Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 216

April 11, 2017

Terror in Stockholm

Last Friday, an ISIS supporter rammed a truck into a department store in the heart of Stockholm, Sweden, killing four people and injuring 15. That same evening, news broke that Swedish police had arrested a 39-year old man from Uzbekistan for complicity in the attack. By Sunday morning, Swedish media reported that the man’s social media account indicated his support for both the Islamic State and the Islamic Party of Liberation, Hizb-ut-Tahrir.

Fifteen years ago, Swedish migration authorities faced a problem. They had seen a marked uptick in asylum seekers from Uzbekistan who claimed to be persecuted for their religious beliefs. That was not in itself surprising: Especially after an attempt on President Islam Karimov’s life in 1999, the government in Tashkent was well known for repressing Islamic groups that diverged from the country’s traditional, tolerant version of Islam.

Remarkably, many of these migrants claimed membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir (HT). Created in 1953 by the Palestinian cleric Taqiuddin al-Nabhani, HT is a radical Salafi outfit whose main ambition is to create a global Caliphate. In other words, it has the same end goal as ISIS and al-Qaeda, but claims to be working toward that goal peacefully. Its ideology, of course, is virulently anti-Western and anti-Semitic, and even HT acknowledges that at the end stage of their struggle violence may be necessary against those who “stand in the way” of the Caliphate. In Denmark, an HT leader was convicted of inciting hatred after his group published and distributed leaflets urging the murder of Jews.

Why would someone actually claim to belong to an extremist group such as HT when requesting asylum? Well, Swedish authorities had determined that the Uzbek government’s targeting of HT was particularly harsh. For human rights reasons, it was out of the question to send peaceful Muslims back to Uzbekistan. In other words, Swedish authorities had enacted directives that practically guaranteed a follower of an extremist Islamist group asylum in the country. HT, of course, knew this and urged its members to keep coming.

Some among the Swedish authorities were well aware of the likely but unintended consequence of this policy: the formation of radical Islamist cells in the country. The only way to change the policy would be to prove that the group was linked to violence or terrorism. Germany banned HT in 2003 on the grounds that its hateful ideology aims to overthrow the constitutional order. But in Sweden, unless HT could be classified as a violent extremist group, Sweden would keep welcoming them.

In later years, it appears that the Swedish Security Police were working to stem the flow of HT members seeking refuge in the country. There are a number of cases where the Security Police have intervened to deny HT sympathizers residence permits. However, regulations still prevent deporting many of these individuals to countries where they risk torture or the death penalty. While information is still sketchy, the Uzbek national in this case was apparently denied a residence permit and went off the grid rather than face deportation. No measures to de-radicalize these followers appear to have been initiated.

Importantly, the fact that the Uzbek national arrested was apparently a supporter both of HT and the Islamic State makes this attack a textbook case of the consequences of failing to define the enemy. When anti-Western and anti-Semitic hatemongers use violence, Western nations deploy thousands of troops and predator drones to kill them abroad. But if the same hatemongers claim to be part of a group that does not find the use of force to be the right tactic at the present time, we seek dialogue with them or provide them refuge. Clearly, in these radical environments, the line between various groups and organizations is permeable at best. Individuals can be part of multiple networks—some violent only in theory, others very much in practice.

Worse, in most Western countries the Islamist ideologues of the Muslim Brotherhood are accepted as representatives of a Muslim community that, for the most part, has never supported them, let alone elected them. But because Western states shower their associations with taxpayer money, they acquire the means to exert influence over Muslims and thus impede their integration.

From “war on terror” to “countering violent extremism,” Western nations have spent close to two decades making war on either a tactic or a nebulous concept. They have refused to accept that the real issue, just like fascism and communism before it, is the ideology that nurtures hatred of who we are and what we stand for.

By not defining the enemy, we also abandon the brave Muslims who do fight the radical ideology in their midst and work to preserve secular space in the Muslim world. To these Muslims, our attitude is bewildering. To them, it is obvious that one can and must fight the radical Islamist ideology while making clear that this ideology does not represent the broader Muslim community. It should be obvious to us too.

Californians Are About to Start Noticing the Pension Crisis

For years, California’s pension crisis has been swept under the rug by powerful public unions and pliant politicians who over-promised and underfunded pensions for government workers. But the jig is almost up, and taxpayers are going to notice. Bloomberg reports:

California cities and counties will see their required contributions to the largest U.S. pension fund almost double in five years, according to an analysis by the California Policy Center.

In the fiscal year beginning in July, local payments to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System will total $5.3 billion and rise to $9.8 billion in fiscal 2023, according to the right-leaning group that examines public pensions.

The increase reflects Calpers’ decision in December to roll back the expected rate of return on its investments.

Calpers has concealed the depth of the pension shortfall by using unrealistic rates of return in its accounting estimates. But to stay solvent, it was recently forced to cut its projected rate from 7.5 percent to 7.375 percent (with more reductions almost certainly on their way). The state will need to make up the difference with tax increases and austerity.

Democrats may be able to force through new taxes (California’s are already among the highest in the country) to plug a part of the funding hole. But education and social services are sure to take a significant hit as well, especially in counties removed from the booming coastline—meaning that California’s most vulnerable residents will pay much of the price for the state leadership’s long-running mismanagement of public funds.

From Responsibility to Protect to Slave Markets

If a Republican President had invaded Libya and overthrown its government, then left bloody chaos, terrorism and rampant arms smuggling behind, our courageous press corps would be all over the story like a chicken on a June bug.

But fortunately all this happened under President Obama, so we don’t hear all that much about it. And when we do, nobody tries to assign blame to the arrogant ignoramuses who “organized” this disaster.

But the latest news, that slave markets are now operating in Libya, where desperate black Africans are being bought and sold as slaves, ought to trigger some kind of response. The Guardian:

The north African nation is a major exit point for refugees from Africa trying to take boats to Europe. But since the overthrow of autocratic leader Muammar Gaddafi, the vast, sparsely populated country has slid into violent chaos and migrants with little cash and usually no papers are particularly vulnerable.

One 34-year-old survivor from Senegal said he was taken to a dusty lot in the south Libyan city of Sabha after crossing the desert from Niger in a bus organised by people smugglers. The group had paid to be taken to the coast, where they planned to risk a boat trip to Europe, but their driver suddenly said middlemen had not passed on his fees and put his passengers up for sale.

“The men on the pick-up were brought to a square, or parking lot, where a kind of slave trade was happening. There were locals – he described them as Arabs – buying sub-Saharan migrants,” said Livia Manante, an IOM officer based in Niger who helps people wanting to return home.

She interviewed the survivor after he escaped from Libya earlier this month and said accounts of slave markets were confirmed by other migrants she spoke to in Niger and some who had been interviewed by colleagues in Europe.

Again, if Republicans were responsible for this it would be the Biggest. Disaster. Ever.

As it is: crickets.

Notes on Cost Disease

A paradox: even though improving technology and globalization ought to be massively cutting costs, Americans over the past fifty years have witnessed sharply rising costs for certain fundamental goods and services. And in many cases, those sharply rising inputs have not been matched by proportional benefits in outcomes, the result being a hard-to-measure but indisputable productivity fall in those sectors.

One popular explanation is “the Baumol effect,” a shift toward higher salaries in certain fields that has fascinated economists since its discovery. But the Baumol effect predicts that workers should enjoy increasing incomes in affected areas, something that is not happening. Something else must be going on.

First we will present the data on primary, secondary, and college education, health care, housing, and infrastructure. These do not exhaust the possibilities; the costs of acquiring major weapons systems for the military is just one of several others we will leave aside for the time being.1

Then we will look at the Baumol effect and other possible supplementary explanations for the data. Some of these are widely discussed in the literature, others not much, if at all. Unfortunately, these do not sum to a reasonable explanation for cost disease. They are best thought of as fragments of a possible explanation that remain to be investigated and integrated. No one yet really understands this problem.

Finally, and briefly, we will address some of the political implications of cost disease.

