Clifford Garstang's Blog, page 56

January 5, 2015

2015 Reading: Creative Nonfiction, Issue 53, Fall 2014

My subscription to Creative Nonfiction is new and this is the first issue I’ve read. I read essays from time to time, of course, but usually not so many all at once. I have to keep reminding myself that they aren’t short stories. Oh, yeah. This is real.

My subscription to Creative Nonfiction is new and this is the first issue I’ve read. I read essays from time to time, of course, but usually not so many all at once. I have to keep reminding myself that they aren’t short stories. Oh, yeah. This is real.

The theme for this issue is Mistakes, which is a great theme. I’ll only mention some of my favorites from the thematic part of the issue. The best, I think, is “Lessons” by Catherine Musemeche, an excerpt from her book. The author is a pediatric surgeon and in this piece she recalls learning from an experienced doctor about being extra careful, and how to deal with mistakes. But she also recalls her own mistake, or what may have been her mistake, one that she managed to catch during surgery before it had catastrophic results. Also interesting was “Still, Standing” (the comma placement being quite deliberate) by Ennis Smith, about the author’s foray into nude modeling during a period of unemployment. And then there’s the horrific piece, “Don’t Scream,” by Bill Pitts, about “extreme forms of protest in a prison work camp.” Yeah, I’d call 36 intentionally broken legs pretty extreme.

But I also enjoyed two pieces outside of the thematic section because they’re by friends of mine (who happen to be fine writers). First is “The Correctors” by Carol Fisher Saller. Carol is a copyeditor, and in this piece she notes wryly that sometimes copyeditors make mistakes, too. So she admonishes readers to be forgiving of the occasional typo in printed work. “A typo is a typo,” she says, “not a sign that the barbarians are at the gate.” (Oh, boy, I’m guilty of loud complaints about typos in books I’ve paid nearly $30 for, but I’ll try to let those go in the future. I’ll try, but I probably won’t succeed.) More importantly, she suggests educating yourself about the current state of things. After all, some of what we learned about punctuation has changed since we were in school (at least when I was in school). Good advice.

The second is something of an experimental piece by Scott Loring Sanders about his father. It’s called “My Father” and every paragraph begins with those two words. The effect is quite moving.

The last piece I’ll mention is “Platforms are Overrated” by Stephanie Bane. Although the author is a newly minted MFA, she has extensive experience with an ad agency and recently has worked in digital media. She says that the conventional wisdom that you have to have a platform is bullshit. (Her term, not mine.) What’s true about her argument is that social media and blogging isn’t as effective a tool to sell books as we’ve been led to believe, or maybe as used to be the case. The Catch 22 is that the publishing industry—agents and editors—hasn’t figured that out yet. So for most of us looking to land a book deal, the platform is still valuable. What happens after the book gets published is another story.

But even then, I’m not sure she’s right. I think of Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Now, by all accounts, that’s a fine and important book. (I confess that I own it but have not yet read it.) But part of what made the book a bestseller is that Skloot prepared the ground for it by building the best platform ever. Here’s a discussion of her experience. The point is that platform building isn’t just about Facebook, Twitter, and a blog post now and then, and I’m not sure Bane gets that. So read this piece, but take it with a grain of salt. We all have to do what we can and what we can afford to get the word out about our work. For some of us, the tools are pretty limited.

January 4, 2015

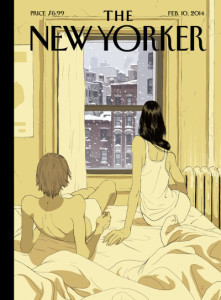

The New Yorker: “Moonlit Landscape with Bridge” by Zadie Smith

February 10, 2014 “Moonlit Landscape with Bridge” by Zadie Smith

February 10, 2014 “Moonlit Landscape with Bridge” by Zadie Smith

I enjoyed this story, and also enjoyed the Q&A with Zadie Smith which sheds interesting light on her process. (I especially like her admission that the title, and its reference to the painting owned by the story’s main character, came late, after The New Yorker rejected her original title.)

In the story, a storm has just devastated an unnamed country. The Minister of the Interior, having already sent his family ahead to Paris, is fleeing with, among other possessions, an expensive painting. The trip to the airport is difficult, and along the way he and his driver encounter an escaped convict (the prison having been destroyed in the storm). Through the mechanism of this convict, known as “The Marlboro Man,” much of the Minister’s past is revealed. This past is familiar to anyone who has observed governments in developing countries. The Minister isn’t completely heartless, but he is corrupt, and he knows he’s leaving his people in the lurch.

