Eamon Loingsigh's Blog, page 16

January 17, 2015

Sitcom from Purgatory

On January 1st of this year, myself and many others were shocked of news that a British television outlet (Channel 4) is funding a sitcom about the “famine in Ireland.” Hugh  Travers, an Irish writer is behind it and was quoted as describing it as, “���we���re kind of thinking of it as ‘Shameless’ in famine Ireland.��� (Showtime’s ‘Shameless’ chronicles the hilarity involved with��a drunk father of six).

Travers, an Irish writer is behind it and was quoted as describing it as, “���we���re kind of thinking of it as ‘Shameless’ in famine Ireland.��� (Showtime’s ‘Shameless’ chronicles the hilarity involved with��a drunk father of six).

I wasn’t planning on writing about it as I’m deep into the second book in the Auld Irishtown trilogy, but the controversy hasn’t gone away. When I heard the writer behind the Irish show Father Ted, Graham Linehan, was supporting the network’s plans for a sitcom on the famine, I tweeted my opinion to him after he tweeted about “the idiots protesting the famine sitcom.”

@Glinner up with protests of inflammatory actions.

— Eamon Loingsigh (@eamonLoi) January 17, 2015

In response, he tweeted back:

@eamonLoi the writer is Irish, you fuckin moron.

— Graham Linehan (@Glinner) January 17, 2015

For which I tweeted back again:

@Glinner Funded by British television. No ending to an old tradition… gombeens & shoneens. No need for being crude, it's an opinion.

— Eamon Loingsigh (@eamonLoi) January 17, 2015

Not that the world is concerned about my opinion, but I would like to say just a few words. First off, describing this as a sitcom about a “famine” in Ireland is very quickly offending many people. There was a famine on the potato in Ireland, yes, but there was not a famine on food in general in Ireland. In fact, it is extremely well chronicled by award-winning writers all over the world that England, who used Ireland as one of its colonies, exported millions of dollars worth of grain, beeves of cattle, ham, oat, provisions and much, much more during the worst years of what the Irish have come to call The Great Hunger, or An Gorta Mor.

Here is a video of Christy Moore, a famous Irish musician listing off the British exports on the day of September��14, 1847.

It was for this Great Hunger that so many Irish came to port cities like New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Canada, Australia and more. Boney, starved, sick from more than a month-long journey in the worst ships in the British empire by pirates that sought to profit from the catastrophe. They became known as “coffin ships” because so many Irish died in the hulls or, being left on the deck to the elements of the sea, died on the way to America and were dumped overboard. Some ships sunk on the way.��

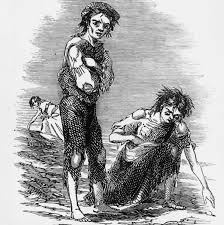

Worse off were those that did not have landlords that paid their passage and were stuck in Ireland. More than a million having died a very slow and horrifying death due to hunger and diseases carried by lice, yellow fever, cholera. To add shame on the shame, many were evicted, often during the winter, left to die on roadsides alone. Children were the most vulnerable and died in the worst poverty Europe had known in centuries. Drawings of women gaunt and crying for their babies. Dying themselves not long afterward. Homeless and despised.

The Acts of Union, forced upon Ireland by the English in 1800 clearly outline that Ireland was part of the��British Empire and therefore responsible for the welfare of its people. But the British mercantilists, closely associated with the English Parliament, strictly believed in the��economic��philosophy of Laissez Faire. Or, abused this “hands off” economic approach to its benefit, many argue. Irish peasants on English lands (within Ireland) were not as profitable as grazing cattle and beef, and so the landlords lobbied against helping the starved and dying.

Those in power also used God against the peasants in Ireland, stating that the famine was a divine intervention, and sited His Providence as a reason the Irish suffered because of their supposed laziness, feckless nature.

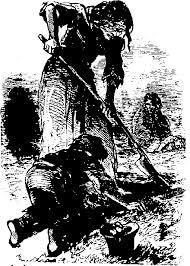

During this time period, the British Parliament made half-hearted attempts to help with schemes such as road building, though many died working on these roads that didn’t pay enough to feed families in any case. Workhouses were supposed to be places to shelter the evicted and starved, but instead came to be places to die in. There were also the soup kitchens, some of which became famous because many of them required the starved and dying to renounce their Catholicism for British Protestantism.

enough to feed families in any case. Workhouses were supposed to be places to shelter the evicted and starved, but instead came to be places to die in. There were also the soup kitchens, some of which became famous because many of them required the starved and dying to renounce their Catholicism for British Protestantism.

During this time period, some of the more well-off Irish took advantage of the situation and gave loans out at exorbitant interest rates. These Irish became known as gombeens and were reviled by the Irish for generations.

These are all true stories. Even the English do not deny they occurred. Cannot deny it. But still to this day, the Great Hunger is mostly ignored and oftentimes made fun of by the English, who long for the heyday of the British Empire. It is, without being divisive or polarizing,��a horrible chapter in world history as reprehensible as the enslaving of Africans or a Holocaust against Jews. And for the Irish (and even some Americans like myself), it is still as inflammatory.

Can you imagine it? A British television outlet funding a COMEDY about the Great Hunger? Wait though, can you imagine a British television outlet funding a comedy about the Great Hunger WRITTEN BY AN IRISHMAN? There could be nothing more inflammatory than going through with this, unless of course Germany planned to fund a comedy about the Holocaust written by a self-hating Jew. Or Americans fund a sitcom about slavery, written by a pandering black man because writing a comedy about the Great Hunger by a gombeen will cause great chaos.

