Sue Burke's Blog, page 19

July 13, 2022

A portal fantasy right here and now

I’ve found a portal to another dimension in my apartment building: the missing 13th floor.

You scoff. Lots of buildings don’t have 13th floors, you say. Otis Elevator has explained that it’s not a plot, just a preference. “Due to the superstition associated with the number 13, the unlucky number is often omitted from elevator panels and stairwells.”

I say that’s what they want you to think. Or maybe Otis really believes this because the corporation operates exclusively in our quotidian dimension and doesn’t have all the facts.

True, though, it’s not just this building. The “13th” dimension exists as a horizontal layer across the landscape from building to building. It’s vertical, too. Like many buildings, mine has no 13th apartment units. The numbering goes …1410, 1411, 1412, 1414, 1415…

So, what’s in the 13th dimension? It could be a fantasyland with fairies, elves, unicorns, and the like, living and working in apartments, offices, and hotel rooms, possibly rent-free. The dimension could function as time travel, taking us to the year each building was built. It could be the hub for a physical shortcut, letting us jump from a building in Chicago to a building in New York by opening the right door. Or perhaps something nefarious is operating on the 13th floor…

Think about that when you get on an elevator. Better yet, think about that when you get off. Be sure it’s the floor you want. If you’re looking for the 13th floor, come prepared.

Where will it take you?

July 6, 2022

How much of a tree is alive?

Photo by Sue Burke

Photo by Sue Burke“How much of a tree is alive? Certainly not the outer bark. That falls off in dry scales, or can be scraped off down to the white layers within, and the tree be none the worse. Certainly not the wood. One often comes across old trees that have lost limbs or been carelessly pruned, which are entirely decayed out on the inside, so that nothing is left but a thin shell next the bark. Yet these trees grow as vigorously as ever, and bear leaves and fruit like a solid tree. The bark is dead; and the wood is dead. Between the two is a thin layer, perhaps a quarter inch through, which is alive. On one side, it is changing into dead wood. On the other side, it is changing into dead bark. The new wood is alive, and the new bark. Between them is something neither wood nor bark, but just living tree-stuff. The green leaves also are alive, and the green twigs, and the blossoms, and the growing buds. But at least half of every living tree is already dead; while the larger and longer lived a tree is, the smaller proportion of it is alive at one time.”

— from Natural Wonders Every Child Should Know by Edwin Tenney Brewster, physicist and popular science writer (October 11, 1866 – March 14, 1960). More information and links to download the book are here.

June 29, 2022

My Goodreads review of “Roadside Picnic”

Roadside Picnic by Arkady Strugatsky

Roadside Picnic by Arkady StrugatskyMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

Space aliens suddenly appear at six different places on Earth, stay a little while, then go away, paying no attention at all to humanity. They leave behind apparent trash, the way careless picnickers might stop alongside the road, eat lunch, and then depart, leaving behind trash that would mystify the squirrels and ants, and some of it might be toxic.

Thirteen years later, in one of those places, a city called Harmont, scientists are trying to understand what was left behind, and “stalkers” are trying to smuggle out everything they can because there’s a profitable market for the trash. Organized crime slowly edges out science, even though some of the trash is terrifyingly toxic.

As a first contact novel, Roadside Picnic takes an uncommon approach. We humans can’t understand the aliens, and they might not be interested in us anyway. We can only react — and we react in the way we always have to any novel situation. In this case, in the city of Harmont, a corrupt society grows more corrupt, but not without sufficient self-awareness to understand and debate why it is heading down that violent, destructive road.

My only quibble is that the novel focuses relentlessly on Harmont with no clue about what is happening at the other sites. Were there other kinds of responses? I think the addition might have added depth, but the novel is plenty visceral and fascinating as it is, a deserved classic in science fiction.

View all my reviews

June 19, 2022

A useless old key that I won’t throw away

Decluttering may be good for you, but I have something useless, stored away in a box and half-forgotten, and I will never throw it away: the key to my late parents’ old home. They left that house twenty-five years ago.

That house … They loved living there, a small ranch home at the end of a cul-de-sac. They enjoyed its wide windows, airy sun porch, and large back yard. My mother planted a flower garden in front and a vegetable garden in back, and together they worked hard to create a charming, comfortable interior. On weekends they would visit nearby parks, go to sporting events, or simply relax at home. They were happy there.

I lived in a nearby city, and I had the key because I could come anytime — always welcome, just walk right in — and I came when I could for holidays and visits.

My parents have died, someone else lives in that house, and I’ll never go back. Someone else might think that an old key is useless, but they never used it to walk into that happy home.

Once, that key opened a door. Now it opens memories.

