Jared C. Wilson's Blog, page 22

February 28, 2017

Prayer Isn’t Magic

The way some people talk about prayer owes more to New Age spirituality and witchcraft than biblical Christianity. I don’t want to name any names, but I recall when I was a teenager being taught about “spiritual warfare” in ways I cannot seem to find supported in the Bible. Sometimes God and Satan were cast as warring opposites, a kind of yin and yang balancing each other out, even while squaring off. Which side will win in the battle over your soul and the fate of the universe? Well, whichever side you support, of course.

The way some people talk about prayer owes more to New Age spirituality and witchcraft than biblical Christianity. I don’t want to name any names, but I recall when I was a teenager being taught about “spiritual warfare” in ways I cannot seem to find supported in the Bible. Sometimes God and Satan were cast as warring opposites, a kind of yin and yang balancing each other out, even while squaring off. Which side will win in the battle over your soul and the fate of the universe? Well, whichever side you support, of course.

Obviously it sounds really stupid and basically blasphemous when put that way. But books, songs, and movies were made for the evangelical subculture that reflected just that kind of warped theology of the spiritual plane. Jesus almost became a version of Tinkerbell, needing our “applause” to gain strength and prevail over defeat.

This sort of man-centered spirituality is at the heart of the modern-day prosperity gospel, particularly in the strain known as “Word of Faith.” Promoters of this religious scam regularly encourage followers to speak only positive words and warn them against bringing curses upon themselves with negative attitudes. Do you want health, wealth, and prosperity? Name them and claim them. Do you want to ward off disease and disaster? The power of your tongue can rebuke their effect upon your life.

1. Prayer’s power is outside of ourselves.

All of this kind of spiritual hoo-ha mistakes the real presence of spiritual power in the Christian’s life as existing for the glory of us, rather than the glory of God. By all means, pray big prayers and expect God to come through, but remember that prayer isn’t magic.

When some Christians talk about the “power of prayer,” one gets the impression that there is some force inherent in our words, sourced in ourselves, that can make or break reality. The “name it and claim it” crowd operates as if the one praying is in control rather than the one prayed to.

Is prayer powerful? Yes, definitely, but specifically because the One being prayed to is powerful. The one doing the praying is in fact by his praying demonstrating that he has no power in and of himself. That is functionally what prayer is—an expression of helplessness. If we were powerful, we wouldn’t need to pray.

2. Prayer’s power is capital-S Spiritual.

When James says that “the prayer of a righteous person has great power as it is working” (5:16), we need to take great care to notice that “as it is working” gives a shape to the prayer. Literally, this verse can be expressed this way: “the prayers that work”—or, “the effective prayers”—“have great power.” This tells us two things. First, some prayers don’t “work.” By this, I assume it is meant that we don’t always get what we ask for when we pray. We may ask God to provide a certain desire or heal a certain wound. Sometimes he says no. But second, we notice that the prayers that have effect, have great power. Where could that come from?

If you said you, go sit in the corner.

But you didn’t say that, did you? You know where great power comes from. You know when you’re frustrated in traffic, irritated with your family, triggered by a reminder of your past, tripped up by a recurring sin, or depressed by an inconsolable loneliness that “great power” is not something that comes to you naturally. It isn’t found “within”—at least, not within your natural self.

No, the power that effective prayer has is nothing and nobody less than the Holy Spirit of God, who not only hears the prayer, but carries the prayer and replies to the prayer, and even inspires the prayer!

But let’s take it a step further. Prayer isn’t magic, because we have no power in and of ourselves. Prayer is expressed helplessness. But also, prayer isn’t magic, because God isn’t helpless without our moving him or unleashing him or activating him in some way. I cringe every time I hear some well-intentioned preacher use the phrase “let God”—as in, “You have to let God take control of your life” and “You need to let God be God.”

First of all, God doesn’t need you to let him do anything. He isn’t restrained or controlled by you. God isn’t like some tethered toddler on a parental leash at the mall, struggling for freedom to have at the world around him. What saps we are if we think we have the power to “let God” do anything. He’s God. We’re not. Period.

So in prayer, you are not commanding the Spirit or summoning the Spirit like he’s a cosmic butler. In prayer, you are not in the place of control but in the place of submission. Prayer is effectively “spilling your guts,” because through prayer we bare our hearts, minds, and souls to the God who wants to be our friend. And the more we do this baring, the more we will experience of his power, even in our lowest and weakest of moments. Prayer is essentially weaponized weakness.

3. Prayer’s power is personal.

No, prayer isn’t magic. Prayer in practice is simply talking to God. We don’t need to make it more complicated than that. Of course, prayer is heavy-duty stuff; it is the act by which we say “Here I am” in response to God’s calling our name, our peeking up from behind the bushes a la Adam and Eve in response to God’s “Where are you?”

Prayer is the act that, through Jesus and by the Holy Spirit, puts us in the open embrace of the Father who listens with love. You can kneel, you can stand, you can sit, you can recline. You can clasp your hands or lift them. You can bow your head or raise it to heaven. You can close your eyes or behold creation. You can pray aloud or in your head. However you are going about it, we can’t complicate the act itself by ignoring the simplicity that all of it is talking to God.

One way to kill your prayer life is to overthink it. The best friendships you and I have are with people we feel we can be ourselves with. We feel most easily “at home” with the friends we don’t feel self-conscious around. This doesn’t mean that you can’t or shouldn’t plan your prayers or schedule time for prayer. It just means that the most vibrant prayer life is found in the one who is most willing to bring his whole self to God, willing to be himself before God, for better or worse.

February 24, 2017

God’s Grace Has a Timing of His Own

But God remembered Noah and all the beasts and all the livestock that were with him in the ark. And God made a wind blow over the earth, and the waters subsided.

But God remembered Noah and all the beasts and all the livestock that were with him in the ark. And God made a wind blow over the earth, and the waters subsided.

