Richard Denning's Blog, page 10

September 23, 2012

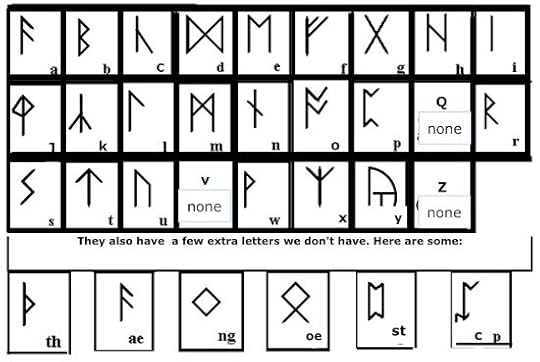

Anglo-Saxon Runes

When the ancestors of the English came to Britain they spoke Old German which soon evolved into Old English . Little of their writings survives but what does was written in a Runic alphabet called the Futhorc after the first letters of their alphabet.

The Old English Futhorc originated from the Elder Futhark – the original runic alphabet developed and in use by the German tribes in the early centuries AD. The English tribes brought it to Britain but as the years went by their language and sounds altered. (Linguists call this the consonant shift and is why for example Ein Bett in German becomes a bed in English). With this cam ethe need for new letters to reflect those sounds.So the Old English Runes changed from the German with use.

Here (in modern alphabetical order) is the Runic alphabet:

The Runes were in use from the earliest days of the English settlement as demonstrated by a bone dug up dating to the 5th century with a single word “Rohain” meaning from a Roe written upon on it in Runes:

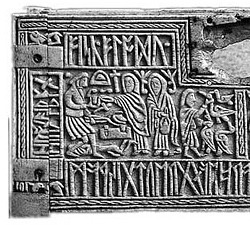

The eighth century British Museum Franks casket, which is believed to be from Northumbria, exhibits the runes as well as telling the tale of Wayland the Smithy of the gods and other sagas:

The Seax of Beagnoth was found in the river Thames in 1857 and dates to 9th century. Inscribed upon it is a complete 28 character set of the FUTHORC or old english runic alphabet. It also contains the name of the blades owner.:

The Runes began to be replaced by Latin characters in the 7th century with the coming of Christianity following the Augustine mission of 597 AD but were maintained in use in monasteries right through to the Norman conquest when they fell out of use even as a historical curiosity – probably all part of Norman suppression of English traditions.

September 14, 2012

Anglo-Saxon Days of the Week Part 5 – Friday

This week I am looking at the names we give our weekdays and the links to Norse and Anglo-Saxon mythology. Click the following links to read about Sunday and Monday , Tuesday , Wednesday and Thursday. Today it is the turn of Friday.

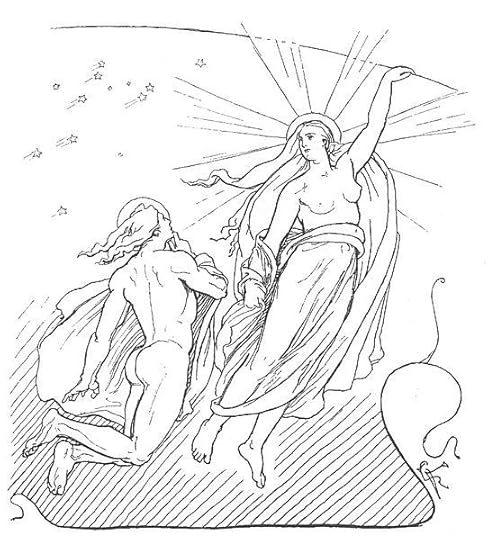

Friday in old English is Frīġedæġ the day of Frigg.

Frigg or Frigga/ Frige was the goddess of love and a parallel to Venus from whom we get Vendredi in Latin languages.

Frigga was the wife of Odin and Queen in Asgard. She was seen as the goddess of family and home and women. She is prayed to during child birth.

Frigga played an unwitting part in the death of Baldur brought about by Loki. Baldur was immune to all attaches but, in disguise, Loki asked Frigga if ANYTHING could halm him. Frigga confessed that a spear made from Mistletoe would hurt him. Loki arranged for another god to throw the spear and so Baldur was killed.

The Norse name for the planet Venus was Friggjarstjarna meaning ‘Frigg’s star’. Orion was called known as “Frigg’s Distaff/spinning wheel” (Friggerock) or sometimes as ”Freyja’s Distaff” (Frejerock).

