Clifford Garstang's Blog, page 72

September 4, 2013

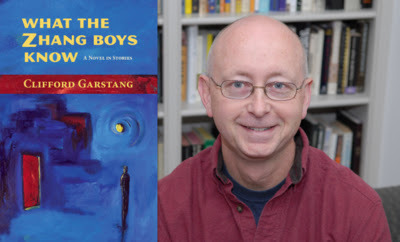

Reading and Discussion Guide for What the Zhang Boys Know

What the Zhang Boys Know is an ideal choice for your bookclub or classroom discussion because of the range of voices and themes it presents. I would be delighted to join such a discussion either in person, if possible, or by Skype. Visit the Contact page of this website for more information.

What the Zhang Boys Know is an ideal choice for your bookclub or classroom discussion because of the range of voices and themes it presents. I would be delighted to join such a discussion either in person, if possible, or by Skype. Visit the Contact page of this website for more information.

Reading and Discussion Guide for What the Zhang Boys Know

These questions are suitable for guiding book club or classroom discussion. Your feedback and additional questions are welcome at info@cliffordgarstang.com.

This book is called a “novel in stories.” What distinguishes the book from a typical novel? How is it different from typical story collections?

Before the book begins, Zhang Feng-qi is faced with the tragic death of his wife, and now he must find a way to raise his two young sons and cope with his own grief. How do people generally react when dealing with loss of this magnitude? Is Zhang’s behavior rational? Is it possibly rooted in his culture?

Nanking Mansion, the condominium building in which the book takes place, is home to several artists and writers. What role does art play in the book? What are the different ways that characters react to art? What is your own experience with interpretation of art, either created by yourself or others?

Like the city itself, the condominium building is home to a diverse cast of characters. How is diversity manifested? What is the significance of that diversity? Which of the stories address diversity explicitly, and in what ways?

Besides the fact that all these characters live in the same building, what else connects them?

In what ways is the novelist in the story “The Nations of Witness” an outsider? How would you describe his role in the book? In what ways is he likable or unlikable? How does the story relate to the larger story of the novel? What other characters are outsiders?

What do the Zhang Boys know? Is the title of the book just whimsical? Or does it have some greater significance? In what ways do the boys help tie the stories together?

Many of the stories in the book deal in one way or another with strained family relationships. In what way do these relationships inform the overall narrative of the book? Do these conflicts make it easier or more difficult for the reader to relate to the characters?

Loss and grief are important elements of the book, but the characters express their grief in many different ways. What are some of the ways grief is shown?

The landscape of the city is often drab and uncompromising, but beauty still manages to arise inside and out. In what ways do the characters experience and engage with the natural world?

Click here for downloadable pdf of this discussion guide:

Reading and Discussion Guide for What the Zhang Boys Know

Interview with Tom Lombardo, author of What Bends Us Blue

A few days ago, I posted my brief review of a wonderful collection of poems by my friend Tom Lombardo: What Bends Us Blue. Tom also agreed to answer some questions, which I’m happy to share with you here.

A few days ago, I posted my brief review of a wonderful collection of poems by my friend Tom Lombardo: What Bends Us Blue. Tom also agreed to answer some questions, which I’m happy to share with you here.

Q&A with Tom Lombardo

Cliff Garstang: Congratulations on the publication of What Bends Us Blue. The book is your “debut” collection of poetry, which surprises me. I’ve seen your work in print for so long and have known you as an editor (of After Shocks, which we’ll talk about in a bit, and at Press 53) that it seems as though you must have had a book out already. How does it feel to be a “debut” poet?

Tom Lombardo: I guess I would say “relieved” finally to have a full-length collection published after years of submitting it to publishers and contests ad nauseum. I had literally given up on this collection. But April Ossmann, who had worked with me editing What Bends Us Blue, suggested WordTech, and I always do what April tells me to do, so I sent it, thinking that this was the final submission before its death, but LO! It was accepted! I’d had a chapbook published back in 1998, and then my anthology After Shocks: The Poetry of Recovery for Life Shattering Events in 2007. I have another chapbook accepted for publication in 2014. I’ve also published scores of poems in the U.S., the U.K., Canada, and India, and I’m the Poetry Series Editor for Press 53 (Winston-Salem), so I’ve been a poet and poetry editor for quite some time. But publishing this full-length collection is quite satisfying.

