Brian Clegg's Blog, page 82

December 30, 2014

The sad fate of the bound proof

Some have boring covers, others look like the

Some have boring covers, others look like thereal thing, but there's usually a clue...What do you call a book that's not a book? A bound proof (or if you are American and like a good acronym, an ARC, standing for Advanced Reading/Reader Copy).

It sort of makes sense. While I, as a reader, would always prefer to read a finished copy of a book, the publisher likes to get reviews in as early as possible, particularly if the reviewer is likely to provide snappy remarks to put on the cover. So quite often, before the book is actually produced, they will typeset and bind as a paperback the uncorrected proofs and send them out to eager reviewers.

The reviewer reads this not-quite-a-book as usual and produces his or her words of wisdom. But what to do next?

With a real book I have two choices. If I love it, I put it on the shelf for future re-reading. But shelf space is very limited and I can only do this with 2 or 3 books a year, where I review about 50. The rest, I'm afraid, I resell. Some people mutter about a free copy being sold, but short of putting it in the recycling, whatever I do will result in that free copy going on the market. And bearing in mind I don't get paid for the reviews I do for www.popularscience.co.uk, I don't think this is an unreasonable thing to do. (It's not just me. One of my favourite bits of Brian Aldiss's excellent autobiography, Bury My Heart at W. H. Smith is his description of John Betjeman regularly coming into the bookshop Aldiss worked in with a pile of review books to sell on.)

However, with a bound proof I am faced with much more of a quandary. I don't really want to keep it, even if it is a great book, because it's not the real thing and doesn't look good on the shelf. And I can't sell it or even give it away. So they really do end up in the recycling. And that feels awfully sad.

Published on December 30, 2014 02:38

December 29, 2014

A Scandi too far?

Pronounced?..In the old days, foreign product names were anglicised where necessary, to avoid undue confusion in the British populace. But gradually, over time, as we've got more sophisticated, we have been exposed to more of the real thing without our brains exploding. So, for instance, despite much moaning, the brand we always called 'nessuls' as in 'Nestles Milky Bar', sneakily switched to being 'nesslay' as a better approximation to Nestlé.

Pronounced?..In the old days, foreign product names were anglicised where necessary, to avoid undue confusion in the British populace. But gradually, over time, as we've got more sophisticated, we have been exposed to more of the real thing without our brains exploding. So, for instance, despite much moaning, the brand we always called 'nessuls' as in 'Nestles Milky Bar', sneakily switched to being 'nesslay' as a better approximation to Nestlé.Now, perhaps thinking that we have been prepared for the exotic by our fondness for The Killing and The Bridge, that household standard Ikea has made the risky switch from 'eye-kee-uh' to 'ick-ay-ah', presumably also closer to the original pronunciation. As far as I can tell, the Great British Public (GBP) has yet to adopt this. People still sigh and gird their loins at thought of facing the industrial-strength unfriendliness of the car park of a Eyekeeuh store. But perhaps we will end up with something like the puzzling hybrid used by the more educated driver in an attempt to pronounce the name of the car manufacturer also known as VW. I suspect the initials will always remain 'vee double-you' rather than 'fow vey' as I suppose they should be, but where some of the GBP goes for the full English 'vokes-waggon' many adopt 'vokes-vargen' as a halfway house to 'folks-vargen'.

I don't know why, but my suspicion is that there is a limit. Chances are that yummy mummies will continue to take their kiddywinks on the school run in a 'volvo' rather than a 'wolwo', because, frankly, in English it sounds rather silly.

But who can tell...

Published on December 29, 2014 01:36

December 24, 2014

Happy Christmas!

I'd just like to wish everyone a Happy Christmas and a great New Year. Posting here is likely to be suspended for the next week - see you in 2015.

I'd just like to wish everyone a Happy Christmas and a great New Year. Posting here is likely to be suspended for the next week - see you in 2015.As a bit of passing entertainment, here's a Christmas Medley, arranged by the excellent Roger Witney and sung by the best group I've sung in, Nonessence.