This is the end of this little series. Why no Saturday? Saturday is the only day of the western/ English naming system that comes from Latin – in this case Saturn’s day. What would the Saxon have called Saturday. Well the old English for it was sunnanæfen which equates to modern German Sonnabend or Sun’s eve. The day before Sunday. Which brings us full circle to where we started in part one.

Hope you enjoyed this little series of blogs. Find out more about the Early Anglo-Saxons and their beliefs in Shield Maiden and The Amber Treasure

September 13, 2012

Anglo-Saxon Days of the Week Part 4 – Thursday

This week I am looking at the names we give our weekdays and the links to Norse and Anglo-Saxon mythology. Click the following links to read about Sunday and Monday , Tuesday and Wednesday Today it is the turn of Thursday.

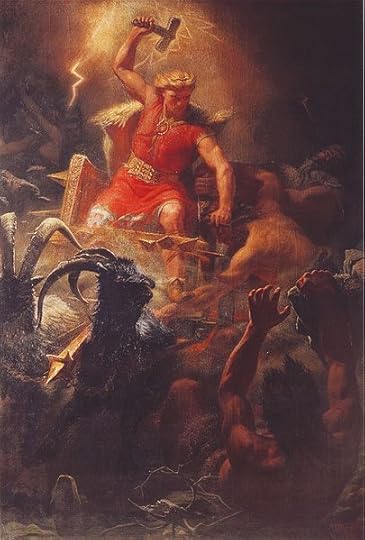

Thursday in old English is Þunresdæg . But don’t go around thinking that is a P at the start. It is actually the “thorn” rune or symbol and represented a “th” sound. It originally meant Thunor’s day. Who was Thunor? Well in the norse dialects they dropped the n and the o to make it Þorsdagr or Thorsday. So yes – Thursday is the day of Thor. The Anglo-Saxons called him Thunor but they are one and the same. The original German name was Donar meaning lightning. In Germany Thurday is Donnerstag.

Thunder is of course one of the main elements associated with Thor. He as he god of thunder and lightning and of strength. He is also associated with oak trees and fertility. He possess two artefacts of great power. One is a belt that makes him even stronger. The other is Mjolnir his great hammer with which he is mighty in battle.

A god of great strength as demonstrated by this image when the other gods cross a river via a bridge but Thor just wades across it.

The Norse and Anglo-Saxons often wore his symbol around their necks. What other symbol than a hammer could represent him?

The Norse and Anglo-Saxons often wore his symbol around their necks. What other symbol than a hammer could represent him?

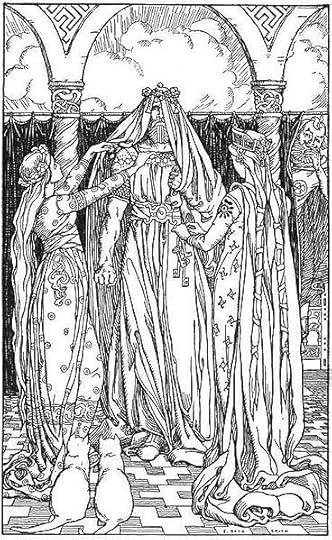

The sagas are full of tales of his bravery, strength and sometimes cunning. There is one tale when he disguises himself as a woman to infiltrate the kingdom of the Giants.

The sagas are full of tales of his bravery, strength and sometimes cunning. There is one tale when he disguises himself as a woman to infiltrate the kingdom of the Giants.

Thor is supposed to finally die in combat with the great Midgard serpent.

September 12, 2012

Anglo-Saxon Days of the Week- Part 3 Wednesday

This week I am looking at the names we give our weekdays and the links to Norse and Anglo-Saxon mythology. Click the following links to read about Sunday and Monday and Tuesday. Today it is the turn of Wednesday.

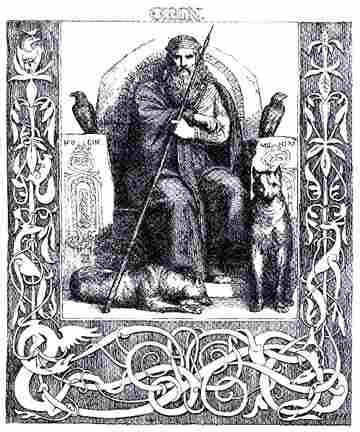

The old English for Wednesday is wōdnesdæg or day of Woden.