CG: From the beginning of the book, the reader gets that you’re exploring the blues in all of the connotations of the word. Let’s start with music. What’s your connection to music and how does it influence your poetry?

TL: When I was in 7th grade, Sister Mary Flora (aka Elizabeth Farnsworth, God rest her soul) took me aside and handed me a tenor recorder and started my lessons. She did that for two reasons: I had the largest hands in the class (the tenor recover is two-feet long), and I had some behavior issues and this was her way of focusing me. There were two other boys in the class who already played recorders—a soprano and an alto. Sister Mary Flora composed original scores for the three of us to accompany the school choir. We performed Gregorian chant, in Latin, using the 4-line Gregorian clef, not the treble clef that you normally see on sheet music. Sister composed on her harpsichord, so we were an authentic Medieval ensemble. We won competitions all over the state of Pennsylvania. That woman had vision. She was demanding, but the experience was rewarding, and it started me playing music.

When I was in high school, I played in my first rock-and-roll band. Lead singer and tambourine. Covered the hits of the 1960s. In my 20s, I picked up a harmonica one day to jam with friends, and I fell in love with it. I’ve been playing it since then. I’ve played in probably a dozen garage bands over that time. I love performing. I was once in a Jazz-Blues trio that played regular paying Saturday night gigs in a popular club in Knoxville. I’ve played at festivals here and there. I’ve played to fairly large crowds and I’ve also played in barbeque joints and hotel lounges where only 5 people were in the audience. I’ve loved every minute of it. And here’s one thing I’ve learned over all those years playing in bands: No matter how good the musicians, your band can never be better than its drummer. Remember that.

Informally, I will jam with anyone in any genre: blues, rock, bluegrass, soul, R&B, reggae, Old Time Appalachian. I can usually adapt to any style. I carry an 8-set of harps with me where ever I go, and I’m always looking for musicians to jam with. Harmonica is essentially a rhythm instrument, so it’s pretty easy to fit in once you catch the rhythm. And when I hit the licks just right, my whole body vibrates. Like getting that line of poetry exactly right. You can feel it from soles to scalp.

Being a musician—even mostly as an amateur—has influenced my poetry craft in the observance of rhythm. The rhythms of music—whether a 12-bar a-b-a blues/rock progression or a 32-bar a-a-b-b Old Time Appalachian progression or some of the nonstandard jazz progressions—are precise, but they leave room for freedom, improvisation, as long as you keep the underlying rhythm intact and close it out on the right beat. Lines and stanzas of poetry have rhythms, too, even in free verse. I believe that being a musician has taught me how to view the rhythms of diction, syntax and lines in a way that make the rhythms of the poem fit its mood or emotion. I wish I could say that this is not hard work, that it comes naturally, but no. It comes in revision, revision, revision. When you read What Bends Us Blue, closely examine some of my diction and syntax choices. Many of those units are selected for their rhythms—how they fit the rhythm of the line or the stanza or the poem as a whole. And in turn that effort drives me to select diction and syntax that might be unexpected—which I believe helps my poetry. Remember what I said above about the band never being better than its drummer? Well, in poetry, your poems can never be better than your rhythms. Your rhythms are the floor, just like in a band. Musicians build upon the floor of the rhythm section. Poetry should pay attention to its floor.

CG: And then there are “the blues” as in depression, which also finds its way into your work. What about depression inspires you?

TL: I do not suffer from depression. If I did, perhaps I’d be a better poet. Robert Lowell comes to mind. Sylvia Plath. Anne Sexton. Many others. Mental illness has inspired many poets and writers. I do not suffer from a diagnosed mental illness—that I know of—at this time. Maybe there’s hope for something in the future? When I was in college and just afterwards, I spent years depressed and anxious, exhibiting anti-social behaviors (worse than those elementary school days). When I look back on those years—with the medical knowledge I have now—I realize that I suffered post-concussion syndrome from numerous concussions while playing high school and college football for 8 years. One or two concussions per year. More if you count what my coaches called “getting your bell rung.” It ruined my life from the ages of 18-24, when my brain finally came back into focus. I have written a chapbook of poems about it—entitled The Name of This Game—Poems about football and concussions? Fortunately one editor, Sammy Greenspan of Kattywompus Press in Ohio understood it and picked it up for publication in 2014.