Published on December 24, 2014 03:17

December 19, 2014

Have Rough Guides missed the point?

I was interested to see that the Rough Guides folk have declared that Birmingham is one of the

I was interested to see that the Rough Guides folk have declared that Birmingham is one of the There is, however, from my viewpoint, one strange piece of parochialism in the Rough Guides choice. Because one of Birmingham's selling points was its vast cultural diversity in restaurants and the like. Now, for me, this is certainly a plus for domestic visitors, but a turn-off for the world market. When I go out for a meal on home turf, I love the option to sample food from around the world. But when I go abroad, it's the last thing that I want.

Do the Rough Guide people go to Paris and hunt out a pizza? Do they eat cassoulet in Athens and McDonalds in Bangalore? When you go abroad you want to sample the local food.

Now at this point thirty years ago, you would be right in wheeling out the old 'but British food is rubbish' argument. Not any more. There is plenty of great British food these days, from superb fish dishes to magnificent pies. (Not to mention snail porridge, or whatever Heston gets up to.) It was interesting that on the TV show about Liberty, when Chinese visitors came they didn't want to see Liberty's magnificent oriental carpets, or its designer wear from around the world. They wanted to see Burberry. People visit another country for what's uniquely from that country, not for what's available everywhere else in the world too. So next time, Rough Guides, don't be so parochial.

Published on December 19, 2014 01:38

December 18, 2014

The sadness of 5 minutes of fame

That #1 album (currently #3,529 on Amazon)No, I don't refer to my own 5 minutes of fame, though it is the anniversary of my taking part in 'celebrity' University Challenge, but that of Swindon's attempt at the X-Factor crown in 2012, Jahméne (or Jasmine, as the spellchecker would prefer it). Now, for all I know he is now revelling in the success of his '#1 Album' (that's what his website says, so it must be true), but I must admit he didn't look all that happy when I saw him this Monday.

That #1 album (currently #3,529 on Amazon)No, I don't refer to my own 5 minutes of fame, though it is the anniversary of my taking part in 'celebrity' University Challenge, but that of Swindon's attempt at the X-Factor crown in 2012, Jahméne (or Jasmine, as the spellchecker would prefer it). Now, for all I know he is now revelling in the success of his '#1 Album' (that's what his website says, so it must be true), but I must admit he didn't look all that happy when I saw him this Monday.I was walking through our local Asda, where Mr Douglas used to work before his TV exposure. All I spotted to begin with was a posse of Asda staff heading in my direction, accompanied by a couple of photographers. Somewhere in the centre of the bunch was a smartly dressed young man who I assumed was a management trainee. Even after I walked straight past him about six inches away, I didn't cotton on - it's only as I was doing the self-service checkout thing and looked back that I spotted what was occurring.

Once it did fall in place, I couldn't help think he really did look like he'd rather be anywhere else. On the show, when he returned to his place of work with the TV cameras in tow it was all smiles and happiness, but it was clear that Monday's appearance was a piece of publicity work that Jahméne really didn't want to do. And I can kind of understand that. If he really does have a '#1 album', why does he still have to do this kind of thing? Of course they had to pull the 'humble background' card on X-Factor because it's a hugely manipulative show and that's what it's all about. But once he is established, shouldn't it be the music that makes the statement, without the need for this stuff? I have no idea what Adele did before she was a singer - and why should I care?

Whether or not Jahméne is doing well - and I genuinely hope he is - I couldn't help be amused by an aside from one nearby Asda worker to another as we watched Jahméne being photographed seated at an Asda checkout. 'He never worked on a checkout,' she hissed. Such is the price of fame.

If it's your kind of thing, check out JD's album on Amazon.

Published on December 18, 2014 02:11

December 17, 2014

Of poetry and railways

If you were a railway enthusiast you would know why finding this

If you were a railway enthusiast you would know why finding thison the front of your train would be exciting...Despite having several friends who are poets (and very nice people they are too), I really don't get poetry. At least, I didn't until last Friday, when the light dawned during a village Christmas shindig.

