Hugh Howey's Blog, page 11

January 19, 2018

The End of Bitcoin

No, I’m not talking about the recent crash in price, wiping out 50% of the value of something that shouldn’t have a lick of sane value in the first place. I’m talking about the very real and inevitable end of Bitcoin. It’s all about entropy and algorithms.

The number of Bitcoin is capped at 21 million. Once the 21 millionth coin is awarded, no more can be mined. That’s it. It’s a limitation built into the algorithm itself. Of course, you can change the algorithm, but then all the arguments of why Bitcoin is different go right away. Now you’re just printing money like the Fed, only you don’t have a continent of land and minerals to back up its value.

What’s more interesting to me is the fatal flaw of passwords. You have to protect your Bitcoin wallet passwords at all costs. Bitcoins are like bearer bonds. If you steal them, they’re yours. The rightful owner can’t get them back. And if you lose your password, you can’t retrieve them. There are already people freaking out because they mined Bitcoins years ago, when they were worth pennies, and now they can’t remember how to get their Bitcoins back. Not only that, but everyone who passes away without leaving their password behind means those Bitcoins are also gone forever. Poof.

Bitcoin was designed to fight inflation. The growth rate is capped by making mining more difficult over time, and the total number of coin is capped at 21 million, so a deflationary period is to be expected. What wasn’t accounted for in the algorithm (or any of the crazy hype about blockchain) is human fallibility. We can’t remember our passwords. We also refuse to plan appropriately for our deaths. We are going to keep losing Bitcoin, and it is going to go to the grave with us, until there is no Bitcoin left. This ratchets in only one direction.

The end of Bitcoin is as sure as the winking out of our sun, only it’ll happen a whole lot sooner. The max cap of Bitcoin, and the entropy of human recollection, mean that Bitcoin’s days are numbered, not just as a bubble, but as a thing with any kind of existence, real or imaginary.

If you write your passwords down, they can be stolen with no recourse. If you don’t, they’ll be lost for good one day. I didn’t think it was possible, but somehow the Winklevosses are going to look even dumber in the sequel.

The post The End of Bitcoin appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

January 6, 2018

Happy New Year

I’m sitting here in Tasmania, on the other side of the world from the small farming town in which I grew up, reflecting on the wild adventure my life has become. This past year was one of the best of my life, even as it contained some of the most difficult things I’ve ever wrestled with. My father is bravely battling cancer. The country I love is taking what I feel to be massive steps backwards. I’ve spent many a dark hour thinking about what’s slowly slipping away.

But I also think about all the good to come. The next generation of young adults are more amazing than the last, and this trend seems universal and without end. The world and my country have survived far worse. There are great trends to focus on, such as the imminent death of coal and the ascension of cheap solar. Or the healing of the ozone layer. There are always problems to fix, but we should appreciate the problems that we solve along the way.

I spent a month of my year in the Galapagos, and my father joined me. We swam with giant sea turtles and hiked lava tubes with blue-footed boobies. This was just a year after sailing across the Atlantic Ocean with my dad. How many kids are this dumb lucky that they get to spend forty days straight with a parent — and a best friend — fulfilling a lifelong dream?

There is always good in the bad. I wrote a short story about this once. In the wake of losing my beloved dog, in one of my darkest of places, I began a novel that would eventually be about the redeeming power of hope. When I sign copies of WOOL for readers, I almost always write “Dare to hope” inside. The original self-published version of WOOL was dedicated to: Those who dare to hope. I think it’s the bravest thing we can do, have hope. 2018 should be a year in which we remind ourselves of this.

There is always good in the bad. I wrote a short story about this once. In the wake of losing my beloved dog, in one of my darkest of places, I began a novel that would eventually be about the redeeming power of hope. When I sign copies of WOOL for readers, I almost always write “Dare to hope” inside. The original self-published version of WOOL was dedicated to: Those who dare to hope. I think it’s the bravest thing we can do, have hope. 2018 should be a year in which we remind ourselves of this.

Bright days are ahead. They will follow nights that seem cold, dark, and lonely. This is how it’s always been.

I hope we can remember to share the good moments without it seeming that we aren’t aware of all that’s grave and serious. Laughter, joy, and positivity are critical now more than ever. Michelle and I are working on a website to celebrate just these things, a place of respite and peace where deep breaths can be enjoyed, quiet contemplation pursued, positivity embraced. It’s not a retreat from the world and its serious issues, but a way of regrouping, of fortifying ourselves for the good fight, and for appreciating the progress already made.

What I appreciate every day of my life is you. Not a single day goes by on Wayfinder that I don’t pause and appreciate what your support and readership have meant for me. It has made it possible for me to fulfill a lifelong dream of sailing around the world. Right now, that crazy book I wrote so many years ago, is in the top 100 on Amazon, still selling strong, still gaining word-of-mouth, still finding new readers who dare to hope. Thank you for that.

I look forward to the adventures ahead. I just put the finishing touches on my first draft for a WOOL TV pilot. An embarrassment of amazing offers have poured in, after getting the adaptation rights back from Ridley Scott and 20th Century Fox last year. This project was always meant for TV. I just never had any hopes of anything actually getting made. I went with a big name, and a big offer, for the big screen, all because I never thought anything more would ever happen. I was too afraid to hope.

I’m going to try harder in 2018.

Thanks for everything. For the rest of January, WOOL will cost a measly $1.20. This novel has probably never held more societal significance than it does right now. I look forward to the new connections it makes with readers, the new friendships it brings, and the adventure it might take us along very, very soon…

Thank you for everything, and have a Happy New Year,

Hugh Howey

The post Happy New Year appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

November 27, 2017

The Value of Reading

Five years ago, I made the novelette WOOL available for free. Permanently. This is the short story that launched my career as a writer, and I wanted to make it available to as many readers as possible. When I discount my books, or make them free, I think about conversations I’ve had with authors about how we value our works. What I think is just as important as the value we place on our art is the value we place on its enjoyment.

Five years ago, I made the novelette WOOL available for free. Permanently. This is the short story that launched my career as a writer, and I wanted to make it available to as many readers as possible. When I discount my books, or make them free, I think about conversations I’ve had with authors about how we value our works. What I think is just as important as the value we place on our art is the value we place on its enjoyment.

Not everyone can afford to sate their reading habits. Library cards, used bookstores, and friends’ bookshelves are part of how we get by. There’s also Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited program, where most of my works can be found and read by KU subscribers. For everyone else, I try to keep my ebooks priced as low as possible. It’s not that I don’t value my craft; it’s that I value your readership.

[image error]

This Cyber Monday, I’m blowing out my prices even further. Why? Because I can. The first novel I ever wrote, and still one of my favorites, is Molly Fyde and the Parsona Rescue. It’s free all week. Grab it now and save it for later. I lowered the price on the rest of the series to $2.99 for each book. These are rip-roaring sci-fi operas that millions of readers have enjoyed. You can get them all for the price you’d normally pay for a single novel.

The WOOL series is also on sale. Shift and Dust are an insane $1.99 today only. And so is the WOOL Graphic Novel. As is one of my personal favorites, the absolutely disgusting and poetic I, Zombie. The Sand Omnibus novel is also $1.99 for a day only. Beacon 23 is only $1.49! The Hurricane and Shell Collector have been knocked down to $2.99. As is fan-favorite (and my sister’s favorite) Half Way Home. You can pretty much get my entire body of work for the cost of a single hardback.

On Friday, I noticed a surge in sales as readers unboxed their new Kindles. But even if you don’t have a Kindle, you can read these ebooks on pretty much any device with the Kindle app. Or you can order the paperback or audiobook if you please. It’s all up to you. If you’ve already read them all, feel free to share the news with a friend, or go see what other deals you can find. Most of all, keep reading. It’s what I value the most.

Also: Some very cool news coming your way soon about a new project I’m cooking up. It’s been inspired by the unbelievable reaction people have had to my Wayfinding series. This is a collection of works that I haven’t promoted much; it’s been a passion project that has somehow found its audience on its own. The first part of the series is free all week, and I look forward to sharing more about the ideas you’ll find in these books. Stay tuned!

