Jennifer Cody Epstein's Blog, page 6

May 1, 2013

Publishers Weekly

“Epstein’s second novel (after The Painter from Shanghai) is bursting with characters and locales. Yet painful, authentic (Epstein has lived and worked in Asia), and exquisite portraits emerge of the personal impact of national conflicts—and how sometimes those conflicts can be bridged by human connections.”

April 30, 2013

Kirkus Reviews

“An epic novel about a young Japanese girl during World War II underscores the far-reaching impact that the decisions of others can have.”

April 26, 2013

How An Act of Incest Changed The Way I Write

When asked about who or what I find inspiring as a writer, I tend to find myself floundering. An obsessive reader who consumes three or four novels at a time, the term “inspiration” evokes not one source for me, but a whole tide of them; fluid and intermingled, perpetually fed by the towering piles on my nightstand and the various voice that stay afloat in my memory. Separating out those voices is like tracing which Pacific Ocean currents come from the Strait of Malacca–versus, say, from the Yellow Sea.

Recently, however, I had a sort of epiphany. I was being interviewed about my latest book, and in particular about a character in it who does a pretty horrible thing. This man, my interviewer said, had “completely repulsed” her. Yet in the end she found she had sympathy and even affection for him. “Did you intend for him to be all that at once—both empathetic and monstrous?” she asked. “What inspired you to write him that way?”

Unexpectedly, I found myself shooting through one of those weird wormholes of memory, and landing decades earlier on my long-gone childhood bed. In my lap was a novel, and in last pages of this novel, on a cold kitchen floor, a father rapes his pubescent daughter. As I finished the scene I was weeping–but not (just then) for the girl. My overriding grief was actually for the father, and this mystified me. I read the section twice and then a third time. I studied its seams and its wording, trying to comprehend how one performed such literary alchemy; transforming a truly reprehensible crime into an act of tenderness, and almost love.

The author was Toni Morrison, the book was The Bluest Eye and the rapist was Cholly Breedlove, the unemployed, alcoholic and fatherless father of 11-year-old Pecola Breedlove. In the pages prior to the fateful moment Morrison had intertwined Cholly’s narrative with those of others in his world, employing language so precise and subtle that it read like one long poem. In the process, she had crafted a devastating portrait of an impoverished family in Ohio that is trapped by race and era. Even more powerful for me, though, was the depiction of Cholly’s heartrending moral descent. It’s unthinkable; monstrous; inhuman. And yet Morrison refuses to let us dismiss it as any of those things. Instead she makes us think about it, forcing us to see the flip-side of inhumanity as humanity, the foundation of monster as man and the potentiality of evil in all of us. In essence, she showed me—a white twenty-year-old from a wealthy New England suburb–the lurking Cholly within myself.

It was a scene that had prompted numerous attempts to ban The Bluest Eye from schools and libraries 1970 publication. For me, though, in the summer of 1985 it sparked a very different response. I knew I’d never look at a “monstrous” act in quite the same way. And in the years since I can honestly say I haven’t; reading the paper or a history text or even another novel I still sometimes feel Cholly Breedlove’s haunting presence. But it also made me think: Yes. This is the point of fiction: finding those rare flashes of insight; those perfect (if sometimes painful) moments of human connection. It made me want to read every word Toni Morrison had ever written. And it made me want to write like her—even if just a little.

Back in the present again I said none of this to my interviewer, though I’ll admit I suppressed a tiny thrill at the question. In answer, though, I simply said: “My inspiration? I’d say Toni Morrison. And in particular her first novel, The Bluest Eye.”

*Note: This piece appeared originally on the blog Bookriot.com.

April 24, 2013

On That Pesky Line between History and Fiction

One of the most frequent questions I get as a historical novelist is: “How much of what you write is really history?”

It’s a good question. And an important one, I think–especially given how discomfort-making the blending of fact and fiction can be. It’s sort of the literary version of mixing beer and liquor: for some people, even the idea makes them queasy.

