Eric Schliesser's Blog, page 5

March 19, 2023

On Newton's Refutation of the Mechanical Philosophy

In the recent philosophical reception of Newton there is an understandable tendency to focus on the inverse square law of universal gravitation. I don't mean to suggest this is the only such focus; arguably his views on Space have shaped -- through the good works of Stein and Earman -- also debates over spacetime theories.

The effect of this telescoping has also impacted, I think, the way in which the debate between the mechanical and Newtonian philosophy has been understood. The former is said to posit a contact model in which contact between very small corpuscles explains a lot of observed phenomena. A typical mechanical philosopher creates a hypothetical model, a machine with pulleys and levers (etc.), that can make observed phenomena intelligible. In the mechanical philosophy, which itself was directed against a variety of Aristotelian and Scholastic projects, efficient causation -- once one of four canonical causes (including formal, final, and material) -- has achieved a privileged status.

The scholarly fascination with the status of action at a distance is, thus, readily explicable because it violates the very model of intelligibility taken for granted in the mechanical philosophy. As Newton notes in the General Scholium (first published in the 1713 second edition of the Principia), universal gravity "operates, not according to the quantity of the surfaces of the particles upon which it acts, (as mechanical causes use to do,) but according to the quantity of the solid matter which they contain, and propagates its virtue on all sides, to immense distances, decreasing always in the duplicate proportion of the distances."

Before I get to the main point of today's post, I offer two asides. First, with its emphasis on hypothetical explanations, the mechanical philosophers (and here I use the term to cover people as diverse as Beeckman, Descartes, Boyle, and Huygens) also exhibit a deep strain of skepticism about the very possibility of truly grasping nature's innards as it were. Spinoza's natura naturans and even Kant's ding-an-sich are the enduring expressions of this strain of skepticism (allowing that Kant is much less a mechanical philosopher). To put this as a serious joke: the PSR is, thus, not an act of intellectual hubris, but a self-limitation of the knower when it comes to fundamental ontology. Second, by showing that there is something wholly unintelligible about the way motion is supposed to be transferred from one body to the other (Essay 2.23.28), Locke, who gets so little credit among contemporary philosophers, had already imploded the pretensions of the mechanical philosophy on conceptual grounds. Okay, so much for set up.

The mechanical philosophers were not so na��ve to think that models that relied on mere impulse, matter in motion, could create hypothetical models of sufficient complexity to provide hypothetical explanations of the phenomena. This is especially a problem because the mechanical philosophers posited a homogeneous matter. So that in addition to matter and motion, they posited size and shape not merely as effects of motion, but also as key explanatory factors in the hypothetical models of visible phenomena (this can be seen in Descartes, Gassendi, and Boyle, whose "The Origin of Forms and Qualities according to the Corpuscular Philosophy" (1666), I take as a canonical statement of the mechanical philosophy). So that the mechanical philosophy is committed to privileging (to echo a felicitous phrase by Biener and Smeenk [here; and here]) geometric features of bodies.

Even leaving aside the inverse square law and its universal scope, Newton's experimental work on gravity demolished a key feature of the mechanical philosophy: size and shape are irrelevant to understand gravity. I quote from Henry Pemberton's View of Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophy (1728):

Pemberton (who was the editor of the third, 1726 edition of the Principia) goes on to give Boyle's famous vacuum experiments with falling feathers and stones as evidence for this argument. That is, Pemberton uses Boyle's experimental work to refute Boyle's mechanical philosophy.

Now, in the Principia, references to Boyle's experiment got added only to the (1713) second edition in two highly prominent places: Cotes added a reference to it in his editor's introduction and Newton added a reference to it in the General Scholium at the end of the book. In both cases Boyle's experiment is used as a kind of illustration for the claim that without air resistance falling bodies are equally accelerated and for the plausibility of positing an interstellar vacuum. That is, if one reads the Principia superficially (by looking at prominent material at the front and end), it seems as if Newton and Boyle have converging natural philosophies.

Of course, neither Pemberton nor Newton rely exclusively on Boyle's vacuum experiment to make the point that shape and size (or geometry) is not a significant causal factor when it comes to gravity. The key work is done by pendulum experiments with different metals. (These can be found in Book II of the Principia, which is often skipped, although he drives the point home in Book III, Prop. 6 of Principia.) These show that quantity of matter is more fundamental than shape. And, crucially, shape & size and quantity of matter need not be proportional to or proxies of each other. This fact was by no means obvious, and at the start of the Principia. even Newton offers, as Biener and Smeenk have highlighted, a kind of geometric conception of quantity of matter in his first definition before suggesting that 'quantity of matter' is proportional to weight (and indicating his pendulum experiments as evidence thereof).

Let me wrap up. What's important here is that even if Newton had been wrong about the universal nature of the inverse square law, he showed that the mechanical philosophy cannot account for the experimentally demonstrated features of terrestrial (and planetary) gravity. (So, that the mechanical philosophy is not a natural way to understand Galilean fall.) And this means that in addition to Locke's conceptual claim, Newton shows that the mechanical philosophy's emphasis on just one kind of efficient causation, by way of contact, is not sufficient to explain the system of nature.

What I say here is not surprising to students of Newton. But it's also not really much emphasized. To be sure, Newton, too, accepted a kind of homogeneous matter, but rather than its size and figure, he showed that an abstract quantity (mass) is more salient. Of course, how to understand mass in Newton's philosophy opens new questions, for as Ori Belkind has argued it should not be taken as a property of matter, but rather as a measure.

March 12, 2023

Mostly good news: Covid Diaries

It's been about ten weeks since I last wrote an entry in my covid diary. (For my official "covid diaries" see here; here; here; here;here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; here; and here.) That's the longest interval since I first start them. This is primarily due to the fact that there is not much new to report, and that's good news.

When I plan my days carefully with breaks between socializing, go to bed early, and take my anti-inflammatories as needed, I have a very decent quality of life. I can hang out in public even in contexts that were cognitively quite challenging about half a year ago. I have been teaching my giant introductory lecture course (with 561 registered students) with little fallout. After lecture, I still have trouble turning my brain off, and sleeping normally (I have had a few midnight headaches), but by mid-morning the following day I tend to be normal again. In general, I still need more melatonin than I would like to asleep through the night. (I have no trouble falling asleep since to my sister's meditation techniques. But I often wake up a lot during the night.)

This past week, I was in Singapore (don't cry for me), and while the jet-lag and excitement impacted me, I was socially 'on' for most of the time without any noticeable effects. So, while I still often find that after two hours of socializing in public I need some rest, this is by no means always so.

Most of my long covid limitations are invisible to outsiders now. However, I am still terrible at cognitive multi-tasking (e.g., I can't really eavesdrop), and I am pretty sure my memory capacity for names has deteriorated. More subtly, I find it difficult to read heavy duty metaphysics (I catch myself skipping sentences) or certain kind of 'serious' novels (get bored easily). I also notice that I need to check the grammar more regularly in my writing (and that I often write words that sound like the word I originally intended). But I have become much more disciplined about avoiding cluttering my schedule and about not multi-tasking in the moment or even, more abstractly, the same period. So, for example, in periods when I teach I try not to fuss over research. Consequently, I am much more present when I do things (and so skilled at them).

