Brian Clegg's Blog, page 43

April 7, 2017

Avant garde should encourage rebellion

The term 'avant garde' (literally something like 'vanguard' or 'advanced guard', implying being ahead of the pack and outside of the usual boundaries) is one that is proudly adopted by some art. And I think that's fine - but I also think that the artists in question need to expect that their audiences may abandon the reverence that is usually adopted by the audience for traditional art.

Image from

Wikipedia

This occurred to me when a friend was describing attending a play at Bristol's fairly avant garde Old Vic Theatre. Apparently the performance was of a Samuel Beckett radio play, and as Beckett had specified it should never be staged, they told the audience that they had to wear blindfolds. Thinking about this, I realised that my immediate reaction, had I been in the audience, would have been to have cheated and taken the blindfold off once they got started. Because once you break the rules as an artist, why should your audience be forced to stick to the rules? It seemed to me that it was just as acceptable for me as an audience member - as art, if you like - to take off my blindfold as it was for the performers and/or the late Mr Beckett to insist that I wear it.

Image from

Wikipedia

This occurred to me when a friend was describing attending a play at Bristol's fairly avant garde Old Vic Theatre. Apparently the performance was of a Samuel Beckett radio play, and as Beckett had specified it should never be staged, they told the audience that they had to wear blindfolds. Thinking about this, I realised that my immediate reaction, had I been in the audience, would have been to have cheated and taken the blindfold off once they got started. Because once you break the rules as an artist, why should your audience be forced to stick to the rules? It seemed to me that it was just as acceptable for me as an audience member - as art, if you like - to take off my blindfold as it was for the performers and/or the late Mr Beckett to insist that I wear it.

As I wasn't there, I don't know how the artists would have reacted. I do know that on other occasions when the audience has not behaved as expected, the answer has been 'not very well.' This was certainly the case in one of the early performances of one of Stockhausen's more approachable pieces, Stimmung. In the piece, lasting about an hour, a cappella performers sing a single chord. However, it is a genuinely interesting piece because they vary how they sing the notes throughout - using different octaves, sounds and words, tones - I really rather like it. At the performance in question, the audience members started to join in, singing in their own notes in the chord. Now, to me, that's brilliant. But apparently those involved (I can't remember if it was Stockhausen himself or just the performers) were furious and stopped the performance.

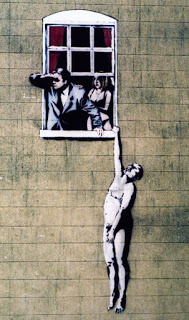

As I quite regularly go to Bristol, I'd also say the same goes for those who add things to Banksy paintings. The whole concept of painting on walls is breaking the rules - so you can hardly complain when someone else does the same thing. In some cases where a Banksy has been 'defaced' I think the result is an improvement. In others it's borderline. The image shown here has according to Wikipedia been 'defaced with blue paint'. Actually the 'defacing' is quite effective as it looks as if someone has shot at the people with a paint gun, which itself could be interpreted artistically (in fact, I didn't know it was 'defaced' until I looked it up). Admittedly if all someone does is scrawl a tag over it, it's not a great contribution. But even so, I'm not sure we have any right to complain. If someone does it to a conventional piece of art in a gallery, that is totally unacceptable. But if you really want to be avant garde, then you should go with the flow when it comes to others contributing. Get antsy about it, and it shows that underneath you are still very conventional.

Image from

Wikipedia

This occurred to me when a friend was describing attending a play at Bristol's fairly avant garde Old Vic Theatre. Apparently the performance was of a Samuel Beckett radio play, and as Beckett had specified it should never be staged, they told the audience that they had to wear blindfolds. Thinking about this, I realised that my immediate reaction, had I been in the audience, would have been to have cheated and taken the blindfold off once they got started. Because once you break the rules as an artist, why should your audience be forced to stick to the rules? It seemed to me that it was just as acceptable for me as an audience member - as art, if you like - to take off my blindfold as it was for the performers and/or the late Mr Beckett to insist that I wear it.

Image from

Wikipedia

This occurred to me when a friend was describing attending a play at Bristol's fairly avant garde Old Vic Theatre. Apparently the performance was of a Samuel Beckett radio play, and as Beckett had specified it should never be staged, they told the audience that they had to wear blindfolds. Thinking about this, I realised that my immediate reaction, had I been in the audience, would have been to have cheated and taken the blindfold off once they got started. Because once you break the rules as an artist, why should your audience be forced to stick to the rules? It seemed to me that it was just as acceptable for me as an audience member - as art, if you like - to take off my blindfold as it was for the performers and/or the late Mr Beckett to insist that I wear it.As I wasn't there, I don't know how the artists would have reacted. I do know that on other occasions when the audience has not behaved as expected, the answer has been 'not very well.' This was certainly the case in one of the early performances of one of Stockhausen's more approachable pieces, Stimmung. In the piece, lasting about an hour, a cappella performers sing a single chord. However, it is a genuinely interesting piece because they vary how they sing the notes throughout - using different octaves, sounds and words, tones - I really rather like it. At the performance in question, the audience members started to join in, singing in their own notes in the chord. Now, to me, that's brilliant. But apparently those involved (I can't remember if it was Stockhausen himself or just the performers) were furious and stopped the performance.

