Eamon Loingsigh's Blog, page 18

January 22, 2014

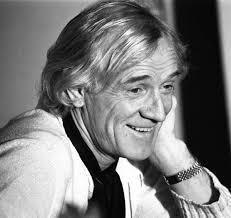

Malachy McCourt reads from ‘Diddicoy’ (text included)

Well, if you are wondering what “Light of the Diddicoy” reads like, here is a master storyteller to relate it to you. Mr. Malachy McCourt reads from Chapter 12 called “The Runner.” Below is the actual text, if you would like to read along:

Loaded with moon-faced Italians, Sackett, Degraw and Union Streets in Red Hook are dangerous places for a kid like me to wander among. So I don’t complain about not being sent to Red Hook as I avoid all Italians at any cost since they eat their own babies, Vincent Maher tells me, and if you cross them they’ll chop up your mother ten years later (because they have the memory of elephants) and make meatballs out of her and serve her up with pasta and red sauce down in Bay Ridge because, “they’re all a bunch o’ pagan Catholics, fookin’ animals,” Vincent says.

[image error]

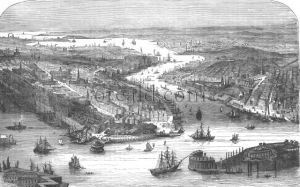

Manhattan Bridge under construction over Brooklyn’s “Irishtown” where the White Hand Gang had its headquarters.

In the Navy Yard, men build ships paid for by the government contracts and this is wartime, so business is good. England is buying and as far as the manufacturers in Brooklyn are concerned, there should always be wars. All day and night long steam hammers slam down on hot iron slabs in the Navy Yard foundries. And you can hear the pound of them all the way over at 25 Bridge Street (the White Hand Gang’s saloon and headquarters), even making ripples in Ragtime Howard’s whiskey glass. When I yell up to Red Donnelly to ask if he needs any messages sent, he just waves his hat in the air revealing his red hair and fat head atop a barge where he directs cranes and bellows at his boyos.

The floating piers and pier houses at the terminals under the bridges like Jay Street and Fulton Street have industrial freight tracks dug into the Belgian brick that runs along the waterfront. Cargo is hauled from ships to floating piers to railcars that amble in

their clicking and their clacking through the neighborhood and pull up at warehousing units where the train cars butt against the platforms and where men with suit and tie and hats of all sort unload them by hand or by bale hook in the morning sun. It is there, under the bridges, that Cinders Connolly always shakes my hand and speaks to me like a man, smiling humbly as he is known to and with a mean set of crooked teeth and scabbing knuckles.

The terminals at Atlantic and Baltic take in shipments that mostly go onto automobile trucks to be driven over the bridges to Manhattan or east toward Queens or Long Island and wherever else, as it’s New York’s piers and the piers only that all goods are shipped since it is well before roads connect the cities to the farms and also before planes are to fill the skies. And everyone knows that it’s New York that is the center of the industrial world, now surpassing even old London town with the completion of the Erie Canal years ago.

Sketch of 1916 Brooklyn-Irish mugshot by Guy Denning (http://guydenning.org)

At Baltic Street, Gibney “The Lark” speaks with me in a serious tone and I never seem to realize that it’s all a front as Big Dick Morrissey comes behind me and picks me up. Spinning me upside down, he dumps me in a garbage can so everyone can have a laugh. But when he’s not looking, I punch him in the stomach as hard as I can, though I’m never able to knock the wind from him.

“See, ya don’ wanna go to Red Hook anyhow,” Vincent says. “Il Maschio is down there. That’s trouble. Real trouble.”

It interests me greatly though, Red Hook, and so I ask around about it. In fact, asking questions becomes what I am known for and it is more than once I am told to “shaddup.” But because I have the hunger for knowing things, I never take it the wrong way. Beat McGarry tells me it’s the incumbent Irish that have run Red Hook for many years, but is now overflowing with immigrant Italians. Frankie Yale knows the value of the area and so he often sends in Il Maschio to remind the pier house supers and the stevedoring managers that it’s only a matter of time until the Italian Black Hand takes over.

“Who is Il Maschio?” I ask, but nobody knows. No one. If he’s a man or a group of men, no one can answer me since it, or they, slink in the shadows and when the clean-shaven Irish show up he, or they, vanish like they never existed, or he never existed. Maybe like they exist everywhere, or he does maybe.

A Brooklyn Bridge worker peers through the darkness.

“What’s the Black Hand and what does Frankie Yale have to do with black hands and Il Maschio” I ask Cinders Connolly, but he won’t say.

“What does Il Maschio mean in Italian?” No one’s sure, but Dago Tom tells me it means “the mail.”

“Like sending letters, like?” I ask. “The postal service?”

“No, like ‘man.’ Or ‘boy.’ ‘Male,’ ya know? Male?”

“Oh, that kind of male,” I say.

Somewhere I learn that Il Maschio is Frankie Yale’s wing of Italian thugs, or thug, who work on the docks and believe in something called “the SicilIan Code” and that if they can’t reach your mother, they’ll kidnap your child for ransom. And if you talk to the police or anyone else, the child will end up in a barrel at the bottom of the Gowanus Canal. And I learn too that Il Maschio only appears when the Irish fight amongst themselves, which happens often or when the dock boss is sent to Sing Sing or the workhouse, which also happens often. And since I can’t get straight answers about Italians, and I’m filled with strange stories I sense that there is mystery around their ways, even if they are Catholics like us. They are a mysterious people and since they show up only when we are fighting among ourselves, I sense that they must be in cahoots with the pookas from the stories of my childhood. But then, I am starting to get to the age where the validity of the old stories become questionable and that only confuses me more.

I think of my father and his quips, and though he was speaking of the British being preoccupied with the German, he used to say, “With your enemy’s turmoil come opportunities,” and so it is in Brooklyn with the Italians. Before being sent up to Sing Sing, McGowen had long been charged with controlling Red Hook for Dinny Meehan (White Hand Gang leader). But a couple months after McGowen was sent up, Dinny came under great pressure to take the area by force as it had been coming under the influence of Il Maschio in McGowen’s absence, since that’s when the Whitehanders are most vulnerable.

January 18, 2014

Barrow Street Theatre-Reading

Before the show, Malachy told me some old stories including the one about my own surname that he knew from when he was told in his childhood in Limerick, Ireland.

What an incredible evening. I am really finding myself to be quite possibly the luckiest writer on the circuit. After arriving in the city, I hung around Greenwich Village and visited the old haunts of my grandparents and great-grandparents at 463 Hudson Street, the saloon that was in my family from 1906 to the late 1970s. A bit nervous about the reading, I had a few drinks while listening to some city workers and off-duty firemen grumble and bluff with thick accents and hearty laughs.

It’s called Barrow Street Pub now and it’s just a few blocks down from the Barrow Street Theatre where the reading was to take place. The bar is close to the water on Hudson and Barrow where the old longshoremen of New York City used to hand over their paychecks to my great-grandfather behind the bar back during the times when Light of the Diddicoy takes place, 1915 and 1916. Later in the week, the longshoremen’s wives would come to the bar for the rest of the money. My great-grandfather Thomas Lynch, his wife Honora Lynch (nee Kelly) and their six children resided in traditional fashion, upstairs from the saloon.

I often visit the old place, which is still kind of rough around the edges. As mentioned, I had a few butterflies to kill and felt a little better after a drink or two and some texting with close friends and family.

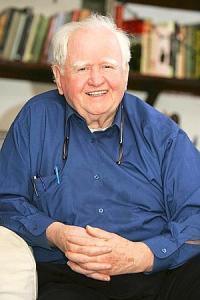

When I walked into the Barrow Street Theatre an hour before the reading was to start, I saw Malachy McCourt up on stage with his cane. His command of the English language still at its peak and the charm of an old storyteller has settled in him nicely. I climbed up to be with him and after listening to him, the butterflies had disappeared entirely.