The post The Value of Reading appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

November 10, 2017

The Devastating Consequences of Blind Worship

Living on a boat is a life of constant troubleshooting. There are always at least a dozen things not working on the boat, and often one broken thing leads to several cascading issues. One electrical short can create a nightmare of confounding variables. It reminds me of my years spent repairing computers at Tandy. When a computer system is a mess, what you hope to find is a single issue that clears up many of the problems in one fell swoop. When I’m overwhelmed with a number of things that need fixing, I look for a common cause to sort out first.

A lot of people feel overwhelmed right now, people on both sides of the aisle. Our society feels like a confusing and jumbled mess. I say this as an optimist, as someone who reads a lot of history and sees all the amazing progress we’re making. But I’m also an idealist, which means our progress never comes as quickly as I’d like. I know that we’ll fix almost all of our issues eventually — the arc of history points in this direction — I just believe the quicker we hasten toward that goal, the more suffering and discomfort we’ll alleviate along the way.

Toward this end, what are the handful of primal causes for many of our issues? Can we find an electrical short here or there, or a bug in our programming, that will sweep away a lot of problems all at once? I certainly think this is the case. I think humans are simpler than we often assume. We were designed or evolved (take your pick) for a more primitive time. Drink, Eat, Sleep, Defend, Reproduce. All of our complexities spill out of the interplay of these very simple drives. The problem is that many of the things that used to benefit us in the past cause us a mountain of trouble today.

I write about these causes and effects in my Wayfinding series. This blog post is a preview of an upcoming entry, but writing the piece is proving so useful to me in understanding current events that I want to get the gist of it out now. The gist is this: Blind Worship had enormous advantages in small tribal societies, but it is leading us wildly astray today.

Blind obedience makes sense in small tribes, when you need to coordinate and act as a group. The tribes that adopted or evolved this ability would win out over tribes that were fractured. Sure, there’s a chance the group is led astray and makes a mistake. But the group that’s always bickering, debating, and in-fighting stands very little chance of making a winning move. They have themselves to overcome before they can compete with others. You can think of the tribe with blind worship as a single cell that has roped in its mitochondria and cytoplasm to function as a holistic whole. The tribe without blind obedience is wrangling internally, as external threats plan their next move.

Like most of our primal impulses, what made sense thousands and millions of years ago no longer serves us well today. The legacies of these impulses now waste our time, rile us up, fill us with anxiety and depression, and have us looking to the wrong causes to solve our ills. Blind worship of tribal alphas, both female and male, are a massive problem, one we need to be aware of, discuss, and work to fix.

We need to train ourselves, encourage each other, and teach our kids to not look up to people. We need to learn to look across at one another. Learn from each other, admire the accomplishments of others, celebrate our mutual weaknesses, and do it all from an even pool that more accurately reflects the complexity and messiness of humanity.

Blind Worship is the root cause of many of today’s most disturbing headlines. When we worship celebrities, who are just actors reading lines in front of a camera, it gives them power that they do not know how to wield and that we do not know how to defend against. Would an actor tolerate a stranger molesting him or her? No. But when it’s another actor with a bigger name, someone they look up to, they are often frozen to resist. Would a child tolerate a stranger fondling them? Not as easily as when it’s a priest, who they’ve been told can do no wrong and to look up to and respect.

Culture arises from the interplay and contribution of a million little decisions. Rape culture arises the same way. It’s the inaction of friends when someone says something abusive. It’s a parent being proud of their teenage daughter for winning the affection of a much older politician. It’s the fear we all have to talk about these things with our children, our parents, our religious leaders, our spouses, and each other. My own hesitation to write about this on my blog contributes in some small way to rape culture. Silence is the worst killer, because it’s so innocuous, so difficult to notice, and so easy to add to.

I don’t know if it’s supposed to be derogatory or not, but I’ve been called a Social Justice Warrior in my social media feed a time or two. Social. Justice. Warrior. Three words that all sound awesome. I’ll take it. But sometimes being a social justice warrior can itself contribute to rape culture. When we jump down the throat of someone who is trying to talk about these issues, and saying and doing positive things, but they left a letter out of LGBTQ, or they used the wrong pronoun, we are creating a culture where people are scared to speak up for fear of getting shouted down. And in that silence rape culture thrives. So that’s something to overcome. We need to have this discussion, even as we brace for those looking high and low for some way to be offended.

I know someone who works for a company rife with rape culture. One of the biggest names in the sexual-molestation news right now is associated with the company, and employees are in a tizzy about how to handle the new allegations coming out every day. The few who have spoken up in the company are being hounded for it. People higher up the chain of command do not want to believe the accounts of a dozen victims, and an admitted reason for this doubt is the power the abuser wields. This is how rape culture thrives. It’s clear as day.

Here’s the thing about blind worship and rape culture: We all contribute to it. When we fawn over a celebrity, we add our oohs and aahs to their collective power. The power of that person’s professional and social connections all depends on our blind obedience. It will be almost impossible to do away with this effect, but I don’t even see us trying. Instead, we all do the very wrong things that make the problem worse.

We tell our children to respect adults. Why? We should teach our children to respect themselves. We should teach them to respect those who respect others.

We teach our kids, and we tell ourselves and others, to blindly follow our religious leaders. Why? We should challenge our religious leaders so they can help us unravel the mysteries of our actions and the contradictions of religious texts and human experience. If they are wiser than us, let’s make them prove it. Challenge them. Question them. Do their answers make sense?

We tell ourselves and each other that actors are brilliant. Why? Because they’re good at pretending to be someone else? At reading lines that someone wrote? Yes, their craft is difficult, and we should applaud when it’s done well, but that applause has nothing to do with who they are as a person. That requires digging deeper. The question I have is why we don’t similarly extol the brilliance of doctors, scientists, farmers, and bricklayers. Is it because we aren’t inundated with their faces on our screens? Does blind worship require us to first recognize a person’s visage? What bits of our internal wiring are not prepared for a billion of us to recognize the same face, and all add to their collective worship? Because that piece of crossed wiring is leading us astray.

Trump is president largely because of blind worship. His name was already a brand, and his face became even more recognizable through reality TV and the inordinate amount of coverage his campaign received. This worship is so strong that he can reverse every position that got him elected, and his base does not shift. He’s an actor reading lines. No one cares about the content. We are programmed to follow the alpha male, to not doubt their decisions, because this gave us power as a tribe, the ability to compete with other tribes, to move as a single cell, the way flocks of birds find safety in numbers. It worked so well for millions of years that we remain imprisoned by this impulse today.

Every day, we should work to untangle our blind worship of others. This should be an active pursuit, like the flexing of a little-used muscle. We should elevate ourselves and everyone around us to the same level, as we lower our blind positive esteem of strangers. This does not mean we should not admire those who deserve it, but we should think long and hard about what we admire and why. Do they make the world a better place? Do their actions inspire us? How do they treat others? Do their words and points make sense? And then we should remain vigilant, continue to challenge that person and ourselves, and be open to changing our esteem in a moment.

We know that this works, the changing of culture through the application of a million tiny forces. We changed the culture of cigarette smoking from something cool to a pariah, and we did it partly through smart legislation. We made it illegal to advertise a legal product on TV, in magazines, and at sporting events. That decision, to regulate a legal product, will save millions of lives. Culture can shift, but we need to first recognize where our culture is wrong and what we hope it will become.

Perhaps the most controversial viewpoint that I hold today is that the blind worship of our military leads to senseless slaughter. When we thank everyone for their service, and salute anyone with a uniform, we create a death culture to go along with our rape culture. We create a culture where kids see us perk up at the sight of anyone with an assault weapon. For generations, this has been going on. Is there any wonder why those kids grow up to lust after AR-15s? Is there any surprise that the country with the largest military, a country where not a single politician and very few citizens speak up about our fetishizing of this military, is now the country with the most guns?