— Genesis 8:1

The chapter and verse numbers in the Scriptures are not inspired, of course, but there is something about Genesis 8:1 — specifically in the phrase “But God remembered Noah” — which is a nice correlation to Romans 8:1. In all of the apparent chaos, in the torrent, the danger, the death and destruction, there is therefore now no condemnation for those whom God is pleased to remember.

But Noah was remembering God too. How could he not? All other supports were gone, literally wiped away and overwhelmed by the earth-consuming deluge from heaven. Noah and his family weren’t steering that boat, far as we know. And as big as it was, it was nevertheless compared to the sea-covered planet a mere speck in the vast expanse of the raging torrent, like a cork bobbing about in the Pacific Ocean. God certainly becomes the believer’s only hope precisely when he has become the believer’s only hope.

When the storms are rising in your life, aren’t you closest to God then? Or do you fail to remember God even then and give in to despair and hopelessness and joylessness?

But we see in Genesis 8 that Noah remembered the God that remembered him. He remembered God primarily in 3 ways.

1. Noah remembered God’s timing.

It took him probably 98 years or so to build the ark. All along he had to be trusting in God’s timing, no? The temptation had to have arrived within hour one — “Did God really say…?” Certainly it did not abate hour after hour, day after day, year after year, decade after decade. But Noah walked each step with God, trusting in his timing. And after the thing was built, they went into the ark and were in there 7 days before the floods came! Those 7 days might’ve felt longer than 7 years.

But we also see in the flood’s aftermath, how closely Noah paid attention to God’s perfect timing. Notice this pattern seen by the keen eye over the text:

7 days of waiting for flood (Gen. 7:4)

7 days of waiting for the flood repeated (Gen. 7:10)

40 days of the flood (Gen. 7:17)

150 days of the waters prevailing (Gen. 7:24)

150 days of the waters receding (Gen. 8:3)

40 days of waiting (Gen. 8:6)

7 days of waiting (Gen. 8:10) – after the first dove

7 days of waiting (Gen. 8:12) – after the 2nd sending of the dove

There are patterns like this all over Scripture. But here in this precious palindrome, Noah’s echo and completing of the pattern shows how tuned-in he is to God’s timing.

Now, you may not be following days and hours that closely. Most of us don’t. I don’t. But as we pray and hope and struggle and fear, we have to remember that God’s timing is not our timing, that his timing is perfect. That when he says “No” to something or “Wait”, he has reasons based in his love for us, even if we don’t understand them.

The first deep acquaintance with grief came for my wife and I upon the miscarriage of our second baby. It was the Fourth of July weekend of 2002. We had both lost loved ones before then, but until then we had never been so personally affected, Becky especially.

I remember the first signs that something was wrong, causes enough to head to the doctor for answers. I remember most vividly sitting in a dim ultrasound room, while the technician ran the sonogram probe over my wife’s belly. The technician had an assistant with her, and they talked in very hush tones. They said nothing to us that I recall. They discussed what they were seeing. And what they weren’t seeing. They were keeping us in the dark until the doctor could speak to us, and that is exactly how we felt — like a darkness was overcoming us.

Of course when they finally told us the news. Miscarriage.

We named our baby Angel and we mourned for a long time. A year later we were pregnant again and due on — get this — July 4, 2003. The pregnancy had been difficult. Stress and other factors complicated our baby’s growth and caused Becky lots of discomfort and anxiety. After the miscarriage, we were pretty scared about how things might turn out, but our second daughter was carried all the way to term. I remember her birth, however, and while she came much more quickly than our first child, there was a complication. The doctor was concerned about her position, about the position of the umbilical cord. When our baby was delivered, she did not cry. The silence was unnerving.

I remember the nurse bringing our little baby over to the bassinet. The nurse looked concerned. I had been videotaping the event, but I put the camera down. I could tell something was wrong. Our baby was having trouble breathing. The more frantic the nurse looked, the more frightened I got. After multiple attempts to clear her throat and lungs, however, finally, climatically, our daughter let out the most beautiful wail I’ve ever heard.

We named her Grace. She was born on July 5th, one year plus one day from the day we first mourned Angel.

We don’t know why God decided to take Angel from us. And if we had our preference, we would have all 3 of our children here with us, alive and healthy. But God did a special thing with the timing for his own reasons, that we would come to trust him more deeply, to be refined by his Spirit in our grief. See if we were writing the story, we would have had Grace born exactly a year later, on July 4. That due date seemed just perfect. But God said, “No. One year and one day.” And so we learn that Grace has her own timing. And God’s grace has its own timing.

2. Noah remembered God’s priorities.

A curious thing here. Why did he send out a raven first, then a dove?

“At the end of forty days Noah opened the window of the ark that he had made 7 and sent forth a raven. It went to and fro until the waters were dried up from the earth” (Gen. 8:6-7).

A raven, first of all, is less particular than a dove. It went to and fro over the earth even while the place was still wet. A dove on the other hand will only nest where it is dry and clean. A raven is, well, more of a slob I guess.

But commentator Kent Hughes reminds us that a raven is not a bird considered ritually clean by God. Hughes writes, “Noah released the raven first because as an unclean bird it was expendable, since it was good for neither food nor sacrifice.” (We learn this in Leviticus 11:15 and Deuteronomy 14:15.) We learn a valuable lesson in Noah’s ordering of release of the birds for testing. The first thing he was willing to give up was something God considered unclean and unsuitable.

Is there not a valuable lesson for us in that? So often we protect things in our lives that God has actually called us to let go of. They may not even be things at all — our pride, our comfort, our schedules, our dreams — anything that gets in the way of trusting God and doing what he has called us to do.

Maybe you’re caught in a habit or in a relationship that you know doesn’t honor God, and it’s a huge area of compromise for you in your spiritual life. But you’re not willing to give it up. Why? Because you’ve come to treasure this habit or this pattern of behavior or this inappropriate relationship more than you treasure God. You’ve placed your priorities over God’s.

And you only do that when you don’t trust that God wants what’s best for you. We only do that when we think, “No, God doesn’t know what will satisfy and fulfill me. I know better than he.” But Noah was ready to lose first what was lose-able in God’s eyes.

