Richard Denning's Blog, page 8

February 9, 2013

Burial in Anglo-Saxon England

When the Anglo-Saxons first came to England in the 5th century they were pagan. They believed in a pantheon of gods including Woden( Odin), Thunor (Thor) and others. By the 8th century pretty much all of them had converted to Christianity. The beliefs of both religions was that there was an afterlife but how they saw that afterlife was very different and that was reflected by the burial customs. As a result it is generally quite possible to tell the difference between a Christian and a Pagan grave and that difference helps to track the spread of Christianity across England.

Pagan Afterlife

The old religions of the North Germanic and Norse peoples believed that there was an afterlife. Or rather several afterlives. Half of the warriors who died in battle would go to Woden/Odin’s hall in Valhalla. During the day they would fight battles and at night feast in Woden’s halls. The other half were taken by the goddess Freyja to the Folkvangr – her afterlife paradise.

So much for folk who died in battle. What about those men who did not? What about Women or children? Well here are several possibilities. Some Norse legends speak of a Holy Mountain – a blessed realm rather like a Christian heaven vaguely in this world and vaguely in the next. Others talk of Hel.

Now Hel, (spelt with one L) is the goddess of the dead. Her realm may have once have been the destination of those who did not die in battle. As the years go by – and MAYBE as a result of contact with Christianity – it becomes a dark dreary place and eventually a place of punishment.

Pagan Burial

What is clear is that in all cases activities similar to that of life before death would go on. Men would would fight or build or make things. Women would sew and cook etc. Therefore you needed weapons and day to day items. As a result Pagan Anglo-Saxons were buried WITH goods. Warriors would be buried with their weapons, armour and shield. Crafts-men like blacksmith might be buried with their tools. Everyone would have a small knife – a seax perhaps and probably strike-a-lights and fire making tools. Women might have sewing equipment, spindles and perhaps the keys they used to lock the food up in life.

There is a mixture of approaches to the question of cremating or burying the dead. It seems from the graves found that the Saxons of the South favoured Burial more than the Angles further north but in all locations there is a mixture of approaches. What seems to be the case is that if a person was burnt then the grave goods were burnt too (from fragments of objects found in urns) . The urns were then buried in cemeteries.

Ship Burials

A few special, famous or rich individuals were granted a much more dramatic send off. Some were buried inside a ship which itself was buried in the ground. One of the most famous examples of this was the Sutton Hoo Burial in East Anglia. Just before World War Two a series of mounds were excavated and one was found to contain the burial of a king – thought to be the powerful King Redwald of East Anglia who died in the 620′s. His grave contained a glittering array of treasures including his amazing helmet which is kept at the British museum.

Christian Burials

With the coming of Christianity another view of life after death was introduced. Man and Women would be reborn into a world free from strife and pain and in the presence of God. There would be no need to fight or cook or sew. As such there was no need to prepare people for their heavenly reward by burying them with objects. Indeed to do so was often seen as a pagan tradition. As a result they were buried in simple clothes and with almost no adornments. There was the odd exception as revealed by a recently discovered burial. Near Cambridge in the mid 7th century – only fifty years after the Augustine mission brought Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons- a 16 year old noble women was buried. Only one object was found in the grave – a golden cross which she wore on her chest.

I write novels set in Early Anglo-Saxon England during a time where the Saxons were clashing with the Welsh and Pagan religions fighting Christianity. Read more in the Northern Crown Series

February 2, 2013

A winter visit to the Black Country Museum

It was a bright, dry but cold day today. It was my wife Jane’s birthday (on Monday actually) and she fancied a trip somewhere with just us 4 going along. We realised it had been years since we had been to the Black Country Living Museum and off we went.

What this museum did was to to collect buildings from all over the black country – often ones scheduled for demolition or boarded up and move them brick by brick to the site and then rebuild them so that they feel like a real village. Then they fill the village with staff that know all about the buildings and bring them to life. So the chip shop really cooks Fish and chips and what wonderful chips they are – done in terribly unhealthy beef dripping that make them taste superb. Many houses will have fires and ranges lit and “housewifes” ready to explain what life was like eighty or a hundred years ago.

We saw a chain being made in the foundry, bread being baked in the bakery bread oven and bought old fashioned sweets from the sweet shop. The school has a strict teacher i ready to shout at you if you do wrong!

