Dibyajyoti Sarma's Blog, page 33

October 21, 2015

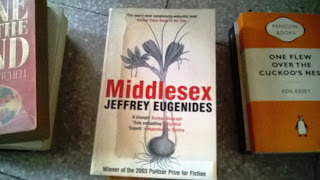

Middlesex

Gore Vidal once joked that the advantage of bisexuality was that it doubled your chances of a date on a Saturday night. By extension, hermaphrodites could be said to have the third option of a good night in on their own. But in this epic novel narrated by an American born with twin-set genitals, Jeffrey Eugenides silences such cheap jokes with a rich comedy of his own.

Gore Vidal once joked that the advantage of bisexuality was that it doubled your chances of a date on a Saturday night. By extension, hermaphrodites could be said to have the third option of a good night in on their own. But in this epic novel narrated by an American born with twin-set genitals, Jeffrey Eugenides silences such cheap jokes with a rich comedy of his own.Because the condition the writer calls "middlesex" is caused by a recessive gene (one usually negated by the other parent's DNA), it tends to appear only once in several generations. The same was beginning to seem regrettably true of books by Eugenides.

This second novel follows almost a decade after his astonishing debut, The Virgin Suicides, in which five daughters from a very correct American family take their own lives in succession. Intriguingly, the only equally praised book-rookie of the same period - Donna Tartt, with The Secret History - has also waited until late this year to get to second base. In American letters, the theme of this fall is the attempt to fulfil high promise.

More here/

/

Those Greeks and their hermaphrodites! Teiresias, the seer who futilely haunts so many Greek tragedies, was one. Having enjoyed the special privilege of living as both a male and a female, he was asked by the gods to settle an argument about which of the two sexes had more pleasure from lovemaking; on asserting that the female did, he was struck blind by prudish Hera—but given the gift of prophecy by Zeus as a compensation. The minor deity Hermaphroditus, of course, was another, appearing in religion (there is evidence of dedications to the god as early as the third century BC in Attica), in literature (Ovid, in the fourth book of Metamorphoses, elaborates the mythic narrative in which this son of Hermes and Aphrodite was joined in one body with the nymph Salmacis), and in art, where the opportunities for imaginative representations of this strange creature proved irresistible, predictably enough, to Hellenistic sculptors, with their penchant for the extreme. The most famous of these sculpted hermaphrodites is a Greek one from about 150 BC, which survives in Roman copies such as the one to be found in the “Hermaphrodite Room” in the Uffizi. At first glance, the figure seems to be that of a sleeping woman. She lies face down, and is quite voluptuous: her breasts, pressed against the couch on which she reclines, are full, as are her hips. Her hair is carefully, fashionably coiffed. On closer inspection, however, it becomes clear that this is no ordinary female. For there, peeking out of the voluminous folds of her gown, is a penis, as modest and perfectly formed as any of the unassuming members familiar from countless classical nudes. Male nudes, that is.

To this catalog we may now add another Greek, Calliope Stephanides, the heroine—and later the hero (“Cal”)—of Jeffrey Eugenides’s second novel, which is slyly entitled Middlesex. (The title ostensibly refers to the name of the street in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, where much of the novel is set.) For adorable little Callie turns out, by the novel’s end, to be a boy—one who suffers from a rare genetic disorder that causes a type of male pseudo-hermaphroditism: although chromosomally male (she has both an X and a Y), she has no real penis, but instead a kind of extended clitoris which she will refer to as “the crocus”; she has testes, but they remain undescended. As a result of this she is misidentified at birth as being a girl and is raised as a girl by her amusingly neurotic, upper-middle-class Greek-American parents. Until puberty, that is, when her male hormones kick in and it becomes increasingly evident that she is no ordinary female. (For one thing, she doesn’t menstruate, although she tries mightily to fake it: “I did cramps the way Meryl Streep does accents.”) It is only after a road accident lands her in an emergency room that Callie and her bewildered family realize how extraordinary she really is. Middlesex, then, is a Bildungsroman with a rather big twist: the Bildung it describes turns out to be the wrong one—a false start.

