Clifford Garstang's Blog, page 68

November 6, 2013

The New Yorker: “Weight Watchers” by Thomas McGuane

November 4, 2013: “Weight Watchers” by Thomas McGuane

November 4, 2013: “Weight Watchers” by Thomas McGuane

I’m not sure I like this story much, but I really like the narrator. He is an adult in the construction business who recognizes that his parents’ bizarre marriage has made him incapable of attachment—not just commitment. On the other hand, he really likes building houses for other people, perhaps in hopes that someone will be able to build a marriage more enduring than his parents’.

As the story begins, the narrator’s father is arriving because the mother has kicked him out until he gets his weight down. The narrator is able to help with that, but in the meantime they spar. The father seems to get to appreciate his son a little better and maybe the son appreciates his father more, but he’s happy when the desired weight is reached and he can go home.

The ending of the story says it all: “It’s not that there’s anything wrong with my ability to communicate: I have a cell phone, but I only use it to call out.”

Exactly.

November 5, 2013

The New Yorker: “Samsa in Love” by Haruki Murakami

October 28, 2013: “Samsa in Love” by Haruki Murakami

October 28, 2013: “Samsa in Love” by Haruki Murakami

Okay. I guess. Here we have The Metamorphosis turned on its head. Instead of Gregor Samsa waking up to find that he’s turned into a roach, here the roach wakes up to discover that he is a human, someone called Gregor Samsa.

It’s clever. Samsa must get used to walking on 2 legs, wearing clothes, dealing with the hard-on he develops when the locksmith—a woman, the daughter and sister of locksmiths who because of the troubles cannot leave their home.

The story appears to take place during the Prague Spring, when a blooming of free expression and democracy was crushed by the arrival of Soviet tanks. But there’s no turning back, the story seems to be saying. The enslaved must get used to being human, because “the world is waiting for him to learn.”

The story’s a nice allegory that seems clear enough, I think. Just cleverness on the surface, but about much more—just Kafka’s original was about more than the bug.

November 4, 2013

New approach for me: The Three Act Structure

I’m not suggesting that the Three Act Structure is new to story writing–it’s been around a long time. It’s just new that I’m thinking in these terms.

I’m not suggesting that the Three Act Structure is new to story writing–it’s been around a long time. It’s just new that I’m thinking in these terms.

In my teaching and, to a lesser extent, in my own writing, I’ve always referred to “Freitag’s Triangle” map of the story arc, from inciting incident, through rising action, to the climax, followed by the resololution. This diagram has been called a “straight jacket”–fairly so, in my opinion. It’s helpful for beginners, but we have to realize that good fiction can and probably should deviate from this basic structure.

My own process is more free-form, even if I may end up with a structure that looks more or less like this in the end. I have an idea and I let it live on the page as I write, until I come to an end, eventually, and then circle back in revision to clarify the plot, the characters, the themes, etc.

But I am currently teaching a four-week seminar to college seniors and they have to create a story by the end of our month together. So I decided to try a bit more of a traditional approach with them. We began by talking about the three-act structure of a story and looked closely at Flannery O’Conner’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find” with that structure in mind. We identified the turning point (the Act I climax), the story’s climax, and the resolution. The assignment that I then gave them for the first week was to start their own story, through the turning point. Next week we’ll continue to the climax.

Because they were doing this more intentional process for their stories, I decided I would give that a try too. A couple of days ago, I thought of a story, sketched out my three Acts very roughly, and then in an hour this morning I wrote Act I. Seriously? Yeah, seriously. And over the next week I’ll write through to the story’s climax, which I already know. The resolution is still a little fuzzy to me, but I think that will come.

I wonder if this is the start of something new for me . . .

The New Yorker: “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” by Alice Munro

October 21, 2013: “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” by Alice Munro

October 21, 2013: “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” by Alice Munro

Alice Munro, a frequent contributor to The New Yorker, was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature last month. In tribute, presumably, the magazine ran this story, which originally appeared in the magazine’s issue of December 27, 1999.

Like many of Munro’s stories, it has a structure that is slightly off kilter. It begins with a brief section that takes place during the younger days of the two main characters, Grant and Fiona. The first section ends with Fiona proposing marriage to Grant and Grant accepting.

Flash forward about 50 years. Fiona is now 70 and showing signs of dementia. Reluctantly, Grant takes her to a home where she can be cared for. At first he isn’t allowed to visit, and when finally he is he discovers that Fiona has become attached to Aubrey, a gentleman in the home whose condition is the result of a mysterious virus.

We then learn that Grant was a philanderer in his days a university professor. It is perhaps because of some residual guilt he feels over this that he doesn’t seem to mind Fiona’s attachment. When Aubrey leaves the home, causing Fiona to spin into depression, Grant uses his charms to convince Aubrey’s wife to let him bring Aubrey to the home to visit Fiona. The ending of the story is a bit confusing, but it seems to be that Fiona, in a moment of clarity, realizes who he is.

And what’s the point of the story? That true love is what endures? That dalliances only have power over us if we let them? Because Fiona does seem to know that Grant has always been there for her, even when he was sleeping with other women.

Not exactly a feminist message, but maybe it is one about the power love.

A more thorough discussion of this famous story (including an explanation of the title) is available here.

