Leonide Martin's Blog: Lennie's Blog, page 5

October 31, 2015

Los Muertos, Hanal Pixan, and Brujos

Mexican and Mayan Traditions for Honoring the Deceased.

Mexican and Mayan Traditions for Honoring the Deceased.Dia de Los Muertos is a well-known celebration in Mexico, taking place on October 31-November 2. It’s often considered the Latino equivalent of Halloween, but there are many important differences in these traditions. For Mexicans, Dia de Los Muertos is a time to remember and honor family and friends who have passed, accompanied by altars with pictures, special foods, and

Mexican Dia de Los Muertos Altar

visits to cemetaries. The Western tradition of Halloween focuses upon the scary and eerie aspects of the departed, when the veil between worlds becomes thin and visitations from ghosts more likely. In addition, there’s the Trick or Treat phenomenon, when children dressed in costumes bang on neighborhood doors demanding candy. If none is forthcoming, they’re supposed to do a trick such as toilet-papering your bushes.

Before the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, Los Muertos was at the beginning of summer. It was moved to the present date to coincide with the Christian traditions of All Saints’ Day, also called All Hallow’s E’en (which morphed to Halloween). Mexican traditions include building private altars (ofrendas) decorated with sugar skulls and marigolds, with plates of the deceased’s favorite

Two Catrinas Mexican Saints Skeletons

foods and beverages. They also visit graves with gifts, and bring possessions of the deceased to graves. Origins of the modern Mexican holiday can be traced to indigenous observances dating back hundreds of years, with distant threads to an Aztec festival dedicated to the goddess Mictecacihuatl.

Mayan Traditions: Hanal Pixan

Mayas in southern regions of Mexico have a tradition called Hanal Pixan (Food for the Souls). It is similar to Los Muertos as they build family altars, where they place pictures of the deceased, flowers, candles, favorite food and drink, and possessions. In Yucatan this has traditionally been a private celebration, but cities are encouraging Mayas to take part in public ceremonies that attract many tourists. Homes are swept and cleaned in anticipation of visits from ancestors’ souls, who rise from their graves during these nights to visit their families and homes. Tradition holds that if they don’t find the house

Mayan Hanal Pixan Altar

clean, they feel obliged to stay and help with cleaning. After altars are set up in the house, the family sits respectfully, often saying prayers or sharing remembrances. Later they have a feast, eating and drinking the special foods and liquors on the altar. In Merida, the capital of Yucatan, there is a Friday night event at L’Ermita colonia and a Saturday daytime event in the Plaza Grande in Merida Centro. Mayan groups build pole and thatch sheds in plazas, and put elaborately decorated altars inside. These pictures show typical Yucatecan Maya costumes and clothes (women in huipiles).

A charming tradition for Hanal Pixan tries to capture evidence of the departed soul’s visit. When the altar is completely decorated, fine cornmeal is scattered around in front of it. Everyone is careful to stay away from the cornmeal, which is left overnight. In the morning, if there are footprints left in the cornmeal, this is taken as evidence of a soul’s visit. In Yucatan special foods are prepared, based on ancient Mayan cuisine. The culinary delight of this celebration is mucbil pollo, commonly called pib (or pibe). The pib is a pit dug into the ground, in which a fire of logs is burned to glowing coals, then seasoned prepared meat (typically chicken or pork) is covered with masa (cornmeal) wrapped in banana

Mucbil pollo (pib)

leaves and put inside the pit, which is filled with soil, and left to slowly bake for hours. Much preparation is required for this favorite food, when cooked traditionally as did the ancient Mayas (their meats were turkey, tapir and deer). Other foods include black beans cooked and pureed, tomatoes, corn, squash, and typical Yucatecan dishes such as papadzules, a corn tortilla filled with chopped hard boiled eggs and covered with a rich sauce made of ground pepitas (pumpkin seeds). Que rico!

Although the Mexican tradition of brujos is not connected with Los Muertos or Hanal Pixan, this term refers to sorcerers, magicians or witches and seems in keeping with a Halloween-type theme. Especially among the Mayas, every village has its brujo or bruja, a male or female sorcerer whose powers can be used for good or evil. The history of magical practices extends back to pre-Hispanic times and has shamanic roots. As currently practiced, these magical abilities combine Catholic rites, especially the invocation of saints,

Mayan Shaman or Brujo

Ancient Mayan Ceremony

with ancient Mayan beliefs and rituals. The brujos are much feared and respected by Mayas, their services sought when illness such as mal ojo happen. Mal ojo means “bad or evil eye” and is thought to be caused by a sending looks of evil intention at someone, usually a child. Brujos can be hired to both cause and cure mal ojo, and many other spiritual illnesses. When an illness is caused by a brujo or bruja, only another brujo/bruja can reverse or cure it. Villages also have h’men, a title for healers who use plant medicine, and are benign figures who also perform beneficial ceremonies such as calling the rain, the Cha-Cha’ak ceremony.

Here is a link to a Merida magazine, Yucatan Living, with an article about Hanal Pixan.

http://www.yucatanliving.com/daily-life/hanal-pixan-in-merida#

October 14, 2015

Who Was the Mayan Red Queen? Part 2 – The Evidence of Her Life

The Mayan Red Queen

The Mayan Red Queen continued to be an enigma to archaeologists for nearly two decades after her tomb was discovered in Temple XIII at Palenque in 1994. Her skeleton and inside of her sarcophagus were coated with red cinnabar, a mercuric oxide preservative used in royal burials. This led archaeologists to nickname her “The Red Queen.” It also made analysis of her bones and teeth difficult, and many years passed until scientific techniques advanced enough to provide reliable data. The lack of inscriptions and the sparse ceramic evidence found inside her tomb further muddied the waters. Most Mayan royal tombs contained carved or painted hieroglyphs identifying who was interred. The adjacent pyramid tomb of K’inich Janaab Pakal in Palenque was full of hieroglyphic records; his ancestors were carved on the sides of his sarcophagus, important gods and mythohistoric figures were painted on the crypt walls, and the sarcophagus lid clearly identified him. Numerous ceramic offerings allowed dating of the interment to the late 600s AD.

Pakal’s Sarcophagus Lid

The situation of the Mayan Red Queen was quite different. Her sarcophagus contained no inscriptions, the crypt walls were bare, and

The Mayan Red Queen’s Sarcophagus

ceramics few. The shape and characteristics of the censer, vases and plate found in her tomb corresponded to the Otolum ceramic complex, which has been placed between 600-700 AD. Her life overlapped with that of Pakal, and her pyramid tomb adjoined his, so it seemed evident that there was an important connection between them. Additional corollaries in their burials include a monolithic lidded sarcophagus inside a mortuary crypt, jade masks, diadems, jade beads, pearls and three small axes in a ceremonial belt. Both skeletons and insides of their sarcophagi were painted red with cinnabar. Two significant women in Pakal’s life died in that time period: his mother Sak K’uk and his wife, Tz’aakb’u Ahau. Some archaeologists believed the Red Queen was his mother; others favored his wife. In 2012 the mystery was most probably solved when DNA studies revealed that The Red Queen and Pakal did not share common DNA. This was further supported by strontium isotopes studies conducted a few years earlier showing that the two grew up in different areas within the region. Now most agree that Pakal’s wife, Tz’aakb’u Ahau, was interred in Temple XIII and she is The Mayan Red Queen.

