Toby Boy's Blog: Prince of Middlemass - Posts Tagged "dark-academia"

Sneak peek at Don’t Scare Me (KOMM Book 2): new art reveal inside!

This is an excerpt from the upcoming book 'Don't Scare Me' (sequel to the break-out thriller, King of Middlemass). Toby Boy subject to change, all rights reserved.

KLONDIKE SWIM

Annette had once craved the intrigue and machinations of a debutante for herself. Yet it was another woman’s wish that the girl should spread her wings and fly. So it was a mean thing, after setting foot upon the road, to feel the constant cold shoulder—like a torrent borne against her. She remembered the woman’s many kindnesses, and even her well-meaning cruelties. These had shaped Annette. She imagined her mother-figure having been treated even more shabbily than she herself, and all over what? Something as coarse as money. It was times like these when Annette remembered revenge. Success would be a fine revenge—the top of the pyramid, the coldest of the cold, the cruelest of the cruel. But revenge was also revenge.

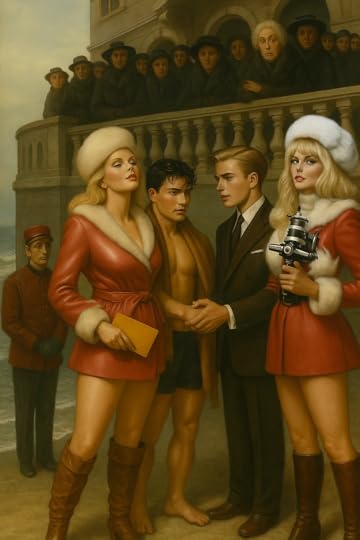

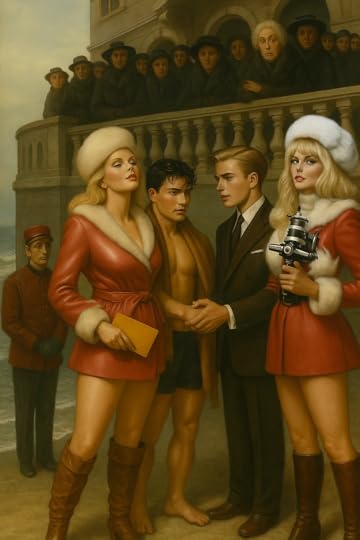

The terrace of the Providence Hotel was a stone bowl overlooking the winter strand, lined with women plucked from colonial portraiture postures rigid, faces painted with certainty, stoles of sable sweeping the flagstones. Their voices were a low hum of judgment, waiting with eyes as sharp as oyster knives.

But Annette’s arrival silenced their hum. Her gaze swept over the terrace, noting the pursed lips and narrowed eyes, before drifting to the sea-dark strand below. There he was. Next, she selected her steps—toe-heel, toe-heel—passing the brazier fires and wine-glass stares with the breezy disinterest perfected only by someone who knew precisely how much she was being watched. She stopped at the terrace’s lip. above the hotel’s east-facing foundation where gigantic castle stone met the winter mud and the mud met the sea.

She leaned scandalously over the stone fence. “Ooo,” she crooned, loud enough for anyone. “That one’s my one. Riv! Make a muscle, honey.” Below, in the bitter wind of the icy swim, Rivers stood among the pale and the persecuted—retiree torsos drawn like uncooked poultry. But Rivers, resplendent in the Riviera swimwear Annette had chosen (to break hearts, not records,) needed only to flex. His bicep wound itself up like an invitation. Light caught on his shoulder and etched geometry into his skin.

There was no mistaking whom she had meant. But even if she hadn’t said it, one would have known.

She wore a white arctic minx hat, decadent and high-crowned, like a pale blaze of cloud atop her head. Below it, a bombastic jacket in crushed rose hovered above the thigh as if cut by a seamstress with an old grudge against mortal men. Then bare, gleaming skin for winter, followed by deerskin boots, the rich color of heartwood, laced up the calves with something more than functionality in mind.

She placed a hand on her hip with the casual nonchalance of a sculptor claiming credit for a marble Adonis.

A few older matrons instinctively recoiled. One or two held their breath in genuine awe. But a chorus of mumbled disapproval rose, a venomous discord straight out of a Greek tragedy, if the chorus were harpies with powdered faces and pearl chokers.