More here/

/

EVEN before she's born, Calliope Stephanides's gender is up for debate. Her parents, Milton and Tessie Stephanides of Detroit, want a girl, and a bachelor uncle convinces Milton, ostensibly on the authority of an article in Scientific American magazine, that if the couple have ''sexual congress'' 24 hours prior to ovulation ''the swift male sperm would rush in and die off. The female sperm, sluggish but more reliable, would arrive just as the egg dropped.'' Tessie complies, despite her worries that ''to tamper with something as mysterious and miraculous as the birth of a child was an act of hubris.'' Once Tessie is pregnant, Milton's mother, Desdemona -- a refugee with her husband, Lefty, from a Greek village on the slopes of Mount Olympus -- dangles a silver spoon tied to a string over the belly of her daughter-in-law and pronounces the child a boy. Her son storms in to protest the divination; the baby is a girl, he insists. ''It's science, Ma.''

They're both right, after a fashion. Callie will spend the 1960's and early 70's, the first years of her life, as the relatively unremarkable daughter of an entrepreneurial Greek-American family, only to discover at 14, in the office of a Manhattan physician, that she is a hermaphrodite -- or, more precisely, a pseudohermaphrodite, a sufferer of 5-alpha-reductase deficiency syndrome. ''To the extent that fetal hormones affect brain chemistry and histology, I've got a male brain,'' explains Cal, the man Callie decides to become after she learns the truth and the narrator of ''Middlesex,'' Jeffrey Eugenides's expansive and radiantly generous second novel. ''But I was raised as a girl.''

Eugenides's first novel, ''The Virgin Suicides'' (1993), was a dreamy, slender book about the gulf in understanding between the adolescent boys in a Michigan suburb and the five daughters of a strict Roman Catholic couple living in their neighborhood. The boys fill that gulf with romantic obsession, a beast that thrives in a vacuum, and the girls, stricken with a fatal loneliness, die by their own hands like a bevy of unlucky fairy tale princesses. ''Middlesex'' may be an entirely different sort of book -- it's longer, more discursive and funnier, for a start -- but it's equally preoccupied with rifts. There's the gap between male and female, obviously, but also between Greek and WASP, black and white, the old world and the new, the silver spoon and the sluggish sperm. Finally, there is the tug of war between destiny and free will -- an age-old concern of Greek storytellers, as every college freshman learns, reborn in the theories advanced by evolutionary psychology.

Evolutionary psychology, at least in its popular incarnation -- which seems to get more popular every day -- keeps chipping away at the garden-variety humanism espoused by most novelists. That's why it's surprising so few of them (at least within the genre of literary fiction) have bothered to take notice of it. Viewed through a sociobiological lens, infidelity, the novel's favorite meat, is transformed from the stuff of betrayal and moral failing to the mere playing out of a Darwinian reproductive imperative; despair springs from an inherited defect in the regulation of neurochemicals, not from an existential apprehension of the absurdity of the human condition. The tangled parks and gardens that have long been the novelist's stamping grounds are being bulldozed to make way for sleek, sterile industrial complexes where, in cataloging each molecule in the human genome, scientists may ultimately be able to tell us which gene caused Anna Karenina to cheat and gave Oliver Twist the nerve to ask for more gruel.

More here/

Published on October 21, 2015 04:05

September 24, 2015

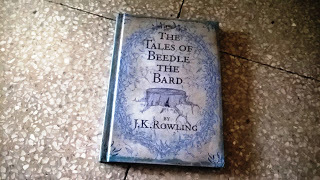

The Tales of Beedle the Bard

The Tales of Beedle the Bard is a book of children's stories by British author J. K. Rowling. It is a storybook of the same name mentioned in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the last book of the Harry Potter series.

