Alex Ross's Blog, page 54

January 14, 2021

A Percy Grainger moment

An extraordinary recording, one of John Eliot Gardiner's finest.

January 11, 2021

Respite

In a stream from Wigmore Hall, members of Apartment House play Feldman's Piano and String Quartet.

David Hockney's Wagner Drive

Road Trip. The New Yorker, Jan. 18, 2021.

Below are directions for the first of David Hockney's Wagner Drives, the Malibu Canyon version. The Adrian Boult recordings that Hockney used are not easily available, but substitutes with similar timings are suggested below.

1. Begin at the corner of Las Flores Canyon Road and Pacific Coast Highway. Play "America" from West Side Story. Repeat if necessary until step 2.

2. Turn right onto Malibu Canyon Road. Play "The Entrance of the Gods into Valhalla" from Das Rheingold, duration 8:49. Suggested recording: Gustavo Dudamel conducting the Simón Bolivar Symphony Orchestra (DG).

3. Turn right onto Piuma Road; after 6.4 miles, continue briefly onto Rambla Pacifico. Play the Prelude to Act I of Parsifal, duration 12:45. Suggested recording: Georg Solti conducting the Vienna Philharmonic (Decca).

4. Turn left onto Las Flores Canyon Road and return to the PCH. Siegfried's Funeral Music from Götterdämmerung, duration 8:14, should be beginning at about this time. Suggested recording: Gustavo Dudamel / Simón Bolivar (DG).

The Kanan Dume drive is more difficult to replicate, but I've traced the route on Google Maps. The playlist is: "America," "Blue Danube" Waltz, Entrance of the Gods (at the turn onto Kanan Dume), Parsifal Act I Prelude, Parsifal Act I Transformation music, Parsifal Good Friday music, Siegfried's Funeral Music, Parsifal Act I Prelude.

Directions for the San Gabriel drive are here. The playlist is: three Sousa marches (Hands Across the Sea, The Thunderer, The Belle of Chicago), Entrance of the Gods, first movement of Schumann's "Rhenish" Symphony, Parsifal Act I Prelude, second movement of the "Rhenish," Sousa's Liberty Bell march.

Much thanks to Arthur Kolat for making these expeditions possible. His excellent thesis Twilight of the Roads can be found at Academia.edu.

January 8, 2021

The marginal lament of a DC native

To be from Washington, DC is in some sense to be from nowhere. There is no DC accent, no identity. The city's population is too malleable and transient, it seems, for such markers to take hold. Nevertheless, none of us can escape a visceral attachment to the place from which we came. Some usually inactive nerve of DC-ness, of DC pride, was touched by the grotesque and appalling images that came out of the US Capitol yesterday. I am not in the habit of shouting expletives at the television, but so it turned out. It didn't seem possible that I could loathe this pestilential president even more than I had loathed him the day before, but so it turned out.

My father grew up in the city and worked for the government his entire career, at the US Geological Survey. My late mother worked part time for the Smithsonian Institution, at the National Museum of Natural History, on the Mall. She also volunteered at the White House during the Bush and Obama administrations. These somnolent, seemingly impregnable monuments were always in the background of my youth, though I very seldom ventured inside them. My only visit to the Capitol, as far as I can recall, was for a second-grade field trip in which we were given a tour by Senator Edward Kennedy, one of whose sons was in my class. We sat at desks in the Senate chamber, but I remember being most impressed by the underground train that carried people from one part of the complex to another.

My rage at Wednesday's events gave way to tears when I tried to imagine my mother's reaction to them. She was deeply devoted to Washington's ceremonial trappings and architecture. We had dozens of books about the White House, the Capitol, and other buildings on the mall. She was also politically very conservative. I don't know if she would have accepted any of the right-wing justifications or distortions that are circulating around the terrorist incident at the Capitol, but I am certain that the sight of democratic symbols being violated and destroyed would have caused her very intense distress. I can't help feeling the same, even if the physical damage is incidental to the lives that were lost, and even if the entire circus-like spectacle drove home the concept of white privilege in incontrovertible fashion.

January 5, 2021

A Jürg Frey moment

This new work by Frey, played by violinist Anouck Genthon and gambist Pierre-Yves Martel, takes its title from a poem by the Swiss poet Anne Perrier: "Ce chant trop lourd / Je laisse à la nuit son poids d’ombre / Et le reste / Je le donne à l’espace / Qui le donne à l’oisseau qui le donne / A l’ange éblouissant." Or: "This too heavy song / I leave its weight of shadow to the night / And the rest / I give to space / Which gives it to the bird which gives it / To the dazzling angel."