As I quite regularly go to Bristol, I'd also say the same goes for those who add things to Banksy paintings. The whole concept of painting on walls is breaking the rules - so you can hardly complain when someone else does the same thing. In some cases where a Banksy has been 'defaced' I think the result is an improvement. In others it's borderline. The image shown here has according to Wikipedia been 'defaced with blue paint'. Actually the 'defacing' is quite effective as it looks as if someone has shot at the people with a paint gun, which itself could be interpreted artistically (in fact, I didn't know it was 'defaced' until I looked it up). Admittedly if all someone does is scrawl a tag over it, it's not a great contribution. But even so, I'm not sure we have any right to complain. If someone does it to a conventional piece of art in a gallery, that is totally unacceptable. But if you really want to be avant garde, then you should go with the flow when it comes to others contributing. Get antsy about it, and it shows that underneath you are still very conventional.

Published on April 07, 2017 02:17

April 6, 2017

Time to end April fool news

Last Saturday saw the usual spate of 'April fool' spoof news stories - but I think it's time this practice stopped.

In the early days, these stories were delightful. I remember seeing a re-run of the Panorama spaghetti harvest film as a child (probably on its 10th anniversary) and loved it. At university, I read with glee the Guardian's superb San Seriffe feature with all the wonderful detail of this supposed travelling island nation. However, I'd say the news reporting world has changed in two ways that make the whole business not so funny - and when we get flooded with these stories, many of them lack the originality and sheer madness of these early attempts.

The first change is the rise of comedy news sources like The Onion and The Daily Mash. They churn out several such stories a day - we really don't need extra ones on April 1. And then there's the rise of post-truth, fake news reporting. And that brings it home that it's not acceptable for a proper news outlet to lie to us just because they think it's funny to do so. To take a trivial example, my favourite newspaper, the i, ran a story that Southern Rail was going to start standing-only carriages to pack more people in. I simply took that as fact - it wasn't silly enough to do its job. As it happened I saw the 'retraction' on the following Monday, but if I hadn't, it would have become fake news for me - and 'Bur we were just being funny, not lying' isn't a good enough reason for doing that to your audience.

So let's give it a miss next year. Please? Yes, fine, I don't mind the occasional, large scale extravaganza like the spaghetti harvest or San Seriffe. But stop with the barrage of silly little stories that could all too easily be true.

If you've never seen the spaghetti harvest, this mini-documentary shows the original material and fills in some of the context of it being put together. It's only 4 minutes and well worth enjoying:

In the early days, these stories were delightful. I remember seeing a re-run of the Panorama spaghetti harvest film as a child (probably on its 10th anniversary) and loved it. At university, I read with glee the Guardian's superb San Seriffe feature with all the wonderful detail of this supposed travelling island nation. However, I'd say the news reporting world has changed in two ways that make the whole business not so funny - and when we get flooded with these stories, many of them lack the originality and sheer madness of these early attempts.

The first change is the rise of comedy news sources like The Onion and The Daily Mash. They churn out several such stories a day - we really don't need extra ones on April 1. And then there's the rise of post-truth, fake news reporting. And that brings it home that it's not acceptable for a proper news outlet to lie to us just because they think it's funny to do so. To take a trivial example, my favourite newspaper, the i, ran a story that Southern Rail was going to start standing-only carriages to pack more people in. I simply took that as fact - it wasn't silly enough to do its job. As it happened I saw the 'retraction' on the following Monday, but if I hadn't, it would have become fake news for me - and 'Bur we were just being funny, not lying' isn't a good enough reason for doing that to your audience.

So let's give it a miss next year. Please? Yes, fine, I don't mind the occasional, large scale extravaganza like the spaghetti harvest or San Seriffe. But stop with the barrage of silly little stories that could all too easily be true.

If you've never seen the spaghetti harvest, this mini-documentary shows the original material and fills in some of the context of it being put together. It's only 4 minutes and well worth enjoying:

Published on April 06, 2017 00:09

April 2, 2017

Amazon Echo review

For several months now I have had Amazon's Echo devices, with the Alexa voice-operated assistant in the house. To test their effectiveness, I have the two main Echo variants - Echo and Echo Dot, plus a small Phillips Hue smart lighting system to see how the Echoes interact with home automation. I'll take each separately, starting with the full size Echo.

Amazon Echo

The Echo looks like a wireless speaker until you use the trigger word 'Alexa', at which point a funky blue glowing ring appears on top to indicate it is listening (the glow even attempts to point towards your voice). The Echo can cope with a vast number of 'skills' - responses to voice commands - from playing music to ordering an Uber taxi. Some of the skills are excellent, though I think it's fair to say that 95% of them are either too local to somewhere in America or too pointless to be of any use.