So, all in all, I am fairly optimistic that things are heading in the right direction. It's so unexpected that I still find myself feeling that each day is a bonus day. As a consequence, and a few years of forced reflecting on my life, I am also much more at ease with letting go of things I was once very ambitious to acquire. It's probably a sign of middle-age, too. But that kind of glass is half full 'normality' is quite fine.

March 7, 2023

On Kukathas' Liberalism and elite (capture) Theory

This is not because the characterization of political society Walzer offers is untrue to reality. Political society is a substantive community, for there is no such thing as a purely procedural association. And associations with long histories will invariably develop substantial norms, and acquire deep allegiances. And yet, this is not so different from international society and, more particularly, that form of international society that is an empire. Thirty years ago every Australian school child recognized Empire Day, and Australians generally celebrated their membership of the former British Empire. Today, almost all school children are entirely unaware it ever existed. The polity whose history is taught has been contracted in size, and the story itself is being retold to place it more securely in the Asia-Pacific region and to sever the ties with Europe. But this is nothing new. Very few countries were never parts of empires; and some have grown so large as to subsume the parts the empire occupied. In many of these political societies the polity is the product of domination rather than the construction of the people. Political societies are built by elites, often against the wishes of many.

Of course, smaller political orders���whether small empires or larger states���are more likely to develop distinctive and substantial common normative commitments than are larger ones. Other things being equal, they might also be less likely to be tolerant of dissenting practices or associations���though other things are seldom equal. But this does not alter the fact that many societies are very much like close-knit empires. Some are federations of states which retain a substantial measure of independence. Some states have so much independence that they hover on the brink of secession and independent nationhood. Which way matters go is a matter of contingency. In the end nations are not so much the product of a common history as the creators of one. And what is sometimes left unmentioned is that they might have been created very differently, since there is a great number of ways of combining peoples to make a political society���as is reflected in the frequency with which political boundaries change.--Chandran Kukathas (2003) The Liberal Archipelago: A Theory of Diversity and freedom, pp. 35-26 (emphases added).

Regular readers will have noticed that I have been reading and reflecting on Kukathas' philosophy. In the Liberal Archipelago, Kukathas identifies himself with the "the classical liberal tradition" (167) of which he is a pre-eminent theorist. Unlike most of who self-identify as 'classical liberals,' Kukathas is not obsessed with (free) markets. In fact, while I would describe The Liberal Archipelago as 'a quite Lockean work' -- with its emphasis on moral diversity, mutual toleration, the significance of conscience to it, and the focus on association and exit --, it does not obsess over property rights at all. And this hints at another important deviation by Kukathas from classical liberals, who inherit (recall) the assumption of harmony of interests from nineteenth century liberalism. At heart, Kukathas' position is straight-forward: we inevitable disagree about moral matters and the relative rankings we give them, and so the best thing we can do is to associate generally with the like-minded and find a modus vivendi with those that are indifferent to us, or worse. The main proper function of the state is to facilitate such modus vivendi in order to instantiate a cosmopolitan ideal.

Now, much of The Liberal Archipelago engages in moral argument often through the lens of (or constrained by) feasibility to defend such modus vivendi. If you think this is too thin, then in the conclusion of the work, Kukathas concedes that "the point of theorising the liberal state in terms of an archipelago of loosely associated authorities, is not that this fully captures an actual liberal state, or perhaps even a possible liberal state, but that it identifies an important dimension of it��� one which connects up with particular values end or concerns, even if it does not embrace every aspect of, or aspiration found within, the liberal state." Fair enough. My interest here is not, in the first instance, with that important dimension, but with a kind of recurring motif through the work on the nature of politics. For, to speak bluntly, Kukathas does not only repeatedly diagnose (perhaps with a hint of melancholy) rent-seeking behavior and elite capture by various social elites (as Marxists (recall) also emphasize), but at times he also slides into an elite theory of politics (that one may associate with names like Mosca, Michels, Pareto, Burnham, Aron, etc.--although none of them are mentioned in the book) The quoted passage above illustrates what I have in mind.

Now, Kukathas is not the first classical liberal with such a view of politics. And I think it is important to distinguish him, at once, from somebody like (the public choice theorist) Richard Wagner who doesn't only use such an elite theory of politics sociologically, but also (repeatedly) endorses (recall here) the idea (to put it politely) that eggs need to broken in order to make an omelet. (Non trivially Wagner also draws on Schmitt.) Kukathas is not inclined to do so because he quite clearly thinks that the means (e.g., broken eggs) fail to be justified by the ends, but also in virtue of the means tend to produce outcomes hat are not worth having (indirectly more broken eggs). So, let's stipulate Kukathas is primarily interested in the elite theory of politics as a descriptive or sociological theory.

The problem for a reader of Kukathas is that it's not clear how the normative project fits with his elite theory of politics. I have two related concerns. First, the kind of political society Kukathas advocates requires political agents with a great deal of skill to pacify social disagreements (and to set up institutions -- forms of federalism, power sharing, etc. -- that would facilitate this) and whose characteristic quality is to promote social restraint and mutual indifference. Second, it is not obvious elite agents (of the sort that Kukathas posits in his sociological theory of politics) have an interest in pursuing the ideal, or at the least the dimension of that ideal, that Kukathas' theory prescribes. This is something Kukathas repeatedly observes himself when looking at elite agents among minority groups throughout the book.

My concern is not that Kukathas lacks a theory of transition to get from a sub-par status quo to the more normatively better political place he advocates. (I do think that's a problem, too.) But rather, that even by his own lights there is no reason to think any political agent that really matters politically by his lights would pursue his ideal.

At this point, Kukathas or somebody invested in defending him, might say, look: just like free markets require a certain amount of restraint by elites not to meddle in them and to focus on the institutions (rule of law, anti-trust, human capital, etc.) to keep the market order going and growing, the liberal archipelago also requires, as Kukathas emphasis throughout, civility and some such such restraint (and background activity to promote it). Arguably something like this insight is the great truth in common preached by Mencius, Machiavelli and (Kukuthas' key thinker) Hume. As Foucault would with the eighteenth century this became a matter of scientific valediction.

Now, I do not want to deny that this response is realistic (I included Machiavelli for a reason there); in practice such social restraint is sometimes visible temporarily in elites (because of domestic or international circumstances). The very mechanism that allows elites to benefit from the growing pie of a market order also allows them to benefit from the fruits of modus vivendi. But it also makes such elites sitting ducks politically when new upstarts come along to deny them these benefits. So, a politics that requires elite self-restraint is, thus, inherently crisis ridden (as liberalism is), especially if (as Schumpeter and others have noted) the mechanism of elite selection in liberal democracy has little connection to the requirements on politics that follow from normative theory.

Perhaps, the periods of lucky tranquility between crises is then the best one can hope for (qua liberal with realist sensibilities).

March 6, 2023

On Knowing that Imperialism is Bad, Grotius and Plutarch

It's nice to see Grotius reject natural inequality (of the Aristotelian sort used by Sep��lveda (recall here)); and also to see him reject civilizational missions as a proper justification of imperialism. I re-encountered the second half of this passage (from Plutarch onward) as a frontispiece to Chandran Kukathas' (2003) The Liberal Archipelago. Before I continue I should acknowledge that I am too aware of the work of Barbara Arneil and Martine Julia van Ittersum, to use this passage to vindicate Grotius from the charge that he was an enabler of settler colonialism (both as a paid lawyer and in his more independent writing). So if you are a debunker of great, dead men don't feel you need to be on guard in what follows (not the least because there may well be a hint of sarcasm at the end of the passage because it is unlikely Grotius treats Spanish theologians -- how rational they may be -- really as authoritative).