December 24, 2020

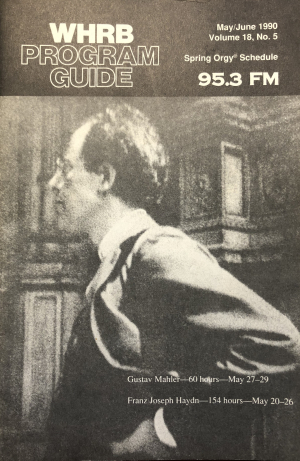

David Elliott tribute on WHRB

Today I've been listening raptly to WHRB's David Elliott Memorial Orgy, a tribute to Harvard radio's spiritus rector, who died last month at the age of seventy-eight. It was a melancholy joy to hear again David's mellifluous, unpretentious, effortlessly knowledgeable voice. Was there was ever a finer announcer of classical-music radio? I know of none. But he was a great deal more than that; he was an educator of rare ability, a mentor of unstinting generosity, one of the most selfless people I have ever met. In a segment aired toward the end of the program, I tried to convey my gratitude to and for David, without whom I would probably have never become a music critic. Here's the audio I sent to Allison Pao and Xilin Zhou, two Harvard undergraduates who managed the brilliant feat of putting together the program and sending it out remotely:

Many more memories came to mind as I listened to dozens of alumni, performers, listeners, and friends extol David. What he created at the station was an atmosphere of dedication, seriousness, and thoroughness, which applied not only to classical music, his primary interest, but also to folk, jazz, rock, and R&B. Each department had a particular identity, a sense of mission, and whether or not David liked the music in question — he blanched at the ruder eruptions of post-punk rock and hip-hop — he appreciated anyone who was pursuing a topic assiduously. When, for example, my friend Jason Shure went to superhuman lengths to pay tribute to Captain Beefheart, he earned David's respect, if not his comprehension. Obsession was the rule during the winter and spring "Orgy" periods — orgies being multi-hour or in some cases multi-day explorations of a composer, artist, band, ensemble, genre, or period. Orgies are said to have begun when a student expressed relief at having finished his exams by playing all nine Beethoven symphonies in a row. Thanks primarily to David's influence, such stunt-like escapades became ambitious undertakings of research and preparation. Shortly before I arrived at WHRB, the station aired a complete traversal of the works of J. S. Bach, with Prof. Christoph Wolff serving as scholarly adviser. Nothing quite like it had taken place anywhere; David and Michael Rosenberg, who produced the program, were able to make use of Hänssler Classics recordings of cantatas that had just been issued.

My somewhat maladjusted post-adolescent temperament was immediately drawn to these exercises in exhaustiveness. David recognized me at once as someone who would join him in his quest to uncover little-known composers, neglected performers, and obscure oddities of all kinds. Although he loved the core repertory as much as anyone, he refused to let WHRB become the sort of easy-listening classical station that would play snippets of Vivaldi and greatest hits of Mozart. Indeed, there was a list of "warhorses" that were more or less forbidden, although they were allowed to run rampant on a semi-annual Warhorse Orgy. I inherited from David a wide-open conception of the classical repertory, running from the deep past to the present. There was never the one perfect recording. Whenever I fastened on to a favorite — say, Karajan's Mahler Ninth — he would say, "Have you heard Bruno Walter live from Vienna?" I might have stuck with my Karajan, for the time being, but the interplay of alternatives was all important. As historically informed performances of Baroque music came to the fore, he retained a charming fondness for the likes of Alfred Cortot's Brandenburgs, Malcolm Sargent's Messiah, and Klemperer's St. Matthew Passion. I have a distinct memory of him listening in awe when the Passion came on the air. As I was bustling on to some pressing task, he said, "Just listen!"

During my time at WHRB, I presented two weekly shows, the Twentieth-Century Symphony and Music Since 1900, and hosted a procession of orgies, including complete surveys of Britten, Shostakovich, Brahms, and Nielsen, as well as a multi-genre program called the Avant-Garde of the 70s and 80s, with sections on jazz and experimental rock curated by Mike Pahre and Mike Vazquez. David's vast record collection would fill in many missing gaps in these programs: only he could have come up with Shostakovich's Moscow, Cheremushki or Britten's Paul Bunyan (yet to be commercially recorded, but David had an off-the-air tape). The orgies would include historical-performance sections, for which David usually served as guest announcer. (I could not, of course, announce for 50 or 60 hours straight, though I would stretch the limits of what was possible.) I remember in particular the impeccable segment on Mahler's Singers that he added to my final WHRB project, Mahler and the Fin de Siècle: rare discs of Anna Bahr-Mildenburg, Leopold Demuth, Selma Kurz, Leo Slezak, and Richard Mayr. I spent so many hours chatting with David, looking over Schwann record catalogues, browsing the Harvard Music Library catalogue, plotting how to obtain the seemingly unobtainable. It was in David's spirit that I ended up writing to György Ligeti, hoping to locate a recording of the Poème Symphonique for 100 Metronomes. Ligeti duly told me how to find one — a letter that I subsequently lost, to my eternal regret.