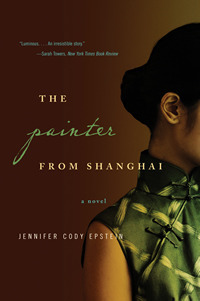

I discovered this myself while writing my first novel, The Painter from Shanghai (W.W. Norton 2008). As a former journalist–with both a BA and an MA in Asian Studies–I take both facts and history very seriously. At first even I was a little anxious about fictionalizing a real-life character from a different culture and era. But the story of prostitute-turned-post-Impressionist Pan Yuliang seemed ideal for a novel, since even in her native China there is very little documentary evidence about her life. In fact, when I began researching her in 1999, most people seemed to rely mainly on another fictionalized biography—one published anonymously during the ‘80’s. Even academics, I noticed, would refer me to this unattributed, novelized version for lack of better source material.

As my research progressed, though, I began to notice something else: namely, a reluctance by some of the sources I approached to be associated with a fictionalized history. No one said so in so many words. But there was a clear pattern of dropped email chains and unreturned calls from various professors and scholars of the “straight” history world to whom I’d reached. Having never encountered such reticence in my previous field of journalism, I found it somewhat baffling at first. But an early review for Painter shed some light.

Writing for the scholarly Asian Review of Books, editor Peter Gordon had many nice things to say about my novel. In the end, though, he admitted that the idea behind my novel unnerved him: “The problem is that the real Pan keeps on getting in way….one continually wonders how much is real and how much dramatized…. The result is that The Painter From Shanghai sits at the intersection of biography and fiction, a place which I personally find somewhat uncomfortable.”

Which led me to ponder: where, exactly, is that intersection? Or rather: what rules should be followed when mixing “real history” with writerly imagination?

For myself, at least, it’s actually pretty straightforward. There is no question that truth is important, and it is a period writer’s responsibility to get the details right wherever and whenever possible. But in the end, a novelist’s first job is to tell a good story. To craft a compelling yarn, peopled by characters her readers can not just picture but inhabit–live and breath, see and sigh and even smell through. And while reassuringly fact-checkable, names, dates and places alone simply don’t provide a broad enough palette to do that: to truly “flesh out” historical moments—e.g., drape them in human skin–sometimes one simply must fabricate.

Recognizing this, the rules I’ve set for myself are simple. I research my projects intensely, get all my facts straight, and resolve to do my best to stick to them. I am allowed, however, to take historical liberties that are at least somewhat plausible—in other words, don’t contradict broadly-accepted historical fact. For instance, in fictionalizing Pan Yuliang’s story I have her meet the Chinese revolutionary Zhou Enlai at Lyon University, and then again later on in Shanghai. There’s actually no historical proof the two ever really met. And yet the fact that these two real figures were in Lyon and Shanghai at the same time, and definitely knew people in common, made it seem credible to me that they might have met. Moreover, introducing Zhou as a character was a way to give readers a taste of the time’s political fervor and excitement, which was one of my goals as a novelist. And so, I picked him for my palette. The same rationale wouldn’t have worked for every character from the period, however. For instance, seating Mao Zedong at Pan’s table at Les Deux Magots would have been taking it too far, since anyone familiar with the story of China’s revolutionaries in Paris would know he wasn’t part of that cliché.

Similarly, in The Gods of Heavenly Punishment I’ve added a fictional bomber (Cam Richards) to the heroic band of Doolittle Raiders who flew our first strike against Japan. Confession: no one by that name ever existed. Still, almost everything that happened to Cam Richards did happen to a Doolittle Raider, with the exception of where his bomber crashes. In my novel, this happens in Japan-colonized Manchuria, which is not a stretch most readers would notice. Besides, I needed my heroine—who visits a Japanese settlement in Manchuria shortly after the crash—to receive an item that had belonged to Cam’s wife. So overall, I figured I was within my rights to move Cam’s doomed bomber further North than any of the Doolittlers actually flew. It would not have been within my rights, however, if I decided to add, say, a third nuclear bombing at the end of the Pacific War. For one thing, it would add nothing to the story I was trying to tell. But there’s also the fact that most people stop mid-page and think: “Wait, that didn’t happen.” Then they’d probably wonder why I wrote it, and whether other historical facts in my book were fabricated. At which point I’d be guilty of a far greater authorial sin than veering from history: losing my reader.

So to the extent that there are rules about mixing fact and fiction without bilious results, they probably boil down thusly:

1) Be factual whenever possible.

2) Don’t mess with the really big stuff.

3) Above all, tell a really good story.