3. Noah remembered God’s creative purpose.

One thing Noah had to be trusting was that God wasn’t saving him and his family for some postapocalyptic wasteland. Why would he preserve him and the animals simply to float around on the ark forever? I mean, if that’s what God called him to do, we have good reason to believe Noah would be willing to do that, but he was trusting and counting on God having a plan for restoration. He trusted that as high as the waters got, as dangerous as they seemed, as angry as God was about the sin that provoked him to such subsuming wrath, in the end, God did plan to bring him and his out unscathed, ready to resume the mandate given to his children to be fruitful and multiply.

If Genesis 8:1 predicts Romans 8;1, the subsiding of the waters in Genesis 8 also cast the shadow thrown by the great light of Romans 8:19-23:

For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. And not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies.

God’s plan for his beloved and his beloved creation is not annihilation but restoration.

Genesis 8:1, then, is a promise that as things get worse, God does not get further away, but actually more near. Brevard Childs says, “God’s remembering always implies his movement toward the object . . . The essence of God’s remembering lies in his acting toward someone because of a previous commitment.” If he takes much away, it is only because he wants us to treasure him only, and if we will treasure him only, how will he not also in the end give us all things besides? (Romans 8:32!)

When Noah was in the ark tossed to and fro on waves of destruction, God remembered him.

When Joseph was in prison, languishing away from crimes he didn’t commit, God remembered him.

When David was crying out in repentance of his horrific sins, God remembered him.

When Daniel was thrown into a den of lions to be torn to pieces, God remembered him.

When Daniel’s friends were thrown into the furnace b/c they refused to bow their knees to idols, God remembered them.

When the disciples were in the boat tossing to and fro from waves of destruction, crying out, “Remember us, lest we die!”, God remembered them.

And Christian, when you were at your moment of deepest danger — sinful and deserving of hell and eternal death — God remembered you (Rom. 5:6).

Look to the cross. It is the proof you need that God has remembered you and given you all that you need. His timing, his priorities, and his purposes are all revealed in Christ’s death and resurrection. He has not forgotten you. Remember that.

February 22, 2017

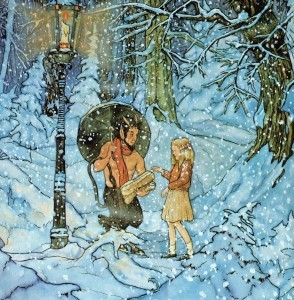

Why Narnia Isn’t Allegorical

Tim Challies’s excellent post this week on why Narnia’s Aslan is not the same as the divine characterizations in William Paul Young’s The Shack offered a literary side-note that addresses a pet peeve this English major and Lewisphile has held for a quite a while—the incorrect use of the word “allegory.” I address some of the ways people erroneously apply the allegorical sense to Jesus’s parables, for instance, in my book The Storytelling God, but in general, I notice more and more people referring to things that are simply symbolic or metaphorical as “allegorical,” making allegory a sort of catch-all category. But the history of literature does not allow such a sloppy application.

Tim Challies’s excellent post this week on why Narnia’s Aslan is not the same as the divine characterizations in William Paul Young’s The Shack offered a literary side-note that addresses a pet peeve this English major and Lewisphile has held for a quite a while—the incorrect use of the word “allegory.” I address some of the ways people erroneously apply the allegorical sense to Jesus’s parables, for instance, in my book The Storytelling God, but in general, I notice more and more people referring to things that are simply symbolic or metaphorical as “allegorical,” making allegory a sort of catch-all category. But the history of literature does not allow such a sloppy application.

Did C. S. Lewis write allegory? The answer is not as obvious as it seems. Because modern readers define and interpret allegory so loosely and broadly, it has become common to speak of the Narnia stories as allegories of the Christian faith (or at least to speak of the first book in the series as an allegory of the gospel story), or to speak of Lewis’s Space Trilogy as allegories of spiritual origins and conflict. But the fact is that C.S . Lewis published only one true allegorical work: The Pilgrim’s Regress.

It is important to consider what Lewis himself believed about Allegory, how he defined it. He may well have been wrong (and perhaps modernity has blurred the fine edges off of his definition to the point where he would be wrong today), but I think we cannot rightly call works of his allegorical if he himself denied they were.

The brief note at the beginning of Perelandra includes the curious disclaimer that none of the figures in the story is allegorical. I always thought this odd considering that the book so obviously included references to the biblical account of the fall, and that the hero Ransom was so obviously a Christ-figure. Indeed, the second book of Lewis’s Space Trilogy is the easiest of the three to read “allegorically.” But again, we must keep in mind that Lewis regards allegory as a specific genre with specific rules.

How then does he define allegory? Perhaps the clearest definition in the most common language comes via a letter to Mrs. Hook (found in Letters of C. S. Lewis, 12/29/58):

By an allegory I mean a composition (whether pictorial or literary) in which immaterial realities are represented by feigned physical objects, e.g. a pictured Cupid allegorically represents erotic love (which in reality is an experience, not an object occupying a given area of space) or, Bunyan, a giant represents Despair.

A more literary explanation is found in Lewis’s historical survey and critical appraisal of Allegory, The Allegory of Love:

On the one hand you can start with an immaterial fact, such as the passions which you actually experience, and can then invent visibilia to express them. If you are hesitating between an angry retort and a soft answer, you can express your state of mind by inventing a person called Ira with a torch and letting her contend with another invented person called Patientia. This is allegory.

To put it more simply:

For Lewis, allegory is when tangible things or figures represent intangible ideas—emotions, experiences, virtues, or vices. As an example, the character Christian in Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress represents Christianity or Christians in general, just as some of the characters Christian encounters in that allegorical work represent typical Christian struggles—fear, doubt, temptation, and so on.

An allegorical figure would represent an intangible concept. It is allegorical, then, when Johnny represents sacrifice, not when Johnny represents the person of Jesus. When figures represent not the intangible, but other things tangible (like other figures), then they become symbols. You could also perhaps use the word metaphor.

