Dibyajyoti Sarma's Blog, page 43

March 20, 2015

Intersteller

Finally, I got a copy of Chris Nolan’s Intersteller. I was once a Nolan fan. I still love The Prestige. I saw The Dark Knight, Inception and The Dark Knight Rises in the theatre, first day first show. Then, somehow, I lost interest. Even the brouhaha that Intersteller made could not make me go and check out the film.

Finally, I got a copy of Chris Nolan’s Intersteller. I was once a Nolan fan. I still love The Prestige. I saw The Dark Knight, Inception and The Dark Knight Rises in the theatre, first day first show. Then, somehow, I lost interest. Even the brouhaha that Intersteller made could not make me go and check out the film. Last night, I saw portions of the film. It is long, of course. I saw the last half-an-hour with interest, without actually understanding much. But the scenes looked gorgeous, especially the wormhole, Gargantua. And the whole fifth dimension/third dimension tesseract (I know about tesseract, thanks to those Marvel Superhero movies) of a young girl’s room over and over again, was thrilling, and moderately interesting.

Then fadeout, and Coop is rescued and he is on a space station orbiting Saturn (with a scene which is a nice homage to Inception’s weird dream), and he meets his old and dying daughter. And, then, the daughter urges the father to go meet Dr Brand, still young, in a different galaxy. Because, she says, “A parent shouldn't have to watch their own child die.”

I found the dialogue very curious, as if I have heard it before. Then I remembered. This is a reworking of what King Theoden said in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers: “No parent should have to bury their child.”

Now, I could only imagine how much of the movie is borrowed, reworked upon.

PS. Talking about Nolan and neat endings, you know, Coop goes back to Brand and they meet and mate and their children/grandchildren are those ‘beings’ who created the fifth dimension/third dimension tesseract to help Coop come to space in the first place.

Published on March 20, 2015 03:53

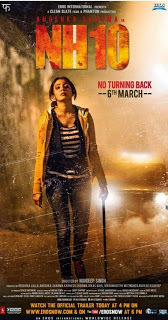

NH10

I want to go and see NH10. In a theatre. I am looking forward to it. I like the trailer, and I like the promo song, ‘chil gaye naina..’ I like action-heroine movies. I like Anushka Sharma, even after the lip-job. I loved, loved Navdeep Singh’s first film, Manorama Six Feet Under.

I want to go and see NH10. In a theatre. I am looking forward to it. I like the trailer, and I like the promo song, ‘chil gaye naina..’ I like action-heroine movies. I like Anushka Sharma, even after the lip-job. I loved, loved Navdeep Singh’s first film, Manorama Six Feet Under. When the film was released last Friday, the reviews were 50/50. The critics praised Sharma but were not sure about the screenplay, and so on. They basically had an unhappy experience. I was not sure how the film turned up.

Now, Jai Arjun Singh writes a wonderful comment piece on his blog about the film, which makes me hopeful. I trust this guy’s judgment.

Writes Singh:/

Singh’s long-overdue second film – which lived up to the expectations I had after his wonderful debut Manorama Six Feet Under nearly eight years ago – is, first and foremost, a tightly constructed genre movie, an exercise in suspense. The immediacy of the experience – being glued to the screen, holding your breath, forgetting to pick up your cold coffee, wondering if it was a good or a bad idea for this film to have an Intermission (the break provides a needed breather, but it also has the effect of toning down the intensity) – precedes everything else.

And only then, after exiting the hall and collecting one’s thoughts, does one reflect on the deeper issues being dealt with here: about the many faces and inner contradictions of a society heaving between old and new ways of life. Where a woman may have a high-paying job in a posh, gated office complex, but may still be encouraged to carry a weapon for her safety, and to anticipate and be “responsible” for other people’s criminal impulses (“Gurgaon badhta bachcha hai, toh gun mujhe hee lena hoga,” Meera says drily) – because the police can do only so much to help, and they would rather she didn’t travel alone anyway, it makes their job more difficult. (Besides, the idea of a woman driving by herself late at night discomfits them at a more primal level. Cops don’t emerge from thin air, as someone points out, they come from society and are very much part of it.) It's a world where elegantly dressed, well-spoken male colleagues may listen attentively to her presentation, but later rib her about the boss making special concessions for a woman.