We all contribute to this. Soldiers deserve our pity, not our respect. We should feel sad that they exist, that they are necessary. We should recognize that the world can remain safe with far fewer of them. We should want them home, moving into civilian life, getting therapy for what we’ve put them through. Death culture has got to end, and it ends by stopping our blind worship of everyone in uniform. We don’t know them on an individual level, any more than we know actors on a stage or athletes on a field.

How many athletes are forgiven for unspeakable crimes? Spousal battery. Animal fighting. Rape. Assault. Murder. Our worship of celebrity athletes allows them to continue along these destructive paths. It’s only when they seem to disrespect an object of our even greater worship that we criticize them. Everything wrong with blind worship is found in this paradox: a rapist standing with his hand on his heart is a hero; the soldiers on honor guard who killed children overseas is a hero; but the man on his knees, thinking about his fellow citizens killed on the streets, is somehow a villain.

Athletes, actors, elders, priests, soldiers, politicians, millionaires, CEOs, doctors and lawyers, none of them deserve our respect simply for being these things. They earn our respect with every action and word. Just like everyone else. I think this short in our wiring leads to an enormous amount of heartache and societal destruction. A lot of the tribalism and in-grouping and out-grouping arise from this single primal cause. We give too much power over these people who are strangers to us, and that power pervades society like a fog, making it more difficult and dangerous for victims and witnesses to speak up.

It’s easier said than done, right? How do you ask a sports fan to not get goosebumps when he sees a star player on the field or out on the streets? How do you convince someone to not date an actress or an athlete by saying it won’t change their lives, when it most certainly will change their lives? How do you defy your boss when we all know that who you know leads to promotion, wealth, and power? How do you get a believer who wants to avoid going to hell to dare doubt their preacher?

I contend that it happens gradually. We spiraled out of control, and now we need to slowly spiral back down to earth. It comes through a million little decisions and interactions. It begins by breaking the silence and by changing the existing noise to a different channel. If you agree, and these points make sense to you, or you have your own twist or something to add, then I urge you to share this or your own thoughts with everyone you know. I urge you to work every day to look up a little less to people you don’t fully know, and elevate more those whom you do. Those who truly deserve it.

You can start with me. I’m a hack who wrote some bestselling books, but that tells you jack all about who I am. Assume I’m the worst. I’m certainly no better than you. But I do believe in the rightness and logic of my thoughts here, and I think we can make the world a better place by applying them in our daily lives and our interactions with others. Judge these ideas and take them, make them better by adding your ideas, find something to agree with or critique here.

Remember that progress is made through doubt, not surety. Doubt your elders, your priests, your celebrities, your soldiers. Doubt the biases we’ve built up over the years. Teach our children to be skeptics. Try and learn for ourselves how to be skeptical. Let’s reel in these primal impulses that have led us astray and march forward on an even plane of mutual and well-earned respect. There’s a better culture in our future no matter what; I truly believe this. It’s only a question of whether we get there late or early. I say let’s hurry the fuck up.

The post The Devastating Consequences of Blind Worship appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

October 22, 2017

This Needs to End

A second Hurricane Harvey swept across the country last week, leaving behind anguish, confusion, and a flood of tears. The Harvey Weinstein story follows closely after the Bill O’Reilly story, the Roger Ailes story, and the Bill Cosby story. Hollywood loves nothing more than remakes. But this story has got to end. Now.

At a conference I attended this past weekend, several attendees shared their experiences in Hollywood’s culture of rape and harassment. Their confessions were met with sadness, anger, support, hugs, outrage, tears, and most importantly: hope. It feels like the terror and abuse that women have suffered for thousands of years may be coming to a head. Powerful men who abuse that power are starting to see consequences. But this alone won’t be enough.

The #MeToo hashtag is trending again, after actress Alyssa Milano revived it on Twitter with a call for anyone who has been abused. What has followed has been a chorus of voices like a gathering wind. We are at Category 5 levels of fed-the-fuck-up. But our outrage alone won’t make it so that no woman will ever again be harmed; the culture that allows and ignores this has to come crashing down so that these stories become the exception rather than the norm.

There are things we can do. Things men can do, women can do, parents can do, young adults can do. It starts with this conversation we are now having. It starts and ends with our voices. This movement is 100% the result of women who have the courage to speak up. We need to make sure we build a climate in which they feel safe for doing so. These recent high-profile firings help. The fact that we are now believing these women and applauding their courage helps. For too long we have doubted their stories. For too long the consequences have been worse for the victims than the abusers. That needs to change.

Speaking up is the hardest thing to do. There are a million reasons to stay quiet: fear of losing a job; the shame of being victimized; the confusion of what in the world happened and why; the lifelong inurement of a million small abuses heaped up until the horrific almost feels normal. Some of these fears keep those who witness the abuse quiet as well. More men and women who see this happening need to have the courage to speak out. And there’s a truth we need to accept and have a conversation about.

The truth that we need to confront is that men are creeps. We are all creeps. Every man has the potential to abuse women. Every man. It’s the way we talk about them from our teenage years on. It’s the way we leer at them, or turn our heads to check out a stranger on the street. It’s the way we make women feel uncomfortable walking down the sidewalk, so they have to stare straight ahead, even as they can feel our eyes on them, and they think to themselves, “Don’t look. Don’t look. Just keep walking.”

We all wish the world was a certain way — a safe world where evil is the exception rather than the rule — but wishing will not make it so. Only action and communication will. The reality of the world is this: rape is common and sexual abuse is rampant. This is a fact. The statistics on college campuses alone are sobering, and these do not capture the full extent of the problem. One in four women will survive rape or attempted rape while in college. ONE IN FOUR. College campuses, where the privileged and progressive supposedly gather.

Or how about the firestorm of rape that follows troop movements? The allies in WWII raped their way through Germany, with hundreds of thousands of “heroes” abusing their victims from a position of power, taking advantage of those they were meant to assist. A large part of the problem is that we lionize those perpetrating rape. It’s sports stars, CEOs, troops, fathers, priests, coaches, uncles, all the people we are told to respect.

How about we try to respect women for once? Just this fucking once. And then let’s make that respect a habit so that it lasts. So that this hurricane doesn’t sweep by, and we clean up after it and put our ugly houses back in order. Let’s rebuild from the ground up and try something new.

Men, try to understand that your advances are NOT FUCKING WANTED. Just because you want to have sex with anything that moves, understand that women are far more selective, and that your assumption should always be that they don’t want it. They’ll let you know when they do.

Don’t honk your horn at women on the street, or call out the window at them, or whistle, or make catcalls. Mock your friends who do. Have a talk with them. Let them know that’s someone’s daughter, mother, sister. Make your friend or co-worker feel like shit when they crack a joke. If you even see their eyes wandering, or one of those knowing grins, tell them to keep their eyes to themselves. Tell them this isn’t cool. It isn’t right. These little habits should be treated the same as a racial epithet.

It sucks that parents have to have these conversations, but I think they do. Every daughter needs to hear that men are creeps and that they should stick up for themselves. They need to know to expect this behavior, and to practice what they’ll do when it happens, so they don’t freeze up in shock. We practice safety drills in other walks of life for this very reason, so that our response to danger is an ingrained habit. Stop drop and roll. Know the nearest exit. Brace for emergency landing.

From the earliest age, girls need to be taught that every male is a potential predator. It doesn’t matter how cute, or successful, or good at sports, or wealthy — the very things they are going to be attracted to are the things that allow men to feel powerful and abuse that power. Every male is a potential threat, a grenade, a landmine. If you’re a guy reading this and you are offended, fuck you. It’s time for us to be uncomfortable. It’s long past time. I’m okay with every woman assuming the worst about me if it means they’ll feel safe. You should too. If you’re not willing to feel that way, then you’re part of the problem.

Girls need to know that when something happens, it’s okay to talk about it, to press charges, to demand repercussions. Which means it falls on us to make sure there are repercussions when something does happen. The judicial system and the public sphere need to rally to this cause. Serial rapists like Bill Cosby should not walk free. Our adoration of men in power should be seen as a danger sign, not a free pass. It’s that adoration and trust that allows much of the abuse that happens. Men feed on their positions of power. We shouldn’t be surprised when a coach, celebrity, priest, president, CEO abuses someone. Didn’t you hear Trump brag about this? Power and wealth have to become warnings, not smokescreens. We have to hold these people accountable.