Comedy on Irish famine stifles free speech? No, just bad taste. Like drawing sexpics of others' god, yell fire in a theatre & you get chaos.

— Eamon Loingsigh (@eamonLoi) January 17, 2015

October 31, 2014

Interview: Portraits of Faith

Here is an interview done back in March on location in Brooklyn. The sit-down part of the interview is at Rocky Sullivan’s bar in Red Hook. The poem about Irishtown is read right in front of the gang’s headquarters at 25 Bridge Street, the old “Dock Loaders’ Club.” Other shots are taken on Plymouth Street in DUMBO where the old freight rails are dug into the rough cobblestone streets and in front of the Empire Stores under the bridges. The last shots are at Spoonbill & Sugartown Booksellers in Williamsburg.

I had a great time doing this interview and special thanks goes out to a lot of people in their efforts in getting this together, but Three Rooms Press had a particularly powerful vision and really succeeded here. Terence Donnellan and his film crew were exceptional, as well Kevin Davitt and many more.

Check it out! The Brooklyn Irish in focus via Light of the Diddicoy.

October 21, 2014

A Night of Pete Hamill

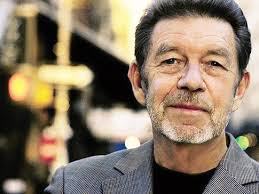

Eugene O’Neill Lifetime Achievement Award winner, Pete Hamill.

I had a great time last night at Irish American Writers & Artists Inc.’s Eugene O’Neill Lifetime Achievement Award.

This year’s honoree is the legendary writer of fiction and New York Post columnist Pete Hamill. The man who defined, with wonderful words, the Brooklyn childhood of my parents and grandparents’ time was honored by many speakers, planned or unplanned.

One of my favorite New York Irish personalities Malachy McCourt said kind things about Mr. Hamill and promptly broke into a Northern Ireland song (where Mr. Hamill’s parents  were born) of Will Ye Go, Lassie, Go?.

were born) of Will Ye Go, Lassie, Go?.

Martin Scorsese autobiographer and famous writer of books like Galway Bay, Mary Pat Kelly came to the stage and honored all the great work of the women in the Irish arts and beyond.

IAW&A president Larry Kirwin, who is also the legendary frontman of the Irish rock/punk band Black ’47 also gave a nice and very typically Irish/NYC speech about how wonderful it is to be a liberal, and how hard it is to be a writer due to the commercialization of the arts.

Governor Andrew Cuomo was a surprise guest-speaker.

Then, out of nowhere came Governor Andrew Cuomo! Governor Cuomo swooped in to say a few words for Pete Hamill who so influenced his thoughts as a young man.

Then! Legendary Irish actor Brian Dennehy came up to the podium and read from Mr. Hamill’s work, causing everyone in the crowd to grab a tissue.

Finally, famous sportswriter Mike Lupica introduced Mr. Hamill with more praising. When Mr. Hamill was finally brought up to the stage, he grabbed the microphone and in typical Irish-NYC black humor, says:

“All these nice words and there’s no corpse in the room?”

Classic night.

For me, I will always remember Pete Hamill’s book The Gift. A young man coming back to Brooklyn after bootcamp with only two wishes, to marry the girl he loves and to be loved by his father. Both ignore him throughout the book, but when his father recognizes and shows love toward the young man, the gift is given sweetly.

Pete Hamill is a man who has defined what it is to be a writer for me. When I received my degree in journalism and wanted to be a novelist and to write about the Irish in New York, I was following Mr. Hamill’s path who was very popular in my Irish-American, New York household.

Thank you to the Irish American Writers and Artists Inc. for a great night of Pete Hamill.

Eamon

October 13, 2014

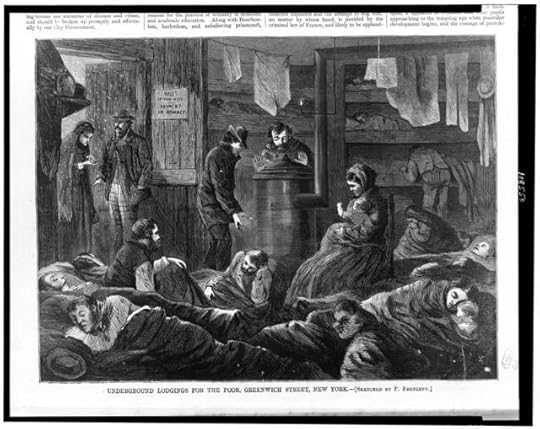

Dependents: Portraits of 50 Irish People in New York Poorhouses, 1861-1865

Really interesting breakdown by historian Damian Shiels of Irish immigrants in New York Poor Houses in the 1860s. Lots of Irish counties and surnames.

Originally posted on Irish in the American Civil War:

Originally posted on Irish in the American Civil War:

On 4th August 1865, an Irish emigrant woman from Cork City gave birth to a baby girl in New York. The child -Mary- had been dealt a tough start to life. Her mother was a pauper, and Mary had entered the world in Richmond County Poor House. Mary’s brother and sister were also paupers, and her mother was described as ‘intemperate’- there were no details regarding her father. Circumstances allowed Mary to be discharged from the Poor House on 12th May 1868, but by 3rd November 1871 she was back in her birthplace. At least she was being given some education, as by 1875 she was able to read. Poor House staff noted that ‘she will soon have to go to service’ and remarked that ‘this child bids fair to be a good servant she is being taught all the requirements of the institution.’

