Brian Clegg's Blog, page 93

July 3, 2014

Half getting Spotify

Some related artists, earlierI can't justify paying £10 a month for Spotify, the music streaming service, but I have dabbled with the free version, and now that it is possible, for instance, to specify that you want to play the tracks of a specific album in the mobile version (even if it has to be shuffled), I am finally starting to get the point of Spotify. Of course, it's useless for all my 70s concept prog rock albums, which have to be played in the correct track order, or Rick Wakeman comes round and duffs you up. But for a lot of others, shuffle is just fine.

Some related artists, earlierI can't justify paying £10 a month for Spotify, the music streaming service, but I have dabbled with the free version, and now that it is possible, for instance, to specify that you want to play the tracks of a specific album in the mobile version (even if it has to be shuffled), I am finally starting to get the point of Spotify. Of course, it's useless for all my 70s concept prog rock albums, which have to be played in the correct track order, or Rick Wakeman comes round and duffs you up. But for a lot of others, shuffle is just fine.However I do still have a bit of a problem with the streaming service (over and above the feeble royalty payments they make to the performers). The thing is, when I want music at the moment I typically go to my iTunes library and flick through it and I'm looking at stuff I know and love - I can browse it sensibly. But Spotify is too big to browse in an undirected fashion.

I find myself staring at the interface thinking 'I can play almost anything. What should I choose?' And I don't know where to start. If you go into Browse, it really doesn't help. I know I can, for instance, go into Pink Floyd and choose 'Related Artists'... and use that kind of mechanism to navigate through stuff I might like... but even so, it's hard work.

So much though I find the concept appealing, I think I'm still mostly stuck in old fogy iTunes land.

Published on July 03, 2014 00:55

July 1, 2014

Get started on your book!

I'd like to draw your attention to the 'Writing a popular science book' Masterclass organised by the Guardian on 20 July in London.

I'd like to draw your attention to the 'Writing a popular science book' Masterclass organised by the Guardian on 20 July in London.Whether you are a scientist who would like to get wider public interest in your field, or just someone who has always wanted to write a book, this is a great opportunity to gain the necessary know-how on everything from choosing topics to selling your idea and the publishing process.

With talks from scientist and communicator Professor Stephen Curry, TV presenter and author Angela Saini, former science book publisher and author Simon Flynn, award winning science writer Brian Clegg and former biologist and author M G Harris, plus the opportunity to pitch your book ideas to an expert panel for instant feedback, it should be a brilliant day. To ensure a place, tickets need to be booked by 7 July - you can find all the details on the Guardian website.

Here's a little more about the team:

Brian Clegg is a popular science writer with 20 books in print who has written for publications from the Observer to Playboy. After degrees in Natural Sciences and Operational Research, he worked at British Airways before leaving to set up a company giving training in business creativity. These days, most of his time is taken up writing popular science books and giving talks. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. Find out more on Brian's website.

Angela Saini is a British science journalist and author, whose first book Geek Nation: How Indian Science is Taking Over the World was published in 2011. Angela has also been published in Science, Wired, the Guardian and New Scientist and is a frequent presenter on BBC radio, for shows including Material World and More or Less. In 2008, she carried out an investigation into bogus universities which was broadcast on the BBC TV's flagship Ten O'Clock News.

Simon Flynn has degrees in chemistry and philosophy and worked for a good number of years in publishing, becoming managing director of leading UK independent publisher Icon Books. He recently left the publishing world to become a science teacher.

MG Harris is the author of the popular Joshua Files series of novels. Born in Mexico and brought up in Manchester, she studied biochemistry at St Catherine's College, Oxford University, before pursuing a doctorate at St Cross College, Oxford. MG spent several years working in research laboratories before setting up her own internet company. She is a successful young adult fiction author and will bring to the panel a mix of expertise in biology and in the narrative style so important for good popular science. In an attempt to cover up the fact that at heart she's a bit of a geek, MG spends as much time as possible going out to salsa clubs to dance.

