Jake Adelstein's Blog, page 3

October 27, 2024

Corruption, Cults, and Collapse: Why Voters Rejected Japan’s Ruling Party in Major Election Blow

The sins of deceased ex-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe: the slush fund, the failed economic policies, and the ties to the unification church came back to haunt his party.

The sins of deceased ex-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe: the slush fund, the failed economic policies, and the ties to the unification church came back to haunt his party. In a not-so-surprising twist that has Japan’s ruling party licking its wounds, the 2024 lower house election results show the ruling coalition crumbling to pieces. After decades of near-uninterrupted dominance since 1955, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)–which is neither liberal nor democratic–couldn’t escape the weight of its own corruption scandals, failed economic policies, and, perhaps most damningly, its ties to the Unification Church, a group detested by the Japanese public. You won’t hear the Japanese press write much about that aspect of their losses, because the church has begun suing newspapers and media critical of their activities.

For everything you need to know about the Liberal Democratic Party, go to the end of the article!

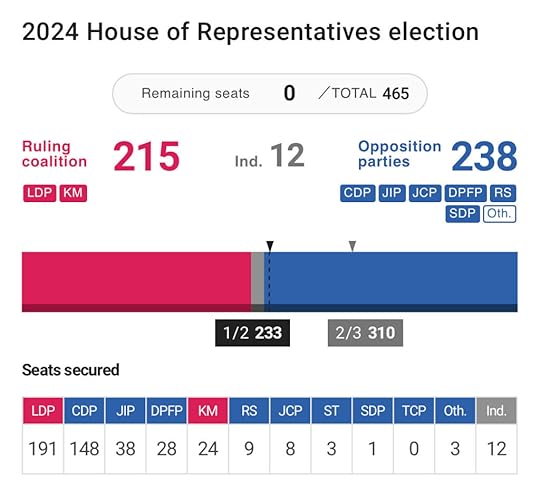

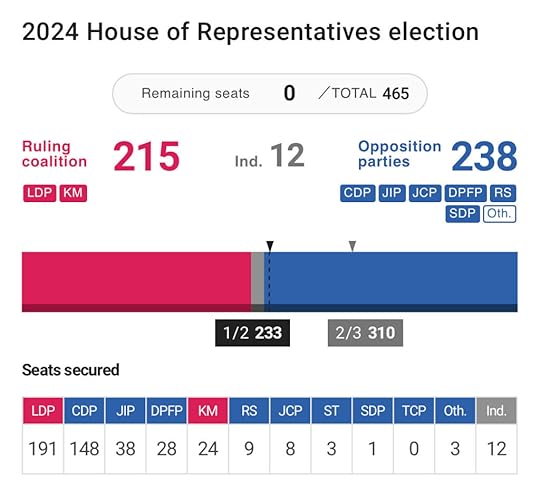

The LDP and their coalition partner Komeito needed 233 seats to hold onto power–they ended up with 214. The LDP itself shrank to 191 seats and their staunchly liberal opposition, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan scored 148, making them the largest opposition party in the lower house of Japan’s Parliament.

The Liberal Democratic Party is composed of many different factions, much like the Yamaguchi-gumi, Japan’s largest yakuza group (founded in 1915) also has various factions vying for power.

The de facto Abe faction, once the shining star of the party, has been irreparably tainted–and were the biggest losers. Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s assassination in 2022 was a political earthquake, but the revelations that followed shook the LDP to its core. Turns out, the beloved leader wasn’t just working on behalf of the people; he and his inner circle were knee-deep in shady dealings with the notorious Unification Church, a group reportedly known for exploiting its members and funneling cash into political coffers.

Economically, the so-called success of Abenomics, which was supposed to lift Japan from its decades-long stagnation, has been revealed to be largely smoke and mirrors—based on falsified data. What it left behind was a gaping wealth gap, inflation that made daily life increasingly difficult, and wages that hadn’t budged in years. Former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida promised to change gears but kept the same failed policies in place. The people of Japan had simply had enough.

This election isn’t just a loss for the LDP; it’s a referendum on a political system that’s been slowly eroding. The rise of the opposition, led by the CDP with 148 seats, signals a shift in public sentiment. Parties like the Japan Innovation Party (JIP) and the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) are now positioned to play larger roles in shaping Japan’s future.

The LDP’s downfall can be seen as a microcosm of the failures plaguing long-standing political regimes worldwide: arrogance, corruption, and an inability to adapt to the needs of a changing society. When power is too concentrated for too long, it begins to rot from the inside out.

The unholy alliance between the LDP and the Unification Church was just the tipping point. This election marks a dramatic turn in Japanese politics, one that may finally bring the long-simmering dissatisfaction with the ruling party to a boil.

The Fall of Hakubun Shimomura Is A Microcosm Of The Greater Problem

In what can only be described as a fall from grace too ironic to script, Hakubun Shimomura, a former education minister, has found himself on the wrong side of a ballot box. After nine consecutive terms in the Tokyo 11th district, Shimomura lost his seat to Yukihiko Akutsu of the Constitutional Democratic Party, and if you’re inclined to celebrate underdog victories, hold your applause—there’s more than just a campaign gaffe or two at play here.

The 70-year-old Shimomura, once a darling of the political elite, couldn’t withstand the mounting scandals that had come to define his career like the pins in a voodoo doll. His name is inextricably linked to an “envelopes-under-the-table” type of affair—let’s call it the “Secret Cash Scandal” (see below). And when you’ve got a moniker like that hanging over you, even the most forgiving electorate starts to ask uncomfortable questions. He had been banned from running on the LDP’s proportional representation list, the political equivalent of being put in the corner with a dunce cap.

There’s something so textbook about his fall, a perfect encapsulation of what happens when the political machine that got you to the top starts churning in reverse. Shimomura is not the only LDP politician whose career has been sabotaged by scandals like these, but his trajectory feels almost like a satire of itself. The former Minister of Education, was once linked to a yakuza associate—who specialized in running school-girl themed sex-shops. He promised to investigate the links between the vice-chairman of Japan’s Olympic Committee and the Yamaguchi-gumi (yakuza group) and then buried the investigation.

He’s the guy who survived nearly three decades of political intrigue, only to be unseated in the twilight of his career by a candidate who spent the better part of two years languishing in relative obscurity. The only thing missing from the narrative is a Greek chorus chanting, “We told you so!”

To add to the irony, Shimomura had been one of the key figures connected to the controversy surrounding the Unification Church, the religious organization formerly known as the Moonies. If you recall, it was his office that oversaw the approval of the group’s name change back in 2015. At the time, it probably seemed like a small procedural matter, but in hindsight, it was the kind of thing that sticks to your political record like gum on a shoe. The ties to the Unification Church not only haunted his campaign but turned the public perception of him into that of a shady backroom dealer—a villain too out of touch to be reformed.

Throughout the campaign, Shimomura made quite the spectacle of apologizing, visiting over 8,000 homes in what one could call his “sincerity tour.” Picture him with his head bowed, muttering apologies like a fallen samurai seeking redemption. It’s a dramatic image, but it wasn’t enough. Shimomura was seen as the embodiment of the LDP’s worst habits—backroom deals, cozying up to questionable organizations, and a blatant disregard for transparency, all of which have soured the electorate’s taste for the party.

These types of scandals are not isolated incidents but rather emblematic of a larger systemic rot within the political hierarchy. Shimomura’s fall is just one more example of the self-inflicted wounds the LDP has suffered, and it raises the question of whether these political titans ever learn. It’s not the scandals themselves that take politicians down, but rather the perception of arrogance and invincibility that seems to precede their downfall.

If we zoom out, Shimomura’s defeat isn’t just about one man’s loss. It’s a microcosm of the deeper issues the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (and frankly, many parties around the world) face in trying to retain the public’s trust while navigating their own internal chaos. The public may forgive a mistake or two, but when the perception of corruption becomes the rule rather than the exception, well, voters decide it’s time for a change.