Primary/Secondary Education

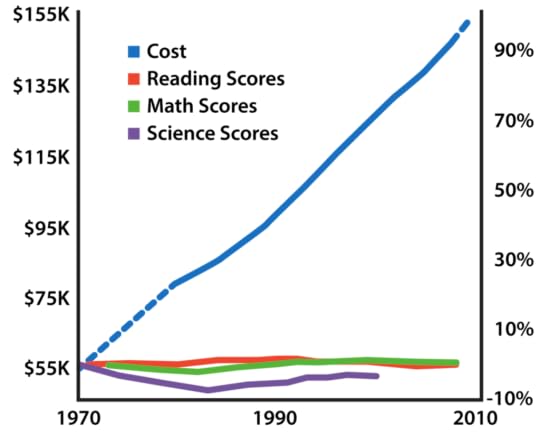

The consensus concerning the costs and outcomes of primary education states that per-student spending has increased about 2.5 times in the past forty years, even after adjusting for inflation.2 At the same time, test scores have stayed relatively stagnant.3 For example, high school students’ reading scores went from 285 in 1971 to 287 today, a difference of 0.7 percent.

1. Inflation-Adjusted Total Cost of K-12 Public Education and Percent Change in Achievement for 17 Year Olds, Since 1970

Source: Cato Institute

The data show some heterogeneity across races: White students’ test scores increased 1.4 percent and minority students’ scores by about 20 percent. But school spending per capita does not explain much or most of the minority students’ improvement, which occurred almost entirely during the period from 1975 to 1985. School spending has been on the same trajectory before and since that decade in both white and minority areas, suggesting that there was something specific about that decade that improved minority scores so much. Most likely, it had to do with the general improvement in minorities’ conditions and, with them, changing expectations about education and possibilities for upward mobility. As far as cost disease is concerned, the key point is that most of the increase in school spending per capita took place after 1985, and demonstrably helped neither whites nor minorities.

My analysis shows that the cost of primary/secondary education really did more or less double in these forty years without any concomitant increase in measurable quality.4 It has little to do with adding costly special ed services, nothing to do with how we measure test scores, nor is it simply a “ceiling effect.”

In that light, imagine a choice set before a poor person—white, black, or any other demographic. Would you prefer to send your child to a 2016 school, or to send them to a 1975 school and get a check for $5,000 every year? That really is the stake here: 2016 schools have minimal test-score advantages over 1975 schools, but cost $5,000 more per year, inflation adjusted. That $5,000 comes out of the pocket of somebody—either taxpayers, or other people who could be helped by government programs.

College/University Education

The data for college/university education is even worse. The inflation-adjusted cost of a university education was something like $2,000 per year in 1980.5 Now it’s closer to $20,000 per year. No, it’s not because of decreased government funding, and the trajectories are similar for public and private schools.6

2. Percentage Increases in Consumer Prices Since the First Quarter of 1978

Source: Bloomberg (via Valuewalk)

There is no equivalent of “test scores” to measure how well colleges perform, despite some recent efforts to create reliable metrics. But who thinks that colleges today provide $18,000/year greater value than colleges did forty years ago? Who would rather graduate from a contemporary four-year college as opposed to graduating from one in about 1967 and getting a check for $72,000 (or, more realistically for many, having $72,000 less in student loans to pay off)?

As far as I can see, my parents’ college experience seems to have had all the relevant features: classes, professors, clubs, roommates, and standard-issue angst. I might have gotten something extra for my $72,000, but it’s hard to figure out what it was.

Health Care

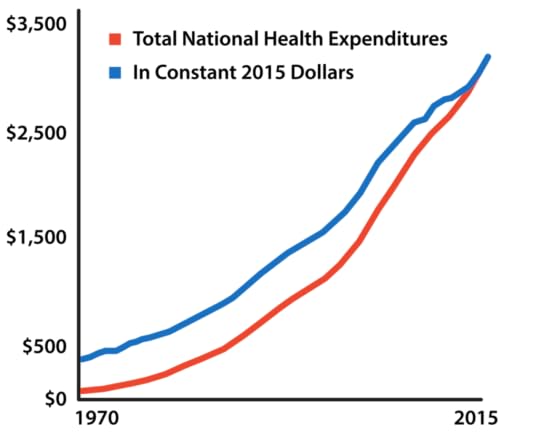

Cost disease has certainly not spared health care. Take a look at Figure 3. The cost of health care in the United States has about quintupled since 1970. Most likely it has actually been rising since earlier than that, but data to show it is scarce or of questionable reliability. Still, if we set the base year at 1960 instead of 1970, the increase comes to about 800 percent in fifty years.

3. Increase in Total U.S. Health Expenditures in Billions, 1970-2015

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

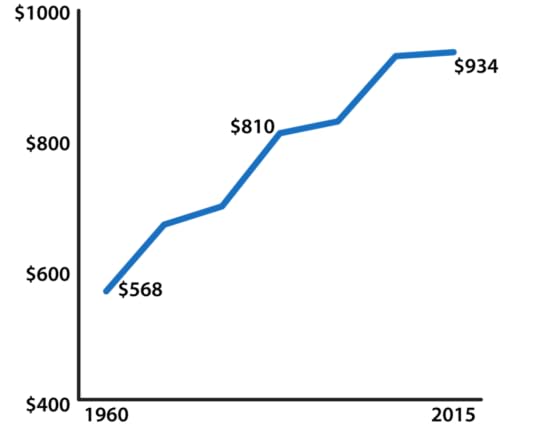

This has had the expected effects. Average workers in 1960 spent ten days’ worth of their yearly paychecks on health insurance; average modern workers spend sixty days’ worth—about a sixth of their entire earnings.7 As a result, both before and after the Affordable Care Act, a fair number of poorer Americans put off buying insurance or seeking medical (and dental) care.

4. Percentage of Americans Putting Off Medical Treatment Because of Cost

Source: Gallup

This is not necessarily for nothing. Life expectancy has gone way up since 1960, for example.

But life expectancy depends on many other factors aside from per capita health care spending. Better sanitation, nutrition, and a reduction in tobacco use, plus advances in technology that don’t involve spending more money have clearly mattered. For example, ACE inhibitors, invented in 1975, have probably increased life expectancy a great deal, but they cost only $20 for a year’s supply and replaced older drugs that cost about the same.

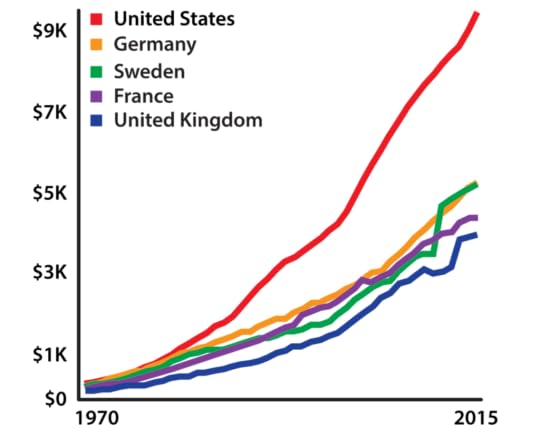

If we want to calculate how much lifespan gain more health care spending has produced, we find ourselves faced with a series of regression analysis challenges. But we have some options short of such an ordeal. One has to do with international comparisons.

5. Health Expenditures Per Capita vs. Life Expectancy

Sources: OECD, World Bank, via Our World in Data

6. Increases in Health Expenditures, 1970-2015

Source: OECD

The data show that, for example, South Korea and Israel have about the same life expectancy as the United States but pay about 25 percent of what we pay. So we might conclude that it is very possible to get the same improving life expectancies as Americans have experienced without octupling health care spending.8

Again, spending per capita cannot possibly be the only criterion in cross-national comparisons. But it is notoriously difficult to calculate this. The Dutch have tried, and the example is instructive.

The Netherlands hiked its health budget by a lot starting around 2000, sparking several studies on whether, and how much, that increased life expectancy. A good meta-analysis lists six studies that tried to find the answer, and here is the range of their estimates: 0.3 percent, 1.8 percent, 8.0 percent, 17.2 percent, 22.1 percent, 27.5 percent. The meta-analysis also mentions two studies not included, one finding 0 percent effect and one finding 50 percent effect, presumably to narrow the statistical mean.

How to interpret this very wide range? The best conclusion anyone could arrive at was that, yes, it is likely that increased health care spending contributed to the recent increase in life expectancy in the Netherlands—but the methodological problems involved were so daunting that no one can reliably say by how much.