Don’t ask why women haven’t spoken up sooner. It’s hard to admit to being abused. I know. You are ashamed, confused, scared. There’s a wild mix of emotions, unique to each case, and you cannot understand someone else’s victimhood. No one can. Each case is different. But it’s not uncommon for women to want to control the narrative to feel better about what happened, maybe even try to convince themselves they weren’t a victim. It can take years to know you were raped. I know. And when you realize it, you won’t know who to tell. And you’ll have seen over and over how some other accuser can have their life ruined while the abuser suffers nothing. Ask Monica Lewinsky and Bill Clinton how they’re faring.

The abuse isn’t just between strangers, not by a long shot. It’s between family members, co-workers, fellow students, and those in courtship. Hey guys — SILENCE means NO. The only thing that means yes is yes. I’ve been too paralyzed to stop abuse before, both while experiencing it and while observing it. The only way to make sure you aren’t a part of the problem is to check in with partners at every new step along the way. Ask permission before you touch someone that you’re dating, before you even hold their hand. I promise you that it can be romantic. Check in as you lead off first base, thinking about second. Even better — let her be the baserunner. Slow the fuck down. Give her time and space to let you know you’ve gone too far.

The other part of this conversation that we must have is the biological underpinnings of our worst behaviors. Evolution predicts this culture of abuse and rape. Belief and faith in gods does not. Raising our kids, and creating a culture, in which we believe in the divinity of human beings gets us in trouble. Evolutionary theory warns us to expect an imbalance in sexual urges. The reward to men for impregnating a dozen women is dozens (and then hundreds, and thousands) of copies of that drive as their DNA is passed along. There’s very little physical cost in the labor and upbringing of those children. We see this impulse throughout the animal kingdom.

The cost to women is nine months of pregnancy, a painful and dangerous childbirth, and huge expenditures of time and resources in the upbringing of the child. This is why women are pickier than men. It’s why they don’t want your advances. Men can’t seem to grasp this; we dream of the day that a woman sees us on the street and asks us for a quicky. Our y-chromosome-diseased brains can’t conceive of a woman’s brain wherein this is not okay. So we need the constant reminder. We need it early and often. Mothers need to tell their sons what it feels like to be a girl. Fathers need to warn their daughters what it feels like to be a boy.

Is it uncomfortable to confront these truths and have these conversations? Hell yes. Are there exceptions to these accusations of manhood and womanhood? Of course. Should we continue to endanger women because of our discomfort? Hell no. Should we continue to endanger women because someone out there says they are male and they’ve never had bad impulses? Fuck no.

Almost every woman has a #MeToo story. Almost every single one. That failure is on all of us. We have to admit that this is a problem, commit to building a better environment, and continue to speak up. We have to keep the conversation going. It should be a conversation that every child hears and hears often. Do not trust those in power. Do not trust men to know proper boundaries. Speak up when you’re even mildly uncomfortable. Humiliate those who are attempting to humiliate you.

And for men: Understand how unwanted your advances are — how terrifying and revolting they are. Learn from an early age how to treat women with respect, how to be wary of any power or leverage gained in life, how to speak up and humiliate your friends, colleagues, and superiors when you see them crossing any line. We should have a zero-tolerance policy for this. It can be done. We’ve made progress in shaming smokers, and those who drink and drive. We can have the same impact on sexual abuse.

My heart breaks for every woman who has endured this. My heart breaks for every woman I’ve ever made uncomfortable. I hope we can all do better by you. I hope we can build structures that make us impervious to these thoughtless, ugly, terrible hurricanes, until we run out of names for them.

The post This Needs to End appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

October 11, 2017

If You Like Bookstores…

I’ve spent a good chunk of my life in bookstores. When I was a kid, I made loitering in bookstores an artform. There were holes in the carpets of my local Waldenbooks in the shape of my butt. Later in life, I practically lived in the Barnes & Noble my mom managed. That lasted until I started working in my own B&N throughout my college years. After a career in yachting, I worked in an indie bookshop while working on my novels.

I spent much of these working hours dreaming of opening my own bookstore one day. I had a vision of what a bookstore could be. When I worked in my last bookshop, Amazon was already the 900 lb. gorilla in the bookselling biz, but I knew there was a way to coexist. People still wanted to wander in and discover something new to read. Curation and physical browsing were the advantages of small shops. My beloved Waldenbooks went out of business because of the failure of their parent company. I blogged years ago that this was a premature death. I also blogged about my ideal bookstore. I thought I’d have to build it one day.

Thank goodness, someone beat me to it.

On 34th street in Manhattan, between 5th and 6th, there’s a bookstore like no other. If you think Amazon’s foray into bookstores is a bad idea, or a loss leader, or just a place to showcase their electronics, or a fad that will crash and burn, you are wrong, wrong, wrong.

I didn’t quite know what Amazon’s play here was. I didn’t know what to expect when I dropped into the store. What I found was a revelation. And if you’re traveling to New York, you should add this shop to your to-do list. If you love bookstores, you’re going to love what Amazon has built.

Every book in the store is face-out. Every book in the store has a 4+ star review average. The shelf talkers (those little cards beneath the books) have a blurb from an online customer review. There are no prices on the books; you pay the current price on Amazon, which is almost always lower than the list price. Both times I visited this store (and I went to the one at Columbus Circle as well), the place was packed. These shops are going to make Amazon money; they are going to sell tons of books; they are going to become the recognizable bookstore chain across the country and probably around the world.

You know it the moment you step inside.

The hallmark of a successful bookstore is simple: It pairs readers with books they’re excited to read. What Amazon has done here is nothing short of brilliant: They’ve reduced the number of books available to the shopper. Where B&N and Borders would assault you with choices (and yet rarely have the particular book you were looking for), Amazon is going against the grain of their online bookstore, all while leveraging the big data mined from its online shoppers. The paradox of choice is that it disinclines us to choosing at all. Research shows that too many options causes shoppers to walk away empty-handed. At this shop, it feels like you can’t lose. Every book is selected to please. And Amazon knows better than any other bookseller which books are pleasing readers the most.

One of my favorite sections in the store reminds me of the “also-boughts” on Amazon.com. You know, the books suggested beneath whatever book you are currently browsing. The way they laid this out is brilliant: you’ve got a column of widely popular books on the left side of a bank of shelves, and on the rest of each shelf you’ll find several books you may not have heard of that are similar, or that share a theme. If you’ve read any of the books on that shelf, the other books will probably appeal to you.

This was my job as a bookseller for years. A customer would come in and say they loved THE HUNGER GAMES, and I would walk them to a book that I liked that I felt was similar. My skill at matching book and reader depended on my breadth and depth of reading. In the Amazon bookstore, you’ve got millions of people walking you through your shopping decisions. Every customer review, and every purchasing decision have gone into the curation of this store. On top of this, there’s an editorial staff making decisions with fewer of the biases of a New York Times bestseller list, and less of the corporate ills of merchandising dollars. Just. Great. Books.

Oh, and some questionable ones:

There’s a great children’s section that takes up an eighth or so of the store, with comfortable carpet for young butts to wear holes through. There are chairs to sit in to read with a loved one on your lap. There are unique sections with clever themes, and a New York section in this store, so some of the local curation that B&N never got right. The devices, of course, are here, but what amazed me is that they’re less intrusive than most of the Nook spaces I’ve seen in B&Ns. And far fewer games and toys. This is a bookstore built by people who love books. Cynics often accuse Amazon of not caring about books, and I challenge them to visit this store and cling to that myopic view.

I used to give a talk about the history of bookselling, and I closed the talk with my rock, paper, scissors theory of bookstore disruption. In this theory, small bookshops were disrupted by big box discounters, whose selection and pricing advantages were too much to compete with. Curation was not enough to retain customers who wanted better selection and lower prices. Then Amazon came along with far greater selection and even lower costs, and the big box discounters were hammered. This has led to the resurgence of small bookshops with their expert curation and physical locations.