What do we know of her life?

West Tablet from Temple of the Inscriptions

Linda Schele – Mesoweb

Unfortunately, very little evidence has been found so far. Palenque is famous for its high quality, graceful hieroglyphs and realistic carved figures. The Three Tablets of the Temple of the Inscriptions (Pakal’s burial pyramid) contain 617 glyphs, one of the longest Maya inscriptions known. The West Tablet, covering the later years of Pakal’s reign, contains two references to her:

“Seventeen days after the 3 Ahau 3 Uayeb (Period Ending), Lady Tz’aakb’u Ahau was married on 7 Caban 15 Pop.”

“Forty-seven years after she became queen, Lady Tz’aakb’u Ahau passed away on 5 Etznab 6 Kankin.”

These follow lengthy descriptions of actions taken by Pakal, and the dates are tied into the Long Count calendar by use of a Distance Number to the nearest Period Ending, which was 9.9.13.0.0 (3 Ahau 3 Uayab) or 626 AD. These later passages of the West Tablet were commissioned by their oldest son, K’inich Kan Bahlam II, after his father’s death. He recorded the marriage and deaths of his mother and father.

Tz’aakb’u Ahau is depicted in carvings on two tablets from Palenque. The Palace Tablet has carved relief figures showing her third son, K’inich Kan Joy Chitam II, seated on a double-headed serpent bar, receiving the headdress of royalty from his father Pakal, as his mother (Tz’aakb’u Ahau) offers him the god-figurine symbol of divine ancestry. This large tablet filled with rows of hieroglyphs originally adorned the rear wall of the Palace’s northern gallery, Houses A-D. The Dumbarton Oaks tablet shows a young K’inich Kan Joy Chitam II dancing in the guise of the rain god, flanked by his mother and father. This is the only surviving part of a larger composition that probably was surrounded by glyphs. The stone tablet was illicitly removed from an unknown temple in the mid-20th century; it now resides in Washington, DC.

The Palace Tablet

Pakal – Kan Joy Chitam – Tz’aakb’u Ahau

Dumbarton Oaks Tablet

Tz’aakb’u Ahau – Kan Joy Chitam – Pakal

Such fragments of evidence give a little knowledge of The Mayan Red Queen’s life: she came from a nearby city, married Pakal in 626 AD, bore him four sons, participated in accessions rituals symbolically after her death, and died in 672 AD, eleven years before Pakal’s death in 683 AD. She was buried regally in a smaller temple adjacent to Pakal’s.

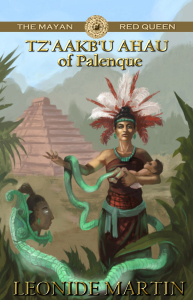

Would you like to know more about what her life might have been? Her imagined story is told in my historical fiction book The Mayan Red Queen: Tz’aakb’u Ahau of Palenque.

It has been nominated for a 2016 Global Ebook Award!

September 24, 2015

The Red Bones Speak

Skull of The Mayan Red Queen

Revelations of the Mayan Red Queen’s skeleton about who she was.

It took ten years after the discovery of the Mayan Red Queen’s skeleton in 1994 for archeologists to make progress on her identity. They had narrowed the candidates to four royal women, all connected to K’inich Janaab Pakal, but who she was eluded them. Since the Red Queen’s tomb was found in a small pyramid adjacent to Pakal’s magnificent Pyramid of the Inscriptions holding his burial chamber, it was clear that she must be closely connected with this famous ruler. There were no inscriptions on the sarcophagus or walls of the crypt to indicate the identity of the interred woman. The candidates were:

Yohl Ik’nal, his grandmother – Heart of North Wind

Sak K’uk, his mother – Resplendent White Quetzel

Tz’aakb’u Ahau, his wife – Accumulator of Lords

K’inuuw Mat, his daughter-in-law – Sun-Possessed Cormorant

Early on, Pakal’s grandmother was eliminated because she died more than seventy years before the Red Queen’s tomb was built, and archeologists determined it was not a secondary burial. Both his mother and wife died within the time frame, and possibly the daughter-in-law, although her date of death is not known. The bones were permeated with red mercuric oxide called cinnabar, used as a preservative by ancient Mayas. The bright red color also symbolized sacred energies of blood, called itz. It was the color of the east, the rising sun, the renewal of life eternal. Cinnabar made the bone cells very difficult to examine microscopically, and the bone matrix had deteriorated over time.

Strontium isotopes analysis. Between 1999 and 2003, a project under the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) extracted samples of bone and teeth from both Pakal and the Red Queen. Studies of strontium isotopes were done by Dr. Vera Tiesler and Dr. Andrea Cucina, of the Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan (UADY) during those years. Strontium isotopes are found in

Strontium isotopes in various geological strata

bedrock, and vary with the age and type of rock. Isotopes move from rock into soil and groundwater, into plants and through the food chain. In humans, strontium isotopes in skeletal bones reflect diet during the later years of life; those in tooth enamel indicate diet during childhood. Geologically different regions will have different isotope ratios. When the isotope ratios of Pakal’s bones and teeth were examined, these showed he was born and resided in later life in the Palenque region. The Red Queen’s tooth enamel had isotope ratios of a different geographic region located in the western part of Veracruz, making it likely that she came from Tortuguero or Pomona. Epigraphic evidence also indicates she was from a different city than Palenque. The strontium isotopes studies made it unlikely that the Red Queen was Pakal’s mother, who was born and lived her life in Palenque.

DNA Double Helix

DNA analysis. More definitive evidence that the Red Queen was not Pakal’s grandmother or mother came from DNA studies completed several years later. Dr. Carney Matheson at Lakehead University in Canada studied several bone samples from Pakal, the Red Queen, and three other individuals from Palenque. His group specialized in studying biomolecules and the processes of their degradation, especially focusing on ancient biological remains that were challenging to recover using conventional methods. In June 2012, INAH released a statement with the DNA analysis results that “confirmed that there was no relationship between the Red Queen and Pakal.” They did not have common DNA, so she was not a blood relative. Most Mayanists now believe his wife, Tz’aakb’u Ahau, was the Red Queen. There is still a slight chance it might be his daughter-in-law, or another unrelated woman. If future excavations discover the tomb of one of Pakal’s sons, DNA studies on those bones would confirm the red skeleton’s identity as Pakal’s wife. Of interest, the Red Queen’s bones were returned to

DNA Analysis in Lab

Palenque in 2012, after residing in Mexico City since their discovery in 1994. Placed in several carefully sealed boxes, her bones are kept in the archeological zone in a structure where humidity and temperature can be controlled. Her burial chamber in Temple XIII has too much humidity and temperature fluctuation to safely house the bones and prevent further deterioration. Her empty sarcophagus can be viewed in its chamber, still coated with cinnabar.

