Jennifer Cody Epstein's Blog, page 7

April 2, 2013

The Beach

I first registered the fact that my daughter would one day leave me when she was still really a baby.

Katie had never crawled. But by around eighteen months she could not only walk but could put on her own clothes—swimsuits included. This she did one wintery evening, emerging from her room in a pink, tutu-style one-piece she’d apparently found in her drawer. After shrugging a raincoat over it and tugging on rainboots, she marched purposefully to the door.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

“Beach,” she replied, and reached for the doorknob.

My husband and I exchanged glances. It was a freezing February night. The nearest beach was two hours away by car. I didn’t know how she figured to get there on her own, but it was clear she wasn’t giving up easily.

“We can’t go to the beach right now,” I said. “It’s night-time. And cold.”

“BEACH,” she repeated, rattling the doorknob.

“The beach is closed now,” my husband offered. “There’s no one there. And there’s snow on the sand.”

“Beach! Beach! Beach!” Katie chanted, and proceeded to pound on the door itself. Soon she was hurling herself at it, red-faced and tearful, devastated by this failed attempt at self-determination. As I scooped her up I found myself teary-eyed too—and not just due to suppressed laughter. As I carried her to the bathroom (“We’ll make a beach here,” I told her) I also felt a shiver of prescience. Up to that point, Katie’s life had been almost indistinguishable from my own: we woke and slept together; came and left together. There was rarely a moment when we weren’t somehow connected, and I’d come to take that connection for granted.

But watching her fight so hard to leave that night made me understand something I really hadn’t before: that one day, my daughter would don her swimsuit, put her hand on the doorknob, and open that big wooden door with ease. Hey, Mom! I’m going to the beach.

And slam—just like that, she’d be gone.

The image caught in my throat, achingly sweet but painful, too. It was a feeling I’d have often in the years to come: dropping an outgrown dress into the Donations pile. Passing the playground that–at some point when I wasn’t paying attention–we somehow stopped going to play in. Sending Katie to school alone, armed only with a cell phone and attitude (of which thankfully she still has a lot).

I felt it again the other night as I put her to bed. Now twelve, she looked up at me a little sadly.

“I wish,” she said, “I could be little again. Do you wish that, Mommy?”

“Yes,” I said, hugging her. And then: “No.”

“Well, which is it?” she laughed.

I hesitated for a moment, thinking. “Both,” I told her finally. “It’s contradictory.”

For that, I’ve come to realize, is what parenthood really is: a lifelong, life-affirming dance of oppositional moments: clinging and cleaving; rejoicing and grieving. Putting on your swimsuit, and leaving. Or maybe just banging on the door, secretly relieved that — this time, at least –it won’t open to let you out.

(Note: This piece will be appearing in the Girls Write Now 2012-2013 Anthology, alongside a beautiful piece by my mentee there, Emily Ramirez.)

March 30, 2013

On The Windfalls of Failure

When I was 27 years old, the life I’d carefully constructed for myself fell almost spectacularly apart.

I was a foreign correspondent for a major publication, and by all accounts it was a dream job: six-figure salary, ex-pat benefits, a hefty expense account. The satisfaction of knowing my byline was read by thousands. When I told people what I did for a living and where I did it, I got impressed nods and verbal kudos: “You must be a good writer,” they’d say. I’d smile modestly. I was a good writer–that much I knew. But these exchanges confirmed much more than that for me: that I was a fast-tracker; a go-getter. Someone aiming high, and getting there. In short, everything I’d ever hoped to do and be.

Then, one day, it all tumbled down. Called into my bureau chief’s office, I sat down with my pen and notepad, expecting to be given my next assignment. Instead, I was given marching orders. “I don’t know how to say this,” he said, “so I’ll just go ahead and say it. We’ve decided to let you go.”

He hesitated a moment. Then—meaning (I’m sure) to be kind, he added: “I don’t know what your calling in life is going to be. But I’m pretty sure that it’s not going to be in journalism.”

In the silence that followed I heard the crash and tinkle of my entire existence, shattering. We went through the next steps—my severance package; planning a month-long exit frame which would include training my replacement. It all seemed hazy and gray. The one thought I had with startling clarity was this: “It’s happening. The worst thing that’s happened to me in my life. It’s happening now.”

As I walked out of the building that afternoon, each step felt like a freefall. Normally I’d spend my lunch hour reading up on news or re-drafting a story, but none of that made any sense now that I no longer had a job to do. I’d been flung off the fast track. I was no longer a correspondent. It seemed possible that I wasn’t even a good writer after all–that my life’s passion, and the one talent I’d never doubted in myself amounted to no more than “beginner’s luck.”

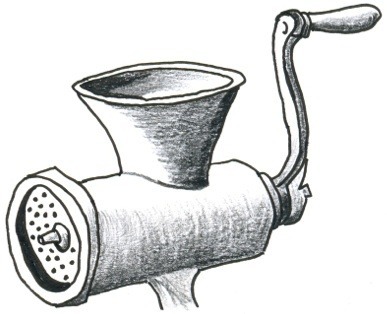

After wandering for a while I finally called my parents from a payphone, even though it was three a.m. in the U.S. My father listened quietly as I choked out my story. Then he said something I still remember often: “You’ve been chewed up and spit out by life’s meat-grinder. It’s not the first time it will happen to you. And in ten or fifteen years, this won’t even seem like a big deal.”

