Dibyajyoti Sarma's Blog, page 11

September 5, 2020

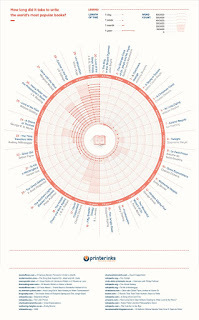

How Long Did It Take To Write The World's Most Popular B...

Published on September 05, 2020 08:26

May 10, 2020

Recently I discovered this neat thing — Penguin Classics ...

Recently I discovered this neat thing — Penguin Classics Cover Generator — https://nullk.github.io/penguin.html, and I went wild with it.

Check out some samples.

Check out some samples.

Published on May 10, 2020 14:45

April 22, 2020

So I reviewed Nandita Bose’s wonderful novel, EVERGLOW. H...

So I reviewed Nandita Bose’s wonderful novel, EVERGLOW. Have a read!

So I reviewed Nandita Bose’s wonderful novel, EVERGLOW. Have a read!https://www.sakaltimes.com/art-cultur...

Published on April 22, 2020 08:23

April 19, 2020

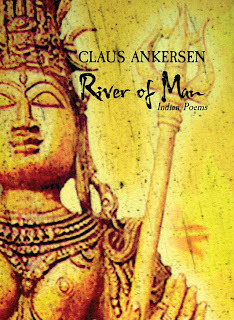

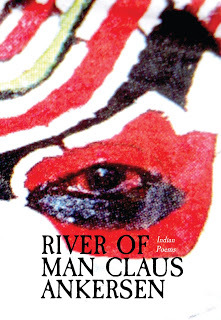

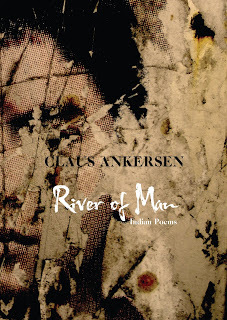

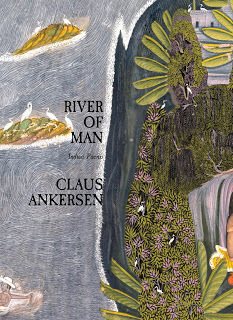

Some book covers that are eventually discarded...//

Published on April 19, 2020 08:36

April 13, 2020

So, I asked Uttaran Das Gupta a bunch of questions about ...

So, I asked Uttaran Das Gupta a bunch of questions about his new novel, RITUAL, and the good folks at Bengaluru Review has generously published in its April 2020 issue. Do have a look.

https://bengalurureview.com/crime-nov...

https://bengalurureview.com/crime-nov...

Published on April 13, 2020 08:28

April 5, 2020

Some book covers that are eventually discarded...//

Published on April 05, 2020 08:36

February 8, 2020

Queer literature still in the closet?A year after the HC ...

Queer literature still in the closet?

Queer literature still in the closet?A year after the HC verdict on Section 377, there was nothing much to write home about

After the law criminalising same-sex acts, Section 377 of the IPC, was repealed, again, in September 2018, you would think publishers would now be more open to bringing out queer content for mainstream readers. However, if you do a quick survey of books published in English in 2019, you’d know, this is not the case. To be honest, we have a sizeable number of titles with decidedly queer themes published in 2019, but none of them managed to attract the cultural zeitgeist.

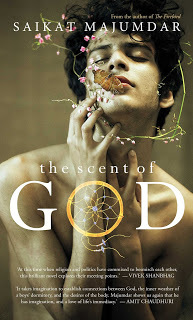

Two of the well-reviewed books with gay themes published this year were Saikat Majumdar’s The Scent of God and Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar’s My Father's Garden (released late 2019). But I am loath to include them in a list of queer literature, because in both the novels, the same-sex narrative is incidental to the overarching themes the authors are trying to portray.

Two of the well-reviewed books with gay themes published this year were Saikat Majumdar’s The Scent of God and Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar’s My Father's Garden (released late 2019). But I am loath to include them in a list of queer literature, because in both the novels, the same-sex narrative is incidental to the overarching themes the authors are trying to portray. Shekhar’s My Father's Garden is a study in masculinity, divided in three sections — lover, friend and father. The first section narrates a same-sex love affair in a college hostel, which is coloured by the lover’s heteronormative attitudes towards homosexuality. He doesn’t mind the sex act, but refuses to give the narrator the validity of his desire. Ultimately, the story ends in predictable tragedy with the narrator realising that his love was a compromise, and a sorry one.