The Echo looks like a wireless speaker until you use the trigger word 'Alexa', at which point a funky blue glowing ring appears on top to indicate it is listening (the glow even attempts to point towards your voice). The Echo can cope with a vast number of 'skills' - responses to voice commands - from playing music to ordering an Uber taxi. Some of the skills are excellent, though I think it's fair to say that 95% of them are either too local to somewhere in America or too pointless to be of any use.

Our most frequent use of the full-size Echo is playing music and radio. We opted for access to Amazon's full 50 million+ music library just on the one device, which costs a reasonable £3.99 a month. This is excellent whether you want to listen to some new release, select a playlist or dig out a prog rock classic. As I demonstrate in the video at the end of the review, it's not so good with classical music, where it struggles with the idea of something being 'by' a composer (as opposed to a performer), doesn't like non-English titles and is too song-oriented to easily select long pieces. There is a way round it - you can set up a playlist on your computer with anything you like in it, then the Echo will play it. There's also easy access to internet radio - say 'Play BBC Radio 4' and you're away.

It might seem trivial, but the hands-free manipulation of music and radio (especially if you're cooking) is very effective. Outside of these uses, our main other ways of employing the Echo is as an information source or for home automation. (No need to Shazam an unfamiliar piece playing from its library, by the way - just ask Alexa who it is and she gives the details.) Among Alexa's talents are being able to read the opening of a Wikipedia entry, giving a local weather forecast, converting Fahrenheit to Celsius (useful if you have a US recipe) and more. She'll also tell you a (bad) joke or respond wittily to some queries. We also use Alexa to set timers, which again is great in the kitchen.

To test home automation, we've tied the Echo in to the Phillips Hue lighting in the utility room next to the kitchen where the Echo is located. It works fine - you can ask Alexa to turn the light on, off or to a desired level. But it's only really an advantage when you're not near the light (you can control Alexa from the opposite end of the kitchen). Otherwise it feels a lot more work than just pressing a switch. Also, Alexa insists on saying 'Okay' when she's done the automation task, which becomes irritating.

Of the other skills that felt like they might be useful, most are just too restricted to be useful. So, for example, I can check the trains on my usual route or the traffic on my usual journey... but I don't commute, so I don't have a usual route. I can order the last thing I ordered from Just Eat... but I can't remember what it was, and usually tweak the order. I can get an Uber... but we don't have Uber here. I can ask Jamie Oliver for a recipe... but not for a specific meal - I have to choose, say, a chicken dish and then hear what's on offer and choose one. Alexa can add items to a to-do list, shopping list or a Google Calendar, but this is quite messy in practice (she can't delete items, for instance) and I don't find I use this at all.

For me the main Echo is worth it as a hands free music and radio speaker, with a bit of info retrieval thrown in. The sound quality is fine for kitchen listening. A definite plus.

The Echo is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com

Amazon Echo Dot

The Dot looks like the top cut off the full size Echo and is extremely good value for what it does. In effect it has the same capabilities as the main Echo, but only a tiny speaker, so it's no better for playing music than a mobile phone. We tested ours in the living room where this limitation isn't too much of a problem, as you can ask the Dot to pair with a Bluetooth speaker (in our case, a TV sound bar) and play through that (once you've set it up, it's simply a matter of saying 'Alexa Connect'), which then produces excellent sound.

The Dot looks like the top cut off the full size Echo and is extremely good value for what it does. In effect it has the same capabilities as the main Echo, but only a tiny speaker, so it's no better for playing music than a mobile phone. We tested ours in the living room where this limitation isn't too much of a problem, as you can ask the Dot to pair with a Bluetooth speaker (in our case, a TV sound bar) and play through that (once you've set it up, it's simply a matter of saying 'Alexa Connect'), which then produces excellent sound.

In practice, we've found this Echo far less useful. We tend not to play music or listen to the radio in the living room much, so our use is limited to the occasional information request and automation. This is more useful than the single bulb in the utility room, as Alexa is in charge of two table lamps which she can turn on/off together or separately and it is easier to use the automation than going from table to table.

One disadvantage here is that Alexa is quite often fooled by the TV. Several times a week she will leap in, trying to answer a question she thinks the TV has asked her. The first times this happen are decidedly spooky... then it just becomes irritating. Still - it is incredible value for what it does.

The Echo Dot is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com

Phillips Hue

Although not part of the Echo system, I ought to say a few words about Hue in its own right. This consists of a central controller linked to you wifi and individual bulbs that are also linked, meaning you can control those bulbs from a smartphone app. The system works well with Echo, but also has some great features standalone. From my phone, I can control the light bulbs in the system, switching any of them on and off or dimming them with a slider. (If I had fancy coloured bulbs, I could also do colours, but I stuck to white.)

By default you can only do this within the house, but if you register with Hue's system, you can also do it remotely via the internet. I find the best part of this extended facility is that it can detect when you are coming home and it's after dusk and will automatically switch selected lights on - so you never come home to a dark house.