Temple XIII – small pyramid to right of Temple of Inscriptions

Read the story of The Mayan Red Queen in well-researched historical fiction. Compelling depiction of her life with Pakal at Palenque (Lakam Ha) during its height as a creative and political vortex.

September 5, 2015

Who Was The Mayan Red Queen? Part 1 – The Candidates

Red Queen’s Skeleton in Sarcophagus

Part 1 – The Candidates For the Mayan Red Queen.

“The Red Queen” was the nickname given by archeologists to the red cinnabar-permeated skeleton of a tall woman, covered with jade and shells, found inside a sarcophagus whose inner walls were also coated red. They knew she was someone important, probably royalty related to famous Maya king K’inich Janaab Pakal, since Temple XIII which contained her sarcophagus was adjacent to his burial pyramid in Palenque. After an expert Mexican physical anthropologist determined the skeleton was female, speculation ran rampant over who she was. Discovering her identity would be difficult, however, because the crypt and sarcophagus did not have any inscriptions. This was surprising, since Pakal’s crypt walls, sarcophagus walls and lid were literally covered with Maya hieroglyphs, symbols and portraits of ancestors. The process of deduction led to identifying four candidates in Pakal’s family. From Pakal’s burial, tablets and panels we know the names of his mother and grandmother. From panels in the Palace and Temple of the Inscriptions we can identify the names of his wife and daughter-in-law. He apparently did not have any sisters or daughters, although he did have four sons.

The candidates for The Red Queen were Pakal’s grandmother, mother, wife and daughter-in-law.

Yohl Ik’nal Portrayed on Pakal’s Sarcophagus

Yohl Ik’nal was the grandmother of Pakal. Her birth date is not known, but the glyphs recorded that she ascended to the throne of Palenque in 583 CE. She was the first Mayan woman to rule in her own accord, and most probably inherited rulership from her father, Kan Bahlam I. She ruled successfully for 21 years, fending off attacks from Kalakmul and bringing prosperity and new constructions to her city. Although there is disagreement among Mayanists about dynastic succession, the interpretation I’m following holds that Yohl Ik’nal was the mother of Aj Ne Ohl Mat, a son who ruled from 605-612 CE, and Sak K’uk, a daughter who ruled from 612-615 CE.

Sak K’uk depicted on Palenque Palace Tablet

Sak K’uk was the mother of Pakal. She was born around 578 CE, and became the second Mayan woman to rule in her own right. She took over during a chaotic

period in Palenque, when the city suffered a devastating defeat by Kalakmul near the end of her brother’s reign. After he was killed, the city was without leadership and in spiritual crisis, because their sacred portal to the Gods and Ancestors (the Sak Nuk Nah–White Skin House) had been destroyed. Sak K’uk managed to assume the throne and hold it until her son, Pakal, was 12 years old and acceded. It’s highly likely that she continued to provide leadership for several more years.

Tz’aakb’u Ahau Portrayed on Palenque Palace Tablet

Tz’aakb’u Ahau was the wife of Pakal. Her birth date is unknown; they married in 626 CE. Born in a neighboring town, very little is recorded about her. She bore Pakal four sons, two of whom became rulers. She is depicted on the Dumbarton Oaks tablet sitting with Pakal on either side of their second son to rule, K’inich Kan Joy Chitam, and again on the Palace Tablet tendering him the symbols of divine ancestry. Her death in 673 CE is recorded in the Tablets of the Temple of the Inscriptions. An image that many consider to be her appears on the inner piers of that Temple, cradling the lineage deity Unen K’awiil (of the Palenque Triad Deities).

K’inuuw Mat Name Glyph

K’inuuw Mat was the daughter-in-law of Pakal. She married Pakal’s youngest son, Tiwol Chan Mat (647-680 CE.) Although two of Pakal’s older sons ruled, neither of them left heirs. Succession passed on after the last brother died to the nephew of the previous kings. We know almost nothing about K’inuuw Mat, except that she was not from Palenque. Her son K’inich Ahkal Mo’ Nab III continued Pakal’s dynasty by acceding to the throne in 721 CE.

The lives of these Mayan queens are told in compelling historical fiction in The Mists of Palenque series. www.mistsofpalenque.com

August 29, 2015

An Archeologist’s Dream Discovery

Temple XIII at Palenque (c.1990)

Situated between Temple of the Inscriptions and Temple of the Skull

Entrance to Temple XIII – Leonide Martin under thatched roof (2012)

Temple XIII, Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico

On the morning of April 11, 1994, a young archeologist named Fanny Lopez Jimenez was doing routine work clearing weeds and debris off the collapsed stairs of Temple XIII. Her goal was to stabilize the structure and prevent further deterioration. She stood at a distance observing her work, and noticed a small crack about 4 cm size, partially covered by masonry. Using a mirror first and then flashlights, Fanny and co-workers directed light into the fissure and peered in, seeing a narrow passage 6 meters long. The passage was empty and clear of debris, and opened onto another passage running at right angles. Where the two passageways met, they saw a large sealed door. Fanny could hardly contain her excitement. She had found an unknown substructure

Temple XIII Interior Chamber with Corbelled Arch

buried inside the surface of Temple XIII, a building no one thought had anything important to offer. After getting project director Arnoldo Gonzales Cruz’ okay, her team chipped away stones and entered the passage the next day. As she climbed through the opening, she felt as though she entered “a tunnel of time,” her footsteps falling upon the silence of centuries, echoing off slumbering walls long mute. They entered a 15-meter gallery built with large limestone blocks that had three chambers. The two side chambers were empty; the central one was closed off by precisely fitted stonework covered with a coat of stucco that still had traces of black pigment. At either end of the gallery were sealed doorways. The tall ceilings were constructed using the Maya corbelled arch, a triangular shaped roof finished with capstones. Charcoal remnants on the floor in front of the sealed chamber indicated that rituals had been performed there. The archeological team, working on a project to maintain Mexico’s cultural heritage, was under the auspices of INAH, the National Institute of Anthropology and History. They all sensed this was an important discovery. Temple XIII abuts the Temple of the Inscriptions, Palenque’s tallest pyramid and the burial monument of its famous ruler K’inich Janaab Pakal. In 1942, Pakal’s tomb had been excavated by Alberto Ruz Lhuillier, revealing the first royal Mayan burial in a pyramid, compared in its richness of jade, ceramics and jewelry to the tomb of Egypt’s King Tut. The team made a cut above the sealed door, extended a long-neck lamp through and saw inside a closed sarcophagus carved in one single piece and painted red with cinnabar, a mercuric mineral used as a preservative in burials. Two weeks later, after careful preparations, the team carved a