Their coalition partner, Komeito, didn’t fare well either. Komeito is the political arm of the buddhist organization Soka Gakkai which some have called a cult. It was revealed this year that their spiritual leader, Ikeda Daisaku–who had not been seen in public for over a decade–was actually dead. When he really died, no one knows. Ikeda vanished from public view around the time former Yamaguchi-gumi yakuza boss, Tadamasa Goto, published his biography Habakaringara. In that book, he bragged that he had been doing the dirty work for Soka Gakkai and Ikeda for decades.

The Curse of Shinzo Abe

To truly understand the political implosion of Hirofumi Shimomura and his comrades in this election, you have to consider the broader context of the collapse of the Abe faction and the wreckage left in its wake. For nearly a decade, Shinzo Abe and his loyalists operated with the confidence of autocrats, not just running Japan, but crushing dissent, controlling narratives, and scandalizing the political system like it was part of the job description. Abe himself, until his shocking assassination, wielded immense power behind the scenes, often suppressing freedom of the press and/or corrupting top dogs in the media by wining and dining them. But what finally broke through that iron grip was a revelation so insidious that even Japan’s famously forgiving electorate had had enough.

After Abe’s assassination, the floodgates opened, and it became clear that the prime minister—along with many high-ranking members of the LDP—had been intimately connected with the Unification Church. Yes, that Unification Church, the religious group (or, as most people in Japan prefer to call it, a cult) that has been despised for decades. The fact that Abe and his cronies were not just affiliated with the group but in bed with them on a scale that made voters’ skin crawl sent shockwaves through the nation. It wasn’t just bad optics—it was the epitome of the kind of shady backroom deals that defined the Abe era.

If you’re a student of history, you know that the Liberal Democratic Party was founded with yakuza money by war-time profiteer, Kodama Yoshio and war-criminal Nobosuke Kishi, Abe’s grandfather. From bad seeds, bad things grow. . What should be pointed out is that Abe’s folly wasn’t just a case of a politician playing footsie with an unsavory organization—it was emblematic of the entire Abe faction’s disdain for transparency and democracy. He also cuddled up to sexist right-wing cult, Nippon Kaigi, which opposes many policies that the majority of the Japanese public supports. , But it was the Unification Church link that really damaged his legacy. In fact, his assassin targeted Abe precisely to bring those ties to light. By the time Kishida decided to give Abe a lavish state funeral, 80% of the public opposed the waste of money.

With the public now acutely aware of just how deeply the LDP had been corrupted by its dealings with the Unification Church, the house of cards began to collapse.

As Shimomura learned the hard way, you can only apologize for so long before voters stop listening. His relentless campaign of mea culpas—visiting 8,000 homes to personally apologize—seems quaint when stacked up against the larger issues haunting the LDP. People weren’t just angry at him; they were angry at the system that allowed someone like him to stay in power for nearly three decades.

Abe’s so-called economic success—Abenomics—was supposed to be his legacy. But in reality, it was a carefully crafted mirage built on falsified data from the government. The very foundation of Japan’s economic recovery during his tenure was shaky at best, propped up by manipulation and spin. Wages stagnated, inflation soared, and the gap between rich and poor grew ever wider. Those at the top saw the benefits, while millions were left in a limbo of rising costs and shrinking opportunities. And as Shimomura’s loss shows, voters have reached their breaking point.

This election has been a reckoning not just for Shimomura, but for anyone associated with the Abe faction. Across the board, candidates tied to Abe have fared poorly. His assassination may have removed the man, but the shadow of his scandals, his connections to the Unification Church, and his autocratic tendencies lingers, leaving the LDP scrambling to find a new identity amid the debris.

Shimomura’s downfall is symbolic of what happens when a party—and a political faction—becomes too comfortable in its own corruption. The people of Japan, facing rising inflation, stagnant wages, and an ever-widening wealth gap, have had enough. The LDP has been in power for so long that it forgot it was supposed to serve the public, not control it. And now, as the Abe era truly comes to a close, Shimomura and other Abe cronies are left standing on the street, microphones in hand, wondering where it all went wrong.

Anpanman isn’t stupid: Ishiba’s Power-Play

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has a strange following among Japanese women who think he’s cute, like a mascot. He does resemble Anpan-man, the pastry hero beloved by children. But he’s not a child. At the heart of the LDP’s electoral implosion was a bold move by the current Prime Minister and former defense minister, whose power-play may have gone unnoticed by many. Ishiba, perhaps sensing that the political tides were turning, refused to grant party backing to LDP candidates who had been caught red-handed in the political funds scandal. More notably, he barred these scandal-tainted figures from being listed on the proportional representation roster*, the lifeboat that could have saved many from their inevitable loss in single-seat elections. Without this safety net, politicians like Hirofumi Shimomura found themselves stranded. Ishiba’s arch-enemy, uber-right winger, Shinto fanatic and pit-bull with lipstick, Ms. Takaichi saw her power base erode. Of the 41 LDP candidates Takaichi endorsed in the general election, 31 lost their races. Her political allies in the Diet have been purged by the public.

Ishiba’s strategy was clear: cut the party’s losses and purge the taint of corruption, even if it meant temporarily weakening the LDP’s grip on power. It was a calculated gamble, one that not only distanced the party from its most scandal-ridden figures but also conveniently eliminated many of his own political rivals within the LDP. The result? A weakened party, stripped of its old guard, and left to face an emboldened opposition. In the short term, this maneuver accelerated the LDP’s downfall and handed a decisive victory to the opposition. Whether this will be remembered as a tactical masterstroke that ultimately saved the party, or the final nail in the coffin of the Abe-era LDP, remains to be seen.

The Liberal Democratic Party: who are they?

Imagine Japan as a stage and the LDP as the lead actor, playing the same role since 1955, almost like a Broadway star who refuses to age out of their part. The LDP, or Liberal Democratic Party, has dominated Japanese politics so thoroughly that you might wonder if the electorate ever really had a choice. They didn’t always rule flawlessly—far from it—but like any long-running soap opera, people keep tuning in because it’s what they know. Japan has effectively been a one party democracy so long they make Singapore look like France.

[image error]

[image error]1. 1955 – LDP Founded:

The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was established in 1955 and has been a dominant political force in Japan. The founders included Kodama Yoshio, a war criminal and yakuza associate, who used yakuza money to bankroll the party. Also, Kishi Nobusuke, the grandfather of later Prime Minister Shinzo Abe–also a war criminal who was unfortunately not executed but returned to power by the US government. He was also neck deep in ties to violent right-wing groups and organized crime (yakuza). The CIA funded the party and its leaders as well. (Yes, not kidding). This marked the beginning of a long period of LDP control over the government, often referred to as the “1955 system,” in which the party maintained a near-unbroken rule for decades.

2. 1993 – Non-LDP Coalition Government:

In 1993, the LDP briefly lost power when a coalition of opposition parties formed a government, marking a rare break from LDP dominance.

3. 1994 – LDP Returns to Power:

The LDP regained power in 1994, forming a coalition with the Socialist Party and other smaller parties. This period marked a return to their long-standing political influence.

4. 2009 – Democratic Party Government:

In 2009, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) won a historic election, ending decades of LDP dominance. This shift was seen as a major political upheaval, but the DPJ government faced challenges during its rule.

5. 2012 – LDP Returns to Power:

In 2012, the LDP, led by Shinzo Abe, returned to power in a coalition with the Komeito Party. This marked the re-establishment of LDP dominance, which has continued into the present.

Here’s the same info with a little more context.

1955 – The LDP Debut:

The LDP’s first appearance on the political scene was in 1955, when they burst onto the stage as the supposed defenders of post-war Japan. You can picture the party as a kindly uncle who’s good at fixing things but terrible at innovation. Stability was the name of the game. For decades, the LDP controlled the government like a well-rehearsed play, while the opposition bumbled about like understudies who barely knew their lines.

1993 – A Brief Intermission:

In 1993, something truly shocking happened: the LDP lost power. I imagine the party heads must’ve reacted like aging prima donnas who were asked to share the spotlight. The non-LDP coalition government that took their place didn’t last long—sort of like a new director coming in to “shake things up” before being promptly fired.