We have also installed a Hue wall switch in the utility room, which gives on/off and fade controls for that light. The Hue bulbs we have in table lights are easier to control via the app or an Amazon Echo than manually, but the single bulb in the utility room often seemed harder to deal with that way, so now we have the option to do this manually, without disabling the remote control, which would happen if we used the wall switch.

I don't think I'd ever extend it to the whole house - but it's excellent having this available in our test rooms.

Hue is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com

Is it for me?

I wouldn't get rid of our home automation, and would happily extend it to include, for example, a smart thermostat. We love our main Echo as a music player/hands free radio, but a lot of the extra 'skills' seem more for show than practical purposes. So it's restrained enthusiasm all round.

Here's that video again, attempting to get Alexa to play Schoenberg's Verklärte Nacht:

Amazon Echo

The Echo looks like a wireless speaker until you use the trigger word 'Alexa', at which point a funky blue glowing ring appears on top to indicate it is listening (the glow even attempts to point towards your voice). The Echo can cope with a vast number of 'skills' - responses to voice commands - from playing music to ordering an Uber taxi. Some of the skills are excellent, though I think it's fair to say that 95% of them are either too local to somewhere in America or too pointless to be of any use.

The Echo looks like a wireless speaker until you use the trigger word 'Alexa', at which point a funky blue glowing ring appears on top to indicate it is listening (the glow even attempts to point towards your voice). The Echo can cope with a vast number of 'skills' - responses to voice commands - from playing music to ordering an Uber taxi. Some of the skills are excellent, though I think it's fair to say that 95% of them are either too local to somewhere in America or too pointless to be of any use.Our most frequent use of the full-size Echo is playing music and radio. We opted for access to Amazon's full 50 million+ music library just on the one device, which costs a reasonable £3.99 a month. This is excellent whether you want to listen to some new release, select a playlist or dig out a prog rock classic. As I demonstrate in the video at the end of the review, it's not so good with classical music, where it struggles with the idea of something being 'by' a composer (as opposed to a performer), doesn't like non-English titles and is too song-oriented to easily select long pieces. There is a way round it - you can set up a playlist on your computer with anything you like in it, then the Echo will play it. There's also easy access to internet radio - say 'Play BBC Radio 4' and you're away.

It might seem trivial, but the hands-free manipulation of music and radio (especially if you're cooking) is very effective. Outside of these uses, our main other ways of employing the Echo is as an information source or for home automation. (No need to Shazam an unfamiliar piece playing from its library, by the way - just ask Alexa who it is and she gives the details.) Among Alexa's talents are being able to read the opening of a Wikipedia entry, giving a local weather forecast, converting Fahrenheit to Celsius (useful if you have a US recipe) and more. She'll also tell you a (bad) joke or respond wittily to some queries. We also use Alexa to set timers, which again is great in the kitchen.

To test home automation, we've tied the Echo in to the Phillips Hue lighting in the utility room next to the kitchen where the Echo is located. It works fine - you can ask Alexa to turn the light on, off or to a desired level. But it's only really an advantage when you're not near the light (you can control Alexa from the opposite end of the kitchen). Otherwise it feels a lot more work than just pressing a switch. Also, Alexa insists on saying 'Okay' when she's done the automation task, which becomes irritating.

Of the other skills that felt like they might be useful, most are just too restricted to be useful. So, for example, I can check the trains on my usual route or the traffic on my usual journey... but I don't commute, so I don't have a usual route. I can order the last thing I ordered from Just Eat... but I can't remember what it was, and usually tweak the order. I can get an Uber... but we don't have Uber here. I can ask Jamie Oliver for a recipe... but not for a specific meal - I have to choose, say, a chicken dish and then hear what's on offer and choose one. Alexa can add items to a to-do list, shopping list or a Google Calendar, but this is quite messy in practice (she can't delete items, for instance) and I don't find I use this at all.

For me the main Echo is worth it as a hands free music and radio speaker, with a bit of info retrieval thrown in. The sound quality is fine for kitchen listening. A definite plus.

The Echo is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com

Amazon Echo Dot

The Dot looks like the top cut off the full size Echo and is extremely good value for what it does. In effect it has the same capabilities as the main Echo, but only a tiny speaker, so it's no better for playing music than a mobile phone. We tested ours in the living room where this limitation isn't too much of a problem, as you can ask the Dot to pair with a Bluetooth speaker (in our case, a TV sound bar) and play through that (once you've set it up, it's simply a matter of saying 'Alexa Connect'), which then produces excellent sound.

The Dot looks like the top cut off the full size Echo and is extremely good value for what it does. In effect it has the same capabilities as the main Echo, but only a tiny speaker, so it's no better for playing music than a mobile phone. We tested ours in the living room where this limitation isn't too much of a problem, as you can ask the Dot to pair with a Bluetooth speaker (in our case, a TV sound bar) and play through that (once you've set it up, it's simply a matter of saying 'Alexa Connect'), which then produces excellent sound.In practice, we've found this Echo far less useful. We tend not to play music or listen to the radio in the living room much, so our use is limited to the occasional information request and automation. This is more useful than the single bulb in the utility room, as Alexa is in charge of two table lamps which she can turn on/off together or separately and it is easier to use the automation than going from table to table.