June 12, 2022

Ludlow Charlington’s Doghouse: an anthology supporting Friends of Chicago Animal Care and Control

If you’re in Chicago, come to the preview reading Tuesday, June 14, 7 p.m., at Fado Irish Pub and Restaurant, 100 W. Grand Ave., near the Magnificent Mile downtown! More information here: Ludlow Charlington @ GFS 6/14/22 | Facebook

Each year, the City of Chicago Animal Care and Control gets thousands of unwanted animals. Some are pets whose owners can no longer keep them, some are strays, and a few are evidence animals in court cases. Most of these pets are looking for homes, and all of them need care.

That’s what Friends of Chicago Animal Care and Control does: its members help Chicago’s neediest animals.

At Ludlow Charlingtons Coffee Shop in Chicago, eleven ornate portraits of contemporary dogs dressed in historical costumes hang on the walls. As a fundraiser for FCACC, nineteen writers, mostly from Chicago, have donated work to an anthology based on those portraits.

In all, thirty-four stories, poems, and plays tell about guarding kids, dealing with queens and kings, captaining a pirate ship, and creating a fashion trend. They span the globe and historical eras. I wrote a sonnet about Dog Six.

You can buy the Ludlow Charlington’s Doghouse starting June 14 for only $5.99:

June 8, 2022

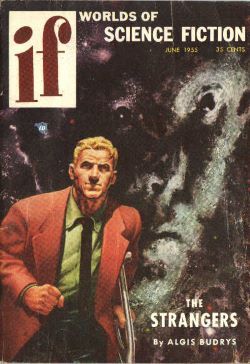

Science fiction when I was born: a review of IF Magazine from June 1955

What was science fiction like when I was born? I got a copy of the June 1955 issue of IF: Worlds of Science Fiction at a Science Fiction Outreach Project giveaway. The digest-sized pulp magazine was yellowed, and the pages included a scribbled phone number and some crumbs, but otherwise it was in great condition.

You can read this magazine online at the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/1955-06_IF

Here’s what I thought of the stories.

“The Strangers,” a novelette by Algis Budrys

A young man, Spencer, is celebrating his twenty-fourth birthday by getting drunk and regretting his failed life, when a mysterious stranger sits next to him and says that Spencer’s former mysterious benefactor has died. This benefactor had, since childhood, set Spencer up “to be something more than a man” until an injury shattered the young man’s hip and left him “half a man.” (I’ll refrain from commenting on the ableism.)

After a series of further encounters that might not be accidental, Spencer comes to understand that non-physical entities from another universe were trapped on Earth long ago and have been using Earth life forms, especially human beings, as chrysalises of a sort to wait out the chance to leave. Spencer discovers he has a superhuman mind and can send the aliens home, so he does.

Overall, it’s not a bad story or badly written, but there are plot holes and a deus ex machina ending. A cool idea didn’t get its due.

The cover art of the magazine, by Frank Kelly Freas, apparently depicts the main character of this story. Note the crutch. However, the story explicitly says the character is 24 years old. The art seems to be of an older man.

Another work by Algys Budrys that I’ve read is the novel Rogue Moon, and I was not impressed. My Goodreads review gives it two stars.

“Bright Islands,” short story by Frank Riley

In the recent past (relative to 1955), a young woman is being used by the Nazi government to breed a child with superpowers. She’s about to give birth, but she’s stolen a poison pill. Should she take it? This simple narrative runs deep with distilled emotions, probably even more intense in 1955, ten years after the end of World War II. Well done.

You can read “Bright Islands” as a free ebook at Project Gutenberg.

“Your Time Is Up,” short story by Walt Sheldon

“What year? It’s 1955, of course.”

“Why,” he said, “this is remarkable!”

“It is?”

“Do you know what I think has happened? A quantum inversion.”

The story involves a change to the Pentagon telephone system that accidentally allows a colonel to call someone in the far future who explains that there will be a Final War… I could guess the twist well before the ending, but the lively narration kept me entertained anyway. I was a little flummoxed by the primitive telephone system, though. Live operators? They were gone by the time I was old enough to use a phone.

“Men of the Ocean,” a novelette by R. E. Banks

A portion of the ocean floor has been used for mines and kelp farms for half a century, keeping the land and sky fed. But the world has changed, and now there’s a complicated, murderous plot to get the title to that land on the ocean floor. With sharply drawn characters, an inventive narrative with lots of twists and solid pacing, this is one of the better stories in the magazine. I think I’m an R. E. Banks fan now.

Of course, there are the occasional anachronisms, like pay phones and important documents available only as a single paper copy, but that’s forgivable. It’s one thing to imagine an automated mine. Imagining mobile phones and automated e-ticket systems might have been too much back then.