You can go down the coal mine and see how terrible conditions were. We also went on a boat through the tunnels where they mined limescale and we also watched a silent movie in the cinema.

I think my favourite building is the pharmacy – it always sparks professional interest. I let my eyes wander across the jars and see how many are familiar to a GP today and how many obscure and unknown.

Well worth the visit – and a ticket allows unlimited return trips in a year.

January 30, 2013

Two executions – but one man was already dead

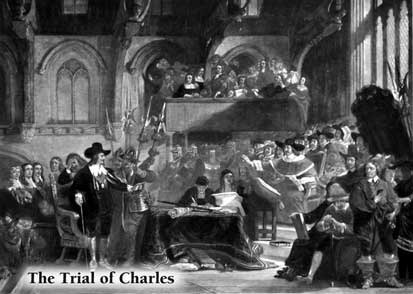

On the 30th of January 1649 King Charles I of England was beheaded - the first and only English monarch to be executed for treason.

The execution occurred at the end of a trial which itself was controversial. England had NO law that allowed a king to stand trial and indeed the court had to write its own rules based on Roman law. The trial was not popular – of 135 Judges that were summoned only 68 turned up and NONE of them wanted to preside. The charges laid against the king were that he acted:

“Out of a wicked design to erect and uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people of England.”

The King did not recognize the court and refused to defend himself. In the end the court passed judgement.

“He, the said Charles Stuart, as a tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy to the good of this nation, shall be put to death by severing of his head from his body.”

The execution occurred on 30th January. Charles was allowed to go for a last walk in St James’s park and then ate a final meal of bread and wine. The original exceutioners refused to undertake the act but in the end two anonymous men were paid £100 and were allowed to wear masks. At 2.00 o’clock, the king was led to the scaffold. It was a cold day and he asked to wear thick underclothes as he was worried that if he shivered in the cold, the crowd might think that he was scared. Charles gave a last speech but very few people cold hear his words. He was then beheaded.

A loud groan went up from the crowd when he was killed and there was a terrible fear that the nation was drawing the wrath of God upon them. However, this did not stop many in the crowd paying to dip cloth rags in the blood of the dead man – a feeling that the blood of a king being powerful still prevailing. Soon afterwards the Commonwealth abolished the position of king.

The execution of Oliver Cromwell

Now we wind forward 12 years to 1661. Charles II has returned and with the restoration of the monarchy there was a general amnesty on the opponents of Charles I as part of the agreement of Breda that allowed Charles II to come back. There was ONE major exception to the amnesty. Any man who had signed Charles I’s death warrant or been involved in the execution was a regicide. Charles II demanded that these men die.

Of the original men involved actually only 13 were executed. Others were imprisoned and many fled abroad to live out their lives in exile.

Four men had died before the restoration. These were dug up and ritually hung. The most famous of these was Oliver Cromwell himself who had been the architect of the defeat of Charles I and Lord Protector during the republic.

The day chosen for this act of revenge was the anniversary of the execution of Charles I – the 30th of January 1661. Cromwell’s body was exhumed from Westminster Abbey, and along with that of Robert Blake, John Bradshaw and Henry Ireton was hung in chains at Tyburn. Later his head was displayed on a pole outside Westminster Hall until 1685.

I could not resist referring to the head of Cromwell in The Last Seal

Westminster had its own shops and in Westminster Hall there was a market. The boys at his school would often go there and spend their pennies on books, sweets, trinkets and toys. Ben had been many times and even the decapitated head of Oliver Cromwell, mounted high up on its roof, did not interest him anymore. Although it had been a curiosity of morbid fascination when he had first arrived at the school, he had seen it so often that he barely glanced at it now. Ben had a more distant destination in mind in his search for something distracting.

http://www.richarddenning.co.uk/thelastseal.html

January 17, 2013

A Bolton, a Bolton! The White Hawk!

"A Bolton, a Bolton! The White Hawk! God for Lancaster and Saint George!"

England, 1459: the kingdom stands divided and on the brink of civil war. The factions of Lancaster and York vie for control of the King, while their armies stand poised, ready to tear each other to pieces.

The White Hawk follows the fortunes of a family of Lancastrian loyalists, the Boltons, as they attempt to survive and prosper in this world of brutal warfare and shifting alliances. Surrounded by enemies, their loyalties will be tested to the limit in a series of bloody battles and savage twists of fate.

