Jared C. Wilson's Blog, page 25

October 24, 2016

When the Gospel Sounds Like a Rumor

I have a new post at For The Church every Monday. Here’s a snippet from today’s entry, “Is Your Gospel an Urban Legend?”:

I have a new post at For The Church every Monday. Here’s a snippet from today’s entry, “Is Your Gospel an Urban Legend?”:

A church plasters the word grace everywhere but the substance of that word has not quite sunk down into the bloodstream. The pastor preaches on the gospel. The people read a lot of gospely books. They brand all their programming and resources with the word “gospel” and “grace.” And the message starts to attract messy people, sinners of all kinds, because that’s what happens when a message of grace is faithfully proclaimed. But the members aren’t really welcoming. They really treasure their own comfort. They value their preferences. They want their church to grow — until it does. And then it changes and change is disruptive, inconvenient. An “us vs. them” mentality creeps in, and eventually the new people start to creep away. Why?The message of grace requires a culture of grace to make it look credible. In other words, you can un-say with your life what you’re saying with your mouth.

Tim Keller talks about what happens when the gospel is on audio but the world is on video. It is hard for the message to compete if everything around us is screaming the exact opposite.

So how about you? Is your gospel credible? Do you talk a big game about it but treat others like that’s all it is — a game?

Does your gospel sound like an urban legend? Something you like to repeat but doesn’t quite sound true? Is it just a curiosity to you, a message of interest but not of impact?

Read the whole thing.

October 20, 2016

5 Things the Seeker Movement Got Right

Actually, these are more like five “right ideas” or five “right tracks” the “seeker sensitive” church growth movement started down before it veered hard into a fuller blown consumerism and became the attractional church. The yes, but‘s will be a reflex for most of my readers (as they are for me), and I have tried to anticipate them in my explanations, but for the most part, this really is a post about some good gifts the seeker church of yesteryear has given contemporary evangelicalism.

Actually, these are more like five “right ideas” or five “right tracks” the “seeker sensitive” church growth movement started down before it veered hard into a fuller blown consumerism and became the attractional church. The yes, but‘s will be a reflex for most of my readers (as they are for me), and I have tried to anticipate them in my explanations, but for the most part, this really is a post about some good gifts the seeker church of yesteryear has given contemporary evangelicalism.

1. The Emphasis on Every Member Ministry

In its grossest manifestation, this approach to member assimilation simply equates membership with volunteerism in the programming, but in the beginning, the concern about active membership was a good one. The seeker church was seeking (pardon the pun) to recover from the “country club”-type membership of its parents’ church, where all you had to do was walk an aisle, sign a card, and commit to give money. The original focus of the seeker church as it pertains to membership was to hold members accountable for ministry in the church. Adding spiritual gift assessments to the membership process was a positive step in the right direction. And the emphasis of making sure people placed in integral offices of leadership in the church were actually gifted for those offices was a great recovery of a long-neglected biblical teaching. Before this evaluation of the church’s assimilation of its members to service, churches just plugged willing souls into open slots, an expedient ruthlessness of its own that did enough damage itself. Rather than make an ear out of an eye with ear aspirations, the seeker church movement at least brought with it a re-focus on Paul’s teachings on the spiritual gifts in service of the church.

2. An Emphasis on Community Through Relational Groupings

Yes, much of the way churches “do” small groups today is a boondoggle waiting to be more widely exposed. But let’s give some credit where it’s due. The death of community was not the seeker church’s fault before it was the whole Church’s fault. And whatever problems we may (rightly) see in the one-size-fits-all, artificial “small groups as community” programs, the notion that community is what church life is all about, that people must connect relationally and “do life” together, is not something the emerging or missional movements innovated. It was the church growth movement, borrowing from the house churches, parachurches, and the ’70s Jesus Movement that recovered the notion of relational community over against the traditional church’s persistent substitute of cliques and classes.

3. An Incarnational Rethinking of Evangelism

The attractional church emerging from the seeker movement has largely bailed on the gospel. But in its nascence, it had the good idea that biblical evangelism was less about revivalistic “repeat this prayer” ticket-punching and more about living lives of witness to Jesus. By dispensing with the weekly altar call guilt-trip, and by attempting to train its congregants in relational evangelism, the seeker churches evince an admirable trust in the Holy Spirit for conversion and a proper expectation of its members to carry the message of Jesus beyond the church walls and into their daily encounters with the lost. Somehow the consumeristic impulse proved too strong, and I’d argue that the attractional movement has largely inverted this beyond the “seeker service” and effectively and implicitly suggested to its attendees to trust the worship experience for the evangelistic heavy lifting. But in its pioneering days, the seeker church had a practically proto-missional approach to Christians’ neighborhood and work life.

4. A Recovery of the Value of the Arts

This is not precisely an ecclesiological development, and the emphasis on the arts has clearly exploded in many cases into full-on entertainment-driven Sunday morning church performances and regrettable secular marketplace doppelgangers in the Christian entertainment market. But coming with the development of the church growth movement was the recovery of the value of artistry within the church and by the church as more than just polemics and propaganda. Again, we can obviously debate the quality of the art being produced in the Christian market these days—which clearly pales next to the art created by Christians in previous ages—but the valuing of creativity, the interest in aesthetics, and appreciation of artistry as not being worldly or unseemly is a huge improvement over against the culturally combative fundamentalism of the traditionalist church.

