Robert Jackson Bennett's Blog, page 8

May 16, 2013

On outlining

I’m a bit in limbo at the moment, writing-wise – City of Stairs is off being judged and reviewed by any number of unseen eyes, and I’m just sort of sitting here, not wanting to jump into anything just yet because those judgments could be returned at any time.

However, after reading some interesting conversation over on Chuck Wendig’s twitter feed, I got a bit dragged into thinking about one of the thorniest writing questions out there:

To outline, or not to outline?

For those who don’t know, outlining is the process before a writer starts something when they essentially graph out everything that will happen in the book. It can be a summary, a chart, a timeline, however you want it, it’s basically an instruction kit for which part needs to go in which place at which time in order to Make The Book Go.

The benefits for outlining are several: for one, you know what happens. Each time you open up a blank page, you have a good idea of what should be on it. This is hugely valuable, and anyone who’s tried to write anything generally knows that.

For another, you will not forget necessary things. This is actually quite important: a book is a lot of moving parts, with plots surfacing during one point of the book and then submerging – still invisibly operating, unbeknownst to the reader – only to resurface at some incredibly crucial point down the line. There have been times when I’m rewriting something where I realize a character has received a piece of information from a source who has no business giving it; then I realize I had actually thought of a solution to this, and forgot to write it, which means I have to rewrite a lot more than I normally would have.

Which of course makes you ask – do I outline?

No. No, I don’t.

There are a couple of reasons for this. First of all being that, when I commit to a book, I usually do so knowing the start point and the end point. (I definitely know the end point – the start point often takes some readjusting.)

I know the image or feeling the book should end on; I know what I want the book to explore; I know the feeling and the ambiance and the color of the book; and so on, and so on, and so on…

So I have a very general trajectory. I know what I want to do. I just don’t quite know how I want to do it.

And that’s exactly what I want. I don’t want to know at all. The reason for this being that I am not actually in charge of anything I’m writing, or at least it feels that way. Books are their own things, their own identities, their own beings. Sometimes when I stumble on something that really, really works in a book, it doesn’t feel like I wrote it – it feels like it was always there, and I was just fortunate enough to unearth it.

I know it’s not always exactly quite like that, of course: books aren’t set in stone at the start. But they are organic: they grow and change and shape themselves. They know what they want to be, they have their own momentum, and my primary job is often just to get the hell out of the way.

More to the point, when a book or a character surprises me, that’s when I know it’s really going well. When something surprises the author, then it probably surprises the reader, and that’s good. Anything that throws off the audience but keeps them on the hook is a very, very good thing: the phrase, “That was exactly what I expected,” is not a positive thing to hear after someone reads your book.

A story must have room to breathe, and room to grow, I think. If I didn’t have that when I was writing, it’d take a lot of fun out of it.

But the question lurking in all this is… since you don’t outline, can’t that cause logistical problems?

And the answer is: oh my goodness gracious, yes.

I’ve had times in a book where a character didn’t really become themselves until the final third. I realize then, at that point in writing it, that they should have been this person from the start, so I have to go back and rewrite all their scenes to make them that person. This is actually extremely normal for me – it’s almost my default mode of writing characters. Find out who they are when it really matters, then go back and make them that person when it matters just a little bit less.

And there have been times when I’m writing a book when I think the book is looking at one thing, but towards the end I realize it isn’t, and I have to go back and adjust the path of the entire book until it rolls along and comes to the point where it examines the thing it’s supposed to. (This is less normal – knowing this is what makes me want to write the book. But it has happened.)

Are these really problems? I don’t think so. There are a lot of philosophies about writing, but one I subscribe to most is: writing is rewriting. Hindsight has 20/20 vision, and that’s even truer when it comes to writing. I rarely know what a book really, really is (or was supposed to be, I suppose) until I’m almost done with it. That’s when I have to go back and even it out, provide supports, make sure it’s paced properly – in other words, to use a coder term, to see if it properly compiles.

