Dibyajyoti Sarma's Blog, page 37

July 6, 2015

Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault (French: [miʃɛl fuko]; born Paul-Michel Foucault) (15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, philologist and literary critic. His theories addressed the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. Though often cited as a post-structuralist and postmodernist, Foucault rejected these labels, preferring to present his thought as a critical history of modernity.

Michel Foucault (French: [miʃɛl fuko]; born Paul-Michel Foucault) (15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, philologist and literary critic. His theories addressed the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. Though often cited as a post-structuralist and postmodernist, Foucault rejected these labels, preferring to present his thought as a critical history of modernity. Born in Poitiers, France, into an upper-middle-class family, Foucault was educated at the Lycée Henri-IV and then at the École Normale Supérieure, where he developed an interest in philosophy and came under the influence of his tutors Jean Hyppolite and Louis Althusser. After several years as a cultural diplomat abroad, he returned to France and published his first major book, The History of Madness. After obtaining work between 1960 and 1966 at the University of Clermont-Ferrand, he produced two more significant publications, The Birth of the Clinic and The Order of Things, which displayed his increasing involvement with structuralism, a theoretical movement in social anthropology from which he later distanced himself. These first three histories exemplified a historiographical technique Foucault was developing which he called "archaeology", not to be confused with the academic discipline of archaeology.

From 1966 to 1968, Foucault lectured at the University of Tunis, Tunisia, before returning to France, where he became head of the philosophy department at the new experimental university of Paris VIII. In 1970 he was admitted to the Collège de France, membership of which he retained until his death. He also became active in a number of left-wing groups involved in anti-racist campaigns, anti-human rights abuses movements, and the struggle for penal reform. He went on to publish The Archaeology of Knowledge, Discipline and Punish, and The History of Sexuality. In these books he developed archaeological and genealogical methods which emphasized the role which power plays in the evolution of discourse in society. Foucault died in Paris of neurological problems compounded by HIV/AIDS; he became the first public figure in France to die from the disease, and his partner Daniel Defert founded the AIDES charity in his memory.

More here/

Published on July 06, 2015 23:25

Beyond Black

Hilary Mantel has done something extraordinary. She has taken that ethereal halfway house between heaven and hell, between the living and the dead, and nailed it on the page. She has taken those moments between sleep and waking, when we hardly know who we are, or why, and turned them into a novel that makes the unbelievable believable. She persuades, she convinces, she offers an alternative universe, she uses the extraordinary descriptive skills that are her trademark — Mantel does "seedy" as no one else, except possibly Graham Greene in his early novels, The Confidential Agent and Brighton Rock. She produces characters — some dead, some partly dead, some barely alive but pretending — that are as strong and vivid on the page as if they were living or dying next door — if only you cared to go there. Most don't, next door being a rather nasty and disturbing place. She's witty, ironic, intelligent and, I suspect, haunted. This is a book out of the unconscious, where the best novels come from.

Hilary Mantel has done something extraordinary. She has taken that ethereal halfway house between heaven and hell, between the living and the dead, and nailed it on the page. She has taken those moments between sleep and waking, when we hardly know who we are, or why, and turned them into a novel that makes the unbelievable believable. She persuades, she convinces, she offers an alternative universe, she uses the extraordinary descriptive skills that are her trademark — Mantel does "seedy" as no one else, except possibly Graham Greene in his early novels, The Confidential Agent and Brighton Rock. She produces characters — some dead, some partly dead, some barely alive but pretending — that are as strong and vivid on the page as if they were living or dying next door — if only you cared to go there. Most don't, next door being a rather nasty and disturbing place. She's witty, ironic, intelligent and, I suspect, haunted. This is a book out of the unconscious, where the best novels come from.If, as a reader, you feel briskly and brightly that dead is dead, alive is alive, and anything else is nonsense, this novel is probably not for you. Too weird, you'll say. But they are out there, on the road, the Alisons, the mediums. Thousands turn up to hear her, trust her.

Alison, off to her next gig in London's outer suburbs, the wasteland of people and places, the haunting grounds of the dead: "Travelling: the dank oily days after Christmas. The motorway, its wastes looping London: the margin's scrub grass flaring orange in the lights, and the leaves of the poisoned shrubs striped yellow-green like a cantaloupe melon. Four o'clock: light sinking over the orbital road. Teatime in Enfield, night falling on Potters Bar."

Alison, a size 22 on a good day, is a bridge between the living and the dead. She has inherited "the gift", as others do the gene for playing the piano. Her prostitute mother has a murdered, invisible friend, Gloria. Her grandmother's no better. Sometimes Alison gets it right, sometimes she doesn't, as she confronts her audience in scout halls and spiritualist churches. The dead tell her lies, and are as tricky as the living: channelling makes her ill; she is in constant pain. She frequents the world of psychic fairs, of crystal-gazers and mind readers; she has friends, colleagues, and makes a comfortable living as a "professional". "They don't call you mad if you make a living." A mix of therapist, fraud and saint, she comforts and consoles those whom others disregard — the old, the sick, the lonely, the uneducated and the dim, in whom the energy of life flickers so low they can barely be counted among the living.

The living and the dead demand her ear; difficult to record her life story as her sceptical assistant Collette, hoping to make money from it, demands — there is too much interference, too much clamour and complaint from the other side. Alison to Collette: "Can we switch the tape off now, please? Morris is threatening me. He doesn't like me talking about the early days. He doesn't want it recorded." Morris, the millstone round Alison's neck, is her spirit guide: a vulgar, pimply, smelly, violent and nasty character, whose position of rest is slumped against her bedroom wall, fiddling with his flies. Collette, who lives with Alison, cannot see him, but occasionally detects a kind of sewage whiff in the air and knows he's around. "Other mediums," Alison complains, "have spirit guides with a bit more about them — dignified impassive medicine men or ancient Persian sages — why does she have to have a grizzled grinning apparition in a book-maker's check jacket, and suede shoes with bald toecaps."

More here/

/

HILARY MANTEL'S funny and harrowing new novel is the story of a woman who is coming to terms -- better late than never, as any one of the book's many platitude-dependent characters might say -- with her extremely disturbing past. And I say "coming to terms with" because that, too, is just the sort of comforting, shock-absorbing expression, familiar to viewers of the more earnest and wetly therapeutic daytime talk shows, that Mantel has made it her mission to seek out and destroy. The process undergone in the pages of "Beyond Black" by its fat, middle-aged English heroine, Alison Hart, is self-analysis and memory recovery of almost unimaginable psychic violence -- not the kind of self-actualizing experience Dr. Phil would recommend.

This is more like "The Exorcist," with spinning heads and projectile vomiting and Jesuits hurling themselves through windows.

That's what coming to terms with one's past is, Mantel means to tell us, and she should know, having recently done the deed herself, in a painful, brilliantly prickly memoir called "Giving Up the Ghost."+She may regret not having saved that title for this book, because the heroine of "Beyond Black" is laboring to divest herself of malign spirits who are present in her life in the most immediate and most literal way.+Alison is a professional medium and clairvoyant -- in her preferred terminology, a "Sensitive" -- and depends for her peculiar living on the services of a "spirit guide" named Morris, who is, in death as he was in life, an exceptionally nasty piece of work. He is also a constant reminder of the unspeakable childhood that Alison, for all her extrasensory powers, can recall only dimly.

Morris is the ghost she longs to give up, "this grizzled grinning apparition in a bookmaker's check jacket, and suede shoes with bald toe caps" -- a demon who sees himself as a lovable rogue, a sport, but is in fact about as foul a specimen of humanity, living or dead, as British fiction has conjured up in the past few years. (At least since Ian McEwan cleaned up his act.) And, worse, Morris has mates: a crew of villains whom he has begun to gather around him, from the four corners of the underworld, all of them now converging on the already crowded consciousness of Alison the Sensitive.

It is no coincidence that Morris's horrible party guests start turning up just as Alison has begun to dictate her autobiography to her "sharp, rude, and effective" new assistant, Colette. The "fiends," as Alison calls them, are of course Mantel's metaphor for the awful, toxic stuff that tends to bubble up from the depths of the unconscious when a person tries to write her memoirs. There's a passage early in "Giving Up the Ghost" in which Mantel admits "I hardly know how to write about myself," and briefly resolves to keep it simple, "plain words on plain paper" -- a resolution she sheepishly abandons in the next paragraph. "I stray away from the beaten path of plain words," she writes, "into the meadows of extravagant simile," and in "Beyond Black" she strays yet farther, finding in Alison the most extravagant simile of all. A novelist writing her memoirs, Mantel seems to say, is like a psychic reading her own mind.

