posting something about this soon-ish. I’ve also changed my views on taxation. I used to think a flat income tax made sense, but I think the distribution of wealth has gone too far. Too much money is sitting, uncirculated, clustered at the very top, and this hurts the overall economy. (There are warehouses of art sitting in crates as an investment. This does not create jobs or help fund infrastructure. It’s a silly development in a world of widening income ratios, and there are many more examples like it). I think the top tax bracket should be closer to 80%, not 41%. I also think corporations should be paying a lot more in taxes by simplifying the code. A blog post about this is also coming soon-ish.

I’ve been sharing my views on sensitive topics for a long time. It used to be in a friend’s forum, or in person, or on my blog back before anyone read it. Those views are rarely simple or even consistent, and they’re often wrong. There’s a lot of hypocrisy in my mish-mash of opinions. I’ve been a hippy since high school. I worked in a Ben & Jerry’s, where the income ratio between the lowest scooper (me) and the owners (Ben and Jerry) was capped. I wore my hair long, a goatee, and Grateful Dead t-shirts. I also read Ayn Rand and thought we needed far less government. I volunteered with my church as an atheist. I owned a gun, but felt sick when I shot my first dove, and I never went hunting again. I’m a pacifist who’s good with his fists. I think it’s okay to terminate a pregnancy, but not okay to end the life of a serial killer. I live in nature, have always had a minimal ecological footprint, but I think attempts to preserve nature are foolish, and the idea that we can harm nature is ridiculous. I write science fiction, but I think the future will come slowly and look much like the present. I write dystopias, but I think tomorrow is going to be better than today.

Here’s the thing: I’m going to blog about the things I think with the hopes that I might think about them more deeply and perhaps even change my mind. This blog is mostly for me. It’s a journal that my mom can read (hey Mom). She will often email me after a blog post with something to say. Or my dad will call me to let me know his thoughts. I started this blog not as a published author, but as someone embarking on a journey of writing for fun. I’ve used the blog to advocate for authors, for the LGBT community, to promote other people’s works, and to write about my travels and my life.

The reason for this blog post is that I’ve heard from a few people over the years that success has changed me. Or that my views are no longer valid or shouldn’t be shared now that I’m a public figure. To which I say: bullshit. And I’d like to expound on that. I want to paint as clear a before and after picture as I can. Not just to set the record straight, but hopefully to help inspire those who have similar success or who also face these sorts of accusations. And also to let those who wish to know me to really get to know me. I try to be transparent in life. This is a continuation of that process.

Before I wrote my first novel, I paid cash for the house I lived in. My living expenses at the time were about $800 per month. Total. I owned my vehicle outright. I had long paid off my student loans. My house in North Carolina was 700 square feet. Yearly taxes on this house were roughly $300. My yearly insurance premium was under $400 per year. I made the economic decision not to have children. I had slowly saved up over $25,000 in the bank, which represented over two years of living expenses, which meant I was nowhere near the edge of my means. I’ve always lived WAY below my means.

This is all to say that I haven’t worried about money for a long time. For as long as I can remember, actually. And it hasn’t been because I’ve been rich, but because I haven’t shied away from living poor. I lived on a 27 foot sailboat in college. I had a $50 automobile. I didn’t have a toilet or a shower. I had a pot to piss in (literally). I’ve worked since high school, would only take money from family if I could repay it with labor (at a fair rate, preferably). My dad was legally obligated to pay for my college, but I paid it myself anyway, because it would’ve been harder to ask. Even when I was broke, I would alternate paying for lunch when I met my mom out. I cooked a lot of rice. For lunch, I ate the same PB&J every single day. When I was in the Bahamas, I did odd jobs for older sailors in exchange for food. I’ve never been motivated by money. I’m not motivated by it today. My wealth is all in cash, which is the dumbest thing I can probably do with it, but I’m not interested in seeing how much wealth I can generate. I’ve turned down 7-figure offers for books just to keep the ebook price low and maintain artistic control. I don’t know how to say it more clearly: Money hasn’t changed me. I was an outspoken ass and hypocrite before, and I’m one now.