At times, this pursuit of the esoteric became absurd. Not until WHRB's 75th-anniversary celebration in 2015 did I discover that David had recorded a delirious moment from my Nielsen Orgy of January 1990. He proceeded to play that tape to the anniversary gathering, sending me into a vertiginous state of pride and embarrassment blended. What happened was that I had listed in the program guide a recording of Nielsen's final finished work, the 30-second-long Piano Piece in C, Fog-Schousboe 159. It was supposed to appear on Hyperion's two-CD set of Nielsen piano music, with Mina Miller at the keyboard. But when I got out the discs I was bewildered to find that the tiny piece was not there. I made this discovery just before the the final section of the program, which presented legendary symphonic performances by Thomas Jensen, Launy Grøndahl, and Erik Tuxen. David, observing how crestfallen I was by the absence of FS 159, came up with a crazy plan: why not find the score at the Harvard Music Library and make an instant recording? I was no great shakes as a pianist, but the music was brief enough, and simple enough, for me to tackle. During Grøndahl's Second Symphony, I ran to the library to check out the score, and during Tuxen's Fifth I ventured with David to the Adams House Junior Common Room to make the recording. This is what ensued on air:

It's doubtful that anyone would have cared if the Piano Piece in C had failed to appear, but at that moment it mattered to me immensely. David took obvious delight when the students were seized by manias of this kind, which set WHRB apart from every other station. I thank him for having cultivated my obsessive drives, directed them, put them to constructive use. What he did for me is what all great teachers do. And, although he had no official role in the money-devouring monster that is Harvard University, he was one of the two best teachers I encountered there — one of the best teachers I ever had.

December 19, 2020

Year in writing

I wrote four longer pieces for The New Yorker this year: an article about the Great Basin Bristlecone Pine, in January; an essay about the German-speaking emigration in L.A. in the 1930s and 40s, in March; a profile of the pianist Igor Levit, in May; and an essay on white supremacy in classical music, in September. I also fashioned a piece on Wagner in Hollywood from the final two chapters of my book Wagnerism, which appeared in September. My Musical Events columns touched on Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony, the LA Phil's Weimar Republic festival, The Flying Dutchman and Agrippina at the Met, Yuval Sharon's Sweet Land in L.A., CDs by Víkungur Ólafsson and Liza Lim, online marathons by the Met and Bang on a Can, new music after George Floyd, Poulenc's songs, the LA Phil at the Bowl, Jennifer Walshe, Sharon's Twilight: Gods, and virtual orchestral seasons. My online contributions included a year-end list, a piece on Hitler in the bunker, short notes about Nick Neely's Alta California and Garth Greenwell's Cleanness, a look at the Spektral and JACK Quartets, a meditation on Billy Budd and Beau Travail, an examination of the ecological cost of recording, an interview with John Williams, a piece on Willa Cather's One of Ours, and a musical memorial for my mother, who died in February. Deep thanks to all who found time to read my work in this horrendous year, and still deeper thanks to The New Yorker for giving me the space and time to write.

December 18, 2020

Dawn in Panamint Valley

As a reward for the end of the long haul with Wagnerism, I spent a week in the area of Death Valley, my favorite place on earth. Based in the lovely town of Shoshone, I passed several lazy days reading Don Quixote, watching Antonioni movies, and observing the play of color on the Resting Spring Range. My major expedition involved renting a Jeep Wrangler Rubicon from Farabee's and driving up to Urehebe Crater, where I went on to the Racetrack road. I hadn't seen the Racetrack playa, with its famous sliding rocks, and Teakettle Junction (I performed the obligatory teakettle exchange). I then followed the White Top Mountain Road and hiked a bit at the top of Bighorn Gorge before going back south on the Hunter Mountain Road. I camped on Lake Hill Road in Panamint Valley — a new moon enabled the most extraordinary night sky I've seen since I was in Djibouti in 1999 — and began the second day driving down the Trona-Wildrose Road (photo above). I went off pavement at Ballarat and made my way over to the Goler Wash, driving behind mining trucks that sent up photogenic plumes of dust in the dawn sun. At the top of Goler Wash I made the inevitable stop at Barker Ranch and then ascended to Mengel Pass, trusting my Farabee's beast to handle an alleged road that consisted mostly of piles of rock. It did not fail. Butte Valley was the reward on the other side, with the geological wonder of the Striped Butte at its heart. I went down Warm Springs Canyon and got on the West Road. With an hour or so remaining before sunset, I branched off on the Trail Canyon Road and briefly explored one of the canyons at the top. Back in Shoshone, I resumed inactivity, though I spent one day hiking the gorgeous trails of China Ranch and driving in the Nopah Range wilderness. This was my tenth trip to Death Valley, but there's still so much more to see. My next goal will be the far north part of the park. Deepest thanks as ever to Darrel Cowan.

December 17, 2020

A Trevor Bača moment

Bača's ( H A R M O N Y ), from a Monday Evening Concerts event in January 2020. Paul Holdengräber recites Paul Griffiths's text; Jonathan Hepfer leads the Echoi ensemble.

Alex Ross's Blog

- Alex Ross's profile

- 425 followers