That said, sometimes fictional narrative can play into historical truth in unexpected ways. One of my own more memorable research moments in Painter occurred over the Chinese lover I wrote into Pan’s early years in Paris. When my factchecker asked how I’d come across this character, I told the truth: that he was based on a painting of Pan’s, of a strong young man holding Chinese soil in his hands. I’d imagined him as a fellow artist, one of the Chinese students fermenting revolution in smoky Left Bank cafes. Also, someone younger than she was (I thought she’d like that).

“But where did you read about him?” asked my researcher, who happened to be Chinese. She went on to tell me that there’s a man who fits the same profile as my character who lived with Pan for years in Paris, and now lies buried next to her in Montemarte.

For a moment I just stared at her. Then I burst out laughing. Well, what do you know, I thought. In this one case, at least, my fiction had led me straight to the facts.

*Note: This post originally appeared in the excellent historical fiction blog Historical Boys.

April 17, 2013

On War, Image and Photography…a Literate Lens Look at “Gods”

“If everyone could be there just once, to see for themselves what white phosphorous does to the face of a child, or what unspeakable pain is caused by the impact of a single bullet or how a jagged piece of shrapnel can rip someone’s leg off – if everyone could be there to see the fear and the grief, just one time, then they’d understand that nothing is worth letting things get to the point where that happens to even one person, let alone thousands.”

—James Nachtwey, photographer

***

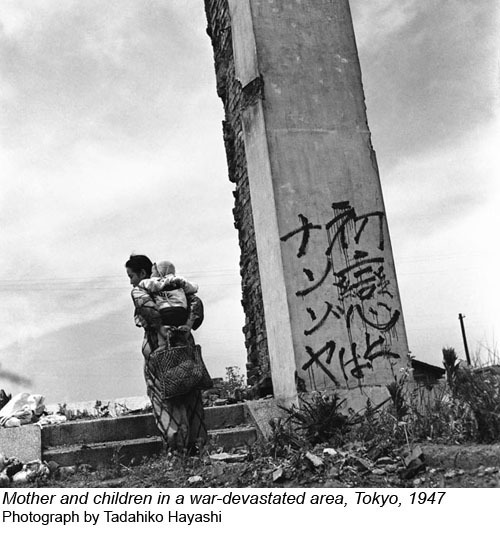

Last week, I was thrilled to be the subject of a thought-provoking interview on the photography/literature blog The Literate Lens, which is written and curated by my friend Sarah Coleman. She covered some very interesting new angles in her take on The Gods of Heavenly Punishment, and in particular was curious about my use of so many photographs by the Japanese photographer Hayashi Tadahiko. Here’s our exchange on the subject:

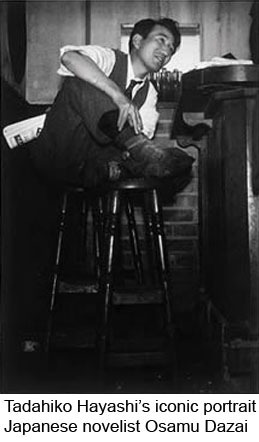

LL: Can you tell us something about Hayashi Tadahiko, the Japanese photographer who took several of the photographs you feature in the book?

JCE: I discovered him through that photograph I mentioned before—“Dancer on a Rooftop”—but realized upon researching a little that he’d taken a few other photos I’d admired in the past, including an iconic one of the Japanese novelist Osamu Dazai about to topple off a bar stool in the Ginza. He was born in 1918 into a family of photographers—interestingly, his mother was the real talent in the family—so he learned the basics of the trade growing up, and was skilled as a portrait artist. He went to photography school in Tokyo, where he was apparently such a big partier (maybe how he got that great shot of Dazai?) that his family finally cut him off financially. He spent the latter part of the Pacific War in Beijing and then returned to Tokyo, where he took pictures of orphans (like “Shoeshine Boy,” which I also use in the novel) and the high life alike.

JCE: I discovered him through that photograph I mentioned before—“Dancer on a Rooftop”—but realized upon researching a little that he’d taken a few other photos I’d admired in the past, including an iconic one of the Japanese novelist Osamu Dazai about to topple off a bar stool in the Ginza. He was born in 1918 into a family of photographers—interestingly, his mother was the real talent in the family—so he learned the basics of the trade growing up, and was skilled as a portrait artist. He went to photography school in Tokyo, where he was apparently such a big partier (maybe how he got that great shot of Dazai?) that his family finally cut him off financially. He spent the latter part of the Pacific War in Beijing and then returned to Tokyo, where he took pictures of orphans (like “Shoeshine Boy,” which I also use in the novel) and the high life alike.