“Until Life Do Us Part,” short story by Winston Marks

On one level, it’s a story about two men fighting over a woman, and one of them kills the other. (I’ll refrain from commenting on the sexism.) The story tries, however, to explore the idea of immortality. “It’s a long life … the price of immortality is caution, patience, temperance…” but “if there was one activity that immortal, 28th Century Man could no longer afford, it was the luxury of falling in love.” The story lightly skims the surface of an interesting idea.

“The Twilight Years,” a short story by Kirk and Garen Drussai

An over-60 couple gets very anxious at sundown, and the reason turns out to be terrifying: young people resent old folks for having “outlived their usefulness … especially if we are a burden and there are too many of us.” The story also anticipates live reality television, and the couple are hunted down and killed as they watch it happen in their own living room. It’s chilling, but shallow characterization undermines the premise.

“Freeway,” a short story by Bryce Walton

Opening paragraph: “Some people had disagreed with him. They were influential people. He was put on the road.”

A man has been condemned to drive endlessly with his wife up and down the highways of the United States. “There were thousands now on the Freeways, none of them had any real criminal labels. They were risks. They might be dangerous.” He can’t get off the road. The man’s wife is being driven mad by this punishment, and he’s trying to find her help, but no one wants to help people like them.

[Spoiler!] The man is a danger because he taught nuclear physics at a university. “You taught other guys how to build hellbombs.” In his search for help, he finds an escape from the road to join a secret village of other condemned intellectuals. “So we’re off there waiting now. Waiting and studying. Someday they’ll need us again. And we’ll be ready.”

Bryce Walton apparently wrote prolifically for the SF pulps. If all his short stories are as good as this one, he should not be forgotten.

“Forced Move,” a short story by Henry Lee

Earth and invaders from outer space are locked in an unwinnable conflict, but one man knows the winning maneuver — if he can find a way to get into the Pentagon to carry it out, and getting in may cost him his life. His gambit forces the invaders to make a fatal mistake, although the Earth forces suffer tremendous losses. Still, the long stalemate is over.

As far as I can tell, this is the only fiction Henry Lee ever published. Too bad. From the first sentence to the last, the tension holds steady. Or maybe this is a pen name for another author who already has a story in the issue, a common practice at the time. Pulps paid the bills, and some writers were prolific.

“Pioneers,” a short story by Basil Wells

A small but determined group of people have left Earth to travel to Sulle II, an uninhabited, Earthlike planet, to homestead and send food back home. Despite jealousies and hardships, they survive, build cabins, and hunt and farm. One woman seems to be driven insane by the loneliness and runs off, and the pursuit reveals [spoiler!] that they’re still on Earth, far from the domed cities where most people live.

At times, the story depends on what feels like manufactured conflict to me, but the shocking reversal is well hidden.

***

Overall, how does it compare to SF stories today? The technology, of course, reflects the 1955 imagination of what the future would be like. Some of that imagination is impressive, if odd, compared to what actually happened.

The big difference lies in another kind of imagination. With one small exception, everyone in the stories is white, and the protagonists are men. Women are wives, girlfriends, and mothers — they exist only in their relationships to men. All but one story takes place in the United States.

The world is a bigger place now than it was when I was born … the world that we write about, that is. Now we tell stories about more kinds of people and places, and those people can do more in their lives. Back in 1955, science fiction could not anticipate that kind of future, wider and more free.

June 1, 2022

My Goodreads review of “Hard to Be a God” by the Strugatsky brothers

Hard to Be a God by Arkady Strugatsky

Hard to Be a God by Arkady StrugatskyMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Written in 1963 in the Soviet Union, this novel reflects the politics of its time and place. Arkady and Boris Strugatsky were appalled by their government’s vicious rebuke of artistic freedom after the brief thaw in Stalinism. They say in the Afterword to my edition, “We weren’t as much afraid as disgusted…. We were being governed by goons and enemies of culture…. They will never let us say what we believe is right.”

At that point, they changed their plans for the novel they were working on. They had meant to write a swashbuckling adventure story set at the twilight of the Middle Ages. Instead they wrote about the fate of intelligentsia. A historian, sent from Earth to a distant planet to impersonate a minor aristocrat, observes its medieval-like society as if he were a god — initially with the vague hope of rescuing it.

The historian, Rumata, has a lot of swashbuckling adventures with other drunken aristocrats as the society around him collapses. Scientists, writers, and poets are rounded up and killed by religious fanatics and lazy, cruel overlords, and finally Rumata sees no way to stop the disaster. Could a god enlighten the cruel princes? He doubts it. “Cruelty is power. Having lost their cruelty, the princes would lose their power, and other cruel men would replace them.”

Soon, he realizes that “he was no longer playing the role of a highborn boor but had largely become one…. Does a god have the right to feel anything other than pity?” As blood pools in the landscape around him, he asks himself again and again, “What could we have done?”