This period, with its murderous dynastic feuding between the rival Houses of York and Lancaster, is perhaps the most fascinating of the entire medieval period inEngland. Having lost the Hundred Years War, the English nobility turned on each other in a bitter struggle for the crown, resulting in a spate of beheadings, battles, murders and Gangland-style politics that lasted some thirty years.

Apart from the savage doings of aristocrats, the wars affected people on the lower rungs of society. One minor gentry family in particular, the Pastons of Norfolk, suffered greatly in their attempts to survive and thrive in the feral environment of the late 15th century. They left an invaluable chronicle in their archive of family correspondence, the famous Paston Letters.

The letters provide us with a snapshot of the trials endured by middle-ranking families like the Pastons, and of the measures they took to defend their property from greedy neighbours. One such extract is a frantic plea from the matriarch of the clan, Margaret Paston, begging her son John to return fromLondon:

“I greet you well, letting you know that your brother and his fellowship stand in great jeopardy at Caister… Daubney and Berney are dead and others badly hurt, and gunpowder and arrows are lacking. The place is badly broken down by the guns of the other party, so that unless they have hasty help, they are likely to lose both their lives and the place, which will be the greatest rebuke to you that ever came to any gentleman. For every man in this country marvels greatly that you suffer them to be for so long in great jeopardy without help or other remedy…”

The Paston Letters, together with my general fascination for the era, were the inspiration for The White Hawk. Planned as a series of three novels, TWH will follow the fortunes of a fictional Staffordshire family, the Boltons, from the beginning to the very end of The Wars of the Roses. Unquenchably loyal to the House of Lancaster, their loyalty will have dire consequences for them as law and order breaks down and the kingdom slides into civil war. The ‘white hawk’ of the title is the sigil of the Boltons, and will fly over many a blood-stained battlefield.

In the following excerpt, the Lancastrian lord “Butcher” Clifford prepares to defend a river crossing against the Yorkist host:

“Lord Clifford sat his horse on the north bank of the River Aire and watched the glittering mass of the Yorkist vanguard march into view from the south.

It was a bitterly cold afternoon, with a hint of ice on the wind. Clifford took no notice. He was the lord of Skipton and Craven inYorkshire, and the atrocious weather and desolate landscape of the north appealed to his stark nature. This was his country.

“The Butcher”, the Yorkists had started to call him, for his cold-blooded killing of Edmund of Rutland after the Battle of Wakefield. Clifford gloried in the name. The more his enemies feared him, the better. He was a hard man, consumed by a lust for revenge since the death of his father at the First Battle of Saint Albans, six years previously.

Clifford had slaked his thirst for Yorkist blood somewhat onRutland, and still felt a tight little shiver of pleasure at the memory of his knife plunging into the boy’s soft white gullet. One death, however, wasn’t enough. Only the bloody annihilation of all the Yorkists inEnglandwould suffice.

“Fauconberg’s men are in the van, as we suspected,” said Lord Neville, his second-in-command, pointing at one of the enormous standards carried at the head of the Yorkist troops, displaying blue and white halves painted with Fauconberg’s distinctive sigil of a sable fish-hook in the top right corner.

Clifford said nothing. He had already repelled an attempt by the Earl of Warwick and Lord Fitzwalter to cross the stone bridge over the Aire, falling on the Yorkist camp at dawn and slaughtering many soldiers in their beds. More had died as they tried to escape across the river, drowned or swept away in the icy waters. Lord Fitzwalter had been mortally wounded, and Warwick himself barely escaped with an arrow in his thigh.

The bridge was the only reliable crossing over the flood-swollen Aire for miles in either direction. The Yorkists had to cross the river to engage the enormous Lancastrian army slowly deploying a mile to the north, between the villages of Towton and Saxton. Sooner or later, Clifford appreciated, they would realise how small the force was that opposed their crossing…”

If this whets your appetite, then please check out the paperback and Kindle versions of Book One below…

The White Hawk – paperback version

January 16, 2013

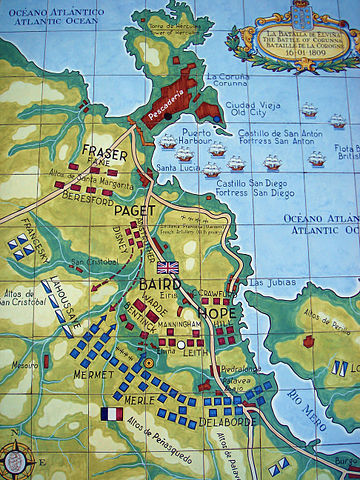

The Battle of Corunna Jan 16 1809

On this day in the year 1809 the British army under the command of Sir John Moore fought a critical battle outside the port of La Corunna in northwest Spain. Their victory at the battle allowed the escape of the ragged remains an expeditionary force that had been pursued across Spain by Napoleon’s armies.