There was a pre-Christmas evening of merrymaking in a nearby village hall, and with a number of others I had been asked to come along and help support the carol singing that would intersperse the important bits of drinking, eating, nattering and more drinking. What I, and quite a lot of the audience, didn't realise is that there were also going to be poems. Three poets, apparently connected to Swindon's successful Festival of Poetry came along to give renditions of their own and others' work.

I could help but observe the strange atmosphere in the hall during the poetry readings. It was, to be honest, a bit uncomfortable. People stared into space or at candles or generally looked as they had probably not looked since the English class at school many years before. And then it all changed. One of the poets read a funny poem. In an Irish accent. (Because he was Irish. A secondary observation is that poetry always sounds better in an Irish accent than in a UK one.) The audience came alive. They suddenly wanted to have eye contact with the reader. They smiled. They looked at each other. It was a different event altogether.

... but this wouldn't.

... but this wouldn't. (At least not as exciting. But better than being in a DMU.)

And that's when the parallel between poetry lovers and railway enthusiasts struck me. I have some form in this respect. I was a railway enthusiast in my teens. In case you are thinking 'trainspotter,' it's not the same thing. I was indeed a trainspotter up to about the age of 13, but this was replaced by a sheer enthusiasm for trains and travelling by train, to the extent that, at age 15, with two other friends, I bought a week's 'railrover' ticket given access to all of Britain's railways. And we spent the week on the trains, only leaving the railway network four times during the period. (Our biggest excursion was to Land's End, for which we had to get a bus. Oh, the indignity.)

Now there was a clear gap between what we railway enthusiasts thought about trains, and what ordinary folk did. Ordinary folk could indeed enjoy a special case, like going on the Orient Express, or being pulled by a preserved steam locomotive. But they would never have understood why there was a difference between being pulled out of Paddington behind the stylish lines of a Western diesel hydraulic, and the lowest of the low, a diesel multiple unit. They would never have understood the visceral thrill of standing by a window up the front of a train on the East Coast Main Line, hearing - no, feeling - the roar of a Deltic in full flight.

And so it is with poetry. Most of us are steam train enjoyers and Orient Express dabblers when it comes to poetry, where steam trains are the rhythmic engaging classics like The Night Mail (yes, trains again) and the Orient Expresses of poetry are the funny ones. It is only the relative few, mostly I suspect poets themselves, who are really engaged by the wider concept. I found it interesting that our Irish poetry host kept saying that a poet he was introducing was 'Well respected in the poetry community', or 'known among the poetry fraternity' or some such remark. They too, like the railway enthusiasts, are a cadre, a group with a common interest not shared by the rest of us. And that's absolutely fine.

However, what it does mean, poets please note, is that you shouldn't be disappointed when we get all excited by Roger McGough and Benjamin Zephaniah but fail to engage with your beautifully crafted stanzas on the plight of a mistle thrush that has lost an eye and can't, Janus-like, see the dawning new year from the ashes of the old.* We just can't all be railway enthusiasts either. Life is sad like that.

* If you have written such a poem, apologies - I was just picking random, poet-like feelings out of the ether.

Published on December 17, 2014 01:00

December 16, 2014

What is light, REALLY?

Every now and then someone sends me an interesting question about science, and, while I can't guarantee to answer it, I do my best. I got one yesterday that said 'if light can be considered traveling in packets, what is between those packets? Does anything exist (in the space) at the end of one photon and the beginning of the next photon?' And this a particularly engaging question, not so much for the answer, which is pretty straightforward, but for the implications it has for the way we talk about physics.

