Sue Burke's Blog, page 68

May 14, 2014

Four-letter words

Here’s a simple but addictive word game that my students liked to play when I was teaching English as a second language:

Take any four-letter word, let’s say “book.” You can change any single letter or you can change the order of the letters (but not both) to make another word. The addictive thing about this game is that there is always another word. For example:

book

look

lock

lick

lice

mice

mace

came

cape

… to infinity and beyond!

You can play this game online (but without the letter switchero, which makes it easier) here:

http://robinwords.com/game/

A variation of this game is called Word Ladder, Word-links, or Doublets. It was invented by Lewis Carroll on Christmas Day, 1877. In this game you start with a given word and turn it into another word, sometimes with a contest to use the fewest number of steps. For more fun, the words can relate to each other in some way. For example:

wine

wins

wits

wets

bets

bees

beer

This game works with most three-letter and five-letter word pairs, too.

— Sue Burke

May 8, 2014

The real thing

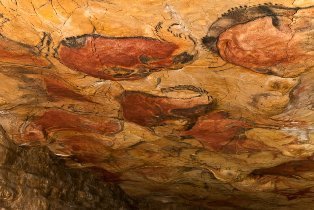

In Paleolithic times, 18,500 years ago, pictures of bison, horses, and other animals were painted on the ceiling and walls of a cave in northern Spain near what is now the town of Santillana del Mar. One artist in particular possessed genius-level skill and used the natural uneven contours in one room’s ceiling to create vibrant works with a three-dimensional effect.

Then 13,000 years ago, a rock fall closed off the entrance to the cave.

The cave opening was rediscovered in 1868 by a hunter, but since there are many caves in the area, it didn’t seem important. In 1879, an amateur palaeontologist, Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, investigated it looking for stone tools and brought his eight-year-old daughter María. She wandered into the room now called the Great Hall and came running back. “Look, Papa, oxen!”

This was the first find of Paleolithic cave art, and no one could believe it for two decades until more art was discovered. Although the same artist may have worked in other caves, Altamira remains the “Sistine Chapel” of prehistoric cave art.

That’s why everyone wants to see it. In 1973 alone, 174,000 visitors hiked through the modest-sized cave. But the art had been made with mere charcoal and natural rusty ochre pigments, and the presence of so many sweating, breathing, germ-covered human beings changed the cave’s climate and endangered its paintings. Since then visits to the cave have been restricted or banned altogether. Instead, in 2001, a museum and reproduction of the cave opened nearby, drawing an average of 250,000 visitors each year.

But now, if you’re very lucky, you can visit the cave again – the real cave, not the imitation. This year as an experiment, starting in February, five visitors are chosen by lot among those present one random day of the week to visit the cave in person, with a guide, for a mere 37 minutes, only 8 minutes in the Great Hall, wearing disposable coveralls, hats, face masks, and special shoes. They may not touch the rocks or take photos.

These visits will end in August, then their effect on the cave will be analyzed: rock and air temperature, microbiological contamination, humidity, carbon dioxide, and other possible changes.

Two of the first five visitors admitted they saw little difference between the original and the copy in the museum, except that the lighting was better for the copy. The head of conservation at Altamira, Gaël de Guinche, insists, however, “Nothing compares to the original. It isn’t just a question of the paintings, it’s the place, the humidity, the darkness, the cold, the experience itself.” He himself has visited the cave only twice “because I know it’s fragile.”

All the first visitors agreed on how impressive the original was and how bright and vivid the paintings were. One added, “The most exciting thing isn’t the cave. What truly impressed me is the passion of the people who take care of it.”

If you can’t get to Altamira, you can see reproductions in several places in the world, including an underground exhibit in the garden at the National Archeolological Museum in Madrid. I’ve visited a couple of times, since it’s only two kilometers from my house. An outer room explains the history and importance of the cave. An inner room displays a copy of the painted ceiling.

Although the lighting is subdued, you won’t believe you’re in a cave or even a pseudo-cave. It’s a cellar room. But the art is faithful, you can stay as long as you like, and reclining benches make staring upward a little more comfortable. And since nowhere near a quarter-million people visit each year, you can study the art in relative solitude.

Still, I can’t forget the time I “saw” another reproduction of Altamira’s art at the Typhlology Museum in Madrid. Run by ONCE, the Spanish National Organization for the Blind, the museum features, among other things, scale reproductions of national and international monuments that you can touch. This way someone who cannot see the Burgos Cathedral or Statute of Liberty can get some idea of what all the excitement is about.

The reproductions include a carved wood panel that is a scale model of the Altamira ceiling. Beneath my fingers, the figures rose magically from the natural contours of the stone, something hard to fully appreciate just by looking. The artist must have felt the rock and “found” the animals, then rendered them in pigment.