Underground lodgings for the poor of…

View original 4,920 more words

August 5, 2014

Black Tom Explosion, 1916

Most historians directly associate the explosion that occurred on Black Tom’s Island on July 30, 1916 with German saboteurs. Which is accurate, but history has all but erased any connection between this German plot and the Irish Republican movement in the United States, which at the  time was a very powerful lobby. Particularly in New York, New Jersey, Philadelphia and Boston. Also, it seems improbable to this writer that such an undertaking could have been taken without the Irish-dominated dock gangs and longshoremen unions knowing, accepting or benefiting from it.

time was a very powerful lobby. Particularly in New York, New Jersey, Philadelphia and Boston. Also, it seems improbable to this writer that such an undertaking could have been taken without the Irish-dominated dock gangs and longshoremen unions knowing, accepting or benefiting from it.

Most are well aware of Germany’s secret missions of sabotage in the United States during World War I in order to keep the U.S. from entering the war on the side of England. In 1915, Germany attempted to agitate a fight between the U.S. and Mexico and also offered longshoremen unions over $1 million along the East Coast to go on strike, which would succeed in stopping munitions and war supplies from reaching Germany’s enemy, England.

At the time, the International Longshoremen’s Association was headed by an Irishman named T.V. O’Connor, whose second in command was famous Irish-American thug “King Joe” Ryan. These men ruled the longshoremen underworld at the time and certainly had a soft side for Ireland’s freedom from England’s yoke.

“King Joe” Ryan, who became President of the ILA and famous for being the face of longshoremen union racketeering in Malcolm Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize winning reportage in the 1940s. Which then inspired the making of “On the Waterfront” with Marlon Brando.

This brings us to a very popular Irish slogan during World War I: “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s Opportunity.” At the outbreak of the war, Ireland’s Home Rule bill was again put to the side. Still under England’s rule, Irish Republicans were determined to move forward and with England busy at war on the European continent, it was a ripe time for an Irish rebellion. But it couldn’t be done alone and the Irish Republican Brotherhood found its greatest ally in Imperial Germany, which helped them with guns for the Easter Rising of 1916, although Roger Casement’s attempt was scuttled.

In the U.S., the Irish Republican movement was very strong. Particularly in providing money to support Irish freedom and rebellion through Clan na Gael, headed by famous Irish rebel John Devoy.

In saloons across the big U.S. cities, including my great-grandfather’s in Greenwich Village where the docks were only a block away and the Irish longshoremen were known to “pass the hat for Irish freedom,” were many discussions about Ireland. What did the Irish and Irish Americans care if England won World War I? Well, they didn’t. And in fact, Clan na Gael’s influence on the 1916 election was heavy. Irish Americans supported Woodrow Wilson because he promised to keep the U.S. out of World War I and support Ireland’s right to rule its own land. But it was in places like Lynches Tavern at 463 Hudson Street where the three parties all came together: Imperial Germany, Irish-Americans who supported Irish Republicanism and longshoremen.

Although Clan na Gael was investigated by the Directorate of Naval Intelligence and links were found, it was Imperial Germany that has taken the brunt of blame in history for blowing up the munitions storing and warehouses units that caused such an incredibly huge explosion, damaging the Statue of Liberty forever (the torch is still closed to this day because of the Black Tom explosion).

John Devoy in a mug shot in the 1870s while a young man, before being banished to Australia.

To me, it is impossible for something underhanded like this to have occurred without the explicit help or, at the very least, a wink and a nod from both the Irish Republican movement in the U.S. and the longshoremen’s union, which was so heavily populated by the Irish-American working class back then.

For these reasons, a scene in the second book in the Auld Irishtown trilogy, which includes the actual explosion, intimates complicity between the Irish gangs and the unions working in cahoots with Imperial Germany to undermine American shipments of munitions to England during World War I.

July 16, 2014

Auld Irishtown Characters

There are many characters in Light of the Diddicoy and the forthcoming second/third books in the Auld Irishtown trilogy. Within the books, I have purposely attempted to make them as brief, yet distinct as possible. Avoiding confusion is very important to me, yet inevitable with so many different personalities and roles. Therefore, I wanted to keep a list that readers can regularly look at while reading the books. I’ll keep this blog up so it can be referenced. Hopefully it’ll help sort through any confusion.

It’s important to remember that only eight of the fifty-four characters mentioned here are fictional. Liam Garrity, the narrator is the most visible fictional character, others have very small roles such as NY Dock Company’s Silverman, the Gang lawyer Dead Reilly and Liam’s uncle Joseph. All of the remaining characters were real people with real Irish American surnames that mostly retain their original nicknames and monikers, such as The Swede, whose real name was James Finnigan and Cute Charlie Red Donnolly, which is exactly what people used to call him.

I did have to change a couple characters’ names for the simple fact that, back then, so many men’s first names were James, Patrick, Eddie, Frank or John. Bartender Paddy Keenan, for instance, is based on a real life man named Patrick Howlett. James Healy changed to Sean Healy. Frank Seaman changed to Jidge Seaman, “Jidge” being an old way of saying “George.” And in maybe the most dramatic case, a guy who was originally named Frank Madden was changed to Thos Carmody (Thos being short for Thomas). Retaining Frank Madden would only confuse smart readers, who would automatically believe him related to the famous gangster of that time Owney Madden, who he was not related to.