And I have tried outlining before (to a very loose degree), and in each case it didn’t turn out well. I had a fixed, outlined ending for characters in two different books, but when I was actually writing that book and writing their story, I could feel those endings changing, nudging me to different places… Yet because It Was Outlined, I felt obliged to keep it that way, and I violated their momentum by forcing their arc.

I didn’t keep the final stories in either case. I wound up having to rewrite them all anyway.

So my feeling is… since I usually have to rewrite outlined stories anyway, wouldn’t it be better to not outline at all, and give them the space to breathe and grow and become, well, more of themselves, as the saying goes?

May 15, 2013

I haven’t posted in a while…

…so here’s a dramatic rendering I made of two 5 pound dogs fighting for control of a welcome mat.

You’re welcome.

April 17, 2013

Oh yeah.

I was traveling Monday, and Tuesday was devoted to fixing all the stuff I didn’t do Monday, so it’s only today that I get to post that over at the Guardian, Damien Walters has mentioned me as one of the best 20 SFF authors under 40.

It is a little amusing that I’m primarily cited for Mr. Shivers, the book I wrote when I was 22, which seems so long ago and so absurd that someone thought a 22 year old could do anything of worth that it practically makes my brain hurt.

Old novels are like old photographs to their authors: you recognize that this was you, once, but it seems so alien that you used to be this thing that you can hardly understand it. You primarily see your failures and regrets, the things you didn’t know that you know now: for real life, you see how to talk to the opposite sex, how to behave professionally, how to do laundry, etc.; for writers, you see how this sentence was clunky, this idea was poorly articulated, all this here should have been cut, etc. I know I’m not alone in thinking this: I’ve heard of other authors revisiting their mega-hit works 10 years later with a distinct sense of unease.

I very, very rarely reread anything I’ve written once it’s in its final form. I certainly don’t want to reread Mr. Shivers or any of the rest anytime soon, chiefly because I’m afraid I’ll see all the things I know I can do better now. (I flipped through Mr. S a few times, and I could definitely tell a 22 year old wrote it – but this might be more in my head than it is in the text.) But this is part of doing anything, in that you must make mistakes in order to learn how to do better, and just because you made a mistake in a work, and learned from it, doesn’t necessarily mean that the work is bad. It just means you know more now.

And as a note, I am the sort of person who tends to believe that the thing he’s currently working on is The Best Thing Ever, and everything he’s ever done before was Obviously Just a Warm Up for The Best Thing Ever. Then, when I finish The Best Thing Ever, it immediately becomes another Warm Up. So I guess I’m saying I’m a pretty shitty judge of these things.

“How one writes,” or, “Why you should not marry a writer”

It’s an interesting idea, to me. Writing is a highly individualistic process – it’s one of the few jobs you can do entirely alone, inside your head. (Getting it published and read, however, is a huge team effort.) And it’s an extraordinarily complicated process as well, brimming with conscious and subconscious associations, connections, ambiances, tones, many abstracts that one can hardly articulate – an odd quality for a process that is, in essence, articulation.

I will say this: the actual articulation portion, for me, and I think for many writers, occurs when I’m faced with a blank page. When I say “articulation,” I mean the actual putting words behind one another, finding a way to make the events and people in my head manifest on the page. This is the actual work of writing, and – for me – it’s not unlike a salesperson who’s gone out and made a lot of deals having to come back to the office and log all those deals in the company database.

This is probably a hugely reductive metaphor, one that does a disservice to the actual manufacture of prose. A lot of incredibly important gears engage when you sit down and start to parse out sentences – and that’s the only time they engage. But in some ways the metaphor is correct, because the punching of keys and arrangement of prose is not the whole of writing.

For me, writing occurs almost as much off the page as it does on. Writing is a thing I never stop doing: some portion of my brain, in some respect, is always writing. Sometimes it’s a very negligible percentage – 1%, maybe 2% – and sometimes it’s very, very large, 80% or 90%. But there’s a lot of middle ground, when I’m mowing or folding laundry or driving or waiting to fall asleep when my brain is writing at about a 30% to 40% capacity, when I am pushing big blocks of ideas around and seeing what fits where. (My wife notes that there are times when she’s telling me something important, and I’m not meeting her eyes but my lips are moving like I’m whispering – and that’s when I’m probably figuring out a piece of dialogue in my brain. Before you ask, yes, she absolutely hates this. Don’t ever ask me to get something from the store – I am wildly unreliable.)