Even if the Dutch effort had produced more useful results, it would still be irresponsible to apply it to health spending in the United States over the past fifty years: The marginal social differences between the two nations are large, and anyway the 1950s are not the 2010s. If we irresponsibly take their median estimate and apply it to the current question anyway, we get that increasing health spending in the United States by 800 percent per capita over half a century has bought about one extra year of life expectancy.

Other (less irresponsible) studies come up with a slightly different number. One attempt to directly estimate a health spending (as percent of GDP) to life expectancy conversion, and says that an increase of 1 percent in GDP corresponds to an increase of 0.05 years in life expectancy. That works out to only 0.65 years of added life expectancy gained by health care spending since 1960.

If these numbers seem very low, remember all of those controlled experiments where giving people insurance doesn’t seem to make them much healthier in any meaningful way.9 That may be because having insurance has little bearing on lifestyle choices, and over time mortality rates for diseases tied to specific pathogens (bacterial, viral, fungal) has decreased less than mortality rates for lifestyle-driven diseases (diabetes, heart disease) have risen.

That said, we can ask the standard-form question we have used before: Would an average poor or middle-class person rather get modern health care, or get the same amount of health care as their parents’ generation did but with modern technology like ACE inhibitors—and also earn $8,000 extra a year?

Housing

Most of the important commentary on the graph below is in the public domain and is reasonably well understood, but, as usual, interpretations differ. Pessimistic takes often underestimate increases in quality as well as size. Optimistic takes, however, miss some of the downsides.10 Yes, homes are bigger, but part of the reason has to do with zoning laws that make it easier to get bigger houses for proportionally less money than smaller houses. Many would prefer a smaller house but cannot find one in the area they wish to live in for commuting or safety reasons. When I first moved to Michigan, for example, I lived alone in a three-bedroom house because there were no good one-bedroom houses available near my workplace, and all of the apartment buildings were loud and crime-ridden.

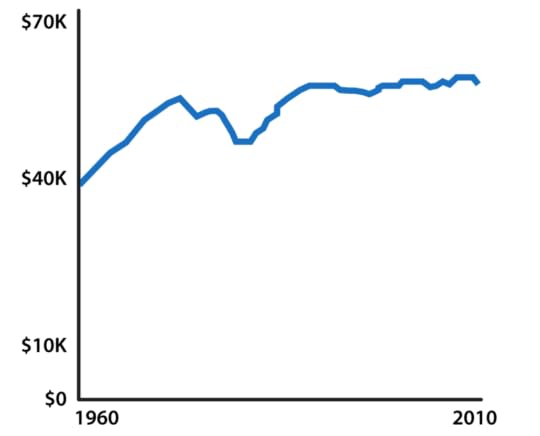

7. U.S. Median Rents (in 2014 dollars)

Source: Apartmentlist

So, once again, would most poor and middle-class Americans rather rent a modern house/apartment, or rent the sort of house/apartment their parents had, but for half the cost?

Infrastructure

The first New York City subway opened around 1900. Various sources list track lengths from 10 to 20 miles and costs from $30 million to $60 million dollars. The variance here has to do with different sources capturing spending at different stages of construction. In any case, the data we have suggest costs of between $1 million to $4 million per kilometer.

Assuming that this estimate is good enough for government work, it looks to be the inflation-adjusted equivalent of roughly $100 million per kilometer today. In contrast, a new New York subway line being opened this year costs about $2.2 billion per kilometer, suggesting a cost increase of twenty times.11

Again, cross-national comparison may help. Paris, Berlin, and Copenhagen subways cost about $250 million per kilometer, almost 90 percent less. Yet even these European subways are overpriced compared to Korea, where a kilometer of subway in Seoul costs $40 million (although another Korean subway project cost $80 million per kilometer).12 This is a difference of 50 times—5,000 percent—between Seoul and New York for apparently comparable services. It suggests that the 1900s New York estimate above may have been roughly accurate if their efficiency was roughly in line with that of modern Europe and Korea.

So, to summarize: In the past fifty years, education costs have doubled, college costs have dectupled, health insurance costs have dectupled, housing costs have increased by about fifty percent, and subway costs have at least dectupled. U.S. health care costs about four times as much as equivalent health care in other “first world” countries; U.S. subways cost about eight times as much as equivalent subways in other “first world” countries.

People may know these numbers, but they seem to underestimate their significance. Some may just laugh it off, remembering how Grandpa used to talk about how back in his day movie tickets only cost a nickel. But all of the numbers cited above are inflation-adjusted. Many costs have really, genuinely dectupled, with no economic or statistical trickery involved.

This is especially strange because, as already noted, improving technology and globalization ought to be reducing costs. And in some respects they have. For example, in 1983, the first mobile phone cost $4,000, or about $10,000 in today’s dollars. (It was also terrible.) Today a much better phone costs only about $100. This is the right and proper way of the universe. It’s why we fund scientists, and pay businesspeople the big bucks.

But college and health care have still had their prices dectuple, and that is despite the obvious inputs of high technology that permeate these service fields. Patients can now schedule appointments online; doctors can send prescriptions by fax; pharmacies can keep track of medication histories on centralized computer systems that interface with the cloud; nurses get automatic reminders when giving two drugs with a potential interaction; insurance companies accept payment through credit cards—and all of this still costs ten times more than it did in the days of punch cards and secretaries who did calculations by hand.

Things are actually even worse than this, because we have many opportunities to save money that were unavailable in past generations. Underpaid foreign nurses immigrate to America and are willing to work for lower wages. Doctors’ notes are sent to India overnight to be transcribed by sweatshop-style labor for pennies an hour. Medical equipment gets manufactured in some labor-cheap third-world country. And it still costs ten times as much as when this was all made in the United States, back when minimum wages were proportionally higher than they are today.

And it’s actually even worse than this. Many of these services have decreased in quality, presumably to cut costs even further. Doctors used to make house calls. Women who gave birth in the hospital used to stay 8 to 14 days in the 1950s but that declined to less than 2 days in the mid-1990s. This isn’t because modern women are healthier; it’s because hospital administrators kick them out as soon as it’s safe, to free up beds for the next person. Historic records of hospital care generally describe leisurely convalescence periods designed to make sure patients felt well before they were let go; now the mantra is to evict people as soon as they’re “stable,” in other words not in acute crisis.

If we had to provide today the same quality of service as in 1960, and without the gains from modern technology and globalization, health care might cost fifty or even a hundred times more. Hardly anyone could afford that.

Why is this happening? The existing literature on cost disease focuses on the aforementioned Baumol effect, which dates from the 1960s. Suppose in some hypothetical economy that people can choose either to work in a factory or join an orchestra, and the salaries of factory workers and orchestra musicians reflect relative supply and demand and profit in those industries. Then the economy undergoes a technological revolution enabling factories to produce ten times as many goods with the same labor input. Some of the increased productivity trickles down to factory workers, and they earn more money. Would-be musicians might be expected to leave orchestra work behind to join much higher-paying factories, and so orchestras would have to raise wages to be assured of enough musicians. So tech improvements in the factory sector raise wages in the orchestra sector.

But this story doesn’t explain the cost disease we observe today; the industries involved generally aren’t paying their workers more! For example, take teacher salaries over time (Figures 8 and 9).

8. Average Salary for Public School Teachers, in 2011 Dollars

9. Average Salary for Public School Teachers, as Ratio of Average Salary for All Full-Time Workers

Source: Fifty-Five Million

As the first graph shows, teacher salaries are relatively flat adjusting for inflation. But salaries for other jobs are increasing modestly relative to inflation. So teacher salaries relative to other occupations’ salaries are declining.

Figure 10 is a similar graph for professors. Professor salaries are rising a little, but they’re probably losing position relative to the average occupation. Also, note that although the average salary of each type of faculty is stable or increasing, the average salary of all faculty is declining. The reason is no mystery: Colleges are switching from tenured professors to adjuncts, who complain of being overworked and abused while making about the same amount as Starbucks baristas, also usually without benefits.

10. Faculty Salaries 1975-2012

Source: Higher Ed Data Stories

This resembles the case of the hospitals cutting care for new mothers. The price of the service dectuples, yet at the same time the service still must sacrifice quality in order to control costs.