Good luck,

Eamon

Gang Members:

Liam Garrity – Narrator, teenager

Dinny Meehan – White Hand Gang Leader

The Swede – Fighter, Dinny’s protectorate

Vincent Maher – Masher, Dinny’s protectorate

Tommy Tuohey – Irish traveler, Dinny’s protectorate

Lumpy Gilchrist – Numbers guy, Dinny’s accountant

Richie Pegleg Lonergan – Youngster, leader of Lonergan crew

Dockbosses:

Wild Bill Lovett – Red Hook, old Jay Street Gang leader

Cinders Connolly – Jay & Fulton street terminals

Harry the Shiv Reynolds – Atlantic Avenue Terminal

Cute Charlie Red Donnolly – Navy Yard

John Gibney the Lark – Baltic Street Terminal

Other Gang Members:

Big Dick Morissey – Gibney’s righthand, muscle

Philip Large – Connolly’s righthand, Fool-mute

Non Connors – Lovett’s righthand

Darby Leighton – Kicked out of gang, Lovett follower

Pickles Leighton – In Sing Sing, framed by Dinny Meehan in 1913

Paddy Keenan – bartender & Minister of Education

Dance Gillen – Half black, half Irish, King of the Pan Dance

Chisel McGuire – Craps King of Ballyhoo

Needles Ferry – Drug addict

Ragtime Howard – Dock Loaders’ Club stalwart

Dago Tom Montague – Half Italian, half Irish

Frankie Byrne – Lovett follower, old Frankie Byrne Gang leader

Jidge Seaman – Frankie Byrne/Lovett follower

Sean Healy - Frankie Byrne/Lovett follower

Garry Barry – Old Red Onion Gang leader, psychotic

Joey Behan – Older brother of Petey Behan

James Hart – Truck driver

McGowan – Dead, former righthand of Dinny Meehan

Mick Gilligan – Low end follower

Beat McGarry – Old timer, storyteller

Lonergan Crew (teens):

Abe Harms – German Jew, Richie’s righthand

Petey Behan – Thug, feuds with Liam Garrity

Matty Martin – Follower, loves Anna Lonergan

Timothy Quilty – Follower, boxer

Others:

Sadie Meehan – Wife of Dinny Meehan

Tanner Smith – Greenwich Village dockboss, Meehan associate

Rose Leighton – Sadie’s mother

William Brosnan – Poplar Street policeman

Mary Lonergan – Mother of Richie Lonergan

Anna Lonergan – Sister of Richie Lonergan

Frankie Yale – Brooklyn Italian mafia leader

Eugene Wolcott – President NY Dock Co

Silverman – NY Dock Co muscle

King Joe Ryan – ILA leader in NYC

Thos Carmody – ILA recruiter

Joseph Garrity – Liam’s uncle

The Gas Drip Bard – Irishtown storyteller, Old timer

Mr. Lynch – Greenwich Village saloon owner, Hibernian societies.

Dead Reilly – Gang lawyer

Il Maschio – Yale follower

Peter th’ Buck – Northern Ireland refugee

July 8, 2014

July Update

Light of the Diddicoy continues to gain momentum, and so I wanted to take a moment and update everyone on some recent events.

The Irish Voice, an Irish print newspaper in New York City published a very nice piece on Light of the Diddicoy in June. It was recently added to Irish Central‘s website here:

http://www.irishcentral.com/news/irishvoice/The-Irish-in-Brooklyn-then-and-now.html

Amazingly, it sites two books about the Irish in Brooklyn, one of them is Light of the Diddicoy while the other is from the famous Irish writer Colm Toibin and his book, which is currently being filmed in Coney Island named, appropriately, Brooklyn.

“Light of the Diddicoy vividly reminds us of how the Irish shaped Brooklyn and vice versa,” writer Tom Deignan wrote.

“Eamon Loingsigh… just published an excellent, deeply authentic novel of gritty Irish Brooklyn,” the article goes on to say and has many quotes from myself as well.

Also, another popular writer, Andrew Cotto wrote a very positive review here:

“Light of the Diddicoy is an exquisitely-crafted narrative that evokes immense empathy. There are no good characters or bad ones, simply people trying to survive in a place that knows no mercy, a place that is constantly in flux and uninformed by justice. This is a story of how men and women and children survived down under the Manhattan Bridge overpass when no one in Brooklyn or beyond cared about those who lived there.”

Also, I recently hosted an event at McGee’s, an old Manhattan restaurant/bar where we were graced with the presence of more famous authors, such as P eter Quinn (Banished Children of Eve), Malachy McCourt (Amongst Women, I mean A Monk Swimming), Kevin Baker (Paradise Alley), Mary Pat Kelly (Galway Bay) and crime writer Terrence McCaulley.

eter Quinn (Banished Children of Eve), Malachy McCourt (Amongst Women, I mean A Monk Swimming), Kevin Baker (Paradise Alley), Mary Pat Kelly (Galway Bay) and crime writer Terrence McCaulley.

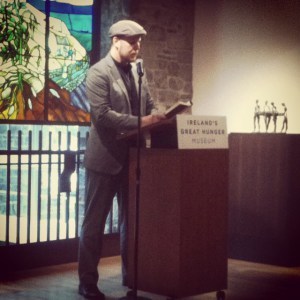

A couple days after that I had a wonderful reading at Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, located at Quinnipiac University, and sold loads of copies too!

Don’t forget to get yours at the link below, where there are 15 more reviews to sift through:

May 21, 2014

Battle: Light and Darkness

Those who know me know that my work is greatly influenced not only by literature, namely the literary Francophile that I admit to being, but also by the films of the 1970s.

A great independence, comparatively speaking, had already set in in Hollywood after its initial onslaught in the 1960s. New and incredible experiments were taking place and I admit that many of them were far-fetched and often fell flat. But what came from these experiments and new freedoms were quite a few absolutely beautiful successes.

initial onslaught in the 1960s. New and incredible experiments were taking place and I admit that many of them were far-fetched and often fell flat. But what came from these experiments and new freedoms were quite a few absolutely beautiful successes.

