Leonide Martin's Blog: Lennie's Blog, page 4

December 8, 2016

Solstice, Equinox, and the Mayan Calendar

Mayan Sun God — K’inich Ahau

The movements of the sun were particularly important to the ancient Mayas.

The sun god, represented as the K’in glyph in Classic times, had a Roman nose, central notched tooth, and crossed eyes with square pupils. Considered a male deity and addressed as Father Sun, he was ruler of time and space, and oversaw the seasonal agricultural cycles. K’inich Ahau—Sun-Faced Lord—was identified with ruling lineages and connected with the Maize God, bringer of fertility and renewal. In the late Classic many Maya rulers added K’inich to their names, signifying their oneness with the sun deity. To demonstrate this unity, rulers needed astronomical knowledge to predict exact timing of the sun’s annual cycle. Through this they directed farmers when planting and harvesting should take place. The sun’s arrival at important stations during the year was celebrated with rituals, and correct timing was essential. The ruler’s sacred duty required properly performing these rituals, offering the deities suitable gifts, and thus maintaining beneficent relations between Gods and humans.

Glyph of Sun God

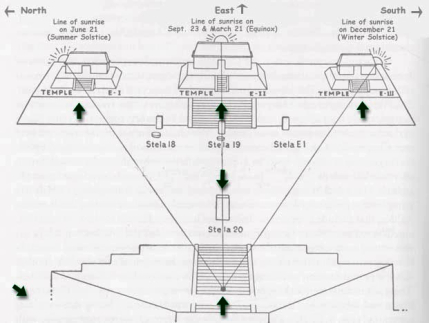

This relationship with time and the cosmos was expressed by the movements of the sun. Divine rulers depended on their astronomical knowledge to predict the solstice, equinox, zenith and nadir passages of the sun. They needed markers to help identify when the sun approached these stations, and to signal the exact moment of arrival. In the Early Classic Maya period, solar-oriented structures called “Group E” complexes appeared throughout the Maya area. These complexes usually had four buildings: three modest height pyramids in a string along the eastern horizon, and a single temple standing directly west of them that was used for sighting. From the sighting temple, observers would watch for the rising sun behind the north pyramid for summer solstice, the middle pyramid for the equinoxes, and the south pyramid for winter solstice.

Group E Complex

Uaxactun

Maya architecture was developed to encode ancient astronomical knowledge and serve as a focus for sacred rituals. Structures were built and sited in positions that would align with the sun’s movements and produce solar-related phenomena. These structures could be witnessed by multitudes and were used to perform dramatic ceremonies. Among the best known examples, two are located in Yucatán, Mexico.

Equinox Sunrise at Dzibilchaltun

At Dzibilchaltun located just north of Mérida, Yucatán, a famous equinox phenomenon draws thousands of visitors every March 21 and September 21. A square shaped, small temple called “The Temple of the Seven Dolls” sits on top of a 2-tiered 4-sided platform that is oriented east-west. Doorways on four sides of the temple give unobstructed view through its interior. From the west, a long causeway leads to the structure, beginning from viewing platforms at the edge of the main portion of the city. People gather in the pre-dawn to stand on the platforms or along the causeway, waiting hushed moments as the eastern sky slowly brightens. As the sun breaks the horizon, it seems to rise from within the temple, its blazing globe filling the east-west doorways. The sun continues upward and appears to burst forth from the flat roof of the temple. As in ancient times, modern Maya elders conduct solar rituals with their followers to honor the sun’s power and abundant energies.

Descent of the Feathered Serpent, Chichen Itza, Pyramid of Kukulkan

The large Postclassic site Chichén Itzá is south of Mérida, has been named a New 7 Wonders of the World; possibly the best known ancient Maya city. A striking solar phenomenon takes place on the equinoxes called the “Descent of the Feathered Serpent” that is a national holiday, attended by hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and foreign visitors. The largest pyramid in the site, the Pyramid of Kukulkan (called El Castillo by early explorers) sits in the vast central plaza. This four-sided pyramid has stairs ascending each side and a square temple on top with prominent serpent pillars and carvings. As the equinox sun begins to set, its light plays across seven of the nine tiers of the pyramid and casts triangular shadows on the stairway on the east side. The entire length of the stone balustrade along these stairs is carved as a feathered serpent. The serpent’s head rests on the ground, jaws open wide with protruding fangs and tongue. Its tail reaches upward from the temple platform on top, rattles pointed to the cosmos. The changing size of the triangular shadows makes the serpent seem to be moving down the pyramid.

Other solar and calendar phenomena are encoded in the Pyramid of Kukulkan. At the solstices, half of the pyramid appears in light and the other half is in darkness. The four sides of the pyramid indicate seasons of the year, and the 91 steps of each stairway combine to make 364 plus the upper platform to represent the solar year, 365 days. The rectangular temple on top has 20 roof projections for the 20 days of the Maya month. The nine tiers viewed from any one side, split by the stairway, represent the 18 months of the Mayan year. Along the lowest tier there are 26 marks on each side of the stairway; these together make 52 for the years in the Tunben K’ak calendar, a time period for “New Fire” ceremonies that follows the Pleiadian cycle.

Winter Solstice Sunset over Pyramid of Inscriptions, Palenque

In the Classic city of Palenque, more complex types of solar phenomena were coded into architecture of complexes. These structures served both ritual purposes and carried symbolic functions, many intended for only rulers and elite. One of the first identified was the setting sun at winter solstice, which sets over the ridge directly behind the Temple of the Inscriptions. This temple is the burial monument of K’inich Janaab Pakal, Palenque’s greatest ruler. Archeologist Linda Schele interpreted this as the “dying” sun appearing to enter the earth through Pakal’s royal tomb; a solar event that was an annual re-enactment of the ruler’s descent into the underworld.

Another solar event occurs at sunset during summer solstice. Sunlight enters the western window of the anterior corridor of the Temple of the Inscriptions, passes through the eastern window directly across the corridor, and then highlights the upper platform of the Temple of the Cross. Once a major stela (rare at Palenque) stood on this spot; researchers suggest that Stela 1 was a portrait of Pakal or his son Kan Bahlam, and marked a solar observation point. The Temple of the Inscriptions has a longitudinal orientation to the summer solstice, and is remarkably aligned to the Temple of the Cross. Schele believed that the light effects of summer solstice represented the transfer of royal power from Pakal to Kan Bahlam, who built the Cross Group and completed his father’s burial temple.

The Cross Group was composed of three major pyramid-temples and two minor ones. It was Kan Bahlam’s ultimate creative expression, which proclaimed Palenque as the reflection of the center of the universe. The three temples represented the three hearthstones of Maya creation mythology, stars in the Orion cluster. In each Maya home the 3-stone arrangement for cooking reflected the stars in Orion’s belt, the home of the creator Gods. This hearthstone arrangement is still used in traditional Maya families.

The Cross Group Solar Phenomena, Palenque

There are numerous solar, lunar, and stellar associations within the structures of The Cross Group, consisting of the Temple of the Cross, Temple of the Foliated Cross, and Temple of the Sun. Solstice, equinox, zenith, and nadir light phenomena are encoded in these structures. Only one is included here: The summer solstice event. On the morning of June 21, at 7:00 am, the sun when viewed from inside the Temple of the Sun rises from its north-most point on the horizon, and touches the northwest corner of the Temple of the Cross.

Summer Solstice sunrise behind Temple of the Cross, Palenque

Sunlight then enters the Temple of the Sun at an oblique angle (50 degrees north of the transverse axis). This diagonal streak of light entering through the northeast doorway continues to creep across the temple floor. As it probes into the dark interior, a broad ray appears. This ray of light gets narrower as it is blocked by consecutive walls, until it becomes a thin beam that strikes the corner of the southwest chamber. By 7:30 am the rays recede from the temple interior.

This solstice alignment was intentional, for the Mayas aligned the temple precisely. They set the northeast corner back 10 cm. from the rest of the facade, to allow the sun to penetrate the interior at the correct angle. The interior walls were constructed to focus the sunrays. Openings were made in walls A and B to permit sunrays to shine through, while wall C has no openings. The doorways had to be perfectly spaced.