In my career as a medical editor, I’ve studied the drugs that are used to treat diseases, and the anti-depressants that are universally prescribed nowadays in lieu of psychological therapy. That’s what inspired my poem entitled “The Poet Chooses His Drug.” We live in a pharmaceutical society. Better living through drugs. There are now 6-7 prescription drugs that treat depression. Which to use? That’s the point of my poem “The Poet Chooses His Drug.” How would a poet choose? The anti-depressants do work, and those who suffer from depression find relief, so I cannot criticize them. But there’s always a risk or a side-effect. Would we have Robert Lowell’s or Sylvia Plath’s work if they’d had Prozac? May have been better for them, but worse for poetry.

CG: The poet Steven Cramer writes in the foreword to your book that What Bends Us Blue is “so deep and wide with feeling it’s fair to say the reader plunges into an emotional element that’s oceanic.” Tell us more about that “emotional element.” The poems seem very personal, but there’s more to it than that.

TL: Yes, the poems in What Bends Us Blue are rooted in personal experience. But poetry is never the literal truth. Poetry must use figurations—metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, irony, strong imagery, intense use of the senses—to reveal A TRUTH about the human condition. I believe that the figurations of authentic poetry create those emotional elements. If I may use one example from What Bends Us Blue. The poem “When” a long, streaming poem about the hours I spent in the hospital the day my wife Lana died in a car wreck. Rooted in personal experience. Emotional elements. But the figurations make it emotionally expressive and evocative, as poetry critic Harold Bloom might say. I used these lines to describe the moments I spent with her lifeless, mangled body:

you notice her

freckles turned off when you look

into her open eyes

her emerald irises replaced by

pupils the size of Buffalo nickels and

a depression

pushed against her left eye socket

a child’s thumbprint on a ball of Silly Putty

when you wonder whether it might be

fixed you ask

nurse fellini is she dead you hear

I’m afraid

so and your wife confirms it

a single red bubble

trickles from the edge of her left eye

through a child’s thumbprint

into her strawblond hair when you think

she’s crying blood you fall

through her black pupils

Note the figurations and imagery: freckles turned off…pupils the size of Buffalo nickels…child’s thumbprint on a ball of Silly Putty…a single red bubble [confirms it]…[trickling] through a child’s thumbprint…crying blood…fall through her black pupils. It’s the figurations that drive up the emotional stakes. In addition, the form of this poem…no punctuation and lines all over the place, curiously enjambed, create a state of unreality or shock, which is the state I was in at the time. Yes, the material is emotionally charged to begin with, but without the imagery and figurations, it’s nowhere near as powerful. That’s what Steven Cramer perceived. Oceans of figurations.

As you might imagine, that poem was extraordinarily difficult to write. Initially, it was inspired by Donald Hall’s poem “Without” which appears in his collection of the same title, about the illness and death of his wife, the poet Jane Kenyon. “When” started out flush left, like Hall’s, with anaphora of the subordinate conjunction “when,” as Hall uses the preposition “without.” But it eventually found its form, which may look like no form at all, but believe me, it’s quite purposely planned to look the way it does on the page. The form along with the figurations and the mixture of second and first person—it meant to disorient the reader. I don’t believe I could have written “When” any sooner than I did, 15 years after Lana’s death. In the writing, I picked off the scab of my grief and let the pus drain. Day after day of writing and revising this poem drove me to through grief to exhaustion.

CG: The book includes the poem “How Bill Gates Saved My Marriage,” one of my favorites of yours, having heard you read it years ago. True story? Or is there anything you’d like readers to know about it?

TL: Let me first note for your readers that What Bends Us Blue contains a balance of emotions, even humor, and this poem is a fine example. “How Bill Gates Saved My Marriage” is based on truth. Yes, indeed, I tracked my wife’s menstrual cycles on Outlook, keeping an eye toward PMS-driven moodiness, so that I might be extra nice or at least avoid anything that might be construed as critical or, God Forbid, confrontational. But the flaw I discovered, as the poem says, “testy engineers / programmed precisely perfect / 28-day cycles. Real-life biology instigates disaster / like the time…” In a poem like this, I ran the risk of offending women, so I was very careful not to be overly critical or sarcastic. PMS after all is a natural part of human biology. So the poem is matter-of-factly humorous and turns out to be, at its core, a love poem. The poet Cathy Smith Bowers, a mentor of mine, calls it “an insightful—and cautiously respectful—take on the phenomenon of PMS.” I respect my wife’s body and thus her PMS. At readings, women come up afterwards to tell me how much they like the poem. One woman told me amazingly that her boyfriend does exactly the same thing with Outlook. Perhaps it’s a trend? A movement? If we respect our mates enough to track their moods, then maybe relationships may be saved. What are relationships if not the accommodation and compromises built upon love, and the learning that comes with them?