One thing that was particularly interesting about his style to me was that he wasn’t afraid to stage things: he clearly wanted his images to tell stories, and he would use props and other devices to tell them.

In another picture of his—of the woman walking in rubble, next to a pillar with “What was the point” scrawled on it (at left)—it is said that he actually painted the graffiti himself. His interest in narrative is also evidenced by the subject of his first book of photographs, titled Shosetsu no Furusato, for which he travelled around Japan photographing settings that have been described in various Japanese novels.

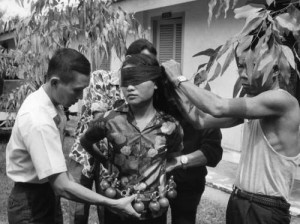

Sarah also had a followup question about how I see the differences between conveying war in words and images–which has been bouncing around in my thoughts over the last week. Frankly, it’s a hard one to answer–and the truth is, I think photos (like the extraordinary one with which Sarah starts off her piece) probably do a better job at exposing the brutality and shock inherent in war–which is likely why war photography and peace activism are so deeply intertwined.

To be honest, I don’t think anything I could write in description of the man in the top picture would do justice to his actual appearance, and the instant, visceral story that goes with that appearance. But I do think words can give depth and complexity to war in a way that pictures alone can’t. For instance, according to the caption the man was attacked and disfigured because he didn’t support the 1994 genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda. Those words for me summon up a whole series of questions that can’t be answered by image alone: when did he protest the genocide? How? To whom? What had he seen that made him protest? What happened to his attackers? Where is he today? In other words, I think image and word each bring something different to the narrative table. Which is why for me they are such a powerful combination–in fiction as well as in journalism.

The exchange made me surf a bit for other war photographs that both tell stories and raise narrative questions. Here are a few I found:

You can find Sarah’s full interview with me in The Literate Lens here.

April 11, 2013

On Drones, the Fog of War and Obama vs. LeMay

“How much evil must we do in order to do good?”

It’s a question posed by Robert MacNamara in Errol Morris’s 2003 documentary The Fog of War, and one I’ve thought a lot about in these past weeks as the debate over our drone policy has escalated–most recently, with Tuesday’s release of top-secret intelligence which outlines just how casual our overseas killing policy has become.

The summary of intelligence reports from McCLatchy Newspapers debunks many of Obama’s assertions in the past, including the idea that drone attacks minimize (or even negate) civilian casualties. Also, that they target only “specific senior operational leaders of al Qaeda” who are plotting “imminent” attacks on Americans. As it turns out, al-Qaeda members are a mere minority of total drone casualties—and senior al-Qaeda leaders are killed only rarely. In fact, sometimes our drone operators aren’t really sure who they are killing.

In some ways, the McClatchy report seems to posit a whole new world, policy-wise–particularly since it follows a New York Times story that our Pakistan drone program was launched only after the C.I.A. agreed to assassination of a Pashtun tribal leader the Pakistan government wanted dead. And yet as someone who has spent much time immersed in Pacific War lore over the past couple of years, there’s a lot about this conflict that feels eerily familiar. Sure, the technology has changed, and along with it the vocabulary: surgical and signature strikes, pinpointed targets, remote pilots. The truth, however, is that we have taken comparable technological leaps in the past, and skirted the same ethical questions about civilian deaths.

On March 9th 1945, 334 bombers—each representing an investment of a half-million dollars, each a pinnacle of the time’s airpower technology—took off at dusk from the recently-captured Marianas, on a mission dubbed “Operation Meetinghouse.” By midnight the planes were swarming over sleeping Tokyo. Air raid sirens wouldn’t sound until well after the attack began, but most Japanese gave the droning engines little thought. In past months American flyovers had been both common and harmless enough that they were referred to almost affectionately, as “our regulars.”