5. An Insistence that Faith Is for All of Life

The execution has been terrible, especially as the dominant teaching mode focusing on moralistic and therapeutic how-to’s has basically produced a largely nominal Christianity that is culturally conditioned and practically indistinguishable from the world. But the motive was sincere, I think. The early emphasis by the church growth movement was that Christianity applied to all of life, not just to one hour a week within the church walls. The emphasis on “life application” teaching—which, again, gradually and awfully subsumed proclamational preaching of the gospel—was itself a response to a real problem: namely, that non-Christians were not seeing the beauty of faith lived out, and Christians weren’t living out that beauty. The problem in execution is that the seeker/attractional church thought the solution to this problem was more law, not more gospel. Ironically, their execution in addressing this problem has only further created more Christians living compartmentalized lives. But the original notion toward application actually came out of a desire for our faith to direct, inform, and affect our families, schools, and workplaces. The seeker church wasn’t wrong to troubleshoot this problem, and we should follow that cue.

October 18, 2016

Jesus Is the Smartest Man Who Ever Lived

I have been amazed at the number of evangelicals who’ve been insisting lately that “moral values” have no place in considering who to vote for in this election. Aside from the fact that I don’t believe they even believe that—most will quickly move on to listing the moral disqualifications of Hillary (and Bill) Clinton—it’s an incredibly distressing and frustrating thing to hear. But it should be no surprise given the rate at which American evangelicals have learned to compartmentalize their “personal faith” from their vocations and public life while at the same time engaging a syncretism of their worship of God with their other objects of worship. (I talk a little more about this here.)

I have been amazed at the number of evangelicals who’ve been insisting lately that “moral values” have no place in considering who to vote for in this election. Aside from the fact that I don’t believe they even believe that—most will quickly move on to listing the moral disqualifications of Hillary (and Bill) Clinton—it’s an incredibly distressing and frustrating thing to hear. But it should be no surprise given the rate at which American evangelicals have learned to compartmentalize their “personal faith” from their vocations and public life while at the same time engaging a syncretism of their worship of God with their other objects of worship. (I talk a little more about this here.)

But we also see the effect of this compartmentalization in the way evangelicals have come to mimic the snarky “street smarts” of the conservative pundits, not all of them believers themselves. Greedy, lustful, predatory businessmen gain our support because “that’s just the way the world works.” “You’ve got to pick your poison.” “The world isn’t black and white.” “What other choice do we have than picking the lesser of two evils?” Et cetera, et cetera, ad infinitum.

Well, I call shenanigans on all that. The space-time economy of the kingdom of God is the way the world really is—at least, it is the way the world is really meant to work under God’s sovereignty, and Christians are not at liberty to pretend their true citizenship is there even if the ways of the kingdom don’t see immediately practical, convenient, gratifying, or otherwise successful. We are called to walk by faith, not by sight. And this means that Christians—assuming they really have received reborn hearts, transformed minds, and crucified flesh—trust that Jesus knows best about the way the world “really is.”

Jesus was the smartest man who ever lived. We have to get that through our thick skulls if we want to make a hill of beans difference for the kingdom in this world. So often we think of Jesus as spiritual in a way disconnected from reality. Jesus is religiously idealistic, we reason, but not (as they say) “street smart.” Jesus knows how things ought to be, but he’s not so incisive on how things really are. Jesus is a good teacher, but in the popular imagination pretty much a naïve one. Dallas Willard explains:

The world has succeeded in opposing intelligence to goodness . . . And today any attempt to combine spirituality or moral purity with great intelligence causes widespread pangs of “cognitive dissonance.” Mother Teresa, no more than Jesus, is thought of as smart—nice, of course, but not really smart. “Smart” means good at managing how life “really” is . . .

— Dallas Willard, The Divine Conspiracy (HarperCollins, 1998), 135.

The reality is that Jesus knows exactly how things really are, and in fact knows how things really are better than anybody else. We may look over the ethos of the Sermon on the Mount and find the whole thing utterly impractical toward getting ahead in the world—or even toward winning elections—but one of the underlying points of the Sermon is that getting ahead in the world is a losing gambit to begin with. We come to Jesus’s teaching looking for tips on playing checkers, when all along he is playing chess.

There is good reason for this. As God, Jesus is omniscient. He knows everything. In Mark 1:22 we read, “And they were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one who had authority, and not as the scribes.” The sort of authority Jesus is wowing them with here is not the kind simply accumulated through years of study. Jesus taught with the kind of authority that suggested he had mastered the material, that he was in fact the material world’s very master. His authority comes not from education but from authorship. “He told me all that I ever did,” the Samaritan woman declares (John 4:39). Yes, sister, because he foreknew it all, declared it all, and saw it all.

It makes total sense, then—real, actual, logical sense—to believe Jesus. He is no fool who believes the man who knows everything. And he is no fool who refrains from worldly wisdom even when other Christians cannot see the advantage of it.

(A portion of this post is a slightly edited excerpt from The Storytelling God.)

October 14, 2016

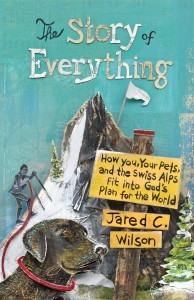

“The Story of Everything” Wins ECPA Top Shelf Cover Award

Big thanks to Nashville artist Wayne Brezinka, whose fantastic cover for my Crossway book The Story of Everything: How You, Your Pets, and The Swiss Alps Fit Into God’s Plan for the World has won an ECPA Top Shelf award for cover design.