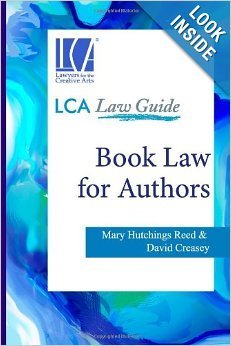

2013 Reading: Book Law for Authors by Mary Hutchings Reed and David Creasey

Book Law for Authors by Mary Hutchings Reed and David Creasey

Book Law for Authors by Mary Hutchings Reed and David Creasey

This is an excellent summary of the basic legal issues facing authors. There are more detailed references available, but this one hits all the right issues. While it is spot-on with regard to the law (I’m also a lawyer, although not a specialist in copyright and publishing), it does make the occasional odd remark about the business, such as: “While writers often submit their stories or poems directly to magazines and journals, book writers almost always need an agent.” That’s true IF you want your book to be published by one of the large trade publishers. There are thousands of smaller presses that accept submissions directly from authors without an agent. In fact, some of the best literary fiction now is coming from smaller presses as the big publishers focus primarily on big commercial books that will make them a lot of money.

Other than that, though, this is a handy guide that I can recommend.

(Note: one of the authors is a former law partner of mine from my days at Sidley Austin)

November 3, 2013

2013 Reading: Out Across the Nowhere by Amy Willoughby-Burle

Out Across the Nowhere by Amy Willoughby-Burle

Out Across the Nowhere by Amy Willoughby-Burle

This is a very short collection of very short stories. The characters are at times rough, but the language is beautiful. I especially liked “Missing Maya,” in which a girl who has a history of disappearing is eventually missed by her friends who then look for her. There’s a bit of sameness to the tone and voice here, so I don’t recommend reading the book in one sitting. Read a story and savor it, then come back later to read the next one.

2013 Reading: Sticklebacks and Snowglobes by B.A. Goodjohn

Sticklebacks and Snow Globes by B.A. Goodjohn

Sticklebacks and Snow Globes by B.A. Goodjohn

One of the things that makes this novel (novel in stories?) unique is its setting—a housing estate in England. Set in the early 70s, we focus on young Tot, a girl in a household on the verge of disintegration who is further challenged by her [mild] epilepsy. Around Tot are the many problems of the lower middleclass in England (and everywhere)—illness, alcoholism, racism, underemployment, teen pregnancy, idleness. Tot herself is an engaging, curious child (a device I’ve used myself, so I like it) and sees things that perhaps adults will not. Surprisingly, not much is made of Tot’s epilepsy, which remains mostly in the background—she has “fits” and she takes medication for them, but other than some teasing by the neighborhood children, the condition has few consequences for her. The stakes for Tot are high, though; her father has dreams of going to New Orleans to make it big in jazz, and Tot makes a deal with God to keep him home.

The chapters read like individual stories, so it’s an easy book to pick up from time to time. An enjoyable read.

October 30, 2013

2013 Reading: The Right-Hand Shore by Christopher Tilghman

The Right-Hand Shore: A Novel by Christopher Tilghman

The Right-Hand Shore: A Novel by Christopher Tilghman

This novel–the first book I’ve read by Tilghman–was one of the three finalists for the Library of Virginia Award for Fiction this year, along with The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers and my own What the Zhang Boys Know. While I know my book is good, I feel even better about winning the Award after reading the other two books.

I’ve written earlier about The Yellow Birds but now I can say that The Right-Hand Shore is also an exceptional book. It’s structure is unique, in my reading experience. It begins in the present time of the narrative (1920s) when a visitor arrives at Mason’s Retreat (a vast estate on the Eastern Shore)–a possible inheritor of the property. He is interviewed by Mary Bayly who is seeking to determine if he is suitable to take the reins of the operation, a farm that has transitioned from tobacco to peaches to dairy. After his meeting with Mary, he meets with Mr. and Mrs. French, the farm manager and his wife who have worked for Mary’s family for decades. The succeeding chapters are the stories they tell about the various players in the family history, until we finally circle back to the present time having learned the secrets of the family and the estate.

It’s a convoluted story, with a lot of characters, but it wrestles with big themes. It’s a terrific historical novel.

October 25, 2013

2013 Reading: Sacred Economics by Charles Eisenstein

Sacred Economics: Money, Gift, and Society in the Age of Transition by Charles Eisenstein

Sacred Economics: Money, Gift, and Society in the Age of Transition by Charles Eisenstein

Judging by comments I’ve heard about this book, the author has something of a cult following among refugees from capitalism–the folks who want to escape from the reality of modern, corporate-controlled, globalized existence.

I want to be sympathetic with these views, but I just can’t. There is too much about the argument offered by this book and others like it that is based on faulty, or at least unsubstantiated, assumptions. Yes, we could be headed for a societal collapse that will fundamentally alter the global economy, but that’s not a foregone conclusion, and Eisenstein seems to treat it as if it is. On page after page, the author makes assertions–statements that he offers as fact and then uses as jumping-off points to reach conclusions that sound reasonable–but offers no evidence.

Furthermore, in order to buy into the argument, one has to reject classical economics, and I’m just not able to do that. The book is interesting, but ultimately unconvincing.

2014 Pushcart Prize Ranking of Literary Magazines

These rankings of literary magazines are based on a simple formula that takes into account all of the Pushcart Prizes won and Special Mentions received over a rolling ten-year period (i.e., 2005-2014 for this year’s list).