Speaking of hospitals, take a look at Figure 11. Female nurses’ salaries went from about $55,000 in 1988 to $63,000 in 2013. This is probably around the average wage increase during that period. Some of this reflects changes in education: In the 1980s only 40 percent of nurses had a degree; by 2010, about 80 percent did.13

11. Nurses’ Annual Salary by Gender, in 2013 Dollars

Source: Journal of the American Medical Association

And now for doctors (Figure 12). The graph again displays apparent stability. But appearances can be deceiving. A lot of doctors’ salaries now go to paying off their ballooning medical school debt.

12. National Peak Physician Income, 1973-1997

Source: The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

Thus, the overall picture is that health care and education costs have managed to increase by ten times without a single cent of the gains going to teachers, doctors, or nurses. Indeed, these professions seem to have lost ground salary-wise relative to others.

Or maybe not. Might total compensation be increasing even though wages aren’t, notably through more generous vacation, maternity and paternity leave provisions, and pensions? It’s an interesting question, but the answer seems to be no. The pensions crisis in plain view, especially for government workers, has more to do with revenue shortfalls than with wildly more generous pensions as of late. In general, pensions aren’t increasing much faster than wages, but this might not be true in all sectors. Still, any effect here is likely marginal.14

And that is not all the bad news for teachers and doctors. Money aside, job satisfaction has plummeted for a variety of other reasons—not all of which are unrelated, possibly, to cost disease. Veteran teachers and doctors alike regularly complain that their jobs used to be enjoyable and fulfilling, but now they feel overworked, unappreciated, and perhaps above all, trapped in mountains of paperwork—in increased transactional costs.

It might make sense for these fields to become more expensive if their employees’ salaries were increasing. And it might make sense for salaries to stay the same if employees instead benefitted from lower workloads and better working conditions. But neither of these things is happening.

Clearly, the Baumol effect by itself has its limits as an explanation for cost disease. So what else might be going on?

Let us first consider the possibility that all of this is an illusion. Maybe adjusting for inflation is harder than we think. Inflation is an average, after all, so some sectors must manifest higher-than-average inflation—maybe education, health care, housing, and infrastructure. Or maybe the raw data is badly defective.

But it’s not likely. An acquaintance runs a private school that does just as well as public schools, for an average cost of only $3,000 per student per year, a fourth of the public school rate. Economist Alex Tabarrok notes that India has a private health system that delivers the same quality of care as its public system for a quarter of the cost.15 Whenever the same drug is provided by the official U.S. health system and some kind of grey market, the grey market supplement costs between a fifth and a tenth as much; for example, Google’s first hit for Deplin®, the official prescription for L-methylfolate, shows a cost of $175 for a month’s supply; unregulated L-methylfolate supplement delivers the same dose for about $30. And this doesn’t even take into account things like a $1 bag of saline that costs $700 at hospitals.16 Since it is not remotely difficult to cite examples of doing things for a fraction of what we usually pay, we should not be reluctant to believe that the cost of nearly everything really has risen and is still rising.

If so, this might suggest that markets are not working because of massive rentier behavior that enables the fortuitously positioned to increase costs without suffering any decreased demand. Certainly markets for medicine and education are deeply distorted by the paucity of information in some cases and by the distortions of regularized third-party payments in others. But we need to think of the rentier phenomenon not in the old way, as the work of individuals at market choke points, but rather as institutions performing the same kind of distortion.

Still, even market-immune institutional price-gouging cannot explain cost disease entirely. For one thing, corporate profits haven’t increased nearly enough to account for where all the money is going. For another, non-profits live a more complex life. Take increasing college tuition costs. Some of it is the administrative bloat we would expect. But some of it is fun “student life” types of activities like clubs, festivals, and paying Milo Yiannopoulos to speak and then cleaning up after the ensuing riots. These sorts of things arguably improve the student experience, but the typical student might not prefer an expensive college with clubs/festivals/Milo than a cheap college without them. More important, however, the typical student is rarely offered this choice without it being attached to a prestige damper.

So suppose it were proved that Khan Academy could teach you just as much as a normal college education, but for free. People would still ask whether employers would accept a Khan Academy degree, whether it would look good on a resume, whether people make fun of Khan Academy grads. The same is true of community colleges, second-tier colleges, and for-profit colleges. If prestige and its prospective uses are more important to many people than education per se, why can’t colleges just charge whatever they want irrespective of most normal market considerations?

This suggests that institutional rentier price-gouging may at times be indirect or socially mediated—and that it may come down to how service “products” are packaged. For example, many hospitals have switched from many-people-in-a-big-ward to private rooms. Once again, as with bells-and-whistles university campuses, the choice between expensive hospitals with private rooms versus cheap hospitals with roommates is not on offer. Perhaps more labor-intensive service industries have their own reasons for switching to more-bells-and-whistles services that people don’t necessarily want, and consumers just go along because for some reason (lack of information transparency, possibly) they’re not exercising choice as they would in other markets.

Some examples brought above may suggest that, as libertarians like to claim, government is inherently inefficient relative to private industry. Government handles most primary education and subways, and has its hand deep into health care. But for-profit hospitals aren’t much cheaper than government hospitals, and private schools usually aren’t much cheaper (and are sometimes more expensive) than government schools. And private colleges cost more than government-funded ones. So even if this general argument about government is right, it isn’t right in the cases where the worst problems with cost disease exist.

But maybe we can indict government in some other way: for example, regulation, which public institutions and private companies alike must deal with? This seems to be at least part of the story in health care, given how much money you can save by grey-market practices that avoid the FDA. It’s harder to apply it to colleges, though regulations like Title IX do affect costs in the educational sector.

This claim raises the general question of whether deregulation dampens cost-curve increases. Libertarians and most garden-variety conservatives say it does. It is hard to know: despite the supposed war on overregulation Republicans (and Democrats in some sectors) waged in the 1980s and 1990s, the number of pages in the Federal regulatory code continued to increase.

13. Total Number of Pages in the Code of Federal Regulations, 1975-2011

Source: Mercatus Center, George Mason University

Maybe the Trump Administration’s determination to deconstruct the administrative state will produce a different outcome. But it still may not affect cost disease very much. Consider pet health care, which is a much bigger business in the United States than most people realize. Veterinary care is much less regulated than human health care, yet its cost is rising as fast (or faster) than that of the human medical system.17 It’s hard to know what to make of this, except to say that sometimes demand is whimsical, and whimsy can end up being expensive.

There is yet another way to think about increased regulatory complexity: it happens not only through literal regulations, but also through fear of lawsuits. Institutions sometimes add extra layers of administration and expense not because they’re forced to, but because they fear being sued if they don’t and something goes wrong.

This happens all the time in medicine. A patient goes to the hospital with a heart attack. While he’s recovering, he tells his doctor that he’s upset about all this. Any normal person would say, “You had a heart attack, so of course you’re upset; get over it or you might cause yourself another attack.” But if his doctor says this, and then a year later the patient commits suicide for some unrelated reason, his family can sue the doctor for “not picking up the warning signs” and win millions of dollars. So the doctor holds his tongue and instead brings a psychiatrist into play, who does an hour-long evaluation, charges the insurance company $500, and determines using his or her immense clinical expertise that the patient is upset because he just had a heart attack.

Those outside the field of medicine have no idea how often this sort of thing happens. People often say that the importance of lawsuits to medical cost increases is overrated because malpractice insurance doesn’t really cost that much, but the situation described above would never look lawsuit-related. There is so much anticipatory protection going on that it has gotten baked into professional realities. This has nothing to do with government regulations (except insofar as regulations make lawsuits easier or harder to bring), but it does drive cost increases, and a similar dynamic might apply to fields outside medicine as well.

Broader social trends may have something to do with all this, as well. Perhaps our tolerance for risk has changed. In other words, maybe what people are prepared to spend to mitigate risk is due less to a fear of being sued than to really caring more about whether or not people are protected. Playgrounds are changing because modern parents won’t let kids run around unsupervised on anything with sharp edges. Suppose that one in 10,000 kids suffers a serious playground-related injury. Is it worth making playgrounds cost twice as much and be half as fun in order to decrease that number to one in 100,000? This isn’t a rhetorical question; different people can have legitimately different opinions here.

