Alex Ross's Blog, page 58

August 10, 2020

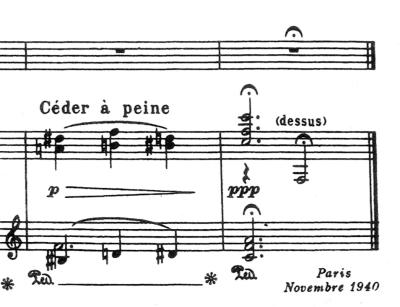

Poulenc's songs

Drunken Angels. The New Yorker, Aug. 17, 2020.

Audio: William Parker sings "Sanglots," from Banalités, with Dalton Baldwin at the piano, from EMI's Oeuvres complètes edition of Poulenc's works.

August 8, 2020

Second dispatch from the mystic abyss

Cyril Kuhn, "Wagner."

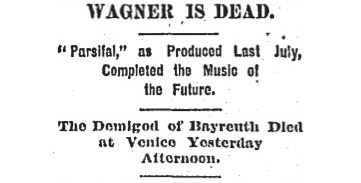

Where to start? With Wagnerism, the point of departure was clear from the outset: Wagner's death at the Palazzo Vendramin, in Venice, on February 13, 1883. There is nothing innovative in beginning a book with a major figure's death, but the import of my three-thousand-word evocation of the worldwide memorials for the composer is less retrospective than predictive: it is in the memorializing of Wagner that the manifold and conflicting strains of Wagnerism, the phenomenon of Wagnerian influence, immediately become visible. Everyone agrees that Wagner was important, but no one remembers him, cherishes him, or condemns him in quite the same way. The so-called Meister dematerializes into competing projections of his work. The noise of his own funeral drowns him out.

From the narrative standpoint, it's useful to begin a large-scale book of this kind not with abstract claims but with an exemplary scene that enfolds certain themes and introduces certain characters. (I think of it as the Barbara Tuchman maneuver — the funeral of Edward VII at the outset of The Guns of August.) My first book, The Rest Is Noise, opens with the Austrian première of Salome in Graz in 1906 — an episode that allowed me to bring on stage Strauss, Mahler, Puccini, Schoenberg and his students, Adolf Hitler, and the protagonist of Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus. Indeed, I chose that setting precisely because the great novelist had gone there before me. With Wagnerism, Mann is again directing behind the scenes. He was undoubtedly thinking of Wagner when he titled one of his most famous stories Death in Venice, even if the composer goes unnamed in that text. And so my Prelude — a nod to Wagner's favored way of beginning an opera — is called "Death in Venice."

As the news of Wagner's death travels the world, we see such diverse figures as Verdi, Mahler, Nietzsche, and Swinburne reacting to it. Sarah Butler Wister's vivid description of a memorial concert in Paris conveys the contentious atmosphere that surrounded the composer even as an attempted deification process was under way. Particularly important is the ominous scene that attended a students' memorial at the Sophiensaal in Vienna — one at which antisemitic rhetoric surfaced, as the Neue Freie Presse noted. That event allows me to introduce the figure of Theodor Herzl, who resigned from the Albia fraternity in protest of the anti-Jewish outbursts. That Herzl loved the music nonetheless confronts us with Wagnerism in its most complex form — the partly alienated fascination of those whom the composer would have regarded as an inferior racial other. W. E. B. Du Bois appears in the introduction in the same guise.

From the Dunedin Evening Star.