Sarcophagus of Red Queen

larger entrance into the chamber and found many artifacts, including a spindle whorl used for weaving, figurines made into whistles, and ceramic bowls that dated the burial between 600-700 CE. In the early hours of June 1, 1994, the team used the hydraulic lift technique that Ruz had applied to open Pakal’s sarcophagus, slowly cranking the monolithic limestone lid off. A strong odor of cinnabar emanated from the sarcophagus, and the workers had to put on face masks. When the lid was moved aside enough to allow entry into the vault, the team beheld a royal form not seen for fourteen centuries. A skeleton lay on its back, bones completely permeated with red cinnabar. On the skull was a diadem of flat, round jade beads; hundreds of bright green fragments framed the cranium. More jade, pearls, shells and bone needles covered and surrounded the skeleton. They were from necklaces, ear spools, and wristlets that adorned the entombed body. On the chest were many flat jade beads and four obsidian blades; three small limestone axes covered the pelvis. The interior of the sarcophagus was coated with cinnabar. A royal burial had been found. It was the biggest discovery in Mesoamerican archeology in 40 years, making headlines and drawing a visit from the Mexican president. Everyone wanted to know who was buried in Temple XIII. Fanny Lopez had an intuition that it was a woman, a Mayan queen. Three months after the discovery, physical anthropologist Arturo Romano Pacheco was sent by INAH to examine the skeleton. He determined from the shape of the pelvic bones and other skeletal markers that it was a woman. Speculation ran rampant

Mask of Red Queen – Jade and Jadeite

over which Mayan queen was interred next to Pakal: his grandmother Yohl Ik’nal, his mother Sak K’uk, his wife Tz’aakb’u Ahau, or his daughter-in-law K’inuuw Mat. It took many more years to determine this with any certainty. Advances in strontium isotopes and DNA analysis of bones were needed to narrow it down to someone not genetically related to Pakal. Most Mayanists now believe the Red Queen of Temple XIII is Pakal’s wife, Tz’aakb’u Ahau. Since there were no glyphs carved on her sarcophagus or painted on the walls of the tomb, epigraphic confirmation is not available.

The story of Pakal’s wife is brought to life in my historical fiction book:

The Mayan Red Queen: Tz’aakb’u Ahau of Palenque (Book 3, Mists of Palenque Series)

Temple of Inscriptions – Temple XIII – Temple of Skull (c.700)

Temple of Inscriptions – Temple XIII – Temple of Skull (c.2005)

If you read Spanish, I highly recommend Adriana Malvido’s book La Reina Roja. It details the discovery of the Red Queen’s tomb.

August 11, 2015

The Mayan Red Queen is Here!

The Mayan Red Queen: Tz’aakb’u Ahau of Palenque

Mists of Palenque Series – Book 3

Ancient Mayan civilization comes alive in historical fiction

Maya ruins restored to their glory in Palenque (Lakam Ha)

Just published as ebook on Amazon

Book 3 in the series about Mayan Queens

In the third Mayan Queens book, the ancient Mayan city of Lakam Ha (Palenque) has a new young ruler, K’inich Janaab Pakal.

K’inich Janaab Pakal

Ruler of Palenque 615-683 CE

Portrait carved in limestone

His mother and prior ruler, Sak K’uk, carefully selects his wife (the Red Queen) to avoid being displaced in Pakal’s affections. Lalak is a shy and homely young woman from a small city who relates better to animals than people. She is chosen as Pakal’s wife because of her pristine lineage, but also because she is no beauty. Arriving at the main city of the region, Lalak is overwhelmed by its sophisticated, complex society and the expectations of the royal court. Her mother-in-law is critical and hostile, conferring an official name on Lalak that reveals her view of the girl as a breeder of future rulers: Tz’aakb’u Ahau, the Accumulator of Lords who sets in place the royal succession. Lalak struggles to learn her new role and prove her worth; soon discovering that she also must fight to win Pakal’s love. He is still smitten with a beautiful woman who has

Tz’aakb’u Ahau

The Red Queen

Wife of Pakal, called Lalak in this story

been banished from the city by his mother. Simmering conflict and tragic losses besiege their relationship, until Lalak is compelled to claim her rightful place. She envisions how she can play a pivotal role in Pakal’s mission to restore the spiritual portal to the Gods that had been destroyed in a devastating attack. Through learning sexual alchemy, Lalak brings the immense creative force of sacred union to give rebirth to the portal. But first, Pakal must come to view his wife in a new light.

Modern archeologist Francesca, ten years after discovery of the Red Queen’s tomb, continues her research on the mysterious crimson skeleton found in a temple adjacent to Pakal’s burial pyramid at Palenque. She teams up with British linguist Charlie to decipher an ancient manuscript left by her Mayan grandmother. It gives clues about family secrets that impel them to explore what a remote Mayan village can reveal.

I’ve been working on this book for over one year. It’s really gratifying to have it published,

Leonide Martin

Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico

since I think it may be the best yet in the series. But, how can a “mom” give preference to one “child?” In truth, I love them all and believe they tell rich and compelling stories about these powerful Mayan women who shaped their people’s destinies. Very few except Maya experts

know about them, so I’m hoping that my books bring them to the attention of a wider readership. Of the four “queens” in this series, two were rulers in their own right, and two were the wives of rulers. They were all in the lineage of K’inich Janaab Pakal, the most famous of Maya rulers whose incredibly rich tomb has been compared to that of Egypt’s King Tut. — Leonide Martin

Lakam Ha (Palenque) as it appeared in 650-750 CE

Original source National Geographic

I hope you will read The Mayan Red Queen. It will take you deeply into the world of the ancient Mayas during the height of their civilization, set in the most mysterious and beautiful city of the Classic Period. You will meet fascinating historical figures and follow the unfolding of actual events as Pakal’s dynasty spreads influence in its region and his city gains widespread acclaim as a vortex of artistic expression. You’ll be intrigued by the workings of Mayan shamanism and Lalak’s mastery of sexual alchemy to raise the Jeweled Sky Tree (the sacred portal). And, you’ll experience elegant high court protocol, esoteric Mayan calendar ceremonies, harrowing Underground encounters with Death Lords, and an exquisite love story of the most powerful royal couple in the Americas.

Special introductory price $1.99 until August 20th (normal price $5.99)

Historical fiction fans will also enjoy the first two books of the series, about the grandmother and mother of Pakal. Each story stands alone, but you gain additional richness when you read them in succession.