Moreover, there is probably a difference between personal versus institutional risk tolerance. Every so often, an elderly person walking to the bathroom will fall and break a hip. This is a fact of life that the elderly deal with daily. Yet few elderly people spend thousands of dollars fall-proofing the route from their bed to their bathroom, or hiring people to watch them to make sure they don’t fall, or buy a bedside commode to make bathroom-related falls impossible. This suggests a revealed preference that the elderly are willing to tolerate a certain fall probability in order to save money and convenience.

But hospitals, which face huge lawsuits if any elderly person falls on the premises, are not willing to tolerate that probability. They put rails on elderly people’s beds, place alarms on them that will go off if the elderly person tries to leave the bed without permission, and hire patient care assistants who, among other things, go around carefully holding elderly people upright as they walk to the bathroom (I assume this job will soon require at least a master’s degree). As more things become institutionalized and the level of acceptable institutional risk tolerance sinks, the cost-risk tradeoff could shift upwards even if there isn’t a population-level trend toward more risk-aversion.

Then there is the cost of delinquency. Might things cost more for the people who pay because so many people don’t pay? This is somewhat true of colleges, where an increasing number of people are getting in on scholarships funded by the tuition of non-scholarship students. And everyone knows that student-loan interest rates are higher because of a pretty high default rate.

Delinquency also applies in health care. Hospitals complain of “frequent flier” patients who overdose on drugs on a near-weekly basis. They come in, get treated (hospitals can’t legally turn away emergency cases), get advised to get help for their addiction (without the slightest expectation that they will take the advice), and then get discharged. Most of them are poor and have no insurance, but each admission costs several thousand dollars, which is eventually paid by a combination of taxpayers and other hospital patients with good insurance who get big markups on their own bills.

The Politics of Cost Disease

Libertarian-minded people keep talking about how there’s too much red tape and the economy is being throttled. And less libertarian-minded people keep interpreting that line as not caring about the poor, or not understanding that government has an important role in a civilized society, or as a “dog whistle” for racism. This discourse might improve if most people realized that some of the most important industries cost ten times as much as they used to for no obvious reason, plus they seem to be declining in quality, and nobody knows why. State that clearly, and many of our political debates are bound to appear in a different light.

For example: Some promote free universal college education, remembering a time when it was easy for middle-class people to afford college if they wanted it. Others oppose the policy, remembering a time when people didn’t depend on government handouts. Both statements are true. Lots of people paid for tuition at good colleges just by working summer jobs, which was not hard to pull off when college cost a tenth of what it does now. The modern conflict between opponents and proponents of free college education is over how to distribute our losses relative to the time before the ravages of cost disease. In the old days, we could combine low taxes with widely available education. Now we can’t because core things have become too expensive, and so we argue about which value to sacrifice. If we could figure out the causes of cost disease and reverse it, we wouldn’t need to have that argument.

Another example: Some get upset about teachers’ unions, saying they must be sucking the “dynamism” out of education because of increasing costs. Others defend them, saying teachers are underpaid and overworked and that without unions things would be even worse. Once again, in the context of cost disease, both are obviously true. Taxpayers are trying to protect their right to get their children an education as cheaply as their own. The teachers are trying to protect their right to make as much money as they used to. Again, the conflict is about how to distribute relative losses; somebody will be worse off than they were a generation ago, so who’s it going to be?

The same is true to greater or lesser degrees in the various debates over health care, public housing, public transportation costs, and so on. Imagine that the price of clean, fresh water were to dectuple. Some people would have to choose between drinking and washing dishes. Activists would argue that taking a shower is a basic human right, and grumpy talk show hosts would point out that in their day, parents taught their children not to waste water. A coalition would promote laws ensuring government-subsidized free water for poor families; a Fox News investigative report would show that some people receiving water on the government dime are taking long, luxurious showers. Everyone would get angry, but this would all be secondary to the fact that water costs ten times what it used to, for no obvious reason.

Think about what a reversal of cost disease might do in (for example) health care. How many people currently opposed to paying for universal health care would be happy to pay for it if cost a lot less, was less wasteful and more efficient, and its prices were expected to go down rather than up with every passing year?

Similarly, if government found a way to give people “free” college tuition for about $1,000 a year, and decent housing for only about half of what it costs now, that would be the greatest anti-poverty advance in U.S. history. That program is called “having things be as efficient as they were a few decades ago,” when poverty by any objective standard did plummet.

More generally, GDP per capita in the United States is now four to five times larger in constant dollars than it was in about 1950, yet most Americans still work forty-hour weeks, and some large-but-inconsistently-reported percent of Americans still live paycheck to paycheck. Some of this is because expected minimal standards of living have risen sharply, and some of it, more recently, is because most of the gains in the economy have gone to the rich who benefit from greater returns to invested capital. But some of it, maybe much of it, has to do with cost disease—with some concatenation of elusive structural changes within society that ramify throughout the economy and that are much worse in the United States than in other advanced countries.

Not everybody understands all of this, but intuitions often hit home. People sense that when the cost of basic human needs goes up faster than wages—when, even if your household is bringing in twice as much money as before, your health care and education cost ten times as much—you’re falling behind. If we don’t figure out what is really causing cost disease, and find a way to stanch and reverse it, the future of American politics may not get much better from here.

1Edward N. Luttwak, “Breaking the Bank,” The American Interest (September/October 2007).

2Warren Fiske, “Brat: U.S. school spending up 375 percent over 30 years but test score remain flat,” Politifact, March 2, 2015.

3“Summary of Major Findings in Long-Term Trend Assessments, 2012,” The Nation’s Report Card.

4See Scott Alexander, “Contra Robinson on Schooling,” Slate Star Codex, December 2, 2016; “Highlights from the Comments Thread on School Choice,” Slate Star Codex, December 4, 2016.

5“Table 320: Average undergraduate tuition and fees and room and board rates charged for full-time students in degree-granting institutions, by type and control of institution: 1964-65 through 2006-07,” Digest of Education Statistics, National Center for Education Statistics.

6Paul F. Campos, “The Real Reason College Tuition Costs So Much,” New York Times, April 4, 2015.

7Chris Conover, “The Cost of Health Care: 1958 vs. 2012,” Forbes, December 22, 2012.

8Some use this data to argue for the superiority of centralized government health systems, although the blog Random Critical Analysis has an alternative perspective. See “US life expectancy is below naive expectations mostly because it economically outperforms,” Random Critical Analysis, November 6, 2016.

9See Robert H. Brook et al., “The Health Insurance Experiment: A Classic RAND Study Speaks to the Current Health Care Reform Debate,” RAND Corporation, 2006; Katherine Baicker et al., “The Oregon Experiment—Effects of Medicaid on Clinical Outcomes,” New England Journal of Medicine, May 2, 2013.

10For example: Mark J. Perry, “Today’s new homes are 1,000 square feet larger than in 1973, and the living space per person has doubled over last 40 years,” AEI, February 26, 2014.

11Matt Yglesias, “NYC’s brand new subway is the most expensive in the world—that’s a problem,” Vox, January 1, 2017.

12Alon Levy, “Comparative Subway Construction Costs, Revised,” Pedestrian Observations, June 3, 2013.

13“Nursing Fact Sheet,” American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

14Lawrence Mishel, “Professor Hubbard’s Claim about Wage and Compensation Stagnation Is Not True,” Economic Policy Institute, July 4, 2015.

15Tabarrok, “Private versus Public Health Care in India,” Marginal Revolution, December 6, 2016.

16“The secret of saline’s cost: Why a $1 bag can cost $700,” Advisory Board, August 27, 2013.

17Liran Einav, Amy Finkelstein, and Atul Gupta, “Is American Pet Health Care (Also) Uniquely Inefficient?” National Bureau of Economics Research, September 2016.

April 10, 2017

Iran Set to Receive First American Aircraft Since 1979

Iran may be set to receive two Boeing 777s as early as this month, the first American-made aircraft delivered to Iran since the fall of the Shah in 1979. As Reuters reports:

IranAir may get its first new Boeing jetliner a year earlier than expected under a deal to take jets originally bought by cash-strapped Turkish Airlines, Iranian media and industry sources said.