“Do you ever get nervous, Malachy? Before going on stage?” I asked.

“Well Eamon, no matther what happens, time will still pass. All these people here,” he pointed at the crowd while speaking in his wonderful brogue. “They’re here for a good time, my bhoy. Are they not? Life will end whether we want it to or not, so we all just need a little joy, don’t we?”

“Yeah, we sure do,” said I.

I couldn’t have asked a better man for advice as he has seen and done just about everything a man of the stage could do during his time. On and off Broadway, Hollywood movie roles, a regular on Johnny Carson, a saloon owner himself and author of the rollickingly hilarious A Monk Swimming, one of my all-time favorite books told in his own voice, which is to say the oral tradition of the Irish.

Maybe one day I’ll earn the right to have eyebrows like Malachy McCourt.

Just as I was to be called to the podium, Mr. McCourt and I began conversing on the story of the surname and adjective “Lynch.”

“Americans want to own everything,” Malachy says with a smile. “They can’t have Lynch though. I’ve often heard of Americans telling the story of some chap in Lynchburg, Virginia having originated the term “Lynch” as in hanging from a tree. ‘Tis not the case, Eamon.”

It was here that I ached to interrupt him and tell the story myself as I am well aware of the ancient version. But realizing it’d be better to hear him say it, I kept my gob shut and my ears opened.

“It comes from a Mayor named Lynch in County Galway who was forced the hang his own son, which was the penalty for murder for which his son had most certainly committed. I heard this story as a young boy in Limerick and it always stuck with me, Eamon.”

I only smiled and confirmed that I too knew the story, having read it on the wall of the lobby of Lynches Castle in County Galway years ago (Lynches Castle is now a bank, or was at least when I was there).

After the show, the usual compliments came pouring in, but a good literary friend who runs a blog and knows quite a few things about book publicizing said that he was glad to see Light of the Diddicoy getting the right kind attention.

And for that, I must thank Peter Carlaftes and Kat Georges of Three Rooms Press. I can’t seem to put into words the appreciation I have for all they have done for Light of the Diddicoy. “I see too many people doing it the wrong way,” the friend said. “You guys are really doing a great job getting the word out in a positive and dignified manner.”

Mr. Malachy McCourt as well, I must thank too. He has been a wonderful supporter both on WBAI Radio-NYC with me earlier in the week and reading from the book at the Barrow Street Theatre.

Also, I need to truly thank Richard Vetere and Israel Horovitz, because if it wasn’t for them the 200-seat theatre would hardly have been as filled as it was.

Isreal Horovitz also read from fellow Three Rooms Press author Richard Vetere’s new book The Writers Afterlife.

Mr. Vetere’s book, The Writers Afterlife (also from Three Rooms Press) is a smart and fun read, from what I’ve heard so far.

Thanks also to everyone who came and supported us and bought me Guinness at the old Lions Head bar (now called A Kettle of Fish) at the after party.

January 10, 2014

Cool Links

I thought I would take a moment to recognize some other websites and/or blogs that I have found to be informative, fun and overall extremely helpful if you are at all interested in history, New York and Irish/Irish-Americanism or any combination of these.

First off, here is the Old New York Page, which provides the coolest photographs about old New York. It updates daily, so you can always get a view of, say, Greenwich Village circa 1906 or the building of the Brooklyn Bridge of the 1880s. Really neat production on Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/TheOldNewYorkPage?ref=br_tf

The Wild Geese is perfect for anyone interested in their Irish background. Run by Gerry Regan in Queens, New York, it provides a forum  for discussion and has regular updates of blogs and articles about Irish history, literature film, the Irish diaspora, Irish-American history, Current events and anything you can think of concerning anything Irish.

for discussion and has regular updates of blogs and articles about Irish history, literature film, the Irish diaspora, Irish-American history, Current events and anything you can think of concerning anything Irish.

Brownstoner, which is essentially a Real Estate site for Brooklyn and Queens, has been a big supporter of us here at artofneed, Blog for the Auld Irishtown Trilogy. They are really big on anything historical about Brooklyn and have picked up a few of my blogs. Here they give a very articulate background of the Brooklyn neighborhood Red Hook and the New York Dock Company, which I couldn’t have said better myself. The NY Dock Co., as many of you know, features in Light of the Diddicoy as one of the gang’s enemies, although they do business together. Even if it is nefarious business (the company hired the gang to kill a labor organizer).

http://www.brownstoner.com/blog/2013/03/past-and-present-new-york-dock-company-warehouses/

LitKicks is run by a really smart and thoughtful literary enthusiast named Levi Asher. If you like to talk and read about classic literature, he specializes in the Beats, philosophical writing and any big news that breaks in the literary world. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he does not get snobby. His opinions are well thought out, empathetic and he is always open to criticism, and responds to it withenthusiasm instead of dismay. Something we sourly lack these days.

Fulton History was a humungous tool in my researching the White Hand Gang during their time. They provide numerous free newspaper articles from multiple sources that have been copied and uploaded onto the site. There are other sites that provide this service, but none are as user-friendly as this one.

Irish Holocaust – Not Famine. The Push to educate in facts – Is a Facebook page that has incredible detail concerning The Great Hunger, or what is commonly known as The Potato Famine of 1845-1852. I believe, as do many others, that this event is on par with the Jewish Holocaust of the 1940s, but because it had to do with the English (who many if not most Irish blame) and the Irish victims who did not want to speak of it, this incredibly important historical event has been shrouded in mystery, disinformation and all but erased from history books in school (I certainly wasn’t taught about it). This site puts forth the argument that since there was plenty of food in Ireland at the time (which was exported for English profit abroad), than it cannot be called a Famine. Instead, either holocaust, ge

nocide or extermination should be some of the adjective of choice here.

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Irish-Holocaust-Not-Famine-The-Push-to-educate-in-facts/95407379904

The Brooklyn Historical Society – This is not just a great place to visit, it also has a great site replete with photographs, personal histories and an archive of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

http://www.brooklynhistory.org

There are a lot of sites out there that are really great and were of great help to me, but they are already so big and popular already, they certainly don’t need me to promote them. Wikipedia in fact, was a very fast source for mostly accurate information. If I need to know what political Al Smith was doing in 1916, or the man in charge of Tammany Hall Silent Charlie, or where NYC Mayor Red Hylan was or who the district attorney for Brooklyn was or maybe even a quick rundown of the major fundraisers in New York for the IRB was, Wikipedia and a few other spots were always just a few clicks away.

See you on January 16th!!! Wait, you haven’t heard about it yet? Well, below is the flyer for you.

Eamon

December 24, 2013

Barrow Street Theatre

We have some big news to report here at artofneed, but first off, Happy Holidays to you all. I hope everyone is having good cheer with family and friends and able to enjoy these times.

Mr. Malachy McCourt, who knows a thing or two about the Irish, New York and their deep relations, has said some very wonderful things about Light of the Diddicoy.

Second, I’m sorry I haven’t had many posts lately. I just moved, and since this is the WORST time of year to move, I have been consumed with holiday planning and moving. I promise we’ll soon have a very fun blog up called The Gangs of Brooklyn, a look at the time frame from the Great Hunger through just before Prohibition (1845-1919). This blog ought to be a lot of fun for most of you.

In big news, famed author Malachy McCourt has thrown his considerable weight behind Light of the Diddicoy. In a recent quote, he said:

“Eamon Loingsigh’s book Light of the Diddicoy is an amazing series of literary leaps from terra firma into the stratosphere above. The writing embraces you, and his description of the savagery visited on poor people is offset by the humor and love of the traditional Irish community. Yes there is laughter here too and it is a grand read, leaving any reader fully sated. Don’t leave the store without this book.”