CG: You’re the editor of a remarkable book of poems, After Shocks: The Poetry of Recovery for Life Shattering Events. Explain what that is and how it seems to have taken on a life of its own.

TL: After Shocks: The Poetry of Recovery for Life-Shattering Events is an anthology of 152 poems by 115 poets from 15 nations. These poets from around the world present poems of recovery from Grief, War, Exile, Divorce, Abuse, Bigotry, Illness, Injury, Addiction. The anthology springs from my personal experience with the death of my first wife Lana in 1985. I was a very young widower and the experience re-directed the course of my life. But the call for submissions for this anthology brought so many responses that I knew that the anthology would go far beyond the obvious “poetry of loss.” As the submissions rolled in, they drove the categories of recovery. Though I did solicit a few poems from “name” poets, I also found much wonderful poetry submitted by very good poets who were not well known in the academic world. After Shocks sold very well and continues to reach audiences. Recently, the Kurdish poet and activist Nazand Beghikani asked for 20 copies to distribute at a Paris-based conference on Kurdish Women’s Rights.

In creating this anthology, I unwittingly created a community of 115 poets around the world, many of whom I’m still in touch with, and many of whom now communicate with each other via email, Facebook, etc. So the life of After Shocks continues through them. About a year ago, I started the Poetry of Recovery blog (www.poetryofrecovery.blogspot.com) where I feature an After Shocks poem and an interview with the poet, and I also feature new work or readings by After Shocks poets. I love these poets and their work and want to spread the word about them. In good faith, they submitted their poems to me—an unknown editor at the time—so I hope to extend my gratitude to them forever. I also met Kevin Watson, Press 53’s publisher, through After Shocks, and he and I clicked, and he asked me to start a poetry series of my selections for Press 53.

One After Shocks poet, Satyendra Srivastava, Indian born British poet who’s emeritus faculty at Cambridge, liked one of my poems so much that he translated it to Hindi and placed it in Pravasi Duniya, a daily newspaper in Delhi that features poems. I met Satyendra when I invited him to an After Shocks panel at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. Such a wonderful and brilliant man and great poet. He has invited me to read with him in India. Wow, I’d love to do that someday!

CG: What else do you want to tell me about What Bends Us Blue? Like: where can readers find out more, learn where and when you’re giving readings, and so on.

TL: I’d like you to know that What Bends Us Blue is not only about grief and recovery. It’s about What Comes Next. And it has its fair share of humor and fantasy. Thomas Lux notes, “What Bends Us Blue is part elegy, part praise for the Human and The World, part funny, tough defiance of the inevitable, and ALL memorable.” My publisher says, “What Bends Us Blue mixes wry humor and heartbreaking lyricism, makes beauty from sadness, joy from pain.”

So, buy it at Amazon.com www.tinyurl.com/whatbendsusblue or Barnesandnoble.com. I have copies, too, which I’ll sell at a discount. Send $14 to me at Suite 500, 1401 Peachtree St. N.E., Atlanta, GA 30309. I’ll cover the postage.

I will be posting the details, locations, and times of my reading schedule at the book’s Facebook page www.facebook.com/whatbendsusblue, but note that I’ll be reading this Fall in Atlanta on Sept. 11 and Sept. 12, Charleston, SC, on Oct. 14, Asheville, NC, on Nov. 3, Cary, NC, on Nov. 17, and Nashville, TN, on Nov. 20, 2014. I’ll also be reading at the Press 53 offices at the Community Arts Café in Winston-Salem, NC, as soon as I can arrange that. I also have a radio interview scheduled for Oct. 28, 9 PM Eastern, on RN.FM. You can listen here: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/rnfmradio.

Check the book’s Facebook page for details and times www.facebook.com/whatbendsusblue.