Meetinghouse, however, proved devastatingly irregular. Not only was Tokyo constructed largely out of wood and paper, but LeMay had ordered the planes in at unprecedentedly low altitudes—between 4,500 and 8,000 feet—to accomplish what he called precision bombing. Between that, the 1165 tons of petroleum-packed explosives the planes carried (another first: napalm) and a brisk Northwesterly wind, the attack created one of the fiercest infernos ever seen in a city. “People were burning alive right in front of me,” Yoshiko Hashimoto, a survivor, told me. “Women’s hair was on fire. Men’s clothing was on fire. There were so many people rolling around on the ground.” The American pilots would recall smelling acrid smoke and burning flesh from their cockpits. Returning to base, they’d scrape soot from their plane’s bellies.

Like our ongoing overseas drone strikes, Operation Meetinghouse was orchestrated and carried out by a small handful of military brass, without congressional or even presidential oversight. Its masterminds included Major General Curtis LeMay as well as MacNamara, at the time a captain in the Office of Statistical Control. It’s ostensible goal: to decimate Tokyo’s industrial military complex. The latter was said to be inextricably intermeshed with civilian life, since some residential areas also housed “shadow factories” that produced prefabricated materials for Japan’s aircraft factories.

At least a hundred thousand Japanese died between midnight and dawn that night—over three times Dresden’s death toll, and significantly more than the initial tolls in either Hiroshima or Nagasaki. Sixteen square miles of city were incinerated. In the days afterwards LeMay was hailed as an airpower superstar. “I want you and your people to understand fully my admiration for your fine work,” General Hap Arnold wrote him. “Your recent incendiary missions were brilliantly planned and executed.” If he or anyone else had serious qualms about the fiery deaths of tens of thousands of civilians, they were left unsaid–though a follow up XXI’st Bomber Command report seemed slightly defensive on the topic. “The object of these attacks was not to indiscriminately bomb civilian populations,” it noted. “The object was to destroy the industrial and strategic targets concentrated in the urban areas.”

In truth—and as both LeMay and Arnold were quite likely aware—Japan’s military-industrial complex had already been badly damaged by a year-long U.S. Naval blockade. In short, they were lying about who and why they were so “precisely” striking—or at very least, misrepresenting the truth. Yet both the press and the public bought their argument; there was little media coverage and even less debate. In fact even today the Tokyo firebombing remains deeply in the shadow of the atomic bombings that followed five months later. And yet the questions it raises remain strikingly relevant seventy years later, as we consider when, how and who our drones should kill.

Take, for example, the idea that civilian casualties are a legal, acceptable, and even inevitable consequence of a “just” war—something implicit in the arguments of both George Bush’s and Barak Obama’s administrations. Initially LeMay rationalized the Tokyo attack in the same way. “The entire population got into the act and worked to make those airplanes or munitions of war,” he claimed. “We knew we were going to kill a lot of women and kids when we burned that town. Had to be done.” I thought of this comment when reading Dexter Filkin’s New Yorker article earlier this year, in which he recalled talking to American officials about the 2009 drone strike in Al Majalah, Yemen. The attack killed fourteen Al Qaeda militants and forty-one civilians, and the officials “felt bad about it,” Filkins wrote. “But the aerial surveillance, they said, had clearly showed that a training camp for militants was operating there.” In other words, militancy in Yemen was so enmeshed with civilian life that it was impossible to hit one without hitting the other. Had to be done.

And yet the architects of Al Majalah–like those of our Pakistan program–may look back on their handiwork with less certainty then they now profess. After all, both LeMay and MacNamara did: “LeMay said if we lost the war that we would have all been prosecuted as war criminals,” MacNamara reminisces in The Fog of War. “And I think he’s right. He … and I’d say I … were behaving as war criminals.”

Something else to consider: for all of the napalm and flame we unleashed on Japan’s cities—burning hundreds of thousands of civilians to death in the process–there remains little evidence that those operations (as opposed to the surreal devastation wrought by Fat Man and Little Boy) brought our enemy closer to capitulation. Indeed, it’s possible they did the opposite—just as Japan’s bombings in China and Germany’s blitzes on London arguably strengthened the will of those besieged populations to fight on. And just as, by many accounts, our drone strikes in Pakistan and elsewhere are fueling recruitment by militant groups—and are almost certainly fueling anti-Americanism.

To be sure, there are some big differences between the Pacific War and our War on Terror. For one thing, there’s little question that drone strikes cause fewer casualties than city-wide firebombings. And while CIA Director John Brennan’s 2011 claim that “there hasn’t been a single collateral death” by drone has proven to be offensively inaccurate, the general estimates for drone-related civilian casualties generally range between the mid- to the high-hundreds (a figure chillingly humanized in this recent online infographic, “Out of Sight, Out of Mind”). Moreover, drone attacks put virtually no American lives at risk — unless, of course, you count the Americans at whom we target them.