The Visionary Mayan Queen: Yohl Ik’nal of Palenque – Book 1

The Controversial Mayan Queen: Sak K’uk of Palenque – Book 2

May 14, 2015

El Mirador Adventure

La Danta complex at El Mirador

Most Maya enthusiasts harbor the desire to visit El Mirador, a Pre-Classic site in northern Guatemala. Few ever do it, however, because getting there is arduous. El Mirador is located in the heart of a large swath of undisturbed low-lying jungle called the Mirador Basin in the Mirador-Río Azul National Park. This large tract of sub-tropical jungle is full of bajos or low wetlands with surrounding marshes, and no roads give access to its interior. The nearest town, Carmelita, sits at the end of a long dirt road. It takes three days of travel on narrow paths by foot or mule to reach the site, braving rains, mud, mosquitoes, snakes and jaguars. Most visitors come by helicopter, a thirty-minute flight from the town of Flores on Lake Petén Itza. This remote region is within the Maya Biosphere Reserve, 8100 square miles of protected rain forests designated by the Guatemalan government and supported by many groups to prevent deforestation, destruction and looting of ancient Maya sites.

Prudently, our group of ten intrepid Maya enthusiasts opted for helicopters over mule train. Led by Dr. Edwin Barnhart of the Maya Exploration Center, we flew over the rolling canopy of trees including

Helicopters landing in small clearing

ramón (breadnut), ceiba, mahogany, copal and sapodilla, some growing to 150 feet. Once beyond the reserve edge, cleared fields used for crops and cattle gave way to an unbroken sea of dense foliage, punctuated by what seemed to be hills, but were the tree-covered peaks of ancient pyramids. When we reached the tallest pyramids, whose stone tops protruded beyond the canopy, the helicopters circled for landings at the sites we were visiting: Nakbe, El Mirador and El Tintal. With military precision, the pilots hovered over small clearings nearly undetectable until you were right over them, and settled the helicopters down.

For most of us, this was the trip of a lifetime. All students of the ancient Mayas, we knew El Mirador was among the oldest Maya cities, possibly the largest, often called the “Cradle of Maya Civilization.” Although abandoned over 2000 years ago, there are tantalizing hints that the people of El Mirador may have migrated to the Caribbean coast then back inland to settle at Kalakmul, a powerful rival to Tikal in the sixth and seventh centuries. Mirador was known as the “Kan Kingdom” in the Pre-Classic, and the rulers of Kalakmul said they were Lords of Kan.

The Mirador Basin was home to numerous Pre-Classic Maya cities that might have supported a population close to a million people.(1) The oldest city, Nakbe, was likely occupied before 800 BCE, with clear evidence of occupation by 600 BCE. El Mirador, the largest city, flourished between 300 BCE and

Map of El Mirador

150 CE with a peak population over 100,000. Its central area covers 10 square miles with several thousand structures, and its pyramids reach 180-230 feet high and include “La Danta,” among the largest pyramids in the world with its total volume of 99 million cubic feet. The second largest city, El Tintal, was occupied during this same time period. Its central area covers 3.5 square miles with nearly 1000 structures and several pyramids, the tallest 160 feet.

These three cities were linked by raised roadways called “sacbeob” built of stone and plaster, creating a network of white causeways through the jungle. Within each city, sacbeob led from one complex to another, providing a level walkway rising 18-20 feet above ground level and some 60-150 feet wide. The remnants of these causeways still provide level walking surfaces, now traversed by tree roots but cleared of brush by site workers.

The primary archeological work in Mirador Basin is conducted by Dr. Richard Hansen of Idaho State University. Beginning in 2003, his team initiated investigation, stabilization and conservation programs with a multi-disciplinary approach involving 52 universities and research institutes. The ruined city had been recorded and photographed in 1926-1930, but its remote and inaccessible location deterred much investigation, with Ian Graham making the first map in 1962 and Ray Matheny excavating the site center in the 1980s. The archeologists were surprised to find construction that was not contemporary with the

Pottery found at El Mirador

large Classic cities in the area, such as Tikal and Uaxactun, but from earlier centuries. Pottery fragments collected by Joyce Marcus in 1970 and others found by Richard Hansen in 1979 were identified as Chicanel style, a monochrome red, black or cream with turned-out rims and a waxy feel. This pottery had been dated to Late Pre-Classic (300 BCE – 150 CE).

Finding complex cities with immense platforms, tall pyramids and royal compounds that were dated to Pre-Classic times caused a shift in thinking about Maya civilization. The Mayas had a high culture and sophisticated social structure far earlier than was previously believed. Speculation about the source of Maya kingship systems that produced such monumental architecture include diffusion from Zoque-Olmec centers such as La Venta and Chiapa de Corzo, as well as cultural interaction with other Maya centers to the west. Multiple opportunities for cultural borrowing and lending raise the question of who borrowed what from whom.(2)

Walking on sacbe at El Mirador with archeologist Ed Barnhart (red shirt)

Sunset from top of El Tigre pyramid

As our group walked the wide tree-shrouded paths, we saw tall mounds of tumbling rocks rising through the foliage, and were amazed at the size and number of structures. Several complexes in El Mirador were partially cleared and restored, giving provocative views into this ancient culture that left no writing yet discovered. A central complex held several tall pyramids including El Tigre and its two flanking pyramids forming a triad group, with the Monos and Leon pyramids farther away. We climbed rickety stairs to the stony top of El Tigre and watched a spectacular tropical sunset. A five-mile round trip trek from our camp brought us to La Danta, gradually ascending over several levels of plazas covering nearly 45 acres. The platform supporting La Danta is 980 feet wide and 2000 feet long. Although the actual pyramid summit did not seem dauntingly tall once we arrived at its final platform, we kept

La Danta complex superimposed on Tikal Acropolis

remembering all the previous levels we had ascended. La Danta stands 230 feet, taller than Temple IV at Tikal. Though not as tall as the Great Pyramid of Khufu in Egypt, it is larger in volume at 99 million cubic feet.

Climbing switchback wooden stairs with handrails, we ascended to the top of La Danta and gazed across miles of jungle stretching 360 degrees to all horizons. A light wind cooled our over-heated bodies as we rested thankfully on large square stones. Two geodesic markers gave coordinates for the summit. In the distance the mounds of Nakbe and La Tintal were visible as forested hills. It was heady to be standing atop the reputed largest pyramid in the world. A sense of the expanse and inter-connectedness of the ancient Maya world created feelings of awe.