A few examples, so you can get what my life is like today. I still wear the same clothes I wore before I wrote a book: cargo shorts and t-shirts. I’ve switched from Crocs to flip-flops, but mostly because I was getting small pebbles inside the holes that would then not shake out. My shirts have shifted from the green spectrum to blue, but mostly because Old Navy went that direction. My cargo shorts have gotten a few inches longer, but mostly because shoppers seem to hate their knees being seen? I don’t get it. I long for shorts when they were short. But that’s about how much I’ve changed when it comes to fashion.

I wash my own boat down. I gather my laundry up in a bedsheet, tie the four corners together, and walk it a mile and a half to a laundromat in Jersey City. I eat the same yogurt and fruit breakfast and smoothie lunch every day. The occasional fancy dinner? My ex girlfriend and I used to have the same attitude before I wrote my first book. Rather than go to Chilis once a week, we cooked dinner every day and saved up to go to a really nice meal now and then, like at Boone’s excellent Gamekeeper. We valued experiences more than things. We hiked every day rather than go to the theater, so that we could afford to charter a sailboat for a week in the summer. There were more sacrifices than extravagances. The same is still true. I take the subway, the bus, or I walk. Occasionally, I’ll UberX or Carpool, and it feels like I’ve rented a limo when I do.

Sailing around the world on a sailboat sounds glamorous, but is a lot of hard fucking work. Yesterday, I was pulling apart a toilet and putting it back together. And hotwiring an engine. It’s not an easy life. But it’s an amazing life. I think constant strife is a key to true happiness. I loathe comfort. Or routine. Most of the people who romanticize my life wouldn’t enjoy this life at all. And this is the same kind of life I was living when I was a broke college student. I paid $10,000 for that 27′ sailboat and lived on it for five years. Think about that. Do the math. The truth is, I’d be doing this no matter what, just on a different kind of boat, one that wasn’t as accommodating for friends and family. I was sailing and island hopping nearly two decades before I wrote my first novel. This is who I am. Very little has changed.

I recently wrote in response to an accusation that success has changed me, that my views have not changed, but how I’m viewed has. That’s not entirely true. Of course my views have changed. I’d never want to celebrate the calcification of my opinions. But they’ve moved along a trajectory that they were already on. I’ve grown more tolerant across the course of my life, and I started from a pretty tolerant place. I lost my religion when I was twelve, and I’ve been looking for answers since. Some of the things I’ve changed my mind on are gun control, invasive species, GMOs, and the environmental impact of cities. Just to name a few. But most of these changed before I started writing. I was a lot more opinionated on my blog prior to having any success. The only reason I’ve modulated my outspokenness at all is out of respect for publishing partners. I care about them recouping their advances. But I haven’t clammed up much.

I used to blog a lot about publishing, and those were political and controversial viewpoints as well. My view of self-publishing has become more generally accepted and embraced by others, so the advocacy is no longer as necessary. But anyone who has been reading this blog for the last seven years (god help them) will have read about homosexuality, religion, politics, and discrimination from the beginning. Back when I was unknown. What’s really changed is that when I post something people vehemently disagree with, they often think it has something to do with my writing career. It doesn’t. That’s something going on in their heads, not mine.

Here’s something that not many people reading this will get and most probably won’t fully grasp, but I am still a complete unknown. I know this and truly believe this. Even when I get recognized on the street, or meet fans with tattoos related to my works, I marvel at the unreal and surreal and do not incorporate it into my view of myself. Practically no one has ever heard of me. I’ve made no real contributions to society. I was more useful, as a human being, when I was a roofer. I look at my yachting career as a complete waste of oxygen. I look at my writing career as a weirdly high-paying hobby/passion. When I sit in a restaurant, ordering a burger and a beer, and I watch how hard the staff is working, bustling about, I feel guilty. I tip way too much. I’ve worked in food and beverage, and the knowledge that I’m earning more sitting there than I’m spending troubles me. It doesn’t feel fair. I pay all my taxes, and I give where I can, and it’s still not enough.