You CAN’T miss this… Nope

On January 16, 2014 Mr. McCourt (brother of Pulitzer Prize winning memoirist Frank McCourt) will actually read from Light of the Diddicoy at the historical Barrow Street Theatre! Very Exciting! You don’t want to miss it!

On top of watching Malachy McCourt read from Light of the Diddicoy, playwright, director and actor Israel Horovitz will read from fellow Three Rooms Press author Richard Vetere’s upcoming book The Writers Afterlife.

It’s going to be a huge night!

To reserve tickets, send an email here:

info@threeroomspress.com

The Barrow Street Theatre, located in the Greenwich House, is in the West Village of Manhattan at 27 Barrow Street.

Here’s a little bit about the Barrow Street Theatre - A 199 seat Off-Broadway venue located in the West Village, NYC operated by Producers Scott Morfee and Tom Wirtshafter. The building was originally opened in 1902 by progressives who sought to alleviate the poverty and over-population of the area during the time. With the vision of Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch, famous photographers like Jacob Riis gathered there to help immigrants adjust to city life.

I hope you all have a great holiday, and in the spirit of the Irish Christmas in New York, here’s a classic song and video from Shane MacGowan and The Pogues:

December 5, 2013

Reading: Bar Thalia

On December 3, I was lucky enough to read at the Irish American Writers & Artists Inc. Salon at Bar Thalia. The Upper West Side of New York City location was a perfect setting. Everyone in attendance was so generous and thoughtful to have listened so closely to the reading. I was very happy to hear compliments and interest in Light of the Diddicoy, the first book in the Auld Irishtown trilogy.

Lots of friends and supporters showed as well and I am amazed at how far this effort has already come. From the simple idea to write a book about my own family’s history as Irish American in Brooklyn to spending hours at the Chambers Street Municipal Archives alone in downtown Manhattan to inking a contract with Three Rooms Press and now reading the work in front of friends and strangers. It’s been a long ride, but the road is filled with great opportunity ahead.

There were some other readers there as well that were also very talented. I would encourage everyone with an Irish background or not to check out the wonderfully talented people at the salons held by the Irish American Writers & Artists Inc. They meet every other Tuesday night at Bar Thalia and the Cell Theatre. Here is a link for information:

http://www.i-am-wa.org/salons.html#

November 15, 2013

The Immigrant Story of Thomas & Honora Lynch

Note: This is a personal family history page. On this page we will detail as much as we can with as many sources as we can find, the life centered around Thomas Lynch and Hanora Kelly. Please send updates to add information to eamonloingsigh@gmail.com , if you would like to add any confirmed (or even unconfirmed) information surrounding this couple, whether it be years ahead of their arrival in while still in Ireland, or years after their emigration to New York City. Rumors, dates, photos, personal stories, bar room quarrels, supposed meetings with famous people, underhanded accounts… are all welcome and please do not hesitate in sending me an email. Everything you know and remember will be documented and kept well beyond my own years, so everything counts. I will do regular updates on this as I find more information and you send me information, so you can find this blog any time you like simply by looking for The Immigrant Story of Thomas & Honora Lynch on the right side of the page where it says “Recent Posts.”

Much of this information was pulled from ancestry.com. Look up “Alex Lynch Family Tree” or go here: http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/63377335/family . I believe you have to set up a “Free Trial” in order to look at it, but as long as you cancel the account within 14 days, you won’t be charged (theoretically). To open an account, you must put in a credit card number, so don’t be shocked.

Thomas Lynch was probably born in 1876 in Coolmeen, County Clare, Ireland and died on June 23, 1953. His father was Denis Lynch*1 (1825-1908) and his mother was Ellen Cunningham Kelly (1839-1926). His parents lived very long lives through Ireland’s greatest tragedy of what I will refer to as The Great Hunger (also named “Irish Potato Famine”). Thomas Lynch was the seventh child born of nine.

1) Delia

2) Denis

3) Margaret (1860)

4) Ellen (1866-1935)

5) Mary (1867)

6) Alice (1871)

7) Thomas (1876-1952)

8) James (1878-1955)

9) Michael (1882-1971)

It is not known exactly where Thomas’ mother, Ellen Cunningham Kelly was born, though it is documented that she died in Coolmeen, County Clare, Ireland 1/30/1926. She witnessed not only Ireland’s greatest tragedy in The Great Hunger, but also the Easter Rising of 1916, the War of Independence and the Irish Civil War where finally Ireland had gained independence over the majority of its territory, save six counties in the North, Ulster. Most likely, she would have met the face of Ireland in the 20th Century, Eamon de Valera who was the political representative from East County Clare and who, after the Easter Rising (he was not executed because he was born in New York) became Taoiseach and President of the Republic of Ireland.

Census of Ireland, 1911 – (Unverified source, names and dates do not match, which is common, but could very possibly still be the true family, see footnote*2) On April 2nd, 1911, per the documentation from the Census of Ireland, 1911” the people who were living with Ellen Cunningham Kelly (does not include address, unfortunately) were the following, including herself:

1) Ellen Lynch (74) – Widow (was married 52 years), born in County Clare, Ireland, current head of household, Roman Catholic, Farmer, with nine children still alive, can read and write, speaks Irish and English.

2) Bridget Lynch (daughter, 38) – Single, Roman Catholic, can read and write, speaks Irish and English.

3) John Lynch (son, 31) -Single, Roman Catholic, Farmer’s son, can read and write, speaks Irish and English.

4) (Illegible first name) Lynch- (son, 26) Single, Roman Catholic, Farmer’s son, can read and write, speaks Irish and English.

5) Mary Louise Clancy (grandchild, 4), Roman Catholic, cannot read.

Our Thomas Lynch made it quite difficult to pinpoint exactly what year he had emigrated from Ireland to New York City. Below is a graph of each Census year of New York and the year that he wrote when he emigrated. Try not to laugh at the inconsistency:

~1900 Census – he wrote that he emigrated to New York in 1889

~1910 Census – he wrote that he emigrated to New York in 1896

~1920 Census – he wrote that he emigrated to New York in 1897

~1930 Census – he wrote that he emigrated to New York in 1894

~1940 Census – Does not ask what year he emigrated

Because of this and his very common name, I am currently unable to verify specifically when he passed through Ellis Island, if he did pass through Ellis Island. There were quite a few Thomas Lynches on ship passenger lists from 1889-1897, so at this time it cannot be confirmed unless other family members come forth with other details.

Without confirming his date of passage, we next turn to the Census of New York, 1900 for a positive confirmation of his whereabouts in New York City. According to this document, Thomas Lynch is living at 318 West Street, New York, New York apartment #105 on June 8, 1900. This address is literally on the waterfront of the West Side of Manhattan where the current West Side Highway runs, just south of Houston and just north of where the Holland Tunnel currently is.

Thomas’ sister Ellen (32 in 1900), who was ten years older than him, had married Michael Mulqueen (34, Saloon Keeper) six years earlier and by 1900, they had a three year old son, Michael J. Mulqueen and a two year old daughter, Ellen A. Mulqueen. Also living at this residence as “boarders” are William Twoomey (35, Laborer) and Thomas McCarthy (32, Laborer). Thomas Lynch states here that he was born in October of 1878 and that he is 22 years old. That he originally came over in 1889 and is a “Laborer” and can read and write in English. To further confuse his arrival date in New York City, right next to the date of 1889 that he put as arriving, he wrote that he had only lived in New York City for one year. So, this may mean that he traveled more than once from Ireland to New York.