The Amazon bookstore changes everything. Now you’ve got even better curation, but with the same online prices. You’ve got a shop where no customer loyalty card is needed, because the register knows you’re a Prime member the second you swipe any card you’ve used on Amazon. You’ve got a bookstore that will improve your online recommendations even as you shop offline. Perhaps the best part for me, as someone who is looking to discover new books that I’ll read on my Kindle later, you’ve finally got a bookstore that encourages you to whip out your phone to take pictures of the covers of books. I was 1-clicking new reads to my Kindle right there in the store!

I came away from my first Amazon bookstore with a book in a bag and five other books downloaded to my Kindle. I also walked out onto 34th street with a smile on my face. This bookstore was nothing short of a revelation. I understand where Amazon is going with this, and it isn’t just a shipping hub, or an advertising play, or an electronics showcase. Those are ancillary benefits. What this is is simply a company that sells more books than anyone else who saw — even better than I did — how to sell more of them. How to please even more readers.

Now, when I pull into New York harbor on Wayfinder in a couple of years, I won’t need to open my own bookstore. I’ll just come fill out an application at this one. Or maybe at the shop in downtown Brooklyn that I hope they’ve opened by then.

The post If You Like Bookstores… appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

September 2, 2017

What a Book is Worth

There is something otherworldly about a book, something absolutely magical. This one simple container is somehow full of unlimited potential — you never know what awaits inside. What will you learn? What world will you be transported into? Whose life will you inhabit?

Nonfiction books teach us new facts, but the real magic is fiction. Here, we zip another’s skin over our own bones and suddenly see through their eyes, learn what it feels like to be someone other than ourselves. Fiction imparts the gift of empathy. It’s also a vehicle for satire, for warnings, for reflection, and most importantly . . . for hope.

An obsession for books binds millions of us together, all the avid readers and book collectors. In antique stores, we’re the ones ignoring the furniture and trinkets as we rummage through piles of musty tomes. We’re the ones at dinner parties standing in front of shelves and running our fingers across a stranger’s spines. We steal glances at jackets on subways. Used bookstores are mandatory stop signs. Piles of books stand like teetering monuments in our homes and on our bedside tables. Floor joists creak, bookshelves groan, and we sigh in contentment to be surrounded by all these stories and bound words.

My dream job was to work in a bookstore, something I was able to do in college and again while trying to make it as a writer. I couldn’t believe I got paid to open boxes of brand new books fresh off the press. I got to arrange them prettily on shelves. I also had the pleasure of working as a book critic, which lead to publishers sending me an unrelenting stream of advanced copies right to my door. Books newer than new! Not even out yet. I read and reviewed a book a day and still couldn’t keep up. The teetering monuments around my home grew taller, and I covered every wall of my house with bookshelves.

At some point, it becomes a fetish. The heft and feel of an old leather-bound book sends chills through me. I remember when Barnes & Noble came out with faux leather-bound books of old classics for $19.95, and I wanted them all. Poe, Swift, Shakespeare, Twain. I would gladly pay a premium for books I’d already read, just because they were more booky than other books.

I won’t admit to having a problem, because I don’t see it as a problem. Books have defined and shaped my life. I always had one in my hand as a kid, and these days I pick out my clothes based on my reading habit. When I try on a pair of cargo shorts, the first thing I do is make sure my Kindle slips easily into the lower right pocket. That’s my holster; there’s an entire library locked and loaded.

Transitioning to ebooks was not easy for me, I’ll admit. I resisted. But the advantages eventually won me over. My Kindle allows me to read more books, more often, and more affordably. I started traveling for work, and now I could take plenty of books with me and also buy more from anywhere in the world. Living on a boat, this portable library is crucial. It also means a lot of thought and care goes into which physical books I keep. Most of my reading takes place on my Kindle, but that doesn’t mean I’ll ever stop loving books. If anything, my appreciation has grown.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the years thinking about books and the book trade. As a reader, a bookseller, a writer, a publisher, an editor, and as a book designer. I ask myself questions about the value of books, the value of reading, the cost of publishing, and sometimes these questions lead me to weird answers. I’ve blogged about much of this over the years, and I’ve shared my strange ideas about books and bookselling as I describe my ideal bookstore or what I think publishers should do to reverse their falling fortunes.

My quest to understand the value of a book and reading has led me down many different and unusual paths. When it comes to my own work, I’ve long embraced piracy. I don’t see piracy as any different than a friend borrowing a book from a friend, or a single book making its way through a household or a school classroom. To me, the value is in being read. The danger is in losing an audience. I do not speak for other authors or condone stealing in general; I’ve just never had a problem with it when it comes to my own works.

I also think books are both priceless and that they should be free if possible. I love the Gutenberg Project, where you can download out-of-copyright classics at no cost. This website and an old ereader means a lifetime of reading and learning without spending another penny. My bestselling work of all time – the story that allowed me to become a full-time writer – has been free for years. You can get it here for nothing.

But I also believe in supporting writers and paying what you can for a good book. When authors try to give me their books for free, I usually decline and buy a copy for my Kindle. I’ve paid more than cover price for an early edition, or a signed copy, or an especially beautiful binding. I guess I think books should be readily accessible to all, and those who can afford to be patrons should support the medium and the artists. And this is precisely the world I believe we’re heading towards.

Small bookstores with full-price books are rebounding, largely because affluent readers understand the value of these bookstores in their communities, and they are choosing to pay extra to keep them open. Amazon, meanwhile, is doing gangbusters with their discounted print book sales, ebooks, and Kindle Unlimited, because not everyone can afford current retail book prices, and not everyone lives close to a bookstore. Different needs and different means for different readers.

If you haven’t heard of Kindle Unlimited, it’s basically an all-you-can-read book binging buffet. $9.99 a month to access a metric ton of ebook electrons. Programs like this place a very high value on reading by making more reading affordable to more people. And here is where the bizarreness of my philosophy on books arises: A high value for reading means a low price for books. A high value for books means the opposite.

Here’s a Venn Diagram for avid readers and book nuts:

On the right side, you have people who decorate their house with books they’ll never read (There’s actually a company that sells books by the linear foot for decorating your home. They arrive in all kinds of foreign languages. Beautiful and unreadable). On the left side, you’ve got people who will gladly mainline books into their neck veins once Amazon perfects the technique; these are the readers who are causing ebook and audiobook sales to explode while print sales stagnate.

And in the middle, you have addicts of both. Here is where I think we’re missing some potential in the book trade.

The publishing market is bifurcating between those who are obsessed with reading and those who are obsessed with books. While there is common ground between the two sides, important differences remain. I know people who read several books a week, year after year. They can’t afford to buy full-priced books to support this habit. Libraries, used bookstores, ebooks, free books, Amazon discounts, and programs like Kindle Unlimited are what they need. If you look at this bolded list, you’ll see all the things publishers regularly complain about. And yet these are the readers publishers need the most. Again, these readers can’t afford their habits any other way.

The right side of the Venn Diagram also thinks of reading as a defining characteristic of their lives, and quite rightly. Reading a book is an enormous investment in time. These people might read a dozen books a year, or twenty books a year. Spending full price at the local bookstore, and working through a chapter a night, these readers attach a lot of significance to reading and to books. They have home libraries. They’ve even read half of what’s on their shelves. They can’t resist a bookstore and always find something new to purchase. They just wish they had more time to read. They aspire to be like the first group, but life gets in the way. Publishers absolutely adore these readers and their value systems, even as these readers constitute a dwindling percentage of publishers’ profits.

The difference between these two crowds explains some conflicting headlines. You may have seen that most people still read physical books. You may have also seen that most books sold today are ebooks. These two facts are neatly explained by the fact that ebook readers consume far more books per person. It doesn’t matter how many people prefer physical books if they’re only buying a handful of them a year. A handful of books is a slow week for the group on the left side of the diagram. And ignorance of the existence of this group explains much of the ignorance and confusion within the book biz.