Summer Solstice Sunrays entering Temple of the Sun, Palenque

A high level of astrological knowledge was necessary for this construction. The diagonal of the temple (66 degrees 14 minutes) is only one degree off the true azimuth for summer solstice sunrise (65 degrees 14 minutes). However, it is the visible light entering the temple at 70 degrees that creates the light effect. Knowledge of these relationships was needed prior to construction of the temple. Only the elite would observe sunrays deep inside the temple, but the diagonal light entering the northeast doorway could be seen by crowds gathered in the plaza between the Cross Group temples. Another dramatic effect took place when a person standing directly in the center of the temple became fully illuminated by dazzling sunrays, in view of the plaza crowd. One can imagine that Kan Bahlam stood there to reaffirm his personification of the Sun God and inheritor of the Palenque dynasty.

Insert of Kan Bahlam from Temple of the Sun Tablet, standing in sunray

A final light phenomenon occurs on the evening of summer solstice, at 6:18 pm. Standing by a small altar stone near the base of the Temple of the Cross stairway, observers can watch the sun dip past the mountainside behind the Temple of the Inscriptions. The last rays of the sun pierce directly through the center of the Temple of the Sun roofcomb. On the roofcomb a seated figure holds a double-headed serpent surrounded by sky bands. This is a typical portrayal of rulers in command of the cosmos and energies of life and death. He sits upon an Earth Monster mask, representing the mountain behind the Temple of the Sun. A smaller figure on the roof frieze below is Kan Bahlam appearing as the Jester God/God K manikin, symbol of divine royal lineage.

Temple of the Sun

Sunrays shining through roofcomb, Summer Solstice sunset

In multiple ways, the solar phenomena encoded in Maya structures proclaimed the metaphoric and symbolic associations of the ruling elite with the Sun God and cosmic deities. Charged with religious symbolism, the Cross Group embodied the movements of sun and moon, and conveyed a powerful message by the new ruler, Kan Bahlam.

Learn about the early life of K’inich Kan Bahlam in my book telling the story of his mother, The Mayan Red Queen: Tz’aakb’u Ahau of Palenque.

Kan Bahlam’s later life when he ascends to rulership and builds the Cross Group is told in my forthcoming book, The Prophetic Mayan Queen: K’inuuw Mat of Palenque.

Resources

Alonso Mendez, Edwin L. Barnhart, Christopher Powell, and Carol Karasik. “Astronomical Observations from the Temple of the Sun.” 2005. Accessed online 12-6-2010 http://www.observations-temple-sun.pdf.

Hunbatz Men. The 8 Calendars of the Maya. Bear & Company, Rochester, VT, 2010.

Susan Milbrath. Star Gods of the Maya: Astronomy in Art, Folklore, and Calendars. University of Texas Press, Austin, 1999.

David Stuart & George Stuart. Palenque: Eternal City of the Maya. Thames & Hudson, London, 2008.

September 8, 2016

Silver Medal for The Red Queen

Silver Medal Winner of the 2016 Global Ebook Awards

The Mayan Red Queen: Tz’aakb’u Ahau of Palenque receives award in Fiction-Historical Literature-Ancient Worlds.

It was an exciting moment when I received the notice in August that my book won a Silver Medal in the Dan Poynter Global Ebook Awards for 2016!

Book awards mean a lot to authors. They validate our efforts and help bring our books to the  attention of readers and booksellers. The Mayan Red Queen has been given favorable reviews in The Midwest Book Review (2016) and by Writer’s Digest (2016), but this is her first award. So, I am very happy and invite you to share the moment by recalling the story if you’ve read it, or reading the book if not.

attention of readers and booksellers. The Mayan Red Queen has been given favorable reviews in The Midwest Book Review (2016) and by Writer’s Digest (2016), but this is her first award. So, I am very happy and invite you to share the moment by recalling the story if you’ve read it, or reading the book if not.

“The Mayan world and its underlying influences come alive, making for a thriller highly recommended for readers who also enjoy stories of archaeological wonders.” The Midwest Book Review, Diane Donovan, Editor and Senior Reviewer.

“The quality of this novel is top notch . . . beautifully written. The plot was interesting and very unique. The author’s best skill is in crafting believable yet mythical characters that carry the story almost effortlessly. . . fans of complex world building will be absorbed by this one–with pleasure!” Writer’s Digest 3rd Annual Self-Published e-Book Awards

Let me tell you about the historic Mayan woman who became known as “The Red Queen”

Actually, what we know about her is limited. Archeologists discovered her tomb at Palenque in 1994, her skeleton completely permeated by cinnabar, a form of mercuric oxide that leaves a red residue. The Mayas used cinnabar as a preservative, but only for bodies of elite nobles and rulers. Her burial was richly adorned with jade, shells, beads, and artifacts of bone or ceramic, and her face covered by a jadeite mask. They determined that she lived in the mid-seventh century CE, died around age 60, and must have been highly regarded because of her interment inside a large stone sarcophagus.

Mask of Red Queen – Jade and Jadeite

Later research determined that she came from a nearby city and was unrelated to the ruling family of Palenque. When hieroglyphs were deciphered at Palenque, we learned that she was married to the famous ruler K’inich Janaab Pakal in 626 CE, bore him three or four sons, and died in 672 CE. Her memorial pyramid adjoined the soaring Temple of the Inscriptions in which Pakal was buried. Because of her red skeleton, she was called “The Red Queen” by archeologists. Her Mayan name was Tz’aakb’u Ahau, “Maker of a Progression of Lords.” And she certainly did produce a succession of lords, as two of her sons became rulers after Pakal’s death, and a third son fathered the next ruler, Pakal’s grandson.

These scant facts underlie my story about Tz’aakb’u Ahau, whom I give the birth name Lalak. Fleshing out her personality, her hopes and fears, her emotions, and choices she made through her life was my challenge as a writer of historical fiction.

Lalak in my story lived over thirteen centuries ago, but her yearnings and challenges would sound familiar to modern women. She wanted to fit into her new city, find acceptance by her new family, fulfill her obligations in life, and most of all, win the heart of her new husband. What makes Lalak’s situation different is that she faced an arranged marriage with the most powerful young ruler in that Maya region, who just happened to be in love with someone else. Lalak was immediately attracted to him and loved him deeply, but he remained distant. She learned that her mother-in-law had banished the woman he wanted; choosing Lalak as his wife in the hope he would never love her – a homely, shy, and naive girl. Lalak came from a small outlying city, and although she had pristine blood lines making her eligible for such a match, her childhood was chaotic due to family enmities and she lacked preparation for high court protocols and intrigues.

Tz’aakb’u Ahau

The Red Queen

Wife of Pakal, called Lalak in this story

Poorly equipped to meet such challenges, Lalak struggled to find her place and understand the dynamics of Palenque’s ruling family. She suffered under her mother-in-law’s criticism and faced repeated losses through miscarriages. She must grow from a naive and innocent girl into a strong woman capable of fulfilling a queen’s role. Her quest to find a way into Pakal’s heart required developing her feminine powers and expanding her wisdom, assuming her rightful status by facing down her mother-in-law and gaining respect from the sophisticated nobles of her city.

As Lalak‘s story unfolds against the rich backdrop of the Maya Classic Period, you will be immersed in fascinating aspects of Maya culture. There are frightening Underworld journeys where Death Lords hover, calendar rituals requiring the ultimate offering of one’s own blood, and use of sexual alchemy to resurrect lost portals to the Gods and Ancestors. Details of daily life contrast with the dazzling opulence of high court rituals, herbal and healing lore mixes with the sensuous dance and gastronomic delights of feasts, and the amazing advanced knowledge the Mayas had about building construction and astronomy is revealed.

Temple of Inscriptions – Temple XIII – Temple of Skull (c.700) in Palenque, Chiapas, MX

The Queens of Palenque

I became fascinated by women rulers, “queens” in European context, when visiting the ruins of Palenque. This popular tourist destination is set in deep in tropical jungles of Chiapas, Mexico, partway up a high mountain range. Palenque is perhaps the most beautiful, artistically rich, and mystical of Maya sites and contains a huge number of hieroglyphs. These intriguing glyphs of Classic Mayan language provide one of the most complete dynastic histories, carved on panels, tablets, and painted on ceramics. I was enthralled by seeing the Red Queen’s tomb and sarcophagus, and found a book in Spanish while living in Merida called La Reina Roja by Adriana Malvido. Adriana is a Mexican journalist who covered the story of the archeological team that uncovered this hidden tomb in Temple XIII. Fortunately, I read and speak Spanish, and this gem gave me invaluable background. Following leads in the book, I researched the four great queens who the team considered candidates for this burial: Yohl Ik’nal, the grandmother of Pakal; Sak K’uk, the mother of Pakal; Tz’aakb’u Ahau, the wife of Pakal; and K’inuuw Mat, the daughter-in-law of Pakal. I was inspired to write the stories of these four queens, possibly the most powerful women in the Americas, but unknown outside of archeological circles. A lot more study, field trips, and research both in Mexico and the U.S. were required to set their stories in historical context. Three books are finished and published as ebooks; the fourth is in process. My plan is to also publish them as print books, and Book 1 (Yohl Ik’nal) will be released on November 1, 2016!

