Clifford Garstang's Blog, page 52

February 16, 2015

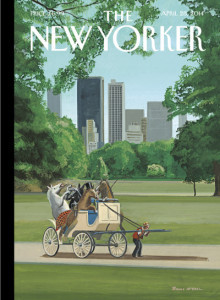

The New Yorker: “The Waitress” by Robert Coover

May 19, 2014: “The Waitress” by Robert Coover

May 19, 2014: “The Waitress” by Robert Coover

The Q&A with Robert Coover doesn’t help.

I’m just not a fan of these reimagined fairy tales of Coover’s. I find them lacking in significance, to put it mildly. I’m sorry if that offends you Coover fans out there.

This one involves a waitress who serves some soup to a bag lady. When she wishes out loud that she like for people to stop looking at her—another customer has ogled her behind—suddenly her wish is granted. Everyone’s head snaps away from her and no one can look at her. The waitress suspects the bag lady, who has disappeared.

The waitress knows not to squander her wishes, so her last wish is for wealth, which arrives in the form of the abandoned loot from a bank robbery. She’s afraid taking the cash will result in more problems for her, but the security cameras can’t look at her (thanks to the first wish), so she grabs the bags of money and jumps into a cab.

The end, more or less.

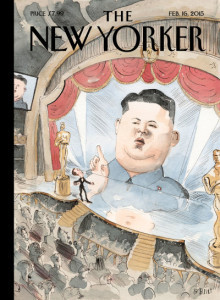

February 15, 2015

The New Yorker: “Labyrinth” by Amelia Gray

February 16, 2015: “Labyrinth” by Amelia Gray

February 16, 2015: “Labyrinth” by Amelia Gray

In the Q&A with Amelia Gray we learn that the story is a retelling of the Theseus myth.

The story begins realistically. The townspeople turn out in force for a carnival, especially the corn maze that Dale puts on every year to benefit the local fire department. Dale (Daedalus?) is doing things a little differently this year, though, and has created a labyrinth instead of a maze (unicursal instead of multicursal). He also explains that this labyrinth has magical properties in that in the center you discover the one thing you desire most in the world. Most people turn away from the labyrinth at this point, but Jim, the main character, pays his money and agrees to enter. Inside, he can hear the voices of the other people and he realizes that they all consider him a coward because of something he’d done previously. He moves deeper into the labyrinth, though, and still hears the voices—except now they’re speaking of him with admiration for his courage.

Jim, apparently, wants to be admired by the townspeople. At the end, he is drawn to what is almost like a shallow grave and wonders if he might see the Minotaur (the beast slain by Theseus). Is that because Jim thinks killing the beast would further cement the new opinion the people have of him? Perhaps, but it isn’t clear that he’ll ever be able to emerge from the labyrinth now, so their opinion won’t do him much good. And maybe THAT’s the point.

February 14, 2015

The New Yorker: “The Fugitive” by Lyudmila Ulitskaya

May 12, 2014: “The Fugitive” by Lyudmila Ulitskaya

May 12, 2014: “The Fugitive” by Lyudmila Ulitskaya

It’s unfair, I suppose, to apply American standards of story-telling to a piece of Russian fiction, but I didn’t care for this at all. The story being told is fine; it’s the method, which is mostly telling and very little showing, that bothers me.

Boris is a dissident artist and his anti-government cartoons have become well known. As a result, the KGB comes to arrest him, but he is able to slip away and escape to the countryside, where he takes refuge in a friend’s dacha. He’s bored and begins to draw pictures, including those of the local women who help him. He continues to avoid arrest for several years, but he becomes reckless and is eventually caught. Instead of being charged with sedition, though, he is jailed for pornography. He’s out in two years, emigrates, and remarries.

I suppose the story is a commentary on Soviet absurdities and the deprivations of the Russian people during the Soviet era. Unfortunately, the way it’s written makes it difficult to enjoy whatever the message might be.

February 11, 2015

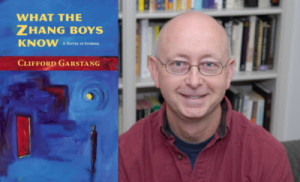

WHAT THE ZHANG BOYS KNOW reviewed at Late Last Night Books

You go months or years without a review and then two are published in the same week. Go figure.