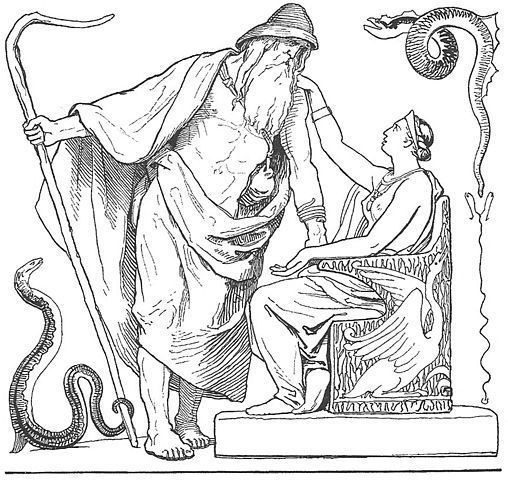

Woden (Called Odin by the Vikings and Woden in England) is the chief of the gods. He is a god of wisdom and thought and fate but also a war god. He appears as old man with a long beard. Has only one eye so wears a patch. He gave away one eye in order to receive the gift of wisdom.

Woden can make the dead speak and change men’s fate and destiny – their wyrd. He carries the spear, Gungnir, which never misses its target, the ring Draupnir, which can make other rings to give as gifts and he owns the eight-footed horse Sleipnir which can ride fast through all the Nine Worlds of the Germanic universe.

Woden has two Ravens Huginn and Munin (Thought and Memory)who fly across Midgard to tell him what is happening. He also has two wolves, Freki and Geri. It is said that half of those who die in battle are taken to feast with Woden until the end of time in the halls of Vallhalla.

In England many villages and towns such as Wednesbury (Woden’s fort/ fortified town) are named in his honour as well as the middle day of the week.

Find out more about the Early Anglo-Saxons and their beliefs in Shield Maiden and The Amber Treasure

September 11, 2012

Anglo-Saxon Days of the Week Part 2 Tuesday

Yesterday I started a look at the names we give our weekdays and the links to Norse and Anglo-Saxon mythology with a blog about Sunday and Monday.

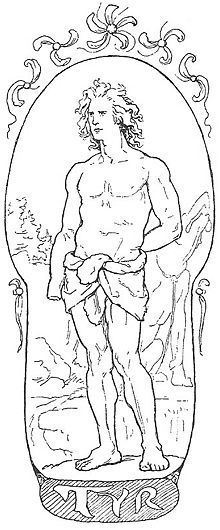

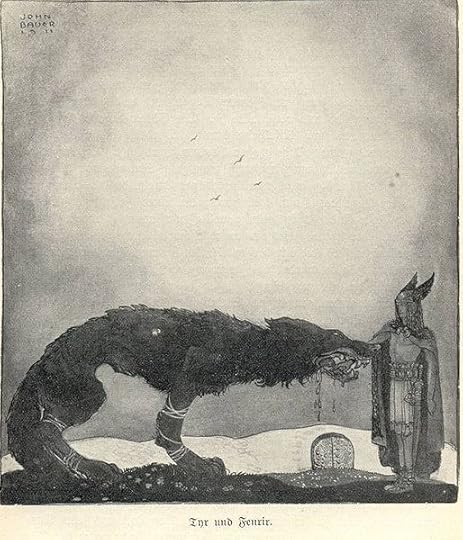

Tuesday in old English is Tiwesdæg or ”Tīw’s Day”, the day of Tiw. Tiw – or Tyr as he is sometimes called is the Germanic god of single combat and heroism. He is the equivalent of the Roman god Mars and indeed in the latin calendar this day is dies Mars (the day of Mars)

Tiw/Tyr is portrayed as having one hand:

This is because according to legend as recorded in the Edda (the Icelandic books containing the sagas and tales of the gods), Tyr lost the hand in an encounter with the wolf Fenric. Fenric was running amock and resisting all attempts to be bound. He eventually agreed to be bound IF one of the gods would place their hand in his jaws. Tiw agreed and it was bitten off but Fenric was bound (and will remain so until Ragnarok).

The old english Tiwaz rune (the T rune) is associated with Tiw.