Maybe my all-time 70s film favorite is Deer Hunter with Apocalypse Now! in a close second. Other movies we can’t forget are ones with strong literary influences like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and A Clockwork Orange, and other streetwise movies like Taxi Driver, Mean Streets, Dog Day Afternoon, The Warriors and movies that appealed to other parts of our anatomy, like Hustler’s Caligula and the Bruce Lee, Woody Allen and the rise of David Lynch movies, not forgetting the beginnings of the modern comedy and horror genres.

At the close of the 1970s we had the beginning of the Spielberg-inspired, corporate formula blockbusters beginning to take center stage, but just before doing so we got the first Mad Max movie in 1979. Although it is not all that well done, I still liked the grimy,  unpolished storyline, especially as a youngster watching these movies in amazement from the floor of my duplex after sneaking up in the middle of the night and catching these classics by accident.

unpolished storyline, especially as a youngster watching these movies in amazement from the floor of my duplex after sneaking up in the middle of the night and catching these classics by accident.

One set of movies that are noticeably absent (although I’m sure many of you have your own favorites) is The Godfather movies Parts 1 and 2. With the passing recently of Gordon Willis, the cinematographer of these and other movies from the era, it made me think of some of the visions of scenes in Light of the Diddicoy as it pertains to the possibility of these books one day reaching the movie theatre or the cable series.

In particular, the flashback scenes of The Godfather Part 2 represents an incredible inspiration for the writing of many of the scenes in Light of the Diddicoy. Albeit, this is a story about the Irish instead of the Italian, and Brooklyn versus Manhattan, the cinematography in these flashback scenes is what often jumped through my mind when creating this ethnic story of the Irish in New York.

Here is the original cover for Light of the Diddicoy, which was scrapped for reasons I never really agreed with. But see the light escaping from the doom here like an impression. I thought the artist, Guy Denning, did really great, not only in showing patience at my surely exasperating requests, but also in capturing that ancient battle between light and darkness.

The title even, Light of the Diddicoy, shows a direct influence of Mr. Willis’ work, as it is the escaping light from the great amount of darkness that pervades the theme of this book, as it was a big theme in the Coppolla/Puzo story shown brilliantly in Willis’ cinematography.

The word “light” in Light of the Diddicoy is that of a candle’s light upon the face of an Irish gypsy in America, and shows the influence upon me of Willis’ work. For while modernity (in the form of electricity) was becoming the acceptable way of lighting homes across New York and America in the early part of the 20th Century, these gypsy-gangsters in Brooklyn symbolically refuse electricity for the candle as a way of showing their refusal to generally accept progress and assimilation.

In the battle between light and darkness, or the escaping of light (hope) from darkness (despair) which pervades all of our lives through any generation, I found Willis to have been the best, most genuine artist to represent it on the big screen.

April 18, 2014

Hope and Gerry Cooney

“Cranford is only four square miles,” Joe’s son said in the kitchen.

I sipped the coffee.

“Everyone kind of knows everyone,” Joe said in his matter-of-fact tone.

Joe and I stepped outside his home and we both smelled the April air, felt the warm wind with only a slight bite left to it.

“It was a long winter,” Joe said. “Never seen it so cold for so long.”

After driving from Florida, I needed to have the car checked since it was running hot the last 400 miles. He drove me across town to hang out at a coffee shop until my car was looked at and offered me two spots “the big coffee chain or the local spot. The big one is new to town. Big news around here.”

“Good choice,” Joe said, then sped off to work after dropping me off.

I could see the cheerful look on the Cranford faces. Freed of hats and scarves and long-collared coats, the men rolled up their sleeves and women wore their favorite shoes again.

One of the five chairs that were set up in a semi-circle were open, so I sat, plugged in the computer and sipped from the wide cup among three 40ish men who were talking animatedly with each other and a lone woman in her early thirties.

After ten minutes of overhearing the men talk about home renovations, local taxes and the current state of the Garden State Parkway, an old man waddled in.

“Hi Hal,” one of the men said.

Hal’s face lit up, “Oh, uh…”

“Michael,” Michael reminded Hal of his name. “Sit here, we were just leaving.”

“Oh uh,” Hal was confused, wanted to say two things at once, yet nothing could be heard accept “uh, oh I’m uh…”

“Don’t worry, Hal,” Michael said. “It’s all you, we were just leaving, right guys?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah.”

And out they went before Hal got a chance to say hello or goodbye.

Sitting next to me, I could smell that Hal carried the musty aroma of a man who didn’t often change his clothes. The perspiration in his shirt and sweatpants from many months of continual use. The scent of the homeless.

“I can’t remember your name,” he said to the woman in the corner chair.

“Janette,” she responded.

“Oh, I’m so sorry,” he said dejectedly. “I can’t seem to remember names anymore. I think it’s the depression, really. It’s just turning me inside out.”

I smiled inside and felt sorry for him at the same time, then peeked at the woman who was cordially grinning, but didn’t respond.

“Janet was it?” Hal asked a few minutes later.

“Janette,” she said simply.

“Oh yeah.”

Through the corner of my eye I could see Hal felt let down that he couldn’t coax Janette into talking with him. He then looked at me deliberately, turned himself in the chair.

“Do I know you?”

“No sir,” I said with a little grin, half cordial, half amused.

“Oh,” he said, looking down.

I went back to my computer.

“Where are you from?” he asked.

“Well, I was born in Long Island, New York but I…”

“I’ve known many people from there,” he interrupted, then stopped himself to ask another question. “Why are you here?”

“Well, I did a reading at the local library last night where…”

“A reading?”

“Yes.”

“Are you a writer?”

“Yes.”

“What do you write?”

“I wrote a book about the Irish in…”

“When I think about the Irish, I think about the potato famine that happened,” he said.