1994 – Return of the LDP:

By 1994, the LDP was back in charge, as if nothing had happened. They even brought along the Socialist Party, like an old frenemy you can’t quite get rid of. The LDP came back with a swagger, but their routine hadn’t changed. They were still the same old uncle, good at keeping things stable, terrible at innovation.

2009 – A New Actor on Stage:

Then, in 2009, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) managed to steal the spotlight. Everyone thought the show was going to change forever—new ideas, new faces! But it turns out the DPJ was more like a one-hit wonder than a star in the making. They stumbled, they fumbled, and by 2012, the LDP was back, pulling off a political comeback worthy of Cher.

2012 – Shinzo Abe and the Return of the LDP:

Enter Shinzo Abe, stage left. Abe didn’t just want stability; he wanted Abenomics . Now, if Abenomics were a play, it would have opened with great fanfare, only to close after a disastrous first act. You see, Abe had big dreams of economic growth and revitalization through his “three arrows” policy—fiscal stimulus, monetary easing, and structural reforms. Sounds promising, right? Except the arrows mostly missed their mark. Abe managed to weaken the yen and pump up the stock market, but wage growth remained stagnant, and Japan’s economy didn’t quite get the revival it was promised. It was like promising the audience fireworks and delivering sparklers.

But economic failure wasn’t enough to bring Abe down. Oh no, this was a man with staying power, though not necessarily for the right reasons.

Abe’s Corruption and Scandals:

One of Abe’s less savory legacies was his knack for avoiding scandals by simply ignoring them. Take, for instance, the 2017 Moritomo Gakuen scandal, which involved his wife and an ultra-nationalist school getting a sweetheart deal on government land. That was followed by the Kake Gakuen scandal, where Abe’s office allegedly pulled strings to benefit a friend’s veterinary school. These scandals were like bad reviews that just wouldn’t go away, and yet, Abe held onto power with the tenacity of a star who refuses to leave the stage.

Abe’s particular pièce de résistance in the scandal department involved the infamous slush fund tied to his faction. Millions of yen, allegedly funneled into secret accounts for personal and political favors, as if his political career were some kind of mafia movie where everyone has a price. He managed to sidestep this one too, making a quick bow and walking off-stage before any real damage could be done.

Blocking the Shiori Ito Investigation:

Then there’s the issue of Shiori Ito, the journalist who accused a powerful broadcaster, Noriyuki Yamaguchi, of rape. Abe’s government didn’t just mishandle the case; they effectively buried it. Yamaguchi was a close associate of Abe, and any thorough investigation into the case was promptly halted. Ito fought back and eventually won a civil case, but not before the government’s indifference (and let’s be honest, complicity) became painfully obvious. Abe had turned Japan’s justice system into an old boys’ club where the members cover each other’s backs.

The Enduring LDP Dynasty:

And yet, despite all of this—Abenomics’ failure, the corruption scandals, the disgraceful handling of sexual assault allegations—Abe and the LDP endured. After Abe stepped down in 2020, the LDP continued to hold power, as if they were the default setting on Japan’s political remote control.

So here we are in 2024, with the LDP still firmly at the helm. It’s like watching a production that’s been running for 70 years—you’ve seen all the plot twists, but you keep buying tickets because, well, what else is there? It’s hard to say whether this political theater will ever end, but for now, the show goes on.

2024 Election Results

2024 House of Representatives Election

• LDP (Liberal Democratic Party): 191 seats secured (132 in constituencies and 59 in proportional representation).

• CDP (Constitutional Democratic Party): 148 seats secured (104 in constituencies and 44 in proportional representation).

• JIP (Japan Innovation Party): 38 seats secured.

• DPFP (Democratic Party for the People): 28 seats secured.

• KM (Komeito): 24 seats secured.

• RS (Reiwa Shinsengumi): 9 seats secured.

• JCP (Japanese Communist Party): 8 seats secured.

• ST (Socialist Party): 3 seats secured.

• SDP (Social Democratic Party): 1 seat secured.

• TCP (Tokyo Citizens Party): 0 seats secured.

• Other: 3 seats.

• Independent candidates: 12 seats.

*In Japan, during elections, people fill out two ballots. One for the candidate in their region and another voting for a political party. The number of party votes determines a certain number of representatives the party gets in office. The roster created by the party gives a chance for politicians who lose “the popular vote” to still stay in office or be put there in the first place. The names of the candidates and party must be handwritten.

Corruption, Cults, and Collapse: Voters Reject Japan’s Ruling Party in Major Election Blow

The sins of deceased ex-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe: the slush fund, the failed economic policies, and the ties to the unification church came back to haunt his party.

The sins of deceased ex-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe: the slush fund, the failed economic policies, and the ties to the unification church came back to haunt his party. In a not-so-surprising twist that has Japan’s ruling party licking its wounds, the 2024 lower house election results show the ruling coalition crumbling to pieces. After decades of near-uninterrupted dominance since 1955, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)–which is neither liberal nor democratic–couldn’t escape the weight of its own corruption scandals, failed economic policies, and, perhaps most damningly, its ties to the Unification Church, a group detested by the Japanese public. You won’t hear the Japanese press write much about that aspect of their losses, because the church has begun suing newspapers and media critical of their activities.

The LDP and their coalition partner Komeito needed 233 seats to hold onto power–they ended up with 214. The LDP itself shrank to 191 seats and their staunchly liberal opposition, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan scored 148, making them the largest opposition party in the lower house of Japan’s Parliament.

The Liberal Democratic Party is composed of many different factions, much like the Yamaguchi-gumi, Japan’s largest yakuza group (founded in 1915) also has various factions vying for power.

The de facto Abe faction, once the shining star of the party, has been irreparably tainted–and were the biggest losers. Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s assassination in 2022 was a political earthquake, but the revelations that followed shook the LDP to its core. Turns out, the beloved leader wasn’t just working on behalf of the people; he and his inner circle were knee-deep in shady dealings with the notorious Unification Church, a group reportedly known for exploiting its members and funneling cash into political coffers.

Economically, the so-called success of Abenomics, which was supposed to lift Japan from its decades-long stagnation, has been revealed to be largely smoke and mirrors—based on falsified data. What it left behind was a gaping wealth gap, inflation that made daily life increasingly difficult, and wages that hadn’t budged in years. Former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida promised to change gears but kept the same failed policies in place. The people of Japan had simply had enough.

This election isn’t just a loss for the LDP; it’s a referendum on a political system that’s been slowly eroding. The rise of the opposition, led by the CDP with 148 seats, signals a shift in public sentiment. Parties like the Japan Innovation Party (JIP) and the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) are now positioned to play larger roles in shaping Japan’s future.

The LDP’s downfall can be seen as a microcosm of the failures plaguing long-standing political regimes worldwide: arrogance, corruption, and an inability to adapt to the needs of a changing society. When power is too concentrated for too long, it begins to rot from the inside out.

The unholy alliance between the LDP and the Unification Church was just the tipping point. This election marks a dramatic turn in Japanese politics, one that may finally bring the long-simmering dissatisfaction with the ruling party to a boil.

The Fall of Hakubun Shimomura Is A Microcosm Of The Greater Problem

In what can only be described as a fall from grace too ironic to script, Hakubun Shimomura, a former education minister, has found himself on the wrong side of a ballot box. After nine consecutive terms in the Tokyo 11th district, Shimomura lost his seat to Yukihiko Akutsu of the Constitutional Democratic Party, and if you’re inclined to celebrate underdog victories, hold your applause—there’s more than just a campaign gaffe or two at play here.

The 70-year-old Shimomura, once a darling of the political elite, couldn’t withstand the mounting scandals that had come to define his career like the pins in a voodoo doll. His name is inextricably linked to an “envelopes-under-the-table” type of affair—let’s call it the “Secret Cash Scandal” (see below). And when you’ve got a moniker like that hanging over you, even the most forgiving electorate starts to ask uncomfortable questions. He had been banned from running on the LDP’s proportional representation list, the political equivalent of being put in the corner with a dunce cap.