“That’s vulgar,” hissed one, her tone low but slicing.

“She’s not even registered,” said another, her voice a scalpel cutting through the murmurs with practiced disdain.

“Those hunting leathers are not… APPropriate” murmured a third, failing to find a word that could contain Annette’s audacity.

And from the back, a voice sharp with memory: “It’s her mother all over again.”

The outrage was palpable, a current of resentment pulsing through the terrace like a storm over the sea. Annette had composed the moment deliberately, staged it with the precision of a playwright, and now it gleamed, ready to be sealed in the lacquer of her memory, forever.

It would have remained a fleeting scandal—quickly forgotten—except that the doors to the veranda groaned open again and the rumored pair arrived, trailing a social apocalypse in their wake.

Maddie and Boone stepped onto the terrace like forked thunderbolts. Maddie, her white-blonde curl pinned in an elegant chignon, wore her own crushed-rose jacket and deerskin boots, her obvious poise a ready rebuke to anyone who might stand in her way. Boone, properly groomed and statesmanlike, carried the quiet authority of his ancestry. The matrons’ gazes flickered between Annette’s brazen display and the new arrivals, their disapproval fermenting into something ugly, something that clawed at the edges of decorum itself.

Annette’s upper lip curved into a faint smile.

Rivers had placed fourth, narrowly beaten by a grandfather from the Baltic provinces whose mechanical stroke defied both age and science. By the time Rivers emerged from the surf, slow currents of white steam wisping from his shoulders, Annette was already there, hugging a towel around him like a coronation. Boone, with the polish of a burgeoning statesman, landed a boot on the stamped muddy sand. He extended a hand. "Well swum, Rivers," he said, his voice carrying that timbre, genuine in its admiration yet laced with the awareness of a wider audience. Maddie, her camera out, raised it with a quick, practiced motion and clicked—not posed, not framed, just so. The shutter's snap cut through the wind, capturing the moment: Rivers' damp hair plastered to his forehead, Annette's arm draped over his shoulder, Boone's handshake firm and fraternal. In that instant, amid the congratulations-

"Impressive endurance," Boone added;

"You looked like Poseidon out there," Maddie teased with a slow-blink.

And so, the day’s true victory was etched in the camaraderie of their little gang against the impending chill.

From up on the terrace, among the goings-on, a gray-haired woman in a fox pelt collar leaned over the stony edge. Her voice drifted down like ash. “Such a spectacle,” she said, addressing Boone alone. “But visiting hours at Providence are well over. Those not enrolled ought to be gathering themselves up.”

Annette didn’t flinch. Rivers, the surf and wind still in his ears, did not catch the insult directly, but he clocked its aim and he felt the young woman against him.

“It’s always been the policy,” another called down—a raspy man with only his forehead and eyes visible above the balustrade. “Those without membership privileges always vacate after scheduled events.”

It was true enough. The Hotel Providence was not a hotel in the common sense. It was a private club. One could not simply walk in. One had to be on the list—a list as mysterious as everything else in Roanoke. Its members paid their quarterly dues whether they stayed or not. The rooms never crowded, the staff never hurried, and their silence was as dependable as a wine cellar.

And then: the page-boy. A slight figure in brassy shoes, he picked his way across the muddy strand clutching an envelope as if it were radioactive. He bowed deeply before Annette. “For Miss Annette,” he murmured.

She took it and cracked the seal, her eyes scanning the parchment. “I think it’s an invitation,” she whispered, pulling Rivers close.

Boone cleared his throat the way men do when they’ve decided not to interrupt, and then interrupted. “Just a moment, if you please,” he called, too formal to fight and too vague to obey.

Above, the matrons bristled. Below, Annette refused to yield.

The murmurs swelled again. “The policy stands,” snapped the fox-pelted woman. “Non-members must depart—now.”

Boone looked to Rivers for an out. Rivers only shrugged. “We think it’s an invitation.”

Maddie sidled in on Annette’s other side. “What is it, sweetheart?”

Annette’s eyes widened. “Oh, Riv! I think this must be from Bee. You see? Beatrice Francesca.”

Rivers could not remember who Beatrice Francesca was. But he recognized a coup when he saw one.

The terrace tribunals simmered. “We really would prefer not to call the usher,” said the fox-pelted woman, in a tone suggesting she very much hoped that someone else would.