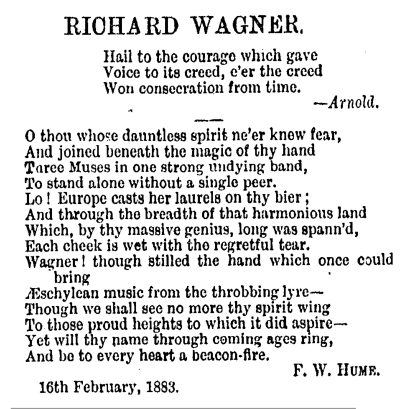

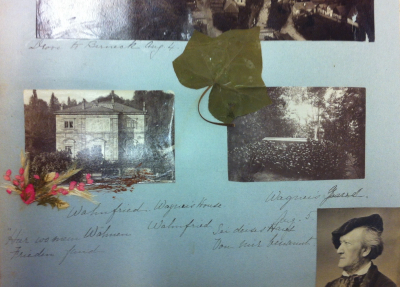

The composition of the prelude required a synthesis of a hundred or more far-flung sources. Much of the research was done without having to leave my desk: mass digitization of newspapers and magazines has exposed the daily fabric of the past to a remarkable degree. In the course of one roaming search I found a Wagner sonnet from Dunedin, New Zealand — a sign of just how far the sorcerer's spell reached. Having noticed that late-nineteenth-century pilgrims made a habit of collecting souvenirs from Wagner's grave in Bayreuth, I found examples in the Isabella Stewart Gardner archive in Boston, the online holdings of the Österreichischer Nationalbibliothek, Éric Lacourcelle's biography of Emanuel Chabrier, and Upton Sinclair's novel King Midas. (In the last, a Wagner pebble disgusts a Brahmsian customs officer.) When it came to Wagner himself in Venice, I relied on the meticulous researches of John W. Barker, who has written not one but two entire books about the composer's relationship with the city, building on Henry Perl's Richard Wagner in Venezia.

Isabella Stewart Gardner's Wagner ivy.

Crucially, I was able to visit the Palazzo Vendramin itself in 2011, during an idyllic month when I was based the American Academy in Rome. Alessandra Althoff Pugliese of the Associazione Richard Wagner di Venezia gave me a tour of the Wagner quarters, During the same period, I blew a certain amount of money on a sea-facing balcony room at the Grand Hotel Excelsior Vittoria, in Sorrento, where Wagner stayed at the time of his final meeting with Nietzsche. This sort of Wagner tourism may not have been strictly necessary to the writing process, but it gave me a certain confidence. Furthermore, various characters in my story had themselves gone on such journeys. Both William Butler Yeats and Andrei Bely went to the trouble of visiting the Grand Hotel et de Palmes, in Palermo, where the score of Parsifal was finished. Alain Locke once took Langston Hughes on a tour of Wagner sites in Venice — in the course of an attempted and apparently unsuccessful seduction.

The author's most Wagnerian moment, in Sorrento.

As I traveled for The New Yorker over the past decade, I was constantly on the Wagnerian prowl. Visiting museums in various cities, I gravitated toward the Symbolist galleries, where something Wagnerish almost invariably lurked. I toured German Wagner cities — Leipzig, Dresden, Munich, and, of course, Bayreuth — and stopped at the sacred-kitsch sites of Ludwig II in Bavaria, including the Starnbergersee, where his body was found. (It is no accident that the Starnbergersee shows up in The Waste Land, a poem wet with Wagnerian allusion.) I went to the Goetheanum in Dornach, which Rudolf Steiner described as a second Bayreuth. And I made several visits to the Wagner sites in Lucerne and Zurich. If Wagnerism has a spiritual home, it is in Zurich, where James Joyce and Thomas Mann, two skeptical Wagnerians, lie buried a few miles from each other. Zurich also happens to be the native town of my friend and German tutor Cyril Kuhn, who was of inestimable help in the final stages of the book. His linotype of Wagner appears at the top of the post.

July 22, 2020

Interview with John Williams

The Force Is Still Strong with John Williams, on the New Yorker website, July 21, 2020.