Every now and then someone sends me an interesting question about science, and, while I can't guarantee to answer it, I do my best. I got one yesterday that said 'if light can be considered traveling in packets, what is between those packets? Does anything exist (in the space) at the end of one photon and the beginning of the next photon?' And this a particularly engaging question, not so much for the answer, which is pretty straightforward, but for the implications it has for the way we talk about physics.The answer, to get it out of the way, is nothing. There is nothing (in terms of the light itself) in between photons or between the 'end of one photon and the beginning of the next' - apart from anything else, photons don't really have 'ends'. A beam of light can be described as a set of discontinuous particles we call photons and there is no more something between them, linking them, than there is amongst a stream of electrons. Yet that's where the story gets interesting.

Part of the problem, I think, is that word 'packet'. We tend to use it when talking about the early development of quantum theory as it reflects the terminology used at the time. But it does give a highly misleading impression that a photon is a traveling 'packet' of light waves, rather than a particle like an electron. It's true that, before measurement a quantum particle doesn't have a location, but is instead a spread out probability wave describing the chances of finding it in any particular place, but that is in no sense a wave in the same sense that classically we would have imagined a beam of light as a set of continuous actual waves in the ether, nor does it make a photon a spread-out wave packet.

The other thing that is misleading is that eminent scientists tend to say things about light and other quantum phenomena that arguably isn't really what they mean, but is said at a kind of meta-level that they take to mean one thing, but the world can interpret rather too literally.

A classic example was Richard Feynman's comment about light in his book QED. He said:

I want to emphasize that light comes in this form – particles. It is very important to know that light behaves like particles, especially for those of you who have gone to school, where you were probably told something about light behaving like waves. I’m telling you the way it does behave – like particles.Before I comment on that, let me give you a quote from another Nobel Prize winning physicist, Steven Weinberg who wrote (about ten years before Feynman's book came out):

[T]he inhabitants of the universe [are] conceived to be a set of fields – an electron field, a proton field, an electromagnetic field – and particles [are] reduced to mere epiphenomena.It would seem that each was telling us what light (encompassed in Weinberg's more general remark) is . But they weren't. Each was making a point, emphasising that a conception of light familiar to their audience wasn't the only way of looking at. Feynman was saying 'you've been told light is a wave, but I can explain all its behaviour using (very special) particles.' Weinberg was saying 'particles aren't really necessary, you can describe what's going on just using fields.' But I don't think Feynman believed that light is a stream of particles, or that Weinberg believes that light is a variation in a field.

Here's the really gut-wrenching thing. We can't know the truth about light. We don't know what it 'really' is and we never will. We just have various models of light that can be useful to predict its behaviour. For basic use - say for producing everyday optics - the old classical idea of a continuous wave propagating through space works fine, and it's simple to use. Once we introduce quantum effects, and the interaction between light and matter, Feynman's elegant diagrams and a particle model work well (bearing in mind these are peculiar particles with phase and a tendency to take every possible path between origin and destination, not bullet-like, straight line particles). And for most modern physics, a field approach is most effective.

However, none of these - not waves, not quantum particles, not quantum fields - is what light is . They are all models, ways we use to build a toy version of reality and see how well it reflects the real thing. Light is light. It does what light does. Those models help us predict what light will do. And that's the limit of science. It is immensely valuable. It allows to make all sorts of interesting hypotheses derived from those models, and to develop all sorts of wonderful technology. But it is not the 'truth' about reality, a clear window on the workings of the universe. As St Paul put it, we see through a glass darkly (i.e. as they saw things in the poor mirrors of the day). As humans we are all model builders, making mental constructs to get a handle on the world around us, but scientists do this in a particularly precise, beautiful and robust way. Something to celebrate indeed. But don't expect them to have superhuman powers.

You can find out more about this fun quantum stuff - and the way it has been used to make remarkable technology - in my book The Quantum Age .

Published on December 16, 2014 01:21

December 15, 2014

Joly Monsters

I've come across two very different versions of Dom Joly. One is the pleasant family guy I've seen in Cirencester's best coffee shop. The other is the 'TV personality' who has appeared in the kind of excruciatingly unfunny shows that I wouldn't watch with a barge pole. (This is not quite a mixed metaphor if you use Decartes' model of light.) Luckily, Scary Monsters and Super Creeps was written by the former Joly.