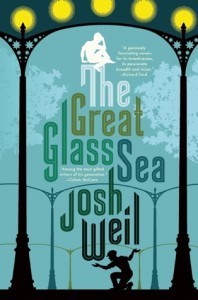

2015 Reading: The Great Glass Sea by Josh Weil

The Great Glass Sea by Josh Weil

The Great Glass Sea by Josh Weil

I consider the author to be a friend. He’s a good guy and, more to the point here, a terrific writer. We did one poorly attended reading together in Charlottesville a few years ago when he published his first book (The New Valley, a collection of novellas) at about the same time my first book, In an Uncharted Country, came out. I heard him read from this new book at the AWP Conference in Seattle in early 2014 and then again at a program at WriterHouse in Charlottesville, where he was also interviewed by a professor of Russian literature. I also did an interview with Josh several years ago in which he mentions that he was at work on this novel. So it’s terrific to see the final product.

The Great Glass Sea is a beautiful book. The language is lyrical, the concept (near future orbiting mirrors create endless daylight for an enormous greenhouse in Russia) is clever, and the parallel story about the relationship of twin brothers is intensely moving. I find that I’m drawn to narratives about sibling conflicts (that’s what I liked most about Elizabeth Strout’s The Burgess Boys), and that’s really at the heart of Josh’s book. So, on all those levels, this is a deeply rewarding read.

It’s not a fast read, however. I confess that it took me a long time to get through the book, which is only 460 pages long—not as massive as some, but longer than most these days. But because the plot, especially in the first half, is not fast-paced, and because the language is dense, it just takes a while to penetrate.

The story is about Dima and Yarik, twins who lost their father and beloved uncle at a young age, back in an idyllic world. Now, though, things have changed. A Russian billionaire has developed the Oranzheria, a massive greenhouse, and has also launched satellite mirrors that reflect light to the greenhouse to extend the growing hours. The project has monumental effects on both the environment and society, one of which is to drive the twins apart. There is already strain between them, though, because Yarik has married and had children, while Dima is left to take care of their ailing mother. While the huge project and the politics surrounding it drive the plot, what appealed to me most is the evolving relationship between Dima and Yarik. Ultimately, that’s the level on which the book satisfies.

Highly recommended.

January 3, 2015

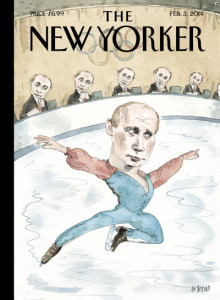

The New Yorker: “The Emerald Light in the Air” by Donald Antrim

February 3, 2014: “The Emerald Light in the Air” by Donald Antrim

February 3, 2014: “The Emerald Light in the Air” by Donald Antrim

Still getting caught up with old stories. I remember hearing about this one last year because it’s set in this area. It’s fun to hear about local places—Charlottesville, Crozet, Afton Mountain.

After a confusing opening, this story, narrated by Billy French, a middle-school art teacher, continues in choppy sentences that seem to reflect suicidal Billy’s need for stability. Driving home in an old Mercedes, anticipating a date, he comes upon a downed tree branch and in trying to get the car past it he gets stuck, and then when he leaves the car it tumbles down the embankment. He’s still grieving for his dead parents and his dead relationship with Julia, the painter he’d lived with, as he deals with this problem, trying to drive the car back to the road. But he gets stuck again and is spotted by a boy who mistakes him for an expected doctor come to help with his sick mother. Billy doesn’t at first reveal the truth, although the boy’s father guesses it. The family is squatting in a shack in the hollow and the mother is dying of cancer. Because of the still-recent loss of his parents, Billy is sympathetic. At first he says he can’t help, but he realizes he has Ativan in his pocket. This he can do.

And of course this way of helping the woman is his redemption. Miraculously, the boy is able to rescue Billy’s car and Billy makes his way home.

I like it. As Antrim says in the Q&A with Donald Antrim, “Billy’s prognosis is good.” And I was pleased to see that the book, of which this is the title story, is already out: The Emerald Light in the Air: Stories

2015 Reading: VQR, Winter 2015

Virginia Quarterly Review, Winter 2015, Vol. 91, No. 1

Virginia Quarterly Review, Winter 2015, Vol. 91, No. 1

I think literary magazines are great, both print and online. My habit, though, is to let the print magazines pile up, unread. For years. I recently had to move all my old copies of journals into boxes to make room on the shelves for all the unread books that had accumulated on the floor. Really. And new magazines arrive weekly, so it’s not as if the boxes solved a problem.

It is imperative, therefore, that I do a better job of reading the magazines and passing them along to other people. No more hoarding for me. There just isn’t room.

I start this initiative with the magazine that arrived most recently, the Winter 2015 issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review. I’ve long admired this journal, and because it is based in Charlottesville, not far from where I live, I’ve had some interaction with its staff over the years. It’s a beautifully produced book, and everyone should subscribe, or at least find a copy and read.

Having said that, I have mixed views on this new issue, which I guess is okay. There’s something in it for everyone. I actually liked the nonfiction more than the fiction. Let’s break it down.