The two Mulqueen children were born in New York, everyone else at this address was born in Ireland.

It was very common in those days for new comers to stay with family in New York City. In Thomas’ case, staying with his older sister Ellen and her husband was probably a better choice than staying on the farm in Coolmeen, County Clare. Although Ellen and Michael Mulqueen both stated they only arrived from Ireland in 1897, Mr. Mulqueen is older, more established as a saloon keeper and considered the head of the household.

Young Thomas is not married at this time. According to my father, Timothy Lynch (1948-2013), Thomas Lynch was at this time working for the city, digging for the subways as a laborer. This is certainly possible, but not yet confirmed. What may also be possible is Thomas working at Michael Mulqueen’s saloon, although he probably would have stated that on this census. What is known is that Thomas Lynch will become a bartender and a saloon keeper himself one day.

Nora Kelly – Known as Honora, she was born in 1880 in Kildysart, County Clare, Ireland. From the stories that have been told to me, she came from a large and very poor family that sent her to a girl’s boarding school, or orphanage in the capital of Clare, Ennis.

Currently, there is no information on her father and mother, though we do know she had a younger sister named Anna (probably b. 1882) that was living with her in New York. Currently, Anna is the only other “confirmed” sibling. A family member reported to me that there were other siblings, including another sister named Teresa Rose Kelly. Two other brothers were born in New York, John and Joseph Kelly.

At some point, Honora was somehow able to leave County Clare, Ireland and get on a ship bound for New York. How she did so and how she met Thomas Lynch, hopefully, can be solved in the coming months.

In the Census of New York, 1910 (done on 4/22/1910), things have changed immensely for Thomas Lynch. He now lives and is renting at 93 Barrow Street, which is directly behind 463 Hudson Street (on the corner of Hudson and Barrow), the saloon he will own one day. His occupation is now “Dealer” and is an employee of “Siq Work” or “Sig Work” maybe “Sign Work”? He is still renting, but is now head of the household and married to Nora Kelly (30), who would be known throughout the family as “Honora.”

Thomas and Honora have two children Ellen M. (2) who was born Eleanor Lynch and Thomas Jr. (6 months old). But there are many others living in this address in Greenwich Village in 1910. Here is a listing:

Alice Lynch (40) who is described as Thomas‘ sister (b. 1871) and is a widow. She has five children that are still alive. She does not have employment, but does know how to read and write. This is the same Alice Lynch whose young child Mary Clancy will be living in Ireland with Alice and Thomas’s mother Ellen Cunningham Kelly in 1911, one year from now. Alice had married John Clancy sometime around 1891, though he has passed away by 1910. It seems odd that she would be named “Alice Lynch” instead of “Alice Clancy” even as her husband had died.

John Clancy (10), Alice’s son named after his father, was born in New York City. According to the letter I received from Dan Lynch via the Clancy’s, this John Clancy did not have a date of birth, which we can now assume to be either 1899 or 1900. He dies by 1924 however, of unconfirmed causes. He is one of five children born to Alice and John Clancy. Others: Helen (Hogan), Dennis (b. 1901), James (b. 1903) and Mary (b. 1906 in Ireland).

Anna Kelly (28, Single) – Who is described as Thomas Lynch’s “sister-in-law” which would make her Honora’s sister. Anna wrote that she arrived in New York in 1902 after being born in Ireland. She describes her occupation as “House work.”

Michael Hannon – (52, widowed) A boarder who was born in Ireland. He emigrated one year previously in 1909. He is currently a “Foreman” at a stable.

Orrin Herdman – (50, widowed) A boarder who was born in New York and so were both of his parents. He is widowed and is currently a Truck Driver.

Frances J. Barnes – (45, married) A boarder who was has been married for 22 years (wife not at this address though). He was born in Virginia, but both of his parents were born in Ireland. Currently he is a Produce Salesman.

Here in 1910, we have an extended family all living together. Thomas Lynch has already established himself as Head of the household and is married, having children, taking in boarders and working every day as a “dealer” of some sort in the neighborhoods just off the water. Coincidentally, 1910 is the year that New York became the largest port in the world, surpassing London. The docks off Greenwich Village and north in Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen are incredibly busy with freight ships and barges and the waterfront neighborhoods are packed with small businesses that benefit from the incredible amount of goods coming in from around the world. There is also quite a bit being manufactured in these neighborhoods as well, such as the soap factory on Washington Street right around the corner.

Thomas is also taking in his widowed sister, her son, and his wife’s sister to help with the young children (and is most certainly pregnant at this time too). Mr. Hannon, straight off the boat, could very possibly be a friend of the Lynch’s or Kelly’s back in Clare and two other boarders are staying as well, probably paying the majority of the rent.

One can only imagine what exactly a “dealer” is. It could quite possibly be a dealer in alcohol, or even a bartender. Living directly behind the saloon that Thomas will one day own, it’s hard to imagine him not working there in 1910.

According to family stories, Lynches Tavern at 463 Hudson Street had opened in 1906. This does not seem to be the case, as of yet. It may possible be, however, that it is owned by Thomas Lynch, but is not stating so on this 1910 census.

By any measure, ten people living in a two-story walk up is somewhat extreme. Though it seems, by looking at a picture on google maps, that it also has a basement. I’m not sure how many rooms there are here, but I would guess three, maybe four at the most. Next door is the Donahue family with the Slattery’s and others living at 95 Barrow Street. In two adjacent, very small buildings behind a saloon, there are 26 people living. Imagine this all over Manhattan.

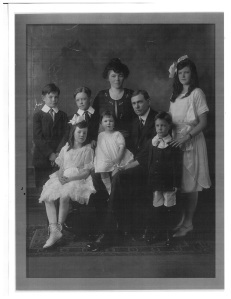

In the Census of New York, 1920 (done on 1/5/1920) We find the Lynch family has moved next door to 463 Hudson Street, just above the saloon that is now called Lynches Tavern. Thomas Lynch (44) now describes his occupation as “Proprietor, Saloon.” This

Thomas Lynch sitting down, Honora behind him with the whole family. This photo was taken right around the 1920 Census of New York.

was very typical of an Irish saloon keeper in New York City at the time, as he is living above the bar.

His family has grown too. He and Honora now have six children, a servant and five boarders/lodgers. Living with Thomas and Honora now are the following:

1) Ellen N. Lynch (11 daughter)

Thomas J. Lynch (9, daughter)

Daniel A. Lynch (7, son)

Mary L. (6, daughter)

James D. (4, son)

Anna M. (1, daughter)

Delian Crawford (20, single servant female), born in Ireland

Harry J. Groh (51, single boarder) Engineer, Iron Foundry, born in New York, both parents from Germany

Michael Lynch (55, widowed lodger) Laborer on the Docks, born in Ireland. Thomas has a younger brother named Michael, but this Michael Lynch is older. So this may be a cousin from Ireland.

William J. Conlen (45, widower lodger) Truck Driver, born in New York

Frederick Thiel (43, married lodger) Laborer, Confectionary, born in Pennsylvania

James Govern (70, widower lodger) laborer on the docks, born in Ireland.

Thomas Roache (55, single lodger) Laborer on the docks, born in Ireland

In the Census of New York, 1930 (done on 4/14/1930) we find the Lynch family has moved to 796 East 19th Street in Brooklyn, which is considered Prospect Park South off Ocean Avenue, a few blocks West of Flatbush Avenue. Thomas Lynch, Head of the household, now describes his work as “Owner, Restaurant.” From all accounts, he is taking the trolleys every morning through Prospect Park north toward the bridges. From there, he has probably been changing trains at the Sands Street Station, which is just north of Downtown Brooklyn, Cadmen Plaza. From there, he is most likely taking the trains across either the Brooklyn Bridge to Park Row, or across the Manhattan Bridge to get to Manhattan. Then, he is taking more the Elevated tracks, such as the Sixth Avenue El, all the way across Manhattan to the West Side, where his saloon is located where he used to live at 463 Hudson Street in Greenwich Village. After work, he takes the same trip, but in reverse.