The Tales of Beedle the Bard is a book of children's stories by British author J. K. Rowling. It is a storybook of the same name mentioned in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the last book of the Harry Potter series.The book was originally produced in a limited edition of only seven copies, each handwritten and illustrated by J. K. Rowling. One of them was offered for auction through Sotheby's in late 2007 and was expected to sell for £50,000 (US$77,000, €69,000); ultimately it was bought for £1.95 million ($3 million, €2.7 million) by Amazon, making the selling price the highest achieved at auction for a modern literary manuscript. The money earned at the auction of the book was donated to The Children's Voice charity campaign.

The book was published for the general public on 4 December 2008, with the proceeds going to the Children's High Level Group.

More here/

/

JK Rowling inserted a kind of fairy tale into Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the seventh and last Harry Potter tome. In his will, Professor Dumbledore leaves Hermione Granger his copy of The Tales of Beedle the Bard, a collection of children's stories, and she later reads one out. In "The Tale of the Three Brothers", the brothers meet Death and win from him an Elder Wand, a Resurrection Stone and a Cloak of Invisibility. The greedy brothers who win the Wand and the Stone perish by them; the humble brother with the cloak lives a long life protected by it from Death, until in old age he voluntarily relinquishes it. These magical objects are the "Deathly Hallows" of the book's title. The story concerns the dangerous desire to vanquish death, a preoccupation in the book.

Now Rowling has given us Dumbledore's collection, adorned with her own drawings and sold in aid of the children's charity that she set up with politician Emma Nicholson. It is a thin volume, with just four more brief tales added to the reprinted "Three Brothers", and bulked out with Dumbledore's "notes". Rowling is beyond needing to manufacture spin-offs, and the collection probably did begin, as she says, as a jeu d'esprit. Yet the fairy story is a tricky form, and it is not clear that Rowling's inventiveness and humour are suited to the genre.

One problem is magic. Some of the most haunting stories of the Grimms or Hans Christian Andersen get their force from the eruption of the supernatural into the ordinary world. The ending to a fairy tale characteristically involves the end of magic: a curse is lifted, a spell is broken. Rowling explains that in her tales the heroes and heroines are familiar with magic already. In the first tale, "The Wizard and the Hopping Pot", a young wizard inherits a magic cooking pot from his father and has to learn to use it for the good of others. In a traditional tale, the son would be a selfish boy who was being admonished from another world. In Rowling's version, he is more like a geek having trouble with a new machine.

A second story, "The Fountain of Fair Fortune", features a twist that many will recognise from "The Emperor's New Clothes": its characters believe their lives are being transformed by magic when in fact the fountain that brings happiness to each of them "carried no enchantment at all". Yet here too the spin is taken off the narrative by characters who are themselves capable of magic. A love-lorn witch uses her wand to draw from her mind all memories of the lover who has deserted her: a nice psychotherapeutic trick if you can do it.

More here/

Published on September 24, 2015 05:30

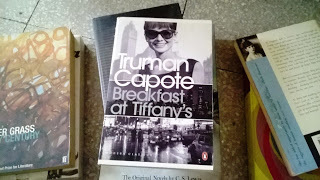

Breakfast at Tiffany's

Breakfast at Tiffany's is a novella by Truman Capote published in 1958. The main character, Holly Golightly, is one of Capote's best-known creations.

Breakfast at Tiffany's is a novella by Truman Capote published in 1958. The main character, Holly Golightly, is one of Capote's best-known creations.In autumn 1943, the unnamed narrator becomes friends with Holly Golightly, who calls him "Fred," after her older brother. The two are both tenants in a brownstone apartment in Manhattan's Upper East Side. Holly (age 18–19) is a country girl turned New York café society girl. As such, she has no job and lives by socializing with wealthy men, who take her to clubs and restaurants, and give her money and expensive presents; she hopes to marry one of them. According to Capote, Golightly is not a prostitute but an "American geisha."