MORE HERE/

Published on March 20, 2015 03:28

March 19, 2015

A Village in Lower Assam

Published on March 19, 2015 01:10

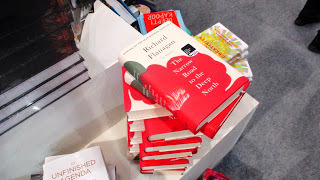

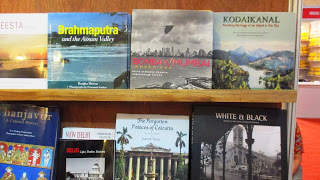

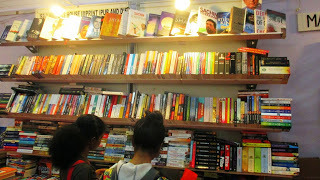

New Delhi World Book Fair 2015

Published on March 19, 2015 00:57

February 19, 2015

I was in a hotel recently. Job. It was a small, cosy spac...

I was in a hotel recently. Job. It was a small, cosy space, which had at least five mirrors. I mean, wherever you turn, an image of you will stare back. It was unnerving, almost nightmarish…

Then I found Jorge Luis Borges talking about mirrors. Then it made sense…

Says Borges: “As a small boy, whenever I saw myself reflected in a large mirror, I felt all the horror of the wraith-like doubling or multiplication of reality. Mirrors, with their never-failing mimicry, their pursuit of each of my movements, their pantomime of the world, seemed eerie to me. If a mirror hangs in a room, I can no longer be alone there: someone else is present. God created the forms of the mirror to show man that he is but a reflection, that all is vanity; this is why mirrors frighten us.”

Then I found Jorge Luis Borges talking about mirrors. Then it made sense…

Says Borges: “As a small boy, whenever I saw myself reflected in a large mirror, I felt all the horror of the wraith-like doubling or multiplication of reality. Mirrors, with their never-failing mimicry, their pursuit of each of my movements, their pantomime of the world, seemed eerie to me. If a mirror hangs in a room, I can no longer be alone there: someone else is present. God created the forms of the mirror to show man that he is but a reflection, that all is vanity; this is why mirrors frighten us.”

Published on February 19, 2015 04:19

February 18, 2015

A Boy Named Sue

“A Boy Named Sue”

Johnny Cash

My daddy left home when I was three

And he didn't leave much to ma and me

Just this old guitar and an empty bottle of booze.

Now, I don't blame him cause he run and hid

But the meanest thing that he ever did

Was before he left, he went and named me "Sue."

Well, he must o' thought that is quite a joke

And it got a lot of laughs from a' lots of folk,

It seems I had to fight my whole life through.

Some gal would giggle and I'd get red

And some guy'd laugh and I'd bust his head,

I tell ya, life ain't easy for a boy named "Sue."

Well, I grew up quick and I grew up mean,

My fist got hard and my wits got keen,

I'd roam from town to town to hide my shame.

But I made a vow to the moon and stars

That I'd search the honky-tonks and bars

And kill that man who gave me that awful name.

Well, it was Gatlinburg in mid-July

And I just hit town and my throat was dry,

I thought I'd stop and have myself a brew.

At an old saloon on a street of mud,

There at a table, dealing stud,

Sat the dirty, mangy dog that named me "Sue."

Well, I knew that snake was my own sweet dad

From a worn-out picture that my mother'd had,

And I knew that scar on his cheek and his evil eye.

He was big and bent and gray and old,

And I looked at him and my blood ran cold

And I said: "My name is 'Sue!' How do you do!

Now your gonna die!!"

Well, I hit him hard right between the eyes

And he went down, but to my surprise,

He come up with a knife and cut off a piece of my ear.

But I busted a chair right across his teeth

And we crashed through the wall and into the street

Kicking and a' gouging in the mud and the blood and the beer.

I tell ya, I've fought tougher men

But I really can't remember when,

He kicked like a mule and he bit like a crocodile.

I heard him laugh and then I heard him cuss,

He went for his gun and I pulled mine first,

He stood there lookin' at me and I saw him smile.

And he said: "Son, this world is rough

And if a man's gonna make it, he's gotta be tough

And I knew I wouldn't be there to help ya along.

So I give ya that name and I said goodbye

I knew you'd have to get tough or die

And it's the name that helped to make you strong."

He said: "Now you just fought one hell of a fight

And I know you hate me, and you got the right

To kill me now, and I wouldn't blame you if you do.

But ya ought to thank me, before I die,

For the gravel in ya guts and the spit in ya eye

Cause I'm the son-of-a-bitch that named you "Sue.'"

I got all choked up and I threw down my gun

And I called him my pa, and he called me his son,

And I came away with a different point of view.

And I think about him, now and then,

Every time I try and every time I win,

And if I ever have a son, I think I'm gonna name him

Bill or George! Anything but Sue! I still hate that name!

