Gregory Crouch's Blog, page 34

May 15, 2012

Evacuating Shanghai, August 1937

To maintain narrative momentum and keep focused on the story’s main character, William Langhorn Bond, I excised most of the details of CNAC’s evacuation of Shanghai from China’s Wings chapter 8, “Things Fall Apart,” which happens in mid-August, 1937 at the beginning of the Battle of Shanghai.

A couple of really amazing and adventurous anecdotes were contained within, however — particularly the ones based one my interviews of Moon Chin and the diary entries and correspondence given to me by Nancy Allison Wright, Ernie Allison’s daughter — and I’m going to work them into my next few China’s Wings posts here on my website.

Chapei on fire north of the International Settlement, August 1937

We begin at Shanghai’s Lunghwa Airport on August 15, 1937, with Shanghai erupting into flames north of Soochow Creek, some 6 or 8 miles north of the airport, as fighting broke out between Japanese and Chinese forces.

One of CNAC's Stinson Detroiters

American Royal Leonard, the Generalissimo’s personal pilot, flew one of CNAC’s DC-2s from Shanghai to Hankow for $1,000 Chinese dollars. Frank Havelick took another. Floyd Nelson flew the third under protest.[i] He’d flown 260 hours in the last two months and was sick from exhaustion. CNAC operations called Moon Chin and ordered him to the airport. Moon left his wife in their French Concession apartment. Allison’s evacuation was underway when he reached Lunghwa. Donald Wong, Moon’s best friend, was outbound for Nanking in one of the airline’s two Ford tri-motors. Hal Sweet and Bob Pottschmidt each had a Stinson in the air behind Wong. Allison assigned Moon Chin to follow in a third Stinson.[ii]

Street fighting in Shanghai

Moon winged up from Lunghwa and raced west, away from the city. Behind him, downtown, he glimpsed the Japanese warships clogging the Whangpoo’s Pootung bend and the whiffs of smoke wind-blown from the muzzles of their guns as they belched cannon fire point-blank into the fighting into the fighting. Brutal, awful, close-quarters melees raged in the dense neighborhoods north of the International Settlement. Driven by the strong winds, smoke whipped sideways from battlefield infernos in Chapei, Hongkew, and Yangtzepoo. Japanese war planes swooped and dove over targets around North Station.

Warships in the Whangpoo

West of the city, Moon Chin arced northwestward and set course for Nanking. He had no idea when, how, or if he’d be able to return to Shanghai. He hoped his wife would be safe behind him. Moon cruised toward China’s capital at 125 miles per hour with his wings skimming the base of the cloud layer, quick shelter should he encounter Japanese planes. Moon Chin found two of the company’s Stinsons and the Ford tri-motor on the ground ahead of him in Nanking. He joined the other pilots at the Metropolitan Hotel and awaited instructions.[iv]

Here are forty pictures taken during the Shanghai fighting.

[i] Leonard, Havelick, and Nelson flew DC-2s from Lunghwa to Hankow: Manila Bulletin, August 29, 1937, clipping provided to the author via email by Ernie Allison’s daughter, Nancy Allison Wright, November, 2005.

[ii] Moon Chin’s experience evacuating Shanghai: author’s interviews with Moon Chin, September 17, 2004, January 7, 2005, April 19, 2006.

[iii] Ground combat: New York Times, August 15, 1937.

[iv] Moon Chin’s flight from Shanghai on August 14: author’s interviews with Moon Chin, September 17, 2004; January 7, 2005; April 19, 2006; “Bob Pottschmidt,” a summary of his personal history written in the late 1980s posted online at cnac.org (I suspect Pottschmidt runs two days together into one. The air raid Potty describes in Nanking occurred on August 15.)

May 13, 2012

An excellent old Shanghai photo collection

A fellow who seems to be named LJ Chan has posted a very atmospheric stream of old Shanghai photos… enjoy!