In the ways that are truly important, I’m a failure. I failed to make my last relationship last until old age claimed one of us. I’ve failed my parents by not returning that gift to a new generation. I’ve failed my readers by not providing all the sequels they would enjoy. I failed one of my dogs as she died in my lap in a canoe. I failed my other dog by not being with her today, raising her until her last breath. I fail the writing community by not advocating more, reading enough manuscripts, blurbing enough books, and in so many more ways. These are burdens that I feel every single day. There’s very little smugness here. There’s more shame than anything.

So that’s who I am. I’m irresponsibly traveling the world like a vagabond, just as I did straight out of high school (and to some degree did while still in high school). I’m not motivated by money or chasing more of it; rather, I’m walking away from the pace of output that brought me riches and could bring a whole lot more. I’ve given away most of what I’ve owned, setting it on the side of the road, or donating it, or sending it off to readers for a nominal fee, or leaving it with my ex. My sailboat has operated like a floating hostel, with friends, family, and strangers coming and going and taking bedrooms as their own for extended periods of time. I feel like I’m getting dumber every day (degeneratively dumber, not “I’m getting so wise because I know how little I know.” I mean, truly dumber). I feel like I have almost nothing to contribute either intellectually or creatively. I reluctantly blog, worried that someone might actually read what I write. I barely social media, other than occasional bursts on Facebook. I plan on doing even less and less as time goes on.

So for those who think success has changed me, this pacifist with a sailor’s salty mouth says: Fuck You. Which is exactly what I would’ve told you had you been rude to me before I wrote my first book. I’m generally a nice guy, and kind to strangers, and more prone to hug someone than argue with them. But seriously, if you think I can’t share my views because I wrote some stupid books, or you think I have an attitude borne of acquiring wealth, fuck you. I’ve always hated assholes like you. I’m pretty sure I always will.

P.S. Hey Mom, love you. Hate I missed the dinner party last night.

The post Who I Am appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

July 5, 2016

An Idea, Broken

Ideas for short stories and novels almost always hit me while learning something. I will be reading the newspaper, or reading a great non fiction book, or traveling somewhere exotic, when a story idea will pop into my head, with the general plot outline quickly unspooling after. At TED Summit, ideas were hitting me while in conversation with some of the greatest thinkers alive today.

I’ve been to a dozen or so conferences like this, and they have become story idea factories for me. Often, the technology or discoveries being discussed aren’t completely new to me, but the back and forth with someone who has a hand in these discoveries, or who offers a new perspective, is what generates the idea. It also helps to be around enthusiastic and creative people.

After FooCamp one year, I came home and had an outpouring of artificial intelligence stories. At TED this past week, AI played a huge role in many conversations, but we also talked about the environment, security, globalization, robotics, and the future of work. This has me leaping from the novel I’m currently working on to push an older novel idea forward. Its time has come.

But what I want to introduce here is my method for coming up with science fiction plots (though I believe the same method works across all genres). The method is this: Come up with a new idea, and then break it.

It’s tempting to write science fiction stories and have them be about a new idea, whether that’s AI, or a world where dogs can speak, or a galaxy full of interstellar travelers. Science fiction authors are generally enthusiastic about science, and so the temptation is to write about gizmos, discoveries, future societal structures, and the like. This sort of brainstorming makes for great ideas, but also for boring as hell plots. Once you have the initial idea, you need to break it.

The idea for embedded identification and currency is not new. Some intrepid folks are already experimenting with embedding chips into their skin. But it was only after listening to two BitCoin lectures, and while chatting with Kevin Kelly, that the image of a sack of dismembered hands popped into my head. Here was a visual worthy of a short story: crooks who peddle in left hands; doctors who offer underhanded (sorry) transplants; scar and pigmentation creams and gels.

This entire criminal underbelly popped into my head, an idea of embedded wealth broken, but as is my brain’s habit, I wanted to break it further. What happens when a man gets the wrong hand? Or the stolen ID comes with more than he bargained for?

This is a lesson that I believe to be critical in storytelling, one that it took me ages to figure out and has taken me longer to attempt to put into words. Because the magic of breaking ideas, and breaking them even further if possible, is threefold: The first advantage is that this new world becomes more believable by having the new idea established and mature. The second is that it makes the story, inherently, about people rather than just the ideas. The third is that you have tension in the first paragraph or page. Let’s look at all three advantages.