There’s something so textbook about his fall, a perfect encapsulation of what happens when the political machine that got you to the top starts churning in reverse. Shimomura is not the only LDP politician whose career has been sabotaged by scandals like these, but his trajectory feels almost like a satire of itself. The former Minister of Education, was once linked to a yakuza associate—who specialized in running school-girl themed sex-shops. He promised to investigate the links between the vice-chairman of Japan’s Olympic Committee and the Yamaguchi-gumi (yakuza group) and then buried the investigation.

He’s the guy who survived nearly three decades of political intrigue, only to be unseated in the twilight of his career by a candidate who spent the better part of two years languishing in relative obscurity. The only thing missing from the narrative is a Greek chorus chanting, “We told you so!”

To add to the irony, Shimomura had been one of the key figures connected to the controversy surrounding the Unification Church, the religious organization formerly known as the Moonies. If you recall, it was his office that oversaw the approval of the group’s name change back in 2015. At the time, it probably seemed like a small procedural matter, but in hindsight, it was the kind of thing that sticks to your political record like gum on a shoe. The ties to the Unification Church not only haunted his campaign but turned the public perception of him into that of a shady backroom dealer—a villain too out of touch to be reformed.

Throughout the campaign, Shimomura made quite the spectacle of apologizing, visiting over 8,000 homes in what one could call his “sincerity tour.” Picture him with his head bowed, muttering apologies like a fallen samurai seeking redemption. It’s a dramatic image, but it wasn’t enough. Shimomura was seen as the embodiment of the LDP’s worst habits—backroom deals, cozying up to questionable organizations, and a blatant disregard for transparency, all of which have soured the electorate’s taste for the party.

These types of scandals are not isolated incidents but rather emblematic of a larger systemic rot within the political hierarchy. Shimomura’s fall is just one more example of the self-inflicted wounds the LDP has suffered, and it raises the question of whether these political titans ever learn. It’s not the scandals themselves that take politicians down, but rather the perception of arrogance and invincibility that seems to precede their downfall.

If we zoom out, Shimomura’s defeat isn’t just about one man’s loss. It’s a microcosm of the deeper issues the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (and frankly, many parties around the world) face in trying to retain the public’s trust while navigating their own internal chaos. The public may forgive a mistake or two, but when the perception of corruption becomes the rule rather than the exception, well, voters decide it’s time for a change.

Their coalition partner, Komeito, didn’t fare well either. Komeito is the political arm of the buddhist organization Soka Gakkai which some have called a cult. It was revealed this year that their spiritual leader, Ikeda Daisaku–who had not been seen in public for over a decade–was actually dead. When he really died, no one knows. Ikeda vanished from public view around the time former Yamaguchi-gumi yakuza boss, Tadamasa Goto, published his biography Habakaringara. In that book, he bragged that he had been doing the dirty work for Soka Gakkai and Ikeda for decades.

The Curse of Shinzo Abe

To truly understand the political implosion of Hirofumi Shimomura and his comrades in this election, you have to consider the broader context of the collapse of the Abe faction and the wreckage left in its wake. For nearly a decade, Shinzo Abe and his loyalists operated with the confidence of autocrats, not just running Japan, but crushing dissent, controlling narratives, and scandalizing the political system like it was part of the job description. Abe himself, until his shocking assassination, wielded immense power behind the scenes, often suppressing freedom of the press and/or corrupting top dogs in the media by wining and dining them. But what finally broke through that iron grip was a revelation so insidious that even Japan’s famously forgiving electorate had had enough.

After Abe’s assassination, the floodgates opened, and it became clear that the prime minister—along with many high-ranking members of the LDP—had been intimately connected with the Unification Church. Yes, that Unification Church, the religious group (or, as most people in Japan prefer to call it, a cult) that has been despised for decades. The fact that Abe and his cronies were not just affiliated with the group but in bed with them on a scale that made voters’ skin crawl sent shockwaves through the nation. It wasn’t just bad optics—it was the epitome of the kind of shady backroom deals that defined the Abe era.

If you’re a student of history, you know that the Liberal Democratic Party was founded with yakuza money by war-time profiteer, Kodama Yoshio and war-criminal Nobosuke Kishi, Abe’s grandfather. From bad seeds, bad things grow. . What should be pointed out is that Abe’s folly wasn’t just a case of a politician playing footsie with an unsavory organization—it was emblematic of the entire Abe faction’s disdain for transparency and democracy. He also cuddled up to sexist right-wing cult, Nippon Kaigi, which opposes many policies that the majority of the Japanese public supports. , But it was the Unification Church link that really damaged his legacy. In fact, his assassin targeted Abe precisely to bring those ties to light. By the time Kishida decided to give Abe a lavish state funeral, 80% of the public opposed the waste of money.

With the public now acutely aware of just how deeply the LDP had been corrupted by its dealings with the Unification Church, the house of cards began to collapse.

As Shimomura learned the hard way, you can only apologize for so long before voters stop listening. His relentless campaign of mea culpas—visiting 8,000 homes to personally apologize—seems quaint when stacked up against the larger issues haunting the LDP. People weren’t just angry at him; they were angry at the system that allowed someone like him to stay in power for nearly three decades.

Abe’s so-called economic success—Abenomics—was supposed to be his legacy. But in reality, it was a carefully crafted mirage built on falsified data from the government. The very foundation of Japan’s economic recovery during his tenure was shaky at best, propped up by manipulation and spin. Wages stagnated, inflation soared, and the gap between rich and poor grew ever wider. Those at the top saw the benefits, while millions were left in a limbo of rising costs and shrinking opportunities. And as Shimomura’s loss shows, voters have reached their breaking point.

This election has been a reckoning not just for Shimomura, but for anyone associated with the Abe faction. Across the board, candidates tied to Abe have fared poorly. His assassination may have removed the man, but the shadow of his scandals, his connections to the Unification Church, and his autocratic tendencies lingers, leaving the LDP scrambling to find a new identity amid the debris.

Shimomura’s downfall is symbolic of what happens when a party—and a political faction—becomes too comfortable in its own corruption. The people of Japan, facing rising inflation, stagnant wages, and an ever-widening wealth gap, have had enough. The LDP has been in power for so long that it forgot it was supposed to serve the public, not control it. And now, as the Abe era truly comes to a close, Shimomura and other Abe cronies are left standing on the street, microphones in hand, wondering where it all went wrong.

Anpanman isn’t stupid: Ishiba’s Power-Play

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has a strange following among Japanese women who think he’s cute, like a mascot. He does resemble Anpan-man, the pastry hero beloved by children. But he’s not a child. At the heart of the LDP’s electoral implosion was a bold move by the current Prime Minister and former defense minister, whose power-play may have gone unnoticed by many. Ishiba, perhaps sensing that the political tides were turning, refused to grant party backing to LDP candidates who had been caught red-handed in the political funds scandal. More notably, he barred these scandal-tainted figures from being listed on the proportional representation roster*, the lifeboat that could have saved many from their inevitable loss in single-seat elections. Without this safety net, politicians like Hirofumi Shimomura found themselves stranded.

Ishiba’s strategy was clear: cut the party’s losses and purge the taint of corruption, even if it meant temporarily weakening the LDP’s grip on power. It was a calculated gamble, one that not only distanced the party from its most scandal-ridden figures but also conveniently eliminated many of his own political rivals within the LDP. The result? A weakened party, stripped of its old guard, and left to face an emboldened opposition. In the short term, this maneuver accelerated the LDP’s downfall and handed a decisive victory to the opposition. Whether this will be remembered as a tactical masterstroke that ultimately saved the party, or the final nail in the coffin of the Abe-era LDP, remains to be seen.

Results

2024 House of Representatives Election

• LDP (Liberal Democratic Party): 191 seats secured (132 in constituencies and 59 in proportional representation).

• CDP (Constitutional Democratic Party): 148 seats secured (104 in constituencies and 44 in proportional representation).

• JIP (Japan Innovation Party): 38 seats secured.

• DPFP (Democratic Party for the People): 28 seats secured.

• KM (Komeito): 24 seats secured.

• RS (Reiwa Shinsengumi): 9 seats secured.

• JCP (Japanese Communist Party): 8 seats secured.

• ST (Socialist Party): 3 seats secured.

• SDP (Social Democratic Party): 1 seat secured.