The Palace Tablet at Palenque

Janaab Pakal on left, Kan Joy Chitam in center, Tz’aakb’u Ahau on right

Buy Book

The Mayan Red Queen: Tz’aakb’u Ahau of Palenque — Book 3

Readers say:

“This is historical fiction at its best, a mesmerizing tale that transforms an archeological mystery into a complex and fascinating flesh and blood woman.”

“This is a novel that beautifully blends history and fiction in an unforgettable story with a mesmerizing and powerful female protagonist.”

If you enjoyed this post, why not join my blog-newsletter?

Click here: 13 Rabbit Scribe

August 6, 2016

Photography Comes to Palenque

Temple of the Inscriptions in 1895

Maudslay photo from Meosweb

Excerpts from the archeological field journal of Francesca Nokom Gutierrez, fictional archeologist in the Mists of Palenque series. Early photography in Palenque by Desire de Charnay, Teobert Maler, and Alfred Maudslay is described by Francesca in The Controversial Mayan Queen: Sak K’uk of Palenque , Book 2 in the Mayan queens’ series.

Photography initiated a new era in documentation of Maya ruins.

Before the camera, on-site drawings or white paper cast molds were the best techniques available. Drawings depended on the skill and perseverance of the artist, and molds were subject to melting in the extremely wet and humid tropical climate. In 1839 Daguerre invented the first camera using a complicated “wet” chemical process. The enterprising French explorer Desiré de Charnay used this camera on his expedition to Palenque in 1860. He spent nine days there, using the cumbersome process to take the first photos of the ruins.

Desire De Charnay on expedition to Maya ruins

One important image shows the central tablet from the Temple of the Cross. Charnay found it where John L. Stephens and Frederick Catherwood saw it earlier, described in their popular book Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan (1841). It was abjectly lying by a stream and covered with muddy debris. Charnay cleaned it and lifted it sideways for better light, taking the first photo of this famous piece. The missing right tablet had found its way to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Partly due to Charnay’s work, all three tablets have now been united in Mexico’s Museo Nacional de Antropología.

A folio of Charnay’s photographs of Palenque and other Maya sites was issued in 1863. This prompted Australian Teobert Maler to launch his field career in photographic documentation of Maya sites. In the summer of 1877, he went to Palenque and took a series of excellent photos of the Palace and Cross Group, using the cumbersome wet process with a large format camera. His photos are the clearest early images of tablets, stelae, and lintels from Palenque and a wide range of undiscovered sites. What lay behind these discoveries was chicle, the basic ingredient of chewing gum, increasingly popular with North Americans. Chicle trees grew abundantly in Central American tropical forests, and opportunistic chicleros cut hundreds of trails through the Peten that uncovered dozens of unknown Maya cities.

De Charnay photo of mask in Izamal

Maler photo of stela at Seibal

Maler received funding from Harvard’s Peabody Museum to explore and survey these newly found sites, and from 1901 to 1911 he took numerous excellent photographic plates of sites now called Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, Seibal, and Tikal. The accuracy of his work provided a foundation for later decipherment of Maya glyphs.

English explorer Alfred P. Maudslay took invaluable photos at Palenque in 1891, producing exceptionally clear images of sculptures and glyphs. Technical progress in cameras made his work possible. Factory-made, ready-to-use photographic dry plates became available three years before his expedition. Images taken by new cameras on dry plates were far superior to the old wet plate process. Maudslay also made paper molds of stone and stucco reliefs, facing the same issues as Charnay. In one disastrous rainstorm, three weeks of molds were transformed into a sodden blob, so the tedious procedure had to be done over.

The trip that Maudslay made to Palenque interests me since it reveals much about the region and its people, my people. From Progreso at the northern tip of the Yucatan Peninsula, he took a boat bound for Frontera at the mouth of the Grijalva River. A bad storm forced them into port at Laguna de Terminos (now Ciudad del Carmen), the lagoon outlet of the other navigable river leading to the Usumacinta, the major artery of river travel. After two weeks clearing customs despite ample official permissions from the Mexican government, he secured a small steamer to take his equipment up-river to the village of Montecristo (now Emiliano Zapata). Finding pack-mules and carriers was difficult and he faced the same problems that plagued most expeditions of his time.

Maudslay commented: “As the Indians had all been hopelessly drunk the night before, we did not get off very early, although our efforts to start commenced before dawn, and what with bad mules, sulky muleteers, and half-drunken Indians we had a hard day of it.”

The ruins of Palenque were 40 miles from Montecristo, so they went first to Santo Domingo de Palenque (my village). Maudslay described it as a sleepy little village of twenty houses with one grassy street

Maudslay photo standing in Palenque Palace Tower

leading to a thatched church. A few white stucco houses lined the grassy square, with Indian huts (palapas) scattered around. When Chiapas was part of Guatemala, the town was on the main trade route but this commerce had been diverted. The village was struck by cholera that wiped out half the population. Many of the homes were abandoned and falling into ruin. Palenque village was “so far out of the world” that he was surprised to find the two most important inhabitants were sons of a Frenchman and a Swiss doctor.

Trouble with workers seemed endemic. Maudslay asked for 30 laborers, and the jefe políticos (leaders) of local towns promised them, but only 15 showed up and that quickly dwindled to three. Finally, he got 20 men from the nearby Chol Maya village of Tumbala (my grandmother’s family is from there). His team included an engineer, a young Frenchman planning to write books about his travels, and some cooks. At the Palenque ruins, they set up beds and camp furniture in the Palace corridor by the eastern court, supposedly the driest area. “Driest” was a relative term, however.

Maudslay wrote: “The great forest around us hung heavy with wet, the roof above us was dripping water like a slow and heavy rainfall, and the walls were glistening and running with moisture . . .”

Palace at Palenque in 1890, Maudslay photo

Despite unpredictable laborers, Maudslay’s team managed to cut down many trees around the structures, clear out the Palace eastern court, and remove all but one of the trees growing from the Palace Tower. The top story of the Tower was half destroyed and the whole in danger of falling over in heavy winds. To prepare Palace piers for photography, they had to remove limestone incrustations that formed small stalactites on the pier faces. The limestone coating varied from a thin film to 5 or 6 inches thick, and it took six weeks to remove it carefully with hammer taps and scraping. Underneath they found colors of the stucco paintings still fresh and bright in some places.

Next was photography, requiring platforms supported by scaffolding. The piers sat on narrow terracesabove stairways, and Maudslay needed to get enough distance to frame good pictures. His engineer made plane-table surveys of the site center, producing detailed floor plans of the Palace and other structures that are still among the most accurate ever done.

Maudslay suffered from malaria contracted in Nicaragua, but his health was good during the four months at Palenque. Despite many difficulties and “hot and mosquito-plagued nights” he recalled pleasures such as finding a cool breezy spot, where they escaped mosquito attacks and enjoyed “the beauty of the moonlit nights when we sat smoking and chatting on the western terrace looking onto the illumined face of the ruin (Temple of the Inscriptions) and the dark forest behind it . . . ”

Maudslay sketching in Casa de Monjas, Chichen Itza

Maudslay photo of Temple I at Tikal

Maudslay photo of stela at Copan

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS POST, WHY NOT JOIN MY BLOG NEWSLETTER!

Click here: 13RabbitScribe

The Controversial Mayan Queen: Sak K’uk of Palenque

Buy Here

June 18, 2016

Palenque Goes International: Stephens & Catherwood

Catherwood Drawing of Palenque

Excerpts from The Visionary Mayan Queen: Yohl Ik’nal of Palenque

The Travel Writers of Their TimeThanks to the remarkable four-volume books Incidents of Travel, by John L. Stephens and Frederick Catherwood, we are given much insight into the hardships of travel and the impact of this splendid and high civilization on these explorers.

