Brian Clegg's Blog, page 51

August 9, 2016

Grammar dilemma

MGS did me proud - but we don't need more

MGS did me proud - but we don't need more(as it happens it's not a grammar school now)There is some talk of the government allowing expansion of grammar schools (high schools that only admit the brighter students, not the US use of the term) - which I suspect would be a terrible idea.

Like Theresa May, I benefited from a grammar school education and loved it, and had I not attended Manchester Grammar School, it's highly probable I would not have got into Cambridge. But the trouble with this kind of thinking is that it's typical bad analysis driven by individual experience, rather than a proper critical assessment.

As far as I can see there are two problems with grammar schools. The biggest is that they are fine for those who attend - but the remaining students who get sent of to what were called secondary moderns, in effect a second class school, suffer from this process. As a result of a single test - one that is typical of the type of test that only monitors the ability to pass that test - children are separated into sheep and goats. Families are divided. And you can say all the nice words you like about how there is no 'second best' - the fact remains that the non-grammar schools, whatever they choose to call them now, get a lower quality of teaching staff than the grammars and become educational dead ends.

The second issue is that all the actual data-driven evidence points to very little enhancement of that key driver for the supporters of grammar schools (or so they say), social mobility. When comparisons are made with comprehensives, there is little difference on the measures generally used.

It might sound as if there is an inconsistency between my comment about going to Cambridge and the previous paragraph. I was the first from my mostly working class family to go to university, and MGS helped me get to that hallowed location. The reason I say this is that what I do think is true is that grammar schools were better at taking on private schools in providing the kind of edge the top universities are looking for in a candidate. I would still have gone to university, but not to Cambridge. And that is a different measure from social mobility. I think it says more about the unfair advantages provided to private school students than it does about the benefits of grammar schools.

I'm not against streaming. Comprehensives should, and often do teach different ability students in different ways. And just because you are great at, say, maths and science, doesn't mean you'll be good at languages. Streaming is a much more flexible tool than selective schooling. But grammar schools, I would suggest, are designed to address entirely the wrong problem - how to compete with private schools. And they should be entirely removed, not encouraged.

Published on August 09, 2016 01:25

August 8, 2016

Sandlands - Rosy Thornton - review

Traditional holiday reading involves the huge, wrist-bending saga, but my favourite books to take away on a break are collections of short stories. There's something about the ephemeral nature of short stories that fits perfectly with that strangely detached-from-reality feeling of being on holiday. This year I'm opting for three very different collections: The Collected Stories of Grace Paley, Rogues - an SF and fantasy collection edited by George R. R. Martin and Gardner Dozois - and, first, Sandlands by Cambridge academic and novelist Rosy Thornton.

Traditional holiday reading involves the huge, wrist-bending saga, but my favourite books to take away on a break are collections of short stories. There's something about the ephemeral nature of short stories that fits perfectly with that strangely detached-from-reality feeling of being on holiday. This year I'm opting for three very different collections: The Collected Stories of Grace Paley, Rogues - an SF and fantasy collection edited by George R. R. Martin and Gardner Dozois - and, first, Sandlands by Cambridge academic and novelist Rosy Thornton.It's a bit of generalisation, but I'd say short stories fall into two broad categories - there are mood pieces, which don't necessarily have much of a story, but give the feel of a place or time or person, and there are twist-in-the-tail pieces, where we think we know what's happening, but at some point, often near the end, we find that things are very different from expectation. Many of Rosy Thornton's stories in Sandlands are an interesting hybrid, where a lot is about a sense of place (that place mostly being Suffolk, near Aldborough), but the twist in the tail becomes more of a connection in the tail, where something occurring in that distinctive landscape suddenly and intimately ties into an aspect of the protagonist's life.

This is distinctly reminiscent of the importance of location in the work of one of my favourite authors, Alan Garner. Garner's mostly Cheshire landscapes influence and inhabit his characters, and there is no doubt that Thornton also brings the East Anglian countryside and its inhabitants in that particular corner of Suffolk - both human or animal - into the storytelling to have a powerful effect on the protagonists' lives. As the cover suggests, one of those animals is a barn owl, whose ghostly presence acts as a kind of mute guardian - but there is also a white deer, an injured fox and many more to add to the collection. Another frequent theme running through the stories is death, though not in a morbid sense, more as another of the everyday fixtures of life close to the land.