But whether we are talking hundreds of civilian deaths or hundreds of thousands, the central narrative remains the same. Once more, we are summarily executing people whom we think might be our enemies. We are calling that “justice,” and then rationalizing untold numbers of civilian deaths in the name of that “justice.” And once more, a small group of highly-placed men–led by Barak Obama himself–are doing both the deciding and the killing. And then misleading us about it.

Which leads me to think that once the fog of this war has lifted, we’ll confront another quandary MacNamara poses in Morris’s documentary: How much evil must we do in order to do good?

If the lessons of the LeMay’s firebombings are any indication, the answer will likely be: far too much.

April 10, 2013

The Historical Novel Society

“[A] memorable time is magnificently portrayed by this knowledgeable, talented author. [The Gods of Heavenly Punishment] is a superb read, without being saccharine or hyped, and necessary historical fiction.”

April 9, 2013

Reading Group Guide: The Painter from Shanghai

Have a book group? I’d love to meet it!

To schedule a chat or visit, contact me.

In rendering Yuliang’s years working as a prostitute, Epstein depicts the intersection of the sexual economy, the business elite, and political leadership. How do the intrigues of the brothel affect the economy and government in Wuhu?

How does poetry play a role in Yuliang and Zanhua’s relationship? How does their shared appreciation for poetry stand in contrast to their feelings about visual art?

Yuliang’s budding talent for sketching is not revealed until chapter sixteen. Do earlier chapters contain any hints of her artistic abilities?

How is Shanghai different than Wuhu? How does Yuliang’s life change after she moves to Shanghai?

What results from Yuliang’s confrontation with the women in the bathhouse in chapter twenty-four? What does this scene reveal about Chinese female society— and what does it reveal about Yuliang?

Teacher Hong instructs Yuliang to “see the skin as more than simply skin.” Jingling, as she mentors Yuliang in the brothel, advises her protégée to remember that “it’s just skin.” Whose advice does Yuliang follow, and why? Why is painting nude figures important for Yuliang?

How does politics play a role in the story? To what extent is Yuliang a political person?

Both Xudun and Zanhua have strong feelings about politics and government in China. What two ideologies do these men represent? Are they entirely opposed?

In the 1920s and ‘30s Shanghai was often called “the Paris of the East.” As depicted in the novel, how does Shanghai compare with the French capital? Both cities are cosmopolitan, but in different ways. How do you see those differences?

Why does Yuliang demand an abortion? Do you think she comes to regret that decision?

How does the course of Yuliang’s personal and artistic career compare with that of her mentor, Xu Beihong?

In chapter thirty-three, when Xudun takes Yuliang to the top of Notre Dame Cathedral—in what seems to be one of the most exciting and romantic moments of Yuliang’s life—her thoughts return to her uncle, who sold her into prostitution. Yuliang, however, frequently professes a desire to stay “rooted in the present.” To what extent is she able to do that? How do the wounds of her past manifest themselves later in Yuliang’s life? How do they affect her art?

After she moves to Nanjing—after years in Paris and Rome and a stint as an outspoken teacher at the Shanghai Art Academy—why does Yuliang submit to acting as “the second woman” to Guanyin in Zanhua’s household? Why does Yuliang feel sympathy for Zanhua’s first wife? Do you think Guanyin deserves sympathy?

“It is hard to find heroes in times such as these,” says Qihua, referring to Zanhua. After all that is revealed about him later in the book, does Zanhua emerge as a hero in this story? Does Xudun? Had Xudun lived, do you think Yuliang would have chosen him over her husband? Would you want her to?

In moving back to Paris, Yuliang chooses a life of free artistic expression over a more traditional life of marriage. The last chronological scene in the novel is the prologue. Based on that opening scene, how do you think Yuliang views her life’s choices? How do you view them? Having finished the book, how has your feeling about her life and character changed? Why do you think Epstein chose to begin the novel with this scene?

At the end of her life, Pan Yuliang had become known in her Paris circle as the “Woman of Three ‘No’s” for her steadfast refusal to work with dealers, take French citizenship, or enter into love affairs. Why do you think she was so firmly against each of these things? Are they in keeping with the image of her you’ve formed from reading The Painter of Shanghai?

April 8, 2013

Reading Group Guide: The Gods of Heavenly Punishment

Have a book group? I’d love to meet it!

To schedule a chat or visit, contact me.

Kenji Kobayashi and Anton Reynolds both commit horrific crimes against humanity during the war, but neither character comes off as purely villainous. Discuss the moral ambiguity at the heart of the novel. How do you judge these characters?

When Yoshi is surprised and terrified by the firebombs that rain down on her city, the reader has seen the attack being planned. What is the effect of our knowing more than Yoshi does, in this instance?

There is a terrible irony to the fact that Anton is able to help plan the firebombing of Tokyo only because he knows the city so intimately. Later, there is a tragic irony to the fact that Lacy’s “come-back-to- me-safely ring” does indeed come back safely. Where else is irony at work in the novel?

Yoshi, Cam, and Billy all have troubled relationships with their parents. Describe these relationships. How do they differ and what do they have in common?

Both Yoshi and Billy pass from innocence to maturity over the course of the novel. Describe how both characters change and what forces them to change.

Discuss Billy and Yoshi’s meeting in the brothel, from Billy’s perspective. What is it about his encounter with Yoshi, and about returning to a changed, war-torn Japan after so many years, that helps shy, nervous Billy act so bravely?

How does the war bring people together, in addition to tearing them apart? Discuss some of the relationships formed in the novel during wartime.

Yoshi’s life as she knew it has ended. Do you think she finds redemption? If so, how?

Yoshi tells Lacy that she lost her husband in the war. Describe Yoshi’s relationship with her husband, Masa. What has the war done to him? What does it mean to lose someone in the sense that Yoshi means it?

Yoshi’s hawk; Billy’s camera; Hana’s book of D. H. Lawrence poems; Lacy’s ring: many of the characters in the novel carry talismans, objects from their past that seem almost to be imbued with magical powers. What is the significance of these objects in the novel? Do you have any objects like this in your life? In your family’s history?

Look back at the opening scene of the novel, with Cam and Lacy on the Ferris wheel. Do you experience the beauty and innocence of that scene differently once you’re aware of the events to come? Was your family affected by World War Two? Do you know anyone who had an experience like Yoshi’s, Billy’s, Lacy’s, or Cam’s?

On the “Gender” of Historical Fiction, Manly Book Covers and Such

Earlier this week I was delighted to guest post for the very excellent historical fiction blog Reading The Past. I’ve gotten a lot of questions about how the covers for my novels are come up with and how my book is marketed to specific groups, so when ReadingthePast’s host Sarah Johnson mentioned she too had an interest in the topic I thought I’d spend some time on the subject. What, exactly, gives certain genres–including historical fiction–”genders,” and how those choices end up becoming part of the marketing process of books? Here were some of my musings:

***

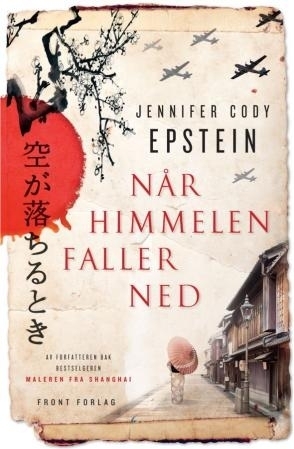

“As a writer, would you say you push the boundaries of women’s literature?”

We were sitting in a hotel lounge in the lovely but rainy city of Bergen, where a journalist was interviewing me about my new book. The Gods of Heavenly Punishment (or When the Sky Fell, as my Norwegian publisher titled it—Norwegians, it seems, distrust religious references in titles) is a war novel, set against the blazing backdrop of the 1945 Tokyo firebombing. The story is told through the perspectives of five central characters: two female, three male.

“I don’t really see my work as exclusively ‘women’s’ literature,” I said, setting down my teacup. “Particularly this novel. I mean, I welcome women readers, obviously. But I wrote it to be read by both genders.”

My interviewer chewed her pen for a moment. “Well,” she said. “If you did write women’s literature, would you say you were pushing its boundaries?”