Living in Brooklyn while working in Manhattan is considered a step above Working Class that the Irish seemed to have been stuck in since The Great Hunger of the 1840s and 1850s. In Thomas’ generation, owning property is very important and at this time in 1930, he wrote on the census that a large “O” to answer the question “Own or Rent.” He then wrote that it was worth a whopping “$17,500.”

Thomas is now 54 years old and Honora (still called “Nora” on the census) is 51 and they have been married for 23 years, which means they would have gotten married most likely in 1907. Their eldest daughter Eleanor (called “Elinore” here) is 22 years old and Thomas (20), their eldest son, is a “Clerk” at a “Brokerage House.”

Daniel A. (18), Mary L. (16), James D. (14) and Anna M. (12) are all in their teens and are all still in school.

A “nephew” has moved in, James Galvin who is the same age as the Lynch’s youngest daughter, Anna at 12. After asking around, a family member explained that young Mr. Galvin “was no blood relative, just a person in need of food and lodging.” So, it turns out that James Galvin is simply the recipient of some good old fashioned Irish hospitality (see ancient Brehon Law).

Finally, at the Lynch home in Brooklyn is a “maid” named Margaret Keane (23, single), who is not in school. Ms. Keane was born in Ireland and arrived in 1923. Her work was described as “Servant” for “Private Family.”

In the Census of New York, 1940 (done on 4/2/1940), we find the Lynch family has moved back to Manhattan and now live at West 16th Street, off 7th Avenue on the West Side. This address, going by google maps again, appears to be a high rise of about 16 floors. There apartment number where they are renting is 19, which would make one believe it is on the first floor. When asked on the census where they lived in 1935, everyone in the home said “Same Place.”

Thomas Lynch now says he is 66 years old. Staying consistent, Honora says she is 61 years old.

The Great Depression hit the Lynch household as hard as everyone else. Thomas now describes his work as “Bartender, Restaurant.” No longer does he say that he is “Owner” of the restaurant at 463 Hudson Street.

The Lynch family was not able to pay the mortgage on the saloon and the bank foreclosed it sometime in the 1935. Thomas was still able to bartend at the longshoreman’s dive, but he was back to paying rent on it to the bank.

However, according to an article in the New York Sun on July 3rd, 1939, John A. King of  the “254 Boulevard Corporation” bought the property back from the North River Savings Bank. John A. King just happened to be the law partner of Thomas Lynch’s son, Daniel A. And from all accounts, the bar was back in the family again.

the “254 Boulevard Corporation” bought the property back from the North River Savings Bank. John A. King just happened to be the law partner of Thomas Lynch’s son, Daniel A. And from all accounts, the bar was back in the family again.

In 1940, only Thomas’ two youngest still live with them, James D. (25) and Anna (21), both single.

Whew, I’m tired. I’m going to take a break. Please get in touch when you can.

Footnotes

~*1 – From the letter sent to me by Dan Lynch () originally from ???? Denis Lynch’s name is said to be “Dennis Spellsey Lynch.

~*2 – If Ellen Cunningham Kelly (who is referred here as “Ellen Lynch”) was born in 1839, Ellen would have been 72 or 73 years of age in 1911, not 74.

The names Bridget and John and their ages do not match up with any names or ages of Ellen Cunningham Kelly’s children, which means then this may be the wrong Lynch family of Clare. No address is offered on this document either.

It is not specified who the mother and father of Mary Louise Clancy are, grandchild of “Ellen Lynch” but, according to a letter that was passed to me, Alice Lynch (b. 1871) married a John Clancy (b. 1861) sometime after 1891 and they had five children, one of which was “Mary (b.1906 in Ireland)” which would make perfect sense here as the child would have been four years old if her birthday was after the date of this census of April 2nd. But Alice Lynch is not living in Ireland at this time, in fact the “Census of New York, 1910” has her living with our Thomas Lynch at 93 Barrow Street, behind Lynches Tavern.

If Ellen Cunningham Kelly and Denis Lynch were married for “52” years, as this census says, they would have been married in the year 1856, since Denis Lynch died in 1908.

November 12, 2013

November Update

So glad you could come by!

I just wanted to take a quick break while we are in the middle of the group of “Irishtown” historical blogs to update a few things about the publication of Light of the Diddicoy come March of next year.

(Also, I provided a quick description for the recent blogs about Brooklyn’s Irishtown. Look for that at the bottom of this blog).

First of all, if you’ve joined in while we’re still this far ahead of publication, I just wanted to thank you from the deepest part of me! Our email list has been growing exponentially and is now over 3,000! If you’d like to join now, there’s a link above called “Join Email List.”

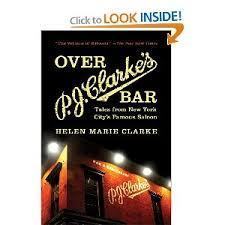

Working closely with Three Rooms Press, Light of the Diddicoy’s publisher and Over the River PR, we are now beginning to set up  readings for March, April and May of next year. Very exciting! We have gotten very positive and encouraging responses from places like the Brooklyn Historical Society, The Irish American Writers & Artists Inc., The Irish Arts Center, Cornelia Street Cafe in Greenwich Village, PJ Clarke’s on the Upper East Side, Guerrilla Lit Series in The Bowery, Dire Reading Series in Cambridge, MA and many, many more. It’s still too early to put up a schedule, but we’ll have one soon.

readings for March, April and May of next year. Very exciting! We have gotten very positive and encouraging responses from places like the Brooklyn Historical Society, The Irish American Writers & Artists Inc., The Irish Arts Center, Cornelia Street Cafe in Greenwich Village, PJ Clarke’s on the Upper East Side, Guerrilla Lit Series in The Bowery, Dire Reading Series in Cambridge, MA and many, many more. It’s still too early to put up a schedule, but we’ll have one soon.

As mentioned previously, Three Rooms Press has really been pushing hard and we’ve received many positive responses about book reviews, come March. I shouldn’t name the websites, periodicals, and persons that have already given excellent feedback, but rest assured Light of the Diddicoy will be covered in many, if not all, of the most prestigious and sought-after reviewers, newspapers, magazines and websites.

Perseus Distributors too have promoted advance review copies and have done an amazing job letting all the major and smaller bookstores around the country and publishing trade magazines know about Light of the Diddicoy. It certainly seems, from the feedback we’re getting, that all the major bookstores are showing interest in a book that combines the history of New York City with Irish and Irish-Americanism and the gangs of the Brooklyn waterfront.

One of the craziest things that has happened lately is the fact that more people in Ireland have “Liked” the Light of the Diddicoy Facebook page than Americans. I have read that the Irish, per capita, read more than any other country, but WOW! It has forced us to consider a great problem for a publisher to have about making distribution in Europe a higher priority.

Light of the Diddicoy also got a facelift recently with its new cover  art! We believe this cover will grab the attention of readers quickly and, going by reactions, it seems everyone agrees.

art! We believe this cover will grab the attention of readers quickly and, going by reactions, it seems everyone agrees.

Light of the Diddicoy was very lucky to have quickly grabbed the attention of Peter Quinn, who has already had incredible successes in the same genre of Historical Fiction. Mr. Quinn’s fascinating book Banished Children of Eve about the “Five Points” section of Manhattan during the 1860s and the subsequent Draft Riots won the American Book Award in 1995. Mr. Quinn said of Light of the Diddicoy

~A rich and rollicking tale of immigrant struggle… Loingsigh’s vision is epic and unflinching.