The Scent of God is much more complicated in the context of gay writing from India, where Majumdar explore same-sex desire within the confined of a religious setting. Again, the narrative underscores the heteronormative attitude towards same-sex desire: you can fulfil your desires as long as you don’t talk about it. You can be a homosexual, but not gay. Post the SC verdict on Section 377, you’d expect same-sex desires to find a meaningful conclusion in Indian writing in English, but beneath the veneer of beautifully realised prose, targeted at a heterosexual audience, the attitudes towards homosexuality remains the same.

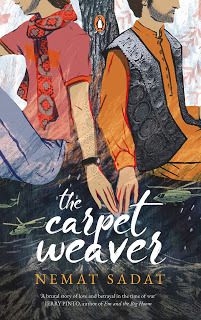

So it’s no surprise that best queer book published in India in 2019 was a novel by an Afghan-American author, Nemat Sadat. In The Carpet Weaver, Sadat tells an honest and harrowing coming of age story of being gay and proud. In a novel coloured by nostalgia and trauma — of pre-war Kabul, the refugee camp in Pakistan and of unrequited love — Sadat’s narrative remains steadfast in charting the development of the queer identity of his protagonist. This is a book India needs but doesn’t deserve.

So it’s no surprise that best queer book published in India in 2019 was a novel by an Afghan-American author, Nemat Sadat. In The Carpet Weaver, Sadat tells an honest and harrowing coming of age story of being gay and proud. In a novel coloured by nostalgia and trauma — of pre-war Kabul, the refugee camp in Pakistan and of unrequited love — Sadat’s narrative remains steadfast in charting the development of the queer identity of his protagonist. This is a book India needs but doesn’t deserve.This year, R Raj Rao, ‘the first Indian gay novelist’, published his fourth novel, Madam, Give Me My Sex, and unlike his previous works, there is hardly any gay content in the book. Instead, the novel is biting satire on higher education in India set in a fictional university, Oxford of the East. The narrator is gay, but it is not a gay novel by any stretch.

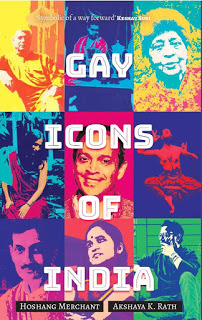

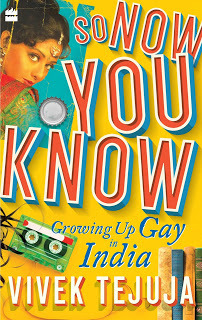

In the non-fiction category, we had two tongue-in-the-cheek narratives, often funny and illuminating — So Now you Know: Growing Up Gay in India by Vivek Tejuja and Gay Icons of India by Hoshang Merchant and Akshaya K Rath. Tejuja’s narrative is a coming-of-age story set in 1990s, before ‘gay’ was mainstream, before the arrival of the internet. Merchant and Rath’s book, on the other hand, is an unconventional biography of the so called gay icons of India, including the likes of Bhupen Kakkar, Agha Shahid Ali, Rituparno Ghosh, Amruta Patil, Ashley Tellis, R Raj Rao, and Merchant himself. The book is by no means a conventional biography, but a personal assessment of the personalities in question, often gossipy and sometimes savage.

In the non-fiction category, we had two tongue-in-the-cheek narratives, often funny and illuminating — So Now you Know: Growing Up Gay in India by Vivek Tejuja and Gay Icons of India by Hoshang Merchant and Akshaya K Rath. Tejuja’s narrative is a coming-of-age story set in 1990s, before ‘gay’ was mainstream, before the arrival of the internet. Merchant and Rath’s book, on the other hand, is an unconventional biography of the so called gay icons of India, including the likes of Bhupen Kakkar, Agha Shahid Ali, Rituparno Ghosh, Amruta Patil, Ashley Tellis, R Raj Rao, and Merchant himself. The book is by no means a conventional biography, but a personal assessment of the personalities in question, often gossipy and sometimes savage.So, do we give up the hope of seeing a viable sub-genre of queer literature emerging in India? Certainly not. There is hope yet, as we await the publication of the ambitious South-Asian queer poetry anthology, World That Belongs to Us, edited by Aditi Angiras and Akil Katyal in February 2020.