Iran had been expected to receive the first of 80 aircraft ordered from the U.S. planemaker in April 2018, but at least one brand-new aircraft is reported to be sitting unused because it is no longer needed by the Turkish carrier.

Industry sources said Boeing was in negotiations to release at least one 777-300ER originally built for Turkish Airlines, which is deferring deliveries due to weaker traffic following last year’s failed coup attempt in Turkey….

Iran’s Deputy Roads and Urban Development Minister Asghar Fakhrieh-Kashan told the semi-official Mehr news agency the first Boeing 777 aircraft would reach Tehran within a month.

If confirmed, the deliveries would be months ahead of schedule for the $16.6 billion deal signed between IranAir and Boeing in December. Replacing its outdated commercial aviation fleet has been a priority for Iran since the end of nuclear sanctions under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (the Iran nuclear deal). Iran has signed a flurry of deals with Boeing, Airbus and other western aircraft manufacturers worth tens of billions of dollars. Combined with other big ticket items, most notably energy and energy infrastructure deals, proponents of the nuclear deal both inside and outside Iran hope that increased economic ties will lock-in the Trump administration and other nuclear deal skeptics.

The only good news for opponents of the nuclear deal is that so far foreign corporations have been hesitant to actually enter the Iranian market, limited in particular by banking restrictions and other regulatory obstacles. But as these Boeing deliveries show, the countdown to Iran’s full re-emergence into the global market may be starting to tick faster.

US Energy Emissions Keep Falling

America’s carbon emissions dropped three percent last year, a significant dip that came to us courtesy of—you guessed it—the shale boom. Cheap, abundant natural gas displaced coal as America’s top power source, and in the process got rid of the copious sooty local air pollutants and greenhouse gas emissions that those coal plants spew (natural gas burns roughly half as much CO2 as coal). New data from the Energy Information Administration shows that U.S. energy-related emissions fell 1.7 percent:

U.S. energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2016 totaled 5,170 million metric tons (MMmt), 1.7% below their 2015 levels, after dropping 2.7% between 2014 and 2015. These recent decreases are consistent with a decade-long trend, with energy-related CO2 emissions 14% below the 2005 level in 2016.

That’s right: over the past 11 years, energy-related carbon emissions have plummeted 14 percent. Greens will want to credit their darlings, wind and solar power, but those energy sources (zero emissions as they may be) still only make up 5.6 percent and 0.9 percent of U.S. power production, respectively. It’s not a coincidence that the biggest shift in the American energy landscape—the shale boom—has coincided with this drop in emissions. Bargain-priced natural gas is making the U.S. a global green leader.

But perhaps more significantly, the country is growing greener by getting more efficient. Carbon intensity, a measure of how much carbon dioxide is emitted per unit of economic activity, has been falling of late: it dropped 3.3 percent in 2016, and 5.3 percent the year before that. This lets us have our cake and eat it, too, in other words.

Environmental progress doesn’t need to come at the cost of economic growth, and in fact when those two goals clash, it’s environmental policies that are often first forgotten. Smart greens know that the best way to achieve their stated aims is to back strategies that wed growth with better environmental stewardship. Hastening the shift to a less carbon intensive information economy is one example; fully embracing the shale energy revolution and all of the green benefits it entails is another.

Whether greens get on board or not, American emissions are dropping even as the economic grows, and for that, we have fracking to thank.

Khan Sheikhoun, Shayrat Air Base, and Now What?

I wrote my first response to the U.S. cruise missile attack on Shayrat Air Base on April 7, 2017, at 2:30 p.m. EDT—in other words, about 18 hours after the attack. A great deal more has happened since, and it is in the nature of a crisis that this be so. One of the characteristics that make a crisis a crisis is that decision-makers on all sides enter into a condition of accelerated experience. Time pressure deepens, and uncertainties loom. Emotions roil. Stuff happens in parallel (Washington, Damascus, Moscow, Tehran, elsewhere) that somehow seems to collide, upsetting the normal laws of political physics. This is one reason crises are so accident-prone historically. People do stupid things they probably wouldn’t do in normal times, although in the case of the current President and Secretary of State, one cannot be too confident about that, their experience levels being so very, very low.

What you will see below in italics is my original text, and interpolations, corrections, and expansions within and around it in this normal text. After all, analysts outside of government experience some of the pressures of crises, too. I thought at least some readers would like to be let in on that how that process goes.

Before beginning in earnest, we can sum up what we know now, Monday morning, that was not so clear, to me at least, this past Friday afternoon. So the Obama Administration declared a red line concerning the use of chemical weapons and then failed to enforce it, but the Trump Administration did not declare such a red line but enforced it anyway. Which is worse? The former is worse because it trashes U.S. credibility, but the latter is not wonderful either because it confused everyone, a situation that can be accident-prone as well. But then, just a short time later, Secretary Tillerson, Moscow-bound tomorrow, demanded that the Russian government stop supporting Assad. This amounts to drawing another red line that will not—cannot—be honored except at excessive risk or cost. This was a stupid thing to say, akin to the Soviets or Chinese demanding in 1967 that the U.S. government stop supporting South Vietnam.

That is not all—see below.

By now the world knows that U.S. military forces for the first time since the onset of the Syrian civil war in 2011 have attacked regime targets. Plenty of the basic facts are known about what transpired about 18 hours ago, but a few important ones are not—at least not in the public domain.

For example, we have only a very general BDA (Bomb Damage Assessment) report. This matters because Tomahawk cruise missiles are very accurate if “lite” weapons. Knowing what the four dozen or so—59 as it turned out—missiles hit and missed, deliberately and otherwise, could tell us a lot about why the President, presumably with Secretary of Defense James Mattis’s guidance and concurrence, chose the lesser of three options presented at what has been described as a meeting of considerable length. That in turn could tell us if the intention ultimately is to coerce the Russians into coercing the Syrians to stop doing monstrous things to their own people, and possibly coercing them to support a compromise political settlement to the war; or if it’s just an Eff-You gesture designed only to relieve the sudden pressure of moral unction that unexpectedly came upon our new Commander-in Chief—who seemed to lurch from coldblooded Randian to Godtalk invoker of the American Civil Religion in the wink of an eye. In other words, knowing more about the target set would tell us whether there is any political strategy attached to the use of force, or not. Probably not.

This question has since been answered, in a most foolish way. The Administration made it clear in public that the attack was a “proportional” one-off, a kind of messaging signal, and would not be repeated if the Syrians now behaved themselves. Even if this is what you intend, saying so is unhelpful, to say the least.

I mentioned Vietnam a moment ago. One of the problems with U.S strategy in that war during the Johnson Administration (Lord knows there were many) is what came to be known as “graduated response.” That was a then-popular game-theoretical term for the use of proportionate military action as a messaging device. Jim Mattis knows this. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara thought this was terribly clever, very much best and brightest. It wasn’t, and Jim Mattis knows that too. Graduated response left the initiative in determining the level of violence to the enemy, and in a situation (like Vietnam and Syria) where the balance of interests trumps the balance of power, the local party willing to sustain the most pain in what it considers to be an existential engagement will gain an advantage. So we have ceded advantage in the next move to the Syrians, with their Russian lawyers close at hand.

And sure enough, within 24 hours after the strike we heard news of a Syrian chlorine gas attack in a Damascus suburb called Qaboun. No, this was not sarin, and no this was not dropped from an aircraft, and no this did not murder scores of non-combatants. But it was surely deliberate: This was Bashir al-Assad’s way of saying “eff you” back at us and starting a nasty game of finding our threshold for a repeat attack. If he acts now as he has acted many times before, Assad will ratchet up the stakes, looking for the level just below our response trigger. Hence I wrote:

Additionally, we do not know if other U.S. forces are flowing to theater, and which forces they may be—so we don’t know if yesterday evening’s strike was intended to be a one-off or the start of a larger campaign. Careful: It could be both a one-off designed to send a message but not to reshape policy unless some other actor—the Syrian regime, the Russian regime, even the Iranian regime—acts in such a way as to “inspire” further U.S. kinetic exercises. But since that sort of response is entirely possible—most obviously, if Assad uses sarin again and dares us to escalate to stop him, accepting much more risk in the process—we had better be prepared for the move after next if there is one. If we are not preparing, we make that move more likely, and exacerbates the potential vulnerability the strike has set in motion.