I get a lot of work done this way. I come up with an idea, take out my phone, and shoot myself an email that’s sometimes just a snippet of dialogue or an order myself to cut this or add that. My gmail is currently at 60% capacity, using 6.1 GB of my 10.1 GB, and I’d guess that a good 10% to 15% of that are emails from myself to myself – they don’t have huge memory requirements, because they’re just 5 to 10 words, but there’s so many that I’m sure they make a dent.

But I’m not always writing the book I’m currently concerned with: there are a lot of pet projects I mentally compose, usually something akin to fan fiction or movie scripts. Many times when I fold laundry I’m mentally preparing myself for the time when everyone forgets about the M. Night Shamylan movies and I can have a go at writing the Avatar: the Last Airbender movie scripts myself. Or, I’m dreaming of the day when I get a deal from FX and can make a serialized Batman cartoon myself, a slightly more grown up version of The Animated Adventures, a show that’s zippy and fun but has all the complicated institutional interplay of something like The Wire.

This isn’t probably productive work, but it’s hugely necessary nonetheless: writing is a mental state you have to be able to slip into and slip out of easily. It’s something you need to learn how to activate and catalyze as much as you can. It’s both a muscle and a meditative state, a part of yourself you need to go to whenever you’re able. So even if what you’re writing isn’t something you plan to sit down and, well, write, it’s still important to mentally flesh things out, develop a feel for what’s working and what isn’t, and…

Well. You never know. Those good scenes in the silly little projects you dream up might wind up working exceptionally well in a big, important project much later.

April 12, 2013

i09 review, and the AMA

Well, my Reddit Ask Me Anything was completely fucking nuts. But I never expected it to be anything different.

American Elsewhere has also netted a very nice review from i09, as well!

The book is science fiction, but has at least a splash of horror, unsurprising for a novel by a Shirley Jackson Award winner. Horror is a deeply subjective genre – second only to erotica – and I’m not particularly put out by tentacular grotesques or things that go chitter in the night. Or rabbits. Those who find their nightmares haunted by the chitinous or oozing, may find the horror more pronounced. But in any case, these things are pressed up against more suburban horrors: the desperate need to keep up appearances, a stifling marriage, parents who sacrifice their children for the protection of a powerful patron. It’s the combination of the two, the mundane and the Lovecraftian that give the book an unease that seems to radiate from the pages.

I’ll be checking on the AMA occasionally throughout the day, so if you have a question you’d like to ask, please feel free to do so!

April 11, 2013

Reddit AMA

I’ll be doing a Reddit Ask Me Anything today. You can post all the questions you have for me there, and I’ll be returning at 7 PM CST to answer them.

April 10, 2013

On masculinity

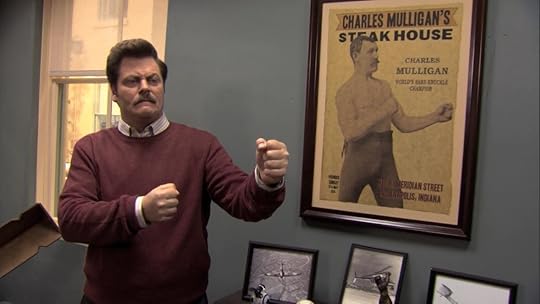

Probably one of the most feverishly adored characters on television right now – among a certain demographic of viewers, including myself – is Ron Fucking Swanson.

Probably one of the most feverishly adored characters on television right now – among a certain demographic of viewers, including myself – is Ron Fucking Swanson.

Why? Because Ron Swanson is old school masculinity to the point of deconstruction. He’s uber-competent. He’s indifferent, and supremely dismissive. He’s self-reliant, and confident. He’s contemptuous of anything emotional or modern. He doesn’t need anything, and he’s definitely not going to ask you for anything. He’s a walking, talking anachronism, an early 20th Century Man (or even 19th Century) living in the 21st Century – without, you know, the racism, sexism, and so on.