Big thanks to Nashville artist Wayne Brezinka, whose fantastic cover for my Crossway book The Story of Everything: How You, Your Pets, and The Swiss Alps Fit Into God’s Plan for the World has won an ECPA Top Shelf award for cover design.

The Evangelical Christian Publishers Association presents the ECPA Top Shelf Award to promote and recognize outstanding book cover design in the Christian publishing industry.Top Shelf covers were announced and celebrated at ECPA’s annual PUBu.

The program focuses on the following DESIGN merits:

appropriateness for the market

level of conceptual thinking

quality of the executionCovers are judged by three top designers in the industry.

Go here to see the other winners.

This is my 3rd book to win this award for cover design, as my Crossway books on Christ’s parables and miracles — The Storytelling God and The Wonder-Working God — both won this award in 2014.

In these cases, you should definitely judge the books by the covers!

I am grateful for gifted artists who use their talents in service of the kingdom and in support of writing that seeks to exalt the glory of God in Christ above all. Congratulations, Wayne! And thanks for a great work of art.

Related:

Prodigal Church Wins World Magazine Book of the Year Award

October 13, 2016

The Gospel Kind of Christ-Centeredness

Now I would remind you, brothers, of the gospel I preached to you, which you received, in which you stand, and by which you are being saved, if you hold fast to the word I preached to you— unless you believed in vain. For I delivered to you as of first importance . . .

Now I would remind you, brothers, of the gospel I preached to you, which you received, in which you stand, and by which you are being saved, if you hold fast to the word I preached to you— unless you believed in vain. For I delivered to you as of first importance . . .

— 1 Corinthians 15:1-3

To be gospel-centered is to be Christ-centered. But as it pertains to the pursuit of holiness and obedience to God’s commands we may opt more often for the terminology “gospel-centered,” because without more qualifications, “Christ-centered obedience” can be misconstrued to imply simply taking Jesus as a moral example.

Jesus is our moral example, of course, but the power for enduring, joyful obedience comes not from trying to be like him, but in first believing that he has become like us, that he has died in our place, risen as our resurrection firstfruits, ascended to intercede for us, and seated to signal the finished work of our salvation.

Christ-centeredness properly qualified is truer than true. But many unbelievers have accepted (some of) Jesus’ teaching as the center of their self-salvation projects. Gospel-centeredness, however, tells us in shorter fashion what of Christ to center on: namely, his finished but eternally powerful atoning work.

Christ’s work is not all of Christ, but it is the doorway to all of him.

[T]he simple focus of my life is to be like Christ. That is why I must let the word about Christ dwell in me richly, as Colossians 3:16 says. That is why I must gaze at the glory of Christ, 2 Corinthians 3:18, so that I can be changed into his image. That is why Christ must be fully formed in me, Galatians 4:19. That is why if I say I abide in Him I must walk the way He walked, 1 John 2. I’m to be like Christ. This is the goal of my life.

So the goal of my life as a Christian is outside of me, it is not in me, it is outside of me, it is beyond me. I am not preoccupied with myself, I am preoccupied with becoming like Christ. And that is something that only the Holy Spirit can do as I focus on Christ. I focus on Him and the Spirit transforms me into His image.

— John MacArthur, Fleeing From Enemies [emph. added]

October 12, 2016

On Loving My Neighbor with My Vote

“And who is my neighbor?”

“And who is my neighbor?”

— Luke 10:29b

A commenter in the previous post asked this:

If the second greatest commandment is to love our neighbor as ourselves, and if we don’t then we are also failing the first greatest commandment to love the Lord God with all our heart, soul, and strength, then does that not mean that we are to choose to do the greatest good for our neighbor?

I think this is a great question, and since the gentleman leaving it is suggesting the most loving vote would be the one cast for Donald Trump, I thought I’d process through my response in a standalone post as a follow-up of sorts to the last.

This is a valid concern. We definitely should think of how our votes (or non-votes) affect our neighbors. As Christians, we ought to think how our postures toward politics and the electoral process demonstrate love for our neighbor.

Like this commenter, you the reader undoubtedly know that a religious leader once asked Jesus the deceptively complex question, “Who is my neighbor?” The response from Jesus, even though a story (Luke 10:30-37), is rather instructive. If we can apply it to our political situation today—and I agree with this commenter’s implication that we can—I would reason through it in relation to Trump’s candidacy like so:

- Donald Trump has consistently and unrepentantly accepted endorsement from white nationalist groups and echoed the rhetoric of white supremacist voices. This has given many non-white Americans a lot of valid cause for concern. Indeed, many of the black, Latino, and Asian voices I listen to have expressed some frustration that it took profane sexual words to prompt public outcry from some evangelical leaders, as if the constant race-baiting from Trump—which is not new but a consistent pattern over many years—is no big deal. If I support Trump, then, I tell my non-white neighbors that their concerns about dignity and racial justice are “no big deal” to me. Ergo, voting for Trump wouldn’t be loving to them.

- Donald Trump has said multiple incendiary things about both American and foreign Muslims, as well as refugees and immigrants. I have my own concerns about Islamic terrorism and insecure borders, and I believe these concerns can be valid, yet the lines of religious discrimination, racial hatred, and rejection of the alien and stranger are constantly getting crossed in Trump’s rhetoric, all of which violates biblical commands. If I support Trump, then, I support discrimination against my Muslim neighbors. If I support Trump, I by proxy support rejection of the foreigner seeking exile from persecution and pestilence.