Stephen Curry is a Professor of Structural Biology at Imperial College. His main research interests are in structural analysis — using X-ray crystallography— of the molecular basis of replication RNA viruses such as foot-and-mouth disease virus and noroviruses (which include the infamous 'winter vomiting bug'). Since 2008 Curry has written regularly about his research and the scientific life past and present on his Reciprocal Space blog and at the Guardian, Curry is also a founder member and vice-chair of Science is Vital, a UK group that campaigns on scientific issues, and is on the board of directors of the Campaign for Science and Engineering.

Published on July 01, 2014 04:26

Now that's what I call a graph

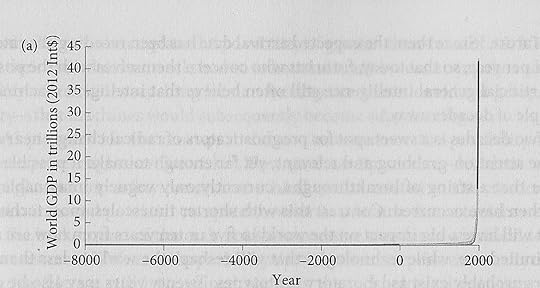

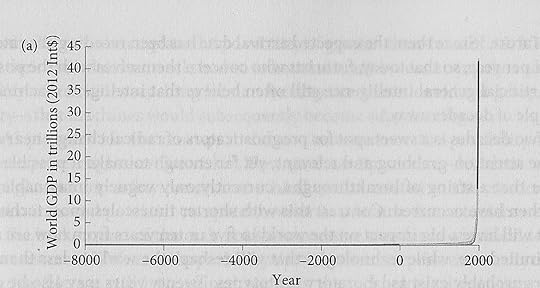

Reading for review Superintelligence by Nick Bostrom, I couldn't help but be struck by this graph:

The remarkable thing is, if you zoom in, a huge amount of that growth has happened in my lifetime. We talk casually of change, but I think this emphasises how different things are now from the way they have been at any time in history.

And as for the famous climate change 'hockey stick' graph - 'Call that a hockey stick? THIS is a hockey stick!' (HT to Crocodile Dundee.)

The remarkable thing is, if you zoom in, a huge amount of that growth has happened in my lifetime. We talk casually of change, but I think this emphasises how different things are now from the way they have been at any time in history.

And as for the famous climate change 'hockey stick' graph - 'Call that a hockey stick? THIS is a hockey stick!' (HT to Crocodile Dundee.)

Published on July 01, 2014 01:14

June 30, 2014

Sexism is symmetrical

There has been some mention in the press in the UK recently about a council receiving complaints because builders were wolf-whistling at women as they went past a building site. This is has provoked a whole spectrum of responses from 'It's just a bit of fun'/'It makes you [the woman] feel good' to 'It is objectification'/'It makes you feel threatened.'

There has been some mention in the press in the UK recently about a council receiving complaints because builders were wolf-whistling at women as they went past a building site. This is has provoked a whole spectrum of responses from 'It's just a bit of fun'/'It makes you [the woman] feel good' to 'It is objectification'/'It makes you feel threatened.'I personally think that it should be discouraged, as I feel sexism has no place in modern society, whatever the excuse, and this seems to be suggesting there are circumstances where take a sexist attitude doesn't really matter. We wouldn't accept casual racism because it's 'just a bit of fun'.

But equally, I am genuinely very uncomfortable about the casual sexism in the Diet Coke adverts that we have been subjected to, apparently for 30 years. I've included one of the latest at the bottom of the page. I honestly think if the same advert was done with a bunch of men ogling a woman and encouraging her to take her top off there would be a huge outcry. Why aren't the anti-sexists complaining about this too? A touch of dual standards?

In the end, our approach to sexism has to be symmetrical, or we become hypocrites.