“Yeah, that was a big event,” I agreed, keeping my sentences shorter than I wanted.

“I was an orphan in Jersey City, you know.”

I could hear a slight sigh from Janette, “Oh really?” I asked.

“I was a kicker for USC in college too.”

“Really?”

“Yes, but I only kicked three field goals in two years as a player.”

Two men walked in and one touched Hal on the arm as he was passing by and said hello.

In a delayed reaction, Hal looked to the side but the man was behind him already.

“Who was that?” Hal asked me.

Amused, I shrugged. Janette sat quietly without contribution.

Sitting up in his seat, he attempted to turn his neck but couldn’t quite get it all the way around and eventually quit, awaiting the man’s return.

“I forgot your name again, is it Janice?”

“Janette,” she responded without looking up from her computer.

“Yes, yes.”

“I remember when you were a child, now you’re taller than most men.”

Janette smiled.

Watching a girl walk passed him, he commented, “You know, I don’t like these tights that girls wear today, they’re not becoming.”

“Well, they are called leggings and I’m wearing them now,” Janette said.

“Oh! That’s different.”

She laughed.

“I mean… you look good in them.”

She rolled her eyes and smiled sarcastically, “thanks.”

The two men came back around with to-go cups of coffee when Hal noticed one of them, “John!”

John stopped in the doorway, slowly turned around.

“Was that you that said hello to me?”

“Yeah Hal,” the man said. “My name is James though.”

“Oh, this guy is a writer,” Hal told him, pointing at me.

Unimpressed, the man nodded at me. I nodded back somewhat embarrassed.

“Uh…” Hal thought, turning to me. “What is the name of your book?”

“It’s called…”

“What is your name?” Hal fired another question as James waited in the doorway. “Did I already ask you that?”

“Well I gotta go Hal, good seein’ ya.”

“Oh no,” Hal said. “Well uh… have a good…”

James had walked out the door already.

Hal looked down, then suddenly remembered he had a coffee and turned to grab it with both hands and sipped on it to make sure it wasn’t too hot. Then gulped half of it down. Looking over at me, “Did I ask you your name already?”

“Eamon.”

“Eamon?”

“Yes.”

“I can’t remember names, so I’m sorry… Eamon?”

“Yes.”

“I have this depression and it gets me all… Eamon?”

I smiled and nodded.

“The only thing I ever think about, with this depression is… death,” he announced with both hands in the air.

I didn’t say anything, but wanted to.

“I used to be able to run. I was a great athlete, I played football for USC, you know. It happened when I turned 80. I couldn’t run anymore.”

“Did you hurt your knee or have a surgery or something?” I asked.

“What? No, I just couldn’t run anymore. It hurt too much. Before that, I ran everyday until I just couldn’t.”

I thought about the terror of having the ability to do something for eighty years, then quickly losing it from one day to the next.

“Aaron?”

“Eamon.”

“I’m sorry, did you say something about… What do you do?”

“I’m a writer.”

“Oh yeah, yeah… What do you write? Books?”

“Yes,” I handed him a copy of my current book.

“Wow,” Hal said holding it in his hand. “This is amazing.”

I smiled at the thought of someone still thinking it a great accomplishment to write a book.

“I can’t even read anymore,” Hal said squinting at the words. “How much does it cost?”

“Oh, well it retails at sixteen dollars.”

“Oh,” he looked down dejectedly, then said under his breath. “I bet Gerry Cooney would love this book.”

“Gerry Cooney? The boxer?”

“Yes, nobody never said a bad word about the man. Gentlest man you’ve ever met,” Hal explained to me with the book in his left hand, eyes ablaze in wonder. “I talk to him quite a bit. He calls me on my birthday every year.”

I nodded an impressed nod.

“He’s from Long Island too you know, but he lives around here now… And he’s Irish too… Boy he had a left hook.”

“Yeah,” I agreed.

“He had Holmes on the run,” he assured me. “I remember it to this day. Cooney got knocked down once, I think it was the third, but after that Cooney was all over him. The belt was coming home, we all shouted. It was the time of my life, that fight was. Never forget it. Gone to history, but I’ll never forget it.”

A minute later and I pulled the video of the fight up on my computer and showed him.

“Oh my God!” Hal guffawed. “How did you do that?”

Janette snickered.

Watching the video, I said, “at least he got the chance.”

Hal then looked at me seriously, “Have you ever seen the move On the Waterfront?”

Janette sighed.

“I have.”

“Listen,” Hal said, putting my book down on the table and clearing his throat. “‘It wasn’t him, Cha’ley, it was you. Rememba that night in the Garden you came down to my dressing room and ya said, ‘Kid, this ain’t your night. We’re going for the price on Wilson.’ You rememba that? ‘This ain’t your night’! My night! I coulda taken Wilson apart! So what happens? He gets the title shot outdoors on the ballpark and what do I get? A one-way ticket to Palooka-ville! You was my brotha, Cha’ley, you shoulda looked out for me a little bit. You shoulda taken care of me just a little bit so I wouldn’t have to take them dives for the short-end money… Oh I had some bets down for you. You saw some money…. You don’t understand. I coulda had class. I coulda been a contenda. I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am, let’s face it. It was you, Charley.’”

I smiled all the way through the dialogue and in the middle of the local coffee shop, I applauded Hal when he finished. Janette tried as best she could to keep her eyes on the computer and the baristas and patrons gave simple, polite smiles.

“Now that was amazing, Hal,” I said. “Spot on.”

“Andy?”

“Eamon.”

“Eamon, yes,” he said, fixing himself in his chair. “Can you look me up on that thing?”