- Donald Trump has said for many years now, including well into this campaign season, many disgusting, profane, abusive, and misogynistic things about women. I cannot repeat many of them. He brags about his affairs, he supports and invests in pornography, he boasts about sexual assault, he frequently comments on women’s looks and biological functions. If I support Trump, then, I fail to show love for my female neighbors. In fact, if I support Trump, I support the very ethos that fuels the abortion epidemic in the first place and fail to show love to the most vulnerable among us, including the poor, victims of sex trafficking, and of course, the absolutely most vulnerable among us—unborn children. (Incidentally, this also means I can’t vote for an explicitly pro-choice candidate, like Hillary Clinton for instance.)

- Donald Trump joked with Howard Stern that his cut-off age for sexual partners was probably 12 and that he would sleep with his daughter if he weren’t her father. He told Stern that it was okay to call his daughter “a piece of ***.” Joking about pedophilia and incest demonstrates just about the worst kind of character, just shy of actually engaging in these perversions. If I support Trump, then, I support the kind of character that finds the worst depravity imaginable humorous, and I fail to love victims of childhood sexual abuse and incest because I’m saying to them that their trauma is “just words,” just macho joking around.

- Donald Trump finds little support with younger evangelicals, particularly of the gospel-centered variety, a subset of whom have read and supported my work and have, for better or worse, indicated they have profited from my ministry. I have acquired this support through a consistent message of gospel-centrality that has worked itself out, in part, by rejecting pragmatic morality and political idolatry. To sell out that message now would be to sell out those who have encouraged me and supported me up to this point and to betray them with a philosophical 180 that reveals I was “just talk” all along. I fail to love gospel-centered Millennials if I support Trump, because I squander their good will and tell them their support for me was in vain. Further, I risk disillusioning them about the church and confirm for them their suspicions that older evangelicals care more for political power and influence than missional faithfulness from the margins.

So when I put all that together, I’ve got to come away with these two questions:

1. “If I vote for Trump, am I loving my neighbor?”

2. “Who is my neighbor?”

Well, to answer the first one in light of the second, from my perspective, if I were to vote for Trump, I would indeed be loving my neighbor—that is, if my neighbor were a middle-aged white Christian man.

Voting for Trump might be loving my neighbor—if my neighbor looked just like me. But I think that’s the very definition Jesus meant to rebuke the legalist for.

And I think there’s a reason Jesus made the heretic (the Samaritan) not a victim in the story, but the hero. And I further think there’s a reason why God calls us to seek not our own good, defining our neighbor by our own self-interest (Luke 10:29), but to find our good in the good of the city (Jeremiah 29:7).

But I say to you, “Love your enemies”

— Matthew 5:44

Love does no wrong to a neighbor; therefore love is the fulfilling of the law.

— Romans 13:10

October 11, 2016

Shall We Endorse Evil That Good May Result?

“And why not do evil that good may come?”

“And why not do evil that good may come?”

— Romans 3:8a

Or, to put it another way, “Do the ends justify the means?”

Or, to put it in more biblical terms, “Should we compromise what we know is true, honorable, just, pure, lovely, commendable, excellent, and worthy of praise if we think the result may be something good?”

Or, to be more specific, “Should we support a morally repugnant and unqualified person if we suspect some good may result from it?”

What is a Christian to do if casting a particular vote requires not just holding one’s nose but also closing one’s ears and covering one’s eyes and hurting one’s sisters and further fracturing relationships between races and violating other principles of Scripture related to keeping counsel of fools or hating our enemies? There are Supreme Court justices at stake, after all.

Perhaps there are better things than winning. Like an appeal to a good conscience before God (1 Pet. 3:21).

God used King David, an adulterer. (And, if we’re factoring in one’s views of abortion, also a murderer, by the way.) This is undoubtedly true. But the reality that God can use anybody and anything is not itself a commendation of endorsing anybody and anything. Biblically speaking, the truth is that the ends do not justify the means.

Let’s think about how the whole king of Israel thing happened. The people of God demanded a king (1 Kings 8). A political messiah. Someone to solve their problems and mete out justice. Why did they do this? Fear, mainly. Envy of other nations, also. God gave them what they wanted. He can use anybody. But he makes it clear that this desire is not godly. It’s not always a good thing when God “gives us what we want.” It’s not always a good thing to get what we want, even if our motives are sincere. No, it’s never a good thing to compromise godliness and cast our lots with evil even if we suspect something good may result. Sometimes the worst thing that can happen to us is for God to give us what we want. “Obey the voice of the people in all that they say to you, for they have not rejected you, but they have rejected me from being king over them” (1 Kings 8:7).

Evangelicals—ok, let’s be more specific: “old guard,” mostly white evangelicals—stand at a great precipice. They see the kingdoms of the world and they are afraid. They fear losing power. They fear losing control. They fear for their children’s safety and the future of their nation. They mostly desire something good. And here stands someone evil promising it to them. Just bow down a little bit. It’s not the end of the world. Everybody makes compromises. God can use anything.

God is sovereign over all. He appoints kings and princes. He rules over the rise of nations. And also the falls. God is even sovereign over the Devil! He is sovereign over the installation of wicked rulers. But he usually allows this to bring judgment, not peace.