May 1, 2012

“Goddamn it, I promised the wife I wouldn’t do this any more.”

Eu Gardens, Hong Kong, 1938

Few people in the Colony had larger disposable incomes than CNAC’s Caucasian pilots, and few had more “face” in both Western and Chinese communities. They were admired by all strata of Hong Kong society, although perhaps not so much liked by the upper crust British as tolerated with a grudging nod to their courage and competence and in recognition of the valuable service they provided. Most of the Caucasian pilots lived Kowloon-side in the “Eu Gardens” at 158 Argyle Street, modern apartments reminiscent of those found in Southern California and built to the maximum residential height allowed in Kowloon – thirty-two feet.

Sylvia Wylie and Chuck Sharp in 1938

In lieu of gibbons, Chuck Sharp satisfied his pet-owning urge by acquiring a pair of dachshunds. He had a serious girlfriend, Sylvia Wylie. He bought a sail boat, and he and his pals spent off-duty days skimming the aquamarine waters of Hong Kong and exploring the bays and inlets of the surrounding islands. They ate elaborate lunches packed by their serving staffs and swam with their wives and girlfriends at an isolated beach seven miles from Kowloon where the pilots rented a weekend bungalow. Robert Pottschmidt was an avid amateur photographer who captured images of shirtless men leaning against the rail and propping their feet on the hatchways of Sharp’s sailboat and smiling at happy looking women in bathing costumes and holding drinks. Off-cuty, the men sailed, shot birds, indulged hobbies, and played baseball and tennis, but their talk always drifted back to airplanes. Their wives played bridge and mah-jongg, gave each other fancy tiffins, teas, and garden parties and poured over the latest fashion news from New York. They shopped in the Colony’s smartest shops and wore sundresses and fancy hats to high tea in the sumptuous lobby of the Peninsula Hotel. The men wore tropical whites in hot weather and shirt sleeves and open collars for sport, but more often than not, they buttoned their shirts and wore gray or pinstriped suits, waistcoats, pocket watches, and silk ties, which they seldom loosened, even at informal parties held among themselves. In the years between the Battle of Shanghai and Pearl Harbor, Hong Kong was a wonderful place for westerners with money.

Chungking in 1938

Diversions weren’t so lively when the pilots overnighted in Chungking. None of Shanghai’s frenzied glamour had migrated upriver to the wartime capital. It was phenomenally dull. Whenever they could, the Caucasian pilots stayed in the Standard Oil Company compound on the South Bank, across from the city, but Socony’s rooms often filled with other itinerant visitors, which relegated the CNAC overflow to a grimy, rat-infested three-story hotel called the Shu Teh Gunza. Forced into residence, the men enlivened the dark, dull, interminable Shu Teh Gunza evenings with games of poker, craps, and bridge. Gambling didn’t always suffice. The men obtained variety by poking their head out of the establishment’s door and yelling for Joe, the Number One houseboy. Invariably, they ordered him to summon girls.

Happily, the Shu The Gunza was located adjacent to a whorehouse. It was a chicken or the egg conundrum as to who had arrived first, the pilots or the prostitutes. Houseboy Joe never needed more than a few minutes to appear with five or ten peasant girls in tow. Joe ordered the girls to disrobe. Coarse vestments fell to the floor and the players looked up from their cards and watched the naked girls march a few circuits of the room. The girls were worn and unattractive, and after a few minutes of parade the pilots usually informed Houseboy Joe that none were acceptable. The pilots passed the hat for tattered bills and old coins, and each girl received one Chinese dollar, then worth about one American nickel at open market exchange rates. Houseboy Joe rushed off to summon a replacement phalanx. Woody never detected repetition, but he suspected that most were simply local women herded together by the promise of an effortless dollar. It being China, however, more extensive services were available, and the boys could buy them for pocket change. Mortal terror of the unkillable venereal diseases reputed to inhabit Chinese prostitutes kept Woody from motivating himself to action, but some of his comrades were much less discriminating.