July 15, 2020

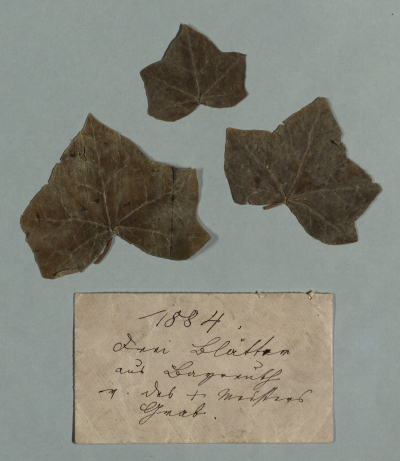

Bruckner's Wagner ivy

Three leaves of ivy that Bruckner collected from Wagner's grave in 1884. From the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

July 14, 2020

Willa Cather's One of Ours

An essay for the New Yorker web site, July 7, 2020.

Video of the day: Beethoven in Karlsruhe

Justin Brown, Karlsruhe's general music director, tells me that he chose the Choral Fantasy for this project because of "the optimism embedded in its fan-shaped construction": solo piano leading to massed instruments and then to voices. Ninety-five performers participated, but there were never more than twenty on stage at once. More details here.

July 5, 2020

Pandemic and protest

Under Pressure. The New Yorker, July 6 and 13, 2020.

June 24, 2020

June 21, 2020

Now playing: Timothy McCormack

This superbly ear-cleansing work appears on a new Kairos CD.

June 16, 2020

First dispatch from the mystic abyss

Giuseppe Becce as Wagner, 1913.

In three months, Farrar, Straus and Giroux will publish my third book, Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music. I thought I'd write a few blog posts describing the genesis of the project and its circuitous voyage toward the appearance of reality. Over the summer, I'll add various auxiliary features to my trusty old website: a general guide to Wagner's works, with recommendations of recordings; a bibliographical essay, touching on topics and sources that fell by the wayside; an index to Wagner on film; and a glossary of Wagnerian jargon, such as "mystic abyss." If I get my act together, I will also present an online chapbook of Bad Wagner Poetry. Whether in-person appearances will be possible in the fall remains to be seen, but we have a string of virtual events scheduled. FSG has an advance excerpt on its Work in Progress blog.

Why Wagner? Why Wagnerism? The two are not the same. When I tell people about the project, they tend to assume that this will be another book about the composer, his life, his work, or some combination thereof. Instead, it's a book about his effect, his impact, his shadow — on literature, the arts, film, popular culture, intellectual life, politics. I make almost no mention of his influence on other composers; in this sense it is not actually a book about music at all. Wagner is present on every page, but often in modified, distorted, sometimes unrecognizable form. It is Wagner as seen and heard through the eyes and ears of an absurdly large and multivarious cast of characters, from Baudelaire to Buñuel, from Willa Cather to Rosa Luxemburg, from W. E. B. Du Bois to J. R. R. Tolkien, from Herzl to Hitler. It is a book around Wagner, after Wagner. It begins with an oblique jest: the man is briefly alive and then falls dead in the fifth paragraph.

As I write in the epilogue — which, in an admittedly contrarian narrative choice, swerves into a personal register otherwise absent from the book — I came late to a full engagement with Wagner. In childhood, I found his music baffling and vaguely revolting. In college, as I studied the intellectual history of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he interested me as a problem, as a crisis. Only in my twenties did I begin to give serious attention to the music itself. And only in my thirties did I begin to understand it, as far as I understood it. The idea for a book about Wagnerism emerged from The Rest Is Noise, which I wrote between 2000 and 2007. I found myself frequently backtracking toward Wagner in order to explain what was happening at the beginning of the twentieth century. When I addressed music in Nazi Germany, the vexed Wagner-Hitler question distracted me at every turn. These persistent hauntings by the old sorcerer of Bayreuth seemed a sign that I should turn toward him next. So I offered up Wagnerism as a topic to my publisher in 2008. First I put together my essay collection, Listen to This. I also went through a phase of listening to all of Wagner's works with scores and reading his all-too-voluminous prose writings. I began writing in August 2010; I submitted the finished draft last September; I sent in final changes last week.