The song in Youtube, here.

Johnny Cash

My daddy left home when I was three

And he didn't leave much to ma and me

Just this old guitar and an empty bottle of booze.

Now, I don't blame him cause he run and hid

But the meanest thing that he ever did

Was before he left, he went and named me "Sue."

Well, he must o' thought that is quite a joke

And it got a lot of laughs from a' lots of folk,

It seems I had to fight my whole life through.

Some gal would giggle and I'd get red

And some guy'd laugh and I'd bust his head,

I tell ya, life ain't easy for a boy named "Sue."

Well, I grew up quick and I grew up mean,

My fist got hard and my wits got keen,

I'd roam from town to town to hide my shame.

But I made a vow to the moon and stars

That I'd search the honky-tonks and bars

And kill that man who gave me that awful name.

Well, it was Gatlinburg in mid-July

And I just hit town and my throat was dry,

I thought I'd stop and have myself a brew.

At an old saloon on a street of mud,

There at a table, dealing stud,

Sat the dirty, mangy dog that named me "Sue."

Well, I knew that snake was my own sweet dad

From a worn-out picture that my mother'd had,

And I knew that scar on his cheek and his evil eye.

He was big and bent and gray and old,

And I looked at him and my blood ran cold

And I said: "My name is 'Sue!' How do you do!

Now your gonna die!!"

Well, I hit him hard right between the eyes

And he went down, but to my surprise,

He come up with a knife and cut off a piece of my ear.

But I busted a chair right across his teeth

And we crashed through the wall and into the street

Kicking and a' gouging in the mud and the blood and the beer.

I tell ya, I've fought tougher men

But I really can't remember when,

He kicked like a mule and he bit like a crocodile.

I heard him laugh and then I heard him cuss,

He went for his gun and I pulled mine first,

He stood there lookin' at me and I saw him smile.

And he said: "Son, this world is rough

And if a man's gonna make it, he's gotta be tough

And I knew I wouldn't be there to help ya along.

So I give ya that name and I said goodbye

I knew you'd have to get tough or die

And it's the name that helped to make you strong."

He said: "Now you just fought one hell of a fight

And I know you hate me, and you got the right

To kill me now, and I wouldn't blame you if you do.

But ya ought to thank me, before I die,

For the gravel in ya guts and the spit in ya eye

Cause I'm the son-of-a-bitch that named you "Sue.'"

I got all choked up and I threw down my gun

And I called him my pa, and he called me his son,

And I came away with a different point of view.

And I think about him, now and then,

Every time I try and every time I win,

And if I ever have a son, I think I'm gonna name him

Bill or George! Anything but Sue! I still hate that name!

The song in Youtube, here.

Published on February 18, 2015 21:45

February 4, 2015

Book Review

I am always flummoxed when people ask me, “What your poems are about?” I do not know how to answer this question.

Now, thanks to you, Sucharita Dutta-Ashane, I can quote you and say that my poems are “wistful exploration of journeys through life, its lived realities and desired metaphors. Structured as a series of select journal entries, the poems trace a deep and long history of sorrow—acceptance—sorrow, the mind’s efforts to confront reality, the poet’s anguished heart turning into metaphor the journalist’s experiences. It presents life strung across a wire, taut, waiting to snap, perhaps, but held in place for the moment by the spine of a journal. Lyrical and “seeped in sadness”, the poems thus record stories of moments—probed, prodded, laid out bare—a journey that has to be made even if there is no destination in sight.”

Thank you for the wondrous words.

And, a thank you to you too, Arjun, for your enthusiasm, above all else.

The review is in the December 2014 issue of The Four Quarters Magazine. http://tfqmagazine.org/DUTTA-SUCHARIT...

/

The text of the review below/

Life, Inventoried

By Sucharita Dutta-Ashane

“Poetry is the journal of a sea animal living on land, wanting to fly in the air.”

-Carl Sandburg

Dibyajyoti Sarma’s Pages from an Unfinished Autobiography is a wistful exploration of journeys through life, its lived realities and desired metaphors. Structured as a series of select journal entries, the poems trace a deep and long history of sorrow—acceptance—sorrow, the mind’s efforts to confront reality, the poet’s anguished heart turning into metaphor the journalist’s experiences. It presents life strung across a wire, taut, waiting to snap, perhaps, but held in place for the moment by the spine of a journal. Lyrical and “seeped in sadness”, the poems thus record stories of moments—probed, prodded, laid out bare—a journey that has to be made even if there is no destination in sight.

“It’s just a place,

Like any other.

It may not be your destination,

But

It certainly is someone else’s.