This rune is found on more pots of cremated ashes in burial grounds than any other – perhaps fallen warriors on their way to Valhalla: the pagan Anglo-Saxons putting their faith in the brave warrior god.

Find out more about the Early Anglo-Saxons and their beliefs in Shield Maiden and The Amber Treasure

September 10, 2012

Anglo-Saxon Days of the week Part 1 Sunday and Monday

The next few days I am going to have a look at the names we give to the days of the week. These names demonstrate the profound effect that the Germanic and Anglo-Saxon mythology had on development of western culture. Of the 7 days of the week all but one of them relates to a Old English/ Norse / Germainic god or godess.

Because they are linked (as we will see in a moment) I will start with Sunday and Monday together.

The old English name for Sunday was sunnandæg (“day of the sun”). All the Germanic and Scandinavian words have the same root. The Old English name for Monday was mōnandæg (“day of the moon”).

The Germanic people who developed these names were not just thinking of the physical sun and moon. They believed in a goddess Sunna who carried the sun through the skies behind her chariot. Sunna’s brother was Mani and it was he who carried the moon through the night skies.

The sun and the moon are always in motion and Sunna and Mani can never rest for after them, galloping through the clouds are two wolves. Scholl is the wolf that chases after Sunna and Hati is the wolf which pursues Mani.

At the end of the world – at the time of Ragnarok the wolves will catch up and devour the sun and the moon.

How do we know these stories?

The stories are recorded in the Edda and other Scandinavian poetry/. Further more statues of the sun on a chariot have been found.

September 9, 2012

The battle in the Teutoburg Forest – German Tribes destroy the Romans

The 9th of September in the year 9 AD is of great significant to the history of both the Roman armies and the Germanic tribes. On this day an alliance of six German tribes annihilated three entire legions of Romans along with several cohorts of auxillaries in a battle deep in the vast forest that covered and still cover much of Germany. It was a battle that at times has been used by the Germans in the same way that Britain might talk of Waterloo or Agincourt when stiring nationalist sentiments.

Roman Expansion in Germany

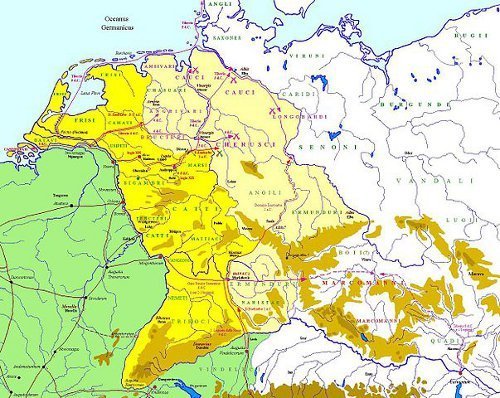

The Romans had been pushing out across from the Rhine, conquering tribe after tribe for 20 years in a series of campaigns. Thus in 9 AD the Roman Empire controlled, directly or via subservient and allied states, a huge area of western Germany as far east as the River Elbe.

The Romans had been presented as a hostage and tribute the young son of a German tribal leader. This boy was Arminius. He was taken to Rome and raised as a Roman, even being given a Roman military education and a rank. Secertly though Arminius was an enemy of Rome and when he returned to the Rhine and became a trusted advisor to Varus, the Roman commander, he began putting together plans for a betrayal. He contacted the various tribal leaders under the dominance of Rome and found that due to Roman brutality there was a strong appetite for a rebellion.

Statue of Arminius

When all was ready Arminius fed Varus a false report of an uprising North of the Ruhr river. Varus mobilized all his available troops - maybe 36,000 men and began to march to the area Arminius suggested. He was able to lead Varus along a path that led deep into the Teutoburg Forest near Osnabruck.

The path was narrow and Varus was obliged to stretch out his formation over 20km. This was the moment Arminius and his allies had been waiting for.

The Teutoburg forest

Around 30,000 German tribes men emerged from the forested and assaulted the Romans. The Battle would last 3 days with the Romans managing to build over night fortresses and march on. IN the end the path they followed brought them in front of another fortification - but this time built (at the suggestion of the Roman trained Arminius) across the Roman path. Assaults on this fortification failed and the Roman army broke up in dis-array with victorious Germans running amock amongst them.

Many Romans took their own lives including Varus but hundreds were taken prisoner. (Some being eventually rescued by the Romans in a later raid 40 years later!)