Background

In the late summer of 1807 Napoleon was all powerful in Europe having smashed the Austrians, Russians and Prussians in successive campaigns beginning in 1805. Now no nation dared stand aginst him except ‘perfidious Albion’ – Britain. Napoleon forced all of Europe to close their ports to British trade. One nation refused. Britain’s oldest ally – Portugal would not comply. Napoleon sent an army through Spain (his ally) and into Portugal. Then he made a fatal error he deposed the Spanish king and put his own brother on the throne. All of Spain burst into rebellion. Britain sent an expeditionary force which defeated the French in Portugal whilst the Spanish destroyed a French army at Bailen and then forced the French back towards the border with France.

In 1808 Napoleon now took direct action. He marched into Spain with 200,000 veterans of Austerlitz and Freidland and soon smashed the Spainish armies. At this point in time in the autumn of 1809 Sir John Moore was in command of the British. Sir Arthur Wellesley (later Wellington) was back in Britain at the time. Moore led the British into Spain – advancing to Salamanca – in attempt to cut the French supply lines and help the Spanish. Napoleon now saw his chance to crush Britain’s professional but small field army. He swung northwards and soon Moore realized that he must flee or be destroyed.

A winter march

What happened next was one of the more extraordinary episodes of the Peninsular war. Setting out on Christmas day 1808 Moore covered 250 miles with his army of mainly foot soldiers over the next 18 days through the most appalling winter conditions of snow and ice and through the mountains of north west Spain. The British cavalry managed to keep the French from catching up so that on 11th January they arrived at the port of La Corunna only to find that the harbour was empty. The Royal Navy has not yet arrived.

The Battle

The British had no alternative but to fortify the port and wait for the ships and hope the French did not arrive. Unfortunately Marshall Soult one of Napoleon’s best generals turned up with his Corps on the 15th of January. The Navy was on its way but the British had to first turn and fight once more – to keep the French at bay until they could escape.

the sides were evenly

Marshall Soult came up with a simple battle plan. He would attack to pin the British left and center whilst one of his divisions under Mermet attempted to turn the British right at the village of Elvina. The attack on Elvina was a success and Mermet was soon attacking the heights beyond. Moore knew how important Elvina was so threw men that way and the possession of this village changed hands repeatedly with Moore having to commit his reserves to attempt to hold the French attack on his wing.

It was during one of these engagements that he was hit by a cannonball and fell fell mortally wounded. He would take hours to die but was described as brave and composed throughout. Soult had tried desperately to break through at Elvina but the British were just able to hold on as night came. Both sides lost around 1000 men in this battle. The following day the British were able to start embarking on the ships that had now arrived.

Moore’s action had saved the British army and would allow Sir Arthur Wellesley to continue the war and one day drive the French from Spain.

January 8, 2013

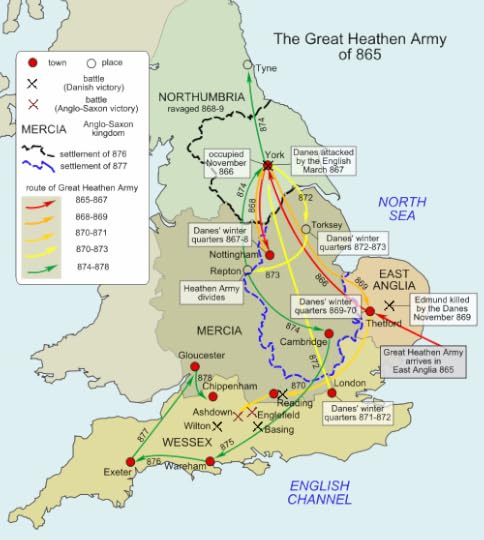

Battle of Ashdown Jan 8 AD871

Anglo Saxon Chronicle for 871

This year came the army to Reading in Wessex; and in the course of three nights after rode two earls up, who were met by Alderman Ethelwulf at Englefield; where he fought with them, and obtained the victory. There one of them was slain, whose name was Sidrac. About four nights after this, King Ethered and Alfred his brother led their main army to Reading, where they fought with the enemy; and there was much slaughter on either hand, Alderman Ethelwulf being among the slain; but the Danes kept possession of the field. And about four nights after this, King Ethered and Alfred his brother fought with all the army on Ashdown, and the Danes were overcome.