It's difficult to review individual stories, because to describe them in any detail can give too much away. However it doesn't do any harm to pick out some little points - I was particularly impressed with the link in the tail of the story featuring the fox, which also brings in the sogginess of an East Anglian landscape feeling the brunt of climate change (not to mention the impact of sea level rise). And the story involving the owl, again like the best of Alan Garner, has a poignancy that spans time as well being imbued with the sense of place. The variety was excellent, whether it was an electronic ghost story for the twenty-first century or a sadly rare story that brings in one of my favourite places, Cambridge, where the stark University Library plays its part (though the Suffolk coast is still more important).

Just occasionally the link in the tail was slightly predictable - although I loved the almost tangible atmosphere of a story mostly set in a church tower ringing chamber, I saw the ending coming a mile away. There was also a story where an academic stood in for vicar on maternity leave, where the concept was wonderful, but the overall feel was let down by inaccurate details of village church life - rather than a single stand-in, key to the story, such gaps are in practice dealt with using a hotchpotch of cover from local clergy - and the idea that a village PCC would be able to offer funds to regularly subsidise events the way this one does just doesn't ring true.

These, however, were small isolated points that only surface for the very picky reader in an otherwise delightful landscape of story. And, of course, one of the joys of a short story collection is that even if one story isn't quite your cup of tea (I should emphasise I enjoyed even those two), another one will be along soon with a totally different protagonist and storyline.

All in all a wonderful collection that will play with your emotions, deliver over and over, and often make you pause at the end of the story to savour its impact.

Sandlands is available from amazon.co.uk now and amazon.com from October 2016.

Published on August 08, 2016 00:55

Sandilands - Rosy Thornton - review

Traditional holiday reading involves the huge, wrist-bending saga, but my favourite books to take away on a break are collections of short stories. There's something about the ephemeral nature of short stories that fits perfectly with that strangely detached-from-reality feeling of being on holiday. This year I'm opting for three very different collections: The Collected Stories of Grace Paley, Rogues - an SF and fantasy collection edited by George R. R. Martin and Gardner Dozois - and, first, Sandlands by Cambridge academic and novelist Rosy Thornton.

Traditional holiday reading involves the huge, wrist-bending saga, but my favourite books to take away on a break are collections of short stories. There's something about the ephemeral nature of short stories that fits perfectly with that strangely detached-from-reality feeling of being on holiday. This year I'm opting for three very different collections: The Collected Stories of Grace Paley, Rogues - an SF and fantasy collection edited by George R. R. Martin and Gardner Dozois - and, first, Sandlands by Cambridge academic and novelist Rosy Thornton.It's a bit of generalisation, but I'd say short stories fall into two broad categories - there are mood pieces, which don't necessarily have much of a story, but give the feel of a place or time or person, and there are twist-in-the-tail pieces, where we think we know what's happening, but at some point, often near the end, we find that things are very different from expectation. Many of Rosy Thornton's stories in Sandlands are an interesting hybrid, where a lot is about a sense of place (that place mostly being Suffolk, near Aldborough), but the twist in the tail becomes more of a connection in the tail, where something occurring in that distinctive landscape suddenly and intimately ties into an aspect of the protagonist's life.

This is distinctly reminiscent of the importance of location in the work of one of my favourite authors, Alan Garner. Garner's mostly Cheshire landscapes influence and inhabit his characters, and there is no doubt that Thornton also brings the East Anglian countryside and its inhabitants in that particular corner of Suffolk - both human or animal - into the storytelling to have a powerful effect on the protagonists' lives. As the cover suggests, one of those animals is a barn owl, whose ghostly presence acts as a kind of mute guardian - but there is also a white deer, an injured fox and many more to add to the collection. Another frequent theme running through the stories is death, though not in a morbid sense, more as another of the everyday fixtures of life close to the land.

It's difficult to review individual stories, because to describe them in any detail can give too much away. However it doesn't do any harm to pick out some little points - I was particularly impressed with the link in the tail of the story featuring the fox, which also brings in the sogginess of an East Anglian landscape feeling the brunt of climate change (not to mention the impact of sea level rise). And the story involving owl, again like the best of Alan Garner, has a poignancy that spans time as well being imbued with the sense of place. The variety was excellent, whether it was an electronic ghost story for the twenty-first century or a sadly rare story that brings in one of my favourite places, Cambridge, where the stark University Library plays its part (though the Suffolk coast is still more important).

