Clifford Garstang's Blog, page 79

June 3, 2013

Audio of a Live Interview with Me

One of the oddest things about publishing and promoting a book is giving interviews. I’ve given several over the course of the last four years, since the appearance of my first book in 2009. Usually they have involved an exchange of emails or in any event written responses to written questions. In November 2012, however, I was invited to be interviewed in front of a live audience at WriterHouse, a wonderful community organization for writers in Charlottesville, Virginia.

One of the oddest things about publishing and promoting a book is giving interviews. I’ve given several over the course of the last four years, since the appearance of my first book in 2009. Usually they have involved an exchange of emails or in any event written responses to written questions. In November 2012, however, I was invited to be interviewed in front of a live audience at WriterHouse, a wonderful community organization for writers in Charlottesville, Virginia.

I was a little nervous about the event, partly because it was live but partly because at that point I had heard very little reaction to my book, positive or otherwise. I didn’t know what the interviewer might ask or whether she would even like the book, which could have made for a very awkward experience.

But Katherine McNamara asked wonderfully perceptive questions, and I thoroughly enjoyed the experience of attempting to give answers that did justice to the questions. And WriterHouse was kind enough to record the event and post a podcast of it.

I would love it if you would give it a listen: Katherine McNamara interviews Clifford Garstang

May 29, 2013

2013 Reading: Cimarron Rose by James Lee Burke

Cimarron Rose (Billy Bob Holland) by James Lee Burke isn’t a book you should read for the writing. The story is compelling, if only because the reader will want to know just HOW the bad guys meet their gruesome ends and how the good guys will be exonerated. (Also, having read another Burke, I guess the reader wants to know just what wounds the hero will suffer that will impact his performance in the next book.)

Cimarron Rose (Billy Bob Holland) by James Lee Burke isn’t a book you should read for the writing. The story is compelling, if only because the reader will want to know just HOW the bad guys meet their gruesome ends and how the good guys will be exonerated. (Also, having read another Burke, I guess the reader wants to know just what wounds the hero will suffer that will impact his performance in the next book.)

The good guy here–good guy, even with his flaw of a violent temper–is Billy Bob Holland, a former Texas Ranger now turned defense attorney (except that he won’t take drug trafficking cases). He’s the lawyer for Lucas Smothers, a kid accused of murder. Lucas just happens to be Billy Bob’s illegitimate son, which is the town’s worst-kept secret. But Lucas and Billy Bob have enemies, so it’s not easy . . .

Ugh. Lots of flat characters and one cliche after another. I can’t recommend the book, but I keep reading things like this to see if I can learn anything about plot.

Cimarron Rose (Billy Bob Holland) by James Lee Burke isn’...

Cimarron Rose (Billy Bob Holland) by James Lee Burke isn’t a book you should read for the writing. The story is compelling, if only because the reader will want to know just HOW the bad guys meet their gruesome ends and how the good guys will be exonerated. (Also, having read another Burke, I guess the reader wants to know just what wounds the hero will suffer that will impact his performance in the next book.)

Cimarron Rose (Billy Bob Holland) by James Lee Burke isn’t a book you should read for the writing. The story is compelling, if only because the reader will want to know just HOW the bad guys meet their gruesome ends and how the good guys will be exonerated. (Also, having read another Burke, I guess the reader wants to know just what wounds the hero will suffer that will impact his performance in the next book.)

The good guy here–good guy, even with his flaw of a violent temper–is Billy Bob Holland, a former Texas Ranger now turned defense attorney (except that he won’t take drug trafficking cases). He’s the lawyer for Lucas Smothers, a kid accused of murder. Lucas just happens to be Billy Bob’s illegitimate son, which is the town’s worst-kept secret. But Lucas and Billy Bob have enemies, so it’s not easy . . .

Ugh. Lots of flat characters and one cliche after another. I can’t recommend the book, but I keep reading things like this to see if I can learn anything about plot.

May 28, 2013

Tips for Writers: Talk to People

This isn’t a writing tip, exactly. It’s more of a marketing tip, and one that I expect many writers will find hard to follow. But here it is: talk to people.

This isn’t a writing tip, exactly. It’s more of a marketing tip, and one that I expect many writers will find hard to follow. But here it is: talk to people.

What? Me? I’m an introvert. I can’t talk to people!

Sure you can. I went to an art fair this weekend. Our local community art center has an annual event called Art in the Park, which draws exhibitors from all over the region displaying paintings, photographs, sculpture, and various crafts such as ceramics, woodwork, and jewelry. This year the weather was fantastic and it looked like there was a big crowd. I browsed all the booths. At many, the artist was either absent or was sitting in a chair at the back of the booth, or even outside the booth. Some of the artists nodded and smiled or said hello, and let me browse unmolested. From the browser’s point of view, that was great.