“It sets the wrong precedent,” muttered the papery man.

Maddie stepped forward, plucked the envelope, and scanned it. “Oh. Darling, it’s gold.” She handed it back like a birthright. “It’s a gold invitation, Annette. It’s the kind they send when they want everyone to see who got it.”

The terrace hushed.

Still, the page-boy lingered.

Spotting him, Annette added, “Accommodation is now… how you say—expected and required.”

Rivers gestured at his Italian swim trunks. “These don’t really have pockets,” he explained. “Design-wise.”

Miss Maddie shrugged. Boone was only too happy to intervene. To grasp hands.

Annette held the envelope aloft. “Upstairs,” she announced for all the bastards in all the cheap seats to hear, “I’ve been invited upstairs.”

Upstairs

The penthouse suite of the Providence Hotel was an empty cathedral—an interior of impossible scale and solemnity. The ceiling rose in a black dome ribbed with ironwork, more like an observatory turned inward than anything meant for hospitality. The marble floor gleamed under the flickering firelight, save for a single, unrolled Persian carpet—worn thin at its center—upon which stood a tall, high-backed chair of carved elm, tufted in oxblood velvet. A wide, open-mouthed hearth dominated the far wall, its brick maw lined with wrought-iron spikes that jutted upward like broken teeth. From within, a fire cracked and danced, casting spasms of orange light across the domed ceiling as if to animate the room in breathing shadows.

In the chair sat a diminutive girl—no more than fifteen by appearance, though her posture made her older. Blonde ringlets fell perfectly down the sides of her face, unmussed and deliberate, framing a countenance that seemed both childlike and etched. She was dressed as if for a holiday excursion in another century: a gray traveling coat cut short to accommodate lace cuffs, black stockings, and a miniature top hat fixed with ribbon beneath her chin, the kind of affectation one might see in a painting, or an inherited photograph no one ever explains. She balanced on her knees a leather-bound tome the size of a butcher’s ledger.

Somewhere a door opened with a hush and a click. “Hello?” called Annette, her voice softened by the enormous silence. The door closed again with a finality not unlike the turning of a self-locking vault.

Annette’s heeled boots tapped across the marble—steady, echoing, assured. She paced forward from the edge of the antechamber’s gloom, stepping out from behind the silhouette like an ingenue whose arrival had been much ballyhooed and tantalized over. A sliver of ashen light seeped in through a bay window, where the low winter sky pressed its remaining light against the glass in a kind of permanent winter dusk. Her white-blonde bob was unshadowed now—her extravagant hat having been removed somewhere below—and her crushed-rose jacket had been left open, revealing the pristine white of her blouse and skirt beneath. Her figure, tall, deliberate, and no longer careless was cut stark against the room’s aged grandeur.

“Bee!” she exclaimed with that old recognition as her eyes lit upon the girl in the chair.

At this, the girl snapped shut the book with both hands, the sound heavy and blunt like a closing doctrine. She slid the tome to one side and stood, though she barely reached Annette’s shoulder. Her face was pale, round, and slightly hollowed beneath the cheekbones. Whatever warmth had once lived there had been replaced by a kind of studied politeness. Annette moved in for a hug, arms outstretched with schoolgirl fondness, but the girl intercepted her with a two-handed clasp instead—both of Annette’s hands now held in both of hers, as if initiating a solemn pact.

“Beatrice Francesca,” said Annette, smiling with effort, “you look just the same as ever. Exactly the same.”

And it was true. Beatrice looked untouched by time. Not ageless—there was something too knowing in the gaze—but rather perfectly preserved, like a figure trapped in amber. Beatrice looked up at her, the way one might look up at a taller, luckier cousin. Her mouth twitched, not quite with envy, but with something adjacent. “And you, Annette,” she said, her voice sugar-dipped and very dry at the same time. “Aren’t you womanly though?”

Annette, who knew how to navigate compliments that carried knives, answered with a gentle murmur and a tilted head, smoothing the air like a ribbon drawing taut. “Your invitation came at a welcome time,” she said, letting warmth do the work of distraction. “Why did you want to see me, old girl?”

Still holding her hands, Beatrice gave a slight tremble. Her voice rose theatrically, pitched toward unseen balconies.