Or maybe the position is not so grand. Maybe it’s humble, and we are just tired and hungry. We are starving for something good. In our anxious and famished state, the soup seems more immediately gratifying than the birthright.

In Romans 3:8, Paul addresses an accusation against him: “And why not do evil that good may come?” He calls this slander. And he says it leads to condemnation. Why? Not simply because it offends him. But because it offends the gospel and its divine Author.

If we truly trusted the sovereign Lord of all who can use anything, we would abstain from the endorsement of the morally disqualified—no matter their political party and no matter their promises—because God can use a non-vote as easily as a held-nose vote. And which, in fact, would display greater faith? I mean, if we’re using the Bible as our guide, does it appear to be a pattern that the Lord prefers to use the strong and the mighty and the big to accomplish his plans? Or does it seem like he seems to specialize in the people who can’t win?

Given the choice between a vote for a qualified underdog or a conscientious objection and a vote for the kind of leader the Bible calls wicked, which shows a greater faith? Which act of faith would display the clean hands without which no one can see the Lord?

The ends do not justify the means. And in our current quagmire, the ends are not even assured. They are barely even promised. They are more accurately held out as blackmail, as leverage.

Perhaps siding with an evil and hoping for the good is not our only option. Perhaps there is a third way. Maybe it’s siding with the good and trusting God’s best.

Trust in the LORD with all your heart,

and do not lean on your own understanding.

In all your ways acknowledge him,

and he will make straight your paths.

Be not wise in your own eyes;

fear the Lord, and turn away from evil.

It will be healing to your flesh

and refreshment to your bones.

— Proverbs 3:5-8

October 7, 2016

What the Church Needs Is a Reclamation of Biblical Supernaturalism

“O LORD, I have heard the report of you,

“O LORD, I have heard the report of you,

and your work, O LORD, do I fear.

In the midst of the years revive it;

in the midst of the years make it known;

in wrath remember mercy.”

— Habakkuk 3:2

I believe what we need in our day is not to presume the ineffectiveness of the Holy Spirit working through the preached Word but to repent of our decades of pragmatic methodology and materialist theology and to reclaim the proclamation of the gospel of Jesus Christ as the power of salvation for anybody, anywhere, any time. The United States desperately needs churches re-committed to the weird, counter-cultural supernaturality of biblical Christianity. And this means a re-commitment to rely on the gospel as our only power.

Creativity and intelligence can certainly adorn the gospel of grace, but there is no amount of creativity and intelligence that can waken a dead soul. Only the foolishness of the gospel can do that (1 Cor. 1:18). Not even sacrificial good works and biblical social justice can wake a dead soul, for the law has no power to raise in and of itself. Only the foolishness of the gospel can do that. And it is a shame that there are an increasing number of churches(!) that are blanching at the foolishness of the gospel these days. But Paul knows that the hope of the church and the world is the alien righteousness of Christ announced in that scandalous historical headline. “For Christ did not send me to preach the gospel with words of eloquent wisdom,” he says, “lest the cross of Christ be emptied of its power” (1 Cor. 1:17).

Paul knows that too often our creativity and intelligence don’t adorn the gospel, but obscure it. In some church environments, even though unwittingly, they replace it. But the apostle encourages us not to be ashamed—intentionally or even unintentionally —of the gospel, for it is the only power of salvation we’ve been stewarded. There. is. nothing. else. “I have resolved to know nothing among you except for Christ and him crucified” (1 Cor. 2:2).

I know some reckon that steady gospel preaching and revival prayer do not amount to much compared to human ingenuity and industriousness. But the Holy Spirit can do much more than we think or ask. Let’s not run ahead of him. Let this, from Maurice Roberts’s sermon “Prayer for Revival,” be our prayer as well:

It is to our shame that we have imbibed too much of this world’s materialism and unbelief. What do we need more than to meditate on the precious covenant promises of Holy Scripture until our souls have drunk deeply into the spirit of a biblical supernaturalism? What could be more profitable than to eat and drink of heaven’s biblical nourishment till our souls become vibrant with the age-old prayer for revival, and till we find grace to plead our suit acceptably at the throne of grace?

The Lord has encouraged us to hope in him still. O that he would teach us to give him no rest day or night till he rain righteousness upon us!

October 4, 2016

3 Nagging Problems with Andy Stanley’s Approach to the Bible

For Christ did not send me to baptize but to preach the gospel, and not with words of eloquent wisdom, lest the cross of Christ be emptied of its power.

For Christ did not send me to baptize but to preach the gospel, and not with words of eloquent wisdom, lest the cross of Christ be emptied of its power.

— 1 Corinthians 1:17

Pack a lunch.

By now, you are probably at least somewhat familiar with the firestorm resulting from NorthPoint Church pastor Andy Stanley’s teaching on the Bible and its suitability for (initial) apologetic/evangelistic engagement, most notably found in his recent teaching series but also in a conversation with Russell Moore at the most recent ERLC conference. He has been called everything from a liberal to a heretic, and not all of the criticism has reflected biblical wisdom and charity. Two of the better critical offerings came from Southern Seminary’s David Prince and Midwestern Seminary’s Rustin Umstattd. (There are many more. Google is your friend.)