A lot of this character’s appeal comes from the brilliant work of Nick Offerman, the actor who plays him. Offerman underplays Swanson to an unbelievable degree, usually donning a dead-eyes scowl and murmuring his lines with a Midwestern nasal growl. And a lot of Swanson is based on Offerman, a Midwesterner, carpenter, and respectful manly man.

A lot of the love for Swanson dovetails with a broader trend for the ornaments of old-school American masculinity: beards, mustaches, pipes, pomade-slick hair, and a lot of dark wood, 19th century interior designs are currently the hippest of hip. This has led some to speculate on the state of masculinity in America: do the progressive, hip men of today adore the men of bygone eras because they know their own testosterone isn’t up to snuff?

To which I respond: eh.

The historical aspect

As Ron Swanson is, in a lot of ways, an amalgam of masculine archetypes from anywhere from the 1890’s to the 1950’s, it’s worth examining those actual historical eras, and what was happening. This nostalgic perception of masculinity didn’t come from nowhere, after all.

In a few broad strokes, from the 30′s to the 60′s, you had around two whole generations of men who had been in overseas combat and had gone to school on the GI Bill. This was probably the largest civic mobilization of a demographic in American history: not only training generations of men to be highly resourceful, self-reliant servants (while also learning to operate within a system – for what bigger system is there than the American military?), but also actually, genuinely teaching them, sending them to school to learn things they never got the chance to before.

And that’s probably a huge factor: the men Ron Swanson seems to reference were likely the very first people in their family’s history to achieve this level of education and success. These people were given incredible opportunities (under incredibly hardships, of course) at a time when America was firing on all cylinders. I sincerely doubt if any large demographic is or could be placed in such a sweet position today.

In addition, it’s worth noting that these opportunities in those eras were only offered to a select few. Women did not get any of those opportunities, so that’s half the population right there that’s not competing. Minority males may have gotten some degree of these opportunities, but I’m willing to bet that whatever they got was a much-reduced package in comparison to what white males received. So you had one specific demographic that essentially got handed the keys to what was, at the time, a brand-new, incredibly nice car, and everyone else got to watch them drive it away.

But things go beyond the historical perspective. Not only do we not have the opportunities that created men who were, to an extent, like Ron Swanson – we also don’t have much need for one of their greatest virtues.

We don’t do that anymore

The appeal of Ron Swanson (and the fundamental appeal of general masculinity, I think) is the concept of resourcefulness. Ron Swanson doesn’t buy a house: he goes out in the woods, chops down 30 trees, and builds one. He doesn’t get his car serviced: he fixes it himself, and if he needs a part he smelts one in his own goddamn smithy.

Not only do I think that, on the whole, that’s not what we’re training or preparing coming generations to be, but I also think that way of life is more or less defunct. We’ve developed our economy and our culture in a manner that it’s easier to buy a new shirt than it is to fix your old one. If your kitchen appliance breaks down, we are not trained to take it apart and fix it – we just go to Target and get a new one. We’re slowly entering a stage of post-scarcity, where we have an abundance of goods, and a better use of your time is not to fix or repair the cheap thing you have, but to get a new one – something the people in the 30′s, 40′s, and 50′s probably thought was unimaginable.

This also extends to cars and computers. Apple specifically makes it so you can’t take Powerbooks apart and noodle with them: they want you coming back to the store. Cars these days are more computers than machinery, and I dread the idea of trying to do work on my Prius. (Cue my wife laughing immensely.)

This isn’t to say that this is a good or a bad thing – it is what it is. This is the world that we’ve chosen. We’ve opted to maximize individual buying power over individual resourcefulness. Ideally, this means we spend less time on the day-to-day minutiae of living – mending clothes, fixing cars, fixing your house – and more time on greater abstracts previous generations didn’t have the time for. (Reality television, pornography, etc.)

We’ve made a trade, in other words, but I think we’re discovering that we valued the pride derived from that resourcefulness more than we thought.

However, it is worth noting that this new economy, driven by extreme quantity, is possibly a creation of another 20th Century masculine archetype.

So what’s a man to do these days?

