Dibyajyoti Sarma's Blog, page 12

January 22, 2020

Jaipur Literature Festival 2020 begins on 23 January.The ...

Published on January 22, 2020 22:41

January 21, 2020

Since Faiz Ahmed Faiz is the flavour of the season.

Published on January 21, 2020 11:27

January 12, 2020

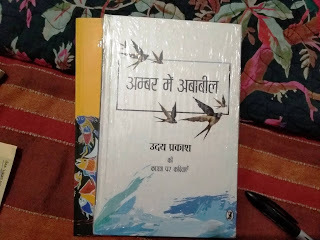

Selection of recently Hindi poetry collection.

Published on January 12, 2020 11:26

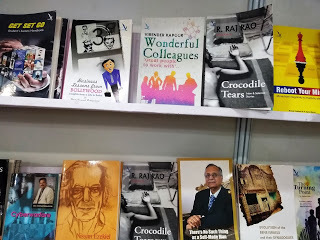

Find the book for which the cover design was done by your...

Find the book for which the cover design was done by yours truely.

Find the book for which the cover design was done by yours truely. HINT: There are two copies of the book in the picture.

Published on January 12, 2020 11:23

December 29, 2019

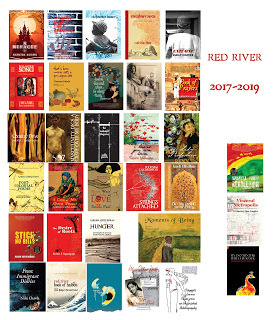

//A THANK YOU TO THE POETS & POETRY LOVERS FOR SUPPORTING...

//A THANK YOU TO THE POETS & POETRY LOVERS FOR SUPPORTING RED RIVER//It’s been two years since I really got involved with poetry publishing with Red River. Honestly, it’s an everyday struggle — for funds, for finding readership. I cannot call it a business yet (my friend calls it ‘a rich man’s hobby’; I’m trying my best not to get into loses so that I can keep the venture floating); and there’s still a lot to do — find a distributor maybe, or find more bookstores that are willing to keep poetry books on their shelves, and more importantly, find more people who want to invest in poetry.

Still, in the last two years, Red River is proud to publish 33 and a couple of more books, and I daresay, we are not doing too badly, thanks mostly to the wonderful poets, and the wonderful people, who trusted Red River with their manuscripts, and to my friends who purchased the copies.

Counting on your support.

Published on December 29, 2019 07:28

December 27, 2019

A half-review of Nabanita Kanangu’s A Map of Ruins For re...

A half-review of Nabanita Kanangu’s A Map of Ruins

For reasons galore and not limited to mainstream trade publishers’ studied disdain for young poets, in the recent years, poetry publishing in India has become something like an unorganised cottage industry, something like handicraft items, if you must have a comparison. There are poets everywhere; your Facebook timeline is crowded with them. Yet, there are very few you really want to seek out. There are very few published poets and even these books are from little known or obscure presses. There is no availability, and even when there is, in online retail sites, you are not adventurous enough to go and buy a poetry book. So it is special pleasure when you stumble across a poetry book you would come to admire. It is like going to flee market and finding a piece of rare artifact at a throwaway price. Nothing can compensate for it.

This is how I discovered Nabanita Kanangu’s A Map of Ruins. The book was a revelation. I wanted to write about it immediately. Yet, it was more fulfilling to savour her malleable voice than to comment on it. For a debut collection, Nabanita’s voice is measured, timid and almost taciturn, as if she has to force herself to write these lines.

As the title makes it abundantly clear, the book addresses the question of identity, and the idea of home, from the point of view of a third generation immigrant. And instead of wallowing in the tragedy of the lost homeland, the poet attempts to find an identity for herself.

When we talk about immigration and Diaspora in the context of Indian Writing in English, we cannot really avoid mentioning Salman Rushdie and his idea of Imaginary Homelands. Now that we have mentioned him, we will move on to something immediate, to the politics of memory of representation, which is romanticized and real at the same time.

In Nabanita’s case, it begins with this beautiful gem called ‘The Missing Tooth’.

There were reasons for which we had it painfully uprooted

and now the gap of the missing tooth

is an embarrassing memory in the mouth.

But the tongue is a child

habitually searching for a world

where it is not.