Published on June 30, 2014 01:30

June 27, 2014

Software could be cleverer - but only if software designers think like people

Here's what happens if you type a properly formatted phone number

Here's what happens if you type a properly formatted phone numberinto many a web form. The error message in red appears.In my dim distant past I did quite a lot of work on the design of the user interface between people and computers - how you interact with a computer (or these days, often, the web) - and it shocks me how stupid most software still is.

When I first programmed computers professionally I soon started exploring ways to make the interaction more friendly. My earliest work pre-dated graphic user interface. The user had to type commands into a console. And, surprise surprise, people made mistakes. So I put in a little routine to capture when errors occurred to see what they were typing wrong and then modified the software so it would cope with the most obvious mistakes. This isn't rocket science. Computers are much better at sorting out basic errors than people are, as long as they are pointed in the right direction.

Let me give you two examples.

In the UK phone numbers have always traditionally been written as two or three blocks. So, for instance, a Swindon number might be 01793 123456, while a central London number could be written as 020 7123 4567 (or more sensibly 0207 123 4567). Very often, websites ask you to type in a number. And surprisingly often what will happen if you type in a number like this is that the site responds, as above, with a warning that you have got the format wrong - because it didn't want spaces. In the example above, taken from an ITV website, they even go to the trouble of telling you not to use spaces (someone should tell them Not To Use Capitals in the middle of a sentence) - but this totally misses the point. That instruction is unnecessary, because people should be able to use spaces - and the fact they've had to include the warning shows that lots of people do.

Any C programmer will tell you that this is a brainless mistake on the part of the programmer, because there is a routine in the C language, which in various variants underlies much modern programming, that takes spaces out of string of text. The programmer doesn't even have to write something themselves - they can just whap the input through this routine, and their software will never even know that there was a space. But no, instead, they program it to complain and force the user to retype it. This is doubly irritating if, like me, you have your computer to set up to automatically fill in information like phone numbers in web forms, which the Apple software properly does with the space in place.

Here's another example. A full web URL is something like http://www.brianclegg.net Note what comes after the 'http' - a colon. Now a colon is a fiddly thing to type, as it's a shifted character. So I bet over the years many people have typed http;//www.brianclegg.net instead, with a semicolon after the http. And guess what? It doesn't work. Again, it's a trivial exercise for your software that reads an address to substitute colon for semicolon. (I know you don't usually have to type http://, but there are some circumstances when you do.)

Admittedly this kind of automatic correction isn't always appropriate. You can't always guess what someone meant. But if, as in the first example, the person typed the number correctly and you are just forcing a particular format, or, as in the second example, there is no sensible alternative interpretation, it's much more polite and efficient to do the right thing and make your software take the kind of imaginative leap that people do all the time without thinking about it.

Published on June 27, 2014 02:24

June 26, 2014

Not lateral thinking, boring thinking

One of those pictures that people pass around via Facebook has appeared on my screen several times:

Apparently we are supposed to be impressed with the lateral thinking skills of the young Chinese children who worked out that the space the car is in is labelled 87 (upside down).

But I think the people who are circulating this totally miss the point of lateral thinking. That was the obvious answer, but almost all real world problems (as opposed to school tests) have multiple solutions, so there certainly should not be a single 'right' answer.

For example, perfectly acceptable solutions include that the space is labelled:Park hereVisitor's SpaceHeadmaster0 (Indicating this is non-allocated parking)42 (Because it's the answer)... and I am sure you can think of more.

To be fair to those setting the test, the original did have the question 'What parking spot # is the car parked in?' which was omitted in the way it was distributed on Facebook, which makes it less of a lateral thinking problem. But also a lot more boring.

Apparently we are supposed to be impressed with the lateral thinking skills of the young Chinese children who worked out that the space the car is in is labelled 87 (upside down).

But I think the people who are circulating this totally miss the point of lateral thinking. That was the obvious answer, but almost all real world problems (as opposed to school tests) have multiple solutions, so there certainly should not be a single 'right' answer.

For example, perfectly acceptable solutions include that the space is labelled:Park hereVisitor's SpaceHeadmaster0 (Indicating this is non-allocated parking)42 (Because it's the answer)... and I am sure you can think of more.

To be fair to those setting the test, the original did have the question 'What parking spot # is the car parked in?' which was omitted in the way it was distributed on Facebook, which makes it less of a lateral thinking problem. But also a lot more boring.

Published on June 26, 2014 00:30

June 25, 2014

Stars are useful

Personally, I think stars are underrated. Not the ones in the sky - if it weren't for one of them, the Sun, the Earth wouldn't exist (and even if there was an Earth, there would be no life on it because it would be far too cold). For that matter, if it weren't for stars in general there would be no atoms other than hydrogen, helium and a touch of lithium - making the whole concept of a planet (or a person) inconceivable. So the stars of the cosmos are seriously rated.

Personally, I think stars are underrated. Not the ones in the sky - if it weren't for one of them, the Sun, the Earth wouldn't exist (and even if there was an Earth, there would be no life on it because it would be far too cold). For that matter, if it weren't for stars in general there would be no atoms other than hydrogen, helium and a touch of lithium - making the whole concept of a planet (or a person) inconceivable. So the stars of the cosmos are seriously rated.Nor am I talking about the stars of stage and screen. Because, let's face it, most of them are seriously overrated. I refer instead to the habit of awarding stars in reviews.

A good while ago I wrote to the journal Nature, complaining about some of the book reviews that they carried. I pointed out that the (long) reviews said nothing whatsoever about the book itself and whether it was any good - which is what the potential reader wants - instead, the review merely gave the reviewer a chance to do his or her potted version of the theme of the book. They said what the book was about, but not if it was any good or whether you should read it. I got what was, frankly, a rather snotty email back from someone at Nature saying something to the effect of 'ours aren't the trivial sort of reviews you have on www.popularscience.co.uk. We aren't going to start giving a book stars like you do.'

Personally, I think this is a mistake. Life is too short to read every review - it's very handy to be able to check out the star rating and then decide which reviews to read. I'm not suggesting we only take notice of the star rating, but it's a good indicator of whether the reviewer considers a book (or film or whatever) really bad or excellent - in both cases suggesting the review is worth getting into in more depth. Assuming, of course, the review does give you a judgement on the book, as theirs failed to do.

However a star rating means different things to different people, so I thought it would be useful to finish by giving a quick guide to the way we use the star rating system on www.popularscience.co.uk:

* - Just doesn't work for us. If you think like us, avoid it

** - Has some interesting points, but probably only for a limited audience

*** - Good solid book, well worth reading if you are interested in the topic

**** - Excellent book that any popular science fan would want to read

***** - One of the best popular science books of the year

ImageCredit: NASA, ESA, and J. Maiz Apellaniz (Instituto de Astrofisica de Andalucia, Spain)

Published on June 25, 2014 00:26

June 24, 2014

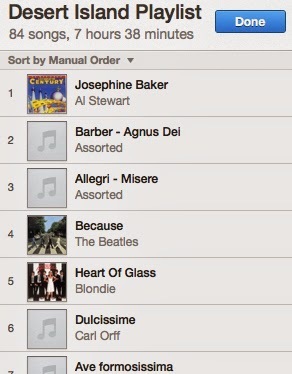

Desert Island Playlist

The radio programme

Desert Island Discs

goes from strength to strength, but if I'm honest, it's a bit dated. If you don't know it, guests on this Radio 4 show list the 10 records they would take with them on a desert island (plus various biographical bits).