I think it’s time for a reconceptualization of what we think it is to be a man.

I was thinking of my own ideas about masculinity, which change the older I get. I’m not a kid anymore. I have a wife, a son, and I essentially work two to three jobs. I don’t spend three hours a day at the gym like I used to. I don’t drink beer all the time and I don’t rotate through a series of women. And I don’t especially know a huge amount about home repair or fixing up my car. (Landscaping is another matter, though.)

So what I do I, personally, think of as masculine? Well, I was casting around for an icon manliness that would work in the 21st Century – or indeed any century – and what I came upon was a little less Ron Swanson, and a little more…

Aah, yes. That’s a lot more like it.

The more I think about it, my ideal perception of masculinity has a lot less to do with the material world – what you can do with your hands and your body – and a lot more to do with the moral, abstract one.

So I made a list of qualities I think of as masculine, ones that I feel have a lot more applicability these days.

1. A consciousness of others

A real man puts others ahead of himself. He thinks about what those around him need, about what his community needs, about the larger picture beyond just himself, what he wants, and his own goals. He thinks not only about other people, but about what other people think and how they think it, and he’s willing to change his viewpoint and be persuaded based on these considerations.

2. A devotion to supporting and providing for the family

Here’s what I define as a family: a close-knit group of people that learns from you, while also teaching you plenty of things. Blood or familial relation is not a necessity, at all. And I do think, increasingly, that a willingness to share your life with others is a much better good than complete and utter independence and detachment. And I personally identify a willingness to work, support, teach, and learn from the people you’ve shared your life with as a very masculine quality.

3. A willingness to reconsider and compromise

I think a real man prioritizes, figures out which good things are most important, and is willing to put lesser good things on the line in order to have the best impact for the most amount of people. The ability to be reasoned with and persuaded seems to be a rare thing these days; in fact, the very opposite appears to be considered a masculine quality now: the most stridently belligerent and bull-headed people are usually considered manly men.

And that’s really it. These are the three things I identify as the Atticus Finch Brand of Masculinity.

But once I thought about this, I realized something.

What I’m laying out here isn’t masculinity: these are basic moral tenets. If you reread the three qualities I laid out here, and replace “a real man” with “a good person” and “masculine” with “moral,” then this whole thing still makes perfect sense.

Anyone can have any of these qualities and still be considered whatever the hell you want to be considered as – they’re functionally genderless.

Being a good person is manly. Being a good person is feminine. Being a basically decent person should be, in other words, the centerpiece of any sort of ideal human being, regardless of gender, creed, or nationality – and doing so does not detract from that ideal, only add to it.

April 8, 2013

52 Book Reviews, uh, review

A very nice review of The Troupe is up at 52 Book Reviews:

[...]Bennett has produced a novel that defies easy description, blending elements from genre and story into a rare hybrid that can appeal to all lovers of well crafted tales. When I recommend this book in the future, as I know I will, I will take an approach I save for only the most prized books on my shelves. I’ll simply ask; do you like to read?

Always very nice to hear.

April 3, 2013

Some thoughts about awards

I still consider myself a literary award newbie. This is weird to say after 4 years of doing this, but it’s true, mostly because there are so many awards, each with their own cultures, each saying something different about some aspect of the genre. It’s tough to know them all.

I still consider myself a literary award newbie. This is weird to say after 4 years of doing this, but it’s true, mostly because there are so many awards, each with their own cultures, each saying something different about some aspect of the genre. It’s tough to know them all.

The biggest award in SFF is, with little debate, the Hugo Awards, the nominations for which just got announced this past week. When I first got started being a writer, I knew very little about the Hugos, beyond that Ender’s Game had won it (because it had a big shiny silver star saying so on the cover of the copy I stole from my brother – it also had one for the Nebula, another big award I knew very little about when I first started writing).

The Hugo, like any award, has its own very distinct culture, and also like any award, every time the nominations come out, there’s a flurry of discussion over what does it mean? As if the nominations are an alien language, and we are trying to figure out their message.

However, I’m not sure this is necessary, because there are only about three different kinds of industry awards, and each kind tends to articulate and message three very different things.