• TCP (Tokyo Citizens Party): 0 seats secured.

• Other: 3 seats.

• Independent candidates: 12 seats.

*In Japan, during elections, people fill out two ballots. One for the candidate in their region and another voting for a political party. The number of party votes determines a certain number of representatives the party gets in office. The roster created by the party gives a chance for politicians who lose “the popular vote” to still stay in office or be put there in the first place. The names of the candidates and party must be handwritten.

Election Update: Japan’s Ruling Party Looks Likely to Lose Majority and finds out karma is a bitch.

As the ballots trickle in from Japan’s general election, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) —which is infamously neither liberal nor democratic–is having the kind of night you wouldn’t wish on your worst enemy. The party has ruled Japan, almost uninterrupted since 1955. They briefly lost power in 1993 and were soundly trounced by the Democratic Party of Japan (the predecessor to the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan) in 2009 before regaining power in 2012.

Some major power brokers in the party took a hit tonight. Amari Akira, a former LDP Secretary-General, has been ceremoniously dethroned in Kanagawa’s 20th district, where Otsuka Sayuri of the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) danced on the grave of his political career. And it gets worse if you’re a member of the LDP Abe faction. Tokyo, the LDP’s once-proud bastion, is now slipping into opposition hands like it’s hosting a fire sale. Shimomura Hakubun, former education minister with rumored ties to yakuza associates, and Marukawa Tamayo, both with enough scandal under their belts to merit Netflix miniseries, are expected to lose their seats to CDP candidates.

The LDP’s Titanic? Let’s hope so. Prime Minister Ishiba, decided not to provide life boats to politicians caught in the slush fund scandal (see below), many who belonged to the faction of his lifelong enemy, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (RIP). They didn’t get official LDP support in the election nor did they get a chance to survive political death by being put on the proportional representation ballot either.

By 8 PM, the polls had closed, and the predictions were grim. Exit polls suggest the LDP is unlikely to retain its majority, wobbling somewhere between 153 and 219 seats, far short of the necessary 233. Meanwhile, the CDP is looking chipper, poised to nab between 128 and 191 seats—likely on the back of voter fury over a cost-of-living crisis that even the most oblivious politicians can’t ignore. Komeito, the LDP’s wingman in governing Japan, might also lose seats, leaving the coalition frantically paddling just to stay afloat. They are suffering from the recent death of their defacto leader, Soka Gakkai guru Daisaku Ikeda, who may have actually been dead for years.

What does this all mean? If the LDP loses its majority, we might actually see a Japan where someone other than a scandal-saddled, cronyism-filled, sleepwalking juggernaut runs the show. Imagine that. It could mean real checks on government power, maybe even policies that acknowledge the existence of normal people. But more than anything, it would mean a well-deserved comeuppance for a party that’s been weighed down by bad press, worse policies, and ties to organizations that should probably come with a disclaimer.

Now for some fun background:

The “slush fund scandal” was primarily composed of LDP members—most notably from the Abe Shinzo faction—being caught with their hands deep in the political cookie jar. Money flowed in unsavory directions, and it wasn’t long before voters started asking questions like, “Hey, why does my representative not pay taxes on the millions of yen he gets in his slush fund?” The Japan Communist Party newspaper Akahata, actually broke the story. Then there’s the Unification Church saga, brought to light after Abe Shinzo’s assassination in 2022. It turns out, a number of LDP members had cozy relationships with the cult, which made voters, incensed. It’s not every day that an assassination uncovers ties to a shadowy religious group, but welcome to Japanese politics.

October 26, 2024

The elections in Japan 101 : regime change or LDP 🎉 party

Imagine Japan as a stage and the LDP as the lead actor, playing the same role since 1955, almost like a Broadway star who refuses to age out of their part. The LDP, or Liberal Democratic Party, has dominated Japanese politics so thoroughly that you might wonder if the electorate ever really had a choice. They didn’t always rule flawlessly—far from it—but like any long-running soap opera, people keep tuning in because it’s what they know. Japan has effectively been a one party democracy so long they make Singapore look like France.

[image error]

[image error]1. 1955 – LDP Founded:

The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was established in 1955 and has been a dominant political force in Japan. This marked the beginning of a long period of LDP control over the government, often referred to as the “1955 system,” in which the party maintained a near-unbroken rule for decades.

2. 1993 – Non-LDP Coalition Government:

In 1993, the LDP briefly lost power when a coalition of opposition parties formed a government, marking a rare break from LDP dominance.

3. 1994 – LDP Returns to Power:

The LDP regained power in 1994, forming a coalition with the Socialist Party and other smaller parties. This period marked a return to their long-standing political influence.

4. 2009 – Democratic Party Government:

In 2009, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) won a historic election, ending decades of LDP dominance. This shift was seen as a major political upheaval, but the DPJ government faced challenges during its rule.

5. 2012 – LDP Returns to Power:

In 2012, the LDP, led by Shinzo Abe, returned to power in a coalition with the Komeito Party. This marked the re-establishment of LDP dominance, which has continued into the present.

Here’s the same info with a little more context.

1955 – The LDP Debut:

The LDP’s first appearance on the political scene was in 1955, when they burst onto the stage as the supposed defenders of post-war Japan. You can picture the party as a kindly uncle who’s good at fixing things but terrible at innovation. Stability was the name of the game. For decades, the LDP controlled the government like a well-rehearsed play, while the opposition bumbled about like understudies who barely knew their lines.

1993 – A Brief Intermission:

In 1993, something truly shocking happened: the LDP lost power. I imagine the party heads must’ve reacted like aging prima donnas who were asked to share the spotlight. The non-LDP coalition government that took their place didn’t last long—sort of like a new director coming in to “shake things up” before being promptly fired.

1994 – Return of the LDP:

By 1994, the LDP was back in charge, as if nothing had happened. They even brought along the Socialist Party, like an old frenemy you can’t quite get rid of. The LDP came back with a swagger, but their routine hadn’t changed. They were still the same old uncle, good at keeping things stable, terrible at innovation.

2009 – A New Actor on Stage:

Then, in 2009, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) managed to steal the spotlight. Everyone thought the show was going to change forever—new ideas, new faces! But it turns out the DPJ was more like a one-hit wonder than a star in the making. They stumbled, they fumbled, and by 2012, the LDP was back, pulling off a political comeback worthy of Cher.

2012 – Shinzo Abe and the Return of the LDP:

Enter Shinzo Abe, stage left. Abe didn’t just want stability; he wanted Abenomics . Now, if Abenomics were a play, it would have opened with great fanfare, only to close after a disastrous first act. You see, Abe had big dreams of economic growth and revitalization through his “three arrows” policy—fiscal stimulus, monetary easing, and structural reforms. Sounds promising, right? Except the arrows mostly missed their mark. Abe managed to weaken the yen and pump up the stock market, but wage growth remained stagnant, and Japan’s economy didn’t quite get the revival it was promised. It was like promising the audience fireworks and delivering sparklers.

But economic failure wasn’t enough to bring Abe down. Oh no, this was a man with staying power, though not necessarily for the right reasons.

Abe’s Corruption and Scandals:

One of Abe’s less savory legacies was his knack for avoiding scandals by simply ignoring them. Take, for instance, the 2017 Moritomo Gakuen scandal, which involved his wife and an ultra-nationalist school getting a sweetheart deal on government land. That was followed by the Kake Gakuen scandal, where Abe’s office allegedly pulled strings to benefit a friend’s veterinary school. These scandals were like bad reviews that just wouldn’t go away, and yet, Abe held onto power with the tenacity of a star who refuses to leave the stage.

Abe’s particular pièce de résistance in the scandal department involved the infamous slush fund tied to his faction. Millions of yen, allegedly funneled into secret accounts for personal and political favors, as if his political career were some kind of mafia movie where everyone has a price. He managed to sidestep this one too, making a quick bow and walking off-stage before any real damage could be done.