John Lloyd Stephens

John Lloyd Stephens is a masterful storyteller and Frederick Catherwood a fine artist. Their first two-volume book, featuring Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan, was published in 1841. It became an instant success, with publisher Harper and Brothers in New York making 11

Frederick Catherwood

printings of 20,000 copies each in only three months. I keep a copy with me to enjoy comparing their impressions with present-day Palenque. Although his prose is typical for that period, it’s richly descriptive and amusing. Stephens weaves details of their harrowing adventures, gives astute character profiles, evocative descriptions and levelheaded reasoning, spiced with wry humor. Catherwood provides distinctive drawings and quality architectural designs with floor plans, elevations and outside views of Palenque’s major structures. Thirty-one of his Palenque drawings were converted to engravings and published in the two Central American volumes.

You get a real sense of travel in the mid-1800s in the back-country of Mexico and Central America.

Stephens and Catherwood came from Guatemala to Ocosingo and followed the same route Dupaix took thirty years earlier, an ancient Indian path over mountains giving “one of the grandest, wildest, and most sublime scenes I ever beheld.” They made the trip in five days to reduce nights in the wild during the rainy season. Clambering along steep paths hovering over thousand-foot precipices, they mostly walked leading mules and occasionally risked being carried in a chair by an Indian using a tumpline across his forehead. The chair-bearer’s heavy breathing,

Trek over mountains

Catherwood carried in “silla” by Maya bearer

dripping sweat and trembling limbs failed to inspire confidence and made them feel guilty, so they used the chair very little. The descent was even more terrible than the ascent, and the sun was sinking. Dark clouds and thunder gave way to a violent rainstorm, men and mules slipping and sliding. Stephens admits “. . . it was the worst mountain I ever encountered in that or any other country, and, under our apprehension of the storm, I will venture to say that no travelers ever descended in less time.”

Once on the plains below and camped for the night, they suffered an onslaught of “moschetoes as we had not before experienced.” Even fire and cigars could not keep the vicious insects at bay. After a sleepless and much-bitten night, Stephens went before daylight to the nearby shallow river “and stretched myself out on the gravelly bottom, where the water was barely deep enough to run over my body. It was the first comfortable moment I had had.”

“Moschetoes” and rainstorms continued to plague the explorers after they arrived at the ruins of Palenque. They no sooner got their wood frame beds and stone slab dining table set up, with a meal of chicken, beans, rice and cold tortillas prepared proudly by their mozo Juan, than a loud thunderclap

Catherwood Drawing

Palenque Palace Interior

heralded the afternoon storm. Though located on the upper terrace of the palace and covered by a roof, the fierce wind blasted through open doors followed instantly by a deluge that soaked everything. They moved to an inside corridor but still could not escape the rain, and slept with clothes and bedding thoroughly wet.

Rather, they tried to sleep but “suffered terribly from moschetoes, the noise and stings of which drove away sleep. In the middle of the night I took up my mat to escape from these murderers of rest.” Finding a low damp passage near the foot of the palace tower, Stephens crawled inside and spread his mat as bats whizzed through the passage. However, the bats drove away the mosquitoes, the damp passage was cooling and refreshing, and “with some twinging apprehensions of the snakes and reptiles, lizards and scorpions, which infest the ruins, I fell asleep.”

They solved the mosquito problem by bending sticks over their wood beds and sewing their sheets together, draping them over the sticks to form a mosquito net. Not all insects were odious. At night the darkness of the palace was lighted by huge fireflies of “extraordinary size and brilliance” that flew through corridors or clung to walls. Called locuyos, they were half an inch long and had luminescent spots by their eyes and under their wings. “Four of them together threw a brilliant light for several yards around” and one alone gave enough light to read a newspaper.

Exploring the Ruins

To explore the heavily forested ruins they hired a guide, the same man employed by Waldeck, Walker and Caddy. It’s hard now to imagine how dense the jungle was then, trees growing on top of every structure and filling plazas. Without the guide, they had no idea where other structures lay and “might have gone within a hundred feet of all the buildings without discovering one of them.” The palace was most visible and could be seen from the northeast path leading to the ruins. Stephens described its many rooms, stuccos, tablets, and ornaments while Catherwood rendered detailed floor plans and copied images. Stephens hoped their work would give an idea of the “profusion of its ornaments, of their unique and striking character, and of their mournful effect, shrouded by trees.” Perhaps readers could imagine the palace as it once was “perfect in its amplitude and rich decorations, and occupied by the strange people whose portraits and figures now adorn its walls.”

Catherwood Sketch of Palace

Catherwood Drawing

Principle Court of Palace

According to the guide, there were five other buildings that Stephens numbered, but none could be seen from the palace. The closest was Casa 1, a ruined pyramid that apparently had steps on all sides, now thrown down by trees that required them to “clamber over stones, aiding the feet by clinging to the branches.” From descriptions and drawings, this structure is the Pyramid of the Inscriptions. Bas-relief stuccos on the four piers of the upper temple were reasonably well preserved, depicting four standing figures holding infants. The famous hieroglyphic tablets covering the interior wall were also in good condition.

Catherwood Sketch and Architectural Floor Plan

Temple of Inscriptions

Casas 2, 3 and 5 are part of the Cross Group. Stephens and Catherwood were deeply impressed by the stuccos and tablets that we now know belong to the Temple of the Cross and Temple of the Foliated Cross. The fantastic tablets from the first temple were incomplete and only the left tablet containing glyphs was in place. The middle tablet with two figures facing a cross had been removed and carried down the side of the pyramid, but deposited near the stream bank below. A villager intended to take it home, but was stopped by government orders forbidding further removal from the ruins. The right tablet was broken and fragmented, but from remnants they saw it contained more glyphs.

The second temple contained another tablet in near-perfect condition. It had a central panel with two figures facing a large mask over two crossed batons, flanked on each side by panels of glyphs. The four piers of the temple’s entrance once contained sculptures; the outer two adorned with large medallions were still in place. The other two panels had been removed by villagers and set into the wall of a house. Copied earlier by Catherwood, these panels depicted two men facing each other. One was richly dressed and regal, the other an old man in jaguar pelt smoking a pipe. Later these famous sculptures were moved to the village church, and again later to the Palenque museum.

Temple of Foliated Cross

L. Schele drawing, FAMSI

Smoking Lord, Temple of the Cross – L. Schele drawing, FAMSI

Casa 4 was farthest away, southwest of the palace. It sat on a pyramid 100 feet above the bank of the river with the front wall entirely collapsed. The large stucco tablet inside showed the bottom half of a figure sitting on a double-headed jaguar throne, the lovely Beau Relief partially destroyed by Waldeck. Stephens regretted this loss greatly (as do I) because it appeared to be “superior in execution to any other stucco relief in Palenque.” This small structure is now called Temple of the Jaguar.

The Beau Relief

This story is told in my post:

The Palenque Beau Relief: A Maya Beauty Vanishes.

Difficult Working Conditions

Temple of the Inscriptions in 1895

Maudslay photo from Meosweb

Stephens complains that artists of former expeditions failed to reproduce the detailed glyphs in Casas 1 and 3, and omitted drawings of Casa 2 altogether. He believes these artists were “incapable of the labour, and the steady, determined perseverance required for drawing such complicated, unintelligible, and anomalous characters.” Catherwood used a camera lucida to project a light image of the glyphs and sculptures onto paper, and then drew the images to accurate scale and detail. He divided his paper into squares for copying glyphs to give accurate placement, reducing these large images and hand correcting the later engravings himself.

One must admire these two men, working under terrible conditions with limited equipment, yet providing such a thorough account of the Palenque structures they saw. They needed to scrape off green moss, dig out roots, clean away layers of dissolved limestone, use candles to light dark inner chambers, build scaffolds to access high places, and endure a plethora of climate and insect assaults. They paid the price of multiple mosquito bites, for both men contracted malaria and suffered repeated episodes of illness.

They left us a few astute conclusions. Stephens proved more insightful than later Mayanists by writing, “The hieroglyphics doubtless tell its history” and “The hieroglyphics are the same as were found at Copan and Quirigua . . . there is room for belief that the whole of this country was once occupied by the same race, speaking the same language . . .”