One disadvantage here is that Alexa is quite often fooled by the TV. Several times a week she will leap in, trying to answer a question she thinks the TV has asked her. The first times this happen are decidedly spooky... then it just becomes irritating. Still - it is incredible value for what it does.

The Echo Dot is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com

Phillips Hue

Although not part of the Echo system, I ought to say a few words about Hue in its own right. This consists of a central controller linked to you wifi and individual bulbs that are also linked, meaning you can control those bulbs from a smartphone app. The system works well with Echo, but also has some great features standalone. From my phone, I can control the light bulbs in the system, switching any of them on and off or dimming them with a slider. (If I had fancy coloured bulbs, I could also do colours, but I stuck to white.)

By default you can only do this within the house, but if you register with Hue's system, you can also do it remotely via the internet. I find the best part of this extended facility is that it can detect when you are coming home and it's after dusk and will automatically switch selected lights on - so you never come home to a dark house.

We have also installed a Hue wall switch in the utility room, which gives on/off and fade controls for that light. The Hue bulbs we have in table lights are easier to control via the app or an Amazon Echo than manually, but the single bulb in the utility room often seemed harder to deal with that way, so now we have the option to do this manually, without disabling the remote control, which would happen if we used the wall switch.

I don't think I'd ever extend it to the whole house - but it's excellent having this available in our test rooms.

Hue is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com

Is it for me?

I wouldn't get rid of our home automation, and would happily extend it to include, for example, a smart thermostat. We love our main Echo as a music player/hands free radio, but a lot of the extra 'skills' seem more for show than practical purposes. So it's restrained enthusiasm all round.

Here's that video again, attempting to get Alexa to play Schoenberg's Verklärte Nacht:

Published on April 02, 2017 23:51

March 28, 2017

Bye bye to the English pie

Call that a pie? Image from

Google

Recent arguments on the radio about what a 'pie' is have proved very entertaining. Apparently there are those who claim something can only be a pie if it is entirely encased in pastry. They should listen to Lewis Carroll's Humpty Dumpty. The character claims words mean whatever he says they mean. He's not quite right - it's not down to a single arbiter. But words in English certainly do mean whatever they are generally used to mean. And those meanings change. A living language evolves. Try to set it in aspic and it becomes a museum piece.

Call that a pie? Image from

Google

Recent arguments on the radio about what a 'pie' is have proved very entertaining. Apparently there are those who claim something can only be a pie if it is entirely encased in pastry. They should listen to Lewis Carroll's Humpty Dumpty. The character claims words mean whatever he says they mean. He's not quite right - it's not down to a single arbiter. But words in English certainly do mean whatever they are generally used to mean. And those meanings change. A living language evolves. Try to set it in aspic and it becomes a museum piece.Those who argue for the pastry-surrounded pie are confusing language and branding. It's fine to set rules for the official name for a product or brand. But, in English, a pie means whatever people call a pie. Hence our ability to refer unashamedly to shepherd's pie or cottage pie, neither of which have any pastry whatsoever.

When I give talks on writing, I point out a number of 'errors' that are disappearing because the language is evolving. For example, some pedants object to using 'their' when referring to an individual. But the trouble is, the language doesn't have a singular equivalent. So we end up with the clumsy formation 'A student must learn his or her foundation material in the first year.' Before long, 'their' will have entirely replaced 'his or her' - and good riddance.

Similarly, when I talk to scientists they still unanimously think that 'data' is plural. So they insist on saying 'The data are now ready for processing.' The rest of the world has realised that data is a singular collective noun and we should say the far more elegant 'The data is now ready for processing.' Scientists will catch up eventually, but they tend to be conservative, so it will take a while.

Some changes are truly painful to those who have been brought up with the original version. Remember the outcry over the 'appropriation' of 'gay'. I'm sure when 'a norange' started to transition to 'an orange' there was muttering in the streets. And I share the pain over some language changes. Yet in the end, I accept that evolution is an irresistible force and it's better to go with the flow and enjoy the ride.

So all together now, to a tune by Don Maclean:

'Bye bye to the English pie,

If language don't evolve it is going to die...'

Published on March 28, 2017 04:40

March 23, 2017

Never say never... but...

Definitely not electric (image from

Wikipedia

)It was a little eyebrow-raising to see that a company called Wright Electric is claiming that they will have electric planes flying between London and Paris in 10 years. While we genuinely should never say 'never' with technology, I think the probability is so low that it would be well worth betting against it.

Definitely not electric (image from

Wikipedia

)It was a little eyebrow-raising to see that a company called Wright Electric is claiming that they will have electric planes flying between London and Paris in 10 years. While we genuinely should never say 'never' with technology, I think the probability is so low that it would be well worth betting against it.In part, this is a simple competitive edge issue. If the technology existed, it could certainly only cope with short range hops - hence London to Paris. Unfortunately, this is already a highly competitive route because Eurostar offers a far more pleasant journey than flying with similar or better city centre to city centre times. It's not the ideal route to introduce new flight technology on.