You go months or years without a review and then two are published in the same week. Go figure.

Please check out this review of What the Zhang Boys Know at Late Last Night Books. Reviewer Sally Whitney, writing about the diverse characters in the novel in stories, says:

“Each of these people is worthy of attention. One of Garstang’s strengths as a writer is his ability to make each character distinctive, totally distinguishable from other characters in action, thought, and language . . . And yet, as memorable as each character is, the soul of the novel is the way their interactions with each other exacerbate or resolve their problems.”

I’m gratified by this reviewer’s reaction to the book.

February 10, 2015

2015 Reading: Unpacking the Boxes by Donald Hall

Unpacking the Boxes: A Memoir of a Life in Poetry by Donald Hall

Unpacking the Boxes: A Memoir of a Life in Poetry by Donald Hall

Over the years I have read an occasional Donald Hall poem, but I can’t say I’m familiar with his work. But he appeared on a recent cover of Poets & Writers, so I thought it was time I corrected that. While looking for his work in the poetry section of a used bookstore, I came across this book, one of his memoirs. That seemed like a good place to start, so I bought it.

The book is fascinating. It has a dual beginning—Hall’s early interest in poetry as a boy and then the triggering of his memories as an older man returning to New Hampshire, unpacking the boxes.

After a couple of years in a public high school, he moves on to Phillips Exeter Academy and then Harvard and then Oxford, mingling with some of the 20th Century’s most important poets. He drops their names, but it doesn’t feel like name dropping because he is increasingly becoming one of them. He goes into some depth about his stays at Harvard and Oxford, presumably because these were so important to his development, but he breezes over his first marriage—too painful?—and his second, to Jane Kenyon, which he has written about elsewhere. (Interesting: the book he has written about their marriage was originally the middle section of what became this book, but it was extracted and expanded.)

The chapter I found most interesting, though, has least to do with poetry. The last chapter, “The Planet of Antiquity,” deals with what it is like for him to be getting old. And the book was published seven years ago, so he’s only that much older now.

Having come to know him a little through this book, I look forward to reading his poetry.

February 9, 2015

WHAT THE ZHANG BOYS KNOW reviewed at Peace Corps Writers

Despite the best efforts of my publisher, Press 53, and my own due diligence, my book WHAT THE ZHANG BOYS KNOW received few serious reviews when it came out in 2012. It was mentioned on quite a few blogs (as part of a “book blog tour” I arranged), but for the most part these commentaries did not really include reviews. Even after the book won the Library of Virginia Award for Fiction in 2013, it garnered little attention.

Despite the best efforts of my publisher, Press 53, and my own due diligence, my book WHAT THE ZHANG BOYS KNOW received few serious reviews when it came out in 2012. It was mentioned on quite a few blogs (as part of a “book blog tour” I arranged), but for the most part these commentaries did not really include reviews. Even after the book won the Library of Virginia Award for Fiction in 2013, it garnered little attention.

It is a pleasant surprise, then, when more than two years after publication a review does appear. This one is at “Peace Corps Writers,” a component of a website called “Peace Corps Worldwide.” The review, by Jan Worth-Nelson, is here.

Peace Corps Writers, which began as a print publication, has done a wonderful job of highlighting the work of the very many Returned Peace Corps Volunteers who have become writers. Among other things, it sponsors the Maria Thomas Fiction Award, which my first book, IN AN UNCHARTED COUNTRY, won in 2010.

February 8, 2015

New Magazine: Sixpenny

Just heard about Sixpenny, a new magazine of six-minute illustrated fictions. Set to launch next week.

Just heard about Sixpenny, a new magazine of six-minute illustrated fictions. Set to launch next week.

Check it out!

February 7, 2015

The New Yorker: “The Naturals” by Sam Lipsyte

May 5, 2014: “The Naturals” by Sam Lipsyte

May 5, 2014: “The Naturals” by Sam Lipsyte

Caperton is a consultant (in what area isn’t exactly clear—landscaping?) but is on his way from his home in Chicago to Newark because his father is dying. He is seated on the flight next to a professional wrestler who says that his sport is all about storytelling, which is similar to something another consultant had said to him in a recent meeting, and Caperton finds this odd. Caperton’s father has claimed to be on his death bed before, but it seems to be true this time, according to Stell, the father’s current wife. Caperton meets his stepmother at the door when he arrives. They have a good relationship—his own mother is dead—but she has a problem with his rooting in the refrigerator, so of course he likes to do that just to get to her. The fact that the father really is dying, now seems to affect Caperton, and everything is about storytelling, which seems to be the point of the story. He tries to contact his ex to talk to her after the father does in fact die, but her current lover protects her from him. On the return flight, he is comforted by the pro wrestler.