“Oh, Miss Annette,” she cried. “You must never forgive me. No matter what I say, you simply mustn’t.”

Annette matched the energy with dutiful sisterliness, tilting her chin and drawing a commensurate frown. “Well of course I forgive you, dear,” she said. “Now tell big sister what it’s all about.”

At that, Beatrice released her hands, turned her back, and took a few steps toward the fireplace. The firelight clung to her figure in a way that made her seem almost translucent, like a glass candle-holder. She placed her hands behind her back, composed herself, then turned again, her expression fixed. “I might as well tell you,” she said. “I already had a clatch of constables up here. Before you.”

Annette blinked.

“They came because I sent for them in a private dispatch,” Beatrice continued. “But when they heard my request, they soon discovered reasons to be elsewhere. They were my last chance, or so I thought. And then—just as I stepped onto the terrace for air—I looked down…” She paused, letting her eyes settle on the bay window as if seeing it all again. “There you were. Toweling off your hunky Mister Rivers.” She said it like a name she’d read but never spoken aloud. “And then I remembered. You both were the most recent Queen and King of Festival, is it not so?”

“Well, yes,” said Annette, suddenly remembering the consequences of Festival weekend. There had been danger, there was a fire, there was the small matter of stolen purses and commensurate documents. Annette checked her breathing and muted her expression. “But why should that matter?”

Beatrice smiled. This time it reached both of her eyes. “Because, Miss Annette,” she said, her voice soft now, almost reverent, “I am now the mistress of Solstice Court.”

Beatrice Francesca moved slowly toward the hearth again, as if the fire might illuminate her plea. The light cast up the side of her face in streaks, her childish features mottled by adult unease. She did not return to the high-back chair. She placed one gloved hand on a wrought-iron poker, leaning onto it with the tiredness of someone who had not slept.

“Miss Annette,” she said, drawing out the syllables, “do you want to hear something curious?”

Annette inclined her head. She had learned that strange girls often had strange things to say, and that most of it could be survived with charm.

Beatrice didn’t meet her eyes. She reached into a slim rectangular pocket and withdrew a small scroll bound with a lavender ribbon, slightly frayed. She thumbed her thumb against it. “A list of names was given to me,” Beatrice went on, “the lawyers compiled it. They told me to choose who I wanted, as if I would know.”

Annette raised an eyebrow.

Beatrice looked up now, eyes bright with that same theatricality from before, though now it glinted like desperation.

“One of the names was Mister Rivers. Only, he was listed as... ‘The Kid Constable.’”

Annette blinked. Her mouth parted slightly, “He does not care much for that title anymore,” she said.

“No,” Beatrice agreed. “But it’s a part of his record now. Names don’t vanish just because you want them to.” She let that hang a moment, then abruptly dropped the scroll into the fire. Her posture shifted. Her voice grew quicker. “Everything changed once they named me inheritor,” she said. “At first it was easy, telegrams or boring old letters from lawyers. But not even a week after the announcement, things began to go wrong.”

Annette deduced that this was no time to interrupt, ‘Bee’ was on a tear.

“Milk turned to cheese overnight,” Beatrice said. “I don’t mean spoiled, I mean... fully congealed. Bottles in the pantry never even opened.” She held up a finger, counting off. “Backwards writing appeared on mirrors and windows. Not once. Dozens of times. And someone stuffed the chimneys,” Beatrice added. “All of them. With acorns. Hundreds of them. When the fire was lit, it rained smoke and nutmeat and this bitter, bitter stench.”

That one caught Annette. “Acorns.” She pressed a finger to her lips. This encounter had ceased to be charming.

“When that didn't drive me out, the real dangers began. Doors that shouldn't be opened... fires that start by themselves. I’m not afraid for myself, of course,” Beatrice continued, stepping forward again. “But for the innocent people. And I have only mentioned the physical signs. There is more at work. There is always more.” She paused. Then, with exquisite slowness, she removed a single gold pin from the lapel of her coat—an enameled key, small but intricately worked—and held it out, flat in her palm. “I want to make an official request,” she said. “In the name of peace and tradition. Miss Annette. Mister Rivers. My Queen. My King. I would like you to track down the source of these disturbances. Identify it. Capture it, if you can. No, you must.”

Annette did not move to take the pin-key. She was watching Bee’s face now with studied precision.