Even if London to Paris is attractive, though, this assumes, though that we have coped with 'if the technology existed.' The big problem here is battery technology. I have no doubt at all that batteries will get better in the next few years. But the difficulty faced by a plane, as opposed to a car, is the sheer weight of batteries to provide the same amount of energy as aviation fuel.

Kerosene packs a fearsome amount of energy into a relatively small mass. This is why the 9/11 attack was so devastating - it was the energy in the planes' burning fuel that hugely increased the impact. To get a feel for the difference, kerosene has around 100 times* the usable energy per unit mass as a typical laptop (or car) battery. A plane simply can't afford to carry the extra mass that would be required to be fuelled by batteries. To make the London to Paris electric plane feasible would require at least a 20 times improvement, and quite possibly a 50 times improvement in the energy density available from batteries. This may well happen at some point. But to have it developed on a timescale that allows commercial planes to be using it in 10 years is incredibly unlikely.

I worked for an airline when we were just starting to put computers into planes for cabin management and entertainment. They always ended up being antiquated devices, because the safety requirements for aviation rightly require a long period of being bedded in - typically the tech was at least 5 years old by the time it got into the sky. This means we would need this kind of improvement in just a handful of years to make a ten year horizon viable. So if anyone's up for a bet and will offer decent odds, I'm happy to take it.

This has been a green heretic production

* This figure is about 7 years old, and as battery technology is always advancing it may well be only 90 times by now, but I don't have the latest figures. But batteries haven't changed much in capacity during this period.

Published on March 23, 2017 02:23

March 20, 2017

Review - The China Governess - Margery Allingham

I am a huge fan of Marjory Allingham's Campion books - but even so, I have to say this is probably one to avoid, unless, like me, you want to have read the entire canon. One of Allingham's late contributions, written in the 1960s four decades after the first Campion books, it lacks the joie de vivre of the earlier titles. It's over-long, and very slow - in fact it verges on the dull in places.

I am a huge fan of Marjory Allingham's Campion books - but even so, I have to say this is probably one to avoid, unless, like me, you want to have read the entire canon. One of Allingham's late contributions, written in the 1960s four decades after the first Campion books, it lacks the joie de vivre of the earlier titles. It's over-long, and very slow - in fact it verges on the dull in places.That's not to say it's entirely without interest, but what interest there is remains specialist. It's a sociological museum, with its stiff, emotionally retarded upper-middle class characters, who we are supposed to sympathise with, but who mostly repel. By today's standards it is also horribly un-PC about 'mental defectives'. Some readers will, I suspect, be outraged - but you do have to see this as a fascinating uncovering of just how things were in the early 60s. We tend to look back and think of the sixties as being all hippies and free love and rebellion, but we have to remember this was less than 20 years after the end of the Second World War, and the whole point of what happened in the 60s was a reaction to this establishment stiffness.

Perhaps most fascinating is the reaction of older family members to a historical black sheep in their family. Where in the current TV show Who Do You Think You Are there is a kind of horrified delight at, say, finding a murderer in the family's past, here it causes genuine pain and anger. The family's way of dealing with unpleasant things is to pretend they don't exist. Sadly, though Campion does act as a kind of operational fairy godmother to make things happen (eventually), we see very little opportunity for his usual skills - and Lugg is sadly extremely underused.

So, definitely not a book to read as an introduction to Campion - only worth going for if you do want to see just how uptight and sad the upper-middle class was in the early 1960s.

The China Governess is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com

Published on March 20, 2017 02:40

March 14, 2017

Is dark matter disappearing altogether?

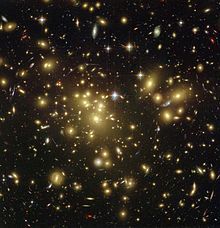

A few days ago at a talk, I mentioned in passing that in a few years' time we may no longer think that dark matter exists. (In the unlikely event you've not heard of it, dark matter is a hypothetical kind of stuff that only interacts with ordinary matter through gravity, which is thought to exist because large collections of matter, such as galaxies act as if they have more matter in them than they should have.)

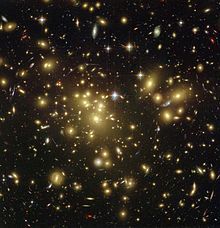

A galactic cluster that provides more

A galactic cluster that provides more

gravitational lensing that its ordinary matter

predicts. (Image from Hubble via Wikipedia )After the talk, a handful of teenage physics enthusiasts collared me and said 'Surely you don't think dark matter doesn't exist?' After asking them not to call me Shirley, I admitted I was a dark matter sceptic. But I felt their pain. When I was their age, the steady state theory of cosmology was still an accepted challenger to the big bang, but its star was fading fast. I preferred steady state in part because it seemed to be a more elegant theory and in part because one of its originators was my teenage physics hero, the remarkable Fred Hoyle. I was genuinely upset when steady state was pushed out of consideration. Science may be objective, but it doesn't stop us from having emotional attachments.