This is why the Narnia stories are not allegory either. Or, more specifically, this is why Aslan is not an allegorical figure of Jesus. In that same letter to Mrs. Hook, Lewis writes:

If Aslan represented the immaterial Deity, he would be an allegorical figure. In reality however he is an invention giving an imaginary answer to the question, “What might Christ become like if there really were a world like Narnia and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?” This is not allegory at all. So in Perelandra. This also works out a supposition. . . . Allegory and such supposals differ because they mix the real and the unreal in different ways.

Lewis goes on to elaborate, but a basic point is clear—the author did not regard Narnia or Perelandra (and I think, by extension, the first and third episodes of the Trilogy) as allegorical. He regarded the Narnia stories as “supposals,” a term I believe he invented himself to suit his purposes (although I could be wrong on that point). By “supposal,” Lewis meant to relate the imaginative speculation of his story, the exploration of the “what if?” he describes in the passage above.In his Letters to Children, he writes:

You are mistaken when you think that everything in the books “represents” something in this world. Things do that in The Pilgrim’s Progress, but I’m not writing in that way. I did not say to myself “Let us represent Jesus as He really is in our world by a Lion in Narnia”: I said “Let us suppose that there were a land like Narnia . . .”

None of this is to say that Lewis’s works are without symbolism. But if we want to interpret his writing correctly, we must at least do so according to the author’s rules. And if we are going to follow his rules for his writing, we must make the distinctions between allegory and symbolism and supposal that Lewis himself does.

This won’t keep anyone from reading the works as allegorical, or from saying they are allegories. The term has lost its meaning, really. And modern readers have inherited a slight reader-response critical mode from postmodern literary criticism without really knowing it. Nothing’s to keep you from reading Narnia as an allegory. Lewis acknowledges this:

Here, therefore, the critic has great freedom to range without fear of contradictions from the author’s superior knowledge.

Where he seems to me most often to go wrong is in the hasty assumption of an allegorical sense; and as reviewers make this mistake about contemporary works, so, in my opinion, scholars now often make it about old ones. I would recommend to both, and I would try to observe in my own critical practice, these principles. First, that no story can be devised by the wit of man which cannot be interpreted allegorically by the wit of some other man . . . Therefore the mere fact that you can allegorise the work before you is of itself no proof that it is an allegory. Of course you can allegorise it. You can allegorise anything . . . We ought not to proceed to allegorise any work until we have plainly set out the reasons for regarding it as an allegory at all.

— from “On Criticism” in ‘On Stories’ and Other Essays on Literature

February 21, 2017

Join Our New England Study Tour This May

Join me, Owen Strachan, Jason Duesing and more for Midwestern Seminary’s New England Study Tour this May 17-24, sponsored by The Center for Public Theology.

The New England region is home to a challenging culture with a rich heritage, and you will get to travel its storied roads alongside professors and fellow students to get an up-close meeting with this American mission field. We’ll walk where Edwards and Whitefield walked, visit everywhere from Yale to Harvard and coastal Maine to rural Vermont, meet with local pastors and church planters, and even enjoy some local eateries and coffee.

Why should you go?:

to get a firsthand encounter with NE history

to see the current gospel work in NE

to learn more about the distinctive theology that shaped NE

to see where the American missions movement began

to grow closer as a group and enjoy fellowship together

Tour stops:

Harvard, Yale, Princeton (JE archives—see actual “Sinners” sermon), Northampton (Edwards & Brainerd), Plymouth, Malden MA (Judson), Burlington VT (NETS), Portland ME, Boston, Providence (Brown & FBC), Newburyport MA (Whitefield burial), and more

Cost: $1900

The trip can fulfill one of the following classes (or 2, for $200 more):

Leadership Practicum

Church History II (grad and undergrad)

Baptist History

Church History Study Tour (elective)

For all those interested in attending this trip, please contact Austin Burgard at aburgard@mbts.edu to pay your deposit or to inform him of what class you will be taking.

Introducing: The Pastoral Training Center at Liberty Baptist

I am pleased to share with you a new initiative at Liberty Baptist Church in the Northland Kansas City (MO) that we hope will contribute to the next generation of solid, gospel-centered, mission-minded local church pastors. As our church has continued to grow, we’ve realized that our current efforts at discipling and training are not enough. A vital aspect of the gospel expansion taking place at LBC must be a more intentional process for serving men who are discerning a call to ministry.

We are pleased today to announce the launch of The Pastoral Training Center (PTC), Liberty Baptist Church’s formal residency program for the mentoring of men pursuing a call to gospel ministry. I will personally be leading this 18-month cohort-based process in which participants will collaborate in discussions on assigned readings, undergo group and one-on-one coaching, and receive on-the-ground ministry experience, which may include visitation, evangelism, teaching service in the church, preaching opportunities (at Liberty and beyond), and shadowing our pastor, Nathan Rose, as well as other leaders.

If you are a current or prospective student at Midwestern Seminary, this would be an ideal complement to your studies, and we do hope you’ll consider applying. Perhaps this opportunity can be part of your decision in choosing Midwestern for your seminary education. Our aim is certainly not to try replicating the seminary experience but instead to provide the experiential context and personal discipleship/coaching that will support and buttress your educational training. If you’re not a seminary student but are following a call to vocational ministry, PTC may still be for you, and we can customize your training to offset some of the deficiencies formal education would normally fill.

Interested? The first program starts this September and the deadline to apply is June 1. Space is limited to maximize the effectiveness for everyone involved, so don’t delay in applying.

Learn more about The Pastoral Training Center and apply here

February 14, 2017

5 Pastoral Proverbs That Stuck

A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in a setting of silver.

A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in a setting of silver.

— Proverbs 25:11

I took my first vocational ministry position the summer I graduated high school (1994), becoming the youth minister for Zion Chinese Baptist Church. (You read that right.) In the 23 years since, I’ve heard a lot of good words on ministry and ministry life, and while a lot has been good, a few choice bits of wisdom have stuck with me since I heard them and have proven truer and truer over the years. Here are just five.