I find passages like this useful because they undermine the pseudo-sophistication of what I (recall) call 'modern historicism. Modern historicism is constituted by three claims: first, our minds are "socially conditioned." Second, while we, too, will make socially conditioned moral mistakes, we are the products of moral progress or "Enlightenment." Third, some mechanism of historical change, even improvement, is required. In practice, modern historicism is trotted out to excuse the mistakes of the past and to re-affirm our (moral and intellectual) superiority.

For, what's really neat about about the passage quoted at the top of the post is that for Grotius the civilizational argument that purportedly justifies imperialism -- one I was taught was only really invented in the Victorian age, and that one could trace back (recall) to Hume -- is already very old and has been debunked before. Plus ��a change, plus c'est la m��me.

Now the version of the passage that Kukathas cites is translated (in 1916) by Van Deman Magoffin edited by James Brown Scott (here). Somewhat annoyingly the editorial footnote suggests that the passage from Plutarch is on his life of Alexander. The Latin facing text suggests correctly, as does Hakluyt's translation, it's from Plutarch on Pompey (70.3). I quote it in the translation from Bernadotte Perrin.

Now, the wider context here is the Roman civil war (we're on the eve of the battle between Caesar and Pompey) and the self-inflicted implosion of the Roman republic. The romans could have quietly govern and enjoyed "what they had conquered, the greatest and best part of earth and sea was subject to them, and if they still desired to gratify their thirst for trophies and triumphs, they might have had their fill of wars with Parthians or Germans." So, Plutarch's point (and one kind of echoed by Machiavelli long after him) is that the Roman republic could have brought good government (i.e., low taxes, respect for property rights, etc.) to conquered nations, and continued their imperial conquests. But the desire for glory meant an unwillingness to share victory with purported equals. That is, Plutarch defends a kind of manifest destiny for the Romans which is to bring (softly: Greek) civilization to the barbarians (after the Greeks civilized their rulers), as Alexander had done before them.

Grotius has turned Plutarch's "���������������� ������� ������������� �������� ����������� ������� �������������������� ������������������ ����� ������������������" into ���������������� �������������������� ���������������� ����� ������������������, and so misrepresented (or misremembered) him for his own ends. When I realized this I was modestly disappointed. It would have been nice if Plutarch had anticipated Grotius' point, although it's undeniable that Plutarch clearly recognizes that often greed often is the real source of purportedly civilizing missions, even ones he endorses.

March 3, 2023

On MacAskill, What we Owe to the Future, pt 6; in which I diagnose (with help from Kukathas) a different kind of repugnance.

In rejecting the understanding of human interests offered by Kymlicka and other contemporary liberal writers such as Rawls, then, I am asserting that while we have an interest in not being compelled to live the kind of life we cannot abide, this does not translate into an interest in living the chosen life. The worst fate that a person might have to endure is that he be unable to avoid acting against conscience. This means that our basic interest is not in being able to choose our ends but rather in not being forced to embrace, or become implicated, in ends we find repugnant.--Chandran Kukathas (2003) The liberal archipelago: A theory of diversity and freedom, p. 64.

This is my sixth post on MacAskill's What We Owe the Future. (The first here; the second one is here; the third here; the fourth here; the fifth here; see also this post on a passage in Parfit (here.)) I paused the series in the middle of January because most of my remaining objections to the project involve either how to think about genuine uncertainty or disagreements in meta-ethics that are mostly familiar already to specialists and that probably won't be of much interest to my regular readers. I have also grown uneasy with a growing sense that longtermists don't seem to grasp the nature of the hostility they seem to provoke and (simultaneously) the recurring refrain on their part that the critics don't understand them.

While reading Kukathas' The liberal archipelago (unrelated to EA and longtermism), I was triggered by the passage quoted at the top of the post. (Another win for the associative mechanism; from Kukathas' use of 'repugnant' to Parfit's 'repugnant conclusion' and back to What We Owe the future.) What follows is unlike the detailed textual and conceptual scrutiny I gave to MacAskill's book in earlier digressions.

Before I get to that, for my present purposes I can allow that Kukathas is mistaken that the worst fate that a person might have to endure is that a person be unable to avoid acting against conscience. Maybe this is just a very bad fate (consider, as Adam Smith suggests, being framed and convicted for murder one didn't do; or being tortured for no good reason, etc.) All I stipulate here is that Kukathas is right that being (directly) implicated in bad ends is really very bad. This is, in fact, something that seems to be motivating longtermists and compatibly with their official views. While 'repugnant' is a good concept to use here, having one's conscience violated is, in turn, a source of indignation. I think that's fairly uncontroversial and i don't mean to import Kukathas' wider political theory into the argument (although I am drawing on his sensitivity to the significance of moral disagreement).

MacAskill's book doesn't use, I think, the word 'conscience.' This is a bit surprising because the key example of successful moral entrepreneurship (his term) in the service of moral progress (again his term) is Quaker abolitionism inspired by Benjamin Lay. And Lay certainly lets conscience play a role in (say) his All Slave-keepers that Keep the Innocent in Bondage (although he is also alert to the existence of hypocritical appeals to conscience). It's also odd because one gets the sense that MacAskill and many of his fellow-travelers are incredibly sincere in wishing to improve the world and do, in fact, have a very finely honed moral sense (and conscience) despite arguing primarily from first principles, and with fondness for expected utility, and about (potentially very distant) ends.

Now, it's not wholly surprising, of course, given his (defeasible) orientation toward total wellbeing that MacAskill is de facto attracted to that conscience is not high on his list. (A "conscience utilitarianism" just doesn't get us on the right path from his perspective.) In fact, in general the needs and views of presently existing people are a drop in the bucket in his overall longtermist position. But this lack of attention to the significance of conscience also leads to a kind of (how to put it politely) social even political obtuseness. Let me explain what I have in mind in light of a passage that expresses some of MacAskill's generous sentiments. He writes,

The key issue is which values will guide the future. Those values could be narrow-minded, parochial, and unreflective. Or they could be open-minded, ecumenical, and morally exploratory. If lock-in is going to occur either way, we should push towards the latter. But transparently removing the risk of value lock-in altogether is even better. This has two benefits, both of which are extremely important from a longtermist perspective. We avoid the permanent entrenchment of flawed human values. And by assuring everyone that this outcome is off the table, we remove the pressure get there first���thus preventing a race in which the contestants skimp on precautions against AGI takeover or resort to military force to stay ahead.

Now, as I have noted before, MacAskill isn't proposing anything illegal or untoward here. His good intentions (yes!) are on admirable display. But it is worth reflecting on the fact that he or the social movement he is shaping (notice that 'we') is presuming to act as humanity's (partial) legislator without receiving authority or consent to do so from the living or, if that were possible, the future. (He is acting like a philosophical legislator in the tradition of Nietzsche and Parfit while trying to shape actual political outcomes.) And he is explicitly aware that this might well generate suspicion (which is, in part, why transparency and assurance are so important here).* One suspicion he generates is that he will promote ends and means that go against the conscience of many (consider his views on human enhancement and what is known as 'liberal eugenics').