Yes, and again: That is why declaring that we were done shooting was an error. I find it perplexing that Secretary Mattis did not prevent that error, since his knowledge of history certainly furnishes all the reasons anyone needs to have avoided it.

Nor, very much related, do we know if Syrian or more likely Russian aircraft or ships have moved toward U.S. Navy forces in the Eastern Mediterranean. That would be normal. Adult militaries scout and monitor each other’s protocols just like serious athletes scout and study their rivals before the game. (In this case, not only U.S., Russian, and perhaps Syrian and Iranian militaries are trying to listen and learn, but so most likely are Israeli and Turkish militaries.)

Less that an hour after I wrote this paragraph, and even before it could be posted, news broke of a Russian missile frigate sailing into the Eastern Mediterranean. OK, so that box got checked in a hurry.

But sometimes monitoring behavior can become aggressive and inspire concerns about fleet defense, for creating an air of uncertainty is often a tempting gaming tactic at a moment like this. But it can backfire if uncertainty produces bravado or panic—which can amount to more or less the same thing. It’s happened before, many times. It would be not so good, for example, if the U.S. Navy were to shoot down a Russian warplane buzzing too close to our intell ship that is sailing along with the USS Ross and the USS Porter. (I don’t know its name, but I’m pretty sure there is one nearby.)

That did not happen, which is good. The Russians are not going to risk World War III over Syria. We were pretty sure of that before, and now we’re surer. The Russians telling us how we’ve harmed U.S.-Russia relations at the start of this Administration is actually a good thing, too. It’s an honor to be disliked by the right kind of people, after all, and now the President knows better what kind of people these guys really are. We avoided Russians and sarin stocks at Al-Shayrat, which means we knew they were there—the Russians and the sarin—which means, more importantly, that we know the Russians know what the Syrians are doing. Tillerson said that the Russians are either “incompetent or complicit” in the CW attacks, but he has to know that it’s the latter. I hope he gets a chance to make that clear in private tomorrow in Moscow. If he leaves in a huff, that would not be so bad either.

Now think what this means in a broader sense. If the Putin regime thought it was doing itself a big favor by trying to get Trump elected, it now needs to rethink that. I doubt that the Russians though he would win, so that they did not think their normal electoral-interference shenanigans would make a difference. Just goes to show that other governments do stupid things, too. And while hardly anyone agrees with me, I still think that the Russian government’s over-the-top reaction to the Navalny-inspired protests of recent days was inspired by its huge fear of a genuine populist movement such as the ones Trump and Le Pen represent—and the Russians gave her party money, too!

Meanwhile, on our side of the fence, there is a chance now that the President will rethink what the Russians have been up to in Ukraine and elsewhere, and maybe even what NATO is still good for. There is a tendency for political and geostrategic novices to say all sorts of idiotic things about subjects they don’t really understand, and then once they are forced to understand them the idiocy mostly goes away. This has happened many times before. I liken this to pouring all sorts of stuff into the top of a funnel, but only the little, far more predictable stuff comes out the bottom: This is the funnel as a metaphor for how reality shapes on-the-job-training thinking. Lots of U.S. foreign policy has been bending back to the mean, for good or ill, since January 20—although a certain amount of damage has already been done.

There is plenty more we don’t yet know, but of an entirely different order. Most of us remember the bizarre sequence of events back in 2013 when, after a Syrian regime chemical weapons attack on unarmed civilians President Obama prepared a strike and then backed off, allowing the Russians to fish him out of the drink with a false promise about ridding Syria of all its chemical munitions. The Syrian declaration was false, the Russians knew it was false (for the Soviets had supplied most of the stuff and the expertise regarding how to use it, and were well aware of what the Syrians really had by way of chemical precursors and weapons), and they made a safe bet that an avariciously political but very rise-averse Obama Administration would be willing to take the declaration at face value so as to crow about its own success.

The process to get there, recall, was truly wild: The decision system worked perfectly until the President changed his mind after a garden walk with one of his political aides, not consulting his Secretaries of State and Defense and wrongfooting his own National Security Advisor as she was about to make a speech supporting the military strikes. Until the sarin settled over Khan Sheikhoun on Tuesday, some of Obama’s staunchest defenders were still claiming that all of Syria’s chemical arsenal had been removed without a shot being fired, completely oblivious to the logic and mounting evidence that they had in fact been snookered.

Remember all that? Well, how does what has now happened in this new Administration differ? Note that just a few days before the Khan Sheikhoun attack, both Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and UN Ambassador Nikki Haley had said that dealing with Bashar al-Assad and his merry band of mass murderers was “not a priority.” So, hearing that, Assad thinks, reasonably enough, “Well, I can do what I like now,” and the Russians say “amen.” So Assad proceeds to terrorize a corner of Idlib province, the obvious next regime target after the fall of Aleppo. The aim? Same as before: ethnically cleanse to the extent possible a stronghold of Sunni Arabs and send them into refugee columns headed ultimately for Europe, the better to serve a host of Russian interests in the process.

But then suddenly the Americans do a volte-face: They change their minds and attack with cruise missiles. They must have realized in Damascus just how the North Koreans felt in June 1950, just weeks after Dean Acheson drew his infamous line putting South Korea outside the U.S. defense perimeter for mainland Asia: They take high U.S. officials at their word, only to find that our word won’t stand against the first rush of righteous indignation we summon.

That’s not all. Apparently, if one can believe the news, the President worked mainly through General Mattis and, one supposed, General McMaster because he’s just down the hall. It’s not clear if Secretary Tillerson knew about the decision until after it was taken. We apparently warned the Russians to stay clear though the deconfliction channel before the strike, and with Tillerson headed off to Moscow in a few days one would think he would have been part of that judgment. But it’s not at all clear that he was.

Well, thanks to some sharp and believable reporting in the New York Times, we now have a much better assessment of the decision process. There is good news and other news. Tillerson was in on the process, it seems, but whether he was an active or inert ingredient in the recipe that led to the strike is still unclear. The other problem is that, while the Deputies Committee convened properly, created options, which then went to the NSC or the Principals Committee (that’s how things are supposed to work), some of these meetings were by secure telecom methods. The President was either aboard Air Force One or in Florida, and most of the rest of the NSC was in Washington. This is better than not using the process at all, but telecom methods almost always lose something in translation—body language, paralinguistic cues, and more. It often means that the people who are physically near the President have more sway with their advice than those far away—which is another reason why overuse of the “Florida White House” is such a bad idea.

So what is one to make of an Administration that seems just as prone to monkey-in-the-machine-room process antics as its predecessor, and that also chose the least risky option under the circumstances?

Yes, there is a difference between old and new Administrations—of course. Trump acted quickly; Obama deliberated over such matters endlessly. Trump comes across more like Henry IV, Obama more like Hamlet, if you like a Shakespearean metaphor. And the circumstances have changed: This second time around with Assad and his chemicals there was really no way to duck a reckoning. As many have pointed out—both Democrats who rued Obama’s passivity in the past as well as Republican supporters of Trump right now—if the U.S. government had again failed to act in the face a raw violation of international norms and treaty obligations, then the message to bad actors everywhere would have been, in essence, “Do as you please to anyone you please to do it to, because no one in the civilized world will lift a finger to stop you.”

I still on balance concur with the decision to strike, but that’s because there is a history here that even a new Administration simply cannot ignore. We needed to restore some confidence in U.S. verve. We have allies as well as adversaries, and they need to know that the superpower they rely on en extremis will protect its clients, or all sorts of nasty things can happen that will ultimately affect us. That’s why it’s called an “order.” That’s why when Senator Paul criticized the strike saying that the Syrians “did not attack the U.S.,” he sounded just as foolish as he is.

That said, as long as there is no political purpose attached to the use of force it looks to others like the United States is still acting as a cross between a self-appointed global policeman and the mother-in-law of the world, lecturing others about their supposed moral frailties. If the situation with the attack on Khan Sheikhoun had been historically virginal, a good case could have been made for not using force. And if that had been the case, I would not criticize Senator Paul by name. But it wasn’t so I am.