More here/

Published on July 06, 2015 23:19

Chocolat

Chocolat is a 1999 novel by Joanne Harris. It tells the story of Vianne Rocher, a young single mother, who arrives in the French village of Lansquenet-sous-Tannes at the beginning of Lent with her six-year-old daughter, Anouk. Vianne opens a chocolate shop, La Céleste Praline, right opposite the village church, and throughout the traditional season of fasting and self-denial, proceeds to gently change the lives of the villagers who visit her chocolaterie with a combination of sympathy, subversion and a little magic.

Chocolat is a 1999 novel by Joanne Harris. It tells the story of Vianne Rocher, a young single mother, who arrives in the French village of Lansquenet-sous-Tannes at the beginning of Lent with her six-year-old daughter, Anouk. Vianne opens a chocolate shop, La Céleste Praline, right opposite the village church, and throughout the traditional season of fasting and self-denial, proceeds to gently change the lives of the villagers who visit her chocolaterie with a combination of sympathy, subversion and a little magic.This scandalizes the parish priest, Francis Reynaud, and his supporters. As tensions run high, the community is increasingly divided. And as Easter approaches, pitting the ritual of the Church against the indulgence of chocolate, Father Reynaud and Vianne Rocher face an inevitable showdown.

Harris has indicated that several of the book's characters were influenced by individuals in her life: Her daughter forms the basis for the young Anouk, including her imaginary rabbit, Pantoufle. Harris' strong-willed and independent great-grandmother influenced her portrayal of both Vianne and the elderly Armande.

A sequel to the novel, The Lollipop Shoes, was released in the UK in 2007; it was released in the US in 2008 under the title The Girl with No Shadow.[2] In 2012, a third chapter in Vianne's story was published, entitled Peaches for Monsieur le Curé (Peaches for Father Francis in the US).

More here/

Published on July 06, 2015 05:30

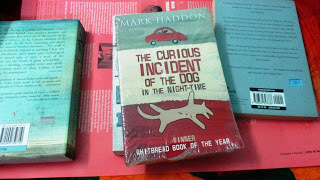

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is a 2003 mystery novel by British writer Mark Haddon. Its title quotes the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes in Arthur Conan Doyle's 1892 short story "Silver Blaze". Haddon and The Curious Incident won the Whitbread Book Awards for Best Novel and Book of the Year, the Commonwealth Writers' Prize for Best First Book, and the Guardian Children's Fiction Prize. As a writer for The Guardian remarked, "Unusually, it was published simultaneously in separate editions for adults and children."

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is a 2003 mystery novel by British writer Mark Haddon. Its title quotes the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes in Arthur Conan Doyle's 1892 short story "Silver Blaze". Haddon and The Curious Incident won the Whitbread Book Awards for Best Novel and Book of the Year, the Commonwealth Writers' Prize for Best First Book, and the Guardian Children's Fiction Prize. As a writer for The Guardian remarked, "Unusually, it was published simultaneously in separate editions for adults and children."The novel is narrated in the first-person perspective by Christopher John Francis Boone, a 15-year-old boy who describes himself as "a mathematician with some behavioural difficulties" living in Swindon, Wiltshire. Although Christopher's condition is not stated, the book's blurb refers to Asperger syndrome, high-functioning autism, or savant syndrome. In July 2009, Haddon wrote on his blog that "Curious Incident is not a book about Asperger's....if anything it's a novel about difference, about being an outsider, about seeing the world in a surprising and revealing way. The book is not specifically about any specific disorder," and that he, Haddon, is not an expert on autism spectrum disorder or Asperger syndrome.

The book is dedicated to Sos Eltis, Haddon's wife, with thanks to Kathryn Heyman, Clare Alexander, Kate Shaw and Dave Cohen.

The book is notable for using prime numbers to number the chapters, rather than the conventional successive cardinal numbers.

More here/

Published on July 06, 2015 05:26

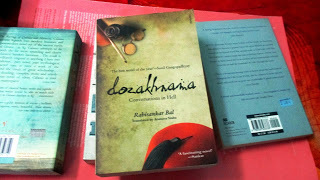

Dozakhnama

I don’t know what got me attracted to this book. Perhaps it was the praise I heard from one of my friends, who said in her review: “Have you ever been burnt by a book? Been trapped between its pages, gasping for air? Have you felt that if you read any more you’d die; but if you didn’t read, you’d die anyway? If you’ve not had the pleasure of such a pain, read Dozakhnama.” Urmi, I can’t help but agree with that assessment. Maybe even the tagline “Conversations in hell” was also something that piqued my interest, and I took up this book as one of my reads for this year.