Beatrice smiled faintly, as if that scrutiny were expected. “I will sponsor you both. Of course. You’ll be enrolled—formally—into the Providence Hotel. Membership. Keys. Quarters, if you like them. And you will be welcome guests at Solstice Court. Not as socialites. Not as spectators. As protectors. Just as it was done a century ago.”

Annette stepped slowly toward the fireplace. She stared at the flames, watching them fracture against the iron teeth of the hearth. She didn’t answer immediately. "I’ll need to smoke on it, dear," she said. But her eyes never lifted from the flames, where all the while the edges of the lavender-bound scroll blackened and curled and burned.

KLONDIKE SWIM

Annette had once craved the intrigue and machinations of a debutante for herself. Yet it was another woman’s wish that the girl should spread her wings and fly. So it was a mean thing, after setting foot upon the road, to feel the constant cold shoulder—like a torrent borne against her. She remembered the woman’s many kindnesses, and even her well-meaning cruelties. These had shaped Annette. She imagined her mother-figure having been treated even more shabbily than she herself, and all over what? Something as coarse as money. It was times like these when Annette remembered revenge. Success would be a fine revenge—the top of the pyramid, the coldest of the cold, the cruelest of the cruel. But revenge was also revenge.

The terrace of the Providence Hotel was a stone bowl overlooking the winter strand, lined with women plucked from colonial portraiture postures rigid, faces painted with certainty, stoles of sable sweeping the flagstones. Their voices were a low hum of judgment, waiting with eyes as sharp as oyster knives.

But Annette’s arrival silenced their hum. Her gaze swept over the terrace, noting the pursed lips and narrowed eyes, before drifting to the sea-dark strand below. There he was. Next, she selected her steps—toe-heel, toe-heel—passing the brazier fires and wine-glass stares with the breezy disinterest perfected only by someone who knew precisely how much she was being watched. She stopped at the terrace’s lip. above the hotel’s east-facing foundation where gigantic castle stone met the winter mud and the mud met the sea.

She leaned scandalously over the stone fence. “Ooo,” she crooned, loud enough for anyone. “That one’s my one. Riv! Make a muscle, honey.” Below, in the bitter wind of the icy swim, Rivers stood among the pale and the persecuted—retiree torsos drawn like uncooked poultry. But Rivers, resplendent in the Riviera swimwear Annette had chosen (to break hearts, not records,) needed only to flex. His bicep wound itself up like an invitation. Light caught on his shoulder and etched geometry into his skin.

There was no mistaking whom she had meant. But even if she hadn’t said it, one would have known.

She wore a white arctic minx hat, decadent and high-crowned, like a pale blaze of cloud atop her head. Below it, a bombastic jacket in crushed rose hovered above the thigh as if cut by a seamstress with an old grudge against mortal men. Then bare, gleaming skin for winter, followed by deerskin boots, the rich color of heartwood, laced up the calves with something more than functionality in mind.

She placed a hand on her hip with the casual nonchalance of a sculptor claiming credit for a marble Adonis.

A few older matrons instinctively recoiled. One or two held their breath in genuine awe. But a chorus of mumbled disapproval rose, a venomous discord straight out of a Greek tragedy, if the chorus were harpies with powdered faces and pearl chokers.

“That’s vulgar,” hissed one, her tone low but slicing.

“She’s not even registered,” said another, her voice a scalpel cutting through the murmurs with practiced disdain.

“Those hunting leathers are not… APPropriate” murmured a third, failing to find a word that could contain Annette’s audacity.

And from the back, a voice sharp with memory: “It’s her mother all over again.”

The outrage was palpable, a current of resentment pulsing through the terrace like a storm over the sea. Annette had composed the moment deliberately, staged it with the precision of a playwright, and now it gleamed, ready to be sealed in the lacquer of her memory, forever.

It would have remained a fleeting scandal—quickly forgotten—except that the doors to the veranda groaned open again and the rumored pair arrived, trailing a social apocalypse in their wake.

Maddie and Boone stepped onto the terrace like forked thunderbolts. Maddie, her white-blonde curl pinned in an elegant chignon, wore her own crushed-rose jacket and deerskin boots, her obvious poise a ready rebuke to anyone who might stand in her way. Boone, properly groomed and statesmanlike, carried the quiet authority of his ancestry. The matrons’ gazes flickered between Annette’s brazen display and the new arrivals, their disapproval fermenting into something ugly, something that clawed at the edges of decorum itself.