This is a fact. We now have a discourse of Partition Literature, which, as it has been nurtured in Delhi, tend of skew towards the North, while the east is largely neglected. When the East is mentioned, the focus is always on the erstwhile privileged class, the landed gentry, and the tenor of the tragedy has just one tune, how they lost their privilege and how they missed it. And again, the narrators of this tragedy are the ones who found their way to Kolkata.

(Recently, I saw a documentary where a son takes his ageing parents to see their ancestral homeland in Bangladesh, from where they had to flee soon after Independence. In is indeed a tragic story, and once back in homeland, which has changed beyond recognition, the couple remember their once-opulent homes, the large fields, the big ponds… I shed a tear or two, and yet, I could not help wonder about the others, the poor farmers who tilled the fields, who tended the ponds. There is a powerful scene towards the end, where the couple looking for the exact location of their houses meets an elderly man in white beard and a skullcap. With a glint in his eyes, he says he remembers the elderly woman’s father. “I was just a boy then, and he was kind to me, gave me sweets,” the bearded man says in proper Sylheti. Then he adds, “Those days, I did not know how to speak Bangla, as we had just arrived from Patna.” The camera then cuts to the ongoing search and the old man is forgotten. I wanted to get inside the screen and talk to the old man. I wanted to ask him if he missed Patna. I wanted to find the tenor of his tragedy.)

This is why Nabanita’s concern for identity within an “alien” culture has particular relevance.

Published on December 27, 2019 00:27

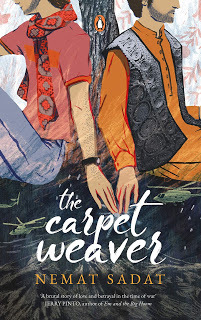

The following is a set of questions I prepared for Nemat ...

The following is a set of questions I prepared for Nemat Sadat after reading The Carpet Weaver.

1. I have a feeling that critics are going to compare The Carpet Weaver to The Kite Runner. But I think The Carpet Weaver is a more honest book, held together by the central love story. Why was it important for you to set the story within the specific time and time, in late 1970s?

2. It’s both a coming-of-age and coming out novel. Would you call it a gay novel?

3. Please forgive me if I am wrong, but there seems to an ‘intention’ in your telling of the story, where you mix personal identities with political identities — Maoism vs Taliban; homosexuality vs Islam. Is this correct?

4. Is it is so, did you have to compromise between activism and aesthetics (for example, Rustam’s confession to his own same-sex love felt like rushed)?

5. While researching on you, I found that you are the first person to come out in Afghanistan. Does this adds to a sense of responsibility as an author?

6. What you want your young Afghani readers to take away from The Carpet Weaver? And for the readers elsewhere?

7. It’s interesting that the book has been first published in India, where until recently homosexuality was a crime punishable by law. Your comment?

8. Would you say that the act of weaving carpet is metaphor for homosexuality in the book (Kanishka’s father doesn’t want him to be a weaver)?

9. Did you have to research on carpet weaving while writing the book?

10. I read that you are now working on your memoirs. Please tell us more.

11. Have you read the recent queer writings coming out from the subcontinent? If yes, please share some of the titles you liked.

Published on December 27, 2019 00:19

December 26, 2019

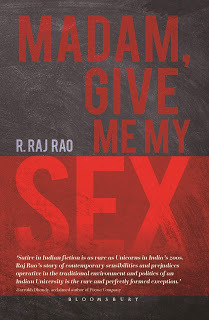

HOSHANG MERCHANT reviews Madam, Give Me My Sex by R Raj R...

HOSHANG MERCHANT reviews Madam, Give Me My Sex by R Raj Rao (Bloomsbury India, 2019/ Pp 300/ Price Rs 399)

R Raj Rao has written many novels and I have critiqued all of them in my various books on Indian gay writing. Madam, Give Me My Sex is his latest. It is his best. He talks of what he knows: the mad bureaucracy of an Indian university. He says it is a campus novel, but I did not think of Kingsley Amis. I thought instead of Joseph Heller’s lampooning of the American army in Catch 22.

No one can invent these incidents. They have to have happened; you can only embellish them in the writing. Raj was head of the department for a long time. They made his life miserable. Now it is payback time. Writing is the best revenge.