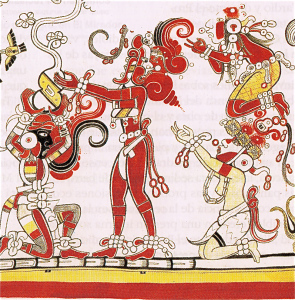

Itzamna Painted on Vase Performing Ritual

“Here were the remains of a cultivated, polished, and peculiar people, who had passed through all the stages incident to the rise and fall of nations; reached their golden age, and perished, entirely unknown . . . wherever we moved we saw the evidences of their taste, their skill in arts, their wealth and power.” John Lloyd Stephens

Excerpts from The Visionary Mayan Queen: Yohl Ik’nal of Palenque

These excerpts from the Archeological Field Journal of Francesca Nokom Gutierrez, a fictional archeologist in my books, describe the history of archeological exploration at Palenque. I’ll be doing several posts taken from her journal in the first 3 books in my “Mists of Palenque” series.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS POST, WHY NOT JOIN MY BLOG NEWSLETTER?

Click here: 13 Rabbit Scribe

June 2, 2016

Palenque’s Early Explorers

Palace at Palenque

Excerpts from The Visionary Mayan Queen: Yohl Ik’nal of Palenque

Early explorers: Del Rio, Armendariz, Dupaix, Waldeck, Walker-Caddy

In the 1780s, a couple of Spanish expeditions came to Palenque and made crude drawings of structures and art. The King of Spain was interested in the geography and history of his overseas colonies, and dispatched Artillery Captain Antonio del Rio from Guatemala to bring away samples. Del Rio removed stucco hieroglyphs, parts of figures and small panels that now reside in Madrid’s Museo de America.

Bas relief sketch by Armendariz, 1787

Numerous drawings by artist Ignacio Armendariz from this expedition were the first reasonably accurate reproductions of Palenque’s huge array of art.

Another Spanish expedition in the early 1800s produced 27 drawings of panels and tablets, floor plans, and sketches of buildings, a bridge and aqueduct. Guillermo Dupaix, Dragoon Captain stationed in Mexico, and artist Jose Luciano Castaneda took a 50-mile trek from Ciudad Real (now San Cristobal de las Casas) to Palenque that required eight days on a trail winding through mountains that were “scarcely passable by any other animal than a bird.” Unfortunately, the work of these two Spanish artists got confounded and appeared in a book by Alexander von Humboldt in 1810 labeled as “Mexican reliefs found in Oaxaca,” a city nowhere near

Castaneda drawing of Temple of Inscriptions

Palenque.

The flamboyant artist, traveler and antiquarian, self-styled “count” Jean-Frederic Maximilien de Waldeck adapted Armendariz-Castaneda’s art with his own embellishments of musculature and costumes that gave a distinctly Roman look. Waldeck, like some other early explorers, believed the people who built these cities came from the “old world,” perhaps Rome, India or Egypt. This art appeared in an 1822 publication of the del Rio report, with many images copied into Lord Kingsborough’s sumptuous volume the Antiquities of Mexico in 1829. Waldeck resided at Palenque in 1832, building a pole-and-thatch house near the Temple of the Cross and recruiting a local Maya girl as his housekeeper. The structure called Temple of the Count is named for him. He made numerous drawings of reliefs and glyphs, some were careful reproductions but many were fanciful with evocative views of buildings and romantic landscapes used later for paintings and lithographs.

Waldeck drawing of Palace Tower

Waldeck drawing of elephant head on Palace wall

I can forgive Waldeck for many of his absurdities, such as including elephant heads and Hindu designs in renditions of Maya art. But I cannot forgive him for partially destroying one of Palenque’s loveliest stucco sculptures, the “Beau-relief” that once adorned the Temple of the Jaguar. It depicts a graceful figure with flowing headdress and geometric-patterned skirt, seated on layered cushions upon a double-headed jaguar throne. The figure’s arms and legs hold elegant, ballet-like poses. Waldeck did draw the figure first, as did Armendariz half-a-century earlier. Why he destroyed it is a mystery.

The Beau Relief drawn by

Jean-Frederic Waldeck

These drawings were reproduced in a number of books and magazines, and caught the attention of two men in the United States who really “put Palenque on the map;” John Lloyd Stephens, American popular travel writer and Frederick Catherwood, English architect and illustrator. Intrigued by the fantastic images and cities depicted, they determined to travel in search of Maya ruins and publish a book with illustrations about these wondrous things. They went first to Belize to visit Copan (now in Honduras), and then planned visits to Uxmal, Palenque and other sites.

Belize was under British control then, and some international competition got sparked. Patrick Walker, aide to the superintendent of British Honduras, and Lt. John Caddy of the Royal Artillery heard about Stephens and Catherwood’s plans to visit Palenque. Irked that the American expedition might reach Palenque before the British, Walker and Caddy quickly put together their own expedition. The Britons planned to reach Palenque first by going due west along the Belize River and across the Peten in Guatemala. They endured a grueling journey through swamps and jungles, arriving two months ahead of the American team.

Walker and Caddy made some quite accurate drawings of figures, panels and buildings and produced a report that remained unpublished for over 125 years. Their primary goal seemed to be winning the race

Caddy drawing of interior House A, Palace

with the American team, and Walker’s greatest interest was hunting game along the way. Caddy’s report did make prophetic observations; saying that the massive buildings, elegant bas reliefs, and beautiful ornaments prove that in ancient times the city was inhabited by “a race both populous and civilized.” He also concluded that many more buildings once stood at the site that extended for several leagues. One entry remarked on a Spanish manuscript from around 1796, in which the local priest claimed that he “discovered the true origin” of these ancient people because of their “perfect knowledge of the Mythology of the Chaldeans.”

Excerpt taken from The Visionary Mayan Queen: Yohl Ik’nal of Palenque.

These excerpts taken from the Archeological Field Journal of Francesca Nokom Gutierrez, a fictional archeologist in my books, describe the history of archeological exploration at Palenque. I’ll be doing several posts taken from her journal in the first 3 books in my “Mists of Palenque” series.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS POST, WHY NOT JOIN MY BLOG NEWSLETTER?

Click here: 13 Rabbit Scribe

April 23, 2016

Maya Cement: The Glue of Great Cities

Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico

The ancient Mayas built thousands of cities throughout their 125,000 square mile realm. Ruins of huge Maya cities have been dated back to 300-400 BCE. No doubt smaller cities were being built centuries before, but the fragile wood and thatch building materials degraded over time. By the Late Preclassic Period (400 BCE—250 CE) the technology for building stone structures had been perfected. This technology created tall pyramids, expansive palaces that reached five stories, and complex residences with interlocking passages and plazas. These strong and durable structures were able to withstand 3,000 years of harsh environment, earthquakes, and hurricanes. Even the encroachment of jungle roots and vines since the great cities were abandoned around 1,000 CE could not bring down most of these buildings. Hundreds of high-rise Maya cities remain standing today; a tribute to their building technology.

Edzna Palace with Five Stories

What substance was strong enough to “glue” the building stones together for so many centuries? The answer is found in Maya cement. Maya technicians invented a method for producing hydraulic cement from native limestone before 250 BCE. How they discovered this process is a mystery, since it requires extremely high temperatures in a type of “blast furnace” to convert limestone into cement. Archeologists surmise they used trial-and-error over many years, perhaps a millennium, to get the formula right. We can imagine ancient Mayas watching a huge conflagration from lightning strikes in forests, or set off by volcanic flow or cinders, that created super-heated fire. After the burning was reduced to coals and ashes, they saw peculiar round globules sitting on top, where before there were chunks of limestone. As rain moistened the globules, they puffed up into a grey-white powder. Curious, the Maya collected the powder and started experimenting with its properties. After mixing it with pebbles or clay or other substances, and adding water, they found that it made a very hard, durable bonding material. Claro que si! Cement was converted to concrete.

Maya cement was used for making cast-in-place concrete, the “glue” that held together their stone buildings and the base material for stucco that coated Maya structures, roads, cisterns, and plazas.

Hydraulic cement – the Mayas made true hydraulic cement, first used by the Romans. This cement reacts with water to form silicate hydrate crystals; these grow and interlock creating a bond between aggregate mixtures (pebbles, ground limestone, clay) to produce hard, durable construction material called concrete. The cement paste glues together the aggregate mixture, fills voids, and increases strength as it stiffens, called “setting up.” As the concrete hardens, it continues increasing in strength and durability. Maya cement is similar in chemical makeup to modern Portland cement, which is the current standard.