Why does the world become more believable? Because the characters in the world accept and believe the new idea. This is important in separating clunky science fiction storytelling from the smooth. When the new idea is mesmerizing to the characters inside the story, it feels like the reader has stepped into a World’s Fair from the 20s. Or is reading a popular science magazine from the 50s. GEE WHIZ! Whouldya lookat that?! Which might be how we feel, as writers, about our ideas. But if we present them to our characters like this, our readers will feel the same disconnect. And they’ll often stay disconnected.

In WOOL, the fact that people live underground is not remarkable to the people who live there. Neither is the idea of porters, or wallscreens, or how to bury the dead. The people of SAND don’t geek out over the tech of sand diving; they just want to know how to get rich or stay alive. In BEACON 23, there is nothing amazing or unusual about lighthouses in outer space. Writing about the commissioning of BEACON 1 would be boring, because the story would be about the unveiling of the idea. All the good bits happen once the idea is established, and the unintended consequences come into play.

The best stories have memorable characters more than whiz-bang ideas. This is what draws the reader in, the age-old hero’s journey. And it is how innovation interacts with human nature that unintended consequences arise. This is where science fiction excels, because it can serve as a warning, as a glimmer of hope, or as satire to the current human condition. In BEACON 23, I wanted to explore the consequences of solitude on someone who suffers from PTSD and needs, more than anything else, human contact. The idea of a lighthouse in space is intriguing: You have a human being as far removed from his kind as is possible. How can you break this idea? Place a human there who needs the catharsis of empathy and human touch. What happens next?

Which brings us to the third and final bit of magic that comes from breaking your new idea, and that’s the tension from the first page. Too often, writers end their story where the story should really begin. The climax should be the opening act. It’s the aftermath that brings all the confusion and conflict that drive a story forward. We need to see the character change, and that is not nearly as satisfying when it happens on the last page, through some deus ex machina intervention, as it is when we’re aware of the troubles from page 1 and get to see the protagonist struggle, fail, adapt, and overcome during the course of the story.

Take one of your story ideas and apply this technique and see what you come up with. We might imagine a few SF tropes to see how it works: Instead of a first contact story (mankind meets a sentient race for the first time), what if we meet the fifth sentient race in the galaxy, only to learn immediately that the other three races have had contact with this new race for many thousands of years. Why haven’t these other three races told us of their existence, among all the other secrets we’ve shared back and forth? What are they hiding? (Make the new idea established, break it, then break it further.)

With my AI story THE BOX, I took the idea of creating AI and made it well-established, to the point that this powerful technology was regulated and largely forbidden. Then broke those regulations. Then explored the worst-case scenario of breaking those regulations. I found it a lot more interesting and easier to write than a turning-AI-on story. Even when I wrote an AI-turning-on story in GLITCH, I was really writing about battle bots, war, and PTSD after talking with a friend who went to a championship finals with his battle bot.

Give your story layers, and give this technique a try. See if it works for you. Ideas are great. Shattered ones are better.

The post An Idea, Broken appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

June 29, 2016

TED Summit 2016

I’m currently in Banff at TEDSummit 2016. It’s only the third day, and already I feel intellectually and emotionally drained. The talks yesterday were fantastic, and I woke up still thinking about them and all the great discussions taking place outside the halls and during our excursions here into nature. A few that stand out:

A very brave woman from a certain middle eastern country stood on stage yesterday in complete darkness. The TED cameras were turned off, and the two thousand or so attendees were warned that any photographs could get her killed. This was repeated again so that we could really take it in. It’s sobering that this is the reality in more than a few corners of the globe, the danger of speaking one’s thoughts.

She came out on stage and explained how she has come out in the virtual world. She talked about being a woman and being gay in her home country. She is an activist through social media, but her family can not know she’s gay. She talked about her struggles and her strengths and the strength of the women and the LGBTQ community in her country. And the fact that they aren’t going away, that they refuse to give in, and that they are finding one another online and finding a power in their collective voices there.