Just occasionally the link in the tail was slightly predictable - although I loved the almost tangible atmosphere of a story mostly set in a church tower ringing chamber, I saw the ending coming a mile away. There was also a story where an academic stood in for vicar on maternity leave, where the concept was wonderful, but the overall feel was let down by inaccurate details of village church life - rather than a single stand-in, key to the story, such gaps are in practice dealt with using a hotchpotch of cover from local clergy - and the idea that a village PCC would be able to offer funds to regularly subsidise events the way this one does just doesn't ring true.

These, however, were small isolated points that only surface for the very picky reader in an otherwise delightful landscape of story. And, of course, one of the joys of a short story collection is that even if one story isn't quite your cup of tea (I should emphasise I enjoyed even those two), another one will be along soon with a totally different protagonist and storyline.

All in all a wonderful collection that will play with your emotions, deliver over and over, and often make you pause at the end of the story to savour its impact.

Sandlands is available from amazon.co.uk now and amazon.com from October 2016.

Published on August 08, 2016 00:55

August 5, 2016

Does antimatter matter?

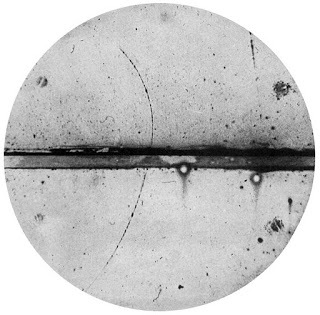

Cloud chamber image of the first observed positron

Cloud chamber image of the first observed positron(Source: Wikipedia)When I was a teenager and ill I used to revert to childhood reading - Famous Five and the like. Recently confined to bed with norovirus, I found that all my brain could cope with was guff such as the output of Dan Brown, so I gritted my teeth and read Angels and Demons. As always with Brown, most of the 'fact' content of the book was anything but factual. However, I thought it would be worth a quick trip into the nature of the central McGuffin of the story, antimatter. It may be Brown's super bomb and the power source of the fictional USS Enterprise, but it is real.

Antimatter is like the familiar stuff that makes up our world, but charged particle have the opposite charge (it's a little more complicated with uncharged particles). Instead of negative electrons, antimatter has positive anti-electrons, better known as positrons. Replacing positive protons in the nucleus, an anti-atom would have negatively charged anti-protons. It’s possible in principle to do anything with antimatter that can be done with ordinary matter. You could build an anti-table or an anti-house on an anti-world as long as you can handle the material. Antimatter has mass and behaves much like ordinary matter does (though as mentioned previously on this blog, it's just possible that it doesn't have quite the same attitude to gravity). But don’t expect to go out and buy some. Doing anything practical with antimatter is tricky. When matter and antimatter get together, both are destroyed, converted into pure energy.

The simplest reaction between the two is when an electron and a positron combine. The mass of the particles is converted into energy in the form of two photons of light (gamma rays), the amount predicted by Einstein’s famous equation E=mc2 – the energy produced is equal to the combined mass of the particles multiplied by the square of the speed of light. Because of this tendency to annihilate, very little free antimatter is found in the universe - at least anywhere we can see.

There is still a debate about where all the antimatter has gone. The Big Bang, starting with pure energy, should have produced equal amounts of matter and anti-matter, which then could wipe each other out, reverting to a universe full of energy. That this didn’t happen is usually explained by assuming that subtle differences in the properties of matter and anti-matter meant that there was a little extra matter left over. As few as one particle in a billion may have survived the initial matter/anti-matter wipe-out. But that was enough. However, this story is speculative at best at the moment.

The amount of energy generated from the interaction of matter and antimatter is vast. One kilogram of matter/antimatter coming together would produce around 1017 joules (1 with seventeen 0’s after it). That’s the energy output of a decent sized power station running for six years. However, don't expect, as Dan Brown appears to think, that antimatter is a new and wonderful power source. It's just a way to store energy - it takes significantly more energy to make the antimatter than is released when it annihilates. It's not a source of energy in the way a fuel in the way that sunlight or gas or radioactive materials are - instead it's more like a battery where you can store a vast amount of energy in a very small space. It's a battery with serious attitude.