As things stand, however, the Administration chose the least aggressive, most risk-averse military option put before it, so it not clear how loud and strong a message it has sent. That is why a new cycle of taunt and bitchslap may ensue, with unpredictable consequences. But what were the other two options the President heard from his military advisers?

Yes, see above. So was this strike a pinprick or not? I’d say so. The strike did not hit a major Syrian operational center, and it did not destroy more than a quarter of the capacity of al-Shayrat Air Base. It did not, as noted, attack the sarin stocks, because we did not want to create a lethal cloud that could have killed thousands of people instead of, reportedly, just 15. So, again noting earlier comments, what we did may indeed commence a dialectic of taunt and slap, but under conditions that either cede initiative to the Syrians or that needs to run risks of breaking that pattern. Ah, but those other options? Not so attractive, for reasons former President Obama well understands.

I don’t know, of course, nor does anyone not privy to the discussions. But I can guess. One, now favored aloud by Senators McCain and Graham, would be to smash the Syrian Air Force in its entirety, so that no more attacks of the sort we saw this past Tuesday can again be mounted. That would force the Russians to do these kinds of crimes directly, something they may not be willing to do; if they were willing, it would add mass murder to their well-practiced mendacity, which would at the least have a clarifying purpose, not least in the President’s own peculiar head.

But to achieve that aim would require aircraft, not cruise missiles. We would have to suppress Syrian air defenses first to do that, and we might find the deconflict channel with the Russians not nearly clear enough to avoid direct engagement with them. That would really get us into a war, slippery slope and all, and possibly not just with the Syrians in Syria. That sort of thing could touch off, say, little hybrid Russian-speaking green men crossing into Latvia or Estonia, stunning a disheveled NATO with a choice it is now very ill-suited to make.

But we’re not going to be able to coerce the bad actors here into compromise, if not submission, with anything less than more skin in the game. So again, looking at the current diplomatic void, we confront the problem of connecting military action to political objectives that are both desirable and achievable. As it has been from the start, that is very hard to do in Syria, and it may not be worth the risk now that the risk is considerably greater than it was in 2013.

And this is why Syria has always been a hard case that has only gotten harder over time. I do think President Obama is guilty of some misjudgments erring on the side of both safety and passivity, but I never claimed before and I don’t claim now that he was in anyway derelict in his duty as Commander-in-Chief. This has always been hard—a 51-49 percent kind of deal. And that same degree of difficulty is what led the Trump Administration to do the least it felt it could do: Use standoff weapons to “degrade” but not destroy the ability of the Syrian regime to repeat its war crimes.

Many have asserted since Friday that if we want to drive the Syrian cauldron toward a political settlement, we have to torque the battlefield situation in a way to make that necessary. How? And so the old nostrums come back: Arm the Syrian opposition, create no-fly zones, and all the rest. And with the nostrums come all the reasons why these options are hard (or impossible) to do, and may well impose costs not worth the potential payoffs. Syria is still hard, and having a new Administration changes that not one iota.

The uppermost violent option may have been essentially regime decapitation. We have bombs, called Moabs (follow-ons to the Daisy Cutters of old), just one of which can incinerate several square blocks of downtown Damascus—most of the regime’s political and military elite with it—quicker than you can say “pass the humus.” But then we create a vacuum that would probably change the civil but not end it. ISIS is no longer in a position to easily fill such a vacuum, but it is not clear who could or would, the non-salafi rebels being still, after all these years, far from a unified political force. Creating massive state failure by decapitating the Alawi regime would beg some outside power to intervene to suffocate the next pulse of violence, minister to the needy, rebuild governance structures of some kind, and babysit the whole arrangement for many years until it could stand on its own. There are no candidates able and willing to do that as far as I can see, and General Mattis knows this well even if Donald Trump does (or did) not.

I don’t know if this third “big” option is the one the press reports indicate was discarded early on, leaving the planning to flesh out just two options. But I think it was. There is always a “too big” option presented by the military planners in order to make the “middle” option seem more attractive. It’s the same logic that leads retailers to price some items very, very high so that buyers will create an excuse to purchase the next least expensive—but still pretty expensive—item. Works often—but not this time.

Hence, option 1: Shayrat air base, and (hopefully) let’s go home. Well, we’ll soon see about that.

Amen. Yes we will.

A fair bit has been made already about the signaling significance of the strikes against Syria on China and North Korea, as well as other interested parties in East Asia. Some even suppose that a main reason for the strike was to persuade China to coerce North Korea, in its own enlightened self-interest, so that we won’t have to coerce North Korea with very muscular kinetics ourselves a few months down the road. Breaking the news of the strike to the Chinese leader over dinner down in Florida has struck some observers as worthy of Don Corleone himself.

This is a bit much. Yes, a real test of American statecraft is at hand, and so may be a real test of the U.S. military: No U.S. Administration can let the loonies in Pyongyang deploy a nuclear weapons arsenal capable of attacking the U.S. mainland, and they’re getting too damned close. (Some would say, and have said, we should have forced a showdown much earlier, before the North Koreans could credible menace Japan and thus weaken U.S.-Japanese ties.) So a signal of resolve can’t hurt.

But choosing the mildest of one’s options also can’t help very much. You cannot bag big game with a pea-shooter—it’s really as simple and basic as that. Besides, the U.S. government has been down this road before with China, trying to solve North Korea via the dynamics of the Sino-American relationship. We tried it, for example, in 2005 around this same time of the year. I know; I was there. It was clever and logical—and it didn’t work. Maybe it’ll work this time, with a different Chinese leadership and a more advanced North Korean threat to everyone. But if it does, or doesn’t, this jab to Syria will not make a big difference one way or the other.

Finally for now, a wider observation that may elide on our future. A first crisis in an Administration’s life—which this approaches—is a shaping event. It shapes personal and process relationships, and it shapes in particular the inner confidence (or lack thereof) of the President. With this President, no one knows exactly what this might mean, for this President has less experience of governing and geopolitics than any President in American history. We are extraordinarily fortunate, therefore, that next to the most encyclopedically ignorant and temperamentally unsuited President ever to enter the Oval Office are two of the best-suited aides—Generals Mattis and McMaster—one can think of. Both of them know the political limits of the use of force, and the dangers of sloppy thinking applied thereto.

When I say fortunate, I really mean it. It is not too hard to imagine a situation—like one from just a few weeks ago, in fact—in which a Michael Flynn as National Security Advisor and a Steve Bannon still sitting on the National Security Council would push a novice President, now full of himself with a delusional sense of heroic boldness, into doing really dangerous things. One almost wants to thank Bashar al-Assad that he waited a few weeks before committing his latest war crime.

I have little to add to this text except to note that, from this experience, we have at least learned that the President has a heart. That was not entirely clear before. But his heart was evoked by what used to be called “the CNN effect”—the emotional change one gets from pictures. This is indeed the television presidency. And it is still not a good thing for the Commander-in-Chief to be influenced overly much, as clearly seems to be the case, by what he sees on television, especially in a case where there is no habit of deep reading to mitigate the emotional floods thus unleashed. Hence I stand by even more firmly my earlier conclusion:

Everyone smiles when Otto von Bismarck’s old saw about God protecting drunks, fools, and the United States of America is hauled out. It’s just a joke, just a bit of semi-literary wit and harmless humor, right? Or is it?

Barbaric Bombings in Egypt Targets Copts, Sisi

ISIS has claimed responsibility for a pair of suicide bombings at Coptic churches in Alexandria and the Nile Delta city of Tanta during Palm Sunday services. As Egypt’s Al Ahram reports:

On Palm Sunday morning, a bomb exploded inside Mar Girgis Church in the Delta city of Tanta, killing at least 27 and injuring 78 others, according to health ministry figures.

A few hours later in Alexandria, 17 civilians and police officers were killed as another suicide bomber blew himself up outside St. Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral, as the head of the church, Pope Tawadros II, lead the service inside.

“The pope is safe and was not harmed in the attack,” a short statement by Egypt’s interior ministry said later.

Responding in a short televised address on Sunday night, President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi said he will impose a state of emergency nationwide for a period of three months.