I've come across two very different versions of Dom Joly. One is the pleasant family guy I've seen in Cirencester's best coffee shop. The other is the 'TV personality' who has appeared in the kind of excruciatingly unfunny shows that I wouldn't watch with a barge pole. (This is not quite a mixed metaphor if you use Decartes' model of light.) Luckily, Scary Monsters and Super Creeps was written by the former Joly.Although ostensibly about hunting down famous monsters from bigfoot to the ogopogo, it is probably best read as a humorous travel book, one of my favourite genre, and the reason I bought it. There are some wonderful writers in this genre - think, for instance, Bill Bryson, Dave Gorman and Stuart Maconie. In fact, for me, the humorous travel book is far better than the serious kind.

In principle, Scary Monsters ticks all the boxes. We've got a funny, self-deprecating narrator and interesting locations to visit. Not only do we get Loch Ness, but we also get to see the likes of Japan and the Republic of Congo through Joly's eyes. Like all good travel stories, some of his adventures are fraught with problems, and a couple of near-death experiences. What can possibly go wrong?

It's really hard to put your finger on what is wrong with this book - but there is something. It's not Joly or his writing. It's not the places he visits or the people he meets. I think, in the end, it's the theme that doesn't work. Although the frameworks that some humorous travel books are hung on are pretty flimsy (I'm talking to you, Dave Gorman - not to mention that other guy who went round Ireland with a fridge), at least they have the potential to be fulfilled. Going to see mythical monsters inevitably lacks a satisfactory conclusion.

It probably doesn't help that Joly's monster hunting technique is essential to turn up at the alleged location and mooch around. A problem that is reinforced when, in at least one situation, the travel problems he faces are so big that he never even makes it to the monster's home. Along the way he meets lots of people who, when asked 'Have you seen the monster?' say 'No, I haven't, but I know lots of people who have.' And like their secondhand stories, this book lacks the narrative drive to pull the reader in for long sections.

It really isn't a bad book, and worth taking a look if you are interested in cryptozoology (if only to see how not to do it) or like pretty well anything from the humorous travel shelf.

You can find out more or buy it at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Published on December 15, 2014 01:07

December 11, 2014

Science fiction weapons can be strangely mundane

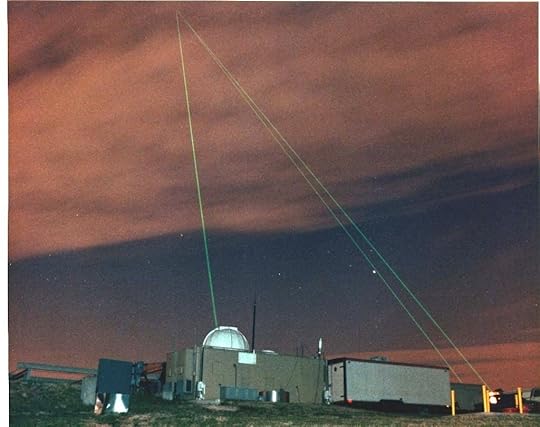

This is what laser weapons ought to look like

This is what laser weapons ought to look like(Image credit: NASA)I enjoy reading science fiction (or watching a sci fi movie) as much as the next nerd, and it's fascinating to speculate on the similarities and differences between the science and technology in the fictional world and reality.

In some areas we have gone far beyond the imagination of the fiction writers; in others we haven't come close. One obvious area that we've lagged pretty far behind is in lasers, phasers, blasters or whatever you want to call them. I think one of the most interesting aspects of the Battlestar Galactica reboot is that once they'd established the technology of space flight, almost every other bit of technology from fridges and phones to weaponry was pretty much late 20th century standard. So any shooting was done with old fashioned bullets. And it's certainly the way things have been in the real world - until now.

The US has been experimenting with laser weapons on ships for some while, but they've now come up with a demo video of their most impressive toy to date. Ships make ideal platforms for lasers. They're big enough to deal with the large-scale equipment needed to power up a major laser, and ships are infamously bad places to fire weapons with recoil (this is why rockets were developed as weapons in the West), from which lasers are wonderfully free.