There’s an interview called “Going Rogue” with some rogue taxidermists—people who stuff animals unconventionally. Never heard of such a thing, but it sounds pretty interesting, and the photographs are fascinating. There’s also an interview with Derek Walcott which is interesting. His answers are terse (although that might be in the editing) but the discussion ranges from Pasternak to Wordsworth to Seamus Heaney.

A section called “Talisman” is an essay by Andre Dubus III called “Beneath,” which is about the evolution of his workspace. I enjoy reading about writers’ desks and studies, so this was great. As it happens, I recently read his memoir, Townie, and am currently listening to the audiobook version of The House of Sand and Fog, which I’m enjoying.

“Snowfall Blues” is an essay by Alison Stine about Jackson C. Frank, a musician I’ve never heard of. The writer seems at a great distance from her subject, but the piece is clear and well written and informative.

And speaking of informative, “Art and Politics in Occupied Crimea,” by Dimiter Kenarov with photographs by Boryana Katsarova is fascinating, and covers exactly what you might expect from the title. Curiously, we also get an essay about Russian immigrants in the US in Liesl Schillinger’s “My Midwestern Soviet Childhood.”

Given recent racial tensions in this country, I was really drawn into Thomas Chatterton Williams’s piece, “Black and Blue and Blond.” Of mixed race, but identifying as Black, he married a French woman with whom he has a blond child. Needless to say, there are issues. There’s a long essay about health care for undocumented immigrants in Houston that I confess I only skimmed, and another piece, by Kwame Dawes, “The Guardy and the Shame,” about homophobia and AIDS in Jamaica.

Which brings me to the fiction, usually the section of a journal I focus on.

The first story, “The Fathoms,” by Amanda Korman was enjoyable if only that it deals freshly with a familiar issue. What’s familiar is whether a young couple should have a child. The wife is working, the husband is in school (perpetually, it seems). What’s fresh is that this is a Jewish couple in Washington DC (he is, apparently, more observant than she), and she’s going regularly to a mikvah, which (and this was what was new to me) is a ritual immersion bath for purification. She wouldn’t be going to the mikvah if she were pregnant, however, which everyone assumes is her goal. Except she’s on the pill, which she hides from the woman who runs the mikvah.

I didn’t care for “Dead Right There” by Aaron Gwyn. All the stories about the war in Iraq seem the same to me, and there have been a lot of them lately.

“Soucouyant,” by Tiffany Briere, is probably my favorite of the four stories in this issue. It deals with a family of immigrants from Guyana, including a daughter, Suku, who is a post-doc at Yale working on genetic analysis of aggression in mice (or something like that). She gets a call from home and learns that her father, Sherlock, will be having both legs amputated due to diabetes. She goes home, even though she’s estranged from her father and sister, and isn’t sure what she’s going to do. I don’t think she’s surprised by the ethical dilemma her father presents her with though, and the story leaves us hanging. Loved the ending.

Of the four stories in this issue, the only one by an author I’m familiar with is “Avarice” by Charles Baxter. I like Baxter’s work and studied with him at Bread Loaf years ago, but I can’t say I loved this story. Told from the point of view of a religious woman recently diagnosed with breast cancer (which she assumes is fatal, apparently), the voice seems forced. In the first person, she talks about her life, her husband’s death (hit by a drunk driver), and interacts with her former daughter-in-law who now lives with her (as does her son and his current wife, along with the son’s two children, one with each wife).

I’ve gone on about this issue much longer than I intended, but VQR is always packed.

January 2, 2015

2015 Reading: Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

Gulliver’s travels by Jonathan Swift

Gulliver’s travels by Jonathan Swift

The edition shown is a beautiful book with illustrations, historical notes, and a few critical essays. I picked it up at the local used bookstore not too long ago, and I’m happy to keep it in my library. But the edition I actually read was the Norton Critical Edition Revised, which I’ve had for probably 40 years. It’s binding is crumbling, there are numerous underlinings–both from this reading and past–and the book’s days are numbered.

Probably it has been a long time since you read Gulliver’s Travels, too. I read and taught “A Modest Proposal” by Swift in composition courses, but I’ve been wanting to refresh my recollection of Gulliver’s voyages for some time. Odd as it may sound, the book is relevant to the novel I’m working on now, so my reading was research.

It’s good to dip into classics now and then. Keeps us writers honest.

2015 Reading: “Gulliver’s Travels” by Jonathan Swift

Gulliver’s travels by Jonathan Swift

Gulliver’s travels by Jonathan Swift

The edition shown is a beautiful book with illustrations, historical notes, and a few critical essays. I picked it up at the local used bookstore not too long ago, and I’m happy to keep it in my library. But the edition I actually read was the Norton Critical Edition Revised, which I’ve had for probably 40 years. It’s binding is crumbling, there are numerous underlinings–both from this reading and past–and the book’s days are numbered.