Aftermath

The battle – leading to the loss of three legions including their eagles and 36,000 men – crushed Roman authority east of the Rhine. Virtually all the territory they had taken was lost. Augustus Caeser was distrught – apparently banging his head against a wall and shouting ‘Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!’.

The Romans would attack again east of the Rhine about 5 years later and exact terrible revenge in a number of bloody raids. They would retrieve their lost eagles, rescue captives and even bury the bones of the dead they found strewn over the battlefield in the forest BUT they never again conquered these lands.

Nationalism

Over the centuries THIS battle was been evoked by the Germans at moments when a sense of German nationhood was desirable. In 1808 with much of Germany under the control of the Eagles of Napoleon’s French Empire plays were made of this battle – and it was clear that although the enemy was Rome a parallel was being made with the French oppressor.

The battle was later used in propagana in the wars of German unification against Austria and France in the 1860s and 1870s BUT in the post WW2 era has been ignored as the Germans tended to avoid overt displays of national pride.

September 8, 2012

Origins of the English

The English, England – from where does the name of the language, people and land come and what does it mean? To answer this we have to travel back to the first century or two after the birth of Christ.

The ancestors of the Angles came from Angeln in Germany - image from http://primaryhomeworkhelp.co.uk

At this point – around A.D. 100 we get the the first mention of a tribe called the Anglii in a book called Germania written by a Roman historian called Tacitus. It is believed to be a latin version of a German word Angeln. This word probably meant ‘anglular land’ or ‘peninsular’ – the part of the land they came from from all accounts looking a bit like a fish hook.

In later years Bede (the great chronicler of the rise of the English nation) writing in the 8th century identified the land of Angeln as being between the Jutes (basically modern Denmark) and the Saxons of Saxony on the Elbe river.

Today a small peninsular in northern Germany is called Angeln still.

Thus the original homelands of the Angles is likely to be the this small bit of land on the borders of Germany and Denmark. Interestingly Bede says that this land was depolulated by the emmigration and was unpopulated in his time. Furthermore there is almost no mention of the Angles IN EUROPE after the period of Anglo-Saxon settlement of England in the 5th to 7th centuries. For some reason – perhaps pressure from encroaching tribes from the east, pretty much the entire population may have upped sticks and crossed the North sea.

So where did these tribes go to? Well the whilst the fellow Anglo-Saxon Tribes the Jutes settled Kent and Hampshire and the Saxons most of the rest of the south the Angels headed for three lands:

Northumbria (becoming the Deirans along the Humber and Yorkshire and Bernicians around Bamburgh). This may well have been a very early phase in the 5th century. Possibly it occurred in relation to the call by the Britons for mercenaries to fight the Picts. It is possible that many Angles moved to this area when it was still under Roman control.

East Anglia – where they divided into the North Folk and the South Folk from where we get Norfolk and Suffolk.

Mercia – the midlands of England. Mercia means the land on the border. This was the border between the Angles and the Britons. This settlement was later than Northumbria – probably the mid 6th century.

Once in Britain the Angles fought each other, the Saxon tribes and the Britons or Welsh for centuries. The Vikings would conquer much of the land and merge with the English. The road to a single people – the English would take hundreds of years and it is not until the times of Alfred the great, his sons and grandsons that we finally have kings acknowledged as king of the English. Even then much of the land we call England was under the rule of the Vikings.

The names England and English corrupted over the centuries via Angeln, Angleland to England and the Angeln became the Anglish and then the English.

What’s in a name

So England is the land of the Angles – the land of the folk who came from Angeln.

But there is another twist to the word. In old English place names Eng or Ing also means ‘People of’ Thus Birmingham is settlement (ham) of the people of (ing) of Beorma (a man called Beorma).

So another version of England is that it means “Land of the People”.

This article is linked to another - How a Knife became the name of a people where I explore the origins of the Saxons.

September 6, 2012

How a knife became the name of a people

The seax is the name given to a particular long bladed knife associated closely with the Saxons – the tribe of Germanic peoples that originated in the area we called lower Saxony today and who migrated inthe 5th and 6th centuries to Britain. They settled in the south east.

Europe in the late 5th century. (From Creative commons)

The knives gradually grew larger, and broader. They are sometimes straight, sometimes curved but all tend to have a single edge and often a broken back. Why are they so significant? Well for one thing some of the examples that have been found over the years have helped us understand WHERE the Saxons migrated to as they have been found in burial sites, the dating of which sheds light on the progress of the spread into Britain.