Take a hike.

Explore the place.

You may start to like it.

There are people who did.

It is after all a destination, like any other.”

The poet is the observer and the observed, the planes of emergence and submergence fluid, continuous, the journey from the outer to the inner ruthless, deliberate, an exorcism of the soul that doesn’t bring relief.

“Oh, how sad, the old beggar

On the roadside

Naked, shivering in the cold

His head between his knees

Like a cloudless piece of sky.

In my warm clothes,

I pitied him, I stood before him

And shedding my clothes one by one

I gave them to him,

My muffler and my torn underwear.

The beggar stood up and

Elaborately put on the clothes

One piece at a time, and finally

The wristwatch. He bowed a little

To thank me, and walked away.

Oh, how sad, I

On the roadside

Naked, shivering in the cold

My head between my knees

Like a cloudless piece of sky.”

(Journal Entry: 78)

The poems negotiate ways and ways, destinations reached and breached, sometimes to find fulfilment, sometimes to forge escape routes, but the journey is unsparing. It snares the traveller, the roads wrap around one another, in the traveller’s “throbbing heart/There lies an impenetrable darkness”. There are no exits; what seem to exist are phantom promises.

“Poems are escape routes

Fire exits

Always there

To make you feel secure.

But when you need them

They bar your entry

With the stubbornness of a six-year-old

Crying for his favourite candy.”

(Journal Entry: 100)

The poet mulls over possibilities, wanders among love and loss, dedicates words to friends and lovers, to those who have inspired and those who have caused despair, deeply aware, all the while, of the pervasive transience of all that takes place; “Finally, nothing remains”. As the refrain resonates across the poems, the tone swings from despair to acceptance to intense yearning, lingering hope:

“He will come.

He won’t.

...

He won’t.

He will.

...

He won’t come.

He will.”

(Journal Entry: 51)

It is in these spaces, in the elision between hope and acceptance, in the repetitive arc of expectation and loss that the poet seems to exist. These intervening spaces spring hope and the joy of anticipation, of finding fulfilment, the intertwining, intense pleasures of loving and leaving, of remembered presence or the expectation of presence.

The poems thus carve a cyclical path, emotions beginning where they ended, the dragon gorging on its tail. The poet travels on, “through time/Through everything for which you/Once wanted to stop”, through the history that engenders them—the day’s experience, the mind’s inquest, its struggle, the meandering between thinking and just living, between distress and hope.

“In short, I’m blind

For a while now.

I’ve removed my eye-balls

And hung them on the gate.

He will walk by this way

Dazzling my sight.”

(Journal Entry: 76)

Elisions also inform the structure of this loose collection of recordings. The journal entries are numbered, though not necessarily in expected succession. What transpires in the blanks? What journeys does the poet undertake, where does the mind wander, how does it come back to the trajectory it has shaped for itself? Intense and repetitive, the general theme of love and yearning is expressed by the poet with sincerity of tone and language that leaves behind melancholy, as also a deeply pervasive mood of knowing that

“Dreams inhabit a different world

Beyond us and surrounding us

We live in glass jars, made of dreams.”

Now, thanks to you, Sucharita Dutta-Ashane, I can quote you and say that my poems are “wistful exploration of journeys through life, its lived realities and desired metaphors. Structured as a series of select journal entries, the poems trace a deep and long history of sorrow—acceptance—sorrow, the mind’s efforts to confront reality, the poet’s anguished heart turning into metaphor the journalist’s experiences. It presents life strung across a wire, taut, waiting to snap, perhaps, but held in place for the moment by the spine of a journal. Lyrical and “seeped in sadness”, the poems thus record stories of moments—probed, prodded, laid out bare—a journey that has to be made even if there is no destination in sight.”

Thank you for the wondrous words.

And, a thank you to you too, Arjun, for your enthusiasm, above all else.

The review is in the December 2014 issue of The Four Quarters Magazine. http://tfqmagazine.org/DUTTA-SUCHARIT...

/

The text of the review below/

Life, Inventoried

By Sucharita Dutta-Ashane

“Poetry is the journal of a sea animal living on land, wanting to fly in the air.”

-Carl Sandburg

Dibyajyoti Sarma’s Pages from an Unfinished Autobiography is a wistful exploration of journeys through life, its lived realities and desired metaphors. Structured as a series of select journal entries, the poems trace a deep and long history of sorrow—acceptance—sorrow, the mind’s efforts to confront reality, the poet’s anguished heart turning into metaphor the journalist’s experiences. It presents life strung across a wire, taut, waiting to snap, perhaps, but held in place for the moment by the spine of a journal. Lyrical and “seeped in sadness”, the poems thus record stories of moments—probed, prodded, laid out bare—a journey that has to be made even if there is no destination in sight.