Every industry award, when you get right down to it, is a statement of What Is Best of that industry. What makes each award different is which body is deciding What Is Best, and there are really only three possibilities:

The industry itself

The users of that industry

A small group of elites, preferably independent of the industry

In the case of #1, this is the industry itself deciding what is best about itself. The best example would be the Oscars, given by the Academy, IE, the movers and shakers in Hollywood:in this case, these are not only the established elites, these are the manufacturers of the product being judged.

In the case of #1, this is the industry itself deciding what is best about itself. The best example would be the Oscars, given by the Academy, IE, the movers and shakers in Hollywood:in this case, these are not only the established elites, these are the manufacturers of the product being judged.

Naturally, there’s a danger of conflict of interest, and this is usually the criticism leveled against Hollywood by those disenchanted by the Oscars: that they do not decide What Is Best as much as advertise the movie industry, and say things about the movie industry that the industry itself wants everyone to hear.

I suppose if there’s any SFF award that falls into the #1 category, it’d be the Nebulas, but it’d really be any award given by a professional association of writers that gives its dues-paying membership the right to nominate. I doubt if any SFF award receives as much criticism as the Oscars (I am not hugely knowledgeable about this sort of insider gossip), but if the manufacturers of a product decide - on a large scale, mind – which product manufactured Is Best, then the award they give is automatically a category 1.

Overall, the real issue of a category 1 award is not self-promotion (that’s usually pretty transparent, and tends to eat itself or balance itself out), but messaging with an agenda: the award could be a statement about the industry rather than a statement about what is awarded. For example, if the Automobile Manufacturer’s Association flew in the face of the push for sustainability, and nominated all cars with exorbitant gas consumption, that would not be so much a legitimate recognition of What Is Best as much as a “fuck you” to the sustainability movement. (I hear complaints in sports that the Coaches’ AP poll does a lot of this – making a broad statement with votes.) In literature, I expect it’s very easy to do something like this, to make a cultural statement of What Is Best rather than a specific creation being Best.

For category 2, the users of the industry, what they are deciding is what is most liked out of what is most used. If an industry product is not well-used, it almost certainly will not be nominated. This is more or less what the Hugo is, though there’s a filter in that you have to pay a fee in order to get to nominate and vote. This changes the culture of an award – it’s either people who really like what they’re nominating, or they’re regular convention-goers – but it doesn’t change its nature.

For category 2, the users of the industry, what they are deciding is what is most liked out of what is most used. If an industry product is not well-used, it almost certainly will not be nominated. This is more or less what the Hugo is, though there’s a filter in that you have to pay a fee in order to get to nominate and vote. This changes the culture of an award – it’s either people who really like what they’re nominating, or they’re regular convention-goers – but it doesn’t change its nature.

Ideally, the voters of the Hugo encompass all three groups – industry, users, and critics – but it’s pretty clear that it’s the users who are determining the majority of the nominations and votes. (Of course, in our abstract field, one could be all three things – more on that later.)

As the Hugos follow this award model, this means that they’re less like the Oscars than they are any other popular pop culture vote. I initially would say the touchstone reference would be American Idol, but that’s not the case because there it’s a large group of unknowns being judged. For the Hugos, it’s usually a small group of either fairly successful or astronomically successful authors being judged, simply because this award model decides, as I said, what is most liked out of what is most used.

The immediate thing that comes to mind are the various Choice Awards out there – Viewers Choice Awards, People’s Choice Awards, Teen Choice Awards, etc, things that take a set of highly visible entertainers and artists (sometimes through an online nomination process) and essentially poll the audience. This is similar to what the Hugo does, though, as I said, the Hugos apply a financial filter that affects the voting bloc.

Category 3 is probably everyone’s least favorite process, because it limits the participation to the greatest extent. This would be a jury of (ideally) independent, objective, established critics who look at a broad range of submissions and decide What Is Best based on their own personal inclinations and discussions.

Category 3 is probably everyone’s least favorite process, because it limits the participation to the greatest extent. This would be a jury of (ideally) independent, objective, established critics who look at a broad range of submissions and decide What Is Best based on their own personal inclinations and discussions.