I'd say for the first time since it became widely acknowledged, dark matter is in danger of being replaced as the best accepted theory within a decade. There has been one challenger for a while in the form of MOND (Modified Newtonian Dynamics), but critics are quick to point out it doesn't explain all the phenomena ascribed to dark matter. (To be fair dark matter isn't 100 per cent either, but that's by the by.) However, there are now at least two other alternatives that explain the behaviour of large collections of matter to some degree without the need for a new type of stuff.

One suggestion is painfully simple - it takes a microscope to those innocent words in the first paragraph 'should have'. The existence of dark matter is based on guestimate of the amount of conventional matter in galaxies and other large collections of space stuff. It is, without doubt, a good guestimate, based on best current knowledge. But the reality is that the calculation has to involve estimation based in part on theory, and that leaves room for error. It only takes a small correction to make dark matter disappear. Again, there are of holes left by making this assumption, but it's a potential line of thought.

The second suggestion is a lot more sophisticated (so some theoreticians may prefer it). The concept of emergent gravity, where gravity is somewhat like thermodynamics in emerging from statistical behaviour, rather than being a true underlying fundamental force, has been put forward by some as a way of providing a mechanism to do away with dark matter. As this semi-technical article by Sabine Hossenfelder shows, there are still significant problems for this explanation, but it is without doubt another strand.

At the moment, then, nothing has knocked dark matter from its 'best accepted theory' perch. But it has never been so strongly challenged. We always need to remember that science is not about black and white, absolute fact, but establishing the best theory we can given the current evidence. Dark matter could recover from its wobble, just as the big bang did with modifications that brought it into line with current data. But there is no doubt that we exist in cosmological (and particle theory) interesting times.

A galactic cluster that provides more

A galactic cluster that provides moregravitational lensing that its ordinary matter

predicts. (Image from Hubble via Wikipedia )After the talk, a handful of teenage physics enthusiasts collared me and said 'Surely you don't think dark matter doesn't exist?' After asking them not to call me Shirley, I admitted I was a dark matter sceptic. But I felt their pain. When I was their age, the steady state theory of cosmology was still an accepted challenger to the big bang, but its star was fading fast. I preferred steady state in part because it seemed to be a more elegant theory and in part because one of its originators was my teenage physics hero, the remarkable Fred Hoyle. I was genuinely upset when steady state was pushed out of consideration. Science may be objective, but it doesn't stop us from having emotional attachments.

I'd say for the first time since it became widely acknowledged, dark matter is in danger of being replaced as the best accepted theory within a decade. There has been one challenger for a while in the form of MOND (Modified Newtonian Dynamics), but critics are quick to point out it doesn't explain all the phenomena ascribed to dark matter. (To be fair dark matter isn't 100 per cent either, but that's by the by.) However, there are now at least two other alternatives that explain the behaviour of large collections of matter to some degree without the need for a new type of stuff.

One suggestion is painfully simple - it takes a microscope to those innocent words in the first paragraph 'should have'. The existence of dark matter is based on guestimate of the amount of conventional matter in galaxies and other large collections of space stuff. It is, without doubt, a good guestimate, based on best current knowledge. But the reality is that the calculation has to involve estimation based in part on theory, and that leaves room for error. It only takes a small correction to make dark matter disappear. Again, there are of holes left by making this assumption, but it's a potential line of thought.

The second suggestion is a lot more sophisticated (so some theoreticians may prefer it). The concept of emergent gravity, where gravity is somewhat like thermodynamics in emerging from statistical behaviour, rather than being a true underlying fundamental force, has been put forward by some as a way of providing a mechanism to do away with dark matter. As this semi-technical article by Sabine Hossenfelder shows, there are still significant problems for this explanation, but it is without doubt another strand.

At the moment, then, nothing has knocked dark matter from its 'best accepted theory' perch. But it has never been so strongly challenged. We always need to remember that science is not about black and white, absolute fact, but establishing the best theory we can given the current evidence. Dark matter could recover from its wobble, just as the big bang did with modifications that brought it into line with current data. But there is no doubt that we exist in cosmological (and particle theory) interesting times.

Published on March 14, 2017 03:03

March 13, 2017

Poor Pret

Image from

Wikipedia

I always find it amusing when the bosses of large companies demonstrate an impressive lack of understanding of market forces. A few days ago, the HR director of sandwich/coffee chain Pret a Manger told a parliamentary committee 'I would say one in 50 people who apply to our company are British', citing this as a reason they need to continue having access to cheap foreign labour. She also said that she didn't think pay was an issue, despite a starting package of around £16,000 in London, as after a few years you could earn a lot more.