This day in the year 871 was the date of a early victory in the military career of the man who would one day be called Alfred the Great. The Battle of Ashdown, in Berkshire took place on 8 January 871. Alfred the Great, then merely a prince of 21 years age, led King Ethelred of Wessex’s army in a victorious battle against the invading Danes.

Build up to a battle:

In 870 the Danes were rampant. They had already swept through the Kingdom of Northumbria away then in 869 East Anglia fell. Now they sailed up the Thames and captured Reading. Advancing to Englefield they were halted and given a bloody nose by Aethelwulf, the Ealdorman of Berkshire. King Ethelred and Prince Alfred, arrived with their army and the Saxons were able to force the Danes back to Reading. At Reading however the tide of war turned once more in favour of the Danes. The Saxons were unable to break through the defenses of the city and they were was driven back across Whistley marshes and the Berkshire Downs. The Danes advanced out of the city looking to finish the Saxons.

Alfred Takes action

Prince Alfred now acted with considerable vigour in an attempt to rally his brother’s forces. On the downs is a hill called Blowingstone Hill. At its peak is an ancient sarsen stone – “Blowing Stone,” which he used to send out a rallying call across the downs. Then uniting the Saxons he and Ethelred marched out and prepared for battle on the plain of Ashdown. Bizarely at this precise moment, with the Vikings approaching, King Ethelred decided to go to church near by leaving Alfred in command.

Armies:

Saxons

Under Prince Alfred -1000 men.

Danes

Under Kings Bagsecg and Halfdan Ragnarsson

800 men.

approx. 800 men

These figures may not seem large when we think that Waterloo saw 210,000 men engaged BUT in the Dark Ages forces of this size decided the fates of nations.

Battle of Ashdown:

Initially neither army appeared eager to open the battle. The Danes had actually deployed on higher ground and so naturally did not want to leave it. Alfred realized that he must take the initiative and ordered the Saxon shield wall to advance. What followed a brutal battle of attrition with bloody casualties on both sides. King Bagsecg was killed as well as five earls. With their losses heavy teh Danes fled back to Reading.

The Outcome:

The chronicles report loses as being heavy on both sides, but while Ashdown was a triumph for Alfred, the victory was short lived as the Danes defeated the Saxons again at Basing and at Merton within a few weeks. At Merton, Ethelred was mortally wounded and Alfred became king. The following year after further defeats Alfred made peace with the Danes. For Alfred there would be many more battles and many more victories and defeats but Ashdown at least stalled the Danes advance through Wessex for a while and kept that kingdom alive.

I write novels set in early Anglo-Saxon England. Find out more here:

http://www.richarddenning.co.uk/theam...

January 5, 2013

12th Night Traditions

As I write this blog a very loud party is going on downstairs as my daughter has a 16th Birthday party. As the aged parents we are in exile upstairs. That said it is a traditional party night as it is 12th night: the 12th and last night of Christmas. 12th Night was traditionally celebrated on the night of the 5th of January – the night BEFORE the 12th day.

This may seem odd to modern minds as we are used to a day starting at Midnight and so night follows day. To the ancient peoples (and right through medieval times) the day ended at sunset. The night that then followed belonged to the following day. Thus the night AFTER Christmas eve was the first night and also coincided with the pagan saxon Mother’s night. That night started the 12 days just as 12th night heralded its end.

12th Night was a time for partying. There was no particular celebration associated with 31st December as in Saxon times that was not the last day of the year. For a long time a new year started on Mother’s night (the 1st night of Yuletide which later became the first night of Christmas. ) and later a New Year actually started around 25th March which was the Spring Equinox date. The New year beginning on 25th March lasted until the 18th century. So 31st December was not a big night. 12th Night was.