TJ English is a veteran in the Irish-American New York community. His work over the years provided a springboard for the writing of Light of the Diddicoy.

Recently, Light of the Diddicoy was endorsed by TJ English, the famous author/journalist of Paddy Whacked, The Westies and President of the Irish American Writers & Artists Inc. after he read it, stating:

~Gangsters and dock wallopers along the Brooklyn waterfront intermingle with dirty cops, labor rabble rousers and the unwashed masses of an Irish immigrant class bursting with pluck and vitality… Historical Fiction at its best.

Author Alphie McCourt (A Long Stone’s Throw), a member of the famous Irish/Brooklyn McCourt family (Malachy & Pulitzer Prize-winning Frank McCourt) said of Light of the Diddicoy:

~Eamon Loingsigh is a poet with a pickaxe-and a scalpel attached to the working end. In Light of the Diddicoy, he depicts the Brooklyn Waterfront of the early Twentieth century, and the Irish who controlled it, with hammer-blow prose and spare dialogue.

Quite a few more blurbs are expected as well, so keep your eyes peeled!

If you haven’t opened your eyes to Light of the Diddicoy, or if your friends haven’t heard of it yet, it’s time to find out! Come St. Patrick’s Day, 2014, the journey begins!

Blogs about Irishtown: After three years of research on the White Hand Gang, its members and everything that surrounded them circa 1915/1916, I found that a lot of their actions and quotes to police and newspapers all seemed to center around the past. Many of them had arrived in Brooklyn due to The Great Hunger in Ireland in the 1840s and 1850s. Still very close to their Irish history of fiercely defended communal groups which were separate from the Anglo-American, these boys were still angered at the REASON for their being born in a foreign land. Irishtown, also known as Vinegar Hill, felt itself outside of the Anglo-American law and all of the actions and words of the White Hand Gang members continued this “communality” and “outsider” feeling, even as Irishtown was flooded with Jews and Italians and other immigrants, two bridges connecting their neighborhood to Manhattan were built and the Brooklyn waterfront was built into one of the most densely populated and industrialized collection of neighborhoods in the world by 1915/1916.

In short, these gangsters of the waterfront racket were still fascinated and often referred to their neighborhood as “Old Irishtown.” Spoken with an Irish accent, as does the narrator of the book Liam Garrity and referencing things like “Auld Lang Syne” and the song “Auld Triangle,” the name of the trilogy (Light of the Diddicoy is the first book) is called Auld Irishtown.

These boys and young men existentially fought to keep the honor of their old neighborhood, even as time clicked on and the inevitability of change was taking place.

Check out Code of Silence here, which compares Brooklyn’s Irishtown to Manhattan’s Five Points and The Brooklyn Irish here, which breaks down the number of Irish-born in the 1855 census and beyond.

November 4, 2013

The Brooklyn Irish

Although Irishtown had been known as Brooklyn’s most recognizable, infamous waterfront neighborhood for Irish immigrants in the mid 1800s, it was the city’s long waterfront property that stretched both north and south of Irishtown that was heavily settled by the Famine Irish. In truth, Irishtown could only be seen as the capital amidst the long stretch of Brooklyn waterfront neighborhoods facing the East  River and Manhattan.

River and Manhattan.

By the census year of 1855, the Irish already made up the largest foreign-born group in New York. This constituted a dramatic shift in the ethnic landscape of Brooklyn. In just ten years, the amount of Irish-born inhabitants had jumped from a minimal amount, to 56,753. Out of a total population in Brooklyn of 205,250, its newly arrived Irish-born inhabitants made up about 27.5%.

The impact of such a large amount of immigrants in a short period of time may be difficult to imagine, but it must be remembered that these newly-arrived were not only all from one ethnic background, but they were also terribly destitute, bony from intense starvation, malnourished, disease-ridden, uneducated and untrained people that came from an outdated medieval agrarian community. On top of all of this, at least half of them did not speak English and instead spoke Gaelic and were landing in a culture that was traditionally hostile to their form of religion: Catholicism.

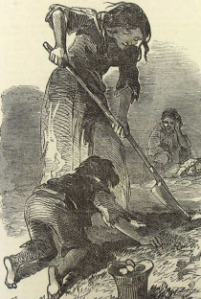

Famous sketch from the 1840s of an Irish mother digging with her children desperately to yield a crop in time to save their lives.

The Great Hunger in Ireland of 1845-1852, or what is commonly, if not erroneously called the “Potato Famine,” caused over 1.5 million (if not more) Irish tenant farmers to flee for lack of food.

“Few newcomers had the resources to go beyond New York and therefore stayed for negative reasons,” said Ronald H. Bayor and Thomas J. Meaghan in their book, The New York Irish. “Most… had no other options… The best capitalized Irish immigrants were those who did not linger in New York, but went elsewhere, making New York and other harbor cities somewhat atypical of the rest of Irish America.”

The waterfront neighborhoods of antebellum Brooklyn was such a place. These neighborhoods of mostly English Protestants and old Dutch aristocracy were quickly overwhelmed by these Catholic “invaders” crippled by diseases, starving and with a legacy of rebelliousness, secrecy, violence and faction fighting within their fiercely communal cooperations. In short, these great numbers of Brooklyn immigrants were in no way interested in assimilating into the incumbent Anglo-Protestant culture.

Since 1825 and the opening of the Erie Canal, Brooklyn had begun to boom as the New York Ports along the Hudson and East Rivers now had access to the great and rising cities in the midwest and beyond.

[image error]

A color drawing from 1855 looking west toward Brooklyn’s Navy Yard. Just beyond it in the area that looks shaded was “Irishtown.” The New York Times described it in an 1866 editorial thusly, “Here homeless and vagabond children, ragged and dirty, wander about.”

Soon, New York become the busiest port city in the world. There was labor work to be had in Brooklyn, in the manufacturing and loading and unloading of goods to be sent around the country and around the world.

Brooklyn was broken down into wards at that time, and although much of the population lived along the waterfront, there were plenty of other neighborhoods inland that were heavily populated by the English and Dutch before the Great Hunger. But the newly arrived Irish immigrants did not go inland, they stayed along the waterfront where the labor and longshoremen jobs were.

One neighborhood in particular gained fame, though it is not as much known today as it was then:

Irishtown.

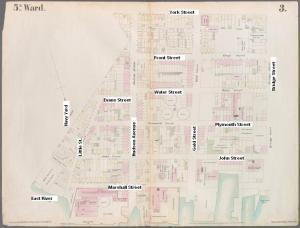

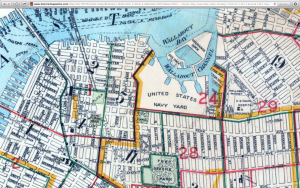

The Fifth Ward from an 1855 Fire Insurance Map, where Brooklyn’s Irishtown is located by the Navy Yard. It was called Vinegar Hill (from the 1798 rebellion in Ireland) even before the Great Hunger.

Located in the old Fifth Ward, Brooklyn’s Irishtown never gained the kind of infamous popularity that Manhattan’s Five Points garnered (as I previously wrote about in Code of Silence), it was nonetheless the center of the immigrant, working class slums and the brawling, closed-off culture of the wild Irish.

Located on one side next to Brooklyn’s Navy Yard that built ships and on the other side with the ferry companies connecting Brooklyn to Manhattan across the East River, Irishtown was centrally located.

Although Irishtown was the face of Brooklyn’s Irish community, it did not even have the distinction of having the most amount of Irish-born (which exclude American born of Irish stock) in it during the 1855 census. The dock and pier neighborhoods of Brooklyn were not just in the Fifth Ward, they were spread from the waterfront in Williamsburg north of Wallabout Bay all the way down to Red Hook and the Gowanus Canal.