Annette’s upper lip curved into a faint smile.

Rivers had placed fourth, narrowly beaten by a grandfather from the Baltic provinces whose mechanical stroke defied both age and science. By the time Rivers emerged from the surf, slow currents of white steam wisping from his shoulders, Annette was already there, hugging a towel around him like a coronation. Boone, with the polish of a burgeoning statesman, landed a boot on the stamped muddy sand. He extended a hand. "Well swum, Rivers," he said, his voice carrying that timbre, genuine in its admiration yet laced with the awareness of a wider audience. Maddie, her camera out, raised it with a quick, practiced motion and clicked—not posed, not framed, just so. The shutter's snap cut through the wind, capturing the moment: Rivers' damp hair plastered to his forehead, Annette's arm draped over his shoulder, Boone's handshake firm and fraternal. In that instant, amid the congratulations-

"Impressive endurance," Boone added;

"You looked like Poseidon out there," Maddie teased with a slow-blink.

And so, the day’s true victory was etched in the camaraderie of their little gang against the impending chill.

From up on the terrace, among the goings-on, a gray-haired woman in a fox pelt collar leaned over the stony edge. Her voice drifted down like ash. “Such a spectacle,” she said, addressing Boone alone. “But visiting hours at Providence are well over. Those not enrolled ought to be gathering themselves up.”

Annette didn’t flinch. Rivers, the surf and wind still in his ears, did not catch the insult directly, but he clocked its aim and he felt the young woman against him.

“It’s always been the policy,” another called down—a raspy man with only his forehead and eyes visible above the balustrade. “Those without membership privileges always vacate after scheduled events.”

It was true enough. The Hotel Providence was not a hotel in the common sense. It was a private club. One could not simply walk in. One had to be on the list—a list as mysterious as everything else in Roanoke. Its members paid their quarterly dues whether they stayed or not. The rooms never crowded, the staff never hurried, and their silence was as dependable as a wine cellar.

And then: the page-boy. A slight figure in brassy shoes, he picked his way across the muddy strand clutching an envelope as if it were radioactive. He bowed deeply before Annette. “For Miss Annette,” he murmured.

She took it and cracked the seal, her eyes scanning the parchment. “I think it’s an invitation,” she whispered, pulling Rivers close.

Boone cleared his throat the way men do when they’ve decided not to interrupt, and then interrupted. “Just a moment, if you please,” he called, too formal to fight and too vague to obey.

Above, the matrons bristled. Below, Annette refused to yield.

The murmurs swelled again. “The policy stands,” snapped the fox-pelted woman. “Non-members must depart—now.”

Boone looked to Rivers for an out. Rivers only shrugged. “We think it’s an invitation.”

Maddie sidled in on Annette’s other side. “What is it, sweetheart?”

Annette’s eyes widened. “Oh, Riv! I think this must be from Bee. You see? Beatrice Francesca.”

Rivers could not remember who Beatrice Francesca was. But he recognized a coup when he saw one.

The terrace tribunals simmered. “We really would prefer not to call the usher,” said the fox-pelted woman, in a tone suggesting she very much hoped that someone else would.

“It sets the wrong precedent,” muttered the papery man.

Maddie stepped forward, plucked the envelope, and scanned it. “Oh. Darling, it’s gold.” She handed it back like a birthright. “It’s a gold invitation, Annette. It’s the kind they send when they want everyone to see who got it.”

The terrace hushed.

Still, the page-boy lingered.

Spotting him, Annette added, “Accommodation is now… how you say—expected and required.”

Rivers gestured at his Italian swim trunks. “These don’t really have pockets,” he explained. “Design-wise.”

Miss Maddie shrugged. Boone was only too happy to intervene. To grasp hands.

Annette held the envelope aloft. “Upstairs,” she announced for all the bastards in all the cheap seats to hear, “I’ve been invited upstairs.”