It is not a roman-a-clef though the real-life models are transparent behind the novelistic names of Raj’s characters for anyone who knows India’s English departments of the last 30 years. Raj calls it a satire (Swift is his guru). But in Swift’s day they had norms (values) and a writer could satirize anyone falling short. But now we live in a world of no values at all. I’d call this black humour.

Of course the figure of speech is hyperbole, most used by satirists. The foremost trope is scatology (Swift again). So we have rivers of excreta, clouds of farts and so on. Raj’s gay character is at the receiving end. But Raj redeems him by making him teach a learned gay literature course. Raj is something of this character himself and he is ultimately a kind human being, as we are told Pope was indeed.

You cannot be politically correct when you satirize. Everyone comes in for his serious put downs: the Dalits, the tribals who come into their jobs on reservations, the feminists. All holy cows are slayed and rightly so.

Raj has been a college and university teacher all his working life. He is most acute in his observations here. And I love the throwaway lines. An ex-student with Naxalite leanings is asked: “Who do you think you are, Varavara Rao?” Another naive MA student thinks ABVP stands for Atal Behari Vajpayee Prime Minister! And so on. The put-down is double-edged, aiming at both the character as well as the public idol with feet of clay.

I don’t like the title, but it will sell the book. It is actually the mispronunciation of a familiar word, which allows Raj to laugh at Indian pronunciations of English words.

Raj tells me he is now going to write a historical novel. I can’t wait to read it.

Published on December 26, 2019 00:31

November 4, 2019

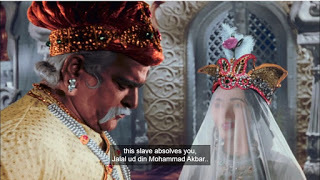

Here is the scene. After love and war, and all the dialog...

Here is the scene.

Here is the scene. After love and war, and all the dialogue-baazi, Akbar orders that Anarkali must die, and she, the slave girl, happily accepts her fate, for, her Prince is alive. And Raja Maan Singh asks, ‘What is your last wish?’

‘The Emperor cannot fulfill my last wish,’ she replies.

Akbar is beside himself. He is the Emperor; he can fulfill a slave girl’s dying wish. He demands that Anarkali states her wish.

‘I want to be the Queen of Hindustan before I die.’

Akbar screams. ‘Even at death’s door, you cannot let go of your ambition.’

‘My Lord,’ Anarkali pleads, ‘please don’t call my desperation my ambition. The Prince had promised that he would make me the Queen of Hindustan. I don’t want him to break his promise. I don’t want anyone to say that the future Emperor of the World cannot even keep a promise given to a slave girl.

‘No,’ Akbar replies, ‘the future Emperor of the World will keep his promise.

Next Scene.

Akbar shows a flower laced with intoxicants, places it on a crown and places the crown on Anarkali’s head, with the instruction that after the ceremony, before the night falls, she will give the flower to the Prince so that she remains unawares when she walks to her death.

She agrees.

Then she says, ‘Shahen shah ki is behisaab bakshishon ke badle me yeh kanij Mohammed Jallaluddin Akbar ko apna khoon maaf karti hain/ For his magnanimous generosity this slave girl forgives Mohammed Jallaluddin Akbar.’

Published on November 04, 2019 09:26

September 4, 2019

A half-review of The Carpet Weaver by Nemat Sadat Unfortu...

A half-review of The Carpet Weaver by Nemat Sadat

Unfortunately, critics are going to compare Nemat Sadat’s novel about a young Afghani man, Kanishka (I am not sure if it’s a common name in Kabul, but the use of this name to invoke the historical Kushana king feel forced), and his love for his classmate and its aftermath set just before and after the Soviet–Afghan War in the late 1970s, with Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner.

But this is an unfair comparison. As a piece of literature, Hosseini’s work is far more accomplished, yet the storytelling in The Kite Runner is consciously manipulative, largely targeted at a western audience. And you know it worked!

Sadat, the first person to come out as gay in Afghanistan, is far more honest and earnest and purposeful in The Carpet Weaver. The novel is a narrative of intentions. Sadat wants you to feel the complexities of same-sex love and its myriad manifestation in a country where the religion forbids it up close.

And the author succeeds, for most part.

Published on September 04, 2019 01:21