So here you go: fill your boots with the sight of a genuine laser weapon in action, doing suitably destructive (and pinpoint targeted) stuff. The only disappointment is, if course, it doesn't really look like it's a laser in action. If there's one thing Hollywood has taught us, it's that when you fire a laser you see a bright, coruscating beam in the air. But here the operator presses a button on his video-game like console and instantly the hit happens with nothing visible or audible in between.

It's not likely to be the future of warfare on a large scale, at least for some considerable time, as these things are extremely expensive and quite possibly a little temperamental right now. But this a reality. To quote the US Navy Office of Information 'Laser weapon capability is now allowing operation aboard ships at sea.' Which I think, in English, means 'We are ready to use this for real.'

Published on December 11, 2014 00:50

December 10, 2014

Don't put magicians on pedestals

James RandiOver the years, magicians like Harry Houdini and James Randi have shown time and again that they have ideal skills for spotting and debunking fraudulent claims of magical abilities and mental powers. In the Telegraph yesterday, though, Will Storr had a go at 'debunking the king of the debunkers', demonstrating that Randi himself, now 87 (according to his article, or 86 according to Wikipedia), was not all he seemed. For me, this was a wonderful example of entirely missing the point.

James RandiOver the years, magicians like Harry Houdini and James Randi have shown time and again that they have ideal skills for spotting and debunking fraudulent claims of magical abilities and mental powers. In the Telegraph yesterday, though, Will Storr had a go at 'debunking the king of the debunkers', demonstrating that Randi himself, now 87 (according to his article, or 86 according to Wikipedia), was not all he seemed. For me, this was a wonderful example of entirely missing the point.Storr makes three main accusations. That Randi has at some point been doubtful about the science behind climate change, that he was intolerant to drug users and that he had lied about replicating Rupert Sheldrake's dog experiments, in which Sheldrake claims to have shown that at dog was able to predict when its owner would return home.

The first two, frankly, are hardly worth considering as they are classic type failure errors. Being good at debunking fraudulent psychics does not make you a climate change expert. Why should it? And some perfectly respectable scientists have doubts about some aspects of climate change science. It's the nature of science - it's not a belief system where you have to sign up to everything it says in the big book. As for the attitude to drug users, again, so what? You don't have to be a nice person to be good at your job. So that leaves us with the strange incident of the dog.

It seems likely, if we take Storr's article at face value, that Randi did indeed claim to have replicated an experiment when he hadn't done so. This isn't good. But in a sense it is the inevitable reverse face of the reason that Randi has done his job so well in the first place. Randi has always argued that scientists are not very good at devising tests that prevent those with a stage magician's skills from cheating, or at detecting such cheating in action. What you need, he says, is a magician. And he has proved time and again that he is right. Scientists don't have the expertise of a magician. Well, guess what? Magicians don't have the expertise of a scientist either. Randi isn't a scientist. So why are we surprised when Randi fails to operate in a proper scientific fashion over the Sheldrake business?

I'm not defending Randi in any way for what he is accused of doing. If true, it was bad science, the kind of thing that gets a scientist kicked out of his job. But it doesn't in any way detract from the useful service Randi has provided over many years in devising tests and pointing out the flaws in scientific studies of ESP and the like. Has Storr shown that Randi is sometimes a liar? Quite possibly - and that's why he's good at his job. All magicians are liars by trade, even if they don't always use words to do it. Deception is their business. Perhaps the problem is the fuzzy nature of Randi's skeptical foundation JREF, which gives the veneer of science to what never really deserved that label.

When I read Storr's article, I got the impression of reading the words of a fan who discovers his idol has feet of clay. The same as those who discover their favourite singer has an unpleasant private life. Or that a Nobel Prize winning scientist had unacceptable views on other topics. Welcome to the real world, Mr Storr.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on December 10, 2014 00:50