1. “The core you start with isn’t the core you finish with.” — Bill Hybels

Hybels did not say this to me personally, but he said it in a workshop at the 1996 Willow Creek Church Leadership Conference. I don’t know why it stuck with me then—I was a youth pastor at a Willow model church, but I wasn’t thinking in terms of church planting or anything then. I’ve sifted out a lot I’ve heard from the church growth guys, but this one I’ve kept, and it’s pretty true, in a variety of ways. I’ve had guys I was close with, been on leadership teams and in the trenches with, decide the whole “living a Christian life thing” wasn’t for them. Your biggest fans can turn into your biggest critics, and often do. Mainly because they are your biggest fans because there’s some kind of idolatry they’re getting out of you, seeing you as a functional savior in some way. And then you disappoint them and BOOM: it’s all over. But even if nobody turns on you or falls out with you, the longer you go in ministry, you see how the seasons of life and the growth of a church or ministry takes the rose-colored glasses off of “doing ministry” with the same people forever. Some people get to do that. Most don’t. The core you start with is not the core you finish with.

2. “You must renounce comfort as the chief value of your life.” — Mike Ayers

Mike was my first pastoral mentor, the guy whose ministry actually kept my wife and me sane and in ministry after I’d had a bad experience at a previous church that almost made me give up church altogether. He was the first guy to really take me under his wing and trust me and empower me and take me seriously, even as a young punk. I served as a youth minister at his church and learned a lot, especially about loving the lost and building relationships. Mike and his family have been through a lot themselves, so when I heard him say this line in a sermon, I knew it came from a place of authenticity. It stuck with me. And it’s exceptionally important for all Christians, including pastors, who can get too comfortable with praise and growth and too despondent with criticism and conflict.

3. “Whatever your elders are, your church will become.” — Ray Ortlund

It’s no news to regular readers that Ray is my Yoda. I don’t remember the context of him saying this, but I remember him saying it, and I took it to heart. When we went about establishing eldership at Middletown Church in Vermont, I remembered this sound word of wisdom. So I looked not just for guys who met the biblical requirements for eldership, as high a bar as that is; I also tried to get guys with different personality types and outlooks and perspectives on theological non-essentials. And I also became a stickler for the biblical qualifications that many churches seem to gloss over—long-temperedness, gentleness, good public reputations, and so on. If my church is going to become like the leadership that is modeled for them, I wanted conformity on the biblical qualifications and orthodoxy but high maturity and as much diversity as possible otherwise.

4. “Don’t say something about someone you won’t say to them.” — Andy Stanley

I heard this in a Stanley teaching series called “Life Rules,” which with only a few caveats I recommend. I’ve used it numerous times. As you can imagine, I don’t resonate with a whole lot Stanley says these days, but this word of advice has stuck with me, and I’ve used it with great fruitfulness. In Christian community and in pastoral ministry, the opportunities for gossip and other relational sins are practically infinite. I am a great sinner who screws up a lot, but I’ve tried to maintain this rule for how I talk about people. If I have a problem with someone, I either swallow it, or I take it to them. If I’m not willing or able to do that, I certainly can’t talk about it with others. There’s so much crooked speech in the church, it’s ridiculous. Stanley’s advice is good for keeping the lines straight and the accounts current.

5. “You don’t just wipe away the web; you’ve got to crush the spider.” — Steven Taylor

Pastor Steve was one of my pastors when I was a kid. I think I was in the ninth grade when he said this in a sermon at Sandia Baptist Church in Albuquerque, New Mexico. I confess I have forgotten a lot of what he preached, but this line hooked into my brain and got me. For a kid with a tender conscience and struggling with lust, my eyes were opened to how I ought to approach the war on the flesh. Pastor Steve said you don’t just wipe away the effects of sin; you’ve got to be “extreme,” go to the source of temptation. In my adolescent way of thinking at the time, I went home and took the TV set out of my room. Since then, I’ve been able to apply this principle to even deeper actions of spiritual warfare, looking to the idolatrous roots of my behavioral sins as often as I can. But the advice is still good. Don’t just wipe away the web; crush the spider.

February 6, 2017

What to Include in Your Church’s Book Stall

Every Monday I have a new post published at For The Church. In today’s piece I’m recommending “10 Books for Your Church’s Book Table”. Why?

Every Monday I have a new post published at For The Church. In today’s piece I’m recommending “10 Books for Your Church’s Book Table”. Why?

The Evangelical Christian Publishers Association recently revealed the top 100 selling Christian books in 2016. When this list started making the rounds on social media, most ministry leaders I read were noticeably disappointed. And understandably so, as, apart from a few exceptions, the list appears full of superficial inspiration, silly gift books, and pop spirituality bordering on word-of-faith heresy.. . . If you’re a pastor, ministry leader, or otherwise concerned layperson, you are wisely asking yourself, “How do we work to fix this?”

Perhaps not the biggest solution but still an influential help is in the kinds of books we read ourselves, and especially in the kinds of books we quote from in sermons, recommend in our conversations and on social media, and otherwise share with others. Some pastors are wondering if a church bookstore might help.

. . . . [So] whether you have a large bookstall or an average one, if you’re concerned about shaping your congregation spiritually and intellectually according to the gospel, here are 10 books you should think about including . . .

January 31, 2017

Already, Not Yet, Right Now

The oracle of the word of the LORD to Israel by Malachi.

The oracle of the word of the LORD to Israel by Malachi.

“I have loved you,” says the LORD. But you say, “How have you loved us?” “Is not Esau Jacob’s brother?” declares the LORD. “Yet I have loved Jacob but Esau I have hated. I have laid waste his hill country and left his heritage to jackals of the desert.” If Edom says, “We are shattered but we will rebuild the ruins,” the LORD of hosts says, “They may build, but I will tear down, and they will be called ‘the wicked country,’ and ‘the people with whom the LORD is angry forever.'” Your own eyes shall see this, and you shall say, “Great is the LORD beyond the border of Israel!”