Upstairs

The penthouse suite of the Providence Hotel was an empty cathedral—an interior of impossible scale and solemnity. The ceiling rose in a black dome ribbed with ironwork, more like an observatory turned inward than anything meant for hospitality. The marble floor gleamed under the flickering firelight, save for a single, unrolled Persian carpet—worn thin at its center—upon which stood a tall, high-backed chair of carved elm, tufted in oxblood velvet. A wide, open-mouthed hearth dominated the far wall, its brick maw lined with wrought-iron spikes that jutted upward like broken teeth. From within, a fire cracked and danced, casting spasms of orange light across the domed ceiling as if to animate the room in breathing shadows.

In the chair sat a diminutive girl—no more than fifteen by appearance, though her posture made her older. Blonde ringlets fell perfectly down the sides of her face, unmussed and deliberate, framing a countenance that seemed both childlike and etched. She was dressed as if for a holiday excursion in another century: a gray traveling coat cut short to accommodate lace cuffs, black stockings, and a miniature top hat fixed with ribbon beneath her chin, the kind of affectation one might see in a painting, or an inherited photograph no one ever explains. She balanced on her knees a leather-bound tome the size of a butcher’s ledger.

Somewhere a door opened with a hush and a click. “Hello?” called Annette, her voice softened by the enormous silence. The door closed again with a finality not unlike the turning of a self-locking vault.

Annette’s heeled boots tapped across the marble—steady, echoing, assured. She paced forward from the edge of the antechamber’s gloom, stepping out from behind the silhouette like an ingenue whose arrival had been much ballyhooed and tantalized over. A sliver of ashen light seeped in through a bay window, where the low winter sky pressed its remaining light against the glass in a kind of permanent winter dusk. Her white-blonde bob was unshadowed now—her extravagant hat having been removed somewhere below—and her crushed-rose jacket had been left open, revealing the pristine white of her blouse and skirt beneath. Her figure, tall, deliberate, and no longer careless was cut stark against the room’s aged grandeur.

“Bee!” she exclaimed with that old recognition as her eyes lit upon the girl in the chair.

At this, the girl snapped shut the book with both hands, the sound heavy and blunt like a closing doctrine. She slid the tome to one side and stood, though she barely reached Annette’s shoulder. Her face was pale, round, and slightly hollowed beneath the cheekbones. Whatever warmth had once lived there had been replaced by a kind of studied politeness. Annette moved in for a hug, arms outstretched with schoolgirl fondness, but the girl intercepted her with a two-handed clasp instead—both of Annette’s hands now held in both of hers, as if initiating a solemn pact.

“Beatrice Francesca,” said Annette, smiling with effort, “you look just the same as ever. Exactly the same.”

And it was true. Beatrice looked untouched by time. Not ageless—there was something too knowing in the gaze—but rather perfectly preserved, like a figure trapped in amber. Beatrice looked up at her, the way one might look up at a taller, luckier cousin. Her mouth twitched, not quite with envy, but with something adjacent. “And you, Annette,” she said, her voice sugar-dipped and very dry at the same time. “Aren’t you womanly though?”

Annette, who knew how to navigate compliments that carried knives, answered with a gentle murmur and a tilted head, smoothing the air like a ribbon drawing taut. “Your invitation came at a welcome time,” she said, letting warmth do the work of distraction. “Why did you want to see me, old girl?”

Still holding her hands, Beatrice gave a slight tremble. Her voice rose theatrically, pitched toward unseen balconies.

“Oh, Miss Annette,” she cried. “You must never forgive me. No matter what I say, you simply mustn’t.”

Annette matched the energy with dutiful sisterliness, tilting her chin and drawing a commensurate frown. “Well of course I forgive you, dear,” she said. “Now tell big sister what it’s all about.”

At that, Beatrice released her hands, turned her back, and took a few steps toward the fireplace. The firelight clung to her figure in a way that made her seem almost translucent, like a glass candle-holder. She placed her hands behind her back, composed herself, then turned again, her expression fixed. “I might as well tell you,” she said. “I already had a clatch of constables up here. Before you.”

Annette blinked.

“They came because I sent for them in a private dispatch,” Beatrice continued. “But when they heard my request, they soon discovered reasons to be elsewhere. They were my last chance, or so I thought. And then—just as I stepped onto the terrace for air—I looked down…” She paused, letting her eyes settle on the bay window as if seeing it all again. “There you were. Toweling off your hunky Mister Rivers.” She said it like a name she’d read but never spoken aloud. “And then I remembered. You both were the most recent Queen and King of Festival, is it not so?”