For good reason, the curators of Altamira will never allow anyone to fondle the paintings. While a visit to the real thing might be impressive, its most unrealistic copy helped me understand the paintings in a way that nothing else could.

The real thing might be overrated.

— Sue Burke

Cross-posted from my professional website:

May 7, 2014

Mount Remarkable

April 30, 2014

The HispaCon logo is ready

Spain’s 2014 national convention, the 32nd HispaCon, will take place December 6 to 8. Each year, it’s held at a different site and organized by a different group. This year, the Colectivo Urânik will host it in Montcada i Reixac, a city on the outskirts of Barcelona.

The name of the town gave rise to the initials MIR, and “Mir” or Мир was the name of <a href="http://mount-oregano.livejournal.com/...http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mir" target="_blank">a USSR/Russian space station:</a> this begot “MIRcon” and artwork incorporating science-fictional ideas.

The Colectivo Urânik discribes it as “the space station that orbits in the silence of space, waiting in each corner of the genre, in fantasy, in the dark corners of horror, for all readers who quiver with the love of stories. Our logo welcomes you to a meeting point: the multi-genre space station MIRcon.”

I have plans for December.

More information:

https://www.facebook.com/MIRcon.Uranik

and

https://twitter.com/MIRcon2014

— Sue Burke

April 23, 2014

What’s a “zarzuela” in Spanish?

A zarzuela is a blackberry.

Zarzuela is the name of a small river north of Madrid where there are a lot of blackberry brambles.

Zarzuela Palace, the residence of the royal family of Spain, is located in that area. Originally a hunting lodge built for King Felipe IV in the early 1600s, it was later expanded into a palace.

Starting in the 1600s, Spanish playwrights created a kind of musical theater popular with the royal family. Because they were originally performed at the royal palace, they were called zarzuelas.

These musicals became all the rage in the mid-1800s, and Zarzuela Theater in central Madrid was inaugurated in 1856 to represent them. They were often comedies reflecting working-class Madrid of the day. Since then, the genre has continued to develop and is currently enjoying a revival.

“La verbena de la paloma,” is a classic Madrid zarzuela written by Ricardo de la Vega and Tomás Bretón, first performed in 1894. It is set in the La Paloma Fiesta held every August in Madrid, and the zarzuela has now become part of the fiesta celebrations. You can see a 1995 production of it here: http://youtu.be/c_XNnvmLQ1Q

There is also a recipe from Catalonia, a region in northeastern Spain, called seafood zarzuela, a mixture of fish and shellfish with sauce named after the musical form, which over the years has become a Catalan lyric theater distinct from the Madrid variety.

— Sue Burke

April 18, 2014

Easter: La Saeta, or which Jesus?

Here is a song about that by Joan Manuel Serrat. The words are by Antonio Machado (1875-1939), a poet from Seville, and the poem is La Saeta.

It opens by quoting a popular saeta. These are songs for Easter week processions in Andalucia, in southern Spain. Northern Spain has different songs, but the drums are the same everywhere to mark the pace of penitent funeral processions for Jesus. The saeta asks for a ladder to take the nails from Jesus on the wooden cross. Machado’s poem goes on to lament that this song is always the same, always about Jesus’ death. “... It is the faith of my forefathers. Oh, you are not my song! I cannot sing it, I do not want this Jesus on the wood, I want the one who walked on the sea! ... You are not my song!”

Here is “La Saeta” sung by Joan Manuel Serrat:

Here is a version by Camarón de la Isla (1950-1992), one of the greatest flamenco singers ever:

— Sue Burke

April 16, 2014

Go Ahead — Write This Story: Zero Drafts

Some writers imagine a story perfectly from the start. Others (like me) fumble around before they find their footing. I learned a good way to deal with that: the zero draft. The first try at a story is only an experiment or discovery, and since nothing counts, mistakes don’t matter. For example, I finished a zero draft for a story and at the final sentence realized that I had the point-of-view character’s motivation all wrong. But I’ll get it right on the first draft. This technique works best for people like me who believe rewriting is the key to good writing, so we don’t mind redoing our work.

Whether you use the zero draft method or another means to create your masterpieces, here are a few ideas for stories:

• This is a choose-your-own-adventure story about the discovery of a doorway to the multiverse, and some universes are terrifying or compellingly weird.

• This is a sibling rivalry story in which one travels to the future and sends back sound advice, dire warnings, and lucrative stock tips, but have childhood betrayals really been set aside?

• This is a day in the life of a hobgoblin, which like all its kind is easily annoyed, and the story recounts the practical jokes it considers inflicting before making a final decision.