The journey took so long because the territory is so huge. Wagner was all but unavoidable for artists working at the turn of the last century, and few evaded his inky shadow. The phenomenon of Wagnerism — defined here as the composer's influence on the arts — has elicited an extensive and rich literature. There are books about Wagner and Mallarmé, Wagner and Joyce, Wagner and the British novel, Wagner and the visual arts, Wagner and modernism, and so on. Dozens of books have studied his relationship with antisemitism and Nazi Germany. What struck me, as I surveyed my shelves, was that no one had really attempted to pull all of these diverse Wagnerian discourses into a single volume. There was, to be sure, Timothée Picard's 2500-page Dictionnaire encyclopédique Wagner, which I acquired a year or so into my researches, and which delayed the process for at least a year longer as I fell into a mesmerizing and sometimes alarming subculture of lesser-known French writers who had spelunked the Wagner caves. Marcel Batilliat's incomparably creepy novel Chair mystique, which ends with a scene of what can only be described as amatory decomposition, made a not entirely welcome entrance into my life. Could the sort of omnivorous overview undertaken by Picard and his team of authors be accomplished in a narrative of under a thousand pages? I thought it was worth a try. I now understand why it had not been done: it is impossible. Wagnerism, as long as it is, is far from being comprehensive. Big swaths of material go untouched, not least because of limitations of language; I can read only French and German. I caught passing glimpses of Italian Wagnerism, Polish Wagnerism, Portuguese Wagnerism, Latin American Wagnerism, but could not stop and explore.

The project also took a long time because I enjoyed the research phase so deeply. It has been, as I say in the introduction, the great education of my life. I read and re-read hundreds of books, some directly related to the work, some more tangential. I took the opportunity to read everything by Willa Cather, everything by Virginia Woolf. I watched at least a hundred films; I stopped at museums as I traveled; I delved into the archives of lesser-known figures like Sidney Lanier and Owen Wister; I followed Wagner's footsteps in Italy. Alongside myriad discoveries, I brought to bear longtime obsessions, going back to university or even high-school days. Not a sentence of my senior thesis on James Joyce proved to be reusable, but I did consult some yellowed notes on Joyce's relationship with the work of Otto Weininger, unhappiest of Wagnerites. (Sign of aging: when papers from one's past become parchment.) What excited my attention were unexpected links between artists in far-flung places: how Philip K. Dick recapitulates themes from Joséphin Péladan, how both Marcel Proust and Francis Coppola associate aerial combat with "The Ride of the Valkyries."

The book is structured so that the grimmer side of Wagner's influence comes to the fore in the middle sections. In the first third, the reader may have the sensation of touring a kind of delirious theme park of fin-de-siècle decadence; but in the chapters on Wilhelmine Germany and on Wagnerian antisemitism, the shadow grows cold. Hitler enters in the tenth chapter, as a young man who flounders as an artist and then finds purpose in war. Nazi Germany occupies the thirteenth chapter, in counterpoint to the later work of Thomas Mann. I hope to replicate for the reader a feeling of harrowing descent. The disaster is not absolute; new varieties of Wagnerism surface in the final chapters, in Dick, Ingeborg Bachmann, Terrence Malick. I resist any blunt equation of Wagner and Hitler; the former was a kind of monarchical anarchist, the fascist state foreign to his hazy political vision. Nonetheless, the Nazification of Wagner was not some sort of unfortunate accident that befell a "great artist." I end the book by proposing that the monstrous complexity of that connection is what makes Wagner a perennially relevant case. Working through the problems he has created is the kind of labor we must always undertake when art collides with reality, as it inevitably does. The fundamental error is in assuming that art and reality are separate to begin with.

There, then, is the general lay of the land. In future posts I'll say more about the researching and the writing. I'll close this first post-mortem dispatch by expressing desperate gratitude to my editor, Eric Chinski. He presided over the cutting of around a hundred thousand words from the initial draft — not as catastrophic as the Rest Is Noise situation, but bad enough — and provided crucial guidance in getting the remainder under a semblance of control. I have always been lucky in my editors; I would be nowhere without them.

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers