Phyllis Edgerly Ring's Blog, page 41

May 12, 2014

To live while we’re alive

Gleanings found here and there:

“Treehugger”, Tobey A. Ring

It is not the end of the physical body that should worry us. Rather, our concern must be to live while we’re alive – to release our inner selves from the spiritual death that comes with living behind a facade designed to conform to external definitions of who and what we are.

~ Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

We have been called to heal wounds, to unite what has fallen apart, and to bring home any who have lost their way.

~ St. Francis to the first friars

Blossoms, Vanessa R. Jette

“As long as this exists,” I thought, “and I may live to see it, this sunshine, the cloudless skies, while this lasts, I cannot be unhappy.”

The best remedy for those who are afraid, lonely or unhappy is to go outside, somewhere where they can be quite alone with the heavens, nature, and God. Because only then does one feel that all is as it should be and that God wishes to see people happy, amidst the simple beauty of nature.

As long as this exists, and it certainly always will, I know that then there will always be comfort for every sorrow, whatever the circumstances may be. And I firmly believe that nature brings solace in all troubles.

~ Anne Frank

May 10, 2014

A first teacher’s gifts

Remembering Peggy Wilson Edgerly

Remembering Peggy Wilson Edgerly

My mother didn’t have a “real” birthday except during leap years, which means that when her death certificate recorded her age as 80, she was still technically only 21.

In the months before the sudden heart attack that ended her earthly life, there were beginning to be discernible signs of age, such as the slight bend in her slender frame. But the challenge her grey-blue eyes tossed back at the world, even then, always made her seem like a feisty young adult. And whatever her age, she was always an initiator of welcoming hospitality and reaching out to others.

Mothers truly are our first teachers, which may explain why we can feel so inexplicably alone once they’re gone. With each passing year, so much of what I value can be traced back to my mother, a military spouse whose life didn’t turn out anything like her 21-year-old self imagined it would.

Buttermere Lake, photo: Kathy Gilman

During the years my dad was at war, my young British war-bride mother held down the fort in her family’s home not far from England’s Lake District. She cared for my newborn older sister, along with an elderly relative in the last stages of cancer, plus several children who’d been evacuated from London. Somehow, she also found time to hook rugs to generate income to compensate for the meager wartime rations on which her crowded household had to subsist.

Having been a young mother myself, I now wonder how she ever found the time to do these things — that she took in those young evacuees at all. She knew, however, what kind of life they’d face back home in the city during wartime, because her young face already wore nasty scars from her service as a fire warden during the infamous “Blitzkrieg.”

If anyone modeled for me how to welcome change gracefully, it was my mother, who came to a new culture to meet her Boston-Irish in-laws, then proceeded to make a home for her family — over and over — in locations all over the world. Her dedicated “nesting” efforts gave every place we lived that consistent feeling of home, however often we were uprooted and forced to start over.

Photo: Lara Kearns

Life in a military family meant I had to keep making new friends, and my mother, as with most everything, encouraged me in this endeavor and did her best to turn it into an adventure. She made it easier to nurture friendships by always welcoming playmates at our house and utterly charming them with her warmth. (They usually loved her accent, too.) Friends still talk about how inviting it was at our house, while I grew up believing that’s how it was everywhere.

Because she was such a canny yet unobtrusive ally in assisting our friendships, my sister and I now find it easy to make friends wherever we go, to be the one to go talk to someone standing alone at a party, as we often saw her do. With her lively mind, she always had friendly, interesting questions that would gently coax people into the nicest conversations, even if she had to ask them in a language she was struggling to learn.

Long before the days of what the sixties would label Women’s Lib, military spouses like her were already demonstrating women’s versatility and capability, strong models for their daughters — and sons. When you’re so often the only parent on the scene, there’s simply no room for the kind of thinking that’s limited by gender bias.

Photo: http://www.etsy.com/shop/DKirkupDesigns

Among other invaluable gifts, she was able to listen in a way that made you feel that hearing you was the most important thing in the world. She also taught me how to value and use my own time — not just to be efficient and accomplish things, important as that is, but to also savor and enjoy something worth enjoying.

It makes me more than a little sad that I recognize these things now that she isn’t here to thank in person. “A father and mother endure the greatest troubles and hardships for their children; and often when the children have reached the age of maturity, the parents pass on to the other world,” the Bahá’í writings acknowledge. “Rarely does it happen that a father and mother in this world see the reward of the care and trouble they have undergone for their children. Therefore, children, in return for this care and trouble, must show forth charity and beneficence, and must implore pardon and forgiveness for their parents.”

After my mother’s death, the one thing I heard most consistently from the many who loved her was how much kindness she’d always shown them. Thus, it’s quite clear how I can best honor her memory. Her modeling of kindness and generosity is likely the most important lesson my first teacher ever gave me.

So, thanks for everything, Mum. You’ll always be twenty-one to me.

Adapted from Life at First Sight: Finding the Divine in the Details.

May 7, 2014

The allies of soul-making

“Summer Tree”, Laura Moore Watercolours.

So many thoughtful souls keep us company when we’re on a path of creating.

“Creativity arises out of the tension between spontaneity and limitations, the latter (like the river banks) forcing the spontaneity into the various forms which are essential to the work of art or poem,” said Rollo May.

Kurt Vonnegut said, “The practice of art isn’t to make a living. It’s to make your soul grow.”

“People don’t talk about the soul very much anymore,” Anna Quindlen has noted. “It’s so much easier to write a résumé than to craft a spirit.”

“Papaveri”, Laura Moore Watercolours.

“Weaving, writing and painting our stories into the things we create is a way of feeding the Holy in Nature, which has kept us fed and alive,” says Toko-pa. “And as we put all of our lostness and longing into the beauty we make, we do so knowing that we may never hope for more than to pass on these heirlooms to the young ones so they may find their way home across the songlines, as we have been found by those who made beautiful things before us. If even one generation is denied their inheritance, the story and the way home may be lost. As it is said in West Africa, ‘When an elder dies, a library burns to the ground’.”

And finally, this beautiful encouragement from Craig Paterson: “Whatever difficulty you may be working through today, find a point of solace in art. Let it be both comfort and crucible, to rest your weary heart and to transform the dense dark matter of your troubles into something new and clear. Make beauty and vulnerability your allies in your brave journey of becoming.”

May 3, 2014

Life has not forgotten us

Photo: D. Kirkup Designs

Gleanings found here and there:

… remember that life has not forgotten you; it holds you in its hand and will not let you fall. Why would you want to exclude from your life any uneasiness, any pain, any depression, since you don’t know what work they are accomplishing within you? ~ Rainer Maria Rilke

Image: D. Kirkup Designs

Doubt is a pain too lonely to know that faith is his twin brother.

~ Kahlil Gibran

Oh, these vast, calm measureless mountain days, inciting at once to work and rest! Days in whose light everything seems equally divine, opening a thousand windows to show us God.

~

John Muir

Suffering is the Mind’s response to sadness or pain. If you suffer while experiencing sadness or pain, you have clearly made a decision that you should not now be experiencing it. It is this decision, not the sadness or pain itself, that is the cause of your suffering. …

Suffering is your announcement that you may not fully understand why it is arising, and how it all fits into the Agenda of the Soul. When you fully comprehend exactly what is taking place in your life, as well as the Process of Life Itself, then your suffering ends, even if the pain continues. Nothing changes, but everything is different. ~ Neale Donald Walsch

Find more work from artist Diane Kirkup at: http://www.etsy.com/shop/DKirkupDesigns

April 30, 2014

Life at the speed of two languages

I am living and reading in two languages. Sort of.

I am living and reading in two languages. Sort of.

I’m in Germany for, among other things, work on a book, which I do in English. (Or at least, I like to think so.) Meanwhile, the rhythm of the rest of my life right now is mostly a German soundtrack.

I know that the more time I spend writing in English, the more I flounder in German. Sometimes, when I’ve been really immersed (one might almost say relaxed into) German, I struggle for the words in English. At times, I feel like a refugee from the lands of both languages.

The remedy for this arrived on a recent rainy weekend when Buchhandlung Moritz & Lux was kind enough to have its Wertheim branch open. When I get to feeling a bit lost in the world, or a day, I can always find balance again in a bookstore.

This one eliminated my taking the easy road – there was no English section. I was nearly contenting myself with a book of Anthony de Mello’s, as he’s a longtime friend of my soul. But geesh, I knew it would be tough going.

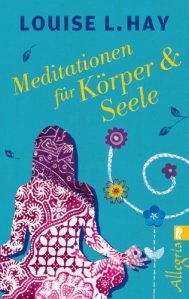

Then, there she was on a shelf next to his – old friend Louise Hay, God bless her. I could feel instantly how perfect this was. This is the kind of reading that, I knew from experience, I would do with my heart — which, I’m realizing, is the only way I ever really do anything. So if I want to deepen into German, this is the soul-sized way, for me.

Meditationen für Körper und Seele, it’s called – Meditations for Body and Soul. The blurb advises: “Mit diesen Meditationen erhalten wir den wichtigsten Schlüssel, um negative alte Gedankenmuster aufzulösen und wieder Vertrauen in die positiven Kräfte des Lebens zu gewinnen.” With these meditations we receive the most important key to resolve negative old thinking and restore confidence in the positive forces of life to win.

Or, one might say, we “restore confidence” (love that phrase) in the power of the building of the good. Isn’t life ever-delightful in the way it nudges toward the very next just-right thing?

April 26, 2014

Coming home by heart

I’m back in Wertheim, my old hometown, where I lived 50 years ago high on the hill above town in a place called Peden Barracks.

I’m back in Wertheim, my old hometown, where I lived 50 years ago high on the hill above town in a place called Peden Barracks.

Back then, the Cold War meant there were whole parts of Germany my family couldn’t travel to. Today, irony of ironies, the building I lived in is home to families who came to Germany about 20 years ago as refugees from parts of the former Soviet Union.

Each day, I listen for the church bells, or the latest train arriving at the nearby station. As this is my primary means of travel right now, I’m extra-aware of trains.

Each day, I listen for the church bells, or the latest train arriving at the nearby station. As this is my primary means of travel right now, I’m extra-aware of trains.

As I’m out and about in the marketplace, I can have a bit of a conversation with someone in German when I don’t over-think things. My German seems to work when I don’t think about it too much.

My writing days are assisted by fresh Brötchen with good butter and miles-long walks. The walks don’t feel miles-long because I’m exploring and looking at so many things, a kind of imbibing that’s even more enjoyable than each morning’s coffee and good Brötchen.

After a tasty dinner at the restaurant up at the castle the other night, things looked truly beautiful as I gazed out from on high. The church bells near the market square were tolling their 6 o’clock symphony and the moon was near the horizon.

I’d had another day of productive writing hours, which is why I let myself celebrate with that dinner. Each day begins with the sun’s light, and draws to its close with the moon rise, and my heart feels very thankful for this rhythm of life.

Each night, I “ask” — put my request for help down in writing in the novel’s journal.

Then, I wait to see what comes each day.

It’s a reassuring and reinvigorating process — good practice for the rest of life, too.

April 23, 2014

Coming to our spiritual senses

In this world we possess both outer and inner senses. The first helps us to navigate in the world, while our inner senses enable us to connect with our soul’s highest purpose and manifest it.

In this world we possess both outer and inner senses. The first helps us to navigate in the world, while our inner senses enable us to connect with our soul’s highest purpose and manifest it.

In the next world, the equivalent of our inner, spiritual senses are the attributes of God. Such divine qualities as love, justice, mercy, and patience become our eyes and ears, so to speak.

If we only developed the many facets of these attributes during what we define as our happy times in this life, we would be unable to fully discern the world beyond, because we would not have fully developed our spiritual senses enough to be aware of all that that reality includes.

The times that we characterize as difficult in this life are named so because they usually go against the grain of our desires. Yet those desires are often defined by our human nature, which bases its assessments on past experience. Even in this world, there is so much more that we can know, but it requires being willing to go beyond the perceived limits of our past experience.

One of the spiritual attributes of God, also a name of God, is the Creator. As with all attributes of God that we have been asked to acquire, this one has facets of both giving and receiving. Thus, a wide variety of experience — including the painful and difficult — offers the contrast that helps us build our capacities for both giving and receiving. This is indispensable if we are to fully develop any attribute, particularly the attribute of creativity.

Unless we adopt an unlimited belief in our ability to create, we will never know what we are capable of creating. Cultivating an unlimited faith in the rightness of every one of our experiences to bring exactly what’s needed for the very highest possibilities in our development and that of other souls is a wonderfully effective way of “coming to our spiritual senses”.

Photos courtesy Saffron Moser and Nelson Ashberger.

Photos courtesy Saffron Moser and Nelson Ashberger.

Co-authors Ron Tomanio, Diane Iverson, and Phyllis Ring explore related themes in With Thine Own Eyes: Why Imitate the Past When We Can Investigate Reality? from George Ronald Publisher.

Buy the book at: http://www.bahairesources.com/with-thine-own-eyes.html

or find the Kindle version here:

April 19, 2014

The season of hope and renewal

kind Photo: David Campbell / http://www.GBCTours.com

One German friend’s story gives a glimpse into how big, surprising – and kind – the human heart can be.

Toward the end of World War 2, on Good Friday, some of his ancestors were expecting their tiny village to be overrun at any moment by U.S. soldiers. The German troops were retreating, and my friend’s family members, six adults and two children, were trying to decide whether they should stay put or hide in hills above the village.

In a previous war, their village had been wiped out in a similar situation, with every single person killed, so they were quite fearful. They also had a family member who was a prisoner of war overseas, one with whom they would later be reunited, and who would become my friend’s father. All they wanted to do was to be able to live their simple life in terrible times, during a war they’d just as soon had never happened.

They decided to stay in their home, and within hours, several vehicles pulled into their farmyard and U.S. soldiers climbed out and ordered them upstairs while the soldiers took over the lower floor of the house. What my friend’s aunt, who was among those present, most remembers is how young these soldiers looked to her at the time. As she and her sister peeked down from upstairs, she saw that the soldiers were having trouble figuring out how to light the cook stove, and so, to her family’s horror, she bounded down to help them. (Her sister would later tease her that the only reason she’d done this was because those soldiers were so handsome.)

They decided to stay in their home, and within hours, several vehicles pulled into their farmyard and U.S. soldiers climbed out and ordered them upstairs while the soldiers took over the lower floor of the house. What my friend’s aunt, who was among those present, most remembers is how young these soldiers looked to her at the time. As she and her sister peeked down from upstairs, she saw that the soldiers were having trouble figuring out how to light the cook stove, and so, to her family’s horror, she bounded down to help them. (Her sister would later tease her that the only reason she’d done this was because those soldiers were so handsome.)

That weekend, they all eventually feasted together on the farm’s fresh eggs and the soldiers’ rations in a shared meal around that kitchen table. On Easter Sunday morning, the family came downstairs to find the soldiers gone, along with a basket of hard-boiled eggs that the family had colored earlier that week. In the basket’s place was a huge stash of chocolate.

Photo: David Campbell / http://www.GBCTours.com

“My family hadn’t seen chocolate for years,” my friend says, “and this, combined with how carefully the soldiers had left everything in its place when my family had expected them to ransack the house, gave everyone great heart, and the possibility of believing that maybe things would be all right after all.”

The miracle of his father’s return a short while later was the very best evidence of that, of course, and soon spring bulbs were blooming in the yard and, despite the ravages of the war, his family knew that they’d see green fields again.

Photo: Saffron Moser

It’s no coincidence that the essence of Easter – resurrection — is about restoration and renewal.

Whatever our faith, or lack of it, spring brings that glorious reminder that, no matter what has happened, no matter how long our personal winters may have been, the spiritual pulse of springtime always offers us a new beginning.

April 16, 2014

Too precious for anything but gratitude and joy

I’ve been retracing a path of family history, following portions of the route that brought my parents together in England during World War II and eventually resulted in my speaking German (well, a kindergartner’s “German”) almost as early as I spoke my mother tongue.

During the U.S. occupation of Europe after the war, my military family spent two tours in Germany, the last of which holds my oldest memories. In the winter of 1960, we sailed across the Atlantic to a very new life. As military housing was at a premium, we lived “on the economy,” first in a hotel that I still visit, then in a tiny village 45 minutes from Frankfurt. A family named Geis welcomed us into the ground floor of their home while they squeezed upstairs to make room for us.

Photo: D. Kirkup Designs

Contrary to popular belief about German-American relations at the time, they were unfailingly kind and astonishingly generous, especially since they had very little after the war. While they no doubt welcomed the money they received for sharing that clean, accommodating space with us, they always felt more like grandparents than landlords to me.

What I remember most is how cheerful and happy they always were. I later learned that Herr Geis, like my family, was a recent arrival in Germany. Before that, his wife and children had waited 15 long years while he was a prisoner of war in a Russian prison camp, wondering whether they’d ever see him again. I understand now that after he came home, they saw every day as a new beginning and treated it like something too precious to waste on anything but gratitude and joy.

It was during Easter week that this couple and I shared one of my earliest intercultural exchanges. One day my parents had some appointments and errands and the Geises offered to watch me while they were away. My four-year-old self delighted in the day’s pursuits, which actually involved little more than following along behind the couple as they did their chores, preparing the field behind their home for planting, and helping me discover some stray potatoes they’d missed at harvest time.

It was during Easter week that this couple and I shared one of my earliest intercultural exchanges. One day my parents had some appointments and errands and the Geises offered to watch me while they were away. My four-year-old self delighted in the day’s pursuits, which actually involved little more than following along behind the couple as they did their chores, preparing the field behind their home for planting, and helping me discover some stray potatoes they’d missed at harvest time.

After we’d eaten those at the mid-day meal, together with eggs we’d collected from their hens, they introduced me to my first Easter eggs.

We were coloring them when my parents appeared at their kitchen door, bearing some traditional American fare — Hershey bars and a big bowl of popcorn — that they’d brought as an Easter gift and thank-you.

Most Germans had never seen popcorn, since corn was grown only for animal feed in Europe in those days. That bowl lasted for hours as the Geises removed a piece at a time, holding it up and marveling as they named the creature or object that its shape approximated. Eventually, we all began to do the same amid lots of laughter, and a pretty good vocabulary lesson on both sides of our collective language barrier.

This event stands out in my memory because it signals such a perceptible shift in my family’s bond with the Geises, the kind that meant they’d become regular guests at our military-base quarters on-base quarters long after we’d moved from our temporary shelter in their house.

I didn’t know of any other American families who shared this kind of friendship, and after my mother’s horrific experiences during the Blitz in Britain, most anyone would have forgiven her if she’d been hesitant to embrace Germans.

As I travel through Germany on Easter all these decades later, I feel eternally thankful for parents who were always able to see the humanity in any situation, above and beyond past history or politics. I realize today what a vital part of peace-building this is.

Adapted from Life at First Sight: Finding the Divine in the Details –

April 13, 2014

Going with the flow

As I return to the German town of my childhood, I’m reminded about the enduring values of resilience, acceptance, and pragmatism.

As I return to the German town of my childhood, I’m reminded about the enduring values of resilience, acceptance, and pragmatism.

Wertheim is nestled between two rivers, the mighty Main with its bustling shipping traffic, and the quieter Tauber, which can still kick up a good flood given the right circumstances, such as rapid snow-melt or excessive rainfall.

As a child here, I was fascinated by the spectacle of “Hochwasser”, that inundation of Wertheim’s streets by the waters of one or both rivers.

As with many towns in Europe (and elsewhere), flooding is a part of historical experience here. There are markings on many of its buildings, showing the years when water had its way, and the only thing there was to do, beyond what pumps can accomplish, was wait for it to recede. Thankfully, after major flooding three years ago, the town has mostly had a reprieve from this annual assault.

Thankfully, after major flooding three years ago, the town has mostly had a reprieve from this annual assault.

Yes, it’s terribly cliché to say that folks here go with the flow, yet after hundreds of years of doing just that, I can see how it has shaped the character of this place. Perhaps it’s part of the reason that those who flowed in from other places — people like my American military family, and thousands of US servicemen, and those who’ve sought refuge from places that had been turned upside-down, or rendered unsafe by war and other calamity — have always found an easy welcome here.

Or perhaps it’s the experience of what the water washes away that has made this a generous and forgiving sort of place.

And the pragmatism?

Well, when the flood waters do rise, and one major thoroughfare becomes a sort of tributary, these canny locals erect raised metal platforms that act as a network of pedestrian paths that thread through the streets “above it all”.

I think this may reflect something of an inner attitude, too.

The following German television segment shares more about Wertheim’s Hochwasser events:

http://swrmediathek.de/player.htm?show=285873e0-9d8a-11e3-826c-0026b975f2e6