"Twelfth Night Merry-Making in Farmer Shakeshaft's Barn", from Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe, by Phiz

In Saxon times a popular tradition is the custom of wassailing. This word comes from the Old English was hael, meaning to your health. Everyone at a Twelfth Night celebration would drink from a large wassail bowl, followed by a toast or a wassail to their health.

Another custom is the lighting of fires with all those attending circling the fire drinking to each other’s health and fortune.

[image error]

An Anglo-Saxon tradition celebrated on Twelfth Night in which folk drunk from a great bowl and toasted each other’s health and good fortune

December 30, 2012

Sovereign by C.J. Sansom

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I have l...

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I have loved each of the Shardlake novels.

If you have not read any of these novels I will give you a brief outline. Shardlake starts out as a strong reformist working for Cromwell during the dissolution of the monasteries. In Dissolution he has to investigate a murder in a monastery. In Darkfire (the 2nd in the series) it is the pursuit of Greek Fire which once again brings him into the political stage.

This third novel follows on a year after the events of Dark Fire. Shardlake has to catch up with the 1541 King’s Progress to the North at York (the aim of which were to bring the North back into loyalty to the King after the revolts of recent years).

Sent on a secret mission by Cranmer, Shardlake soon gets embroiled in a new plot against Henry VIII when a workman is killed and he soon finds his life is in danger.

This story winds its self around the Progress, the King’s growing tyranny, the affairs of Catherine Howard and the corrupt goings on at court. Shardlake has already lost his zeal for religious reform and in this book comes to realise even more just what a monster Henry has become.

Sansom brings this world vibrantly to life with such delicious detail that you feel you are walking the street sof 16th century London and York. You too feel the fear the king brings and the horrors of torture and execution that were instruments of state and power.

I will be buying the next in the series very soon.

December 9, 2012

Stars and Constellations in Anglo Saxon and Norse Times

The Norse and Anglo saxons looked at the world in a way very different to the mythology that was developed by the Greeks and Romans. Most of the constellations in our night sky have derived their modern names from the Greek myths. Yet the ancestors of those of us from England and Scandinavia had totally different names for the shapes formed by the stars above us. The English kept only very scanty written records before they converted to Christianity and at the same time came into greater contact with the Roman Catholic world. That world changed dramatically many aspects of our culture and this applies to the stars as to other areas of life. Thus by the time the English are writing things down in Alfred the Great’s era, they had abandoned the former names and stories. The Norse- Viking world is different. Written documents survive in greater numbers and because the Norse peoples did not convert until much later (even as late as the 12th century) their names for stars and constellations survive. The English shared a common mythology so we can assume that these same names – or very similar is what the English also used.

The Origins of the Stars

The Edda was a book of Icelandic-Norwegian legends and in it there is a passage saying where the norse believed stars came from. Then they (the gods) took the sparks and burning embers that were flying about after they had been blown out of Muspellheimr, and placed them in the midst of the firmament both above and below to give light heaven and earth. They gave their stations to all the fires, some fixed in the sky, some moved in a wandering course beneath the sky, but they appointed them places and ordained their courses.

Muspellheimr is the one of the Norse worlds where fire spirits lived.

Names of constellations

Friggerock (Frigg’s distaff) – A distaff was part of spinning equipment and was seen as the three stars in Orion’s belt. What we see as a sword hanging from that belt was seen as the spindle. The goddess Frigga is often depicted with a spinning wheel.

Thiassi’s Eyes – this consists of two Gemini stars Castor and Pollux, that are side by side of equal brightness resembling two eyes, reaching their peak in the sky at midnight in January. Thiassi was the name of a frost giant and father of Skandi goddess of winter..

Dain – Dain was the name of one of the deer who lived in the World Tree. The bright star Vega is its eye, and the four Lyra stars form its antler.

Dvalin– Another of the deer constellations, Much of the constellation Cepheus make up the deer with the North Star its rear foot,.

Durathror Yet another deer made from much of the Perseus collection.

Ratatosk – the squirrel constellation. Formed from Cassiopeia.

Eagle – the eagle constellation is how the Norse saw Cygnus the Swan.

Nidhogg– This is the constellation of the serpent who lived and gnawed at the roots of the world tree Yggdrasill’s. The constellation we today call Scorpius, was Nidhogg.

The Wagon or Hellewagen was formed by the modern Great Bear/ Plough/ Big Dipper. It was seen as a wagon maybe carrying the dead and probably was seen as Woden’s wagon.