But in one booth, the artist greeted me, said his name, and offered his hand to shake. He asked my name and a pertinent question or two. Then he guided me toward one of his items and suggested I might like it. Another potential customer came in and he repeated that tactic with him, then returned to me with an apology. I browsed a bit more, we chatted, and I bought something. That’s right–his pitch worked on me!

Possibly the artist was just being friendly, and maybe he’s always friendly. But I bet he sells more by being friendly than he would if he just sat in his chair and waited for a customer to pull out his wallet.

I’ve noticed the same thing in bookfairs. The authors who just sit back and wait for buyers to walk up and engage them are missing out. And this applies in bookstores and other venues where you’re doing a signing. You have to be out front, engaging with the buyers. As much as you want to be just a writer, there’s no getting around the fact that you’re also a salesperson. Grouchy doesn’t sell. Friendly does.

May 27, 2013

The New Yorker: “We Didn’t Like Him” by Akhil Sharma

June 3, 2013: “We Didn’t Like Him” by Akhil Sharma

June 3, 2013: “We Didn’t Like Him” by Akhil Sharma

In the Q&A with Akhil Sharma we learn that this story was meant to mock a real person who, apparently, offended the author for the way he behaved at a funeral. (Although Sharma doesn’t know the fellow’s name, someone really should go to India and find him, and maybe sue Sharma? What an absurd thing to say to the New Yorker. Isn’t it?)

Anyway, the story is a little odd for other reasons. The narrator is a kid—8 when the story begins—who is watching his cousin Manshu, about 6 years his elder. Manshu’s father is dead and then his mother dies, and Manshu moves in with an uncle. But he spends most of his time at the local temple, which he eventually takes over as the temple pandit (or pundit, as the New Yorker uses in the Q&A). Manshu marries outside of his caste, to the consternation of the local people, including the narrator’s father. When the narrator’s father dies, Manshu behaves oddly. Among other things, he takes a cell phone call during the rites. Much later, when Manshu’s wife dies, the narrator is compelled to help him arrange the funeral, even assisting—against custom and to his horror—with the spreading of the woman’s ashes in the river.

The story, then, is about death and about the rituals we follow in honoring the dead. The narrator is offended by Manshu, but Manshu says he is being modern by introducing the idea and a eulogy into a Hindu funeral. And who cares if he answers his cellphone. Similarly, what difference does it make who scatters the ashes in the river? I suppose that’s really what the story is suggesting.

Any other thoughts?

May 21, 2013

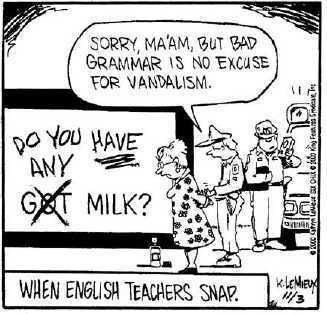

Tips for Writers: Use Sentence Fragments Sparingly

I had been reading a draft story by a young writer who had fallen into a pattern of using sentence fragments. It was a stylistic tic that drew attention to itself. On closer examination, I realized that the fragments mostly omitted the verb “to be,” the most overused verb in lazy writing. It was as if the writer had chosen to use the fragment in order to avoid “to be,” rather than rewriting the sentence with a dynamic verb. This led me to post on Facebook, in a moment of frustration, the following status update: “Fragments are cop-outs. Afraid to pick a verb? Use a fragment! Blecch.”

I had been reading a draft story by a young writer who had fallen into a pattern of using sentence fragments. It was a stylistic tic that drew attention to itself. On closer examination, I realized that the fragments mostly omitted the verb “to be,” the most overused verb in lazy writing. It was as if the writer had chosen to use the fragment in order to avoid “to be,” rather than rewriting the sentence with a dynamic verb. This led me to post on Facebook, in a moment of frustration, the following status update: “Fragments are cop-outs. Afraid to pick a verb? Use a fragment! Blecch.”

Most people responded with humor, some with questions. I realized that I had not specified in my update that I was talking about fiction, and I had failed to qualify my statement. So I added that, obviously, fragments had a place in good fiction, but that they’re often overused. One friend, who chose to ignore my qualifying comment, argued with me. (I’m not sure he quite understands what Facebook status updates are about, but that’s an argument for another day.)

But I’ll stand by my point. Fragments are often a sign of lazy writing. They can distract the reader, and they’re often masking a passive voice–typically the verb “to be.”

Grammar Girl elaborates and makes my basic point: On sentence fragments. Note this comment in particular: “Sentence fragments in fiction can be a useful way of conveying pace, tone, and intensity. However, overuse can lead to lazy writing – fragments should be used sparingly, and for a good storytelling purpose.”