Blocking the Shiori Ito Investigation:

Then there’s the issue of Shiori Ito, the journalist who accused a powerful broadcaster, Noriyuki Yamaguchi, of rape. Abe’s government didn’t just mishandle the case; they effectively buried it. Yamaguchi was a close associate of Abe, and any thorough investigation into the case was promptly halted. Ito fought back and eventually won a civil case, but not before the government’s indifference (and let’s be honest, complicity) became painfully obvious. Abe had turned Japan’s justice system into an old boys’ club where the members cover each other’s backs.

The Enduring LDP Dynasty:

And yet, despite all of this—Abenomics’ failure, the corruption scandals, the disgraceful handling of sexual assault allegations—Abe and the LDP endured. After Abe stepped down in 2020, the LDP continued to hold power, as if they were the default setting on Japan’s political remote control.

So here we are in 2024, with the LDP still firmly at the helm. It’s like watching a production that’s been running for 70 years—you’ve seen all the plot twists, but you keep buying tickets because, well, what else is there? It’s hard to say whether this political theater will ever end, but for now, the show goes on.

October 24, 2024

Update: Tigran Gambaryan, American Hero and Good Guy is Free!

October 24th 2023

TIGRAN GAMBARYAN LEAVES NIGERIA AFTER 8 MONTHS UNLAWFUL DETENTION

October 23rd, 2024

Today, American citizen Tigran Gambaryan left Nigeria to return home to his family after eight months of unlawful detention. The charges brought against him by the Nigerian Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) were dropped in court in Abuja yesterday. The EFCC prosecutor stated in court: “The government has reviewed the case and, taking into consideration that the second defendant (Mr. Gambaryan) is an employee of the first defendant (Binance Holdings Limited), whose status in the matter has more impact than the second defendant’s, and also taking into consideration some critical international and diplomatic reasons, the state seeks to discontinue the case against the second defendant.” Tigran was released from Kuje prison last night. Tigran’s health has suffered significantly while in prison, and he will now finally receive the medical attention he desperately requires. Tigran’s wife, Yuki Gambaryan, has released the following statement: “It is a huge relief that this day has finally come. The past eight months have been a living nightmare. I wish it hadn’t taken this long for his release, or that his health had not declined so much, but we can now focus on healing as a family. I want to express my deepest gratitude to the US government for their efforts in securing his release. I also want to thank everyone who helped us throughout this ordeal. There were moments I feared this day would never come, but Tigran’s supporters gave me hope and strength. The road ahead for Tigran’s recovery is going to be difficult, and I appreciate us being given the time and space to focus on that. Our children cannot wait to see their dad again.”

Editor’s note: I spoke to Tigran today from his hotel in Rome. He was flown out of Nigeria on a swanky airplane. The first time he’s been on a private jet in his life. I think he’s allowed to have a carbon footprint this time around. After a lively debate about whether malaria or liver cancer is the best way to lose weight, we chatted some more. As you’re reading this, hopefully he’s enjoying pizza and beer with some other 1811s on vacation.

PREVOUS ARTICLE BELOW (APRIL 2024)

As April 2nd dawns, a new month brings the promise of spring, with temperatures on the rise. Yet, amidst this renewal, there’s still no positive news on the unjust confinement of former Special Agent Tigran Gambaryan and Nadeem Anjarwalla, high-ranking employees at Binance. Tigran, a US citizen, led Financial Crime Compliance, while Nadeem, a citizen of Kenya and the UK, represented Binance in East and West Africa.

Free Tigran

Since February 26th, the two Binance executives have been detained by Nigerian authorities in a guest house room, their reasons for detention shrouded in mystery. Yet, their affiliation with Binance, a major cryptocurrency exchange, hints at a connection. Nigerian authorities have been aggressively targeting cryptocurrencies, ostensibly to salvage the national currency from total collapse. Seemingly at the cost of sacrificing the individual freedoms of innocent people.

Dispatched to Nigeria on February 25 by their company, Tigran and Nadeem were on a mission: to hold official meetings and negotiate common ground with authorities. Their goal? To address the fallout from the Nigerian government’s decision to cut off crypto companies from telecom giants. However, their mission took a dark turn. Instead of engaging in verbal negotiations, they found themselves in an unexpected role: hostages for the Nigerian government, evidently used as bargaining chips to pressure crypto companies into compliance.

Confined to a room without charges and stripped of their passports, Tigran and Nadeem’s freedom hangs by a thread. With no clear answers and uncertainty about their governments’ efforts to secure their release, they remain in limbo. Despite the Nigerian court’s approved 14-day detention period for further investigations, which expired almost a month ago, there’s been no sign of the authorities changing course.

While the world marches on outside their confined room, Tigran and Nadeem’s families are stuck in the agonizing moment they learned of their unjust detention. Their wives fight tirelessly for their release, longing for the day they can reunite. These devoted husbands and fathers are robbed of precious moments with their loved ones. Above all, the Nigerian authorities seem to have overlooked a fundamental truth — they are human beings. Their lives shouldn’t be gambled in a political game they never signed up for.

Tigran’s wife, Yuri Gambaryan, has launched a new petition demanding freedom for her husband and his colleague. Every signature counts, bringing their plight to the attention of US officials and exerting pressure for prompt action. With increased pressure, there’s a greater chance of freeing these innocent men from their 40-day unjust confinement. Let’s ensure they reunite with their families where they rightfully belong. Sign the petition and amplify Tigran and Nadeem’s families’ voices!

October 15, 2024

Protected: The Department Of Sickness And Death

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

October 12, 2024

Ex-Mt. Gox CEO eyes crypto for all with new initiative EllipX, Japan slow to get on board

Yesterday the former CEO of infamous Tokyo-based cryptocurrency exchange Mt. Gox announced the release of a new crypto initiative. The new company, called EllipX (pronounced “el-ip-ex”), consists of the EllipX Wallet and the EllipX Exchange.

French Bitcoin veteran and Tokyo resident Mark Karpeles promises that his latest entrepreneurial venture will provide products that are more secure and accessible than other cryptocurrency tools currently on the market.

Old problems, new solutionsThe issue of security is all too familiar to Karpeles. His announcement comes a decade after one of the biggest scandals in Bitcoin’s history, where approximately 850,000 bitcoin were stolen from Mt. Gox. Mt. Gox, helmed by Karpeles in 2011, was the largest Bitcoin exchange by volume at the time. Karpeles is still considered an early pioneer in the industry.

Cryptocurrency has long been plagued by the problem of balancing user experience and security. Even the most basic component—being able to access your tokens—is something the industry has yet to figure out an elegant solution for. Karpeles says, “When you first start out in crypto, they ask you to write [the full crypto key] on an ordinary piece of paper and protect it with your life…it’s not the best user experience.”

Using Multi-Party Computation (MPC), Karpeles developed a system that allows the user to set up the wallet in a similar way to mobile banking, eliminating the risk and clunky user experience associated with traditional cryptocurrency management. The value of this new technology and other emerging technologies is not lost on Karpeles, claiming, “If MPC had existed at the time of Mt. Gox, the bankruptcy wouldn’t have happened.”

“There’s nothing to write on paper, it’s actually a lot safer.”

Learning from the pastMt. Gox was unable to recover from the hacking, and filed for bankruptcy in 2014. Since then, Karpeles has been in a lengthy process of repaying users who had lost some or all of their bitcoin balances during the downfall of the platform. Users are in luck; due to the rise in value of Bitcoin, many creditors were able to recover many times more the value of their initial holdings.

“After Mt. Gox I didn’t expect to be involved in crypto again, but I’ve had a lot of people from the industry…telling me to come back and make use of the experience I’ve accumulated with Mt. Gox.”

“I believe it’s time for me to turn the page and use the experience to make things more user friendly and more secure in the crypto industry.”

Japan’s uncertain future in cryptocurrencyThe crypto industry is booming globally, and Karpeles and others are keen on making cryptocurrency as easy as managing a checking account. However, there is at least one country that conspicuously doesn’t share this goal: Karpeles’ adoptive home country, Japan.

EllipX will not be available in Japan due to how the country has been handling crypto license applications. “You can apply for a license, and there’s a lot of applications that were made in the last 6 to 8 years, but none have been approved,” says Karpeles.

Not only have they not been approved, but many applications fail to get any response at all.