“Goddamnit,” lamented one of Woody’s married peers as he pushed up from the card table one glum, lonely Chungking evening and gestured a girl toward an upstairs bedroom, “I promised the wife I wouldn’t do this anymore.”

[i] C.N.A.C.’s valuable service: Arthur N. Young to H.H. Kung, March 1, 1940, the Young Papers.

[ii] Eu Gardens: Gellhorn, Martha, “Flight into Peril,” Collier’s, May 31, 1941.

[iii] Life in Hong Kong; C.N.A.C. fashion observations: Photos of the Hong Kong years provided to the author by Shirley Wilke Mosley, daughter of C.N.A.C. chief mechanic Oscar C. Wilke, Nancy Allison Wright, daughter of Ernest Allison; photos in the Bond Papers and in Wings for an Embattled China; Hahn, Emily, China to Me, pp. 113-116; Woods, Hugh, “Pre-War Life in Shanghai and Hong Kong,” Wings Over Asia, Vol. IV, pp. 4-9, 27-33, 40-46; Gellhorn, Martha, “Flight into Peril,” Collier’s, May 31, 1941; Angle, Chrystal, Reflections of Chrystal, pp. 173-178.

[iv] Diversions at the Shu Teh Gunza hotel: Woods, Hugh, “Playtime in Chungking,” Wings Over Asia: Memories of C.N.A.C., Volume IV, pp. 25-26.

April 30, 2012

“All right… but Mickey, why a limey?”

Hal Sweet on the left. (With Sidney De Kantzow and Pop Kessler)

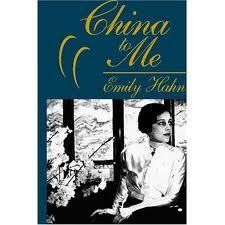

The last of the Emily “Mickey” Hahn outtakes from China’s Wings that I’ve been posting for the last week or so… (Start here and work your way forward.)

Like many of the CNAC pilots, Hal Sweet was friendly with Mickey Hahn. She and Charles Boxer had decided to get pregnant, and they’d succeeded, even though they weren’t married. Her and Charles Boxer hadn’t made any announcement, but the the whole world must have noticed, because in the summer of 1941, Mickey’s condition was obvious. However, nobody had the gumption to mention the situation to her face.

Society’s tight lips became a joke between her and Charles Boxer. They decided to award a prize to the first person to mention the pregnancy – a box of chocolates if it was a woman, a box of cigars if male.

Mickey Hahn and Mr. Mills

Hal Sweet bumped into Mickey Hahn in a shop after the DC 2 ½ episode. He hemmed and hawed and invited her for a drink. She accepted.

Sweet cleared his throat a few times once they were seated.

“Ah… Mickey… have you been married lately?”

She explained to him that he’d just won a box of cigars.

Hal Sweet frowned at her swelling tummy, “All right… but Mickey, why a limey?”

Hal Sweet and the cigars: “All right, but Mickey, why a limey?”: Hahn, Emily, China to Me, pp. 255; Cuthbertson, Ken, Nobody Said Not to Go, pp. 214, citing a personal interview with Emily Hahn.

April 29, 2012

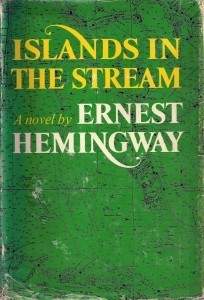

Ernest Hemingway and China’s Wings

As noted in yesterday’s “Boxer Uprising” post featuring Mickey Hahn, Hugh Woods, and Ernest Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway spent time with CNAC in late 1940 and early 1941, and he was so impressed with what the airline accomplished that he gave CNAC pilots a plug in his posthumous novel, Islands in the Stream, pp. 289, when the book’s main character, Thomas Hudson, is musing about the time he’d spent in Asia with “Hong Kong millionaires,” including “about six pilots for the Chinese National Aviation Company [sic], who were making fabulous money and earning all of it and more.”