Tom Lombardo is a poet, essayist, and freelance medical writer who lives in Midtown Atlanta. Tom’s poems have appeared in journals in the U.S., the U.K., Canada, and India (translated to Hindi and Mayalayam), including Southern Poetry Review, Ambit, Subtropics, Hampden-Sydney Poetry Review, Aethlon: The Journal of Sports Literature, Atlanta Review, New York Quarterly, Chrysalis Reader, Pravasi Duyina, Thanal Online, Ars Medica, and others. His nonfiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, Best of the Small Press, 2009. He was editor of After Shocks: The Poetry of Recovery for Life Shattering Events, an anthology featuring 152 poems by 115 poets from 15 nations. Tom runs the Poetry of Recovery blog at www.poetryofrecovery.blogspot.com. His criticism has been published in New Letters, North Carolina Literary Review, and South Carolina Review. He earned a B.S. from Carnegie-Mellon University, an M.S. from Ohio University, and an M.F.A. from Queens University of Charlotte. Tom is poetry series editor for Press 53, which is based in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

September 3, 2013

The New Yorker: “The Heron” by Dorthe Nors

September 9, 2013: “The Heron” by Dorthe Nors

September 9, 2013: “The Heron” by Dorthe Nors

I can’t remember another story by a Danish author since I’ve been running this series on The New Yorker’s fiction, so it’s nice to see something new and different. And different it is. Not much of anything happens in the story, which is basically a character study of the narrator, and grumpy elderly man. He sees the ugly side of things, including the herons that inhabit the park he visits. (There’s a great blue heron who sometimes visits the creek that runs through my yard; it’s an amazing looking bird.) To him, the heron looks like death. Also, he has no patience for the young mothers who congregate (“flock”) in the park. And so on. You can a little more sense of what the author is doing in the Q&A with Dorthe Nors.

Otherwise, there’s not much to say. It’s a skilled bit of writing; as “story,” though, it doesn’t do much for me. Still, I’d be interested in reading her collection when it comes out in the U.S. later this year.

September 2, 2013

2013 Reading: Red Moon by Benjamin Percy

Red Moon: A Novel by Benjamin Percy

Red Moon: A Novel by Benjamin Percy

Great cover. But that’s pretty much where my fondness for this book ends. And that’s not really the book’s fault. I generally don’t read science fiction, and I stay away from werewolves and vampires (in fiction and real life). So I probably shouldn’t have even opened this book. But . . . I’ve met the author and I’ve liked his short stories and his previous novel, so I thought I’d give this a try.

As I say, werewolves are not my thing, and this book is so over-the-top with werewolves (“lycans,” technically) that it was a struggle to keep reading. But I did keep reading, and I’m glad I did, because werewolves notwithstanding, there are some important things to learn from this book.

Such as: Be bold. The book doesn’t worry much about realism, or contemporary history, or charges of obvious allegory. All of that is beside the point. We have larger-than-life characters (Chase, the Governor of Oregon, for example, and his sidekick “Buffalo”), we have an Osama bin Laden-like character in “the Master,” the leader of the rebellious lycans, and we have Miriam, a kickass lycan heroine.

Also: Be relentless. While there were a few slow moments, and gore is skippable, for the most part the story grabs you by the throat (with its teeth) and won’t let go. To be sure, it’s so far-fetched that it won’t create nightmares, but it kept me reading if only to find out what would happen to the young protagonists. (I had a pretty good idea, but there were some interesting twists along the way.)

So if werewolves are something you’re interested in, definitely read this book. Otherwise . . . maybe.

September 1, 2013

53-word Story Contest with Prime Number Magazine Returns!

Last year, Prime Number’s publisher, Press 53, ran a fun little weekly contest for very short fictions–53 words, no more, no less (not counting the title). The Press selected a guest judge every week and awarded prizes to the winners. Plus, as editor of Prime Number I picked from among the quarter’s weekly winners and picked a quarterly winner to publish in the magazine.

Last year, Prime Number’s publisher, Press 53, ran a fun little weekly contest for very short fictions–53 words, no more, no less (not counting the title). The Press selected a guest judge every week and awarded prizes to the winners. Plus, as editor of Prime Number I picked from among the quarter’s weekly winners and picked a quarterly winner to publish in the magazine.

The contest took the summer off, but now it’s back, with a few changes. We’ll still have guest judges, but now the contest is monthly. The judge will provide a prompt, which will be posted on the first of the month at the Press 53 blog and on Prime Number’s Facebook Page, and elsewhere. Entries are due by the 15th of the month, and the winner will be announced on the last day of the month. All monthly winners will receive a book from Press 53 as a prize and will also be published in Prime Number (we’ll bundle the 3 winners and put them in our quarterly online issues).