Published on August 05, 2016 01:07

August 2, 2016

Celebrating pure research

There is often a degree of desperation in the way that some scientists try to justify expenditure on pure research by pointing out spinoff benefits. Such benefits certainly exist, but often they are spurious as a justification, because it would be easily possible to derive the same benefits for far less money. The fact is that fundamental research is important in its own right and its proponents shouldn't attempt this kind of indirect benefit claim.

There is often a degree of desperation in the way that some scientists try to justify expenditure on pure research by pointing out spinoff benefits. Such benefits certainly exist, but often they are spurious as a justification, because it would be easily possible to derive the same benefits for far less money. The fact is that fundamental research is important in its own right and its proponents shouldn't attempt this kind of indirect benefit claim.I was struck by this recently when reading a not-atypical defence of the expenditure on CERN, home of the Large Hadron Collider, by saying 'the biggest impact of CERN on humanity has not been the discovery of the Higgs boson but rather the invention of the World Wide Web.' The author went on to point out how much commercial business the web generates.

I'm afraid this is both iffy justification and bad history of technology. I'm not doing down what Tim Berners-Lee achieved. But the web, or something like it, was a technology waiting to happen. The internet was already well-established. The whole idea of hyperlinked documents goes back to Ted Nelson's work in the mid-60s. The architecture might have turned out subtly different, and CERN certainly kickstarted things, but something like this was on the (hyper)cards.

It's difficult, but I think scientists need to be brave and should not try to justify this kind of work in terms of its spinoffs, any more than NASA should try to do this in its occasional feeble attempts to excuse expenditure on a space programme by the spinoffs. We should be finding out about our universe because it's what makes us human and makes life worthwhile. Let's celebrate pure research, not try to turn it into a weakly argued generator of novelties.

Published on August 02, 2016 01:45

August 1, 2016

At Cross Purposes - Review

This is a narrow focus review: if, like me, you are fond of church music and the Anglican cathedral choral tradition (something I was introduced to age 18 on joining a Cambridge college chapel choir), read on.

This is a narrow focus review: if, like me, you are fond of church music and the Anglican cathedral choral tradition (something I was introduced to age 18 on joining a Cambridge college chapel choir), read on.Most of us are probably aware that the big cathedrals have professional organists and semi-pro choirs, working at the highest levels of musical performance. In his memoirs, Michael Smith, organist and choirmaster at Llandaff Cathedral from 1974 to 1999, gives the inside story of what was often a battle to maintain such singing standards. This might sound a touch dull - and there certainly are many small and personal events in this 400 page book, but for those who are interested there are also some fascinating stories, from a murder to legal threats, conspiracy and downright managerial incompetence.

LLandaff was unique among the Welsh cathedrals in keeping up a full scale cathedral choir contribution, singing services six days a week, with a choir of boys and men. The men, as at most major cathedrals, were paid a relative pittance for a job they loved, in theory in combination with accommodation and other opportunities, though the accommodation part was one of the many battles Smith would have with the management of the cathedral: the Dean and chapter.

In keeping the cathedral choir going through many musical successes, Smith had two big problems. One was the bizarre setup at Llandaff: the cathedral was also a parish church, and effectively operated with two separate management structures, even two choirs and totally separate services. This inevitably led to clashes of priority and finances. The other, even bigger, issue was that the management of the relationship between Smith and his employer, the Dean and chapter, was disastrous. Rather than talk about things, everything seemed to be done through letters - which usually seemed to be entirely ignored by the management side. This led to Smith's house becoming dangerously in need of repairs, a total mismatch of salary to other cathedral organists and constant battles over every little detail from who paid the phone bill to a dodgy piano. Other problems arose from the cathedral choir school, which provided the boys for the choir and whose management also seemed both to have serious issues and to be at odds with the school's role as a choir school.

What also comes through strongly is the way that Smith's devotion to a tradition remained constant while society's views gradually shifted, resulting in some unfortunate clashes, all documented here. I can relate to this change in attitude. When I was at school, I sang in a highly rated choir that provided the boys' parts for pieces performed by the Hallé Orchestra and the regime was strict. I can remember things being thrown at choir members who weren't paying attention and others getting detentions just for turning to round to see who had come into a room during a choir practice. Smith never resorted to this kind of regime, but getting a choir to a professional level requires a professional approach, which he had both to his choirs an the music examinations he supervised - and in both cases, towards the end of his career, he was probably unfairly censured for his strictness, at one point being suspended for several months over highly inflated allegations.