But what about the group at the intersection of these two groups? That middle slice of the Book and Reading Venn Diagram? Here is where you find the people who are both obsessed with reading and obsessed with books as objects. Here is much of the YA crowd and young readers in general, where solid objects provide highly prized substance for the expression of their individual selves. Here is where people who love one book in particular seek out signed copies, old copies, and multiple copies. This is a crowd that ebooks can’t sate. For this group, current print book standards are falling short. In the pursuit of profit margins, the margins within actual books are suffering. Fonts are shrinking, whitespace disappearing, paper and bindings getting cheaper, some formats disappearing altogether. Choices in print books are diminishing.

It need not be so.

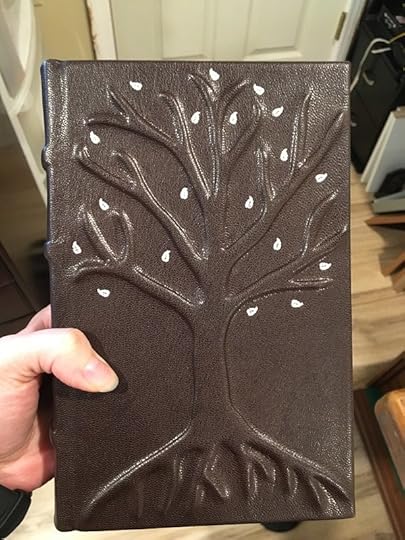

Always one to experiment, I decided to take these ruminations and questions and put them to the test. I started asking myself what I would pay for my favorite books, the ones that truly shaped me. Years ago, Barnes & Noble showed me that I would gladly pay $19.95 for a fake leather-bound copy of a book that I could otherwise legally download and read for free. That’s amazing when you think about it. It speaks to the value of the book as an object. The reading aspect costs nothing. The $19.95 is all about the packaging. How far can we take this?

[image error] There’s a Harry Potter hardback box set that comes in a special chest and sells for around $130. This doesn’t seem unreasonable at all to fans of the series. For some of my readers, hundreds of dollars for a first edition of WOOL seems reasonable to them, even though the ebook is free. This got me thinking about print-on-demand technology not as a route to cheap and quick, but as a route to one-off and exquisite. A technology that publishers have avoided and frowned upon is one that they could instead use to cater to that overlap in our Venn Diagram.

There’s a Harry Potter hardback box set that comes in a special chest and sells for around $130. This doesn’t seem unreasonable at all to fans of the series. For some of my readers, hundreds of dollars for a first edition of WOOL seems reasonable to them, even though the ebook is free. This got me thinking about print-on-demand technology not as a route to cheap and quick, but as a route to one-off and exquisite. A technology that publishers have avoided and frowned upon is one that they could instead use to cater to that overlap in our Venn Diagram.

Print-on-Demand (POD) means unlimited or zero copies, and both ends of this spectrum are important. Unlimited means never running out as demand goes up. Zero means not wasting a penny if there is no demand at all. POD is an end to guessing what readers want and constantly getting those guesses wrong.

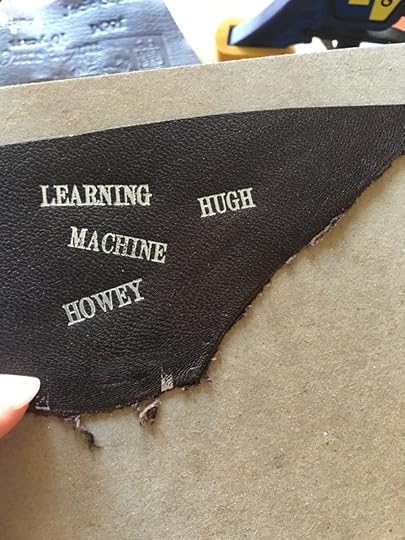

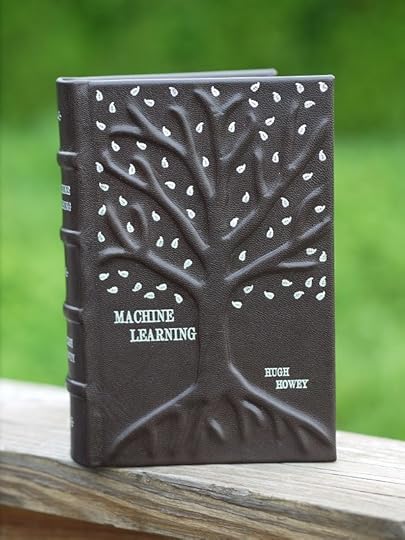

Check out this Print-on-Demand book:

That’s a copy of MACHINE LEARNING, a complete collection of my short stories. It will be released on October 3rd by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in hardback, paperback, and ebook. It was edited by John Joseph Adams, who also came up with the idea of publishing it. Before now, my short fiction has been scattered to the wind, published in so many places that I doubt anyone other than my mom has read them all. Some of these stories used to exist only on my old website; they became unavailable when I redesigned my homepage. Two of the included stories are brand new for this collection.

In addition to the stories, I wrote new thoughts about what each story means to me, or what I was thinking about or going through when I wrote them. These tidbits follow each story, and I think they add something to the reading experience. For those who are familiar with my work, you know how much the short fiction medium means to me. My success as a writer has mostly come through my short stories. I doubt any novel over my career will ever be as meaningful to me as this collection.

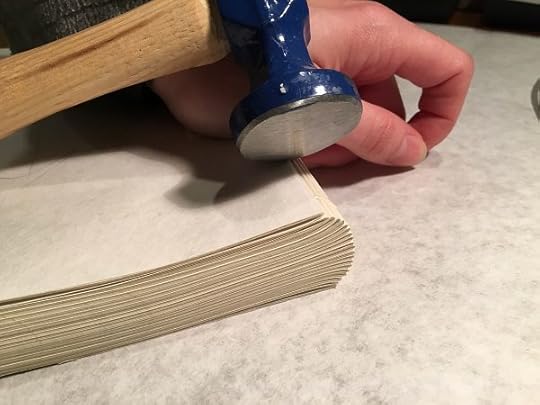

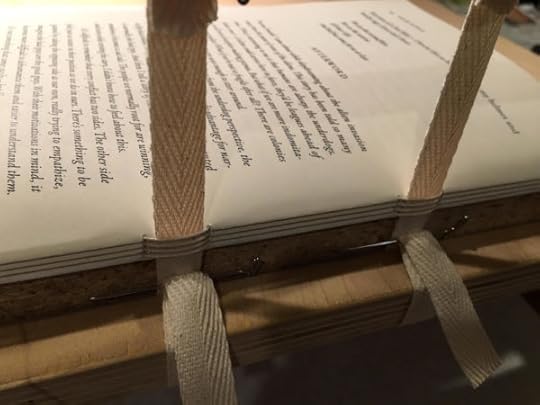

Which is why, when I needed to print out a proof copy of the manuscript to look over the final draft for changes and typos, I decided to do something a little different. Instead of going to Kinko’s and binding this as cheaply as possible (my normal practice), this time I went all-out. I tried to marry my love of the contents with an exterior to match. And here’s what I learned from this project:

I learned that I would have paid a week’s wage for a book like this, if it was the right book. As a bookseller, I used to make $10 an hour, and I worked thirty hours a week. Yeah, I was poor. But I spent what money I had on books, and I would’ve paid an entire week’s wage for a copy of ENDER’S GAME that looked like this – a one-of-a-kind hand-bound leather edition of my favorite read, signed by the author if possible. And I would’ve treasured that book for life and passed it down to a loved one. I’m one of those book freaks. I don’t think I’m alone. And I think it would cost precisely zero dollars for publishers to target this demographic using print-on-demand technology and by employing the fine folks who are keeping the art of bookbinding alive.

Here’s how I would make it work: I would convince a publisher (or a number of them) to enroll a ton of books into this program. I would especially go after the books that have sold millions of copies and have meant so much to so many readers. But really, just make every book available. It costs nothing, and millions of books are someone’s absolute favorite of all time. I bet every self-published author would add their works to the mix, and I bet Amazon would include their imprints as well.