Stanley has formally issued a response to the responses at Outreach Magazine. It’s this latter statement I want to spend some time interacting with, as I think his previous statements have been well-parsed and I find that—even after this attempted rebuttal and clarification—there are some glaring problems with Pastor Stanley’s approach to the Scriptures that not many are addressing. Certainly he isn’t addressing them himself. I am not certain he is even aware of them. Here, then, are three nagging problems I still have with Stanley’s use of the Bible:

1. Affirming the Bible’s inerrancy is not the same as trusting its sufficiency

I can’t speak for other critics, of course, but I for one never doubted that on paper Stanley would affirm inerrancy. Indeed, in his Outreach comments, he reaffirms his agreement with the Chicago Statement.

So for anyone out there who is still a bit suspicious, I affirm The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy. Heck, I studied under the man who co-authored the whole thing.

He is referring here, of course, to Norman Geisler, and I found this shared exchange between the two rather telling in a way Stanley probably doesn’t intend:

“Andy,” [Geisler] said, “I understand what you are saying but not everybody does. You need to put something in print so they know you hold to inerrancy.” I assured him I would. But I also assured him the they he referred to wouldn’t change their opinion because I’ve been in this long enough to know my take on inerrancy is not really the issue. He laughed. “I know, but you need to put it in print anyway.”

Stanley is right, I think. Inerrancy isn’t really the issue. At least, formal, theoretical affirmation of inerrancy is not the issue. Sure, one can quibble with his statements appearing to undermine the Old Testament accounts of the Jericho wall, and so on, but he is right that it is not his formal commitments that are problematic—it is the way he applies (or in this case, doesn’t apply) them.

As David Prince recently tweeted, “Affirming inerrancy in principle, while rejecting its sufficiency in practice, is like saying your wife’s perfect while having an affair.” This is exactly right. To put it in parlance Stanley’s tribe may be more inclined to consider: as the apostle James says, “Faith without works is dead.” If you say you have faith, but your deeds do not show faithfulness, your faith is under question. Further, affirmation of inerrancy without the practical application of sufficiency is dead. If you believe the Scriptures are totally reliable, why would you obscure them?

Further—and this is by far the biggest error of the entire attractional church enterprise—this approach to teaching/preaching presumes that the Bible is not living and active, that the gospel is not power, that the book is in fact kind of an old, crusty thing that really should be saved for after people have been softened up by our logic and understanding. In other words, Stanley believes the Bible needs our help, that his words are more effective than the Bible’s at reaching lost people. Which is just a way of saying that God’s Word isn’t good enough. A formal affirmation of inerrancy with a practical denial of sufficiency is actually an informal denial of inerrancy.

2. Sharing the gospel necessarily entails leaning on the gospel’s power.

I would be shocked if Stanley believed that anybody was ever argued into the kingdom. Surely he would agree that the best apologetic arguments and logical explanations have never been able to do what the good news of Christ’s finished work can do. Which is what makes it even more fascinating to read Stanley (and others) bending over backwards to explain that the Bible needs to come later in an evangelistic conversation. I can’t speak for all critics, but I agree with Stanley that apologetic/evangelistic conversations can take a variety of forms and begin in a variety of ways. We can ask questions, find common ground with our lost friends, and so on. But there’s never any doubt in my mind that it’s the good news of what Jesus has done that actually saves people. So it’s increasingly strange to hear people whose entire model of “doing church” is built around reaching the lost continually relegating the news of the gospel to codas at the end of sermons or only for special services altogether.

It’s beyond bizarre that in NorthPoint and other churches like it that are predicated on reaching the lost, every week you find not a steady does of gospel but a steady dose of how-to’s (law, basically) that not only can’t save anyone, but can’t even be carried out in a way that honors God unless and until someone’s heart is captured by the gospel.

Stanley spends many paragraphs hand-wringing over the new post-Christian era in America—a phenomenon, I’d argue, his mode of evangelicalism has been highly influential in producing—attempting to lay the case that his approach to preaching and ecclesiology is best-suited for turning the spiritual tide. Here is one statement from this excursus:

I’m not sitting around praying for revival. . . . I grew up in the pray for revival culture. It’s a cover for a church’s unwillingness to make changes conducive to real revival.

Well, it can be. But “not sitting around praying for revival”—apart from being a strawman—can also be a cover for a church’s embrace of pragmatism. Stanley goes on to say this:

Appealing to post-Christian people on the basis of the authority of Scripture has essentially the same effect as a Muslim imam appealing to you on the basis of the authority of the Quran. You may or may not already know what it says. But it doesn’t matter. The Quran doesn’t carry any weight with you. You don’t view the Quran as authoritative.

This is really important. Don’t miss what Stanley is unintentionally revealing here. He is saying that the Bible has the same effect on the lost as the Quran. There is zero room here for the actual reality of the Bible as God’s living Word. There is zero room here for the supernatural reality that the Bible carries a weight with lost people they don’t often expect it to! But this inadvertent nod to materialism and pragmatism is certainly expected from those with a proven track record of treating the Bible like an instruction manual rather than as the record of the very breath of God. If we truly believed the Bible was the very word of God, inspired by the Spirit and still cutting through to the quick, dividing joint and marrow, we wouldn’t for a second save it for special occasions. And we certainly wouldn’t equate its potential effectiveness with the Quran’s.

Stanley says:

I stopped leveraging the authority of Scripture and began leveraging the authority and stories of the people behind the Scripture. To be clear, I don’t believe “the Bible says,” “Scripture teaches,” and “the Word of God commands” are incorrect approaches. But they are ineffective approaches for post-Christian people.