Huh? There are some funny lines in the story, although I’m not sure the theme of “storytelling” really comes through for me.

The Q&A with Sam Lipsyte doesn’t shed much light on it, but there are some interesting comments.

February 4, 2015

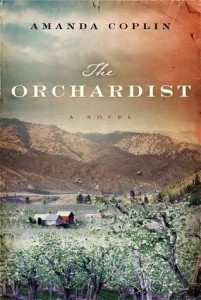

2015 Reading: The Orchardist by Amanda Coplin

The Orchardist: A Novel by Amanda Coplin

The Orchardist: A Novel by Amanda Coplin

I first became aware of this novel when we ran an interview with the author in Prime Number Magazine, which you can read here: Interview with Amanda Coplin. It sounded like something I might be interested in, so when I saw it listed among available titles for audio books in my Audible.com account, I got it.

The novel is the story of William Talmadge who arrives in Western Washington with his mother and sister following the death of his father, a miner. The family settles on a homestead and begins to develop an orchard, and when the mother dies the brother and sister continue to run it on their own. The mysterious disappearance of the sister one day shapes who Talmadge becomes as a man. Two girls arrive, pregnant runaways, and Talmadge is inclined to help them even when they steal from him, rather than alert the sheriff. The rest of the book reveals his relationship with those girls and the daughter of one of them.

These are great characters: Talmadge himself, the runaways and the daughter, and the older woman in town, Caroline Middy. They’re wonderfully imagined and drawn, and even when they’re making mistakes, the reader is deeply sympathetic. There’s a bad guy in the story, too, of course, and he’s pretty bad, but he’s not so evil as to be unbelievable. The tale progresses in more or less linear fashion, told in alternating points of view–Talmadge, Caroline Middy, the runaways, the girl.

Apart from the terrific characters, the great detail of the time and place stand out here. The work of running the orchard, of selling in the local market, of traveling in the region by wagon, mule, or train–all of this is wonderfully convincing. Coplin has done an outstanding job of creating the environment for this story, which is set at the end of the 19th Century and early 20th. For this, I’m full of praise.

On the other hand, I am less thrilled with the inner lives of these characters. They are constantly debating with themselves–should I do this, or that, should I reveal this, or not that, what should I do? With the exception of Caroline Middy, they all seem too afraid to speak their minds, and as a result the story drags somewhat. But perhaps my frustration with these internal struggles is a function of having listened to the audio version of the book. Skipping ahead, which I might have done if I’d been reading, wasn’t an option!

Still, my overall impression of the book is very favorable, and I’m glad to have experienced it.

February 3, 2015

The New Yorker: “The Man in the Woods” by Shirley Jackson

April 28, 2014: “The Man in the Woods” by Shirley Jackson

April 28, 2014: “The Man in the Woods” by Shirley Jackson

It’s a pleasure to read a previously unknown Shirley Jackson story. Here, a young man, Christopher, is leaving his previous life and takes the road through the forest, accompanied by a cat. But the road ends at a great stone house in the middle of the forest. The residents of the house welcome Christopher and the cat and he dines with Phyllis, Aunt Cissy (Circe), and Mr. Oakes. The house cat, Grimalkin, is defeated in a brief skirmish with Christopher’s unnamed cat, who then inherits both the name and place as house cat. The next day, Oakes shows Christopher the house’s vast records and the roses he has planted. Then, as the evening meal is prepared, Oakes sharpens his knife and goes outside. The women send Christopher after him with instructions.

The Q&A with Shirley Jackson’s son, Laurence Jackson Hyman is quite interesting because it talks more generally about Jackson’s work and also the cache of unpublished and uncollected stories Jackson’s family discovered after her death. As for this story, the interpretation is relatively straightforward when one realizes its mythic and fairy tale origins.