My own seax

Furthermore one particular seax has helped us understand the runes used by the Anglo-Saxons. The Seax of Beagnoth was found in the river Thames in 1857 and dates to 9th century. Inscribed upon it is a complete 28 character set of the FUTHORC or old english runic alphabet. It also contains the name of the blades owner. Whoever Beagnoth was he must have been rich and also I imagine very irritated to loose such a fine weapon.

What though did I mean by a knife becoming the name of a people. Well this is of course the Saxons. The very word means “Men of the Seax” or “Men of the sword”. A race who adopted a weapon and in time were named after it. The use of Seax as the name for a blade still lingers today in the word Sax, Sack or Zax which is a roofers tool for cutting tiles.

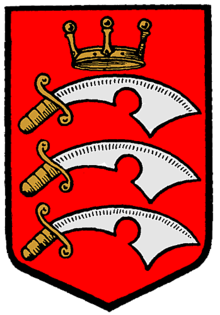

In time the Saxons merged with the Jutes and Angles and became Anglo-Saxon and one day the English but their name lives on in that of several English counties: Sussex, Middlesex and Essex (once the lands of the South-Saxons, the Middle-Saxons and the East-Saxons.) The old Kingdom of Wessex was the lands of the West-Saxons.

As a faint reminder of the origins of their names two of these counties still show a seax in their coats of arms.

Coats of Arms of MIddlesex:

Flag of Essex

I own a seax as well as a Saxon sword and a number of items of clothing and armour. I am happy to visit schools as well as historical societies to talk about them, the Saxons and my books that cover this fascinating period.

August 21, 2012

Battle of Wagram 1809 The Emperor Strikes Back

In my article yesterday I looked at the Battle of Aspern Essling on 21st and 22nd May 1809. Having defeated the Austrians in Bavaria and gone on to capture Vienna, Napoleon was trying to cross the Danube from Vienna to engage the Austrian army under Arch Duke Charles in an attempt to finish the war. There in the confined space between the villages of Aspern and Essling a ferocious battle ensued but he was unable to break out of his bridghead and suffered his first ever defeat. He was obliged to retreat back over the river leaving 25,000 French dead or wounded on the far bank: one man in three!

6 Weeks later in early July he was ready to try again. What would occur in the next 48 hours would be the greatest battle in history at that point with 300,000 men under the eagles of France and Austria fighting a climatic struggle that neither could afford to lose.

Day one 5th July

Mindful of the failures of the earlier crossing attempt Napoleon personally overseed much of the plans for the new crossing. On the night of the 4th July operations began. The French made use of pre built bridges that were swung into place and also landing craft and boats.

Quickly and in an organised manner three Corps were across the river and soon pushing out through Essling and Gross Enzersdorf and beyound on to the vast featureless plain called the Marchfeld. Initially Austrian resistance was light and the two Corps they met fell back in good order. Eventually the French located the main Austrian army positioned on a elevated plateau 20m above the surrounding flat plain and in three villages ( Deutch-Wagram, Baumersdorf and Markgrafneusiedl) built in front of the ridge and behind a wooded stream called the Russbach. This high ground was called the Wagram.

Napoleon now had 160,000 men on the Marchfeld whislt Charles had 140,000 on the Wagram and to the west near the Bisamberg.

It was 6pm of the 5th July and the Austrians assumed the battle would occur the next day. Napoleon had other ideas and ordered an assault on the Wagram. This attack went in between about 7pm and 10pm all along the front but the Austrians fought well and repelled all assaults although near Deutch-Wagram the attack almost broke through were it not for Arch Duke Charles personally leading a counter attack. Additional confusion threw Napoleon’s troops into chaos around Deutch Wagram being caused by the white uniformed Saxons (French allies under Bernadotte) between mistaken for the white uniformed Austrians and fired upon by the French!

It was now full dark and the assaults were called off whilst Napoleon considered his plans for the 6th.