This is the Wild Card process, the one where you put the power in the hands of a few and they could very possibly go hog wild with it. (Or, like the Pulitzer for Fiction in 2012, not award anything at all, as a way of saying everything sucks.) These people could be susceptible to industry insiderism – as critics, they doubtlessly know producers inside the industry that they are judging. They could even be industry producers themselves, judging other industry producers. However, they would be judging their colleagues as an individual, rather than a system of colleagues judging itself, which means they’re easier to check.

But it’s possible to enforce objectivism in creative ways. In architecture awards, it’s common for the jury to consist of architects originating far, far away from the area they’re judging: if it’s a California competition, the jury could be from Germany, China, etc. This means they probably have very little ties to California, so there would be no conflict of interest.

However, since these awards ideally pay no attention to popularity, their selections are often criticized for being too obscure, too random, or too strange: because the critics have a barrier between themselves and the industry, they are not forced to yield to any of the industry’s expectations. Indeed, critics are often admired for being explorers of their field, and finding things that people did not know about: but since awards are often entertainment-oriented (either by profession, or because the handing out of the awards is pretty damn entertaining), people want to see the things they know get recognized.

The real question about category 3 is – who decides who gets to sit on the jury, and why? Who decides the criteria of the award? And that’s when you have to start the What Is Best question all over again.

So which system of deciding What Is Best is actually, well, best?

That depends on what you want to see. Do you want to examine the whole of the industry, including the obscurities, and look for singular artistic accomplishment along a specific criteria? If so, then your odds of accomplishing that are:

Category 1: kind of high

Category 2: very low

Category 3: very high

Do you want your awards to have high participation, to be a lot of fun, to generate a lot of talk, and create a list that is, in essence, What’s Hot? In that case, your odds of accomplishing that are:

Category 1: kind of high

Category 2: very high

Category 3: very low

Do you want to further your industry, to change people’s minds about your field, to advertise what you’re doing and grow your business? If so, your odds of accomplishing that are:

Category 1: very high

Category 2: kind of high

Category 3: very low

Of course, in literature, there’s not only the conflict of interest, there’s the ease of occupation: as workers in an abstract medium, it’s really easy to be a producer, a critic, and user of an industry. I write, read, and critique all the time. So it’s even harder for literature, where the occupational differences are less clear – though I do think the overall function of the models will remain the same.

How do I feel personally about the Hugos?

I feel about the Hugos about the same as I would about an automobile association award, or an architecture award: I don’t think it has a whole lot to do with me. I usually find that I only read any of the nominees about one out of the every three years, just because of my reading inclinations. (I haven’t read any of the nominees this year, or even the ones people wanted to see nominated.) And probably because my reading inclinations affect my writing inclinations, I don’t think my stuff is particularly Hugo-worthy material. The Hugos have broad, unspoken criteria – again, there’s the culture-thing – for what they’re looking for, and my stuff is just not that thing.

And that’s okay – I’m not upset over that any more than the fact that I didn’t get nominated for an Orange Prize: I’m just not writing that stuff. (Also I’m a dude, so.) I don’t have any plans to write specifically Hugo stuff, either – I like to think that, even though I’m now “in the industry,” I’m still writing the books I’d like to have written when I was first starting out, completely ignorant of everything.

(And as a note, I’m aware – to a very great and personal extent – than neither an award nomination nor an award win is a great guarantee of sales. However, if you’re nominated for a Hugo, I do find it hard to imagine that this could happen without a fairly successful sales rate – most people do not vote for things they do not know, and the way one knows a book is by reading it. If your book is there, it’s essentially one of the more successful five SFF books of the year – something a lot of authors would dream of getting.)

But it’s always fun to talk about two pet themes of mine: determining the nature of big systems, and systems of determining What Is Best.

March 26, 2013

Sci-Fi Bulletin Interview

An interview with me is now up at the Sci-Fi Bulletin. Easily the most important answer I give is this:

I suppose I would like to be asked which type of tree is the best to sit under at 6:00 PM in the evening. (A live oak.)