As noted in yesterday’s “Boxer Uprising” post featuring Mickey Hahn, Hugh Woods, and Ernest Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway spent time with CNAC in late 1940 and early 1941, and he was so impressed with what the airline accomplished that he gave CNAC pilots a plug in his posthumous novel, Islands in the Stream, pp. 289, when the book’s main character, Thomas Hudson, is musing about the time he’d spent in Asia with “Hong Kong millionaires,” including “about six pilots for the Chinese National Aviation Company [sic], who were making fabulous money and earning all of it and more.”

I couldn’t fit the Hemingway anecdotes into China’s Wings, but it’s great to know that Ernest Hemingway admired the CNAC pilots as much as I do. My best guess as to the six pilots Hemingway was referring to is Hugh Woods, Chuck Sharp, Hal Sweet, Bob Pottschmidt, Billy MacDonald, and Frank Higgs.

I couldn’t fit the Hemingway anecdotes into China’s Wings, but it’s great to know that Ernest Hemingway admired the CNAC pilots as much as I do. My best guess as to the six pilots Hemingway was referring to is Hugh Woods, Chuck Sharp, Hal Sweet, Bob Pottschmidt, Billy MacDonald, and Frank Higgs.

April 28, 2012

Stephen Alvarez’s photos from our adventures in Iran last summer — climbing and otherwise

Stephen Alvarez’s photos from our adventures in Iran last summer, featuring Mark Wilford, Jim Donini, Mary Ann Dornfeld, Mohammad Norouzi, Mohammad Bahrevar, Shaima Shadman, Mahsa, Jenn Flemming, Chris Weidner, and others.

That was an intense trip.

Emily Hahn, Martha Gellhorn, Ernest Hemingway, China’s Wings, and The Boxer Uprising

I found a few more Mikey Hahn-flavored outtakes from the China’s Wings rough draft to add to the three-part story I told this week. Here’s one of them, which probably took place in January, 1941:

Emily “Mickey” Hahn didn’t return to the United States from Hong Kong. She stayed in the Colony and fell into a none-too clandestine affair with married British Army officer Charles Ralph Boxer. He worked in intelligence, and duty often called him to long hours. In her alone time, Mickey became friendly with CNAC’s Caucasian personnel and their wives, although as a writer without a financially successful book, she couldn’t keep the fast, fashionable pace maintained by the CNAC wives and girlfriends in anything except scandal, a Hong Kong niche she’d quite well cornered.

Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway, 1941

Other international notables fell into the extended social circle, including Martha Gellhorn, a groundbreaking female war correspondent who’d made her reputation reporting for Collier’s from the hottest combats of the Spanish Civil War and was a close personal friend of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Gellhorn had come to the Orient to write about the China war, and her nose for a good story led her straight to the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC). A gorgeous, long-legged blonde, Gellhorn had a new husband in tow, her second, and he was a renowned writer in his own right — Ernest Hemingway. Gellhorn, in turn, was Hemingway’s third wife, and he was basking in the smashingly successful release of For Whom the Bell Tolls, his novel of the Spanish Civil War. Gellhorn researched the airline; Hemingway pitched camp in “The Grips,” as the lobby bar of the Hong Kong Hotel was known throughout the Colony, and fell in tight with a crowd off-duty CNAC pilots and staff who often rendezvoused their after work to swill gimlets and exchange stories. One such gathering was picking up steam when a pilot noted Mickey Hahn’s absence. Hugh Woods wondered where she might be.

“She’s probably putting down a Boxer uprising,” retorted Hemingway.

The assembled fuelers erupted with laughter, and Woody could hardly wait to report the quip to the lady herself.

When he did, Mickey drew herself straight and peered at the cheeky pilot with regal Cleopatran scorn. “No one need have been concerned,” she pronounced. “You can assure Ernest that I had the situation well in hand.”