Stairs to La Danta platform

La Danta summit view across jungle

Standing on La Danta summit

The most important artwork found at El Mirador is the Central Acropolis frieze. In 2009 a student named J. Craig Argyle uncovered two 26-foot carved stucco panels that had been covered over by another structure. Their burial inside this structure, filled with dirt and crumbled stone, preserved this beautiful creation that depicts two young men in the “swimming god” posture. Above them are two bird figures, one a cormorant and the other a human-faced macaw. Richard Hansen believes the frieze relates Popol Vuh mythology, showing the Hero Twins, one wearing the jaguar headdress containing the head of his father. The Twins descended into Xibalba, the Underworld, to defeat the Death Lords and resurrect their father (Hun Hunahpu, First Father of the Mayas). The cormorant signifies rulership lineages and links to Great Mother Goddess Muwaan Mat (Duck-Hawk/Cormorant). The human-faced macaw represents the False Pole Star Wuqub Kaquix, an arrogant macaw who tried to become a god. The Hero Twins shot him from a tree with their blow-gun, unseating his lordship.(3)

Central Acropolis Frieze

Composite View

Finding this depiction of the Popol Vuh myth in a Pre-Classic site proves that the story has great antiquity and predates contact with Spanish Christianity by thousands of years. Contact-era renditions of the Popol Vuh were thought to be influenced by Christian imagery. Ed Barnhart questions whether the frieze actually depicts the Popol Vuh, because key elements that signify the Hero Twins, such as jaguar spots and catfish barbels, are missing. However, we know the Popol Vuh was well-established early in Maya mythology from murals discovered in San Bartolo, Guatemala, dated to 100 CE that also portray scenes from this story.(4)

Tent camp rigors

To see these fantastic carvings and other artifacts, to climb the pyramids that soared above the jungle canopy, to walk the pathways trod by ancient Mayan feet in times long past, required commitment and dedication. Conditions in our tent camp in El Mirador were primitive, without electricity or running water, and without showers. Our guide Ed Barnhart arranged for everything we needed to be brought by

Ocellated turkey

mule train, a 5-hour trek along a jungle path from Carmelita. The mules packed in all our drinking and cooking water, food, drinks, tents, bedding and implements. A staff of two cooks, two local guides, and four carriers attended us. Our meals were surprisingly good, cooked over fires in primitive conditions. The Mayan woman cook made delicious traditional tortillas and provided meals of rice, chicken, vegetables, black beans, eggs, pancakes, fruit and cereal. We drank from water bottles, using iodine to purify the larger water tanks when we ran out of bottles. Refreshing limeade accompanied meals; at

Camp hand washing station

times we resorted to luke-warm gatorade when the ice melted. A hand washing station with suspended dishrag and soap dispenser served well; we had several tarp-enclosed outhouses and a tarp-covered picnic table. In our tent area, three hammocks suspended from trees offered afternoon respite.

Hammocks and tent camp

Unseasonal rains occurred before we arrived, so the first day was fresh and less hot. Hot is the operative word; the next several days were roasting and muggy. Everyone got very sweaty, especially as we wore long sleeve shirts and long pants with closed shoes to prevent bites. There were far fewer bugs than expected; our guides said “three mosquitoes per person” but an abundance of spiders, gnats, moths, ants, and crickets. Very large, black cicadas serenaded us dusk and dawn, making an ear-splitting high whine. A flock of ocellated turkeys hung around camp, their iridescent feathers shining. The male’s deep popping noises started at 4:00 am, along with the roars of howler monkeys that are often mistaken for jaguars, which actually make grunting noises. Though some folks were concerned about the deadly fer-de-lance snake (called yellow jaw) our guides said rattlesnakes are much more common. The only snake we saw was a small dead one, possibly a fer-de-lance.

Sleeping in tents on air or foam mattresses was far from comfortable, especially the last two nights that were oppressively hot. A generator provided light until 9:00 pm at the kitchen and meal area, and around our tent camp hammocks. Trips to the outhouse required using flashlights and keeping an eye out for snakes and bugs. We were up at dawn, thanks to the turkey and howlers, and eager for our first

About to climb Nakbe pyramid

cup of coffee – surprisingly good instant called “Inka-mundo.” Taking advantage of the morning for our first excursion, we hit the sacbeob early and were out around 2-3 hours, using lots of energy walking and climbing. We’d return for lunch and a siesta, then make another trip to the site late afternoon. At Nakbe and El Tintal, we spent about 2 hours while the helicopters waited. Upon returning to Flores, the first thing everyone did was take a long shower, do some email or texting, then get a cold margarita or beer!

Back in Flores enjoying margaritas

Our group of adventurous souls was uncomplaining about creature discomforts and deeply appreciative of this great opportunity to visit a remote Maya site of vast significance. The impressive size and number of cities with their monumental and residential structures, located in a nutrient-rich swampy region, led our imaginations to picture the area at its height: people streaming along wide sacbeob, using sophisticated techniques to quarry huge limestone blocks without metal tools, move them to building sites without wheels and lift them to amazing heights, interacting in complex class societies with a cohesive ideology, performing splendid rituals, producing striking carved art and ceramics, collecting rainwater in cisterns, using body decoration such as inlaid jade in teeth and skull shaping, and using imported objects such as seashells, obsidian and basalt.

Between 100-200 CE, the cities of Mirador Basin were abandoned. The people apparently left quickly,

Drawing of Nakbe platform

leaving ceramics and working tools where they were used. Hansen believes the exodus was caused by destruction of the swamps that supported their agriculture. Massive deforestation in surrounding areas to provide wood for making lime plaster may be the underlying cause. In El Mirador they plastered everything from temples and plazas to sacbeob and house floors, making the plaster thicker over time. The reason, says Hansen, was “conspicuous consumption” by elites trying to sustain an image of wealth and progress. Clay drained from forests into the swamps and covered the rich soil. A portion of El Mirador was temporarily re-occupied in the Late Classic, around 700-900 CE, with small structures built among the ruins. Here the occupants, probably scribes

Maya Codex style ceramic

and artists from Kalakmul, produced unique “Codex-style” ceramics, fine polychrome ceramic consisting of black line drawings on a cream colored background. This was beyond doubt the trip of a lifetime. It was not easy, but it was rich in learning and experiencing

Ed Barnahrt and Lennie Martin, La Danta summit

the residuals of a once-great culture that flourished then declined, leaving many unanswered questions. For Maya enthusiasts, it stimulates further research into the mysteries of the Pre-Classic, seeking to understand how kingship structures and class societies came into being, the power and trade relationships among sites, the stories of the residents and their lives.

References

Chip Brown. El Mirador, the Lost City of the Maya. Smithsonian Magazine, May 2011.

John E. Clark and Richard D. Hansen. The Architecture of Early Kingship: Comparative Perspectives on the Origins of the Maya Royal Court. Royal Courts of the Ancient Maya, Vol. 2. Edited by Takeshi Inomata and Stephen D. Houston. Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 2001.

Dennis Tedlock. Popol Vuh. Touchstone Book, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996.

William A. Saturno, David Stuart, Boris Beltrán. Early Maya Writing at San Bartolo, Guatemala. Sciencexpress Report, January 5, 2006.

Leonide (Lennie) Martin writes historical fiction about ancient Mayan civilization. Visit website at Mists of Palenque.

March 24, 2015

The Palenque Beau Relief: A Maya Beauty Vanishes

Palace at Palenque

Jean-Frederic Waldeck

Among the most beautiful artwork of the ancient Mayas are the carved stone and stucco panels of Palenque.