Loki’s Torch – This was the bright star Sirius

Planets

blóðstjarna - or bloody star was probably the norse name for Mars whilst Venus was called either morgunstjarna (morning star) or Friggjarstjarna Frigg’s star.

There is a lot of guess work about exactly which stars were called what but these fragments that survive give us a glimpse of people who did exactly what we do – look up and make pictures and shapes in the night sky

December 2, 2012

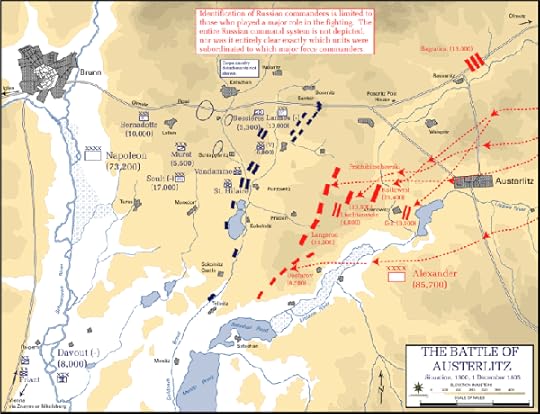

Dec 2nd 1805 Battle of Austerlitz

On this day in 1805 Napoleon won arguably his best battle and one that went a long way to convincing his enemies that he was invincible. It happened at Austerlitz.

In the summer of 1805 France was at war with the third Coalition between Britain, Austria and Russia. Whilst British eyes were on the seas and in particular concerned with Nelson and the battle of Trafalgar (which occurred in October 1805), Napoleon’s armies which had earlier massed along the channel coast threatening invasion of England were already marching east and into Austria. He caught Austria by surprise and surrounding one of its armies at Ulm he won a resounding victory. This was soon followed by the capture of Austria.

Soon though Russian armies began arriving and together with the Austrian forces these now outnumbered the French. The Prussians were making noises suggesting they might also join the war against Napoleon so he realized he needed a quick and decisive victory.

He managed to trick his enemies into believing that he was weak and that at the end of long suply lines was vulnerable. The ruse worked and the Austrians and Russians converged at ground Napoleon had chosen.

The essential elements of the battlefield were a central raised ground called the Pratzen heights and lakes and streams forming a barrier on the French right (allied left). The route to Vienna and Napoleon’s supplies were south (beyond that right wing). Napoleon decided to deliberately weaken that wing and to hide the bulk of his armies in the mist and fog covered dead ground beneath the Pratzen heights. Then he sent word to his best general – Davout – to march with all speed from Vienna. Davout had two days to cross 68 miles but napoleon was confident that Davout could achieve this. Assuming Davout could arrive Napoleon would have 72,000 men to fight 85,000 allies.

Just as the French leader hoped, the Allies attacked the weak French left wing. Napoleon allowed his enemy to become committed and then launched an assault by Marshall Soult on the center – right over the Pratzen heights. As the French attacked the sun broke through and boiled away the mist. The sight of 20,000 French attacking in dense columns up that hill and emerging from the fog must have been terrifying. The “sun of Austerlitz” went down in history as one of the memorable elements in the day.

The battle reached a critical point. With their center crumbling the Russian and Austrians committed the Russian guards division in a counter attack that require Napoleon to respond by deploying his Imperial Guard. The French guard won the day and the allies center was rent asunder. At this moment Davout had arrived and using these new men Napoleon moved against the over extended Allied left, routed them and drove them onto the Frozen lakes to their rear. It is unclear exactly what happened next. It is possible that the French opened fire on the ice plunging thousands to an icy grave. Other accounts had the French rescuing their enemies from the ice. IT suited the Czar to believe that the catastrophic losses to his armies were caused more by nature than enemy tactics and so he accepted the story of his armies drowning. After the battle the lakes were drained and actually not that many corpses were found so it is likely that the story of the frozen lakes claiming thousands is not fully true.

What is true is that outnumbered, Napoleon had defeated the enemy by guile and strategy. He has lost no more than 8000 dead or wounded to 25,000 allied losses or prisoners. The defeat knocked Austria out of the war and they made peace. Napoleon moved north to take on Prussia and pursue the retreating Russian armies.

Austerlitz became part of Napoleon’s legend and as much a great memory for Frenchmen to recall as Agincourt or Waterloo became for the British.