Published on February 08, 2020 00:14

February 3, 2020

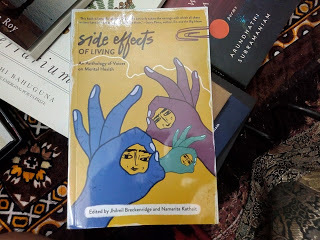

Side Effects of Living, editing by Jhilmil Breckenridge a...

Side Effects of Living, editing by Jhilmil Breckenridge and Namarita Kathait.

Side Effects of Living, editing by Jhilmil Breckenridge and Namarita Kathait.A collections of personal narratives of trials and triumps of living with mental health.

Featuring a piece by yours truely.

Published on February 03, 2020 04:47

February 2, 2020

The Myriad Meanings of Being Queer

THIS ARTICLE WAS FIRST PUBLISHED ELSEWHERE AROUND 2018, I THINK.

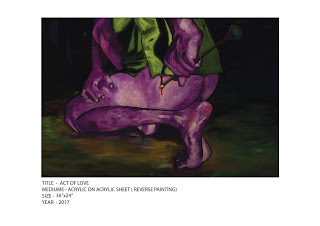

The exhibition ‘Me We’, curated by Myna Mukherjee of Engendered explores the intersection of sexuality, identity and art

The exhibition ‘Me We’, curated by Myna Mukherjee of Engendered explores the intersection of sexuality, identity and art

What’s queer art, anyway? Let’s just say that today, it defies an easy answer. However, one thing is clear. It’s no longer just about alternative sexualities; it encompasses broader issues of identity. This is especially true of visual arts. For years, there seemed to only two ways of representation — erotic and political, that is, if an artist received the opportunity to represent at all. For years, the only queer artist we knew seemed to be Bhupen Kakkar. Despite his strong academic antecedents and his obvious genius, it took him years to receive recognition. Then we had the stark photographs of Sunil Gupta, and political performances of Inder Salim, and intimate paintings of Balbir Krishan. But somehow all their works remained fringe curiosities, fodders for easy controversy which the mainstream press could convert into ‘news’ and move on.

All this is about to change with the exhibition, ‘Me We’ (notice the obvious mirror reflection of the two words), a visual arts exhibition curated by Engendered and presented by the American Center which was on view from 26 June to 8 July at the American Centre, Kasturba Gandhi Marg.

Myna Mukherjee of Engendered explained, “The idea behind the show was to move away from the status quo, not just in terms of representation, but also in terms of dissemination, where art is available, not just galleries, but also in emerges spaces like Instagram. We tried to incorporate all sorts of diverse factors. That obviously led us to include voices that are expressed not just through the lenses of identity and sexuality, but also through the lenses of binary codification of gender. In short, we wanted to include artists who celebrate the sense of being different.”

True, being different is the exhibition’s raison d'etre. But what caught our attention was how this difference manifests in the artists’ works. For one thing, queer art is no longer camp, but a serious endeavour. The exhibition proves that queer identity in India today is a many-splendoured thing, an idea which was literary explored by two artists from two diametrically opposite points of view.

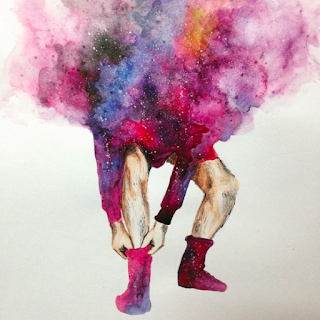

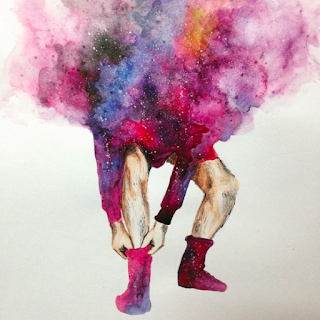

Aditya Raj’s watercolour on paper titled ‘Wearing the Cosmos’ shows a young man trying on socks as his upper torso explodes into multicoloured, star-filled cosmos. It’s an intriguing piece of work, like all his other pieces at the exhibition, were we notice the body of the subject but not his face. The face becomes the universe. There are different ways to read this, especially in Indian context, where being queer is still a criminal act (how the criminals are escorted to the court with their faces covered) and also a matter of shame. It’s interesting how Raj takes this idea of the hidden face and positivises it to incorporate the whole of cosmos.

Aditya Raj’s watercolour on paper titled ‘Wearing the Cosmos’ shows a young man trying on socks as his upper torso explodes into multicoloured, star-filled cosmos. It’s an intriguing piece of work, like all his other pieces at the exhibition, were we notice the body of the subject but not his face. The face becomes the universe. There are different ways to read this, especially in Indian context, where being queer is still a criminal act (how the criminals are escorted to the court with their faces covered) and also a matter of shame. It’s interesting how Raj takes this idea of the hidden face and positivises it to incorporate the whole of cosmos.