Image from

Wikipedia

I always find it amusing when the bosses of large companies demonstrate an impressive lack of understanding of market forces. A few days ago, the HR director of sandwich/coffee chain Pret a Manger told a parliamentary committee 'I would say one in 50 people who apply to our company are British', citing this as a reason they need to continue having access to cheap foreign labour. She also said that she didn't think pay was an issue, despite a starting package of around £16,000 in London, as after a few years you could earn a lot more.Picking this apart, I've a few issues with this argument. I don't have any evidence for that 'I would say one in 50' (don't you find 'I would say' suspiciously vague?) - is it true at all? Is it only true of central London stores? Or is that a countrywide average? Without data it's impossible to say. But let's take it at face value. What the market is really saying is that the rewards aren't good enough for the job, and they can only maintain that £16,000 starting salary (resulting in £84 million profit in their results for 2015) by employing people for whom an amount it's difficult to live on in any expensive location seems a lot of money because they come from a country where that is a large pay packet (or they're doing the job for other reasons, such as learning a language).

If the supply of cheap labour dried up there's a simple solution. You put up your starting salary until you do get enough people applying. If you have to put it up so much that you don't make a profit, you don't have a viable business model. That's what market forces are about.

Companies like Pret have had it easy to date, because they operate in a 'pile it high, sell it expensive' market. Their staff costs per head are low, but they sell premium products (i.e. ones where a small increase in cost results in a considerable increase in price). The world is changing, and poor Pret feels sorry for itself. I'm afraid I can't join in the sobbing.

Published on March 13, 2017 02:56

March 7, 2017

Learn from history, don't delete it

Colston Hall (image from

Wikipedia

)I'm coming towards the end of two years spending two days a week working at Bristol University. I've had a wonderful time, and have come to love this little gem of a city, getting to know it far better than I did before. One thing that has become obvious is the way that some Bristolians are torn apart by their heritage. Because this is a city that was, to some degree, built on two trades that are now abhorrent - the slave trade and tobacco.

Colston Hall (image from

Wikipedia

)I'm coming towards the end of two years spending two days a week working at Bristol University. I've had a wonderful time, and have come to love this little gem of a city, getting to know it far better than I did before. One thing that has become obvious is the way that some Bristolians are torn apart by their heritage. Because this is a city that was, to some degree, built on two trades that are now abhorrent - the slave trade and tobacco.As you go around the city, there are names you often encounter: Colston and Wills. The first refers to Edward Colston, a prominent slave trader and the Wills dynasty was behind the eponymous tobacco company, now part of Imperial Tobacco. Such is the negative feeling that there is currently

You don't make the past go away by hiding it - but you can prevent lessons being learned by doing so. History is fundamentally important: I wish it got more priority in schools. There's a reason that Auschwitz was not obliterated. The past should not be forgotten.

There is, of course, a big difference in feel between a former concentration camp and a building that apparently glorifies someone once involved in an occupation that we now despise. However, I don't think it would be right for Bristol to attempt to sanitise itself this way. It's an action driven by guilt, and guilt for something that happened in your city's past is a waste of energy. Instead, I suggest this should be turned into something positive. We shouldn't be petitioning for Colston and Wills to be forgotten. It would be far better if the city insisted that major buildings bearing such names should be required to have a prominent, permanent exhibition explaining where the money came from, and at what cost.

That's what history is for. Not something to feel guilty about, apologise for and then attempt to erase. It should be brought out, made very visible and used to learn lessons for the future.

Published on March 07, 2017 01:42

March 6, 2017

Why it isn't easy being green

Yes, please, if Tesla would like to give me one

Yes, please, if Tesla would like to give me one(Image from Wikipedia )As someone with real concern for the environment, I am convinced that electric cars are the future, and the sooner we can get rid of petrol and diesel, the better. When I was younger, my fantasy car was an Aston Martin - now it's a Tesla.

However, as an official green heretic, I have to point out that, like almost all environmental decisions, it's a bit more complex than it first appears. We need to apply logic as well as emotion. Electric cars (and trains, for that matter) are great in terms of emissions - provided they use electricity that itself is produced in an environmentally friendly fashion. It has been pointed out that in Germany, which has an aggressive 'get rid of petrol cars by 2030' policy, there could be a resultant increase in carbon emissions.

The trouble is that Germany is pretty well incapable of being totally green in its electricity production by 2030, because of its irrational decision to close its nuclear power plants. What about wind and solar? They're coming on - but nowhere near fast enough. In fact, Germany has had to slow down its wind expansion because the existing wind supply is already proving disruptive to the grid because of its irregularity. The more you depend on wind, and to an extent solar, the greater need there is for supply that can be switched in quickly to cover troughs in generation.

As a result of the short-sightedness of their supply policy, if Germany does achieve 100 per cent electric cars by 2030 its carbon emissions will go up, due to the extra emissions from the dirty generation that will need to be used to support it.

I am not saying they should hold back on the electric vehicles - on the contrary, I hope we take a similar view of pushing the move to electric vehicles in the UK. (And reversing the terrible decision to cut short the electrification of GWR's trains before reaching Bristol Temple Meads.) But such a policy needs to go hand-in-hand with a transfer of generation to non-emitting sources - which at the moment almost certainly means having more nuclear in the mix as well as more wind and solar.

Published on March 06, 2017 01:42