The next thing you do is sign up a handful of book binders and crafters to meet whatever demand arises. I think you could get the cost of these books down if the people making them had steady sales. The crafter I used was Lindsey of BooksForAllTime. Lindsey is a true artist, and working with her was an absolute joy. I got to pick out the leather, the type of paper, the design on the cover, the gold leaf inlay, all of it.

So the program would work like it does with BooksForAllTime: You pick out your favorite book, customize it to your delight, and it shows up on your doorstep a month or two later. Slow. Expensive. The opposite of ebooks. But tapping into the same market of avid readers. That overlap in our diagram.

You might only own a dozen of these sorts of books in a lifetime. Or perhaps just one. Maybe you make a wishlist of your favorite books and make that list public for friends and family, so they know what to get you for Christmas or your birthday. Perhaps you have book clubs and programs that send you books on your wishlist every three months. Whatever you can afford. Maybe authors order one of each of their releases to have a library of their own books on display in their homes.

These books might cost $200 to $400 bucks apiece. Crazy? Then you aren’t part of the crowd I’m thinking of. I’m thinking of the crowd that collects these slowly, saving up, to see a row of Harry Potter books on a shelf that look like they came from Hogwarts itself. A Tolkien trilogy that even an orc could love. A Foundation Saga that could last from one foundation to another. The ultimate copy of Dune, Cosmos, or To Kill a Mockingbird. Eventually, after decades of a reading and collecting life, a small bookshelf of absolute treasures emerges. If you’re smiling at this imagery, then you are the crowd I’m thinking of.

But here’s where it gets very interesting: What if the author agrees to take a very small slice of that sale, a slice that would still be double the amount they make for a hardback (say, $3.00). And what if the publisher agrees to take the same measly cut (this would be a first). And what if the retailer did the same?

In other words: What if the book binder kept most of the profit?

Why would this make sense? Because I think there would be enough demand for these books to employ a good number of book binders like Lindsey. I think keeping the price of these books as reasonable as possible would expand the number of people who fit into the middle of the Venn Diagram. These exquisite books will expand the love of reading, the fetish for books and stories, and they’ll last for ages.

The ridiculous and ultimate fantasy is that we parlay the untapped money in the pockets of book lovers worldwide, and we move that money into the pockets of people whose jobs are being displaced or upended by changes elsewhere in the global economy. Books being bound in developing countries. Books being bound by former coal miners. Would global demand for bespoke books be enough to move a million leatherbound titles a year? If so, that’s a living wage for thousands of people. Much more if you’re talking about developing countries.

This might sound crazy, but community bookstores are made possible in part by the willingness of some readers and gift shoppers to pay extra for something they love. The reason books make such great gifts is that we feel like we’re buying something that is good for the recipient, as well as bringing them joy. Parents of book-loving kids know what this feels like: it’s like having kids who beg for their veggies.

Imagine buying a loved one a book they’ll cherish forever, and knowing that the person making the book is having their life changed as well. Imagine spreading the joy of reading and the joy of books by using a technology that removes the risk from publishing, that allows us to create something not cheap and expendable, but rather exquisite and irreplaceable.

This won’t be for everyone. Just the nuts in the middle.

So what would your favorite book be worth to you?

Anyone who’s interested in their own custom book, give Lindsey a shout. She’s amazing to work with. If you do want one of my books printed with her, and I own the rights, I’ll provide the PDF to her free of charge. All the proceeds will go to Lindsey.

Below are some pictures Lindsey sent me of my book in progress. Lindsey does this full-time and supports herself with her art. I am admittedly an old romantic and a dreamer, and one of those dreams entails hundreds of Lindseys out there making books that last for lifetimes, bringing joy to readers, spreading the love of books and literature, and supporting an artform that flourishes rather than fades.

Thank you for my book, Lindsey!

The post What a Book is Worth appeared first on The Wayfinder - Hugh C. Howey.

August 24, 2017

Writing Insights Part Three: The Revision Process

Welcome to the third entry in my four-part series on writing insights. In the first part of this series, I listed the things I wish I’d known before aspiring to become a writer. The second entry was all about how to get through the rough draft. Now I’d like to discuss how to improve your rough draft to get it ready for publication.

Many of the points in this section deal with the craft of writing. You may wonder why these are brought up after a rough draft is complete. Shouldn’t you learn to write before you begin writing? I wish it worked this way, but it doesn’t. You learn by doing, not reading about doing. Rough drafts require skills beyond the skill of writing. They are about endurance and stamina. They require willpower and force of habit. Many phenomenal writers can’t complete a rough draft and never will. This is why much of the writing advice out there is really just motivational advice to get you through that first draft. More “You can do it!” rather than “How-to.”

This is exactly as it should be. Once you know you can write a novel, you can learn through the revision process how to write a better novel.

Having said that, all of these insights are meant to be read at any time. If you haven’t written your first word, I would recommend reading this entire series before you begin. There are insights about the publication process in the next section that may influence how you structure your rough draft. And if you’re working on your tenth novel, there may be something in here that helps you see the writing process in a new light. Or you may see what’s missing from this advice and share your thoughts, which will help me and others in our writing processes. With this series, I mostly have in mind the aspirational writer, someone who is where I was ten years ago. So it assumes nothing and attempts to help anyone starting from scratch.

Before we get to the revision insights, I want to start by congratulating those of you who find yourself at this point of the writing process. It’s an amazing accomplishment. I’ll never forget the day I finished my first rough draft. I happened to be visiting my mother and sister at the time, and that night we went out for a celebratory dinner. A USB thumb drive containing a backup of my work sat on the restaurant table as we ate. I didn’t want to let that manuscript out of my sight! I still didn’t believe it. For the next week, I had to stop myself from telling perfect strangers that I’d written a novel. I also realized during this week that I had no idea what to do next. I’d worked so long and so hard to get to this point that I’d never researched the rest.

Here are the ten things I wish I’d known, sitting at that dinner table all those years ago…

Insight #21: Don’t rush to publication.

For many writers, getting the rough draft complete is the hardest part of writing a novel. It can feel like you’re done at this point, and you might want to get the project out into the wild so you can start on something new, or so you can get some feedback, or see if it’ll be the runaway bestseller that you hope it might. These impulses lead to tragic mistakes. New authors will often submit a manuscript to agents before it’s ready; or they’ll self-publish before the work is truly done.

Now is not the time to waste all the effort you’ve put into your rough draft. Now comes the fun part. The next step(s) will involve perhaps a dozen full passes through the work. Yeah, a dozen or more! Each pass will gradually smooth away rough spots and errors. It’s like taking a roughhewn hunk of lumber and turning it into a polished piece of furniture. You’ll start with heavy grit sandpaper and work your way down to wet-sanding a typo here or there.

The beauty of the revision process is that this is where you’ll learn to become a great writer, much more so than in the rough draft stage. The techniques you pick up as you shore up your story and polish your prose will carry over into the next rough draft. Because of this, the writing process will get easier and easier. The revision process will become faster and faster.

I’ve heard some writers suggest that you should step away from a rough draft for a length of time, but I never understood the usefulness of this. When I finish a rough draft, I celebrate for a day and then go right back to the beginning of the novel to start the revisions. There are a handful of main things I want to accomplish with the first pass: (1) I want to plug any missing sections (scenes or chapters I skipped). (2) I want to make the prose more readable and improve the flow between sections and chapters. (3) I want to give the characters and my world more depth and detail. (4) I want to tighten the plot, add some foreshadowing, close any logical holes.

Now is also the time to think about how you plan to publish this work, which is the area we’ll cover in the fourth and final part of this series. If your rough draft is a 300,000 word epic fantasy tome, and you want to publish this with a major publishing house, your revision process is going to involve cutting that draft up into three novels to create a trilogy. This will require some plot restructuring. One of my keenest insights that I possess now, which I didn’t appreciate when I started writing, is that how you publish will influence what and how you write.

In the next section, we’ll also discuss how insanely easy it is to publish these days, and this is why some patience is required. In the old days, you didn’t have a choice but to be patient. It could easily take several years (if at all) to bring your book to market. Now it takes a few hours. I want to convince you to take longer. At least ten revision passes before you submit to agents or self-publish. I promise you’ll be glad you took this advice.