On the other hand, Renu Sharma’s watercolors and gouache on paper ‘Turning In’ is about finding the universe within, when we are one with the universe. It begins with a standard portrait of a woman defiantly looking at the viewers as her clothes reveals the aspects of the space itself. The work is a bold statement on connecting at different level, first with the body, then with the outside, and finally to encompass the whole of existence.

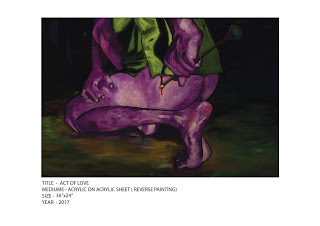

This idea of finding a body that suits the identity and celebrating the difference of the body is the theme of several other artworks. Gargi Chandola’s digital painting ‘Trans Passing’ is a literal shedding of identity to revel another, where we notice a changing room, with a man’s clothes strewn across and his face as a mask discarded on the floor, as the standing figure remove his skin as if it’s a body suit to reveal a intriguing and colourful female aspect inside.

This idea of finding a body that suits the identity and celebrating the difference of the body is the theme of several other artworks. Gargi Chandola’s digital painting ‘Trans Passing’ is a literal shedding of identity to revel another, where we notice a changing room, with a man’s clothes strewn across and his face as a mask discarded on the floor, as the standing figure remove his skin as if it’s a body suit to reveal a intriguing and colourful female aspect inside.

A series of four paintings by Balbir Krishan also explores the possibilities of trans-identity. It begins with post-apocalypse like landscape with a figure in a gasmask on. As you are drawn to the intricate design of the artwork, you notice how a flower has sprouted on the other end of the mask. This tonal shift from hopelessness to hope, finding an opportunity to thrive even in the most oppressive of situations is at once surprising and heartening. Elsewhere, Manmeet’s photograph, ‘Hidden’, plays with the idea of a woman with literal balls.

It’s very easy for a group show like this to appear lopsided, focusing on certain aspects and ignoring others. To its credit, ‘Me We’ goes out of its way to bring in the diversity in both presentation and representation.

So you have standard works, paintings, and photographs, but also other forms — a brass tongue behind a pair of scissors and nails to represent how minority voices are silenced; installations featuring a scrapbook to represent hidden designs (one intriguing shot shows a newspaper with the photograph of a dead militant, half-naked. How the image incorporates violence and eroticism within the same space is striking.); a GIF image; a mannequin wearing a designer burqua, with a mirror for the face, to reflect the visitor’s face on its own; and a comic strip which re-imagines the Cinderella story, where she is a man in drag. Never mind, the story ends in happily ever after mode and it’s brilliant.

“We obviously wanted to have established artists on our show to offer a sense of history, but we also wanted to have artists from across the country, from small town and villages.” Mukherjee said.

These new artists bring a unique flavour to the show, where queerness is just an aspect of the artist’s personality.

These new artists bring a unique flavour to the show, where queerness is just an aspect of the artist’s personality.

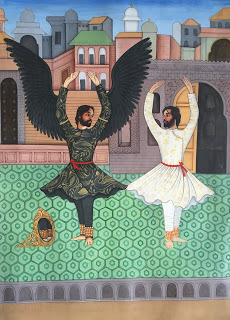

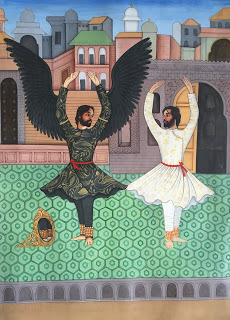

So we have Nikhil Bansal’s work which are inspired by Persian miniatures, an art form he confidently appropriates for his purpose. In ‘Let Me Fly’, we have a Kathak dancer and his mirror image, in darker shades and in wings, in a background which will typically represent a heterosexual scene.

Another painting by Aamir Rabbani shows a scene of furtive lovemaking between the sheets. However, what draws your attention is the top of the canvas, with trousers, shirts, bags, hanging from the walls, a single man’s room in the city, finding home away from home.

In brief, the exhibition celebrates the unconfinable and unflinching individualism of 25 artist voices, self-identified as queer. Mukherjee said the artists are working at the intersections of identity and life experience, genre and process. “Shattering mythologies of desire and intimacies, the works range from polished and seasoned to raw and sometimes even incomplete, exposed as they are to the vulnerability of love and loss that is immediate and personal,” she added.