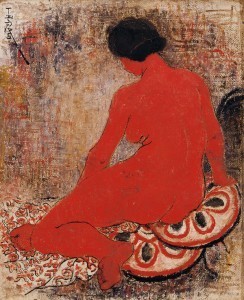

I suppressed a smile. This wasn’t the first time I’d faced this label, “women’s literature.” But I still found it somewhat puzzling. Granted, my first novel, The Painter from Shanghai, was about a woman: Chinese prostitute-turned-post-Impressionist Pan Yuliang. Written third-person, present-tense and encompassing Asian history, art, travel and romance, it’s a story that arguably appeals largely to my gender. And while I hadn’t written it exclusively for fellow females, I also hadn’t argued with my publisher when they opted to market it that way, giving it a gorgeous but distinctly feminine cover (a woman’s profile, sepia-toned and deeply saturated with color) and presenting it as an ideal book-group pick. The truth is, I loved the cover. And their strategy was a very wise one, since the book indeed did well with book groups and sold decently in the States. It also sold in sixteen other countries under equally feminine-looking covers. Including Norway, where it became a bestseller.

So I’m not really complaining. Or at least, I know I shouldn’t be. After all, while men make up the bulk of fiction writers in the world, women are indisputably its biggest readers—something Ian McEwan noted a few years back after going to a park to give away thirty novels. As he reported in the Guardian, a full twenty-nine of those books were accepted by women—while all men but one (an unusually sensitive soul, it seems) declined. “When women stop reading, the novel will be dead,” he concluded. So if I had to choose one group to appeal to, it’d clearly be the ladies.

And yet it still sits a little strangely on me; this idea that I somehow read as more “womanly” than do my male counterparts–or even female ones who don’t get marketed the same way (think Jennifer Egan, Nicole Krauss, Gillian Flynn). After all, my literary influences are split pretty evenly between pink and blue. I love Toni Morrison, but no more than I love Nabakov. I’ve read as much Sarah Waters as I have Phillip Roth. Or for that matter, Ian McEwan. In other words, I don’t really see myself as an overtly “womanly” reader.

I also realize, however, that being labeled a “woman’s writer” often goes hand-in-hand with another label about which I have less complex feelings: “historical fiction.” There is no doubt whatsoever that my last two novels are of that genre (I should know, since I spent years researching each of them). Strangely, though, when I first set out to write a historical novel I didn’t anticipate it pushing me towards one gender more than another. After all, history itself isn’t considered more female than male. If anything it’s the other way around (sic: history). And yet, do an Amazon search for “historical fiction” covers and the vast majority have women’s faces or bodies or accessories (jewelry, gloves, perfume bottles) on them. This is probably due to the fact that for a very long time, novels labeled “historical fiction” were often far heavier on fiction than on factual history. Many, in fact, were interchangeable with “romance” (e.g., bodice-ripper)—something my late grandmother’s bookshelves quite fully attested to.

I hasten to add that I have nothing against those sorts of novels. Indeed, growing up I loved nothing more than sneaking Grandmother’s monthly-delivered Harlequins into my bag, then reading them later with quivering excitement, in secret. But writing The Painter from Shanghai that wasn’t the genre that I had in mind. Sure, there’s sex in it—pretty good sex, from what I’m told. But what I really wanted to get at was the history—the amazing, rich, tumultuous history of Chinese politics and art, from the turn of the century through the Chinese Communist revolution. And again, I didn’t think that would appeal just to women. It’s also why I was slightly surprised when I saw the American cover for my new novel, The Gods of Heavenly Punishment. Emblazoned with Japanese-style flowers and a girl with a parasol, it was just as gorgeous as the cover of The Painter From Shanghai. And aesthetically, I loved it just as much. But I did ponder, briefly, about whether it was fully representative of my new novel, which is about both men and women, and about war.

In the end, though, I again went with the prevailing wisdom about how my novels should be marketed to our predominantly-female readership. And in the end, I’m very glad that I did. The book is so beautiful I teared up when I first held it—which is one of the best feelings any novelist can hope for. What’s more, everyone who sees the cover raves about it–men included. I’m also sure it leads many a perusing, potential reader to pick it up in bookstores, which, when it comes down to it, is what a great cover is really for. I will admit, though, that I laughed when I saw the Bergen newspaper piece, which came out a day after my interview. The title: “Women Writers Push the Boundaries of Women’s Literature.”

And there, front and center, was my novel….

….looking absolutely beautiful. As always.