The radio programme

Desert Island Discs

goes from strength to strength, but if I'm honest, it's a bit dated. If you don't know it, guests on this Radio 4 show list the 10 records they would take with them on a desert island (plus various biographical bits).It's all very well, but we really wouldn't like to be so limited, would we? So I've devised a new version - Desert Island Playlist. The rules are simple. Construct a playlist of your favourite music. You can have as many tracks as you like, but you are only allowed one track per band/artist or one piece per classical composers. What would yours be like?

I've listed mine below, and for those who like techno things, I've embedded a Spotify version of most of the playlist here so you can listen to them:

So here we go. I warn you, it's quite long. The order is simply the order I came across the tracks on iTunes, so it's in 'no particular order', as they say:

Al Stewart - Josephine Baker - a hard choice to get just one from my favourite singer/song writer, but this is one of my least-known favouritesBarber - Agnus Dei - I first came across this as background music in an animated section of a video game and fell in love with itAllegri - Miserere - simply stunningBeatles - Because - Abbey Road was an amazing album for me. It was the first pop record I really got into and coincided with one of those formative holidays where you meet girls and thingsBlondie - Heart of Glass - had to be something from Parallel LinesOrff - Carmina Burana - Dulcissime/Ave formosissima/O Fortuna - the final three tracks of this remarkable piece where the heroine gives her all, we celebrate love... and the wheel of fortune turns and nothing has changed. Forget the X-Factor associations, this is powerful stuffCarpenters - We've Only Just Begun - sobVaughan Williams - Bushes and Briars - I could have had one his lush orchestral pieces, but this male voice harmony setting of a folk song that I used to sing with my old chapel choir is electricWills - By the Waters of Babylon - I don't know if this has ever been recorded apart from the hissy recording I have of Selwyn chapel choir, but I think it's gorgeousLeighton - Drop, Drop Slow Tears - another obscure 20th century composer, but more scrumptious dark choral workTavener - The Lamb - sweetS. S. Wesley - Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis in B flat - the definitive Edwardian version of these miniature choral masterpiecesCurved Air - Puppets - one of many greats on the Second Album of this remarkable bandBeethoven - Moonlight Sonata - so I'm an old romanticDavid Bowie - Life on Mars - wowDire Straits - Money for Nothing - the background music to a trip to New OrleansDon McLean - Vincent - in memory of a student concert, where someone sang this and blew everyone awayThe Eagles - Journey of the Sorcerer - could have done Hotel California, but let's celebrate HHGTTGEd Sheeran - The A Team - a kids' influence, but I like itFleetwood Mac - Oh Daddy - could really have been anything from this albumGenesis - I Know What I Like - just love the 'lawnmower' bitMahler - Symphony 5 - one of the jollier works from my favourite symphonic composerHowells - Like as the Hart - possibly the best British 20th century church music composer. HauntingJethro Tull - Ring Out, Solstice Bells - unique sound and funJudie Tzuke - For you - could just listen to this over and over. Beautifully craftedKarl Jenkins - Benedictus - played too much by Classic FM, but still goodKate Bush - Lionheart - I know she says her first 3 albums were too studio dominated, but I prefer them to her later workKing Crimson - The Court of the Crimson King - nothing to addTallis - If Ye Love Me - a perfect short anthem from this early English masterKirsty MacColl - What Do Pretty Girls Do - again, difficult to pin down a definitive song, so a pretty random choiceLindsey Stirling - Shatter Me - my latest discovery. Love itLily Allen - The Fear - perfect song for her generationManhattan Transfer - A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square - shiver-sendingly goodMike Oldfield - Tubular Bells - despite meaning we see Richard Branson on those excruciating ads, wonderfully originalPearsall - Lay a Garland - it's a fake tudorbethan piece from the master of Victorian revival, but no less beautiful for thatPink Floyd - Welcome to the Machine - who made that stupid 'one track' rule? But from probably their most perfect albumThe Police - Don't Stand So Close to Me - I hated the Police initially as someone on the floor above played 'Message in a Bottle' repeatedly, but got to like them - and the menace in this one is impressivePurcell - Dido and Aeneas, When I am Laid in Earth - the most moving aria from the only opera worth listening to end to endBach - Well Tempered Clavier Prelude and Fugue in C major - perfection from the masterSheppard - Dum transisset Sabbatum - to modern ears, the tudorbethan Sheppard breaks all the musical rules, but does so remarkablySimon and Garfunkel - Homeward Bound - I could have chosen 20 at least. The soundtrack of my university yearsSting - Moon over Bourbon Street - I've seen it (the moon over Bourbon Street, I mean), and despite everything wrong with Sting, this song is so evocativeStravinsky - The Firebird - the complete ballet, not the suite. Orchestral perfection throughout.Supertramp - Crime of the Century - in my youth I did a lot of travelling by train for the fun of it, and the Paddington station announcements on this track take me right backSwingle - The Oxen - gorgeous setting of this Thomas Hardy poemTom Lehrer - I Hold Your Hand in Mine - my party piece if I'm asked to singToyah - I Want to be Free - one of her two hits, not really my favourites, but the rest (and yes, I have a lot of Toyah albums, someone has to) are an acquired tasteVan der Graaf Generator - Mask - gut-wrenching stuffOldham - Remember O Thou Man - cracking choral music from this one-hit wonderByrd - Mass for Four Voices - musical perfection from the greatest ever English composerYes - See All Good People - not subtle, but still brilliant10cc - Brand New Day - I could have chosen practically any track of their two key albumsDerek and the Dominos - Layla - what's not to love?Monteverdi - Magnificat - the musical equivalent of a high gothic building like King's chapel in CambridgeThe Who - I'm Free - I'd be hated by Who purists, but I prefer the movie version to the original album of TommyPhew!