So we have iconic photographers like Ram Rahman, Sonia Khurana, established artists like Balbir Krishan, Valay Gada, and Inder Salim, Satadru Sovan, emerging art feminists like Gopa Trivedi, Manmeet Devgun and Gargi Chandola (post-art project), radical young voices like Indira Lakshmi Prasad and Aditya Raj, Mohan Jangid, fearless new artists working at the intersection of religion and sexuality like Aaamir Rabbani & Adil Kalim, fierce young women artists from the North East like Jenny TS and Baishali Chetia; classical and renaissance painters like Saawan Taank, and Nikhil Bansal, the new millennial sketchers, illustrators and graphic artists, sci-fi fantasy makers and new media warriors like Ipshita Thakur, Pulkit Mogha, Oddbench and Renu Sharma and writer Dhritabrata Bhattacharjya Tato.

The best part of the show, and the artworks it showcased was the stern refusal to be pigeonholed into one category or another. It’s all fluid and personal and political at the same time. And perhaps the best part of the show was how the artists are rooted to their realities in India and still managing to hone their voices which are both unique and striking.

The exhibition ‘Me We’, curated by Myna Mukherjee of Engendered explores the intersection of sexuality, identity and art

The exhibition ‘Me We’, curated by Myna Mukherjee of Engendered explores the intersection of sexuality, identity and art What’s queer art, anyway? Let’s just say that today, it defies an easy answer. However, one thing is clear. It’s no longer just about alternative sexualities; it encompasses broader issues of identity. This is especially true of visual arts. For years, there seemed to only two ways of representation — erotic and political, that is, if an artist received the opportunity to represent at all. For years, the only queer artist we knew seemed to be Bhupen Kakkar. Despite his strong academic antecedents and his obvious genius, it took him years to receive recognition. Then we had the stark photographs of Sunil Gupta, and political performances of Inder Salim, and intimate paintings of Balbir Krishan. But somehow all their works remained fringe curiosities, fodders for easy controversy which the mainstream press could convert into ‘news’ and move on.

All this is about to change with the exhibition, ‘Me We’ (notice the obvious mirror reflection of the two words), a visual arts exhibition curated by Engendered and presented by the American Center which was on view from 26 June to 8 July at the American Centre, Kasturba Gandhi Marg.

Myna Mukherjee of Engendered explained, “The idea behind the show was to move away from the status quo, not just in terms of representation, but also in terms of dissemination, where art is available, not just galleries, but also in emerges spaces like Instagram. We tried to incorporate all sorts of diverse factors. That obviously led us to include voices that are expressed not just through the lenses of identity and sexuality, but also through the lenses of binary codification of gender. In short, we wanted to include artists who celebrate the sense of being different.”

True, being different is the exhibition’s raison d'etre. But what caught our attention was how this difference manifests in the artists’ works. For one thing, queer art is no longer camp, but a serious endeavour. The exhibition proves that queer identity in India today is a many-splendoured thing, an idea which was literary explored by two artists from two diametrically opposite points of view.

Aditya Raj’s watercolour on paper titled ‘Wearing the Cosmos’ shows a young man trying on socks as his upper torso explodes into multicoloured, star-filled cosmos. It’s an intriguing piece of work, like all his other pieces at the exhibition, were we notice the body of the subject but not his face. The face becomes the universe. There are different ways to read this, especially in Indian context, where being queer is still a criminal act (how the criminals are escorted to the court with their faces covered) and also a matter of shame. It’s interesting how Raj takes this idea of the hidden face and positivises it to incorporate the whole of cosmos.

Aditya Raj’s watercolour on paper titled ‘Wearing the Cosmos’ shows a young man trying on socks as his upper torso explodes into multicoloured, star-filled cosmos. It’s an intriguing piece of work, like all his other pieces at the exhibition, were we notice the body of the subject but not his face. The face becomes the universe. There are different ways to read this, especially in Indian context, where being queer is still a criminal act (how the criminals are escorted to the court with their faces covered) and also a matter of shame. It’s interesting how Raj takes this idea of the hidden face and positivises it to incorporate the whole of cosmos. On the other hand, Renu Sharma’s watercolors and gouache on paper ‘Turning In’ is about finding the universe within, when we are one with the universe. It begins with a standard portrait of a woman defiantly looking at the viewers as her clothes reveals the aspects of the space itself. The work is a bold statement on connecting at different level, first with the body, then with the outside, and finally to encompass the whole of existence.