Probably it has been a long time since you read Gulliver’s Travels, too. I read and taught “A Modest Proposal” by Swift in composition courses, but I’ve been wanting to refresh my recollection of Gulliver’s voyages for some time. Odd as it may sound, the book is relevant to the novel I’m working on now, so my reading was research.

It’s good to dip into classics now and then. Keeps us writers honest.

January 1, 2015

The New Yorker: “Under the Sign of the Moon” by Tessa Hadley

March 24, 2014: “Under the Sign of the Moon” by Tessa Hadley

March 24, 2014: “Under the Sign of the Moon” by Tessa Hadley

Greta, in her 60s, is traveling by train from London to Liverpool to visit her daughter Kate. She is sitting across from a young man, who seems a bit odd and lonely. He’s on his way to visit relatives, and he obviously wants to talk, although Greta wants to be left alone. She’s dealing with her health—illness that she’s not completely recovered from has led to a hysterectomy—and also with her past, because Liverpool is where she lived with Ian, who was not exactly her husband but was Kate’s father.

The young man, whose name she later learns is Mitchell, has recently lost his mother. Greta feels a bit sorry for him, and when he mentions the possibility of meeting up for coffee one day in Liverpool, she gives that some thought. She enjoys her time with Kate and her husband Boyd, but there is some distance there, which Greta seems to regret. So when the time comes, she does go to see Mitchell. She’s at the same time thinking a good deal about Ian, and to a lesser extent about Graham, her current husband.

She does meet Mitchell, more or less by accident, and he is disturbing; she is now repulsed by him.

Although this is part of the point, the story dwells too much in the past, for me. (In the Q&A with Tessa Hadley, the author says that the character’s observation of the carved train tunnel is meant to draw her into the past, and indeed that’s a major part of what the story is doing.) I do like Hadley’s work, though, and she frequently has these odd encounters as we see here between Greta and Mitchell. He’s creepy and she’s melancholy, and the combination is compelling.

The New Yorker: “The Ways” by Colin Barrett

January 5, 2015: “The Ways” by Colin Barrett

January 5, 2015: “The Ways” by Colin Barrett

Here’s what I didn’t like about this story: (1) Little sense of place. Because Pell has to take a bus the 7 miles to Gerry’s school, we understand it must be somewhat rural, but we get no sense of the actual house the family lives in and it took me awhile to guess that the story is set in Ireland. (2) Head hopping. The story begins in Pell’s point of view. She’s the 16-year-old girl in the family and she answers the phone when the call comes that Gerry’s been in a fight at school and someone needs to come get him. Later we’re in older brother Nick’s head when Pell and Gerry show up at his work. Then we shift to Gerry’s head at the end of the day. Normally, in a short story, that would be too many points of view. I understand that this is the point, in this story, that we are mean to experience “the ways” in which these three are coping with the deaths of their parents. Still, I wonder if this was the right choice. (3) Has the passive voice come back into style? If this story were submitted in workshop, I’d say there were too many instances of the verb “to be,” and that this signaled too much telling and not enough showing.

Having said that, I did feel engaged by the story, because the ways in which these kids are coping are compelling and different, revealing very different personalities. Still, we don’t get to stay with any one of them long enough. The story, apparently, is part of a collection that will be published in the US this year, but I wondered if it might not be part of a novel. The stories of these three survivors would definitely pull me into a longer work.

The New Yorker: “The Relive Box” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

March 17, 2014: “The Relive Box” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

March 17, 2014: “The Relive Box” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

I’ve never been much of a T.C. Boyle fan, as readers of my New Yorker commentaries may remember. I have to say, though, that this story grabbed me for both its voice and its inventiveness. Normally, flashbacks can ruin a short story, but here, because of the Relive Box, the flashbacks are the whole point. And I wonder if, on some level, that’s what Boyle is saying.

In any case, Wes is the father of Katie, a young teen. Both of them are wallowing in a happier time when Christine, Wes’s ex-wife and Katie’s mother, still lived with them. And “wallow” is the right word, because both seem to be addicted to the Relive Box, a futuristic device that replays a person’s past based in a retinal scan. In Wes’s case, at least, the past is relived over and over again, not only his past with Christine, but also his relationships before Christine, and even back to traumatic childhood events. And he’s truly addicted, to the point that he’s in danger of being fired (although he suspects that his boss and co-workers have similar problems). When Katie goes away for a ski weekend with a friend’s family, Wes dives into his past so deep that he might never come out.

What’s Boyle saying here? We are a product of our pasts—the day we learn that our dog died, the day we break up with the girl we’re in love with, etc. But he also seems to be saying that living in the past is a kind of death, or at least paralysis. Get rid of that Relive Box. Live in the present.