During this time, there are three other wards that outnumber Irishtown in total Irish-born of the 1855 census. Cobble Hill, the Fulton Ferry Landing and southeast of the Navy Yard, north of Fort Greene Park. The brownstones of Brooklyn Heights are still considered mansions for the rich Brooklyn landowners at this time, but later will be divided and subdivided for the working class Irish.

The densest area of Irish-born is obviously from the Navy Yard, both inland and on the water to the Fulton Ferry Landing, but surprising numbers existed in the north along the Williamsburg waterfront and south in Cobble Hill, Red Hook and the Gowanus Canal. In fact, 47.7% of the total population of Red Hook in 1855 is Irish-born.

*Census for the State of New York for 1855 (Ward#, area, Irish-born residents)

Ward 1 (Brooklyn Heights 2,227)

Ward 2 (now known as DUMBO 2,967)

Ward 3 (East of Brooklyn Heights 1,964)

Ward 4 (south of DUMBO 2,440)

Ward 5 (Irishtown 5,629)

Ward 6 (Fulton Ferry Landing 6,463)

Ward 7 (Southeast of Navy Yard, north of Fort Greene Park 6,471)

Ward 8 (Gowanus 1,717)

Ward 10 (East of Cobble Hill 6,690)

Ward 11 (West of Ft. Greene Park, south of Irishtown 4,985)

Ward 12 (Red Hook 3,332)

Ward 13 (East of Navy Yard where current Williamsburg Bridge is 2,036)

Ward 14 (North of Williamsburg Bridge along waterfront 4,314)

In these wards, Irish-born constituted 32% of Brooklyn’s total population

In fact it is Brooklyn’s most famous Irish-American toughs, the White Hand Gang that originated not in Irishtown, but in and around Warren Street in Cobble Hill and Red Hook at the beginning of the 20th Century.

So, it is right to assume that masses of Famine Irish landed and settled around the more famous neighborhood of Brooklyn’s Irishtown, but it is the general waterfront area from Williamsburg down to Gowanus, in the pier neighborhoods of the fastest growing port and industrial areas of the city where the majority of them settled. In fact, of the 56,753 Irish-born in Brooklyn in 1855, about 51,000 of them lived in the waterfront neighborhoods.

Long before Ellis Island took in immigrants, Southern Manhattan’s Battery Park did. After disembarking there, many Irish immigrants took the ferry to Brooklyn or moved from the slums of Manhattan to the Brooklyn waterfront for the jobs on the docks and piers there.

And they just kept coming, well after the famine ended. With connections in Brooklyn, Irish-born brought their extended families and friends to New York over the coming years, funding new passages to the city helping keep the Brooklyn working class Irish poor for many years to come.

By 1860, Brooklyn was the largest city in America with 279,122 residents, a large portion of which were either Irish-born or of Irish stock as it is still some years ahead of the considerable amounts of Jewish and Italian immigration to Brooklyn later in the century.

By the census of 1875, the population of Irish-born in Brooklyn jumps to 83,069. In 1880, the U.S. census, which counted both place of birth and parents’ birth place as well, estimated that one-third of all New Yorkers were of Irish parentage. By 1890 as Brooklyn neighborhoods were expanding east and south, the amount of people with Irish stock is at 196,372.

October 18, 2013

Code of Silence

The history of New York City is a very popular topic these days. On Facebook, pages dedicated to old photos have hundreds, sometimes thousands of “Likes.” That was one of the reasons for choosing my topic for the Auld Irishtown trilogy here at artofneed. That along with my own personal interest.

In many cases, very detailed information about neighborhoods can bring on loads of interest. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be posting regular posts about one such neighborhood in Brooklyn: Irishtown. A name that doesn’t even exist any longer. Instead, we know it as its original name: Vinegar Hill. But at one point in time it was loaded with the Irish that were so poor and so destitute that they couldn’t travel any further than the ports that berthed them. Irishtown was such a place, and although Manhattan’s Five Points is more famous, we’ll compare and contrast the two throughout this series, for they had one major difference between them: The Code of Silence that existed in Irishtown. Which is the topic of this first installment. Hope you enjoy:

The Code of Silence

“That alley was the most turbulent spot in Irishtown,” so said a man who called himself the Gas Drip Bard in an 1899 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle about a dangerous place off Gold Street in the mid 1800s. “It would be worth a policeman’s life to enter there after dark, or for that matter in the daylight.”

The old Fifth Ward was where Irishtown was located. In this photo circa 1916, it is right of the Manhattan Bridge, left of the Navy Yard.

Irishtown was located in the old Fifth Ward of Brooklyn. Along the waterfront west of the Navy Yard, east of where the Manhattan Bridge now reaches into the sky. And although it was not as well known as Manhattan’s Five Points of mid 19th Century New York fame, it was equally as notorious and filled to the limit with the same desperate, Famine Irish.

In fact, according to the Census for the State of New York for 1855, in an equally dense area, Irishtown had 5,629 Irish-born among its total population of 16,000. Five Points, according to Tyler Anbinder, Manhattan historian and author of a book on the infamous Five Points, “(had) about 7,200 that were Irish-born” out of a total 14,000 in 1855.

Five Points, known worldwide as the most dangerous neighborhood in New York, was the Miley Cyrus of slums, whereas Irishtown was the JD Salinger of them.

But if Five Points was known far and wide, even internationally for being disease-ridden, filled with prostitution and gambling rings and murderers and gangs… Brooklyn’s Irishtown was known for, well, keeping its secrets.

So desperate were they to keep the law and outsiders away, Irishtown residents took to the rooftops in the early 1870s to hurl streetwise chimney bricks and paving stones at police and federal agents. After many years of attempting to stop the plethora of untaxed, illegal whiskey distilleries in Irishtown, the city was forced to summon the United States Marines through the Navy Yard in an early morning raid in July, 1873.

“A code of silence was observed in Irishtown,” explained New York’s most famous bank robber and Irishtown native Willie Sutton (born 1901) in his biography. “More faithfully than Omerta is observed by the mafia… It wasn’t only the gangs that were at war with the police, everybody was. If a man was arrested, his whole family would run alongside the paddy wagon screaming… All the police ever got out of him was the exercise. Nobody ever talked in Irishtown.”

Here is a photo of what is left of Irishtown/Vinegar Hill. Most of it has been torn down and rebuilt by now, sadly.

These were not rioters in Irishtown, as there were in Five Points ten years earlier during the civil war draft. These were men and women and children that banned together to keep the law out. A commune, almost. But protected violently.

That morning in 1873 has been described in some detail in multiple periodicals of the time. Other articles were written years afterward commemorating what was seen as a symbolic event in Irishtown’s need to keep the police out. When the government is forced to summon the likes of the Marines to put order in a neighborhood, well, that’s pretty remarkable.

For this reason, the code of silence, Irishtown has not received the recognition that Five Points has. There was even a gang that named itself the Five Points Gang (Italian gang of Mulberry Street after the area had been mostly razed). In 2002, an entire movie by Martin Scorcese was based on Five Points.

Like so many Brooklynites have been in the position of doing, Irishtown looked upon the Five Points area with a bit of jealousy, but also with a lowered eye since it seemed everyone over there was out for themselves. To the people of Irishtown, Five Pointers were so selfish that they had no sense of community. Isn’t it the point to keep the coppers out? What it shared in ethnic inhabitants, it contrasted entirely in character.

Many years later in 1923, a gangster in the White Hand Gang named “Wild” Bill Lovett was gunned down on Front Street in Irishtown. Instead of looking to the law for justice, he was quoted as saying, “I got mine. Don’t ask any questions. Don’t try to pump me. It’s give and take. When we get it, we take it and say nothing.”