Maya Kiln Model

By James O’Kon. The Lost Secrets of Maya Technology

Maya cement kiln – the Maya cement firing kiln has similar thermodynamic and chemical properties to a blast furnace. Calcium is the essential chemical component for cement, and the Mayas had an abundant supply of limestone. When heated to 1450-1600 degrees C (2642-2912 F) the limestone melts, inducing a chemical reaction to form calcium silicate. These take the shape of globules called “clinkers.” Wood was the Maya fuel source, and generally it does not produce high enough temperatures, normally

Clinker Nodules

Wikipedia

reaching 300-400 degrees C (572-752 F). Learning that a higher temperature was needed, the Mayas invented a kiln. They stacked wood in a circular design set on an elevated platform of spaced rocks. The center of the circle was left open. The kiln diameter was around 6 meters (19.7 feet) across and 2 meters (6.6 ft) height. Logs were stacked horizontally in a radial pattern, larger logs filled in with smaller ones and chinked solid with chipped wood. A vertical shaft was left open up the center, 8 inches diameter, extending from ground level to the top of the pile. To keep the kiln burning the required 24-30 hours, the wood had to contain enough moisture. It was either green wood or it was moistened with water. Readily combustible material such as dry leaves and dry decayed or resinous wood was put at the shaft base to ignite the kiln.

Raw limestone was cut into small blocks and stacked on top of the wood pile, to a height of 0.75 meters (2.5 ft.). The dry tinder was set afire, and its rapid burning sucked in cool, oxygen-rich outside air through the elevated base of the platform. As this air entered it increased the temperature in the center core while reducing ambient pressure. In turn, the reduced pressure induced a rapid flow of cooler, oxygen-rich air which then increased the temperature even more. This super-heated air was exhausted upward into the limestone, in a chimney-like effect. This cycle kept raising temperature and burning the stacked wood at temperatures that reached 1600 C (2912 F). When the kiln was at peak operation, a narrow tongue of flame soared skyward to a height of 30 meters (98.4 ft.). As heat increased, the flame color changed from red to orange, then yellow and finally to blue, which indicates 1600 C.

When the burn was complete, a collection of clinkers sat upon a pile of cinders. These were allowed to cool. Exposure to dew and rain caused the clinkers to expand into a dome of fluffy grey-white powder, 5-6 times the bulk of the limestone. This powder was hydraulic cement, and could be ground finer as needed. The cement was combined with the aggregate mixture and water to make cast-in-place concrete: one part cement, 3 parts loosely ground limestone or other aggregate, and water. Five tons of wood were required to produce one ton of cement.

Weather conditions had to be just right to make cement: clear weather with zero chance of precipitation, and no wind. Wind would cause higher burn rates at the windward side leading to collapse of the kiln structure.

Itzamna Painted on Vase Performing Ritual

Rituals accompanied the kiln burning. Women were not permitted near the kiln during the burning, since the kiln, considered to be feminine, would become jealous and refuse to operate properly.

Studies have shown that Maya cement has almost the same chemical composition as Portland cement, meeting strict international standards for manufactured cement. Maya cast-in-place concrete has higher strength than needed by the loads superimposed on Maya structures. It has remarkable ability to resist severe environmental exposure. Its high compressive strength is greater than building materials of any other ancient American culture.

Conclusion: Maya cement is a true cement, a building material very similar to modern cement. Its properties produce concrete with a strong matrix, similar to modern concrete.

Wall using Maya concrete

Chichen Itza Ballcourt

Columns using Maya concrete

Chichen Itza Temple of Warriors

James A. O’Kon, PE. The Lost Secrets of Maya Technology. Career Press: New Page Books, Pompton Plains, NJ. 2012. In depth explanations of many types of Maya technological achievements, by an “archeoengineer” who spent 40 years investigating at over 50 remote Maya sites.

March 9, 2016

Maya Exhibit: Ceramics, Art & Adornment

Balboa Park, San Diego Museum of Natural History.

While in San Diego for the holidays in December, 2016, I spent a mesmerizing afternoon in the Maya Exhibit at the Museum of Natural History, Balboa Park. This wonderful display of Maya monuments, ceramics, and art had many original pieces on loan from other institutions, as well as reproductions of murals and larger monuments. In this blogpost, I’ll focus on ceramics, adornment and artwork.

Clay Vase with Effigy

Ceramics

The Mayas produced a wide variety of beautiful and intricately designed ceramics. Artists were allowed quite a free range of expression, their designs varying from one workshop to another. Artistic quality was more valued than adherence to standardized forms, and certain artists’ works were in high demand among elite. Some artists signed their works, or named the bowls for their owners and functions: “The cacao drinking vase of Ahau Ukib.” These vessels with detailed scenes were used in the form of straight-sided beakers for drinking chocolate mixed with chili peppers, or as bowls for food. Often they

Simple Clay Vessels

were used as grave offerings in the tombs of their owners. Simpler and more utilitarian vessels were used by commoners.

To produce pottery, the Mayas used a device that rotated between the potters’ feet, called a kabal. An early ceramic style, called Amyan, appeared in the Guatemalan highlands around 1,000 BCE. It was monochrome with simple design. Originally the Mayas used gourds cut into cup and bowl shapes, and the first ceramics resembled gourds. These were decorated with rocker stamps and simple slips for color. By the Early Classic (250-550 CE) the ceramic style Tzakol developed with more complex jars, plates, bowls and vases having polychrome decorations. This style evolved into Tepeu of the Late Classic (550-700 CE) with more elaborate scenes and color variations. The polychrome slip paint was of various colors, made from plant and mineral sources. Predominant colors are red, orange, black, brown, yellow and cream. These two ceramic styles are considered the most beautiful made in ancient Mesoamerica, primarily depicting animal deities, grotesque monsters, nobles and priests, ceremonial activities, and scenes of sacrifice. New shapes were developed, including the lidded basal flange bowl, which usually had a knob on top in the form of an animal or human head. The painted body of this being often spreads across the pot. Many also had tetrapod legs for support, called “mammiform” since they resembled animal or human legs.

Polychrome Cups and Decorated Bowl

Tripod Vase with Human Head, Teotihuacan

Straight-sided Drinking Cup, Orange on Cream Slip

An especially valued polychrome called “Codex style” was produced during the late Classic re-occupation of the pre-Classic sites El Mirador and Nakbe in Guatemala. These ceramics are characterized by scenes and glyphic texts drawn in dark lines on cream-colored backgrounds, usually framed by red bands on the

Polychrome Codex-style Vase

edges of the vessels. This gives them a resemblance to the post-Classic Maya Codex texts. This fine painted Codex-style pottery depicts extraordinary mythological scenes, and is highly sought by antiquities collectors, accounting for extensive looting of house mound complexes in Peten. In ancient times, these ceramics were in demand by elites, and have been found throughout the Maya regions.

Figurines and Effigies

The Mayas created many small figurines, busts and effigies that represented deities, specific individuals, symbolic monsters or creatures, or roles in society. Materials used to create them include clay, limestone, sandstone, trachyte, wood, jade, bone, shell, and copper. Very few artifacts were made of gold. As these often depict typical activities of ancient Maya life, archaeologists have learned much about costumes, musical instruments, religious rituals, household customs, ballgames, warfare and sacrifice. Among the most well known figurines are those from Jaina, an island off the coast of Campeche, Mexico, used for elite burials.

Figurine of Ruler in Bloodletting Position

“Incensario” Effigy of God, for Burning Incense

Bust of Janaab Pakal, Ruler of Palenque

Figurines were painted with the usual plant and mineral pigments. A unique shade of blue appears on some figurines, and in many murals and codices. Called “Maya blue,” it is the most durable Maya color and has only recently been reproduced. The ancient Mayas combined skills in organic chemistry and mineralogy in their technique for creating Maya blue. The pigment is a composite of organic and inorganic constituents, primarily indigo dyes derived from the leaves of the anil (Indigofera) plant, combined with palygorskite, a natural clay. The mix is cooked at low temperature (100 degrees C) until its color turns from blackish to this exquisite sky blue. Other trace elements are present, including copal incense, leading to the idea that producing Maya blue was a sacred process. Copal, resin of a native tree, is dried into incense and burned in symbolic “incensarios” during ceremonies. Using copal in making Maya blue produces the low heat necessary, and imbues the pigment with sacred qualities.