Book Giveaway: The Forty Rules of Love by Elif Shafak

I confess that I haven’t yet read this book, but I read Shafak’s previous book, The Bastard of Istanbul, which was excellent. Here’s the description of The Forty Rules of Love:

I confess that I haven’t yet read this book, but I read Shafak’s previous book, The Bastard of Istanbul, which was excellent. Here’s the description of The Forty Rules of Love:

A mesmerizing tale of love-from the author of The Bastard of Istanbul

Elif Shafak, the most widely read female writer in Turkey, has earned a growing fan base all over the world with her bestselling The Bastard of Istanbul. In The Forty Rules of Love, her lyrical, imaginative new novel about the famous Sufi mystic Rumi, Shafak effortlessly blends East and West, past and present, to create a dramatic, compelling, and exuberant tale about how love works in the world. Shafak unfolds two parallel narratives-one set in the thirteenth century, when Rumi encountered his spiritual mentor, the wandering dervish known as Shams of Tabriz, and one contemporary, as an unhappy American housewife, inspired by Rumi’s message of love, finds the courage to transform her life.

Anyway, I’ve got an extra copy of the book to give away. All you have to do to win is leave a comment on this blog post AND be sure you are on my email list. Go here to sign up. (If you have trouble, it probably means you’re already on the list.) I’ll select ONE winner on May 31.

May 20, 2013

The New Yorker: “Thirteen Wives” by Steven Millhauser

May 27, 2013: “Thirteen Wives” by Steven Millhauser

May 27, 2013: “Thirteen Wives” by Steven Millhauser

I’m not sure I get this story, which you can read in its entirety for free. Go do that now: “Thirteen Wives.”

Here’s the gist of it. The speaker says he lives in a sprawling house and each of his thirteen wives has her own room. He then proceeds to describe each of the wives—listed by number, not name—and his relationship with her. All the wives are quite different; in fact, they seem to cover the universe of possible personality types, as if his wives represent all women. In contrast, we know very little about the personality of the man, except as he compares himself to each of the wives. But he is not every man—he is one man. Who, then, are the women?

As I read through all the different wives, I wondered if the narrator weren’t speaking really of just one woman, with moods or a split personality. (It’s not clear how they could play cards in small groups, as the narrator says they do, if that were the case.) It might be that the wives represent the same wife at different ages. In fact, wife number 10 is sick, and wife number 12 is a “negative woman,” as if she were really an absence, rather than a presence. And number 13 is his memory of women. He says, “ The incessant changefulness of my thirteenth wife may, of course, arise from something deceptive in her nature, as if she’s continually casting up new images in an effort to evade responsibility for any one of them,” which suggests that she is all the previous wives put together.

Millhauser is known for such slightly off-kilter, perplexing stories. As of this writing, there’s no Q&A with the author to help us with this one. So, what’s your take? Do you find this a sexist story?

May 18, 2013

2013 Reading: Damascus Gate by Robert Stone

DAMASCUS GATE.

DAMASCUS GATE. by Robert Stone

by Robert Stone

I confess that I’ve only read one other novel by Robert Stone, and I have to say I didn’t care much for Bay of Souls: A Novel. I really need to read his acclaimed earlier novels like A Flag for Sunrise.

But Damascus Gate is quite impressive. There were things about it I didn’t like–the romance seemed forced, for example, although it’s critical to the plot–and things I didn’t understand–much of the history of religion is simply beyond my previous reading–but it still held my attention.

Christopher Lucas is an American journalist in Israel. He’s adrift, both professionally and spiritually, and when he encounters seekers of various persuasions he lets his curiosity get the better of him. That and his heart, because he’s immediately attracted to Sonia, an American activist/jazz singer/Sufi. Sonia becomes involved with something of a growing cult, and both interact with various groups that have dark, secret motives that are gradually disclosed.

Fascinating stuff.

2013 Reading: River of Dust by Virginia Pye

River of Dust: A Novel by Virginia Pye

River of Dust: A Novel by Virginia Pye

I’d really been looking forward to reading this novel because the author is a friend of mine. Besides that, though, it’s set in China, which I know something about.

I thoroughly enjoyed the read. As it turns out, the setting of the book was more unfamiliar to me than I expected. First, the time is 1910, just before the fall of the Empire, and the story revolves around missionaries in Shanxi Province, a milieu that I had not previously explored.

The setting is extremely important because Shanxi is the site of the massacre of missionaries that occurred during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, an event that weighs heavily on the foreigners who have returned to the area a decade later to resume their missionary work. It’s a dry, dusty time—drought and famine have taken their toll. Some welcome the foreign faith as a way out of their misery; others resent it and cling to their old ways.

Into this environment come the Reverend and his pregnant wife Grace, and their two servants Ahcho (who has embraced Christianity) and Mai Lin (who follows the old ways, whatever she professes outwardly). In the first chapter, the missionary couple’s young son is kidnapped by Mongolian raiders. The book then, details the Reverend’s search for the boy and his encounters with various villagers, nomads, and opium smokers. Meanwhile Grace is ill and struggles with her pregnancy, and their servants just have to shake their heads and wonder what drives these foreigners.

The writing is beautiful and the issues raised—arrogance of the West, the clash of cultures, powerlessness and faith—are thought provoking.