“The computer? Sure, what’s your last name?”

“Kitchna, Hal Kitchna. That’s not my real name, you know. I was an orphan in Jersey City, but look up me up, I was a player at USC on the football team.”

I did a search and quickly found his name mentioned in a book covering the 1959 USC game versus Notre Dame where in the third quarter, Hal Kitchna converted an extra point. I showed him.

“Wow, I’m in a book?”

“You sure are.”

“You know, if I had a better childhood, I coulda been somebody. I was lucky to get in at USC, you know. Everyone was smarter than me though. Well, not really smarter, because I was very smart, but, I don’t know, raised better, I guess. Nothing can replace a mother’s love.”

“I think you turned out just fine, Hal,” I said.

“I’m going to get somebody here to buy your book for me, then I’m going to give it to Gerry Cooney,” Hal said, and before I could laugh or remark, he turned to a man that walked in the door. “Jeff Deerfield, come here.”

The man seemed surprised, “This guy is an author.”

Jeff Deerfield smiled and kept walking.

“Don Smith,” Hal said to the next man walking in. “He’s an author, he has a book.”

Don Smith congratulated me, and walked on.

Meanwhile, my phone rang. It was the mechanic working on my car. My attention was pulled away from Hal. The car was finished and ready for me, so I then called Joe, who said he’d be over in twenty minutes or so to take me to the auto repair shop.

“Here he is, here he is,” Hal said pointing at me.

A short man stood in front of me but did not shake my hand, “You’re the author?”

I smiled, “Yes.”

“You write about the Irish?”

“Yes.”

“I went to Ireland once,” Hal seemed happy sitting next to me as the man spoke. “It was the best trip I ever took. The people there are so nice. I went to the Guinness Brewery also. You know, it tastes better there then anywhere else in the world, because that’s where they make it.”

“Yes, they do.”

“Okay, I gotta go,” the man said.

“Steve,” Hal said. “Do you want to buy his book?”

“Goodbye,” Steve said smiling as he backed his way out the door.

Hal put his hand on his forehead and looked as though he might cry. “It’s time for me to catch my bus now,” he said downcast.

“My ride is on the way too,” I said.

We shared a quiet moment together as Janette had entirely blocked us out by now.

“Everyone deserves a chance,” Hal mumbled under his breath.

A few minutes later and we were both waiting outside in the April sun on the curb. I hadn’t realized how bad his legs were until we walked out the door together. Hal shuffled and apologized. He told me again about his depression and how he used to be able to run.

“The only thing I ever think about is death,” he said.

“All we really need is hope in this life, I think,” said I.

“It really is.”

“I want you to have this, Hal,” I handed him my book.

“But I can’t pay for it.”

“It’s a present from me, can you give it to Gerry Cooney?”

“He’ll love it!” Hal said. “He knows a lot of people, you know. Everyone loves Gerry Cooney, nobody never said a bad word about the man. Do you believe me, that I’ll get it to him?”

“I know you will.”

April 8, 2014

Richie “Pegleg” Lonergan

Note: Richie “Pegleg” Lonergan is a character in the historical novel Light of the Diddicoy. Get your copy here.

Brooklyn, 1925 – On Christmas night just south of the Gowanus Canal at 154 20th Street, the bodies of three young men were found at a ramshackle saloon known as The Adonis Social Club. One of them had been dragged outside, evidenced by the long blood streaks on the sidewalk, and left in the gutter.

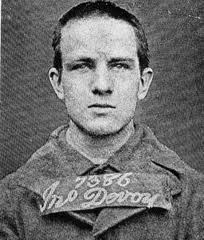

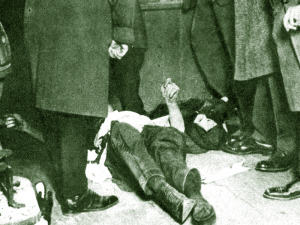

Mugshot of Richard Lonergan

The three young men were well known Irish gangsters from the northern part of the Brooklyn waterfront up toward the bridges. It took an Irish detective from the Poplar Street Station (located at the abutment to the Brooklyn Bridge) to identify them. They were Aaron “Abe” Harms, Cornelius “Needles” Ferry and twenty four year-old Richard “Pegleg” Lonergan, leader of Irishtown’s old White Hand Gang. Lonergan, the newspapers reported, still had a “fresh toothpick” lodged in the corner of his mouth.

James Hart, another Whitehander, was found at the Cumberland Street Hospital not far from the Adonis Social Club with a gunshot wound to the leg. Per Det. Brosnan’s request, two other Irish gangsters were arrested for questioning and said to have been at the Italian club during the shooting. They were Patrick “Happy” Maloney and Joseph “Ragtime” Howard.

A “hat check girl,” a female “entertainer” and another female guest were taken into custody also. Although all three had noticeable Irish surnames, they were working at the Adonis Social Club at the time, or were a guest. The only Italians arrested that were at the scene of the triple murder were the following, Sylvester Agoglia, bartender Anthony Desso and one Alphonse Capone.

Al Capone, arrested for the murder of three White Hand members.

Rumors had it that the Whitehanders, led by Lonergan, commented to the girls to “come back with white men, for chrissake.” One can only wonder if it was the girls that brought the Irish gangsters to the Italian neighborhood, but one thing was for sure, since the death of former leader Dinny Meehan in 1920, then of “Wild Bill” Lovett in 1923, the White Hand Gang was loosing territory to the Italians. Lonergan, it’s been said, wanted a final stand off to the death.

At the Lonergan wake on Dec. 30, which was held at the tenement where the Lonergans lived on Johnson Street, two other members of the White Hand Gang were arrested for threatening reporters not to take pictures. They were Matthew “Matty” Martin and Frank Gervasio.