So, while MacAskill is explicit on the need to preserve "a plurality of values" (in order to avoid early lock-in), that's distinct from accepting deeply entrenched moral pluralism--this means tolerating, at minimum, close-minded and morally risk-averse views. MacAskill does not have a theory, political or social, that registers the significance of the reality of such entrenched moral pluralism and the political and inductive risks (even backlash) for his project that follow from it. I don't think he is alone in drifting into this problem: variants of it show up in the technical version of population ethics and in multi-generational climate ethics, and other fundamentally technocratic approaches to longish term public policy. That is, it is not sufficient to claim to be promoting "open-minded, ecumenical, and morally exploratory" values, even reject premature lock-in of "a single set of values," if one never shows much sensitivity toward those that seriously disagree with you over ends and means.

In addition, to feel unseen and unacknowledged is a known source of indignation. MacAskill's longtermism constantly flirts with lack of interest in taking into account the needs and aspirations of those whose wellbeing it aims to be promoting. But even if that's unfair or mistaken on my part, given that MacAskill really doubles down on the need to promote "desirable moral progress" and tying "moral principles" that are thereby "discovered" to a "more general worldview," it is entirely predictable that he will advocate for ends and means that many, who reject such principles, will find repugnant, and a source of indignation. As, say, Machiavelli and Spinoza teach this leads to political resistance, and worse.

*Yes, you can object that the suspicion is officially at a less elevated level (the risk of AGI value lock in or conquest), but he is effectively describing a state of nature, or a meta-coordination problem, when it comes to dealing with certain kind of existential risk.

March 2, 2023

The story starts with a stolen Maupertuis (III); in which some of the main characters reveal themselves

Last week (recall) I returned a stolen Maupertuis to The Institution of Civil Engineers (hereafter: ICE) Library in London. During my visit, while I was admiring a beautiful copy of the third Edition of Newton's Principia, the librarian, Debra Francis, called my attention to a four page manuscript wedged in the first few pages of this Principia. I very quickly decided that it was probably an eighteenth century manuscript because of the paper, ink, and notation/diagrams which looked familiar. (It's immediately made clear we're dealing with falling bodies.) So, while still in the library I sent pictures of it to Niccolo Guicciardini and then to Scott Mandelbrote, George Smith, and Chris Smeenk. Debra and I spent a few minutes on the manuscript which is in English. But most of our attention was devoted to figuring out the provenance of Principia at ICE. As we now know (recall yesterday's post) the ms was found in the Thomas Young's copy of the Principia.

At this point it would be useful to say why I jumped to the conclusion it was an eighteenth century manuscript and perhaps not insignificant, and why I sent the manuscript to these four scholars. [If you are impatient to find out the big reveal, jump to the paragraph below that starts with: "it turns out"....] For, while I have published quite a bit on Newton, I don't usually spend my time looking at manuscripts and thanks to the internet I barely spend any time in special collections anymore. However, between 1993 and 1996 or so my earliest academic experience involved spending multiple Summers in the Huygens archives in Leiden while George Smith and I were working on our project reconstructing Huygens' empirical argument against universal gravity. At the time I was lucky that Joella Yoder (the world's leading Huygens scholar) often overlapped with me in Leiden, while she was cataloging the Huygens' papers at the Leiden University library. She basically gave me on the job training in archival research. Along the way, and with help of many kind archivists and librarians, I was exceedingly lucky in discovering previously unknown material and rediscovering maps (see here, pp. 93-97 & here, pp. 51-55) important to our argument (the forthcoming paper is archived here).* But while this is rich experience, I wouldn't trust myself to know the difference between, say, a forgery or a real Huygens ms. However, I do know by acquaintance what paper and ink of the era looks like.

Second, I have read the Principia three times. Once as an undergrad in the second semester of George Smith's famous Newton course at Tufts University. Once, but in much less detail, with Howard Stein in graduate school in his course on the history of space-time theories. And then again in great detail with Chris Smeenk when we wrote a Handbook article on Newton's Principia. There are a whole range of diagrams and formulations that are distinctive to the Principia because while Newton was building on the work of others, he was also innovating mathematically in it (or drawing on then still secret innovations). But to simplify greatly, while Newton's methods, results, and theories shaped subsequent research, Newton's notations and his presentation of the material are rather distinctive (and were displaced within a century); it has its own vernacular. To give a very low-level example: in Newton the second law is a proportionality (and not an equality such as F=ma). And again, because I rarely work with the Principia (and, as historians of physics go, a below average mathematician), I wouldn't trust myself to identify a passage with any particular proposition of the Principia without double checking a few times.

Now, Niccolo Guicciardini (Milan) is a historian and philosopher and a specialist on Newton's mathematics (and physics!) and who also has deep knowledge of Newton's manuscripts. He is also very generous with his time, and he does not make one feel silly if one reveals one's ignorance. (He was an important interlocuter to me when I developed my interpretation of Newton's philosophy of time and then again, when I responded to Katherine Brading's excellent criticism [see also here] of it.)+ So, he was the first person I thought of. But, as I reflected on what I had seen, I figured it might be useful for somebody to be able to visit the ICE library to inspect the manuscript in person in London. So, that's why I thought of Scott Mandelbrote in Cambridge, who among his many other intellectual virtues, is one of the leading scholars of Newton's manuscripts, including the paper, watermarks, (etc.). And I sent it to Smith and Smeenk because I hoped they would get a kick out of it, and I figured they might recognize the material that's being discussed in the manuscript much more quickly than I would.

Much to my joy Niccolo almost immediately responded to my email. And rather than pointing out my obvious mistake -- 'why bother me with this juvenilia; clearly a school boy exercise; didn't you notice the 19th century notation?' -- he wrote me back to congratulate me on the manuscript which was previously unknown to him. He then went on to say, "I might have seen the hand before ��� intriguing indeed." And at that moment I knew the story of 'my' stolen Maupertuis would have an interesting afterlife. In a subsequent email he warned me that was not sure about identity of the author and also that it may take a while before he would get back to me due to a family holiday. Okay, so much for set up.

It turns out that Guicciardini and Mandelbrote almost immediately set to work to identify the author, and they are so confident of the author's identity that Niccolo has informed the ICE library of it on March 1. They think the hand is Henry Pemberton���s--the editor of the third edition! Now, there are not many known manuscripts by Pemberton. But, as I learned from Niccolo, he has a very distinctive way of writing "this." You can see this on p 2 of the manuscript that I have reprinted below and compare it to a letter by Pemberton to Newton (9 February 1725; Cambridge UL, MS Add. 3986.7, fol 1r-1v) that Niccolo shared with Debra Francis and myself.

So, let's connect some dots. The manuscript is in the hand of Henry Pemberton (1694 ��� 1771), who was the editor of the third edition of the Principia--that is the version of the copy that Tomas Young owned and that was donated to ICE library. So, this leaves some open questions:

How did Thomas Young acquire this copy of the Principia and the Pemberton ms?

A neat, perhaps too neat, hypothesis is that ICE library actually owns Pemberton's own copy of the edition of Principia that he edited. And so that Pemberton himself inserted the manuscript in his copy of the Principia. This would at least explain how the manuscript ended up in the ICE library copy without having to posit a complex further web of linkages. However, we know that mathematical manuscripts circulated through the eighteenth century. (Well I did not know much about that, but Niccolo reminded me.) And it's also possible that the Pemberton manuscript and Thomas Young's copy of the Principia were brought together by Young himself.

2. Did Young ever use the Ice Libary Pemberton ms.?

3. What are the contents of the ICE library Pemberton ms.? About this more soon.

4. And can the contents help explain why Pemberton wrote this ms.? As we shall see, this will lead us to some outstanding historical puzzles and some major intellectual controversies. Stay tuned!

*Pro tip: befriend the retired archivist who happens to be in the library with you.

+Somewhat oddly, the Wikipedia page of Guiccardini does not mention the Sarton Medal he received in Ghent in 2011/12!

March 1, 2023

The story starts with a stolen Maupertuis (II)

Last week (recall) I returned a stolen Maupertuis to The Institution of Civil Engineers (hereafter: ICE) Library in London. During my visit, while I was admiring a beautiful copy of the third Edition of Newton's Principia, the librarian, Debra Francis, called my attention to a four page manuscript wedged in the first few pages. The manuscript was in English and seemed to be written by somebody familiar with the mathematics of the Principia. It looked 18th century to me. So, while still in the library I sent pictures of it to Niccolo Guicciardini and then, separately in a joint email, to Scott Mandelbrote, George Smith, and Chris Smeenk.

As I noted, the copy of the Principia is part of the Telford collection that originates the library and was donated by a MR. Young in 1840 (as a plaque inside the book reveals). You may recall that in my original post, I remarked "I immediately tried to remember Thomas Young's dates." Of course, I quickly googled these (1773 ��� 1829), and left it aside.

Most of my own original thoughts were about the author and contents of the manuscript, especially because I could tell Niccolo was excited to receive it. More about that soon.

After a visit to the vault (which did not contain the paperwork we were looking for), I left the library with a promise from Debra Francis to track down the provenance of 'Mr. Young's Principia.' Today she reported back to me. Well, hold on to your seats, because it's a banger:

This is from the Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Volume 1, p. 11 (see here).

Thus, it seems pretty clear that this is referring to the Thomas Young, who indeed had a brother (and nephew) called Robert Young who seems to have survived him (and seems to have died around 1850). So, the plot thickens. And in my next installment we'll return to the manuscript, its author, its contents, and, of course, how it ended up in Thomas Young's personal copy of the Principia. For Niccolo had a hunch about that, that's turning out to be very fruitful...to be continued.

February 27, 2023

Hayek, Kukathas, and the Significance and Limitations of Social Theory

Yet agreement between Hayek and the dominant strand of liberal theory may not be quite so easily secured. For a great deal turns on what is understood by a modus vivendi, and thought necessary to secure it. For Gutmann and Larmore, a liberal modus vivendi may well involve the growth of the mechanisms of participatory democracy, and need not compromise egalitarian ideals. A Hayekian conception of the liberal order as a modus vivendi, however, would not be of this nature. The conclusion he draws from his social theory is that a liberal order must be ruled by a limited government whose primary task is to maintain the framework within which individuals and groups may pursue their respective aims, regardless of the shape the resulting society assumes.

Rawls, however...explicitly rejects the idea of a modus vivendi. For him, what is needed is a political conception of justice which will command the allegiance of a diversity of moral viewpoints in a pluralist society. Only such a public philosophy which was able to sustain an 'overlapping consensus' of views would ensure social unity in 'long run equilibrium'. A modus vivendi would amount to little more than a temporary truce, in which time the more powerful interests would be able to marshall their forces, later to impose their own attitudes upon all. This contrasts with Hayek who sees social stability as possible only under political institutions which removed social justice from the agenda of politics.

This lack of agreement does not, however, reduce the interest of Hayek's contribution to liberal theory. Indeed, it suggests one way liberals may approach the problem of dealing with differences that divide them: by returning to issues in social theory. His work deserves examination because he draws attention to the need to consider the nature of society and the way in which this constrains our choice of political principles. For, if Hayek is right, many kinds of principles may be ruled out as unworkable. In other words, the circumstances of justice need much more careful investigation than they have been given.

Hayek's endeavours, while they have not succeeded in establish��ing a coherent liberal philosophy, do push contemporary liberal theory in a promising direction. For they show, first, that the defence of the liberal order need not assume that man is an isolated, asocial, utility maximizer: the defence of liberalism can, and should, be grounded in a more plausible account of man and society. And they suggest, secondly, that, while it will prove difficult to establish philosophical foundations for liberal rights, or a liberal theory of liberty, an understanding of the nature of social processes may offer a surer guide by telling us what kinds of rights and liberties cannot be adopted if the liberal ideal is to survive.-- Chandran Kukathas (1989) Hayek and Modern Liberalism, pp. 227-228. [Emphasis in original]

[If you are impatient you can skip the first four autobiographical paragraphs of today's digression.] Because I never went through a libertarian phase (and where I grew up these barely existed then), I am not quite sure when I first encountered Hayek's name and when I first read him. I do know that when I entered graduate school at age 24, I was aware of some of the features of Hayek's 'knowledge problem' because I briefly tried -- without success -- to get others in my graduate cohort interested in Hayek as an epistemologist in light of Hayek 1945. But I am really unsure how I picked this up. Between college and graduate school I read anything that happened to come my way or encountered in bookstores so I'll leave it to chance.

Because I ended up writing a PhD on Hume and Smith's philosophy of science, I did end up reading some of Hayek's writings on the Scottish Enlightenment. During my PhD, I also read the Road to Serfdom (which left me unmoved) and The Sensory Order (which was astonishing, and I was shocked nobody else I knew had read). But because I was not especially interested in spontaneous order or a deep dive into libertarianism (beyond Nozick) my knowledge of Hayek was superficial.

This started to change near the end of my PhD, around 2001, when the historians of economics, David M. Levy and Sandra Peart, started to invite me to their annual workshop on the preservation of the history of economics. Peart was working on her excellent edition of Hayek on Mill. David knew his Hayek and could easily make him philosophically interesting to me. (Recently David has been sharing his excitement about the development of modal logics by nineteenth century economists who moonlight as logicians!) Through them I met Erik Angner who was very interested in Hayek's theory of cultural evolution (a topic I was then very interested in), and I eventually read his wonderful monograph on Hayek and natural law.

I mention all of this because after I did start reading Hayek, I actually thought of Hayek as a weird Kantian or neo-Kantian. When I first mentioned this to people with a philosophical interest in Hayek this was often dismissed (such people treated him as more as a follower of Hume). So, I was quite pleased back when I read Kukathas' book the first time (about two decades ago) that Kukathas argues for Hayek's Kantianism in great detail (alongside Hayek's debts to Hume). And not surprised when decades later I read Foucault (who historically precedes Kukathas by a decade) on the significance of Kant/Kantianism to Hayek and other neoliberals in his biopolitics lectures.

Anyway, above I quote the final paragraphs of Kukathas' wonderful book, which manages to juggle quite a few balls apparently effortless at once: it is a careful study of Hayek as a systematic thinker; it locates Hayek in debates within liberalism (not the least through a detailed comparison with Rawls) and between liberalism(s) and its/their critics. Along the way, readers also get a judicious account of why it is misleading to treat Hayek as an (indirect) utilitarian. And while Kukathas is respectful of Hayek, as the quoted paragraph suggests, he argues at length that Hayek is incapable of reconciling the Kantian and Humean strands of his own theory.* Okay, so much for set up.

One important contribution of Kukathas' book is to illustrate the value of social theory to political philosophy even among those who think of political philosophy as an 'ethics first' or 'justice first' enterprise. Part of that use is hinted at in the closing paragraphs quoted at the top of this post: first, a social theory provides us with the content in a feasibility or aptness constraint. Let's call this a 'negative use of social theory' in which social theory is used (with a nod to 'ought implies can' perhaps) to rule out or block certain normative theories (or the principles on which they rely) because they are literally impossible for beings like us, once we're more informed about who we are (by social theory). Of course, unrealistic or unfeasible models or theories may still be useful in some way or another -- not the least as paradigms that discipline a field --, so one should not expect to use social theory (which often blends normative and empirical features in complex ways) as a hammer to destroy viewpoints one wishes to reject.

Second, and this is a positive feature, social theory can provide one with a philosophical anthropology that allows one to recast one's political vision and/or normative theories. In Hayek's case this also (third) means that many typical criticisms of liberalism (familiar, say, from Karl Polanyi (who goes unmentioned), Alisdair MacIntyre, various communitarians and Marxists (etc.) are disarmed in advance because the anthropology supplied by Hayek's social theory actually is not the Robinson Crusoe one -- "isolated, asocial, utility maximizing" -- usually criticized by critics of liberalism; if anything Kukathas' Hayek (and I agree) is not very far from Hegel, although as Kukathas notes with some key differences.

But, unless I missed it, Kukathas does not define what he or Hayek means by 'social theory' (something on my mind due to failed efforts to do so while teaching undergrads). Hayek does give us some material to work on this. For example, in (1967) in "Notes on the Evolution of Systems of Rules of Conduct: The Interplay between Rules of Individual Conduct and the Social Order of Actions," Hayek writes the following:

The whole task of social theory consists in little else but an effort to reconstruct the overall orders which are thus formed, and the reason why that special apparatus of conceptual construction is needed which social theory represents is the complexity of this task. It will also be clear that such a distinct theory of social structures can provide only an explanation of certain general and highly abstract features of the different types of structures (or only of the ���qualitative aspects���), because these abstract features will be all that all the structures of a certain type will have in common, and therefore all that will be predictable or provide useful guidance for action.--p. 283 in The Market and Other Orders, edited by Bruce Caldwell.

On Hayek's view social theory is, thus, engaged in conceptual construction. And it aims to construct what he calls an 'overall order.' (There are distinct resonances here with the morphological project of the ordoliberal, Eucken.) These overall orders are "systems of rules of conduct" which "will develop as wholes" and on which a certain kind of "selection process...will operate on the order as a whole." Now, clearly this conception of social theory is, while capable of objectivity, itself partial to Hayekian projects (he goes on to claim that "of theories of this type economic theory, the theory of the market order

of free human societies, is so far the only one which has been systematically developed over a long period"), so I don't mean to suggest Hayek's idea of 'social theory' ought to generalize to all social theory.

Now, crucially, Hayekian social theory provides one with functional explanations of social order(s). Hayek is very explicit about this on the following page (p. 284). It may require auxiliary sciences to do so (Hayek is discussing the rule of evolutionary social psychology in context). And one way it offers such a functional explanation is to make clear the "interaction between the regularity of the conduct of the elements [or individuals] and the regularity of the resulting structure." (289)

I call it 'Hayekian' social theory because one of the other "tasks" he ascribes to it is to explain the "unintended patterns and regularities which we find to exist in human society." (from Hayek (1967) "The results of human action but not of human design." p. 294 in The Market and Other Orders.) Obviously, that may be incompatible with a social theory that has a different focus, although Marx is clearly interested in features of such a social theory.

So, why do I mention this? Before I answer that let's stipulate that Hayek's social theory is coherent. I have two reasons. First, even coherent, it is not entirely obvious what the status of the fruits of Hayekian social theory are. What kind of impossibility is proven by social theory if it has a Hayekian cast? This is not obvious. (In part this is not obvious because the empirical basis of social theory is not easily disentangled from its normative commitments.) I don't see how Hayekian social theory can rule out orders constructed on principles very different than Hayekian social theory, even if one can suspect that these will not be functional in the way that (say) spontaneous orders will be. This depends on plasticity of humans but also on the possibility of social structures with different kinds of social rules. I don't think this paragraph undermines Kukathas' particular argument because he shows how much Rawls and Hayek agree in their commitments.

Second, Hayekian social theory inherits from 19th century historicism (and some aspects of the Scottish Enlightenment) the idea of social wholes (that are constituted by their system of rules). Now, Hayek acknowledges that (say) a historian or social scientist may well do his or her job without embracing social wholes. His is not an organicist theory, and since social pluralism is -- as Kukathas reveals -- kind of bedrock in his theory it would be odd to attribute organicism to Hayek. However, it is not obvious why in a world constituted by social pluralism of different sorts -- and with non-trivial barriers that would facilitate differential and distinct selection -- we would find such social wholes even in (say) places that share non-trivial social commonalities. If human law or force is part of the selection process we should in fact expect greater diversity. In fact, I am echoing here Hayek's friend, Eucken, who clearly thought that Hayek's expectation of such social wholes was only so in theory, but that in practice one could find a rich diversity of social orders (based on a limited number of morphological elements).

Let me stop there. I don't mean to suggest these are fatal objections to Hayek's theory. But if we look forward to Kukathas' Liberal Archipelago it helps explain Kukathas' non-trivial distance from using Hayekian social theory despite Kukathas and Hayek sharing a deep debts to Hume.

*I should say while I agree with Kukathas' analysis of Hayek, there is wiggle room for a Hayekian. Kukathas acknowledges that Hayek is not especially interested in 'moral justification.' (p.3) But on my reading of Kukathas' argument the Kantian parts that cause trouble for the coherence of Hayek's system (those in his account of the rule of law that enter into his normative claims (p. 19)) all involve such justification.

February 24, 2023

The story starts with a stolen Maupertuis

Actually, the story starts with me buying a copy of Maupertuis' (1738) La figure de la terre at auction online. I am a modest rare book collector; my principle of collecting is 'works that intersect with my scholarly research in neat ways' (all other things being equal, which is not always -- -- the case). So that means that unlike many collectors, I am not always after the first edition of a work and do not mind copies that show sign of some scholarly use (which also means I can afford them more easily).

Now, my first scholarly projects starting with George Smith were on the Huygens-Newton debate over universal gravity and the shape of the Earth, and the measurements that settled it. Maupertuis' measurements in Lapland -- the title page of the 1738 work prefers 'polar circle' -- were part of the evidence that helped resolve the debate. While others (Maglo, Terrall, Shank, etc.) would publish with more detail on La Figure, I used this work by Maupertuis to make some modest, albeit distinctive claims about the philosophical particulars of Adam Smith's History of Astronomy.

The pictures of the lot suggested a very clean copy, but one with a modern binding. Much to my surprise the bidding for it remained relatively calm even in the final minutes. And so for under 500��� (generally the most I am willing spend on a rare book) I was the proud owner of a work that is a joy to read, has an interesting story, and that shows up in non-trivial places in my own scholarship. I was elated! The seller sent it off with tracking, and the book arrived after a few days. I had last held a physical copy in my hand over twenty years ago in Chicago (presumably at the Newberry library, but I just noticed there is also a copy in Regenstein so maybe there).

After opening the package, I opened the book and I had my first modest disappointment. The neat map I remembered at the front of the book was not there. My spirits started to deflate, but after looking through the book I found it at the back. (See here for a picture of the map at Gallica.) Interestingly enough, the copy of the English translation in the British Library, which seems to be one used by Google to scan it also has the map in front, whereas the French version has it in back (but the reproduction is badly done)! So, I wondered if I had misremembered and had only looked at the English translation. More on this below.

However, when I started to look through the book more slowly I had a true shock. There was an impressive library stamp on the page facing the frontispiece with "The Institution of Civil Engineers" and an address at "25 Great George Street, Westminster" in London. (See the picture below this post.) Now, I have bought books at auction before that had impressive library stamps in them. I always do due diligence before I bid and check out the provenance. Usually I find that the book had belonged to a seminary or school library that had closed or merged. Most sellers show a library stamp in the pictures that the seller usually supplies in auction. How could I have missed this?

I went online to check the lot I had bought and to my shock there was no picture of the stamp! I then went online to look for the Institution of Civil Engineers library, and found an impressive website, which suggested the library was flourishing although it had moved a few doors down. I checked the catalogue and it showed a copy of the book I was holding in my hand. At that moment, I realized I had almost certainly a stolen book in my hands (although part of me hoped they had sold off a duplicate).

I knew I had to move quickly, so I immediately wrote the auction house with my suspicion (so that they would keep my payment in escrow). (It was Friday afternoon after hours for the auction house so I knew I would not hear back before Monday at the earliest.) I then contacted the seller/dealer through the auction house message system in France; he responded quickly but in a dismissive fashion. (I return to that below.)

I decided to call the ICE library. The person who picked up the phone was a librarian. I quickly explained the situation. It turns out the ICE library is supposed to have two French copies of La Figure (one part of a special collection). While we were talking she established one of these copies was missing. I was not surprised, I was holding it! At this point I knew the book had to be returned, but I was not wholly eager to take the loss. So, I gave her my yahoo email address, but little else info about me.

However, it was time to be more assertive with the seller. In our online interactions he revealed that he had bought the book a few months ago at another (reputable) auction house, and that these would have been cautious about provenance. (I was stunned how little he paid!) I decided to call the specialist listed on their website. I explained the situation to him, and after some back and forth he explained that the book was bought through an intermediary as part of a much larger estate of a deceased book-dealer. So, now I knew that my seller was not himself the thief or an accomplice in selling on stolen goods, and that the book was probably missing at least since 2020 or so. (My seller had merely looked the other way downstream.) The member of staff of this auction house told me they were insured against this kind of thing. So, I decided that my seller could probably get his money back there.

By monday, after some further communication between us, my seller agreed not to accept my money if I returned the book to the library in London. And much to my relief my auction house agreed to this approach provided I would supply them with pictures of the stamp and of the book, as well as a letter of the ICE library and me handing it back. I contacted my new librarian friend at ICE, and she was eager to facilitate this.

So, this morning I went to the lCE library right next to Parliament. I was stunned by how beautiful it was. And I was welcomed by my new librarian friend, who decided to give me a grand treat. First I was given a tour of the library and told its history. I was shown some of the special collections. And then we did the hand-over. But as we did the hand-over she showed me the copy of the 1738 La Figure from their special collection. It was much less pristine copy of the book than 'mine' that I was returning. But as we opened it, it did have the map on the facing page of the frontispiece just as I had remembered!

For some reason this cheered me up greatly. In part, because it created a new puzzle why did some copies have the map in front and others in the back? (And more interestingly, which one was the original and which on the possible bootleg?) I have done a modest survey online today some seem to lack the map altogether, but other library copies do have the map and there is no clear pattern whether it's in front or in the back of the book.

Now, while my librarian friend was correcting some infelicities in the letter she had made out to my auction house, I had a chance to inspect the box with the original holdings of the library donated by (if I am not mistaken) Thomas Telford. Most of the books were clearly engineering specific. But my heart started to flutter when behind the glass I saw a copy of the Opticks. Judging by its tattered spine an original fourth edition. When my librarian friend returned we opened the case and it turned to be a fragile copy of the third edition.:) [See picture below.] She had a quick peek in the catalog and informed me there should be more Newton holdings in the case. I scanned the list, and then looked more closely in the case, and immediately spotted a posthumous edition of Newton's work on fluxions. At this point, I had forgotten my misery over the Maupertuis and switched into scholar, teacher, and collector mode and started to pontificate on the significance of these holdings. Then I stopped mid-sentence, I had spotted the Principia!

When she took it out it was a pristine copy of the third edition donated by a Mr. Young in 1840. I immediately tried to remember Thomas Young's dates. I don't think I have ever held a third edition the Principia (the last one published during his life). Despite my excitement I was a bit sad there were no marginalia. However, as I was ruminating over this my librarian friend called me attention to a four page manuscript wedged in the front pages of the book. I have reproduced the first page below. (It's in English and fairly easy to follow.) I immediately took pictures of the whole manuscript and sent them to the great Niccolo Guicciardini to see if he could identify the author.

At this point my host invited me down to the basement where the members registry is held to see if we could identify which Young had donated the copy of the third edition of the Principia. (It turns out the relevant copy of the registry is in storage.) As it happens the basement office is next to the vault, and I could not resist an offer of a tour of it (including learning the escape route on the other side of the vault). For, it turns out that the library has a special collection which houses just about every important book published in the 17th century on clocks and finding longitude. So, for the next half hour I geeked out and excitedly explained the significance of each book I recognized to my patient librarian host. And I was also struck by the presence of some works wholly obscure even to a specialist. By the time I left, I forgot to send the materials to the auction house because I was thinking of new research projects.

February 22, 2023

Rawlsian Minutiae, Mill, and Free Speech

First of all, it is important to recognize that the basic liberties must be assessed as a whole, as one system. That is, the worth of one liberty normally depends upon the specification of the other liberties, and this must be taken into account in framing a constitution and in legislation generally. While it is by and large true that a greater liberty is preferable, this holds primarily for the system of liberty as a whole, and not for each particular liberty. Clearly when the liberties are left unrestricted they collide with one another. To illustrate by an obvious example, certain rules of order are necessary for intelligent and profitable discussion. Without the acceptance of reasonable procedures of inquiry and debate, freedom of speech loses its value. It is essential in this case to distinguish between rules of order and rules restricting the content of speech. While rules of order limit our freedom, since we cannot speak whenever we please, they are required to gain the benefits of this liberty. Thus the delegates to a constitutional convention, or the members of the legislature, must decide how the various liberties are to be specified so as to yield the best total system of equal liberty. They have to balance one liberty against another. --John Rawls A Theory of Justice, p. 203. {Emphasis added--ES}

At one point, in his marvelous (1989) Hayek and Modern Liberalism, Chandran Kukathas quotes from Rawls' A Theory of Justice in order to illuminate the point that "conflicts among different pursuers of values are best regulated according to principles which respect (the right to) liberty." (p. 147) Kukathas quotes the part I have highlighted and italicized. I want to call this part Rawls' "ordered conception of free speech" stance. (One might also call it 'the rule governed conception of free speech' or the 'transcendental conception of free speech' etc.) And its that highlighted and italicized material that triggered this post.

While Rawls goes on to discuss Mill's On Liberty in the next sections (on freedom of conscience), he does not comment on the fact that the ordered conception of free speech is at variance with the more tumultuous conception of free speech that is usually ascribed to On Liberty. I put it like that because I don't want to perpetuate the error that Mill holds 'a free market in ideas that will lead to truth view' although the marketplace of ideas view is even more frequently (and, as Jill Gordon persuasively argues, mistakenly) attributed to Mill (recall this post); recall also see, for example, here; here, and here.)

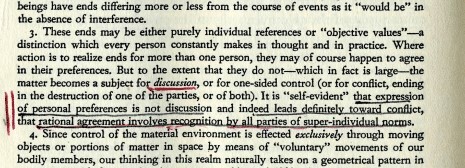

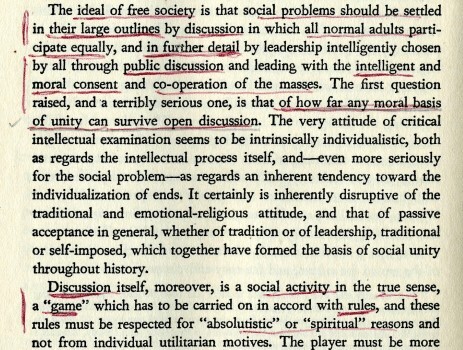

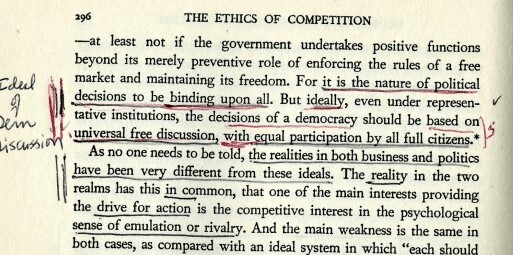

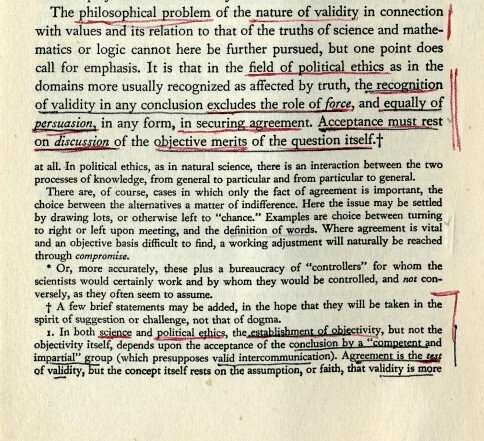

One reason to call it Rawls' account an 'ordered conception' of speech is that the value he ascribes to it is articulated in functional terms. One might say that for Rawls the intelligibility of freedom of speech presupposes that it has a certain function namely to produce 'intelligent and profitable' speech (which he may have inherited from Knight--see the second picture). Leaving aside the elitist commitments on display here (and, if one wishes, the generosity toward profit if we read him over-literally), lots of emotionally significant expressive speech clearly is not like that even if it falls short of the vituperative speech that Mill worries about. In fact, this contrast between expression and discussion is explicit on p. 346 in Frank Knight's treatment of some such contrast, and is one of the heavily annotated passages in Rawls' copy of The Ethics of Competition.*

The following is from p. 352 in Knight:

Now, before I continue, I do not want to claim that Rawls thinks governments have very broad scope to regulate speech to make it 'intelligent and profitable' or to promote the ordered conception. He may well also believe that this would be imprudent or, that the enforcement of speech restrictions, would generate concerns about violations of other liberties (privacy, assembly, freedom of conscience, etc.). And he may also think that when the government regulates speech it really is interested in content and not order (and so cannot be trusted to get this right). In fact, in A Theory of Justice Rawls is by and large not that interested in freedom of speech. But one can see why the functional significance of the ordered conception lends itself well to the rather extensive speech restrictions (in selling financial instruments, in selling pharmaceuticals, in selling tobacco, etc. ) which are quite common in the contemporary administrative state (and often ignored in recent public debates over woke and freedom of speech).

As an aside, I don't mean to satirize the ordered conception of speech. It clearly has debts to Knight's and Buchanan's diverging conceptualizations of liberalism as involving "democracy as government by discussion" that was, as I have suggested above, have been familiar to Rawls. (I also think one can extract the ordered conception from Mill's writings on representation.) I am myself not immune to the pull of the ordered conception of speech in some contexts. For example, it informs my own views on academic freedom which fundamentally involves ordered speech of different kinds (in journals, the seminar room, etc.) I also tend to suspect (echoing Iris Marion Young) that advocates of deliberative democracy and (closer to Rawls' own heart) public reason tend to be (dangerously) enthralled by the ordered conception of speech.

Be that as it may, if one works with the revised (1990) edition of A Theory of Justice, the ordered conception is less pronounced. In fact, the passage is re-written in non trivial ways. Among the most significant changes, the revised version of the passage removes 'intelligent and profitable" and the distinction between rules of order and rules on content altogether:

First of all, one must keep in mind that the basic liberties are to be assessed as a whole, as one system. The worth of one such liberty normally depends upon the specification of the other liberties. Second, I assume that under reasonably favorable conditions there is always a way of defining these liberties so that the most central applications of each can be simultaneously secured and the most fundamental interests protected. Or at least that this is possible provided the two principles and their associated priorities are consistently adhered to. Finally, given such a specification of the basic liberties, it is assumed to be clear for the most part whether an institution or law actually restricts a basic liberty or merely regulates it. For example, certain rules of order are necessary for regulating discussion; without the acceptance of reasonable procedures of inquiry and debate, freedom of speech loses its value. On the other hand, a prohibition against holding or arguing for certain religious, moral, or political views is a restriction of liberty and must be judged accordingly. Thus as delegates in a constitutional convention, or as members of a legislature, the parties must decide how the various liberties are to be specified so as to give the best total system of liberty. They must note the distinction between regulation and restriction, but at many points they will have to balance one basic liberty against another; for example, freedom of speech against the right to a fair trial. The best arrangement of the several liberties depends upon the totality of limitations to which they are subject.--John Rawls A Theory of Justice, Revised edition, p. 178. {emphasis added--ES}

I suspect part of the change of wording is due to that it is easy to abuse a purported restriction on order as a restriction on content. For, while officially dropping the distinction, the revised version leans into denying the government any significant content restrictions, by adding the point that "a prohibition against holding or arguing for certain religious, moral, or political views is a restriction of liberty." But as the highlighted part suggests, even so, the crucial element of the ordered conception of speech does remain in the revised version.

Let me close with a sociological observation. Despite the fact that advocates of public reason and deliberative democracy, which lean heavily on conceptions of ordered speech, have thriving research programs (and the former is very indebted to Rawls), it is safe to say that Rawls' conception of freedom of speech has not been as influential as other parts of his project. I have three kinds of evidence for this claim: first, in Katrina Forrester's In the Shadow of Justice, freedom of speech barely figures. (Of course, civil disobedience does!) Second, the emphasized and italicized parts of the passages are quoted very rarely in the secondary literature (although I found it in a few dissertations especially). Third, it is my perception that in scholarly and more public intellectual discussions of free speech, Rawls' shadow has not, displaced Mill. Obviously my perception counts for nothing, but I would be amazed if data crunchers could show otherwise.

*PS After reading an earlier draft of the post, David M. Levy was kind enough to share some marking up of Rawls' personal copy of Knight's The Ethics of Competition (which has Knight's earliest use of 'government by discussion' as I learned from the paper by Ross Emmett linked above). The fact that Knight treats the rules of discussion as game is important evidence for Forrester's argument on the early Rawls' interest in what is now known as neoliberalism. For some other salient to the present post's passages see these pix:

From p. 343:

Eric Schliesser's Blog

- Eric Schliesser's profile

- 8 followers