Holly likes to shock people with carefully selected tidbits from her personal life or her outspoken viewpoints on various topics. Over the course of a year, she slowly reveals herself to the narrator, who finds himself fascinated by her curious lifestyle.

More here/

/

There is something wistful about this novel. It makes me feel like Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a place I’ve been to before. It reminds me of a time in life when parties happened at all hours, when people came and went, where the normal rules of life were thrown out the window and where intense relationships happen and then quickly disappear leaving that mysterious footprint of “whatever happened to…?”, knowing that that person irrevocably changed the DNA of your own life, making it seem much grayer, so much less, without them.

That is the feeling I got when I read Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Of course, Audrey Hepburn brought Holly Golightly to life in a light, glamourous insouciant version that the world fell in love with. The real Holly, Truman Capote’s Holly, is in fact much darker, a much more layered person. When she and her brother are orphaned at a young age and she marries at 14 she runs away from this life and the person she is. She is a young, beautiful girl who reinvents herself as a highly sought after social escort who lives life as if each moment were a holiday. Holiday Golightly – Traveling is what’s written on her business cards.

The story is told from the point of view of “Fred”, a struggling young writer, who gets to know Holly when she moves into an apartment in his old brownstone in New York during the second world war. He first meets her when she appears on his fire escape but long before that, he heard the music, the parties and the voices of an endless stream of middle-aged men who came and went from her flat.

Over the course of the year and half that he knows her, Fred, a name that she gives him because he reminds her of her brother, is pulled into the slipstream of Holly Golightly, who entertains Hollywood directors, wealthy gentleman she dines with nightly and who dreams of marrying rich. Her solace, when she seeks it, is at Tiffany’s which offers an almost realized form of the life she longs for.

Her invented self is so large that the distance between it and reality is far enough that you fear that she’ll never find that centre that everyone needs to understand where they belong. “It could go on forever.” she says “Not knowing what’s yours until you’ve thrown it away.” There are only a few moments in the book where the rawness and vulnerability of her true self is momentarily revealed and it grabs your heart in the same way as when you see a wounded animal.

More here/

Published on September 24, 2015 05:28

The Assassin

Published on September 24, 2015 05:22

Avengers: Age of Ultron

Published on September 24, 2015 05:21

The Edge of Tomorrow

Published on September 24, 2015 05:20

Boys in the Band

Published on September 24, 2015 05:19

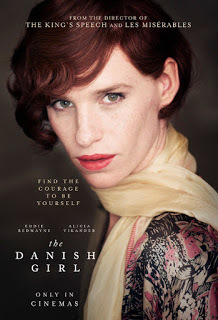

The Danish Girl

Published on September 24, 2015 05:17

August 31, 2015

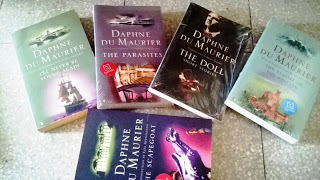

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning DBE (/ˈdæfni duː ˈm...

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning DBE (/ˈdæfni duː ˈmɒri.eɪ/; 13 May 1907 – 19 April 1989) was a British author and playwright.

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning DBE (/ˈdæfni duː ˈmɒri.eɪ/; 13 May 1907 – 19 April 1989) was a British author and playwright.Many of her works have been adapted into films, including the novels Rebecca (the film adaptation of which won the Best Picture Oscar in 1941) and Jamaica Inn, and the short stories The Birds and Don't Look Now. The first three film adaptations were directed by Alfred Hitchcock and the last by Nicolas Roeg.

Her grandfather was the artist and writer George du Maurier and her father the actor Gerald du Maurier. Her elder sister Angela also became a writer, and her younger sister Jeanne was a painter.