This city flourished from 400-900 CE in the mountain rain forests of southern Chiapas, Mexico. It became the regional vortex of creativity and the dominant ritual-political center during the reigns of K’inich Janaab Pakal and his sons. Rediscovered in the 16th Century by Spanish explorers and brought to international attention in the mid-1800s by John Lloyd Stephens’ travel books (1,2), Palenque enthralled visitors with its graceful, realistic figures on numerous panels and pillars, its harmonious architecture and copious glyphic writing.

The relief panels were carved of high quality limestone and coated with layers of stucco, creating smooth surfaces. Originally these were painted vibrant red, green, yellow and blue but the colors faded over the centuries. Many buildings had panels set into the walls of chambers and figures adorning pillars, including the Palace, Temple of the Inscriptions, and Cross Group. Panels set inside the interior chambers of buildings were best preserved; many pillar carvings deteriorated over time due to the humid tropical climate and encroaching vegetation.

The Most Beautiful Panel

In a small temple just west of the Otolum River, not far from the Cross Group, once resided “the most

The Beau Relief

Jean-Frederic Waldeck

beautiful piece of art of the aboriginal Indians,” said Paul Caras in his 1899 article published in The Open Court journal, Volume 13. It was a panel depicting a single male figure dressed simply, seated on a double-headed jaguar throne. This panel is known as the Beau Relief for its beauty. The elegant position of the figure’s arms and legs evoked a languorous dance. Rows of hieroglyphs bordered the upper sides and the throne was set upon two powerful claw-like legs. The panel was set on the inner chamber’s rear wall in the small, nearly square temple that sat on top of a hill. Steep stairs climbed to the entry chamber where a single front doorway gave access; its rear door led to the inner chamber. An opening in the floor of the inner chamber led to stairs that descended into a basement chamber.

The first European to depict the Beau Relief panel in this jungle-shrouded temple was Ignacio Armendáriz, an artist who accompanied Antonio del Río, artillery captain serving in the Spanish outpost in what is now Guatemala. By order of King Charles III of Spain, the ruined cities in the jungles of his new territories were to be explored and documented. In 1787 the Spaniards climbed the steep, treacherous trail following river cascades up to the ruins of Palenque, led by local Ch’ol Maya guides. After a month of clearing off trees and shrubs, the group exposed several impressive stone buildings. Del Río dug for artifacts and collected some art objects, while writing descriptions of Palenque’s buildings. Armendáriz drew pictures of 30 subjects, including tablets of the Temples of the Sun, the Cross and Foliated Cross, hieroglyphic tablets from the Palace subterranean passageways, and the Beau Relief tablet in the Temple of the Jaguar.

Considering the adverse conditions Armendáriz faced, his work is remarkable. He suffered debilitating

The Beau Relief

Ignacio Armendariz

heat of tropical spring, working in half-lit interiors of sweltering chambers, drawing on damp paper soaked with humidity and perspiration, trying to capture complex details of images completely alien to him. In comparison to modern renditions, his drawings seem stilted and inaccurate in many details. But, they captured the essence of a strange and unknown culture. His is one of only two original drawings of the Beau Relief and is historically very significant. It was copied by José Castañeda two decades later and appeared in books published in early-mid 1800s. (3, 4, 5)

The second artist to draw the Beau Relief was the flamboyant Jean-Frederic Waldeck, a self-proclaimed count with a colorful and controversial history. Waldeck resided at Palenque for about one year in 1832, and carefully drew the panel on a grid, adding embellishments such as fine-line suggestions of musculature and costume details that gave a classic Roman look. Waldeck intended his work for popular consumption and believed the amazing ruined cities were created by ancient Asian or European cultures, or reflected cross-cultural stimulation. Shortly after Waldeck completed this drawing, the upper portion of the Beau Relief was destroyed, leaving only the throne and its legs. It is not clear how this occurred; some Mayanists believe Waldeck caused the figure’s destruction for unknown reasons. (6) During this time period, looting artifacts from ruins was common, including removal of portions from wall panels and pillars.

Temple of the Jaguar

Ruins in Palenque Jungle

Temple of the Jaguar

Drawing shows Beau Relief panel in rear chamber

Now the Temple of the Jaguar is a partially collapsed ruin sitting on top a high hill, infrequently visited because of the steep path through dense jungles leading to it. We can only imagine what this magnificent sculpture in stone and stucco – the Beau Relief – must have looked like when freshly created, possibly portraying Pakal in his glory as the greatest ruler of Palenque.

Stephens, John Lloyd (1841) Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan. Two volumes, Harper and Brothers, New York.

Stephens, John Lloyd (1843) Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan. Two volumes, Harper and Brothers, New York.

Humboldt, Alexander de (1810) Vues des cordilléres en monuments des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique. Chez F. Schoell, Paris.

Del Río, Antonio, and Paul Felix Cabrera (1822) Description of the Ruins of an Ancient City… Henry Berthoud, London.

Kingsborough, Lord (1829-1848) Antiquities of Mexico… Nine Volumes, London.

Stuart, David and George Stuart (2008) Palenque: Eternal City of the Maya. Thames & Hudson Ltd, London.

January 28, 2015

Mayan Academy of Ancient Astronomy

Xultun Astronomers

Xultun, Guatemala

Ancient Maya Astronomic Workshop

In the steamy jungles of Guatemala, a team of archeologists led by Boston University’s William Saturno returned in 2011 to a little known site named Xultun. The site has been dated to the 9th century. A member of the team, Max Chamberlain, had been working on a modest building within a residential area that had a large looter’s trench dug through its middle. In March 2010 Max saw the remnants of a wall mural on the west wall of this building, exposed by the looter’s trench. Maya ruins at Xultun were first reported in 1915, and expeditions went in the 1920s and again in the 1970s to map the site’s monuments. These expeditions did not find much except crumbling structures, and over the years looters repeatedly raided the site for artifacts. Saturno’s team in 2010-2011 was not expecting to find much left, especially not wall murals.

Looter’s trench into building rubble with exposed mural inside

Max’s building was certainly not one where archeologists anticipated finding wall murals. It was close to the surface rather than deep inside a building complex. Murals are delicate and do not last in the humid lowlands climate. The room was a small structure, six and a half feet wide by six feet long, with a 10 foot tall vaulted roof. The ancient Mayas modified it over several construction phases, the most recent one filled the room with rubble and earth and the final phase was built over it. One remarkable thing was that the Mayas filled in the room through the doorway, rather than collapsing the roof to fill its interior so they could build over the top of it. This method served to preserve the murals inside quite well. The looters carved their trench into the room looking for a tomb, which they did not find. They abandoned their search, leaving a portion of the west wall paintings exposed to weather. It was this faint and barely perceptible mural that Max Chamberlain saw.