So. It’s the first of the month, and our September judge is Patricia Ann McNair, who wants you to write a story involving a school bus. (It’s that time of year, after all.)

Check out the guidelines here. (You can either email your story to 53wordstory@press53.com, or you can use the nifty app that counts the words for you.)

It’s free to enter, and it’s fun.

August 31, 2013

2013 Reading: What Bends Us Blue by Tom Lombardo

What Bends Us Blue by Tom Lombardo

What Bends Us Blue by Tom Lombardo

This is a lovely collection of poems by a friend of mine. Because it deals with the death of his first wife and meeting his second, the book is both sad and hopeful. His children are present in many of the poems, as well, and that gives the collection a sense of buoyancy; and there’s also a great deal of humor.

The poems, especially in the first two sections, explore “blue” in all its facets–the blues in the music the poet loves. The emotional blues. And the blues in the world around us.

I remember hearing Tom read “How Bill Gates Saved My Marriage” years ago. “My wife doesn’t know it but I track her cycles/on Microsoft Outlook’s calendar function,” it begins. And this isn’t the only bit of humor that you’ll find among the darker work. My favorite poem in the collection, though, is perhaps the darkest and most breathtaking. “When” is an account of getting the call that there’s been an accident. Or maybe my favorite is another horrifying poem, “Split Second to Blink,” which imagines the circumstances of the accident.

It’s a wonderful book and I highly recommend this collection.

August 30, 2013

2013 Reading: The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by Rachel Joyce

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry: A Novel by Rachel Joyce

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry: A Novel by Rachel Joyce

This is a well-crafted book about a quest, and it is filled with charming characters and misfits. In the end, though, I found it overly sentimental and melodramatic. If you like that sort of thing–lots of people do–maybe this is for you.

The story is about Harold Fry, a retiree who learns that an old colleague is dying of cancer. He writes her a letter, but decides that isn’t enough. He’s going to go visit her. On foot. (It’s a trip of about 500 miles, from the southwest of England to the northeast.) It’s the least he can do because of something that happened 20 years earlier. We don’t find out what that something is until the last few pages of the book, however, which contributes to the melodrama and the feeling of manipulation. This and other bits of information are withheld from the reader solely to keep us turning the pages. It’s one thing when the narrative consciousness discovers information along with the reader. It’s another thing, and for me a turn-off, when the information simply isn’t being revealed.

So, be warned. There are things Harold isn’t telling you.

August 29, 2013

Fall For The Book 2013–September 22-27

The first time I appeared at the Fall for the Book Festival at George Mason University, it was a rushed affair for me. I drove up to Fairfax, read on a panel arranged by the Virginia Writers’ Club, and headed home without being able to catch any other readings. Last year, in part because I was also talking to another group in downtown DC, I stayed over at a nearby hotel and was able to take in several other readings, including Wiley Cash and Karen Russell. I’d wished then that I could have done even more because it was a terrific lineup.

The first time I appeared at the Fall for the Book Festival at George Mason University, it was a rushed affair for me. I drove up to Fairfax, read on a panel arranged by the Virginia Writers’ Club, and headed home without being able to catch any other readings. Last year, in part because I was also talking to another group in downtown DC, I stayed over at a nearby hotel and was able to take in several other readings, including Wiley Cash and Karen Russell. I’d wished then that I could have done even more because it was a terrific lineup.

And now the festival is rolling around again (it begins September 22 and runs through September 27) and it looks bigger and better than ever. It remains to be seen how much I will be able to do this year, but I hope I’ll be around for a good bit of it, as many friends will be there.

As it happens, I’ll be participating again myself. A few months ago, I was invited to read at The Writer’s Center in Bethesda and the date we settled on was Sunday, September 22. Coincidentally, that’s the opening day for Fall for the Book, and so, to my delight, my reading (which I’m doing with poet Hailey Leithauser) has been included in the festival schedule.

But take a look at the rest of the schedule, which includes Cheryl Strayed, Dave Barry, Stephen Graham Jones, Ralph Nader, Bob Shacochis, Nathan Leslie, Jen Michalski, Bonnie Jo Campbell, E. Ethelbert Miller, Dean King, Thomas Mallon, Virginia Pye, Ben Percy, Sonia Sanchez, Manil Suri, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Jon Pineda, David Baldacci, and many more. More? How is that possible? I want to see ALL of those great writers, plus the many others I don’t yet know about. It’s an amazing opportunity.