UPDATED - In case you don't bother to read comments, M. G. Harris bullied me below into whittling it down to the 10 I would have under traditional Desert Island Discs rules. It's a struggle, but these would be my 10:

1. Al Stewart - Josephine Baker

2. Barber - Agnus Dei

3. Vaughan Williams - Bushes and Briars

4. Pearsall - Lay a Garland

5. Pink Floyd - Welcome to the Machine

6. Simon and Garfunkel - Homeward Bound

7. Sting - Moon over Bourbon Street

8. Stravinsky - The Firebird - the complete ballet, not the suite.

9. Supertramp - Crime of the Century

10. Byrd - Mass for Four Voices

Published on June 24, 2014 00:30

June 23, 2014

Hair dye takes on the fuel crisis?

I have always been highly dubious of hydrogen fuelled cars. Okay, they're nice and eco-green because their only waste product is water. But hydrogen takes up three times as much volume as petrol for the same energy output, there is no hydrogen infrastructure, and (as the Hindenburg demonstrated) you don't want a problem at a filling station with leaking hydrogen. I would much rather we put more effort into battery technology, getting them more energy dense, and making them faster to re-charge.

I have always been highly dubious of hydrogen fuelled cars. Okay, they're nice and eco-green because their only waste product is water. But hydrogen takes up three times as much volume as petrol for the same energy output, there is no hydrogen infrastructure, and (as the Hindenburg demonstrated) you don't want a problem at a filling station with leaking hydrogen. I would much rather we put more effort into battery technology, getting them more energy dense, and making them faster to re-charge.However I would hate to be considered closed-minded, so I share the STFC's latest idea - instead of hydrogen, use ammonia. Although ammonia itself isn't a fuel, you can 'crack' it to give off nitrogen and hydrogen, which is then used in the usual manner in a fuel cell. Or you can use it as a fuel directly with a bit of hydrogen (see below), though despite the airy hand-waving, I would point out that those NOx gasses they hope they can get rid of are worse greenhouse gasses than CO2.