Although this sounds bleak, it’s not a chore to read. Action, escapades, and humor fill the novel.

In our own time, Russia seems to be ruled again by “power-hungry dullards and blockheads.” Other countries face tough political choices, including my own, the United States. The strange, Russian, historic feel of this novel now has renewed resonance.

View all my reviews

May 25, 2022

Four years ago, I started writing “Immunity Index” and made mistakes

Back in March 2018, I made two mistakes when I started writing the novel Immunity Index.

The first mistake was to try “pantsing” as a writing technique — that is, to write from the seat of my pants rather than from a plan and an outline. While my first drafts are always shit (which does not make me at all like Hemingway in any other sense), this first draft was especially bad and required nine painful complete rewrites.

The second mistake was trying to tell a story set in the near future. Events in the future, like the things seen in a convex mirror, are closer than they appear.

This vision of the future, however, started back in the 1980s. As a newspaper reporter, I was covering news about AIDS, then a terrifying new disease. One evening, before a meeting, I was chatting with the Wisconsin state epidemiologist. He said that as bad as AIDS was, it could have been worse. He was a gay man, and we both knew that AIDS was already a disaster, and the disaster would keep growing.

He said, though, we were lucky that AIDS was only communicable, not actually contagious. Worse would have been a fatal illness that could be spread as easily as a cold.…

In 2018, I imagined a deadly, contagious coronavirus. It was fiction. Until it wasn’t.

My fictional story, though, is better than our shared reality. For one thing, the novel has a happy ending — and it has suspense, intrigue, adventure, and a woolly mammoth.

Immunity Index — now available as a trade paperback, hardcover, ebook, and audiobook. Find your favorite retailer here.

May 18, 2022

My choice for the Nebula Award for Novella

As a member of SFWA, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, I can vote for the Nebula Awards. Usually I focus on the shorter works — short stories, novelettes, and novellas — due to time constraints and because these categories tend to attract fewer voters, so my vote matters more.

The 57th Annual Nebula Awards will be presented on May 21 during the Nebula Conference Online. Although the conference is for paid attendees, the award presentation will be live-streamed.

A novella, according to the Nebula rules, is at least 17,500 words but fewer than 40,000 words — a short novel. Some consider it the ideal length for speculative fiction, long enough to create a world but short enough to allow for unrelenting tension or unusual storytelling techniques. Here’s a brief evaluation of each finalist, ending with my choice, but I thoroughly enjoyed each one.

Flowers for the Sea by Zin E. Rocklyn (Tordotcom) – A woman gives birth to a monster in a monstrous world. Lyrical, visceral, nightmarish.

Sun-Daughters, Sea-Daughters by Aimee Ogden (Tordotcom) – Two old frenemies face off in a fully imagined fantasy setting. However, the ending feels more like a first chapter than a novella because problems are deepened rather than resolved.

Fireheart Tiger by Aliette de Bodard (Tordotcom) – Two princesses form part of a danger-filled love triangle. It illustrates what I think is the hallmark of Aliette de Bodard’s work: impeccable storytelling.

“The Giants of the Violet Sea” by Eugenia Triantafyllou (Uncanny 9–10/21) – A young woman in a hardscrabble colony on a distant planet must confront a frayed family, repeated betrayal, and venom. Beautifully told.

The Necessity of Stars by E. Catherine Tobler (Neon Hemlock) – A diplomat, suffering from debilitating mental and physical decline, must face both an alien attack and a deteriorating world. Lush prose, although the story seems to insist that the woman’s troubles are routine for age 63.

A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers (Tordotcom) – A lost monk in a solarpunk-style world finds themself, or maybe they get found. Humane and uplifting, as we would expect from Becky Chambers.

And What Can We Offer You Tonight by Premee Mohamed (Neon Hemlock) – A murder victim in a brutal world seeks justice — to say more about this lyrical piece would be a spoiler. The tension never ebbs, the language is poetic, the voice is outstanding, and the characters glow with life. I loved this story and A Psalm for the Wild-Built equally, but the poetry and voice in Premee Mohamed’s work was the feather that tipped the scales.

May 12, 2022

Reading at Strong Women Strange Worlds on May 19

I’ll be reading from my novel Immunity Index on May 19 as part of the Strong Women Strange Worlds series. The Zoom presentation is at 7 p.m. ET. Sign up to attend at https://strongwomenstrangeworlds.weebly.com. Other readers are Heather Rose Jones, Missy Jane, Kyoko M, Cass Morris, and Mari Ness.

The novel Immunity Index is now available in trade paperback, hardcover, ebook, and audio book editions. Find your favorite retailer here.

“Prescient and powerful, this is a gut-punch of a book.” — Seanan McGuire