Bitterness is a major part of this memoir - combining someone who, I suspect, was always going to be quite a difficult employee with terrible management, leading to a disastrous inability to communicate and get things done. Yet despite that, magnificent music continued to be made. Occasionally an inflexibility comes through that suggests this wasn't entirely one-sided. Smith was, for instance, incredibly reluctant to perform anything in Welsh, despite this being a Welsh cathedral. And he occasionally displayed the musical preferences of a different age when the big hymn books refused to print Welsh tunes because they were too lowbrow: this comes through when he considers the great Welsh tune Blaenwern more suited to a chapel than a cathedral. Yet at the same time there was no doubt that Llandaff was punching far above its weight musically thanks to Smith's efforts.

Whether he is describing conducting wonderful anthems and choral works, gadding around the country and abroad to conferences and to administer music examinations, or taking up Kleeneze sales and market research in an attempt to bolster a meagre income, there's a poignant honesty in these memoirs. It's not a laugh a minute - at times the annual cycle of events can seem to go on for ever - but if you are interested in how this great musical tradition somehow survives against remarkable odds, it's well worth reading Michael Smith's account.

At Cross Purposes is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com.

You can hear Michael Smith's choir in action here in a rather fuzzy recording:

Published on August 01, 2016 02:28

July 29, 2016

Too much or too little change?

This isn't a post about Brexit per se - though I am pleased to discover that as yet the sky seems not to have fallen in - but about an interesting paradox.

This isn't a post about Brexit per se - though I am pleased to discover that as yet the sky seems not to have fallen in - but about an interesting paradox.I was listening to David Aaronovitch's programme about how remainers feel now, broadcast on Radio 4 last night. After a range of interviews, there was a discussion with a couple of people in the studio. One of the questions asked was whether they thought that the same result would have happened in 10 or 15 years time. As Aaronovitch pointed out it's not as obvious an outcome as you might think. The typical reaction might be 'No, because many of the older voters will have died off, so the younger voters, weighted to remain would triumph.' But, of course, it's entirely possible that as younger voters got older they might change their mind - and in 10 to 15 years, the EU might be in such a mess that withdrawing would be even more popular.

However, the paradox arose in a comment analysing why older voters might be more in favour of leaving the EU, which was put down to their being more uncomfortable with change, and so less happy about the way the UK is changing as a result of being in the EU. There could, indeed, be some truth in this. But here's the thing. Leaving the EU is change. A vote for remain was actually a vote to avoid change. Bizarrely, the argument seems to be that apparently in order to move away for change, leavers voted for change. I suspect the driver was not so much a fear of change (the classic metropolitan elite view of what happened) as a desire for change. Whether or not that change is a good thing is an entirely different issue - but change we certainly got. (Unless we're a Labour party leader, of course.)

Published on July 29, 2016 05:17

July 25, 2016

Are smart meters really smart?

My meter is dumb - and I like it that wayInteresting news that British Gas is finally offering the first real benefit to the consumer of having a smart meter - 9 to 5 free electricity on either Saturday or Sunday to people on the appropriate plan. And that's great, possibly - but it also needs to be taken with a pinch of salt.

My meter is dumb - and I like it that wayInteresting news that British Gas is finally offering the first real benefit to the consumer of having a smart meter - 9 to 5 free electricity on either Saturday or Sunday to people on the appropriate plan. And that's great, possibly - but it also needs to be taken with a pinch of salt.I've always been a touch suspicious of the way smart meters are being sold. We have been told that they enable consumers to be more aware of their electricity use, and hence to save money. But I'm not really not convinced that seeing that your kettle uses more electricity when it's boiling water than when it's off is really a great surprise to anyone - even if we can actually see the smart meter while boiling the kettle, which often won't be the case.

In practice, what these meters are primarily about is enabling the energy supply companies to get more of a real time monitoring of individual usage, which in principle could benefit the consumer, but is primarily aimed at being able to extract more cash.