/

Works/

Fiction/

The Loving Spirit (1931)

I'll Never Be Young Again (1932)

The Progress of Julius (1933) (later re-published as Julius)

Jamaica Inn (1936)

Rebecca (1938)

Rebecca (1940) (du Maurier's stage adaptation of her novel)

Happy Christmas (1940) (short story)

Come Wind, Come Weather (1940) (short story collection)

Frenchman's Creek (1941)

Hungry Hill (1943)

The Years Between (1945) (play)

The King's General (1946)

September Tide (1948) (play)

The Parasites (1949)

My Cousin Rachel (1951)

The Apple Tree (1952) (short story collection, AKA Kiss Me Again, Stranger)

Mary Anne (1954)

The Scapegoat (1957)

Early Stories (1959) (short story collection, stories written between 1927–1930)[27]

The Breaking Point (1959) (short story collection, AKA The Blue Lenses)

Castle Dor (1961) (with Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch)

The Birds and Other Stories (1963) (republication of The Apple Tree)[29]

The Glass-Blowers (1963)

The Flight of the Falcon (1965)

The House on the Strand (1969)

Not After Midnight (1971) (short story collection, AKA Don't Look Now)

Rule Britannia (1972)

The Rendezvous and Other Stories (1980) (short story collection)

Non-fiction/

Gerald: A Portrait (1934)

The du Mauriers (1937)

The Young George du Maurier: a selection of his letters 1860–67 (1951)

The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë (1960)

Vanishing Cornwall (includes photographs by her son Christian, 1967)

Golden Lads: Sir Francis Bacon, Anthony Bacon and their Friends (1975)

The Winding Stair: Francis Bacon, His Rise and Fall (1976)

Growing Pains – the Shaping of a Writer (a.k.a. Myself When Young – the Shaping of a Writer, 1977)

Enchanted Cornwall (1989)

More here/

Published on August 31, 2015 04:59

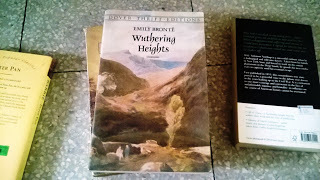

Wuthering Heights is Emily Brontë's only novel. Written b...

Wuthering Heights is Emily Brontë's only novel. Written between October 1845 and June 1846, Wuthering Heights was published in 1847 under the pseudonym "Ellis Bell"; Brontë died the following year, aged 30. Wuthering Heights and Anne Brontë's Agnes Grey were accepted by publisher Thomas Newby before the success of their sister Charlotte's novel, Jane Eyre. After Emily's death, Charlotte edited the manuscript of Wuthering Heights, and arranged for the edited version to be published as a posthumous second edition in 1850.

Wuthering Heights is Emily Brontë's only novel. Written between October 1845 and June 1846, Wuthering Heights was published in 1847 under the pseudonym "Ellis Bell"; Brontë died the following year, aged 30. Wuthering Heights and Anne Brontë's Agnes Grey were accepted by publisher Thomas Newby before the success of their sister Charlotte's novel, Jane Eyre. After Emily's death, Charlotte edited the manuscript of Wuthering Heights, and arranged for the edited version to be published as a posthumous second edition in 1850.Although Wuthering Heights is now widely regarded as a classic of English literature, contemporary reviews for the novel were deeply polarised; it was considered controversial because its depiction of mental and physical cruelty was unusually stark, and it challenged strict Victorian ideals of the day, including religious hypocrisy, morality, social classes and gender inequality. The English poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti referred to it as "A fiend of a book – an incredible monster ... The action is laid in hell, – only it seems places and people have English names there."

In the second half of the 19th century, Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre was considered the best of the Brontë sisters' works, but following later re-evaluation, critics began to argue that Wuthering Heights was superior. The book has inspired adaptations, including film, radio and television dramatisations, a musical by Bernard J. Taylor, a ballet, operas (by Bernard Herrmann, Carlisle Floyd, and Frédéric Chaslin), a role-playing game, and a 1978 song by Kate Bush.

More here/

Published on August 31, 2015 04:35