I still have some issues with this. It's quite a complex process from fuel to energy out because you have to go through a chemical reaction along the way. And I don't know what the energy density of ammonia is (any suggestions?) - and there is still an infrastructure problem, though providing ammonia in filling stations is more on a par with LPG, rather than the harsher conditions of hydrogen supply. So not a whole hearted 'Whey-hey, we've solved it!', but at least a 'Hmm, there might be something in it.'

Take a look at the excitable press release:

UK researchers today announced what they believe to be a game changer in the use of hydrogen as a “green” fuel. A new discovery by scientists at the UK’s Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), offers a viable solution to the challenges of storage and cost by using ammonia as a clean and secure hydrogen-containing energy source to produce hydrogen on-demand in situ.

When the components of ammonia are separated (a technique known as cracking) they form one part nitrogen and three parts hydrogen. Many catalysts can effectively crack ammonia to release the hydrogen, but the best ones are very expensive precious metals. This new method is different and involves two simultaneous chemical processes rather than using a catalyst, and can achieve the same result at a fraction of the cost.

Ammonia can be stored on-board in vehicles at low pressures in conformable plastic tanks. Meanwhile on the forecourts, the infrastructure technology for ammonia is as straightforward as that for liquid petroleum gas (LPG).Professor Bill David, who led the STFC research team at the ISIS Neutron Source, said “Our approach is as effective as the best current catalysts but the active material, sodium amide, costs pennies to produce. We can produce hydrogen from ammonia ‘on demand’ effectively and affordably.

“Few people think of ammonia as a fuel but we believe that it is the natural alternative to fossil fuels. For cars, we don’t even need to go to the complications of a fuel-cell vehicle. A small amount of hydrogen mixed with ammonia is sufficient to provide combustion in a conventional car engine. While our process is not yet optimised, we estimate that an ammonia decomposition reactor no bigger than a 2-litre bottle will provide enough hydrogen to run a mid-range family car.”

“We’ve even thought about how we can make ammonia as safe as possible and stop the release of NOx gases,” added Professor David. “This fundamental science therefore has immense potential to change the use of hydrogen as a fuel."

Ammonia is already one of the most transported bulk chemicals worldwide. It is ammonia that is the feedstock for the fertilisers that enable the production of almost half the world’s food. Increasing ammonia production is technologically straightforward and there is no obvious reason why this existing infrastructure cannot be extended so that ammonia not only feeds but powers the planet.

Speaking about this new development from the team at STFC, Professor David MacKay FRS, Chief Scientific Advisor at the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) said “We believe that there is no single solution to the challenges we face in decarbonising the fuel chain, but this research suggests that ammonia based technologies are worth further consideration and may well play an important part in the future energy landscape. “

Five years ago, Professor Steven Chu, Nobel Prize winner and, at that time, the US Secretary of State for Energy in the Obama administration, sounded a death knell for the hydrogen economy with his statement that, while it takes only three miracles to be declared a saint, it would take four miracles to achieve a hydrogen-based energy economy. This work from STFC researchers could well be a turning point.

Kate Ronayne, Head of Innovation at STFC said: “This exciting research has the potential to dramatically influence the static and mobile energy solutions of the future. While still at an early stage, this innovative work offers a very elegant solution to some of the major challenges in harnessing the power of hydrogen as a fuel source.”

This has been a Green Heretic production

Published on June 23, 2014 00:36

June 20, 2014

What's that smell?

As soon as a chemist hears the word 'pyridine' there's a natural tendency to hold his or her nose. Its odour has been described as the stink of ‘an unventilated room, full of the infirm and dying'.

As soon as a chemist hears the word 'pyridine' there's a natural tendency to hold his or her nose. Its odour has been described as the stink of ‘an unventilated room, full of the infirm and dying'.But there is more to this simple aromatic compound - including a refined nineteenth century battle over who discovered its structure - as you will discover in my latest Royal Society of Chemistry podcast.

To find out more about pyridine, take a listen by clicking play on the bar at the top of the page - or if that doesn't work for you, pop over to its page on the RSC site.

Published on June 20, 2014 02:40