Napoleon held a planning meeting with his generals on the night of the 5th July

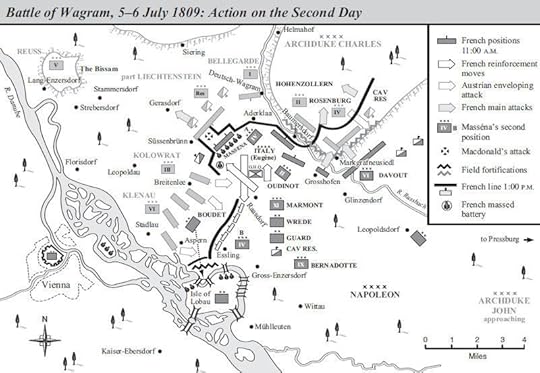

Napoleon’s plan was to hold the Austrians along the left of the Wagram and on his left wing whilst Davout’s veteran Corps swung around the right wing captured Markgrafneusiedl and the tower on the Wagram above it and rolled up the flank.

It was not only the French who made plans that night. Charles knew he was out numbered but he had two Corps in his pocket. II and VI corps were to the west and could march to come around through Aspern and Essling and surround the French. If he could pull this of he could annilhilate the French invader.

The Second Day

It was Charles who got his plans moving earlier and around 4am that day Napoleon looked with horror to the west as two Austrian columns marched towards his lines of supply. Meanwhile Austrian I Corps under Bellegarde (supported by cavalry under Lichtenstein )attacked from Deutch Wagram and captured Aderkla which was at the hinge between the north facing French facing the Wagram and the west facing corps.

If Austrian VI Corps had just kept marching it would be an utter defeat for Napoleon. BUT the Austrian command structure had a fatal flaw. They obeyed orders to the letter but had no capacity for innovation and initiative. Klenau (VI Corps) orders were to reach Aspern and wait for more orders. Ahead of him was empty space and the French supply lines. But he did not attack and the moment passed.

Napoleon had to put his plans on hold and react to Charles plan. He sent Massenna south and west to try and block the Austrian III and VI corps . To mask that move and hold off the pressure from Bellegarde and Lichtenstein he resorted to desperate measures. His cavalry reserve including his precious guard troops were flung into near sucical frontal charges against dense masses of Austrians. A French Corps under Macdonald formed a huge square and pushed west suffering 2/3rds casualties. Finally 150+ guns were assembled into a grand battery and rolled along on Macdonald’s flank to blast the Austrians. This was attritional warfare at its most horrific and the death toll on both sides near Aderkla and Deutch-Wagram was monumental.

Nevertheless it worked. Massenna was able to maneuver in front of the Austrian attack. The French left wing held and now,finally, around noon Davout’s veterans delivered the right hook. Charles rushed over to lead reserves in an attempt to block the attack but Markgrafneusiedl and the tower fell. It was clear his plan had failed and so in order to save lives he ordred a general retreat around 2.3opm. Napoleon pursued but Charles made good use of cavalry to let the infantry march away.

Casualties at this battle were around 35,000 on each side, perhaps 1 in 4 men engaged being killed, wounded or missing. It was a bloody battle and Napoleon felt it had not been decisive as the Austrian army survived.

Never the less the victory went to the French and following another engagement (much smaller) a week later Charles made peace. He had not consulted the Austrian Emperor and he was forced to retire but his actions saved many lives.

The Battlefield Today

Apart from the southern part near Aspern and Essling which is within Vienna the bulk of this battlefield was and is a vast open plain dotted with villages with the most interesting terrain being around the Wagram.

The Marchfeld is incredibly flat and featureless for the most part:

Looking north from Gross Enzersdorf - this is the ground the French marched over towards the Wagram

The Russbach stream, still wooded, open space to the north and the modest elevation of the Wagram is easy to find:

The Wagram is really little more than a slight elevation over the surrounding plain:

At Wagram there is a superb museum:

At Wagram there is a superb museum:

South east corner of Deutch Wagram - the museum is on the left. The French tried and failed to take this town on the 5th

There is a Memorial at Aderklaa

The village itself is peaceful today but was the heart of the battle on the 6th:

The fields to the south of Aderklaa where Macdonald’s square and the Grandbattery attacked from left to right (we are looking south):

Finally this is the tower that was attacked by Davout that fateful day:

Finally this is the tower that was attacked by Davout that fateful day:

If I get back I will revisit Wagram as armed with a book and map you can locate the spots that the actions occured at. It is easy to see how the losses were so high as in many spaces there is just no cover at all.

If I get back I will revisit Wagram as armed with a book and map you can locate the spots that the actions occured at. It is easy to see how the losses were so high as in many spaces there is just no cover at all.