“Well, yes,” said Annette, suddenly remembering the consequences of Festival weekend. There had been danger, there was a fire, there was the small matter of stolen purses and commensurate documents. Annette checked her breathing and muted her expression. “But why should that matter?”

Beatrice smiled. This time it reached both of her eyes. “Because, Miss Annette,” she said, her voice soft now, almost reverent, “I am now the mistress of Solstice Court.”

Beatrice Francesca moved slowly toward the hearth again, as if the fire might illuminate her plea. The light cast up the side of her face in streaks, her childish features mottled by adult unease. She did not return to the high-back chair. She placed one gloved hand on a wrought-iron poker, leaning onto it with the tiredness of someone who had not slept.

“Miss Annette,” she said, drawing out the syllables, “do you want to hear something curious?”

Annette inclined her head. She had learned that strange girls often had strange things to say, and that most of it could be survived with charm.

Beatrice didn’t meet her eyes. She reached into a slim rectangular pocket and withdrew a small scroll bound with a lavender ribbon, slightly frayed. She thumbed her thumb against it. “A list of names was given to me,” Beatrice went on, “the lawyers compiled it. They told me to choose who I wanted, as if I would know.”

Annette raised an eyebrow.

Beatrice looked up now, eyes bright with that same theatricality from before, though now it glinted like desperation.

“One of the names was Mister Rivers. Only, he was listed as... ‘The Kid Constable.’”

Annette blinked. Her mouth parted slightly, “He does not care much for that title anymore,” she said.

“No,” Beatrice agreed. “But it’s a part of his record now. Names don’t vanish just because you want them to.” She let that hang a moment, then abruptly dropped the scroll into the fire. Her posture shifted. Her voice grew quicker. “Everything changed once they named me inheritor,” she said. “At first it was easy, telegrams or boring old letters from lawyers. But not even a week after the announcement, things began to go wrong.”

Annette deduced that this was no time to interrupt, ‘Bee’ was on a tear.

“Milk turned to cheese overnight,” Beatrice said. “I don’t mean spoiled, I mean... fully congealed. Bottles in the pantry never even opened.” She held up a finger, counting off. “Backwards writing appeared on mirrors and windows. Not once. Dozens of times. And someone stuffed the chimneys,” Beatrice added. “All of them. With acorns. Hundreds of them. When the fire was lit, it rained smoke and nutmeat and this bitter, bitter stench.”

That one caught Annette. “Acorns.” She pressed a finger to her lips. This encounter had ceased to be charming.

“When that didn't drive me out, the real dangers began. Doors that shouldn't be opened... fires that start by themselves. I’m not afraid for myself, of course,” Beatrice continued, stepping forward again. “But for the innocent people. And I have only mentioned the physical signs. There is more at work. There is always more.” She paused. Then, with exquisite slowness, she removed a single gold pin from the lapel of her coat—an enameled key, small but intricately worked—and held it out, flat in her palm. “I want to make an official request,” she said. “In the name of peace and tradition. Miss Annette. Mister Rivers. My Queen. My King. I would like you to track down the source of these disturbances. Identify it. Capture it, if you can. No, you must.”

Annette did not move to take the pin-key. She was watching Bee’s face now with studied precision.

Beatrice smiled faintly, as if that scrutiny were expected. “I will sponsor you both. Of course. You’ll be enrolled—formally—into the Providence Hotel. Membership. Keys. Quarters, if you like them. And you will be welcome guests at Solstice Court. Not as socialites. Not as spectators. As protectors. Just as it was done a century ago.”

Annette stepped slowly toward the fireplace. She stared at the flames, watching them fracture against the iron teeth of the hearth. She didn’t answer immediately. "I’ll need to smoke on it, dear," she said. But her eyes never lifted from the flames, where all the while the edges of the lavender-bound scroll blackened and curled and burned.

Published on August 25, 2025 17:42

•

Tags:

2025, dark-academia, new-series, ongoing-series, thriller

Prince of Middlemass

short, stand-alone adventures which include the same world, characters, and themes as the novel "king of middlemass"

short, stand-alone adventures which include the same world, characters, and themes as the novel "king of middlemass"

...more

- Toby Boy's profile

- 14 followers