Not long afterward, another Irish native named Eddie Hughes who was suspected of the original shooting of Lovett, was murdered. But with no witnesses (as usual), no one could be charged.

By that time, of course, refusal to speak with the police was tradition. A tradition in Irishtown that reached back even further in the sensibilities of all those that ended up in Irishtown BECAUSE of law.

A gripping look at a family refusing eviction at the hands of the British police during the famine. A very stirring scenario for most Irish-Americans where the walls were often ripped down and the thatch roof set alight so they couldn’t return.

Back in Ireland in the 1840s, a blight on the staple of the Irish diet, the potato, was used by the British government as a way to remove the tenant farmers from their lands and replace them with a cash crop in cattle. (This argument has gained steam over the years and there are many Irish and Irish-Americans that are dedicated to changing the description of this even from “Famine” to “Genocide,” but let’s stick to the topic here).

The Irish tenant farmer had a tradition of refusing to pay rent. Supported by their secret societies and more interested in their own factions than any foreign occupiers, the Irish were a rebellious lot that made the British colonial landlords boil in anger, due their tenants’ refusal to go along with their laws.

Along came the blight and with a half-hearted and smarmy policy toward it, allowed, often paid for these Irish peasants to be sent in “coffin ships” to places like Brooklyn, New York. At least, those who survived long enough to board the ships. And, those who survived the long journeys.

Over a million died of starvation. Two million more emigrated from a very small island nation. If we were able to go back in time and ask those survivors of the Great Hunger what they felt about law? As it was law, in their eyes, that was manipulated to create such a horrific scenario? Well, what do you think they’d say about it?

Seen here in 1922, Wild Bill Lovett was no believer in the American dream. He wanted to only to be known as the king of his neighborhood and the dock rackets along the heavily industrialized Brooklyn waterfront.

In 1923, Wild Bill Lovett, an Irish American himself, was merely lending his life to the Irish tradition of the code of silence. He was happy to live and die knowing that the police and the Anglo-American laws they enforced had no say in it. Later that same year he did die, in fact, hatcheted in the skull and shot in the neck by, you might’ve guessed it by now, unknown assailants.

Silence was Irishtown’s way of keeping their own traditions. Making their own stories outside of the over-arching Anglo-American culture. The conflicts and the faction fighting in their lives kept within their own borders of Bridge Street and the wall at the Navy Yard.

Like the famous Irish revolutionary Michael Collins said in the movie, “There is one weapon that the British cannot take away from us: we can ignore them.”

Maybe later we’ll talk about Brehon Law, a civil code based on honor that Ireland lived by before the British outlawed it along with the Irish language and, just to make sure they understood who was boss, disallowed anyone perform Catholic Mass anywhere in the isle of Ireland.

Until then, however, look for another post in a few days about Auld Irishtown.

October 10, 2013

PJ Clarke’s

The best way to learn about history is to ask an elder. Sure you can consult the internet or the library, but there is not a more authentic and traditional way than to simply listen and breathe in the story from someone who was there. Especially over a drink or two.

consult the internet or the library, but there is not a more authentic and traditional way than to simply listen and breathe in the story from someone who was there. Especially over a drink or two.

In the book Over P.J. Clarke’s Bar: Tales from New York City’s Famous Saloon by Helen Marie Clarke, you get just that. Written in a conversational tone with an eye for history and the impact on family through the lens, or behind the bar of one of the oldest continuously running bar in New York, Clarke has spun an ancestral yarn on an establishment that has witnessed, within the fray, New York’s history from 1884 to the present.

Mrs. Clarke, who is the grandniece of Patrick “Paddy” Clarke, who took over the saloon in 1912, calmly describes how times changed around the old saloon on 3rd Avenue and 55th Street as if she’s waiting for your Guinness to settle. With the gentle nature of an Irish storyteller, she hands you the ugly truths and the good ol’ times in the same sweet tone.

The saloon originally opened in 1884. Paddy Clarke emigrated from County Leitrim, Ireland in 1902 and eventually saved up enough money (possibly with the help of a beer sponsor) and opened as P.J. Clarke’s in 1912.

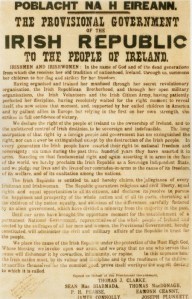

Paddy was a typical Irish immigrant of the era and believed sincerely in Irish freedom back home. He hung photos of Ireland’s dead patriots on his walls alongside Abraham Lincoln in a time when Ireland was still under the thumb of the British Empire. Mrs. Clarke goes on to explain conversations she had with Paddy when she was a child and speaks with a tone of pride how he hung a picture of Ireland’s Proclamation of Independence from the 1916 Easter Rising.

goes on to explain conversations she had with Paddy when she was a child and speaks with a tone of pride how he hung a picture of Ireland’s Proclamation of Independence from the 1916 Easter Rising.

These are the seeds of the traditional New York City Irish pub. The seeds that we so often forget about and the seeds that so many of the young have never heard about. Mrs. Clarke does a great service to describe her grand uncle’s connection to the old country. She also describes how her father and uncles had a very hard time talking about Ireland. Another very important trait of the immigrant Irish as the history of Ireland and its people was seen and felt as the greatest of tragedies. From hundreds of years of oppression, forced emigration and starvation, in her grand uncle’s and her father’s  generation, it was just too emotional to speak of.

generation, it was just too emotional to speak of.

My own great-grandfather owned a similar saloon on Hudson Street in Greenwich Village on the other side of Manhattan. It opened in 1906 and was also a supporter of Irish freedom. So, as Mrs. Clarke reminisces about Paddy’s pride in Irish freedom, it brings this reader back to the stories told in my own childhood of the Irish in New York.

Throughout the history of New York, from two world wars, the Great Depression, the unrest of the 1960s, the city’s recession in the 1970s, PJ Clarke’s stood strong and served up good times.

Richard Harris, one of my favorite actors, once said, “We walked into P.J. Clarke’s, I said, ‘Vinny, my usual.’ And he lined up six double vodkas.”

Famous visitors regularly have come to PJ Clarke’s, from Rocky Marciano, to Jacqueline Kennedy, Richard Harris, Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe to Ernest Borgnine and, according to some recent reading of my own, Malachy McCourt (A Monk Swimming) was a famous drinker at PJ Clarke’s as well.

Today, there is some angst toward the treatment of women in the New York saloons of the old days. And it was true that most women and girls were not allowed inside them. And if they were, they were required to enter through a back entrance. Mrs. Clarke, realizing this treatment, describes the reasons.

“Uncle Paddy’s ‘no women at the bar’ was simply reflective of the culture at the time.”

Since women almost never walked the streets of New York without a male accompanying her, walking into a saloon was just not traditionally acceptable at the time. Mostly because women who did actually patron saloons were prostitutes, as some New York establishments had back rooms and upstairs accommodations for sexual transactions, which the house benefited. In truth, most New Yorkers would have seen a woman sitting in PJ Clarke’s as a “lady of the night.”

But Mrs. Clarke’s tone becomes sorrowful when she mentions that PJ Clarke’s had a policy of ‘no women’ longer than most other New York bars. And in the 1960s, PJ Clarke’s was visited by feminists and protestors that forced it to change.

However, Mrs. Clarke always had access to it from the time she was a young child. Her father and brothers, in New York fashion, lived above the bar with their uncle Paddy for many years.

Through good times and bad, PJ Clarke’s has stood. And oh by the  way, if you happen to be in the city, come by for a drink.

way, if you happen to be in the city, come by for a drink.

It’s still open, 915 Third Avenue.

~Eamon