Royal Woman Wearing Maya Blue Adornments

Bonampak Murals

Jewelry and Body Decoration

Body adornment was very important to ancient Mayas. They dressed in lavish costumes, wore huge and heavy jewelry, wore complex headdresses with feathers and decorations, had earplugs that needed a balance weight behind, and often embedded gems in their teeth. Facial scarification was also used along with body painting. The Mayas excelled in working with jade, which was highly prized, as it represented the green vibrancy of new plants and the azure of water. Excavations of tombs have yielded large amounts of jade jewelry, mosaics, masks, effigies, plaques and small figures. Royal burials rich in these items have been found in several Maya sites, particularly Palenque, El Peru-Waka, and Tonina. Metal work did not make a significant appearance until after 900 CE, the Post-Classic Period. The Mayas mostly worked in copper, with a small amount of gold appearing as bowls, cups, rings, and effigies. Other items made from copper include bells, tweezers, axes, earplugs, rings, discs, and small masks.

Teeth Embedded With Jade and Stones

Small Jade Mask of Maya Noble

Jade Necklace

February 12, 2016

Maya Exhibit: Murals and Monuments

Balboa Park, San Diego Museum Complex

Maya Exhibit: Murals and Monuments

Balboa Park, San Diego Museum of Natural History

In December, 2016, while spending holidays with family in San Diego, I was fortunate to find a Maya exhibit at the Museum of Natural History in Balboa Park. After warning my family that I would spend hours perusing the exhibit, camera in hand, I was not surprised that no one wanted to accompany me. Alone and mesmerized by the wonderful display of Maya monuments, ceramics and art, I spent a most enjoyable afternoon. Many original pieces were on exhibit, loaned from other institutions, as well as reproductions of murals and larger monuments. In this blogpost, I’ll focus on murals and monuments, with other posts to follow for ceramics and artwork.

San Bartolo Mural

The Murals at San Bartolo, Guatemala

In 2001 William Saturno, of the University of New Hampshire and Harvard’s Peabody Museum, found an entrance into buried chambers while seeking shade. He ducked into a looters’ trench in an unexcavated pyramid, and when he shone his flashlight on the walls, he saw an elaborate, finely-painted mural. Called “Las Pinturas,” the structure’s murals were dated from 100 BCE and showed mythological scenes related to the origin of kings. Later excavations revealed additional murals, called a masterpiece of ancient Maya art. The 30 x 3 foot mural on the west wall reveals the Maya story of creation, the mythology of kingship and divine right of kings, and depicts two coronation scenes—one mythological and the other an actual king’s coronation. Other discoveries at the site include the oldest known Maya royal burial, around 150 BCE, and significantly older painted polychrome murals in a deeper chamber with Maize God images, dated around 200—400 BCE. Glyphs within the murals date to centuries before most other Maya texts, and remain hard to read. David Stuart of the University of Texas at Austin, leading Maya epigrapher, said one scene names a young god as “star man” and emphasizes his cosmological role within the larger creation myth represented.

The San Bartolo mural featured at Balboa Park is the scene of the Maya creation myth, the first known depiction in narrative form, according to Karl Taube, University of California, Riverside, an expert in ancient Mesoamerican history.

San Bartolo Mural Redrawn from Heather Hurst by National Geographic

In this mythological story, the Maize God travels through the underworld and is eventually resurrected, giving birth to the Mayan people. From left to right, the mural begins with an unusual birth scene; four infants scattering from a gourd that may represent the four cardinal directions, while a fifth emerges in the cleft or center of creation. A supernatural being with a serpent headdress witnesses the birth scene, and to its right is a stylized Flower Mountain that offers passage from the underworld, place of ancestors, to the Earth’s surface. This represents the birth of the people from the mythic cave of origin, depicted as a small serpent emerging from a hole at the base of the mountain. A kneeling woman near the cave offers a ceramic pot of tamales, symbolic of the people being formed from corn. In front of her, a kneeling black-faced man offers water in a gourd, symbolizing the essentials (food and water) needed to sustain life. The pair present their offerings to a red-bodied Maize God, who looks over his shoulder at two stacked kneeling women, waiting to take the offerings from him. They are possibly aspects of the wind goddess. Next is the Maize God’s wife, the only standing woman who is wearing an elaborate bird headdress. Behind her are two black and red figures bearing burdens on their heads and carrying ritual

Maize God in Center of Scene

Woman Kneeling by Flower Mountain

implements in loincloths. They carry sacred objects for the Maize God and his wife. The final figure is an immense serpent whose body underlies the entire scene. Its tail emerges from Flower Mountain and its upturned head with open mouth emits large red speech scrolls. Black footprints along the red part of the snake’s body indicate it is a path for supernatural travel. The snake-as-ground motif is found widely in Mesoamerica. The Maize God is the central figure in the scene, personification of cycles of life, death and rebirth. The woman may be dressing him for his journey to death and resurrection. Red spirals coming from his mouth indicate breath and speech. Two short columns of glyphs between the bearers are ancient, hundreds of years earlier than most known Maya glyphs.

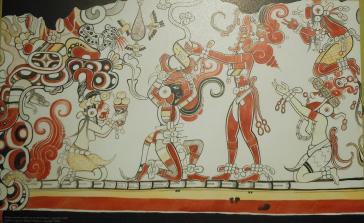

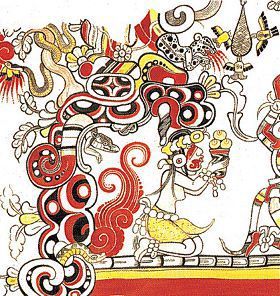

Murals at Bonampak Procession of Lords

The Murals at Bonampak, Chiapas, Mexico

The Bonampak murals are perhaps the best known of all Maya wall paintings. Lying close to a tributary of the Usumacinta River, it was first seen by non-Mayans in 1946, but it’s unclear who first visited the site. Two American travelers were led to the ruins by a local Lacandon Maya; his people still visited the site to pray in ancient temples. The site itself is unimpressive, but a small structure on a low hill holds the famous murals. Structure 1 at Bonampak, which holds the murals, was dedicated on November 11, 791 CE. Bonampak had become a satellite community of nearby Yaxchilán, whose ruler Itzamnaaj Bahlam II (Shield Jaguar) appointed his nephew Chan Muwaan II to govern the city in 790 CE. Shield Jaguar hired Yaxchilán artisans to construct the Temple of Murals.

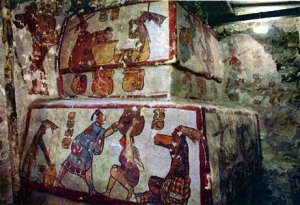

Murals at Bonampak

Ruler and Captives

Structure 1 has three rooms containing murals. The paintings show the story of a single battle and its victorious outcome. Among the best preserved Maya murals, these are noted for their vivid depiction of battle scenes, captive torture, sacrifice, and royal rituals and processions. They also depict women doing self-bloodletting by piercing tongues and earlobes with stingray spines. The battle scenes contradicted early assumptions that the Maya were a peaceful culture of mystics, a position long-held by influential Mesoamerican archaeologist, ethnohistorian and epigrapher from the Carnegie Institute of Washington, Sir John Eric Sidney Thompson.

Colors on the mural are intense and bright, although covered by a film of dissolved limestone when first discovered. Musical Instruments, costumes, body adornment, and weapons are documented from the

Murals at Bonampak

Women Performing Self-Bloodletting

period giving valuable information about Mayan culture. The vivid colored frescos of turquoise blues, yellows and rust colors are a treasure of data about royal life and ceremonies. Unfortunately the murals have deteriorated badly since their discovery. Early archeologists from the Carnegie Institution doused them in kerosene to remove the film and intensify the colors. This weakened the plaster, causing paint and plaster to flake and fall off.

Mary Miller of Yale University, who studied the murals extensively, wrote “Perhaps no single artifact from the ancient New World offers as complex a view of pre-Hispanic society as do the Bonampak paintings. No other work features so many Maya engaged in the life of the court and rendered in such great detail, making the Bonampak murals an unparalleled resource for understanding ancient society.”