Eventually Capone was let go by police for lack of witnesses (even though the bar was full, no shots were heard. Even by the upstairs residents). But it was this event that brought full circle what started seven years earlier when a young Capone was forced from his hometown of Brooklyn in 1918 to Chicago because, as the famous Irishtown native Willie Sutton said, “the Irish mob played too rough.”

Richard Lonergan was born into royal gang blood. His mother was Mary Brady, most likely the sister of Lower East Side Irish gang leader Yake Brady (or Yakey Yake Brady). Mary married John Lonergan, who was a failed bare-knuckle prize fighter and mid-level tough for the Yake Brady Gang. Together, they had 15 children. They might have had more, if Mary hadn’t murdered John after he punched their daughter Anna in the face one day in 1922.

Anna was known as the “Queen of the Irishtown Docks.” By all accounts, she was beautiful and was quickly courted by none other than William “Wild Bill” Lovett, who had gained a strong reputation after killing Dinny Meehan and a few others. The

William “Wild Bill” Lovett

Lovetts and the Lonergans were family friends before both families moved to Brooklyn from the Lower East Side.

When Richie (his family called him “Richie,” not Pegleg), was eight years old, his mother Mary sent him for a loaf of bread, so the story goes. Along the way, the boy was run over by a trolley which severed his leg at the knee. Soon enough, Richie had his own gang of young teenagers and after Lovett decided to join his Jay Street Gang with Dinny Meehan’s White Hand Gang umbrella organization, Lonergan soon followed suit.

Richie quickly gained a reputation as a brisk fist fighter, wooden leg or not. He was arrested a number of times for fighting and drinking and at one point, while working at his bicycle shop, killed an Italian boy who was attempting to force Richie to sell drugs out of it. Richie was arrested, but soon let go for the usual reason: no witnesses.

It was right around this time that Al Capone’s wife, Mary “Mae” Coughlin (an Irish girl) gave birth to their son, Sonny. Capone was by this time considered the future of Italian organized crime. As a safety precaution, since the White Hand Gang was regularly threatening to kill him, Johnny Torrio and Frankie Yale decided to send Scarface Al to Chicago. Not only because big money was available there, but it was safer as he was not as well-known among the wild Irish like he was in Brooklyn. So, it was the White Hand Gang that forced Al Capone out of Brooklyn. But as we know, he gets his revenge.

After Meehan was murdered in 1920, a war for the seat of power within the White Hand Gang broke out. Lovett fled to Chicago, leaving Richie temporarily in charge of the gang. Over a period of eight months, close to 15 bodies were found of the followers of Lovett/Lonergan and the followers of the dead Meehan.

After Lovett came back, Richie naturally stood aside for his elder’s experience, but in 1923, Lovett quit the gang for suburban life with Anna Lonergan, moving to New Jersey. Eventually Lovett was murdered that same year, and the gang was in Lonergan’s hands.

Lovett, dead on the floor on a Bridge Street saloon.

Although Richie was now the leader, the White Hand Gang was a shell of its former self. Many things had changed and it was the Italian groups that had best organized the rumrunning and illegal importation of liquor during Prohibition that weakened the old Irish grip on power along the docks of Brooklyn. The Italians thought big, while Richie and the Irishers still had a street-by-street mentality. From the Navy Yard down to Red Hook, the gang still ran the tribute racket of longshoremen, but the Albany lawmakers and the googoo Protestants who believed in Progressivism were changing the way politics treated the poor, giving them more opportunities instead of ignoring them altogether (which strengthened the street gang lifestyle).

The White Hand Gang was in disarray and many within it still didn’t see Richie as the true leader. This disorganization was used and encouraged by the Italians. Richie, a known alcoholic, was angered at the declining state of the gang he had been a member of since he was only 15 years old. Now 24 and the leader, he wanted a final showdown.

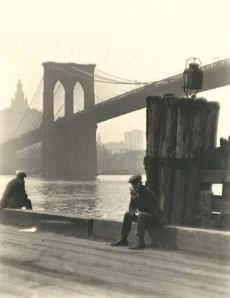

The piers under the Brooklyn Bridge.

Speculatively, when Richie “Pegleg” Lonergan learned about the three Irish girls working at the Italian place that Al Capone was going to be in, Richie gathered five or six of his men, made sure they were armed, and headed for death at the Adonis Social Club.

Al Capone, as we know, went back to Chicago after his son’s surgery in Brooklyn and made it into the history books. Richie Lonergan into Cavalry Cemetery.

In the historical novel Light of the Diddicoy, Richie Lonergan is a 15 year old who is courted by gang leader Dinny Meehan. Meehan uses the fact that Lovett, Richie’s childhood friend, has already submitted to give tribute to his gang and offers to help the Lonergan family open a bicycle shop. The young Lonergan refuses, then leaves.

On the way out of the saloon at the White Hand Gang’s headquarters, one of Dinny’s dock bosses pokes fun at the teenage  Lonergan, who stops and stares the man down, then challenges him to a fight. The man weighs sixty pounds more than the kid, but Richie is not concerned. Within minutes, the entire gang surrounds the two in the ancient fighter’s circle and places bets on who they think will win, and this is how Richie “Pegleg” Lonergan joined the White Hand Gang.

Lonergan, who stops and stares the man down, then challenges him to a fight. The man weighs sixty pounds more than the kid, but Richie is not concerned. Within minutes, the entire gang surrounds the two in the ancient fighter’s circle and places bets on who they think will win, and this is how Richie “Pegleg” Lonergan joined the White Hand Gang.

Go get your copy here.