Insight #22: It is often easier to rewrite from scratch than it is to revise.

Before we discuss revising, it’s worth pointing out the alternative: rewriting. Yes, I hear your collective groans. We just got done writing the rough draft, and now we have to start a scene or chapter from scratch?! From a blank page?! Can’t we just move a few words or sentences around and be done with it?

Usually, you can. The revision process mostly involves massaging what’s already in place. But there are times when revising actually takes a lot longer than a rewrite. Understanding when this makes sense, and being brave enough to tackle these challenging moments, is often the difference between success and failure. I’ve seen entire manuscripts abandoned and/or destroyed because of this fatal oversight.

This is especially true with the opening chapters of a manuscript, which are the most important chapters for hooking your audience, whether that audience is an agent, a reader, or a publisher. As you wrap up your rough draft and go back to the beginning, now is the time to explore rewriting as well as revising. You know your story and your characters more fully now. Your writing skills have improved through the hours and hours you’ve invested in this project. Maybe your opening feels a little stale. Or you wonder if the story shouldn’t start with a different scene or a different piece of information. You can try revising, or you can open a blank document and see what kind of opening chapter you would write now. It’s a fun exercise. You might surprise yourself.

This technique works wonders, and it works throughout your novel. You can peel off any scene or chapter or sentence and try it again from scratch. There have been times when I’ll spend hours trying to get a chapter or paragraph just right, then pound out something new in a fraction of the time that’s far cleaner and better. Our existing words often get in the way. Learn to step around them and try something new.

This fits well with the last insight from the previous entry in this series, about writing lean. The beauty of writing lean is that you spend more time adding material, and less time wrestling with the pain of deletion or the discomfort of massaging the wrong words into a different order that isn’t much better.

Insight #23: Great books are all about pacing

To become a better writer, it helps to understand how the delivery of words affects a reader’s mood and their retention of information. The most important tool in this regard is pacing. Pacing can mean different things in different contexts. The next few insights are all about pacing in one way or another.

Let’s start with the importance of overall book pacing and construction. It can help to consider extreme scenarios in order to arrive at more general truths. For instance, imagine a 300 page novel with no chapters or scene breaks. I’m sure they’ve been written or considered by people eager to break rules and convention. I imagine they are nearly impossible to read. Why? Because our brains are built to absorb ideas in chunks and to process those chunks individually.

We experience things in the moment, move those experiences into short term memory, and then perhaps to long term memory. If we get too much information all at once, we can’t process it well (or at all). Chapters and paragraphs signal an opportunity to file away what we just absorbed and prepare to absorb another chunk. This is why paragraph length is critical for flow and retention. If possible, paragraphs should be of similar length, each one containing three to seven sentences. This can vary depending on how long or short the sentences are (more on that in a bit). And this rule can be broken to great effect. Those effects are diminished when the rule is ignored altogether.

Short paragraphs stand out – but only if used sparingly!

And long paragraphs have their place in our stories, especially if the desired effect is to ease the readers brain into a somnolent state, like the sing-song of a lullaby. Proust was a master of paragraphs like these; they went on for pages, and were full of sentences that stretched line after line, full of clauses and lists, huddled together between commas and semi-colons and dashes, all with the combined effect not of conveying concrete information and facts, but to get the reader in a certain mood, perhaps to make them wistful, to deprogram their concrete minds so they were ready for the dream-state of Proust’s expert meanderings; in this, the words become like music, more notes than ideas, and the reader’s muscles themselves relax, a hypnotic trance ensuing, perhaps at the risk of losing them to literature’s great nighttime enemy and thief: sleep.

Practice both types of paragraph structure and pacing. Look for examples in your own reading. Ask how the authors you admire are affecting your mood as you read their prose, and then ask the same questions as you revise your rough draft. Chop up that long paragraph into two or more. Be frugal with your short declarations so you don’t rob them of their power. Treat your words like lyrics and listen for the song they sing.

Insight #24: Find your cadence between action and reflection

The pacing in the previous insight deals with how words are lumped together. Their physical structure, if you will. There’s a second kind of pacing, and this one deals with the actual content and type of words used. It’s the flow between action and reflection, and it’s especially crucial for works of fiction.

Action scenes don’t necessarily mean gunfights and car chases and alien invasions. An action scene can be an argument between two lovers. It can be a fierce internal struggle as a character decides to leap or step back from a metaphorical ledge. Action scenes are anytime something major is happening in the plot or to the characters. The reader is usually flying through these passages at a higher rate of speed, eager to see what happens next. Most often, these scenes have large blocks of text and less dialog, but that’s not always the case.

Reflection is what happens after the action. It’s when characters absorb the change that’s happened and plan what comes next. Period of reflection also give the reader a chance to absorb what’s happened and to guess or dread what might happen next. This is the cadence of your book, the rise and fall of action and reflection.

Now, if an entire novel was written with nothing but action, it would make for an exhausting read. And if a book consisted of nothing but constant reflection, it would be difficult to wade through. In the former, you would have change in your plot but not your characters. In the latter, you would have change in your characters but no plot. Every book should contain some balance between the two.

That doesn’t mean the same balance. A literary novel will typically have lots of reflection and very brief spurts of action. A genre novel will have lots of action and shorter pauses for reflection. I haven’t seen a definition of what makes a work “literary” that I fully buy, but maybe this fingerprint of cadence comes closest. It could be why many genre fans can’t read literary novels, and why many literary fans can’t abide genre works. It doesn’t matter if the genre works are as well-written as the literature – there’s simply too much happening. Not enough reflection. I would argue that pace defines these books far more than content. Which is why some great works of science fiction, like THE LEFT HAND OF DARKNESS or THE HANDMAID’S TALE, read more like literary novels (and are often shelved as such).

As you revise your work, look for places where the action goes on too long and consider inserting a pause for reflection. Let the characters catch their breath in an elevator, crack a joke or two, or tend to some wound or primal fear before you pick up the pace again. Similarly, look for anywhere that characters are ruminating too long and figure out how to spice things up. If you’re bored with what you’re writing, chances are a lot of readers will be bored as well. Make a gun go off; a car backfire; someone in the neighboring booth get the wrong order and pitch a fit; a zombie pop up that has to be dealt with, anything. And if you feel like you’ve gone on long enough, there’s always the em dash and a sudden exit—

Insight #25: Don’t repeat yourself. Unless it’s deliberate. And then repeat yourself carefully.

Alliteration and repetition are both an important part of pacing, and they both highlight the importance of grasping reading psychology. Readers love repetition when it is deliberate, for extra punch, for added stress. But our minds trip over accidental repetition, as when the same words appear too near to one another in a paragraph or chapter accidentally.

The psychology of this is strange, and it varies slightly from reader to reader. Common words can appear throughout the same sentence or paragraph without tripping the reader up. Uncommon words draw attention to themselves. If the reader sees a rare word twice, part of their brain will perk up and draw attention to the second sighting, which breaks the flow and distracts them from the content or emotional impact of the sentence. One of the most common things you’ll see from a good editor is similar or same words highlighted if they’re too close to one another in a manuscript. The editor will suggest changing or deleting one of them. This is always sound advice.

Repetition, however, can be extremely powerful if wielded appropriately. Play around and experiment. Pay close attention as a reader to see when you trip up and how you might have avoided that mistake in your own writing.

Insight #26: Reading is aural

I find it fascinating that we can hear ourselves think. When I was very young, I had a hard time telling if this was indeed the case. When I read silently to myself, am I “hearing” those words in my mind? Or am I just thinking them? What seemed to settle the question for me was the ability to hear various accents in my head. I could think with a British accent, or a French accent, which meant the words didn’t just have meaning, they had pitch and inflection and all the properties of sound.

This is why cadence is so important when it comes to writing. It’s why the long paragraphs mentioned (and demonstrated) above have a powerful effect on us. This is also how we can hear our characters’ voices, and why it’s important to make those voices distinct. Common writing advice includes the importance of observation: sit and watch crowds and make note of how they move, how they dress, how their features look. This is great advice. But we have to observe with our ears as well.