William Saturno gets a look at wall mural inside Xultun building

A surprised William Saturno confirmed that Max was indeed seeing murals. The team continued excavating and during 2011 they cleared out the debris to reveal that three interior walls and the ceiling were covered by murals. The state of preservation varied, depending on how close the murals were to the exterior surface. Looking through the doorway into the room, you see a series of life-size figures seated on the west wall. Their bodies are painted black and they all wear the exact same costume, a white loincloth and a large black “bishop’s miter” hat with a single red feather on the top. These three figures look upward and towards the north wall. On the north wall is another figure painted in orange. He has a more elaborate costume with headdress and jade wristlets. His hand is outstretched holding a stylus, pointing towards another seated figure, the ruler of Xultun.

Xultun mural with one black-colored astronomer and ruler’s scribe

In the center of the room is a stone bench where the ancient Maya would sit. All the east wall and part of the north wall is covered with numerous small, delicately drawn hieroglyphs of various sizes painted in black and red. These glyphs and bar-and-dot numbers arranged in vertical columns resemble the astronomical charts and ephemeral calendars seen in the Dresden Codex, an ancient Maya screen-fold manuscript originally written in the 11th to 12th century. At the top of these columns are moon glyphs combined with lunar deity heads, followed by columns of three numbers that record elapsed days using periods of the Long Count calendar. Analysis of the numbers showed they calculated lunar semesters, a way the Mayas tracked lunar cycles and predicted eclipses. A set of 27 columns of these lunar tables span across the wall.

Lunar series glyphs with dot-and-bar numbers

To the left of the lunar series, incised thinly over a painted mural figure, is a “ring number.” The only other place ring numbers appear is in the Dresden Codex. This is a count of days with the lowest number circled, making a ring around the number. The lowest number would be the day (kin), indicating how many days to subtract from the current Maya cycle start date of August 11, 3114 BCE. To the Mayas this date is 13.0.0.0.0 4 Ahaw 8 Kumk’u. It is not clear how the Xultun astronomers were using ring numbers, but these can be linked to lunar cycles.

On the north wall is a group of four columns painted in red with very large numbers, beginning with a Tzolk’in day followed by a vertical line of five numbers that are some form of Long Count calculation. The time spans express a wide range of accumulated time, some small and others extremely

Long Count style numbers in columns

large. Similar lengthy tallies of days appear as Distance Numbers in the Dresden Codex and on carved monuments. It is possible these tables serve astronomical ends, since they are divisible by 52 (Calendar Round) and 260 (Tzolk’in Calendar). One column contains day numbers that are even multiples of 584, the Maya calculation for the cycle of Venus. Another has numbers evenly divisible by the Maya 819-day cycle related to synodic periods of Jupiter and Saturn. These Long Count style calculations take you back in time as far as 3207 BCE and as far into the future as 3136 CE.

The small building with murals in Xultun appears to be as astronomer’s workshop. The walls were covered with repeated layers of stucco, and the surface upon which the murals are seen is the final layer with many others underneath. This probably served as an astronomer’s blackboard, but instead of erasing their calculations they applied another layer of stucco to make a new surface. The hieroglyphic texts now on the walls at Xultun express dates specifically for 813 or 814 CE. These texts were likely copied and recopied over many generations and

Reconstruction of Xultun astronomer’s building

updated periodically from observational data of eclipses, lunar and planetary cycles. The Xultun murals are the earliest example yet found of such Maya astronomical calculations.

Did Saturno and Chamberlain discover a Classic Period ancient Mayan astronomical academy? Because of the small building’s characteristics, it might have been part of a residence for astronomers. You can imagine them gathered in the room, perched on the stone bench and painting their intricate glyphs and numeric calculations with black and red plant dyes on the fresh stucco wall. One man dressed more elaborately, perhaps the ruler’s scribe, poises his stylus waiting the ruler’s words. The ruler in trance, channeling a Maya deity, reveals mystical understandings of sacred calendric cycles that the astronomers will use in making their calculations.

Xultun mural reconstruction seated ruler

Xultun mural reconstruction of kneeling scribe

October 24, 2014

Mayan Mystic Codes

Mayan Hieroglyphs on Ceramic Cup

Secrets of Mayan Glyphs

The ancient Mayas had a complex system of writing using intricate hieroglyphs carved in stone or drawn with quill pens on bark-paper books called “codices.” They also painted beautiful scenes on ceramic pottery with glyphs identifying the owner and who appeared in the drawings. Symbols used in glyphs include geometric shapes, vegetal and animal motifs, human figures and fantastic composite creatures. Each symbol held deep spiritual meaning for the Mayas; most of these concepts are beyond understanding using rational western thinking. Many exquisite panels full of glyphs and carved figures were placed on interior walls of temples built on top of tall pyramids. Only initiated priests and elite nobles could enter and view these panels. Reading the glyphs was done using rituals that created altered states of consciousness. It was essential to enter sacred space and enhanced consciousness to understand the mysteries written in the glyphs.

Mayan tradition maintained by elders such as Hunbatz Men, Itza Maya Daykeeper-Shaman, tells that the Mayan language was

Itzamna Painted on Vase

brought to the people by the god Itzamna. Itzamna was an important deity who taught sacred writing, a sky god who opened a portal to bring itz into the world. His name means “one who does itz” and he brings the people this sacred substance, liquids or sticky things permeated with the essence of the divine. He is the original shaman and ultimate teacher of humanity. The language he taught the Mayas came from the sounds of the cosmos and the natural world, and reflected the laws of the universe. These words could be read from left to right and from right to left; a process called Zuyua. Only those initiated into high levels of Maya religion knew how to read using Zuyua.

Mayan words are mantras and saying the word activates the energy possessed by the sound. The vibratory sounds of Mayan words have the power to set energies into motion and bring things into manifestation. They are bija sounds like ancient Indian Sanskrit. To activate the energy enclosed in the sounds, one must be spiritually

Maya Pyramid Pose K’u showing kundalini energy

advanced and master disciplines to control functions of the language. Along with these mantra sounds, the Mayas used hand gestures (similar to Hindu mudras) and postures (similar to Hindu asanas) to add further power.

This example of Zuyua taught by Hunbatz Men shows further similarities to Sanskrit. The Mayas knew about energy pathways

Hunbatz Men, Itza Maya Daykeeper-Shaman

through the body, such as kundalini that travels up the spine. One word they used for this was k’ultanlilni. This word spoken from left to right means:

k’u – god, pyramid; l – vibration; tan – place; lil – vibration; ni – nose. K’ul also means coccyx. The composite meaning reads: “The coccyx as the place of vibration is directly related to the nose because it is where the breath of the Sun God enters.”

Reading the word reversed, in lil nat luk’ the meaning is amplified:

luk’ – to take swallows in small doses; nat - mount or secure into place; lil - vibration; in – personal pronoun “I.” The composite meaning reads: “Take in (swallow) divine energy/god in small doses and secure it by absorbing it into consciousness, these vibrations are retained and become me (I).”

Hunbatz Men. Secrets of Mayan Science/Religion. Bear & Company, Santa Fe, NM 1990.

Lennie's Blog

- Leonide Martin's profile

- 142 followers