I don’t know what got me attracted to this book. Perhaps it was the praise I heard from one of my friends, who said in her review: “Have you ever been burnt by a book? Been trapped between its pages, gasping for air? Have you felt that if you read any more you’d die; but if you didn’t read, you’d die anyway? If you’ve not had the pleasure of such a pain, read Dozakhnama.” Urmi, I can’t help but agree with that assessment. Maybe even the tagline “Conversations in hell” was also something that piqued my interest, and I took up this book as one of my reads for this year.This is literary fiction, and a translated one at that. Originally written in Bengali by Rabisankar Bal, and now translated by Arunava Sinha, this book is evocative in its poetry. This book is the conversation between two great poets, Saadat Hassan Manto and Mirza Ghalib and the conversation happens after their death, from their graves, and the story itself is the supposed translation of one of Manto’s unpublished novels.

If you are fond of only stories that move very quickly, or read just for fun, perhaps this book might not be that appealing. If you are willing to let the words seep into you and make you wonder, then this book would do that. When I first got the book, I opened to a random page and found a small verse, that translated to this:

I shall not give up on my desire if it remains unfulfilled

My heart will either reach my lover, or leave my body

When I am dead, dig up my grave, you’ll find my shroud

Covered in smoke, for the fire is still burning inside

That verse pushed me in to the book. For this verse can even be indicative of the passion of a writer as it does to a lover here. As I read on, I found many such verses, couplets and poetry that I could understand as a poet and a writer. Another couplet translates to say:

Like a kite, my heart had once

Yearned to fly to freedom

More here/

/

Dozakhnama doesn’t start in Hell. Rather, it opens with a journalist who has discovered an unpublished manuscript, supposedly written by the late Punjabi author Saadat Hasan Manto. The date on the manuscript says it was written the day of Manto’s death—a novel written from the grave. The journalist undertakes a translation, and from there we descend into the world of ghosts and ghostwriters within the discovered manuscript.

The novel-within-a-novel is an imagined conversation between Manto and the 19th-century poet, Mirza Ghalib. They do indeed speak from the grave: two writers in Hell, spinning tales. Manto and Ghalib alternate narration, each telling his life story—his relationships with writing, with women, with addiction, and with the turbulent events that shaped India in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Rabisankar Bal, who has written over fifteen novels, originally published Dozakhnama in Bengali in 2010. Now, Arunava Sinha has given us the first English translation. Violence, self-destruction, and religious yearning unspool slowly in this complex, often meandering novel. The author reveals slices of Indian and Pakistani history through the voices of its literary giants. While at times slow, Dozakhnama rewards the patient reader with beautiful sentences and a narrative structure that enacts the value of storytelling.

Dozakhnama is a story wrapped in stories, a series of fictions. The two characters spin tales to each other, and their tales spin further tales, taking the reader farther and farther from the main plot. Various dastangos (storytellers) appear throughout the novel, as do mystics and poets, each with a new unraveling of yarns.

If this all seems complicated, it’s supposed to be. Shifting identity is one of the novel’s themes. The stories of Dozakhnama do not belong to individuals, but to a community. In the form of ghazals and dastans (stories), heritage passes as rendered and re-rendered oral history. For Bal, authorship is an act of disappearance.

More here/

/

When Christopher Marlowe's Dr. Faustus makes a pact with Mephistopheles (spirit of the Devil) and willingly trades his soul in search of supreme knowledge and power that extend beyond the world of mortality; he does not realise he is walking the road to hell. A German scholar who believed he has reached the end of every subject, Faustus is taken over by an overreaching ambition that ultimately drives him to eternal damnation. But why this unrelenting quest for knowledge had to meet such a punishment or was it Faustus' greed and hubris that consumed his all?

Unlike Faustus who designed his own route to hell and was silenced forever, there were two writers (born in two different centuries) who revisited their lives and found their lost voices from within the contours of their respective graves. When two literary giants- Mirza Ghalib, the quintessential classical Urdu and Persian poet of the Mughal era and Saadat Hasan Manto, a controversial short story writer of the 20th Century start a conversation, what follows is an unfolding of a history of a country that has withstood all seasons of change, years of colonial rule, partition and war, several months of captivity and countless days of poverty.

Rabisankar Bal's novel 'Dozakhnama: Conversations in Hell' re-imagines the 'dozakh' (hell) not as a prison cell everyone dreads to live in but a liberating space that allows an undeterred flow of free thoughts sans fear of censorship or condemnation.

An abandoned manuscript, an untold story

In Lucknow to research on courtesans (tawaifs) of the city, a journalist (also the narrator of the story) meets Farid mian, a once upon a time writer and now a 'madman' chased by 'shadows of people' talking to him. Farid mian hands over an unpublished manuscript he had guarded for years to the journalist, requesting him to get it published and, thus, relieve him of the story, a burden he no longer can bear. The novel, as Farid claims was written by Manto on Mirza Ghalib, "Manto sahib used to dream of writing a novel about Mirza Ghalib." The manuscript is written in Urdu and the narrator, to whom the script is not known, admires the calligraphy of the written word for long as he carefully turns its crumbling pages. He returns to Calcutta with the manuscript and arranges for an Urdu teacher who first agrees to teach him the language but later, on his suggestion, reads out the story to him while he writes it down like a dutiful scribe. The veracity of the novel stands questioned in the introduction chapter itself that ends with Manto's signature dated January 18, 1955; the very date Manto died on. Names do not really matter; stories are what travel for ages across generations, and with this spirit in mind, the reader is slowly drawn into the wonderfully woven world of the two most loved writers.

More here/

/

Exhumed from dust, Saadat Hasan Manto's unpublished novel surfaces in Lucknow. Not conversant in Urdu, the tale-teller of the story gets in touch with Tabassum, a lady knowing the language in order to translate the novel from Urdu to Bengali. As Tabassum makes the author understand the narrative, the story gradually unfolds. In Dozakhnama: Conversations in Hell, Manto and Mirza Ghalib converse from their respective graves that are apart both in distance and time, entwining their lives in shared dreams. The result is an intellectual journey that takes us into the people and events that shape us as a culture.

Originally written in Bengali by Rabisankar Bal and translated into English by Arunava Sinha, Dozakhnama is not a rigid Historical Fiction. In essence it is a meandering tale in which two of the great literary stalwarts who are separated from each other by almost a century and by a distance of that between Delhi and Lahore, take turns to tell the story of their lives and the time periods they lived in. The author has tremendous command over the story line and these conversations in hell never appear to detach from the flow. It is hard to realize that this is actually a novel inside a novel and the reader is tempted to follow an actual conversation between Manto and Ghalib from their graves and get a fantastic view of the socio political landscape of the time period in Indian History.

More here/

/

There are a few books that you just don’t want to finish in a single seating. You want to devour them slowly and feel the intensity of words and emotions to your utmost satisfaction. Dozakhnama by Rabi Sankar Bal is originally written in Bengali and one of the best translators of the country Arunava Sinha has translated this mammoth book in English. I got a chance to meet him at one of the bloggers meet organised by Random House India and I came to know some amazing facts about the book and translations.

Dozakhnama, Conversations in Hell is a masterpiece. In this book Ghalib and Manto, THE MAESTROS are conversing with each other from their respective graves. It is a Dastan and a reader would never want to get done with. Both discussing their lives, their pains, joys, hardships that life gave them and still they kept going strong. Lives of both Ghalib and Manto are woven in this book in such a way that you just cant get over with it. The book has 45 chapters and it took me more than a month to finish this one. I used to read 1 chapter daily religiously. I wanted to read more each time but had to put down the book because Dozakhnama is actually a very heavy read.

More here/ /

Published on July 06, 2015 05:24

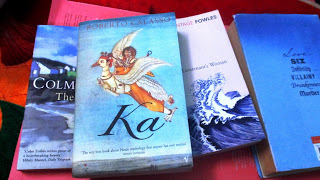

Ka

t was as if everybody were suddenly tired of doing things that had meaning. They wanted to sit down, in the grass or around a heap of smoldering logs, and listen to stories.'' Roberto Calasso's gloss on the epic intricacies of the Mahabharata, the longest story in the world, might also stand as a caption to his own new book, sleepless in its storytelling. But we should not be disarmed, for the book, ingeniously translated from the Italian by Tim Parks, is equally quick with meanings.

t was as if everybody were suddenly tired of doing things that had meaning. They wanted to sit down, in the grass or around a heap of smoldering logs, and listen to stories.'' Roberto Calasso's gloss on the epic intricacies of the Mahabharata, the longest story in the world, might also stand as a caption to his own new book, sleepless in its storytelling. But we should not be disarmed, for the book, ingeniously translated from the Italian by Tim Parks, is equally quick with meanings.The third in a planned five-volume work, ''Ka'' -- which the publisher describes as ''stories of the mind and gods of India'' -- follows the high torsion of ''The Ruin of Kasch'' (1996), which evoked the emergence of the modern from the collapse of the past, and the more languorous seductions of ''The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony'' (1994), which subsumed the whole of Greek mythology in a single meditation.

To read ''Ka'' is to experience a giddy invasion of stories -- brilliant, enigmatic, troubling, outrageous, erotic, beautiful. Yet ''Ka,'' like the two previous books, is not a novel. Calasso's form-defying works plot ideas, not character. A writer with philosophical tastes, he thinks in stories rather than arguments or syllogisms. The two epigraphs to ''Ka'' announce this style: Spinoza's remark that ideas are only narratives or mental figures of the real world and, from the Yogavasistha, a definition of the world as being ''like the impression left by the telling of a story.''

''Ka'' is the emotional and philosophical nub of Calasso's five-volume project. His acutely nominalist temperament finds its ideal home in the stories of India, especially those early stories of the Aryans, which affirm always the power and sovereignty of mind. As Atri, one of the seven rsis, or seers, of the Aryas (the people that migrated from central Asia to India and became the upper castes there), says, ''Every true philosopher thinks but one thought; the same can be said of a civilization.'' The one crystallizing insight of the Aryan intellect, as Calasso sees it, is that the existent world ''only exists if consciousness perceives it as existing. And if a consciousness perceives it, within that consciousness there must be another consciousness that perceives the consciousness that perceives.''

It is to this vertigo-inducing thought that the stories of ''Ka'' constantly return. The book opens and closes with a flight by Garuda, the great eagle best known as the steed of Vishnu but here cast in a central role. At the beginning and at the end, he reads the Rig-Veda, intrigued by the incantatory question of Hymn 121 of the 10th book: ''Who (Ka) is the god to whom we should offer our sacrifice?'' Like Garuda's inky feathers, this question rustles through the book. The answer (if a reply so mysterious may be called that) is Prajapati: the ''nameless and shapeless'' one, whose secret name is itself Ka, or ''who.'' He precedes even Brahma, the creator and first god of the later Hindu triad of deities (the others being Siva and Vishnu). Alone, Prajapati is without identity: ''He didn't even know whether he existed or not.'' In fact, Prajapati is nothing less than mind, manas; and, desiring to know himself, to gain self-consciousness, he creates the world, bringing forth beings able to perceive one another.

In the span between Garuda's taking wing twice, the stories of ''Ka'' enact the emergence of consciousness, always split between the self and the I, atman and aham. As Garuda perches on the immense tree of life, puzzling over the identity of Ka, ''the very syllable from which everything had issued forth,'' the stories stream out.

Beginning with the Rig-Veda, the book navigates the narrative ocean of the Brahmanas, the Upanishads, the Mahabharata and the Puranas, as well as stories of the Buddha. The stories become more orotund as we move ''from the allusive cipher of the Rig-Veda and the abrupt, broken narratives of the Brahmanas . . . to the ruthless redundance of the Puranas.'' And, in the vast wake of stories that succeed the Rig-Veda, the names of the gods change, as do the literary genres and the demands on the listener: ''There was a time when he'd been obliged to solve abrupt enigmas, or find his head bursting. Now he could heap up rewards merely by listening to the stories as they proliferated. The shift had to do with a growing weariness: the era of the bhakti had begun, the era of obscure and pervasive devotion.''

More here/

/

In Ka Roberto Calasso has taken the sprawling body of classical Sanskrit literature and synthesized it into a kind of novel. Each of its fourteen chapters foregrounds a particular figure, such as Prajapati, Shiva, Krishna, or the Buddha, or a story such as the Mahabharata. And each chapter is made up of vignettes ranging from short paragraphs to several pages in length, which link together to form a coherent stream but to an extent can stand alone. The chapters are ordered — proceeding from the creation of the world to the Buddha, framed by Garuda and Ka — but the weave is loose and Ka doesn't have to be read cover-to-cover to be appreciated.

Though the individual passages are often dazzling little gems in their own right, the way they are worked together into a larger mosaic is just as impressive. There are sections of quite fast-moving narrative:

Then Garuda looked around. Opposite Vinata, likewise sitting on a stone, he saw another woman, exactly like his mother. But a black bandage covered one eye. And she too seemed absorbed in contemplation. On the ground before her, Garuda saw, lay a great tangle, slowly heaving and squirming. His perfect eye focused, to understand. They were snakes. Black snakes, knotted, separate, coiled, uncoiled. A moment later Garuda could make out a thousand snakes' eyes, coldly watching him. From behind came a voice: "They are your cousins. And that woman is my sister, Kadru. We are their slaves." These were the first words his mother spoke to him.

More here/

Published on July 06, 2015 04:35

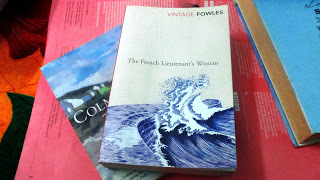

The French Lieutenant's Woman

The French Lieutenant's Woman is a 1969 postmodern historical fiction novel by John Fowles. It was his third published novel, after The Collector (1963) and The Magus (1965). The novel explores the fraught relationship of gentleman and amateur naturalist, Charles Smithson, and the former governess and independent woman, Sarah Woodruff, with whom he falls in love. The novel builds on Fowles' authority in Victorian literature, both following and critiquing many of the conventions of period novels.

The French Lieutenant's Woman is a 1969 postmodern historical fiction novel by John Fowles. It was his third published novel, after The Collector (1963) and The Magus (1965). The novel explores the fraught relationship of gentleman and amateur naturalist, Charles Smithson, and the former governess and independent woman, Sarah Woodruff, with whom he falls in love. The novel builds on Fowles' authority in Victorian literature, both following and critiquing many of the conventions of period novels.Following publication, the library magazine American Libraries, described the novel as one of the "Notable Books of 1969". Subsequent to its initial popularity, publishers produced numerous editions and translated the novel into many languages; soon after the initial publication, the novel was also treated extensively by scholars. The novel remains popular, figuring in both public and academic conversations. In 2005, TIME magazine chose the novel as one of the 100 best English-language novels published between 1923 and 2005.

Part of the novel's reputation is based on its expression of postmodern literary concerns through thematic focus on metafiction, historiography, metahistory, marxist criticism and feminism. Stylistically and thematically, Linda Hutcheon describes the novel as an exemplar of a particular postmodern genre: "historiographic metafiction." Because of the contrast between the independent Sarah Woodruff and the more stereotypical male characters, the novel often receives attention for its treatment of gender issues. However, despite claims by Fowles that it is a feminist novel, critics have debated whether it offers a sufficiently transformative perspective on women.

Following popular success, the novel created a larger legacy: the novel has had numerous responses by academics and other writers, such as A.S. Byatt, and through adaptation as film and dramatic play. In 1981, the novel was adapted as a film of the same name with script by the playwright Harold Pinter, directed by Karel Reisz and starring Meryl Streep and Jeremy Irons. The film received considerable critical acclaim and awards, including several BAFTAs and Golden Globes. The novel was also adapted and produced as a British play in 2006.

More here/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Fre...

Published on July 06, 2015 04:09

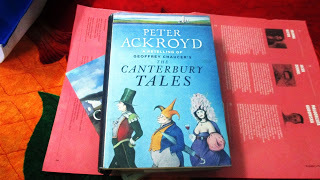

The CanterburyTales by Peter Ackroyd

Though many of us (Peter Ackroyd included) greatly would prefer common readers to learn just enough Middle English to begin enjoying Chaucer’s poetry in the original, that evades the way things are and the way they are going to be. Retelling Chaucer in our contemporary prose necessarily is a great loss, yet so rich is Chaucer that enormous value remains in Ackroyd’s robust versions of “The Canterbury Tales.”

Though many of us (Peter Ackroyd included) greatly would prefer common readers to learn just enough Middle English to begin enjoying Chaucer’s poetry in the original, that evades the way things are and the way they are going to be. Retelling Chaucer in our contemporary prose necessarily is a great loss, yet so rich is Chaucer that enormous value remains in Ackroyd’s robust versions of “The Canterbury Tales.”/

Chaucer’s England was violent: usurpations, civil war and rape were prevalent. He himself had to make a legal settlement for a rape he evidently committed, and he suffered the experience of seeing friends and associates, with whom he had served Richard II, beheaded while he was spared.

As a poet, he clearly had a sense of his magnitude, though his pervasive irony masks it. French was still the language of the court, and Chaucer had chosen to write in the English vernacular. Much of his work is magnificent translation, and I think he would approve, however ironically, Ackroyd’s Chaucerian translation.

Ackroyd is a fiercely prolific novelist, biographer, general person of letters, sometimes reminding me of the equally industrious and similarly brilliant Anthony Burgess, whom I continue to miss personally.

Burgess, though, was at his best in some of his novels, particularly in his Joycean fiction about Shakespeare, “Nothing Like the Sun.” Ackroyd’s novels hold me, particularly his outrageous “Milton in America,” but his best work is in his marvelous cultural visions: “Albion,” “London,” “Thames.” I say “visions” because they convey a comprehensive and frequently dark sense of the English character and its vagaries, including sudden excursions into brutality and lawlessness. That darkly ironic sense is profoundly Chaucerian and suits the poet’s major work, the unfinished yet aesthetically complete “Canterbury Tales,” upon which he continued to work until his death at around 57. He contrasts in this with Shakespeare, who died at 52 and chose to write nothing during his three final years, while retired at Stratford-on-Avon.

Shakespeare’s greatest contemporary, the epic poet Edmund Spenser, derived directly from Chaucer, whom he praised as the “well of English undefiled.” That prompted the 18th-century poet-critic John Dryden to term Chaucer “a perpetual fountain of good sense.” Ackroyd’s Chaucer is a personified London and a humanized Thames, incessantly vital and comprehending everything it flows past.

Like Shakespeare’s plays, “The Canterbury Tales” convey a strong impression of the author’s detachment from his own creation. Chaucer the Pilgrim, a character in the “Tales,” is partly a parody of Dante the Pilgrim in the “Commedia” and partly an anticipation of Jonathan Swift’s Lemuel Gulliver and the Tale-Teller in “A Tale of a Tub.” As pilgrim, Chaucer professes admiration for every scoundrel he gathers together in his company of 28 wayfarers en route to Canterbury. Ackroyd catches the mode in which the pilgrimage is the 14th-century version of our West Indian cruises, erotic and recreational “wanderings by the way.”

More here.

Published on July 06, 2015 03:49

July 3, 2015

From “A Dream Book”By David HarsentDeep reaches of sleep ...

From “A Dream Book”

By David Harsent

Deep reaches of sleep until the unforeseen

moment, like fugue, like petit mal, some kind of sign,

a touch from a joker’s finger, to let him know what’s right,

what’s wrong with the dream-within-a-dream. A sudden, slight

shift in the order of things and all the past undone.

He left what was left of himself in her care that night.

•

They went to the river and dropped their clothes on the bank.

She struck out. He followed in the long, slow vee of her wake.

She could sound and surface, bringing back with her what

other lovers had dumped: hotel bill, gimcrack ring, a four-square shot

from the photo booth. Later, they dipped their bottles and drank.

She looked at him and laughed. “You think you’re safe? You’re not.”

•

In this, her fool is deaf and dumb and twirling a pink parasol. In this

he’s doing a chicken dance. He turns away and puckers up for a kiss.

He’s their stalker, familiar, spy, his slippy grin is all

lipstick and green teeth. Words to the wise, or coffin-laugh, or catcall.

In this, he watches from cover, maestro of the deadfall.

He goose-steps them out of the tunnel of love and into the house of glass.

By David Harsent

Deep reaches of sleep until the unforeseen

moment, like fugue, like petit mal, some kind of sign,

a touch from a joker’s finger, to let him know what’s right,

what’s wrong with the dream-within-a-dream. A sudden, slight

shift in the order of things and all the past undone.

He left what was left of himself in her care that night.

•

They went to the river and dropped their clothes on the bank.

She struck out. He followed in the long, slow vee of her wake.

She could sound and surface, bringing back with her what

other lovers had dumped: hotel bill, gimcrack ring, a four-square shot

from the photo booth. Later, they dipped their bottles and drank.

She looked at him and laughed. “You think you’re safe? You’re not.”

•

In this, her fool is deaf and dumb and twirling a pink parasol. In this

he’s doing a chicken dance. He turns away and puckers up for a kiss.

He’s their stalker, familiar, spy, his slippy grin is all

lipstick and green teeth. Words to the wise, or coffin-laugh, or catcall.

In this, he watches from cover, maestro of the deadfall.

He goose-steps them out of the tunnel of love and into the house of glass.

Published on July 03, 2015 06:28

The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar

Published on July 03, 2015 05:38