Technology is having influences on individuals and groups alike. For some minority communities, it’s the only way to speak out safely and to find others in similar situations. It’s the only way to have a voice, both individually and collectively. But technology is having other influences. It’s a place to recruit extremists and to plan attacks. And more broadly, it can lead to misplaced anger. In a conversation with Rod Brooks, the founder of iRobot and Rethink Robotics, it was suggested that the employment effects of technology are now being blamed on immigration. Just as the Great Depression may have been caused as much by tractors and the displacement of agricultural workers, the tensions here in the States and abroad (like the UK) may be due to employment shifts that are much swifter than demographic shifts.

Another incredible talk came from a woman with myalgic encephalomyelitis, or chronic fatigue syndrome. It was one of the most powerful talks I’ve ever seen. Again, it came with a preamble and a warning. We were not to applaud at any time. Instead, we waved our hands above our heads like we would for someone who was deaf. Any kind of stimulation can be exhausting for someone with ME.

Watching Jennifer speak from her wheelchair, pausing to catch her breath now and then, laboring through both physical and emotional exhaustion, brought this disease to life. More people suffer from ME than MS, and the funding is sparse. A mere $5 spent per patient, compared to thousands per AIDS patient and hundreds per MS patient. Part of the problem with ME is that sufferers simply disappear from view. They crawl into darkness. It is an invisible but pernicious problem.

The other and more ruthless impediment is the shame and humiliation those with ME suffer as they are told there’s nothing wrong with them, that it’s all in their head, that they should just overcome the disease with a force of will. Because we do not yet fully understand ME, doctors look to psychological explanations. Jennifer tells us that it’s far better to say “We don’t know.” But the suffering is real. Jennifer will pay a heavy cost for traveling here from Boston, but she gives a face and a voice to the disease. It was a courageous display that brought me to tears.

There are themes that emerge with any conference like this. I’ve seen it before, and it arises organically from the issues boiling at the surface, that we bring together from all over the world. Brexit has been a regular topic, and AI has dominated many discussions. There are three talks this week on the blockchain, the technology behind Bitcoin, and the ways it can be used outside of currency. Some of these are going to be critical for artists, and I’ll devote an entire blog post to that. One speaker claimed that the blockchain is more important to the future of society than artificial intelligence, and he proceeded to make a decent case.

Beyond the ideas that percolate, and all the stories that are now begging me to be written, are the people. Friends I haven’t seen in a few years. Friends I bump into a few times a year and am able to pick up right where we left off. And then those personal heroes whose books have been brilliant guides, whose ideas have been sweet companion, and the chance to not just thank them but to hear what they’re working on now, what they think is next.

Possibly the best idea I’ve heard this week is the need to take conferences like this and get them further afield. The TEDx conferences are part of this effort. But last night, a thought occurred, one I want to work on or hope someone else would be interested in brainstorming with me. We wear these name tags here that reveal who we are, where we’re from, and a few topics we’re interested in. Even around town, outside of the conference, we tend to wear them. And they serve as constant invitation to join any conversation, mid-sentence, and listen or contribute.

Like a steakhouse where you turn up a token if you want more service, and flip it over if you would like to be left alone, I would love to see the use of these name tags in the wild. Open source them. Have them be more common. A signal that there’s an open mind here, one looking for debate, or an exchange of ideas, or just interested in hearing who you are, what you are thinking, how you are feeling.

I would wear one of these 80% of the time. Being able to walk up and introduce yourself to anyone at any time and commune is a recipe for expanding empathy, sharing ideas, pushing conversations upward and animosity downward. What do you think? Would you wear one? And what would your badge say?

The post TED Summit 2016 appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

June 25, 2016

A Crushing Defeat

Immigration reciprocity is nasty business. If you’ve ever been to Brazil as an American, you’ve seen this in action. It works like this: However difficult country A makes it for citizens of country B to visit, country B then enacts the same rules for country A. Which means going through an insane amount of work and sending off your passport just to get into Brazil, because we do the same thing to Brazilians. They adopt our rules to show us how punitive those rules feel.