“My strength alone, or only one company pushing [for regulations to be more open in Japan] is not going to be enough, but I do know there are others, so we will continue pushing into that direction.“

September 19, 2024

Win a copy of The Last Yakuza

The Last Yakuza

The Last Yakuzaby Jake Adelstein

Giveaway ends October 04, 2024.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

August 16, 2024

The Real-Life Kamurochō: A Yakuza History Lesson with Tokyo Noir’s Jake Adelstein

The Real-Life Kamurochō: A Yakuza History Lesson with Tokyo Vice’s Jake Adelstein

We explore Tokyo’s Kabukicho, the inspiration behind the central setting of the series formerly known as Yakuza. (originally published on GameInformer.com)

By Marcus Stewart on July 3, 2023, at 2:00 PM

It’s an uncomfortably humid night in the bustling Shinjuku ward of Tokyo, Japan. I futilely try to circulate air in my sweat-stained shirt at an intersection surrounded by questionable bars and seedy nightclubs. A comparatively innocent landmark grabs my attention: a batting center. It’s a delightfully familiar sight. But as I imagine its visitors enjoying a fun day swinging for the fences, author Jake Adelstein pops my thought bubble by telling me that the most horrific gang violence he ever witnessed unfolded on the corner we stand on: someone cracking another person’s skull open with a baseball bat.

Kabukichō has a notorious, bloodstained history due to its long-standing role as host to yakuza and other gangs. It’s also the inspiration for Kamurochō, the famous open world from the Yakuza series (now globally rebranded as Like A Dragon). Though the games don’t shy away from that violent reputation, the semi-heroic portrayals of characters Kiryu and Ichiban Kasuga, along with the games’ trademark silliness, make it easy to forget that the yakuza are objectively the bad guys, responsible for a number of horrific deeds. In the real world, that includes, among other things, murder, human trafficking, and various forms of extortion. A good number of those crimes occurred within Kabukichō’s alleys. This city’s bright lights can blind visitors to its dark past.

From Swamp To Adult Entertainment Epicenter

From Swamp To Adult Entertainment EpicenterKabukichō is located in Tokyo’s Shinjuku ward and sits on what was once a swamp called Tsunohazu. In the 1920s, urban development began, and Tsunohazu hosted many foreign-owned businesses. The most notable establishment was the “Tsurekomi Yado” or “Tsurekomi Inns,” predecessors to the modern love hotels, private establishments providing discreet venues for sexual encounters charged hourly or nightly, that would later define Kabukichō. Heavy bombing during World War II devastated Tsunohazu, prompting its reconstruction as a theater district centered around a planned Kabuki theater with the new name of Kabuki-chō. Financial setbacks killed this plan, however, but the name stuck.

In the 1950s, Kabukichō morphed into an entertainment venue with recreational hot spots such as movie theaters, skating rinks, and traditional theaters. The district’s first host club, nightclubs where waitstaff provides conversation and drinks to patrons under the guise of dates, Club Ai, opened in 1971. This ushered a wave of adult entertainment that flooded the area in the following decades. By the new millennium, Kabukichō was Asia’s largest adult entertainment area. It now features thousands of bars, nightclubs, host clubs, love hotels, and massage parlors, earning its nickname the “Sleepless Town.” As Jake tells us, “Traditionally, everything in this area was about getting sexual services. And maybe drinking cheaply.”

The Yakuza’s Rise And Decline

The Yakuza’s Rise And DeclineDespite our destination, our journey begins rather innocently at a local Krispy Kreme. After meeting Jake and fueling up on donuts and coffee, we make the short trek down the bustling streets. Although several roads lead to the district, the flashiest and most recognizable entrance is Kabukichō Ichiban Machi (translated as Kabukichō 1st Avenue), the red neon arch immortalized in multiple Yakuza titles. Seeing it in person is a treat, and passing under it feels like entering a portal into the games themselves.

Kabukichō assaults the senses. Illuminated signs and billboards advertising the hottest hosts, unsettlingly attractive idols, various clubs, and more adult services plaster every wall space. Throughout our tour, young women donned in skimpy costumes, such as maids or schoolgirls, solicit us with flyers promoting their respective hostess clubs. On several occasions, bar employees attempt to coax us into their establishments with (often false) promises of cheap drinking prices. We spy one particular bar blatantly advertising additional, shall we say, adult pleasures, making Adelstein remark, “That is one of the most provocative bar signs Iʼve ever seen. Iʼm surprised the police havenʼt busted this place.”

Adelstein’s comment alludes to the fact that the Kabukichō of today is a shell of its former self. As fans have seen in the games, there was a period when the district was regularly patrolled by yakuza enforcers, often in broad daylight, recognizable by their fancy suits, gaudy shirts, and immaculately coifed hair. Gang members collected protection money from businesses, often targeting foreign-owned establishments as they were targets of racial prejudice the police sometimes ignored. Of course, this also meant plenty of street violence as gangs regularly clashed over territory and other disputes. “Back in 1999, there was a lot of fighting gangs,” says Adelstein. “[The police] were always getting calls in the middle of the night. There’s always something happening.”

You can’t even smoke in Kabukicho now

During our walk, I imagine the countless brawls that likely unfolded within its sometimes cramped passageways, obscured from public view or on full display. The violence of the Yakuza games tends to be over-the-top, with players comically swinging large, unwieldy objects, from trashcans to bicycles, to smash attackers. Adelstein has only a cursory knowledge of the franchise (he enjoys them for the sight-seeing aspect more than anything), but he claims to have witnessed several confrontations that would fit right at home in its universe. For example, he says he’s seen a gang member use a bicycle as a weapon. We eventually reach the batting center, a staple destination in the games for players looking to unwind with a goofy activity between missions. Adelstein recalls stumbling upon a yakuza member in a confrontation with a rival on the very corner we stand. Jake is unclear about what they were arguing over, but the exchange escalated to the point where the yakuza grabbed a bat and used his target’s head for batting practice. Adelstein vividly describes the sound of this impact as “like someone dropping a watermelon.”

As scary as that sounds, touring Kabukichō today isn’t quite as dicey as it perhaps was 15 years ago. Government clean-up efforts beginning in the early 2000s sought to reduce yakuza presence in the area and shut down morally questionable establishments, such as brothels and illegal clubs. An estimated 1,000 yakuza members occupied Kabukichō in 2004, but increased police patrols and the installment of surveillance cameras played a big part in pushing them into hiding. These cameras aren’t hidden. I spot several of them during our walk through the district. Law enforcement wants you to know you’re being watched, but it doesn’t stop there.

“In 2005, they revised the organized crime control laws again so that technically just walking together as a group could be a violation […] so you wouldnʼt see [yakuza] out in the wild,” Adelstine says.

We don’t go too far into the night without noticing a cop car or officers patrolling. We actively avoid them because even though we were doing nothing suspicious, as Jake quips, “Maybe theyʼll harass us just because theyʼre bored.”

Despite this pressure, the yakuza aren’t entirely gone from Kabukichō. Adelstein assures us some still linger; they’re just less obvious and nowhere near as numerous. In addition to taking us by an unassuming office building that remains an active yakuza headquarters, Jake invites us to have coffee at Parisienne. This cafe and the surrounding block were once well-known epicenters for yakuza chairmen meetings during what Jake calls “the old days.” Adelstein spent many days here eavesdropping on gang leaders or socializing with others who served as inside sources for his investigations. A kind elderly gentleman serves us, who Jake points out has been working at the cafe for decades, meaning his friendly eyes have witnessed all kinds of crooked dealings unfold in our very seats.

We lower the volume of our conversation; Jake informs us that casually uttering “yakuza” makes people nervous or suspicious, so we refer to them as “businessmen” during our visit. He also teaches us a bit of sign language, running his finger down his face to indicate a scar. Facial scars are telltale signs of a yakuza, as itʼs proof they survived a deadly fight (eventually, many members scarred themselves to appear tougher than they perhaps were), so performing this silent gesture lets people know what you’re talking about.