— Malachi 1:1-5

There is past tense and then future tense. There is “I have loved you” and there is “Your own eyes shall see . . .”

God through Malachi is addressing a half-hearted, spiritually corrupt covenant community. They have predicated their polluted religion on all that God is not presently doing. They are struggling financially and politically. They are muddling through while their enemies seem to prosper.

And God doesn’t say, “Hey, look around. Everything’s great!” He knows “looking around” is their problem. He beckons them to look back and to look forward.

This is a great reminder to us about how the gospel empowers us for daily living, even when we are in a bind or grind. When our world appears to be falling apart. When we can’t see our way out of the predicament or the grief we are in. The gospel bids us look back to what God has done in Christ on the cross and out of the tomb for his own glory and for us. “I have loved you” this says to troubled souls. And he bids us in the gospel to look forward to the blessed hope of Christ’s glorious return, our gathering together to him, our resurrection, our placement in an eternal wonderland where there are no more problems.

This is the already and the not yet of the gospel. This is the fantastic remembrance of what God has really done in history to save us and the fantastic anticipation of what God will really do in history to save us.

Now I would remind you, brothers, of the gospel I preached to you, which you received, in which you stand, and by which you are being saved, if you hold fast to the word I preached to you— unless you believed in vain.

— 1 Corinthians 15:1-2

January 23, 2017

The Quiet Messages of ‘Silence’

I recently read Shusaku Endo’s great 1966 novel Silence, about the 17th-century persecution of Jesuit missionaries in Japan. I thought it was great. If you’re a regular reader here, you noticed I made it my top book for 2016. Here’s what I wrote then:

Silence is a brief but indelible reflection on faith, doubt, and the inscrutable mystery of God. Mixed into this heady philosophical stew are provocative musings on contextualization, cultural adaptation, and religious adaptability. This is a literary masterwork, but I’d recommend it to any Christian interested in a window into the persecuted church and the clarifying darkness of suffering. It’s also interesting, I think, to consider the book’s crucial philosophical conundrums through a Reformational Protestant lens, and I look forward to discussing that especially with the book club at Midwestern Seminary who are currently reading this great book.

Last week I finally managed to catch Martin Scorsese’s long-anticipated (and long-developed!) cinematic adaptation, along with some of my fellow seminary book clubbers. Below are some scattered thoughts on the film, along the lines of Alex Duke’s own recent “thinking aloud.”

Why isn’t the movie proving more popular with evangelical audiences?

I’ve seen some wondering why folks aren’t getting out to support this film like they do other faith-based movies, especially since this one is ostensibly a much better faith-based film. Here’s perhaps America’s greatest filmmaker producing a movie that represents Christian values—and tells an historically important Christian story—and while we won’t go see it, we’ll go on complaining anyway that “Hollywood doesn’t represent our values.” Well, first, you should go see it. It’s a really good movie and a deep one. But second, I can think of a few reasons why evangelicals haven’t treated this movie the same way they did, say, The Passion of the Christ or, more recently, God’s Not Dead (or similar)—it didn’t have the marketing engine behind it. Mel Gibson’s The Passion stoked hunger for that film early and actively courted pastors, churches, and religious leaders. I am unaware of any such marketing blitz for Silence. Not to mention, the subject matter is really difficult to market. You can market a movie about Jesus to evangelicals really easyily. Evangelicals are experts in marketing Jesus. But Silence is about missionaries. In Japan. In the 1600s. This is not an easy sell to American evangelicals, even if you tried to sell it. Not to mention that the protagonists are Catholics.

Is the movie too Catholic?

This is pretty much like complaining that Moby Dick talks about boats too much. But I can see evangelicals shying away because of the historical connection here to Rome. This was a frequent topic of conversation among our book club—not that we thought the book was too Catholic, but that we processed the demanded apostasy in the story through our own Protestant bias. For instance if you asked many Reformed evangelicals to step on an icon of Mary, or even of Jesus, they wouldn’t hesitate. That wouldn’t be apostasy at all. In fact, many would regard the icon itself as blasphemous and stepping on it as an act of Christian devotion. But of course we know that persecutors of Christians will find whatever they think will work. For the Jesuits and their converts, to step on an icon of the blessed virgin (the fumie) is akin to stepping on her very face.

The story’s central problems are too Catholic.

The central tension of the novel and the film, though, has less to do with the plot devices related to the persecution and martyrdom and more to do with the crises of faith faced by the chief missionary protagonist Rodrigues (played excruciatingly well by Andrew Garfield) and the Japanese Christians he is seeking to shepherd. Rodrigues is plagued more painfully by God’s apparent silence over his ordeal than he is by the ordeal itself. Why won’t God say something? Again, as a good sola scriptura Protestant, I am compelled to mention that he has said something, he is saying something, and he does say something through his Word. Inappropriate or not, I confess I wondered throughout both the book’s and film’s depictions of this wrestling how a good evangelical understanding of revelation might have been a comfort. There is little evidence that Rodrigues’s familiarity with Scripture helps him sort out his theodicy, apart from the obvious recollections of the betrayals of Judas and—to a much lesser extent—of Peter.

And of course one’s belief about salvation is vitally connected to the crisis of faith in the story as well. Are we saved by faith alone or by our works? How might the doctrine of justification by faith affect the way one sorts through acts of apostasy, the choice between betraying one’s convictions and saving the lives of the suffering, and so on. Is it even possible to temporarily apostatize? If one has betrayed the faith, can he ever be restored? What if you’re just “going through the motions,” lying in order to save someone’s life? There is no strong sense among the missionaries that one of them may regain right standing with God once he’s made a public renunciation of his faith. At least, not until the cinematic coda, which I’ll get to in a minute.

There is also the notion of Christianity’s adaptation to Japan as a mission field. This is a central theme in the book, only referenced a few times in the movie. The contention is that Christianity doesn’t work in Japan, that Japan is a swamp in which the tree of Christianity cannot be planted, or at least, cannot grow and flourish. The interrogator Inoue and his men use this tack several times with Rodgrigues. And I wonder if perhaps they may be right, at least just a little bit. There are a lot of cultural trappings that come with Roman Catholicism’s version of Christianity. Perhaps it is not Christianity that cannot flourish in Japan but Roman Catholicism. Christianity, after all, is a faith given to contextualization, embraced by any culture around the world, precisely because it does not traffic mainly in outward conformity to cultural customs. Today there are approximately 509,000 Roman Catholics in Japan out of 1.9 million professing Christians. (Evangelicals, according to Operation World, make up about 600,000.) Is this telling? I don’t know, but perhaps it should be noted that the first Protestant/Anglican missionaries arrived in Japan 200 years after the Jesuits. I’d be curious to hear in the comments from you who are smarter on this stuff than I in am.

The best Christian in Silence is the worst one.

Kichijiro. The wild-haired, wide-eyed drunken apostate who watched his family burn at the stake. He repeatedly betrays his shepherds. He repeatedly endangers the villagers. He is regarded by all as clearly a hell-bound heathen. Even Father Rodrigues eventually hears his confession as a matter of clerical obligation, not in order to dispense eager pardon. Kichijiro is perhaps the film’s “worst Christian.” But here’s why I suspect Kichijiro is the film’s best—he is the one most readily aware of his own sin and frailty. While the priests are so sure of themselves—”I would never betray my Redeemer”—Kichijiro is honest. He knows he would. He is convicted by it and accepts his life as an outcast for it. He lives under a constant shadow of his own guilt, in fear for his own soul. Unlike the fabled Father Ferrera and later Rodrigues who eventually seem to make peace with their abandonment of the faith. So, okay, Father Garupe is really the best Christian because he never apostatizes and actually dies trying to save one of the martyrs, but after him, Kichijiro.

Silence isn’t your typical faith-based film, until it is.

As I mentioned above, evangelicals aren’t likely to flock to Silence, even after recent buzz from Christianity Today, World Magazine, and the like, mainly because it has everything going against it—historic and foreign settings, no obvious hero to root for, Catholic subject matter, and bladder-testing length. And let’s not forget a huge turn-off to evangelicals—ambiguity. The narrative artistry found in books and movies like Silence is not suited for tastes accustomed to treacly inspirational music on the radio and the kinds of books found in the ECPA’s Top 100. There is a reason you don’t find literary novels in the Christian bookstore. It’s the same reason movies with Silence‘s artistic pedigree don’t appeal.

But then there at the end, Scorsese adds a little something. It’s not in the book. The book is even more silent about the central narrative and theological tension. But the movie ends with that little visual addition, that clue about Rodrigues’s inner life that is meant, I suspect, to cue the audience to think there’s a neat resolution. On the one hand, I don’t care at all about this addition. I am not usually one to think film adaptations must follow their source; I judge the movies on their own, and if I fault a movie for departing from a book, it’s because the decision they made is worse, not because they didn’t treat the book like a sacred text. So I say all that to say, I don’t object to the inclusion of that final scene as a literary purist. It’s an interesting choice, and I know why Scorsese included it, and I can respect that. On the other hand, it plays very well into the dulled evangelical artistic—and theological—tastebuds. Evangelicals like resolution, they like happy endings. Scorsese (sort of) gave them one.

And evangelicals like the idea that they can be Christians without the world knowing it. They tend to believe they can pray a prayer or walk an aisle or sign a card and have that equal assurance. Once “saved,” always “saved.” The idea that you can inwardly be a believer while outwardly living however you want, is very much in keeping with the theological spirit of American evangelicalism. In that regard, Scorsese made a great choice. And a terrible one.

The Quiet Messages of “Silence”

I recently read Shusaku Endo’s great 1966 novel Silence, about the 17th-century persecution of Jesuit missionaries in Japan. I thought it was great. If you’re a regular reader here, you noticed I made it my top book for 2016. Here’s what I wrote then:

Silence is a brief but indelible reflection on faith, doubt, and the inscrutable mystery of God. Mixed into this heady philosophical stew are provocative musings on contextualization, cultural adaptation, and religious adaptability. This is a literary masterwork, but I’d recommend it to any Christian interested in a window into the persecuted church and the clarifying darkness of suffering. It’s also interesting, I think, to consider the book’s crucial philosophical conundrums through a Reformational Protestant lens, and I look forward to discussing that especially with the book club at Midwestern Seminary who are currently reading this great book.

Last week I finally managed to catch Martin Scorsese’s long-anticipated (and long-developed!) cinematic adaptation, along with some of my fellow seminary book clubbers. Below are some scattered thoughts on the film, along the lines of Alex Duke’s own recent “thinking aloud”.

Why isn’t the movie proving more popular with evangelical audiences?

I’ve seen some wondering why folks aren’t getting out to support this film like they do other faith-based movies, especially since this one is ostensibly a much better faith-based film. Here’s perhaps America’s greatest filmmaker producing a movie that represents Christian values — and tells an historically important Christian story — and while we won’t go see it, we’ll go on complaining anyway that “Hollywood doesn’t represent our values.” Well, first, you should go see it. It’s a really good movie and a deep one. But secondly, I can think of a few reasons why evangelicals haven’t treated this movie the same way they did, say, The Passion of the Christ or, more recently, God’s Not Dead (or similar) — it didn’t have the marketing engine behind it. Mel Gibson’s The Passion stoked hunger for that film early and actively courted pastors, churches, and religious leaders. I am unaware of any such marketing blitz for Silence. Not to mention, the subject matter is really difficult to market. You can market a movie about Jesus to evangelicals really easy. Evangelicals are experts in marketing Jesus. But Silence is about missionaries. In Japan. In the 1600’s. This is not an easy sell to American evangelicals, even if you tried to sell it. Not to mention that the protagonists are Catholics.

Is the movie too Catholic?