This is a big assumption that places Scripture under the authority of “what lost people want.” Certainly Jesus and Paul did not find that “according to the Scriptures” lessened the effectiveness of God’s word for pre-Christian people. I’m not sure why we should expect God’s Word would be less effective for post-Christian people unless we believe the Holy Spirit is at some great disadvantage because people are smarter than they used to be or something.

Stanley’s approach puts the post-Christian in the driver’s seat; they are the ones with the authority, really. This doesn’t mean our preaching shouldn’t address questions and objections skeptics and doubters have. It simply means you don’t let the questions move you off reliance on the gospel’s power. (Tim Keller’s preaching is a good example of that which is undeniably gospel-rich and yet directly applicable to key concerns and challenges lost folks have.)

Later in the Outreach piece, Stanley cites Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 9:19-23 as a defense of using anything to reach people. But this of course is not what Paul says. He says “all possible means.” The hitch here is on what one deems possible. If we take what else Paul has said about sharing the gospel, it is quite difficult to conclude, as Stanley appears to do, that “anything goes.” This is a standard line in the attractional movement: “We’ll do anything to reach people for Jesus”—anything, it appears, but rely on the sufficiency of the Word of God.

No, when Paul says “all possible means,” he is speaking to his personal adaptability, not the gospel’s. In any event, I am not sure what point Stanley is trying to drive here, as I don’t know anybody who would deny the appropriateness of missional adaptability and contextualization. To me, this is another example of Stanley showing little understanding of his critic’s actual concerns or their own methods. Our concern is not about missional contextualization but about the place of the Word of God in the mission, and the place of God in the church (which I’ll get to in a minute).

If I may reiterate here an agreement I have with Andy Stanley (and nearly every other attractional church leader): we want lost people to know Jesus! We want the unsaved to be saved! We agree on this. And we also want to employ whatever is actually the most effective means of accomplishing this.

Stanley earlier said, simultaneously offensively and defensively, which is a neat trick:

Close to half our population does not view the Bible as authoritative either. If you’re trying to reach people with an undergraduate degree or greater, over half your target audience will not be moved by the Bible says, the Bible teaches, God’s Word is clear or anything along those lines. If that’s the approach to preaching and teaching you grew up with and are most comfortable with, you’re no doubt having a good ol’ throw-down debate with me in your head about now—a debate I’m sure you’re winning. But before you chapter and verse me against the wall and put me in a sovereignty-of-God headlock, would you stop and ask yourself a question: Why does this bother me so much? Why does this bother me so much—really?

Well, he’s just said we can’t use the Bible to argue that the Bible’s authority (sufficiency and potency) are “good enough,” so that’s convenient. He doesn’t want to hear “chapter and verse.” So that’s telling. But I’ll start with this: I did not grow up with the kind of gospel-centered expository preaching Stanley is denigrating here. In fact, I pretty much grew up in the kind of teaching Stanley has been part of pioneering. I was trained to preach and minister actually in the very model he’s espousing. I ate, slept, breathed this stuff and 15 years ago would have been right there alongside him saying everything he is saying. What I’ve discovered, actually, is that, contrary to Stanley’s approach to Scripture, the Bible’s words are powerful. They don’t need my help. And if we will proclaim Christ from the Bible clearly, passionately, and copiously, it will actually have the effect we all agree we want—people being saved by Jesus and growing in their walk with him.

I also submit that it is quite fascinating to discover that you will hear more good news in one of these “traditional”* churches doing gospel-centered expository preaching than you will in the attractional “5 steps to be a better whatever” churches every Sunday. I mean, let’s suppose we actually care about lost people hearing lots of good news. This leads me to my final critique here:

3. Reducing the Bible in or removing the Bible from your worship service is how you show you don’t know, biblically speaking, what a worship service is.

If I may speak to another issue I believe central to the more recent debate about the sufficiency and reliability of the Bible in worship gatherings and in evangelism and apologetic conversations with unbelievers: I think if we trace back some of these applicational missteps to the core philosophy driving them, we find in the attractional church a few misunderstandings. The whole enterprise has begun with a wrong idea of what — biblically speaking — the worship gathering is, and even what the church is.

In some of these churches where it is difficult to find the Scriptures preached clearly and faithfully as if it is reliable and authoritative and transformative as the very word of God, we find that things have effectively been turned upside down. In 1 Corinthians 14, Paul uses the word “outsider” to describe unbelievers who are present in the worship gathering. He is making the case for our worship services to be intelligible, hospitable, and mindful of the unbelievers present, but his very use of the word “outsider” tells us that the Lord’s Day worship gathering is not meant to be primarily focused on the unbelieving visitor but on the believing saints gathered to exalt their king. In the attractional church paradigm, this biblical understanding of the worship gathering is turned upside down—and consequently mission and evangelism are actually inverted, because Christ’s command to the church to “Go and tell” has been replaced by “Come and see.”

Many of these churches—philosophically—operate more like parachurches. And the result is this: it is the sheep, the very lambs of God, who basically become the outsiders.

This is by design in the attractional church. In an exchange on Twitter with a NorthPoint attendee a few weeks ago, he was making the case for treating the worship gathering like an evangelistic conversation with the lost and said to me, “Imagine you are in a coffee shop with an unbeliever…” I said to him (basically), “I don’t have to imagine that. I’ve been in that coffee shop and other places like it numerous times.” The point we agree on is that evangelistic conversations in coffee shops (or wherever) don’t need to sound like sermons. But it’s also this: the gathering of the saints for worship doesn’t need to sound like a coffee shop conversation with a lost person. This is a fundamental misunderstanding of what the worship service is. And of course this misunderstanding only breeds more errant practices, like the idea that you can conduct a worship gathering (or two or three) without any Bible in it. As if our very existence does not center on the power and authority of the Word of God. “Sorry, God, this morning we’re going to be ‘leveraging the power’ of stories.”

Stanley cites the example of Peter preaching to the Gentiles in Cornelius’s home, which in fact is a good example of one of one of those coffee shop-type evangelistic conversations. But it’s not a worship gathering. But in his example, Stanley still fudges a bit. He uses this exchange as proof that Peter does not appeal to the Bible’s authority, but in fact he does, just not in those words. You only need to look at the cross-references for Acts 10:34-43 to see how much Bible is present in Peter’s evangelistic presentation, and of course there aren’t much clearer demonstrations of “thus saith the Lord” than the synonymous “All the prophets bear witness” in 10:43.

Of this line (in v. 43), Stanley says, “It reads as almost an afterthought.” We’ll have to agree to disagree on that.

In any event, I note two things: Peter is not not relying on the Scriptures in his exchange, but this exchange is not an example of a Lord’s Day gathering of the church. There is not really a biblical precedent for turning the gathering of believers into a “seeker service.” (I know, because I used to think there was and I looked.)

In his last example, Stanley cites Paul’s preaching in the Areopagus. It’s a powerful scene, of course, but, again—it’s not a worship service.

Look, if all Stanley is saying that the phrase “the Bible says so” is unnecessary and sometimes unhelpful: okay. But I think he’s saying more than that. I think he’s saying that, effectively, we have biblical precedent for turning a worship service without a Bible into a gospel presentation without a gospel. And I think he’s wrong.

In his Outreach article Stanley subtly suggests that his critics don’t actually know any “post-Christians.” This is another standard self-defensive response, sort of the new “I like my way of evangelizing better than your way of not evangelizing.” Or a new take on the strawman about Calvinists, that they don’t evangelize. But it’s lame. And out of touch. Like Stanley’s strange rant about selfish parents in small churches, it demonstrates no awareness of the gospel-centered movement and its incredible commitment to church planting and multi-faceted approach to missional community. So it’s time to lay down the defensiveness. As Stanley himself notes, the spiritual state of the United States is not great. The number of professing Christians is in decline—even as the number of attractional megachurches increases. Are approaches like Stanley’s the frontlines of actual revival? No. In fact, as they continue to marginalize the Scriptures and treat the gospel like grandma’s wedding china, they are actually part of the problem.

I believe what we need in our day is not to presume the ineffectiveness of the Holy Spirit working through the preached Word but to repent of our decades of pragmatic methodology and materialist theology and to reclaim the proclamation of the gospel of Jesus Christ as the power of salvation for anybody, anywhere, any time. The United States desperately needs a church recommitted to the weird, counter-cultural supernaturality of biblical Christianity. And this means a recommitment to rely on the gospel as power.

An Appeal to Andy Stanley and Others Like Him

I’ve been inside this model and was a huge advocate for it. I know what it’s like to feel criticized by “traditional” church people who “don’t get it.” So I also know that for all the innovation and relevancy we espoused, we were also closed-off to considering criticism. My appeal to the attractional church folks is this: set aside the defensiveness and the idea that you’ve got it all figured out, just for a minute. Listen and consider. Don’t write off anybody who objects to your methods as legalistic or pharisaical or stuffy or eggheads or unloving or old-fashioned. Unstop your ears. Consider the possibility that sincere motives don’t baptize bad methods. And don’t be afraid of the question, “What does the Bible say about this?” It is not irrelevant to this debate.

I would like to turn your own challenge back around:

Are you willing to take a long, hard look at everything you’re currently doing…? Are you ready to be a student rather than a critic? We don’t have time for tribes. We don’t have time for the petty disagreements that only those inside our social media circles understand or care about. We’re losing ground. The most counterproductive thing we can do is criticize and refuse to learn from one another. So come on. If you believe in the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ, that’s all I need to know. And in light of what’s at stake, in light of who is at stake, perhaps that’s all you need to know as well.

I would only offer this: When it comes to bodily resurrections, our Lord quotes in his parable this:

“If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead.” — Luke 16:31

Our worship shows whether we truly accept God’s Word as our authority and submit to it.

— John Calvin

* Stanley and others in the attractional tribe frequently bring up the label “traditional” as a kind of scare-label, a boogeyman to use against their critics, ignoring the fact that the traditional church is really kind of gone already and most of the kinds of churches where criticism for the attractional model might come from run the gamut in worship styles, building aesthetics, and Sunday attire. But it’s easier for attractional leaders to be defensive by dismissing their critics as stuffy pharisaical institutional people.

—

Related:

Is Your Worship Service Upside Down?

How Your Preaching Might Increase Sin in Your Church

How to Uncheapen Grace in Your Church

8 Hallmarks of Attractional and Gospel-Centered Churches

September 30, 2016

Video: The Pastor as Shepherd

I was honored to close out the third annual For The Church Conference at Midwestern Seminary this week with a message from John 21 titled “The Pastor as Shepherd” (the fifth of five sessions making up the conference theme, Portraits of a Pastor). Video of my message is embedded below, or you can visit here to see an index of all the messages.