This idea of finding a body that suits the identity and celebrating the difference of the body is the theme of several other artworks. Gargi Chandola’s digital painting ‘Trans Passing’ is a literal shedding of identity to revel another, where we notice a changing room, with a man’s clothes strewn across and his face as a mask discarded on the floor, as the standing figure remove his skin as if it’s a body suit to reveal a intriguing and colourful female aspect inside.

This idea of finding a body that suits the identity and celebrating the difference of the body is the theme of several other artworks. Gargi Chandola’s digital painting ‘Trans Passing’ is a literal shedding of identity to revel another, where we notice a changing room, with a man’s clothes strewn across and his face as a mask discarded on the floor, as the standing figure remove his skin as if it’s a body suit to reveal a intriguing and colourful female aspect inside. A series of four paintings by Balbir Krishan also explores the possibilities of trans-identity. It begins with post-apocalypse like landscape with a figure in a gasmask on. As you are drawn to the intricate design of the artwork, you notice how a flower has sprouted on the other end of the mask. This tonal shift from hopelessness to hope, finding an opportunity to thrive even in the most oppressive of situations is at once surprising and heartening. Elsewhere, Manmeet’s photograph, ‘Hidden’, plays with the idea of a woman with literal balls.

It’s very easy for a group show like this to appear lopsided, focusing on certain aspects and ignoring others. To its credit, ‘Me We’ goes out of its way to bring in the diversity in both presentation and representation.

So you have standard works, paintings, and photographs, but also other forms — a brass tongue behind a pair of scissors and nails to represent how minority voices are silenced; installations featuring a scrapbook to represent hidden designs (one intriguing shot shows a newspaper with the photograph of a dead militant, half-naked. How the image incorporates violence and eroticism within the same space is striking.); a GIF image; a mannequin wearing a designer burqua, with a mirror for the face, to reflect the visitor’s face on its own; and a comic strip which re-imagines the Cinderella story, where she is a man in drag. Never mind, the story ends in happily ever after mode and it’s brilliant.

“We obviously wanted to have established artists on our show to offer a sense of history, but we also wanted to have artists from across the country, from small town and villages.” Mukherjee said.

These new artists bring a unique flavour to the show, where queerness is just an aspect of the artist’s personality.

These new artists bring a unique flavour to the show, where queerness is just an aspect of the artist’s personality. So we have Nikhil Bansal’s work which are inspired by Persian miniatures, an art form he confidently appropriates for his purpose. In ‘Let Me Fly’, we have a Kathak dancer and his mirror image, in darker shades and in wings, in a background which will typically represent a heterosexual scene.

Another painting by Aamir Rabbani shows a scene of furtive lovemaking between the sheets. However, what draws your attention is the top of the canvas, with trousers, shirts, bags, hanging from the walls, a single man’s room in the city, finding home away from home.

In brief, the exhibition celebrates the unconfinable and unflinching individualism of 25 artist voices, self-identified as queer. Mukherjee said the artists are working at the intersections of identity and life experience, genre and process. “Shattering mythologies of desire and intimacies, the works range from polished and seasoned to raw and sometimes even incomplete, exposed as they are to the vulnerability of love and loss that is immediate and personal,” she added.

So we have iconic photographers like Ram Rahman, Sonia Khurana, established artists like Balbir Krishan, Valay Gada, and Inder Salim, Satadru Sovan, emerging art feminists like Gopa Trivedi, Manmeet Devgun and Gargi Chandola (post-art project), radical young voices like Indira Lakshmi Prasad and Aditya Raj, Mohan Jangid, fearless new artists working at the intersection of religion and sexuality like Aaamir Rabbani & Adil Kalim, fierce young women artists from the North East like Jenny TS and Baishali Chetia; classical and renaissance painters like Saawan Taank, and Nikhil Bansal, the new millennial sketchers, illustrators and graphic artists, sci-fi fantasy makers and new media warriors like Ipshita Thakur, Pulkit Mogha, Oddbench and Renu Sharma and writer Dhritabrata Bhattacharjya Tato.

The best part of the show, and the artworks it showcased was the stern refusal to be pigeonholed into one category or another. It’s all fluid and personal and political at the same time. And perhaps the best part of the show was how the artists are rooted to their realities in India and still managing to hone their voices which are both unique and striking.

Published on February 02, 2020 05:32