Make no mistake: The fault is ours. It shouldn’t be this difficult to visit another country. Ever. You should be able to show up, present your documents, and your lack of outstanding criminal warrants — and agreement to follow local laws and pay local taxes — allows you entry.

If the same xenophobia that led to the Brexit also leads to harsher immigration policies and procedures, British citizens will likely suffer reciprocity from other EU members. Right now, you can drive the chunnel and go from England to France without stopping. Just like you can currently drive from Texas to California without having to get bureaucrats involved (not counting the produce police on the way into New Mexico). That ease of access will likely cease. Which is absolutely terrible, not just for human freedom, but for economic growth.

Imagine natural gas exploration taking off in North Dakota and not being able to get enough people through the red tape to take the jobs. The private sector is more flexible and swifter to pivot than law-makers. Hardening borders is terrible for economic growth. But it’s not just economics; imagine only being able to date someone in your home state because of the complexities of job requirements and immigration woes (I’ve recently gone through this with a girlfriend from the UK). These are the real-world consequences of protectionism and xenophobia.

What’s disgusting is that older voters lead the way with their intolerance, and they aren’t as greatly affected by their actions. They are moving out of the workforce. They’ve already married and settled with their loved ones. Geographic isolation is less harmful to those who have settled down; it’s terrible for those still looking for their place in the world. Which is why voters under 30 overwhelmingly chose to stay in the EU. It’s also a matter of subsequent generations being more tolerant and less hate-ridden than those who came before. Progress, as they say, happens one funeral at a time.

The Brexit has its parallels around the globe. Nationalism and isolationism are on the rise. What’s really amazing about the racism and xenophobia here in the US is that it’s completely unfounded. Between 2009 and 2014, the net flow between Mexico and the US was 140,000 Mexicans LEAVING this country. Our economic stagnation, Mexico’s meager economic progress, and family reunification, were all factors. Perhaps it’s fitting that the hero of this movement here in the States, Donald Trump, got his facts exactly backwards when he celebrated Scotland voting to leave the EU. His adherents get the facts exactly backwards as well. Opening borders with the rest of the world would not result in a stampede. It would result in a natural flow in both directions.

Racism is the root of this nationalism, plain and simple. If it weren’t, we’d see people picketing high school and college graduation ceremonies for all the looming jobs about to be stolen. We’d see intolerance toward pregnant women and kids in strollers for all the jobs these new Americans are going to steal. We’d hear more about these dastardly Canadians.

The xenophobes are not worried about population growth, not really. Population growth leads to economic growth. A newborn child and an immigrant are both going to consume and trade just as much as they work (more so, with debt accumulating over time). That means every new body is more jobs created through more spending. When you see an immigrant, see a shopper, an eater, a renter. Just like you do a newborn. The fact that we don’t see it this way says it all.

Look, borders are a dumb fucking idea. Lines on maps are necessary to a point, but not when it comes to immigration, the free flow of people, or the free flow of trade. These bureaucratic walls are only beloved by those who fear that the makeup of the populace will change (usually by growing darker). But it’s the next generation that has to live with the consequences of these protectionist schemes.

Let’s take the idea of Brexit a bit further and liken it to the United States fracturing. Imagine a different currency in all 50 states. Different rules and regulations. Our political leaders would waste more and more of their time debating trade deals, which would mean more lobbying from special interest groups who try to get import duties on everything they make, while reducing duties on the raw materials they need, with everyone else fighting for the exact opposite. He who provides the nicest steak (pick your bribe) wins.

It’s ironic to me that the small-government side of the political spectrum is all about the proliferation of governments. I have heard this argument that bureaucrats in Brussels are corrupt and self-serving, as if bureaucrats anywhere, at any time, have been anything less. The only way to achieve smaller governments, so that private sector initiative can move the world forward rather than backward, is to have fewer governments, not a lot more of them with smaller borders. To argue that the United States would benefit by being 50 separate countries is absolute lunacy. Just look at Germany before and after Bismark. Or Italy of the city states. Yet this is what the pro-Brexit crowd is applauding, especially once Scotland votes for independence and the EU breaks up further. They’re applauding the equivalent of the dissolution of the United States. That’s how fucking dumb their stance is.