“It’s just a place,

Like any other.

It may not be your destination,

But

It certainly is someone else’s.

Take a hike.

Explore the place.

You may start to like it.

There are people who did.

It is after all a destination, like any other.”

The poet is the observer and the observed, the planes of emergence and submergence fluid, continuous, the journey from the outer to the inner ruthless, deliberate, an exorcism of the soul that doesn’t bring relief.

“Oh, how sad, the old beggar

On the roadside

Naked, shivering in the cold

His head between his knees

Like a cloudless piece of sky.

In my warm clothes,

I pitied him, I stood before him

And shedding my clothes one by one

I gave them to him,

My muffler and my torn underwear.

The beggar stood up and

Elaborately put on the clothes

One piece at a time, and finally

The wristwatch. He bowed a little

To thank me, and walked away.

Oh, how sad, I

On the roadside

Naked, shivering in the cold

My head between my knees

Like a cloudless piece of sky.”

(Journal Entry: 78)

The poems negotiate ways and ways, destinations reached and breached, sometimes to find fulfilment, sometimes to forge escape routes, but the journey is unsparing. It snares the traveller, the roads wrap around one another, in the traveller’s “throbbing heart/There lies an impenetrable darkness”. There are no exits; what seem to exist are phantom promises.

“Poems are escape routes

Fire exits

Always there

To make you feel secure.

But when you need them

They bar your entry

With the stubbornness of a six-year-old

Crying for his favourite candy.”

(Journal Entry: 100)

The poet mulls over possibilities, wanders among love and loss, dedicates words to friends and lovers, to those who have inspired and those who have caused despair, deeply aware, all the while, of the pervasive transience of all that takes place; “Finally, nothing remains”. As the refrain resonates across the poems, the tone swings from despair to acceptance to intense yearning, lingering hope:

“He will come.

He won’t.

...

He won’t.

He will.

...

He won’t come.

He will.”

(Journal Entry: 51)

It is in these spaces, in the elision between hope and acceptance, in the repetitive arc of expectation and loss that the poet seems to exist. These intervening spaces spring hope and the joy of anticipation, of finding fulfilment, the intertwining, intense pleasures of loving and leaving, of remembered presence or the expectation of presence.

The poems thus carve a cyclical path, emotions beginning where they ended, the dragon gorging on its tail. The poet travels on, “through time/Through everything for which you/Once wanted to stop”, through the history that engenders them—the day’s experience, the mind’s inquest, its struggle, the meandering between thinking and just living, between distress and hope.

“In short, I’m blind

For a while now.

I’ve removed my eye-balls

And hung them on the gate.

He will walk by this way

Dazzling my sight.”

(Journal Entry: 76)

Elisions also inform the structure of this loose collection of recordings. The journal entries are numbered, though not necessarily in expected succession. What transpires in the blanks? What journeys does the poet undertake, where does the mind wander, how does it come back to the trajectory it has shaped for itself? Intense and repetitive, the general theme of love and yearning is expressed by the poet with sincerity of tone and language that leaves behind melancholy, as also a deeply pervasive mood of knowing that

“Dreams inhabit a different world

Beyond us and surrounding us

We live in glass jars, made of dreams.”

Published on February 04, 2015 23:39

February 3, 2015

Love Is Strange

To the all crazy motherfuckers.

To the all crazy motherfuckers. Alfred Molina and John Lithgow in Ira Sachs’ brilliant and humane Love Is Strange (2014)

Published on February 03, 2015 21:49

“I have missed having your body next to mine too much to ...

“I have missed having your body next to mine too much to have it denied to me for reasons of bad engineering…”

“I have missed having your body next to mine too much to have it denied to me for reasons of bad engineering…” Some love transcends and survives to old age and death. John Lithgow in Ira Sachs’s brilliant and ultimately heartbreaking, Love Is Strange (2014).

Published on February 03, 2015 21:46

“Come closer, I want to kiss you.”I would go running if M...

“Come closer, I want to kiss you.”

“Come closer, I want to kiss you.”I would go running if Mathieu Amalric would stretch his hands and tell me in his French-accented English. In Arnaud Desplechin’s at the same time ambitious and maudlin ‘American’ film about a Blackfoot Native American, the Jimmy P. of the title, and a French doctor, George Devereux, played by Amalric, based on Devereux’s book, Reality and Dream: Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian (1952), Jimmy P. (2013).

Published on February 03, 2015 21:45