Murals at Bonampak

Maya Ruler

Murals at Bonampak

Lord Wearing Solar Disk

Murals at Bonampak

Royal Women

Cut-away Model of Three Chambers in Bonampak Murals

Monuments: A few large replicas of stelae, buildings, plazas and carved frescoes were on display.

Stela from Copan, Honduras

Carved Fresco on Pyramid in Xunantunich, Belize

Mask in Profile facing plaza

Carved Lineage of Rulers of Copan

Bench/Altar

December 15, 2015

Maya “Painted Pyramid” Reveals 1st Murals of Daily Life

Calakmul or Kalakmul is a major site in my historical fiction about the Mayan Queens of Palenque. These two cities were enemies and had numerous skirmishes, several depicted in my stories. The mural shown here is one of the finest in terms of color and details of clothing.

Topic: Maya Food in Daily Life

A series of unusual Maya wall murals, complete with hieroglyphic captions, are providing archaeologists with a priceless look at day-to-day life in the empire circa A.D. 620 to 700.

Previously known Maya murals all depict the ruling elite, victories in battle, or religious themes. (Explore a map of Maya ruins.)

But exterior walls on a “painted pyramid” buried for centuries in the Mexican jungle (pictured, a corner of the pyramid undergoing excavations) have shown Maya scholars something completely different.

The murals—discovered in 2004 at the Maya site of Calakmul—depict ordinary people enjoying much more casual pursuits, according to a new, detailed description of the wall art.

“There’s really nothing like this in any of the [known] murals. These are totally unexpected,” said Maya expert Michael D. Coe, curator emeritus at Yale University’s Peabody Museum of Natural History and editor of the…

View original post 205 more words

November 29, 2015

The Oracle of Cuzamil

The island of Cozumel, called Cuzamil by ancient Mayas, lies off the eastern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. It was a shrine and pilgrimage destination for women, sacred to the goddess Ix Chel. Mayan women made the journey to Cuzamil twice during their lives, at menarche and menopause. They sought the blessings of Ix Chel for a good marriage, fertility, abundance and safe childbearing. Thousands would travel by canoe from Pole, present-day Playa del Carmen, across treacherous currents. The trip took twelve hours, and specially trained men, who understood the shifting currents, rowed the canoes. Legends tell that between 600-800 CE only women and children could live on the island. It was a place of sanctuary for marginal women, and sheltered orphans, widows, barren women and those who crossed sexual boundaries.

Canoe paddlers crossing to Cuzamil

Coastline of Cuzamil

Today in Yucatan, the ritual crossing to Cozumel is held annually, called “La Travesia.” It is a re-creation of the ancient Cuzamil pilgrimage that was lost for over 500 years. The ruins of a city called San Gervasio hint at its former splendor, with columns rising on large platforms, shrines to the goddess and the elements, and a long causeway (sakbe) leading to the landing point for canoes bringing women for pilgrimage. One shrine to Ix Chel holds a carved stone column with a woman giving birth, with imprints of red hands over the carving. Another shrine called “Las Manitas” has a stucco facade with murals

Ix Chel shrine with mural remnants

decorated by designs in black lines on a Maya blue background. To the right side of its facade, Maya visitors left their own red hand prints on the wall, a common practice in the region. Passages run underneath these structures leading to small shrines inside caves, and causeways connect many complexes. The site was abandoned during the 10th century, but it continued as a pilgrimage site, noted by Spanish friars in the early 16th century.

San Gervasio ruins Cozumel

Small shrine San Gervasio

The Oracle of Cuzamil. The Spaniards reported that Mayas sought advice of an oracle on the island of Cuzamil. A large statue of Ix Chel, made either of ceramic or wood, allowed a person to remain concealed inside. Pilgrims would ask the oracle questions, either directly or through a priest, and the Ix Chel priestess inside the statue would give answers. Pilgrims believed the Ix Chel oracle gave true answers to questions about their lives and guidance about which choices to make. It was even reported that the oracle would prophesy outcomes of conflicts and wars.

Oracles exist in many cultures, and usually function under the influence of mind-altering substances. The famous Oracle of Delphi, Greece, who prophesied during the seventh to the fourth centuries BCE,

Oracle of Delphi – Pythia

was said to allow Apollo to possess her body and speak through her. Called Pythia, she sat on a tripod seat over a fissure in the earth. This seat was called the “omphalos” or navel of the world, located in her temple. Myth relates that when Apollo slew the great snake Python, its body fell into this fissure and fumes arose from its decomposition. The priestess breathed these fumes and became intoxicated, falling into a trance during which Apollo spoke through her. Plutarch described that Pythia would lapse into semi-consciousness, and respond to questions in an altered voice. At other times, her trance involved frenzied delirium, with wild thrashing of limbs, groaning and inarticulate cries. After this delirium, she died in a few days and another Pythia took her place.

Columns of Delphi Temple

Delphi Tholos

According to toxicologists, these symptoms are associated with inhalation of hydrocarbon gasses. Similar effects are observed in “huffers” who breathe fumes from glue, paint thinner, or gas. The presence of a sweet smell, which Plutarch reported during Pythia’s trances, indicates the hydrocarbon gas ethylene. Greek geologists have identified a small fracture in the earth extending up from the intersection of two major fault lines running underneath the Delphi temple. The limestone under the temple is bituminous (oil-bearing) with a petrochemical content as high as 20 percent. It appears that slippage in the faults heated adjacent rock masses, vaporizing the lighter petrochemicals in the limestone and expelling gasses upward through the fissure. They believe that gases produced rose up the crack and entered the temple just below the stool on which Pythia sat. Ethylene is known to produce violent trances. Probably when smaller amounts were expelled, the oracle was less affected and was able to speak lucid prophesies.

Ix Chel in Trance – art by Lisa Iris

The Oracle of Cuzamil also used hallucinogenic substances to vacate her body and offer it as a vessel for the goddess Ix Chel.One such substance came from the skin glands of a large bufonid marine toad. A disproportionate number of these toad bones are found in human burials on Cuzamel, probably because of their ritual uses. The poison from toad glands was prepared in special ways, because when ingested it can cause tremors, paralysis, convulsions and death. It appears that the ancient Mayas made it into an enema; these clysters or enema syringes had a distinct glyph and appear frequently in painted ceramics. The clysters were gourds with an elongated, pointed end. Other substances were included, such as concentrate made from crushed Datura flowers and fermented maguey juice. Maguey is an agave plant related to those used for tequila. Datura, which grows wild in regional jungles, is a well-known hallucinogen. The oracle’s preparation probably included ritual purification in a steam bath, infused with herbs such as basil, cedar, vervain and Pay-che; and a period of fasting. She likely smoked potent tobacco in a small clay pipe that also affected her senses. A rare blue-leafed tobacco was grown on Cuzamil that is said to produce a floating sensation and separate consciousness from the body. Morning glory seeds, which alter consciousness, may have been used, along with other herbs, in an ointment to massage the oracle’s skin, opening the path to disembodiment.

After such a potent mixture of hallucinogens, the oracle would be semi-conscious and need assistance walking. She may have been carried by attendants to the temple and helped into the statue, where she probably was tied to a chair or other type of support to prevent falling over. It seems amazing that the oracle could function, much less understand communications and give coherent responses. But, such is

Bufo Toad with ceramic depiction

the sacred mystery of the oracle. Those with mystical leanings will believe that another intelligence took charge of this vessel, emptied of its human awareness and ritually purified. Whether goddess, god or the collective consciousness, this intelligence reached down through the human vessel to deliver messages to seekers.

To be an oracle required extensive training, unwavering commitment and a strong constitution to survive the rigors of the process. Still, oracles did not have a long life expectancy, either in Greece or Cuzamil. The great honor of serving the Goddess and her people drew many young women into training, and the gifts given in appreciation built the wealth of the oracle’s city.

The Oracle of Cuzamil appears in the final book of the Mists of Palenque Series, as youthful K’inuuw Mat makes the sacred pilgrimage to the island of Ix Chel and hopes to remain there to serve the goddess. However, fate has other plans and she is destined to marry Pakal’s youngest son in Lakam Ha (Palenque), and through this union to continue the dynasty.

The Prophetic Mayan Queen: K’inuuw Mat of Palenque, Book 4 by Leonide Martin (expected publication date summer 2016)

Buy Books 1, 2 & 3 at my Amazon Author Page

Lennie's Blog

- Leonide Martin's profile

- 142 followers