— Sue Burke

P.S. You can find an expanded version of the post on how to write stories in the form of lists here: http://www.madridwritersclub.com/2014/04/16/6-rules-of-writing-list-stories/

April 9, 2014

Guzmán el Bueno, and how tough it was for him to be “good”

In 1294, the nobleman Alonso Pérez de Guzmán ruled the city of Tarifa, near Cadiz at the southernmost tip of Spain. He received dire news from King Sancho IV that Prince Juan of Castilla, his rebellious brother, was approaching to take the city. The King asked Guzmán to remain loyal.

Juan arrived with Beber and Nasrid troops – and with a page, Guzmán’s oldest son, 10-year-old Pedro.

A siege began, but the mighty walls of Tarifa’s castle held strong – and the King’s reinforcements were on their way. In a desperate move, Juan brought Pedro before his father, who stood at the top of the tower of the castle. If Guzmán did not surrender, Juan said, he would slit his son’s throat.

Legend says that Guzmán replied:

“I did not beget a son to be made use of against my country, but that he should serve her against her foes. Should Don Juan put him to death, he will but confer honor on me, true life on my son, and on himself eternal shame in this world and everlasting wrath after death.”

And, he added, if Juan needed a knife, he could have his. Guzmán threw his knife down from the castle tower.

That reply may be legend, but contemporary reports confirm that Pedro was not only killed, Juan had the boy’s head catapulted into the castle. He and his troop soon retreated.

Among other rewards for his loyalty, King Sancho granted Guzmán the use of “el Bueno” as part of his name, meaning “the Good” or “the Noble.”

This is why, in the subway of Madrid, the stop named “Guzman el Bueno” has knives and castle towers outlined in the tiles paving its platform.

— Sue Burke

Also posted at Amadis of Gaul, an ongoing translation of a Spanish medieval classic.

April 2, 2014

When 1 = 2

She laughed at me, and after a moment I understood why. I was in Texas, but I live in Spain. In the United States (and most of Canada), B 1 2 means “Basement, 1st Floor (Ground Floor), 2nd Floor.” In Spain (and most of Europe) B 1 2 means “Bajo (Lower or Ground or 0 Floor), 1st Floor, 2nd Floor.”

In other words, what is called the 2nd Floor in the United States is the 1st Floor in Spain. I had only one choice going up, and that was 2, because we were already at 1, the ground floor.

This is a detail to bear in mind when translating. For example, in early February, a huge storm hit Spain’s north Atlantic coast, delivering 7-story-high waves – or at least that’s how they were described in Spain. But if I were going to tell someone in the United States about it, I would have to say they were 8 stories high, especially in Texas where everything is bigger. (You can see spectacular photos here.)

There are other details of language and culture to bear in mind, for example:

• Billion means 1,000,000,000 or a thousand million in the United States (and some other countries) and 1,000,000,000,000 or a million million in Spain (and some other countries). This often causes problems.

• Some countries, including Spain, use a comma to indicate decimals, so 1,234 might equal 1.234: a quantity a bit smaller than one and one-quarter. Reciprocally, 1.234 in Spain (and some other countries) equals 1,234, or one thousand two hundred thirty-four. There’s a big difference.

• In Spain, morning is the time period that lasts from getting up until the main meal is eaten at about 2 p.m., so it is still “morning” after noon. Also, television prime time (horario central) in Spain starts at 10 p.m.

• The expression fifteen days in Spanish means two weeks, or “fortnight” if you’re British.

• Payment for work, such as minimum wage, is expressed by a monthly rate in Spain (and some other countries), not hourly.

So if you ever compare a translation to the original and numbers look different, they may still be the same. The translator may have had to do a little math. It’s part of the job.

— Sue Burke

Also posted at my professional writing website,

March 24, 2014

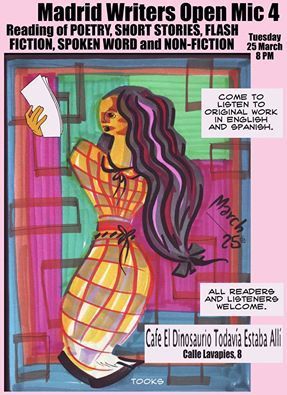

Madrid Writers Open Mic 4

Come read or listen to poetry, short stories, flash fiction, spoken word, and non-fiction at the Madrid Writers Open Mic 4: Tuesday, March 25, 8 p.m., at the Café El Dinosaurio Todavía Estaba Allí, calle Lavapies 8.

The readings will be in English and Spanish. Four minute limit. More information here:

https://www.facebook.com/events/214465562083139/

I’ll be reading a sonnet.

— Sue Burke