In principle, the British Gas 'all you can eat for free' on a weekend day of your choice 9 to 5 (odd times for the weekend) is a clear benefit to the owner (though it hardly encourages good green thinking - 'Hey let's use as much energy as we can today, it's free!'). And you certainly would save money, estimated to average £60 a year, compared with being on the same tariff without it. However, bear in mind that most households can save between £200 and £300 a year by switching supplier - so it looks suspiciously like offering lollipops to tie the consumer into paying more.

Published on July 25, 2016 00:44

July 22, 2016

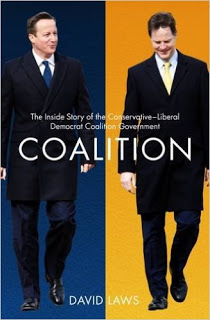

Coalition: David Laws - review

By a genuine coincidence, I ended up reading David Laws' inside account of the five years of Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition in the UK immediately after reading the book form of Yes Minister and Yes Prime Minister - still hilarious after all these years.

By a genuine coincidence, I ended up reading David Laws' inside account of the five years of Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition in the UK immediately after reading the book form of Yes Minister and Yes Prime Minister - still hilarious after all these years.Although Coalition hasn't got anywhere near as much in the way of funny bits as the satire, it is genuinely readable despite its wrist-busting 600+ pages. Laws doesn't have a particularly outstanding writing style, but he comes across as genuine and the book is well structured, in relatively short, themed chunks that tend to span across months or years, rather than trying to do the whole thing in a single, chronological bore-fest. (The effectiveness only breaks down at the end, where it could have done with some serious editor's blue pencil, but that's really only in the short postscript.)

I think two things are particularly fascinating. One is to get a better feel for the characters, many of them still in the Conservative government, as people. We get to used to treating politicians as if they were Spitting Image puppets, simply voicing their extreme views and then being put back in the cupboard, resulting in the kind of extremely negative personal comments made to no one's advantage during the recent EU referendum. Here we see people like David Cameron, George Osborne, Michael Gove and Theresa May more as actual people - we see much rounder personalities: if they're funny, how conservative they and, interestingly, how socially liberal some of them are. Perhaps most fascinating of these are Cameron - who comes across sometimes worryingly like Jim Hacker in Yes Prime Minister - Osborne, displaying a surprisingly human side and Gove - who comes across as both likeable and downright weird, prone to distinctly odd behaviour. Obviously, given turns of events since, it is also fascinating to see the trajectory with which many of the key players went into the EU referendum (which was obviously after the book was written, though thoughts about it coming in the future are often referenced).

The other thing that is interesting is, if we believe Laws, how much they all genuinely put a huge amount off effort into keeping a workable coalition going, and achieved a fair number of positive things between 2010 and 2015. There is also a sad inside view of the pretty much total destruction of the Liberal Democrat party as a result, in part, of the electorate simply not understanding how much they had contributed to the coalition.

Of course, this is one person's view - but Laws seems to have been well-placed to give it and it shows us everything from the workings of the senior civil service (capable of the odd Sir Humphrey moment, despite mostly coming across as very efficient) through to the practicalities of government most of us never get to see. Recommended.

Coalition is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com.

Published on July 22, 2016 01:31

July 20, 2016

The brilliance of stuff that just works

The ticket as it popped up on my

The ticket as it popped up on myphone (original not pixilated)A few years ago, when I first moved over to using Apple, a friend of mine who likes to get up to his elbows in the technology, tweaking this and twerking that, said 'I could never live with that walled garden.' He wasn't talking about some rural pleasure grounds, but rather the way that Apple rigidly controls what does what on its devices.

I can see the point if you are the sort of person who likes to nurgle around changing settings and writing macros and linking box X to widget Y to make things just the way you want them. And I probably was that person in my 20s. But now I just want things to work together, and with a few notable exceptions, the good thing about using Apple is that it all does.

I just had an example of that. I had received an e-ticket notification from Eurostar. On the email it said 'click here to download your ticket'. I did this on my iMac. Up popped a web window showing the ticket. This had a link on it saying 'Click here to send the ticket to your wallet.' Yeah, right, I thought. So I clicked the link. And five seconds later, there was a ticket sitting in the Wallet app on my phone.

I'm not saying this wouldn't necessarily work as well with Android or Windows - it may well do so. But for me, that ability to click a link on my desktop and have a ticket appear as if by magic in the wallet on the phone is why the walled garden can be a lovely place to live.

Published on July 20, 2016 05:56