Check out the whole schedule, here: Fall for the Book 2013

Guest Post: Richard Krawiec

Approaching Grace: Accessibility and Reflection in Poetry

Approaching Grace: Accessibility and Reflection in Poetry

Richard Krawiec, author of She Hands Me the Razor

There’s often a disjunct between what a writer believes is their best work, and what an audience thinks. For a poet, the difference can be one of appreciation for craft or subject matter, or connection on an emotional level. When my collection She Hands Me the Razor was published by Press 53, there were certain poems I knew would go over well in a reading. The title poem, with its exploration of the nature of love as revealed in the act of shaving a woman’s leg, I was certain would draw readers in, and it did: “it is always a matter of finding/another’s boundaries/one’s own limits…”

I was less prepared for the opening poem, “Young Love,” to be as well received as it has been. I like the poem, but didn’t consider it one of my most finely crafted. I placed it first because the structure of the book, a novelistic journey through love, loss and redemption, required I open with the “youngest” poem I had, a first chapter of sorts, so I could move forward chronologically. This was the most youthful poem I had on the theme of love, dealing with that experience of early passion when love was believed to be “a run/of rolled 7s/luck we never/thought/would run out.” I was unprepared for how many people connected with that, how accessible audiences would find the poem’s experiences. Accessible, and resonant.

Conversely, I was surprised at how silent the response whenever I read “There Will Always be a Father,” a poem that explored through the life trajectory of a narrator, how the absence of a father can spin a life out of control, can be a kind of execution: “the sharp, shining blade of a guillotine/a baggie full of rainbow pills/empty vodka bottles tipped across countless counters…” Nice rhythm, music, images – and silence.

I was determined to continue reading that poem, which I thought one of the strongest I’d written, until, at A Gathering of Poets, Press 53’s annual day of workshops, Betty Adcock told me afterwards, “That poem was good.”

I also noted she said nothing about the other, more accessible poems. Her praise allowed me to realize not all poems are equally accessible. That doesn’t mean you write down for an audience, although some do. I believe everything you write should be the best you can possibly do with that particular material. But some poems draw readers in by emotionally engaging them. Other poems are more appreciated intellectually, for their craft.

What you hope is to write work that is both accessible and worthy of reflection, as, I believe, I was able to accomplish in the closing poem, “Approaching Grace”: “I approach grace by watching/the feral curl of white froth/rising sun, chanting woman/the red infusion of morning light/on my lover’s already glowing face.”

RICHARD KRAWIEC has published two novels, a collection of stories, four plays, and a chapbook. He has won fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Pennsylvania Arts Council, and the North Carolina Arts Council (twice). His poems and stories appear in Sou’wester, many mountains moving, Shenandoah, Witness, West Branch, North Carolina Literary Review, Florida Review, Cream City Review, and dozens of other magazines. His feature articles have won national and regional awards. He teaches online at UNC Chapel Hill, where he won the 2009 Excellence in Teaching Award. He is the founder of Jacar Press, a Community Active Literary Publisher.

August 28, 2013

The New Yorker: “The Colonel’s Daughter” by Robert Coover

September 2, 2013: “The Colonel’s Daughter” by Robert Coover

September 2, 2013: “The Colonel’s Daughter” by Robert Coover

This story is free for the reading, so have at it. And it’s something of a mystery, as the Q&A with Robert Coover tells us, so a second reading might be in order. Or not.

Unamed country, unspecified time, characters identified by their roles (Colonel, Deputy Minister, etc.) and not their names. The effect is to suggest any country or every country, but also creates the timeless feel of a myth or folktale.

In this case, the Colonel has assembled a group of people in a planned insurrection against the President. But one member of the group is going to betray them, the President suspects. Who is the traitor?

Beyond that mystery, though, there are some wonderful bits of imagery to consider. The Colonel’s daughter is wearing traditional clothing—that somehow comes off and is passed around among the men to be examined. First the apron, then the vest, then the skirt . . . She represents the traditional past, apparently, and these men who are plotting to find a place in the future struggle to understand her. Then, too, there is the doorway. It’s a doorway to history, we’re told, but it’s also the doorway through which the future must pass.

There’s more here, and there is a nice rhetorical flourish at the end. What do you think?