In the bleak weeks that followed, this prediction seemed hard to believe. Even as I applied for and was quickly offered three exciting new jobs in writing (one of them with the same publication, but the television arm of it), I couldn’t escape the sense that my failure wasn’t just that—a failure—but a crushing confirmation of all my inadequacies, both professional and personal alike. In my head, I lived and re-lived the curt half-hour of my demise, analyzing every moment, every keystroke that had led up to it. Going over and over that tactless, point-blank condemnation: I don’t know what your life’s calling is going to be. But I’m pretty sure it’s not going to be in journalism. In my new city, at my new job, I compared myself to my new work colleagues and felt like a fraud. I was certain I’d never succeed at anything again.

And yet in those rare moments when I was really honest with myself, there was also a sheepish sense of relief. The truth was, while I’d worked hard to get to the high place from which I’d fallen–graduating magna-cum-laude from an elite college where I was one of the paper’s editors; cutting my teeth at a fast-paced international wire service; obtaining a fancy Masters in International Affairs with a specialty in economics—there had also been a growing sense that this “dream job” was from someone else’s dream. It was a feeling I’d had even on the plane flight back from my final interview for The Big Job, when it hit me that they were going to make me an offer. A big one. I should have been elated. Instead, I was just anxious—as though I were stepping onto an express train headed away from my desired destination. And in retrospect, that was exactly what I was doing.

Here’s the thing I hadn’t let myself admit–not to my interviewers, not to my parents, not even to myself: I’d never had a burning desire to be a journalist. My first love has always been fiction, and what I’ve always wanted most of all was to write it. Nonfiction has simply never spoken to me in the same way. What it did do was offer security, a clearer path to what most people can comfortably call “success.” Which, of course, was precisely why I chose it–or (as it now seems in retrospect) let it choose me. But even in the midst of it my most exciting professional moments, I never really looked forward to my job in those days–at least, not as much as I looked forward to my long commute to and from it. My colleagues used the time to pore through news stories, which is probably what I should have been doing too. Instead, I lost myself in Graham Greene and A.S. Byatt and Michael Ondaatje, because those were the stories that really moved me. And in the months prior to being fired I’d been quietly but increasingly unhappy; feeling unable to engage with the material I was writing, and unable to connect with my colleagues who could. I’d even fantasized about quitting the Big Job, moving back in with my parents and trying to flesh out an idea for a novel

Of course, I never could have actually done that. For one thing, they were (understandably) appalled when I half-jokingly gave voice to the idea. Besides, who voluntarily leaves a dream job?

Still, as I made my way through the next four years in television, then into grad school and (simultaneously) into my marriage, I came to realize that having the “worst thing” happen to you can sometimes be the best thing you can hope for. Without failing, I’d almost certainly have kept plugging along in a career that never really suited or satisfied me– a fate far worse than being served the odd pink slip. More importantly, I would never have had an excuse to discover both my true talent and my true dream job—weaving research and narrative into historical novels, which in turn speak to fellow fiction-lovers across the world–maybe even on their commutes.

So in the end, my bureau chief turned out to be right: my life’s calling wasn’t in journalism. My dad was right as well: I’d indeed been chewed up and spit out by life’s meat-grinder, and it wasn’t the first time it would happen. Not by a long shot. He was wrong about one thing, though: nearly twenty years on that failure still seems like a very big deal. It was the reason I met my husband, moved to Brooklyn, left journalism for an MFA, and started a family I adore. It was the reason I wrote and published my first novel, and more recently my second, and am both engaged in my work and eager to get to it each day. In short, it was catalyst that propelled me—albeit kicking and screaming–into the life I was probably really meant for.

I can only hope my next failure brings with it such a windfall.

Vogue (From April’s “Hit List” of Highly Anticipated Fiction)

“The Gods of Heavenly Punishment showcases war’s bitter ironies…as well as its romantic serendipities.”

March 25, 2013

“Gods”: The Rumpus Interview

I was thrilled and honored to be the subject of a very thought-provoking interview with the awesome lit blog The Rumpus, courtesy of fellow historical novelist Padma Viswanathan (who wrote The Toss of a Lemon, which is easily one of my favorite historical novels ever). Padma had some very smart questions to ask, ones that really had me pondering on why, exactly, I wrote The Gods of Heavenly Punishment and what questions I was trying to ask and (perhaps?) answer. Here’s one of the ones I found particularly interesting:

I was thrilled and honored to be the subject of a very thought-provoking interview with the awesome lit blog The Rumpus, courtesy of fellow historical novelist Padma Viswanathan (who wrote The Toss of a Lemon, which is easily one of my favorite historical novels ever). Padma had some very smart questions to ask, ones that really had me pondering on why, exactly, I wrote The Gods of Heavenly Punishment and what questions I was trying to ask and (perhaps?) answer. Here’s one of the ones I found particularly interesting:

PV: This is a huge question, but please bear with me, and correct my understanding if you think I’ve gotten it wrong: How did you come to feel about the moral balances in the book, as conveyed through your characters? In particular, how did your understanding of the faults and decisions on each side evolve as you worked on the book? While we see the damage inflicted by the American bombs Cam drops, this role of his was official, whereas the Japanese who take him prisoner are in violation of Geneva Conventions. It obviously is wrong to bomb civilians, but that particular ill is still widespread, and wasn’t, I think, outlawed until post-WWII. In other words, the Japanese come across as brutal and benighted by our standards. No American is shown committing war crimes. Individual racism seems about equal on both sides. The spoils of Japanese-American homes evacuated by internment are used to furnish Anton’s model home, but that’s about all we get of systemic American wrongdoing, and it’s not illegal. What I took away was that, even despite the horror of the firebombing, the Japanese had to be stopped, much as the Nazis did. To portray Nazis as evil is something we take for granted, however, while showing the Japanese, or their military, that way must have been tougher, I imagine, not least because of the vexed question of race, and because of the nuclear bombings. Am I way off course?

JCE: Not at all. Those are actually the types of things I asked myself many times as I worked my way through the book, and finding objective answers to them was elusive, to say the least. In fact, I really can’t pretend to have done that—only to have explored the questions.

For me, part of that exploration involved questioning what we mean when we use terms like “evil” and “crime.” Defining either can be a murky task, but is especially so in wartime. I think, for instance, that it’s dangerous to use a blanket label like “evil” when thinking about an enemy–even in as egregious an example as the Nazis. In doing so, you risk distancing yourself to the point of losing sight of the potential universality of what happened in Germany. Yes, there were men in charge who were clearly monsters. But the greater problem was the German population–millions of Germans who considered themselves decent, moral human beings, who ended up following the Nazi agenda. They followed it not because they were intrinsically “evil,” but because they allowed themselves—be it through action or apathy–to be steered by national policies that carried sickening moral and human consequences. In the end that’s what the Japanese did as well, albeit on a different scale and to a different populace—so if you’re going to argue that one is “evil” you probably need to argue it for both, regardless of race or eventual fate. But in my opinion, what’s truly important to remember is just how easily—even casually—that evil occurred. And that it can occur again any time, in any nation (ours included), and at the hands of people who in all other respects are just like the rest of us.

Likewise, “crime” can become a very slippery term—particularly when it comes to air power (as the ongoing debate over its next phase—e.g. drones—attests to). My sense of the fire bombings, both in Germany and in Japan, was less that they were considered “legal” or “illegal” than that there was no clear legal framework yet established for them. The U.S. military essentially made up both the technology and the rules as it went, and by that point no one was going to stop them. And as Max Hastings writes in Retribution, the decision to “bomb and burn ‘em till they quit” really came down to a small handful of military leaders, with no weigh-in on the presidential level, and certainly no commentary from the U.K., which had long been doing blanket area bombing in Germany (a fact which, incidentally, I think partially addresses the “vexed race” question).

Those orchestrating the bombings acknowledged that civilians would be killed, but tried to balance it out morally by noting that Japan’s war industry was both small-scale and deeply enmeshed with the city’s residential neighborhoods. “The entire population got into the act and worked to make those airplanes or munitions of war,” Curtis LeMay asserted later. “We knew we were going to kill a lot of women and kids when we burned that town. Had to be done.” As Hastings also points out, he and the other architects of the bombings conveniently overlooked the fact that the U.S. Naval Blockade had already effectively strangled Japan’s military industrial complex by 1945.

To be sure, LeMay’s seeming casualness about the hellfire he unleashed doesn’t obviate the fact that the Japanese, like the Germans, were clear aggressors in World War II, and clearly did need to be stopped. Nor does it change the fact that, unlike the Germans, an entire Japanese generation had been raised to see death as the preferable alternative to defeat—and was prepared to fight to the very last man, woman or child. There is little question that more American lives and many more Japanese lives would have been lost in a land invasion than were lost in America’s air campaign, however brutal it was.

Curtis LeMay

There is, however, a very large question for me when it comes to the extent and execution of that campaign. Whatever they might have said publically, LeMay and his colleagues knew full well that in firebombing all sixty-seven of Japan’s major cities, they were sentencing hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians to horrific deaths–for the sake of a military objective that was at best negligible. They also knew—from experiences like the London Blitz—that traditional area bombing can just as easily boost enemy moral as crush it. So the looming issue becomes less one of whether it was “legal” than whether it was worth the human and moral cost—especially given that, unlike the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there is no obvious evidence that the firebombings brought Japan any closer to surrendering.

That also isn’t a question I can or even seek to answer in my book. But I think it’s one that needs to be considered.

To read the whole interview (plus a lot of other really cool lit stuff) go to TheRumpus.net.