This is pretty much like complaining that Moby Dick talks about boats too much. But I can see evangelicals shying away because of the historical connection here to Rome. This was a frequent topic of conversation among our book club — not that we thought the book was too Catholic, but that we processed the demanded apostasy in the story through our own Protestant bias. For instance if you asked many Reformed evangelicals to step on an icon of Mary, or even of Jesus, they wouldn’t hesitate. That wouldn’t be apostasy at all. In fact, many would regard the icon itself as blasphemous and stepping on it as an act of Christian devotion. But of course we know that persecutors of Christians will find whatever they think will work. For the Jesuits and their converts, to step on an icon of the blessed virgin (the fumie) is akin to stepping on her very face.

The story’s central problems are too Catholic.

The central tension of the novel and the film, though, have less to do with the plot devices related to the persecution and martyrdom and more to do with the crises of faith faced by the chief missionary protagonist Rodrigues (played excruciatingly well by Andrew Garfield) and the Japanese Christians he is seeking to shepherd. Rodrigues is plagued more painfully by God’s apparent silence over his ordeal than he is the ordeal itself. Why won’t God say something? Again, as a good sola scriptura Protestant, I am compelled to mention that he has said something, he is saying something, and he does say something through his word. Inappropriate or not, I confess I wondered throughout both the book’s and film’s depictions of this wrestling how a good evangelical understanding of revelation might have been a comfort. There is little evidence that Rodrigues familiarity with Scripture helps him sort out his theodicy, apart from the obvious recollections of the betrayals of Judas and — to a much lesser extent — of Peter.

And of course one’s belief about salvation is vitally connected to the crisis of faith in the story as well. Are we saved by faith alone or by our works? How might the doctrine of justification by faith impact the way one sorts through acts of apostasy, the choice between betraying one’s convictions and saving the lives of the suffering, etc. Is it even possibleto temporarily apostasize? If one has betrayed the faith, can they ever be restored? What if you’re just “going through the motions,” lying in order to save someone’s life? There is no strong sense among the missionaries that one of them may regain right standing with God once he’s made a public renunciation of his faith. At least, not until the cinematic coda, which I’ll get to in a minute.

There is also the notion of Christianity’s adaptation to Japan as a mission field. This is a central theme in the book, only referenced a few times in the movie. The contention is that Christianity doesn’t work in Japan, that Japan is a swamp in which the tree of Christianity cannot be planted, or at least, cannot grow and flourish. The interrogator Inoue and his men use this tack several times with Rodgrigues. And I wonder if perhaps they may be right, at least just a little bit. There are a lot of cultural trappings that come with Roman Catholicism’s version of Christianity. Perhaps it is not Christianity that cannot flourish in Japan but Roman Catholicism. Christianity, after all, is a faith given to contextualization, able to be embraced by any culture around the world, precisely because it does not traffic mainly in outward conformity to cultural customs. Today there are approximately 509,000 Roman Catholics in Japan out of 1.9 million professing Christians. (Evangelicals, according to Operation World, make up about 600,000.) Is this telling? I don’t know, but perhaps it should be noted that the first Protestant/Anglican missionaries arrived in Japan 200 years after the Jesuits. I’d be curious to hear you who are smarter on this stuff than I in the comments.

The best Christian in Silence is the worst one.

Kichijiro. The wild-haired, wide-eyed drunken apostate who watched his family burn at the stake. He repeatedly betrays his shepherds. He repeatedly endangers the villagers. He is regarded by all as clearly a hell-bound heathen. Even Father Rodrigues eventually hears his confession as a matter of clerical obligation, not in order to dispense eager pardon. Kichijiro is perhaps the film’s “worst Christian.” But here’s why I suspect Kichijiro is the film’s best — he is the one most readily aware of his own sin and frailty. While the priests are so sure of themselves — “I would never betray my Redeemer” — Kichijiro is honest. He knows he would. He is convicted by it and accepts his life as an outcast for it. He lives under a constant shadow of his own guilt, in fear for his own soul. Unlike the fabled Father Ferrera and later Rodrigues who eventually seem to make peace with their abandonment of the faith. So, okay, Father Garupe is really the best Christian because he never apostasizes and actually dies trying to save one of the martyrs, but after him, Kichijiro.

Silence isn’t your typical faith-based film, until it is.

As I mentioned above, evangelicals aren’t likely to flock to Silence, even after recent buzz from Christianity Today, World Magazine, and the like, mainly because it has everything going against it — historic and foreign settings, no obvious hero to root for, Catholic subject matter, and bladder-testing length. And let’s not forget a huge turn-off to evangelicals — ambiguity. The narrative artistry found in books and movies like Silence are not suited for tastes accustomed to treacly inspirational music on the radio and the kinds of books found in the ECPA’s Top 100. There is a reason you don’t find literary novels in the Christian bookstore. It’s the same reason movies with Silence‘s artistic pedigree don’t appeal.

But then there at the end, Scorsese adds a little something. It’s not in the book. The book is even more silent about the central narrative and theological tension. But the movie ends with that little visual addition, that clue about Rodrigues’ inner life that is meant, I suspect, to cue the audience to think there’s a neat resolution to walk away with. On the one hand, I don’t care at all about this addition. I am not usually one to think film adaptations must follow their source; I judge the movies on their own, and if I fault a movie for departing from a book, it’s because the decision they made is worse, not because they didn’t treat the book like a sacred text. So I say all that to say, I don’t object to the inclusion of that final scene as a literary purist. It’s an interesting choice, and I know why Scorsese included it, and I can respect that. On the other hand, it plays very well into the dulled evangelical artistic — and theological — tastebuds. Evangelicals like resolution, they like happy endings. Scorsese (sort of) gave them one.

And evangelicals like the idea that they can be Christians without the world knowing it. They tend to believe they can pray a prayer or walk an aisle or sign a card and have that equal assurance. Once “saved,” always “saved.” The idea that you can inwardly be a believer while outwardly living however you want, is very much in keeping with the theological spirit of American evangelicalism. In that regard, Scorsese made a great choice. And a terrible one.