As we dine, Adelstein explains how the Japanese government’s decades-long crackdown on Kabukichō went hand in hand with the yakuza’s steady decline. In addition to the new laws, he believes many of their struggles have been self-inflicted due to greed. As he puts it, society tolerated the yakuza for so long because they once served a purpose. Many people hired their enforcers to settle civil disputes that traditional courts either dismissed, took ages to settle, or were too weak to enforce a ruling. Yakuza served as the people’s champions in some ways by more effectively solving citizens’ problems. While they were never above crimes such as extortion, blackmail, and bid rigging, they didn’t cross certain lines. That was until some factions became over-ambitious and aggressive, pulling taboo stunts

like evicting people from their homes. Provocative acts like this earned more and more ire from the public and police until they eventually couldn’t be ignored; the hostile actions of a few groups spoiled it for the bunch. The persistent infighting between families means widespread cooperation on big jobs that could benefit all of them has become much harder to pull off.

Besides that, Adelstein claims that yakuza haven’t adapted to modern times. Japan’s increased surveillance society and modern crime-fighting techniques have crippled their ability to operate as effectively as they once had, and a decline in recruitment of younger members has left factions with an aging guard with outdated ideas of how to maintain influence and relevance.

“The average age of your member is 50 years old,” says Adelstein. “Iʼm 53, right? So that would make me like, you know, a senior. You can’t survive as a bunch of gangsters when your average age is 50, man. It’s not getting younger. Anybody who’s smart sees that there’s no future for these guys.”

Kabukichō Today

After finishing our coffees and pastries, we hit the streets once again. It’s late in the evening, and Kabukichō has quieted, with only a handful of passersby making their way home or perhaps searching for an open hole in the wall for one last round. I get a last chance to soak in the area’s current state.

While criminal activity and illicit entertainment defined the Kabukichō of old, the area now primarily promotes selling affection. I probably saw more host clubs than any other business. While some can be relatively innocent (and I’m being generous), Jake warns that the sleaze remains and that visitors, especially women, and tourists, should be wary.

“Some are basically very fraudulent,” Adelstein explains. “Like, they would lure in girls at low prices, and then they keep jacking up the price. And sometimes they jack the price so high […] it’s like, ‘Well, if you can’t pay the bills that you owe,’ then they introduce the girl to a loan shark, which is connected to the host club, and then the host and the loan shark introduce them to a sex shop where they start working to pay off their debt. So, it’s kind of this sinister operation where they basically create indentured servants from their customers.”

We also spot a few pawn stores nearby, which have a symbiotic relationship with host clubs as patrons visit them to buy cheap gifts for their favorite hosts, who often turn around and pawn them right back. While a segment of Japanese youth once aspired to become yakuza, Jake says this has shifted to where perhaps just as many would rather become hosts and hostesses themselves. But the competition is fierce, and it may not even be worth it right now since the business, as a whole, has suffered due to the pandemic and the current weak economy, since patrons, mainly men, have less disposable income to throw at these establishments.

Despite this, Kabukichō has other offerings that don’t involve paying people to pretend they’re attracted to you. Some love hotels have converted into traditional themed inns; we saw some promoting Hawaiian and Indonesian experiences. For those who enjoy drinking, Golden Gai’s tight alleyways, packed with numerous small, intimate bars, can be good for enjoying spirits in a quieter, authentic atmosphere (though some forbid foreigners). I was also surprised when we stumbled upon Hanazono Shrine, a famed 17th-century Shinto Shrine sticking out like a sore thumb amongst modern architecture. Toho Cinema, recognizable by the giant Godzilla statue head looming over it, lets you take in a flick and keep off the streets. Of course, every fan of the Yakuza games must hit the multi-story, 24-hour Don Quixote store.

The ongoing addition of these more innocent attractions and continued crackdown on gangster activity have helped slowly repair Kabukichō’s reputation. But its seedier elements shouldn’t be ignored. Despite clean-up efforts, Kabukichō ranked third on the Tokyo Police Department’s 2019 list of the city’s most dangerous districts based on crime data and had the highest number of violent crimes that year. Strolling the streets as a starry-eyed video game-loving tourist, I was easily swept up in the novelty of stepping into a real version of a world I recognized and enjoyed. A visit isn’t out of the question – Tokyo as a whole is one of the world’s safest cities – as long as you remember where you are and recognize the hidden scars of this former den of debauchery.

Walking through Kabukicho With Marcus Stewart

Walking through Kabukicho With Marcus Stewart This article originally appeared in Issue 354 of Game Informer.

Marcus Stewart

Associate Editor

Marcus is an avid gamer, giant wrestling nerd, and a connoisseur of 90’s cartoons and obscure childhood references. The cat’s out of the bagel now!

July 10, 2024

Telepathy (以心伝心) and Other Coincidences (奇遇)

I was writing to a former intern at Japan Subculture Research Center, Fresca, and asked her to send me her thesis to read—just as she mailed me. I think I was two seconds ahead of her. It was a remarkable coincidence or maybe telepathy. Which got me interested in the many words for the complementary subjects in Japanese. So for your entertainment—here you are.

Telepathy

以心伝心 (いしんでんしん) – Ishin Denshin

Imagine you’re sitting in a crowded Tokyo café, and you suddenly get this eerie feeling that your friend, who’s halfway across the city, really needs to tell you something. No texts, no calls—just a weird vibe. That’s Ishin Denshin, where hearts speak directly to each other, bypassing those pesky cell towers. It’s like when you’re on a date and you just know your partner is thinking about leaving without paying the bill. 食い逃げはダメだ!

心霊交流 (しんれいこうりゅう) – Shinrei KouryuuPicture yourself at a séance, the kind with flickering candles and a medium who’s a bit too enthusiastic. Suddenly, you feel an icy breeze, and it’s not because the AC is cranked up. It’s your grandfather, reaching out to you from the great beyond. He’s got something to say, and of course, it’s, “Why’d you get that godawful tattoo!? What were you thinking? Would you want to wear the same t-shirt every day? But noooo, you get a tattoo! Oy vey!” Shinrei Kouryuu is like that ghostly chat you have without words, where spirits exchange pleasantries—or maybe just complain about the afterlife’s lack of Wi-Fi.

精神感応 (せいしんかんのう) – Seishin Kannou

This one’s for those moments when you feel a twinge of anxiety and then, bam! You find out your boss is going to assign you to write a condom review article. Seishin Kannou is all about that psychic sensitivity, where your mind picks up on vibes faster than a caffeine addict at a coffee convention.

テレパシー – Terepashī

Ah, the good old loanword from English. Terepashī is like wearing a tinfoil hat but actually getting reception. It’s the mind-to-mind communication that you wish you had during those awkward silences at family dinners. Just think of it as the mental equivalent of sliding into someone’s DMs.

Words related to Amazing Coincidence

奇遇 (きぐう) – Kigu

Ever bumped into your high school nemesis at a sumo wrestling match in Osaka? That’s Kigu for you—a strange coincidence that makes you question if the universe is playing a cosmic joke. It’s like finding out your blind date is your dentist’s cousin’s yoga instructor.

偶然の一致 (ぐうぜんのいっち) – Gūzen no Icchi

This phrase is like finding your soulmate who also happens to be allergic to nori and is obsessed with collecting vintage Ghost In the Shell figurines. Gūzen no Icchi is when coincidences line up so perfectly, you start wondering if you’re actually living in a rom-com.

思いがけない偶然 (おもいがけないぐうぜん) – Omoigakenai Gūzen

Imagine you’re walking down the street and a winning lottery tickets lands on your head at the exact moment you decide to quit your job. Omoigakenai Gūzen is that unexpected coincidence that makes you look up and say, “Really, universe? Really?”

巡り合わせ (めぐりあわせ) – Meguriawase

Think of Meguriawase as the universe’s way of setting up a blind date with destiny. It’s those fortunate encounters that make you believe in fate, like running into an old friend at a ramen shop and discovering you both have a newfound love for Ska Paradise Orchestra

So, next time you experience a telepathic moment or a mind-blowing coincidence, remember these Japanese words and enjoy the delightful weirdness of it all—and if you’re a writer be glad you have such a wonderful editor. You should really buy him or her or them a cup of coffee.