Although perhaps disappointed that such a scandalously delightful woman hadn’t fallen for one of the available aviators in their own crowd, the pilots took a measure of American pride in the fact that Mickey had poached the amorous attentions of a man who was clearly one of the more capable and intelligent officers in the British community. Mickey’s affair fared considerably more poorly in British circles, still stung by memories of King Edward the VIII’s abdication of the throne to marry “that dreadful woman,” American double divorcee Wallis Simpson.

Next, I’ll post the compliment Hemingway paid to the CNAC pilots in his posthumous novel, Islands in the Stream.

Hemingway and Gellhorn left the US in January, 1941, arrived in Hong Kong on February 22, and flew into the Chinese interior aboard one of CNAC.’s Condor freight planes on March 24: Moreira, Peter, Heminway on the China Front: his WWII Spy Mission with Martha Gellhorn, pp. 13-70; Lyttle, Richard B., Ernest Hemingway: The Life and the Legend, pp. 136-138; Bond, William L., Wings for an Embattled China, pp. 237-238. [Bond misplaces his Hemingway anecdotes in Wings. In Hong Kong, Gellhorn and Hemingway lived in the room at the Repulse Bay Hotel that had been vacated by Bond’s son, Langhorne and his nurse, Olga Chen.]

“The gimlet is the tipple of Hong Kong”: Hahn, Emily, China to Me, pp. 91.

The Boxer uprising: Woods, Hugh, “The Boxer Rebellion,” Wings Over Asia: Memories of C.N.A.C., Volume IV, pp. 30

A tone of fondness and approval color’s CNAC’s memories of Mickey Hahn: Hugh Woods anecdotes in Wings Over Asia: Memories of C.N.A.C., Volume IV; and in the cameo appearances she makes in Bond, William L., Wings for an Embattled China; author’s interview with Moon Chin, Frieda Chen and T.T. Chen, September 18, 2006.

That Mickey Hahn’s affair with Charles Boxer fared poorly in British circles, stung by Edward the VIII’s abdication: Cuthbertson, Ken, Nobody Said Not to Go, pp. 205.

April 26, 2012

Emily Hahn and CNAC, aka The Hardest Cut, Part III

This is the third part of this story, and they ought to be read in order. Here’s Part I and Part II.

The putrid ape smell didn’t fade from the apartment for weeks. Long before that happened, Woody learned Mickey Hahn was carrying on with Charles Boxer, a married major in the British Army. Woody had the good sense not to play the jilted fool. He and Mickey stayed friends, and Woody indeed felt guilty about reneging on his commitment to her pets. He retrieved them from the SPCA one Sunday afternoon and took them to Kai Tak airport for a change of scenery. A handful of airline employees were prowling around in the back of the hanger, where the British airport administration kept a full-service bar. Woody took a cocktail to a table with a few associates and anchored the apes to the leg of his chair with ten-foot chains. Sounds of American merriment attracted the airport manager, Mr. A. J. R. Moss, a lanky, angular Englishman wearing loose tropical shorts, a well-starched shirt, and high-pulled socks. The Americans thought him the prototypical British colonial officer, not a bad sort, just inefficient and officious. Moss inquired about the gibbons.

The putrid ape smell didn’t fade from the apartment for weeks. Long before that happened, Woody learned Mickey Hahn was carrying on with Charles Boxer, a married major in the British Army. Woody had the good sense not to play the jilted fool. He and Mickey stayed friends, and Woody indeed felt guilty about reneging on his commitment to her pets. He retrieved them from the SPCA one Sunday afternoon and took them to Kai Tak airport for a change of scenery. A handful of airline employees were prowling around in the back of the hanger, where the British airport administration kept a full-service bar. Woody took a cocktail to a table with a few associates and anchored the apes to the leg of his chair with ten-foot chains. Sounds of American merriment attracted the airport manager, Mr. A. J. R. Moss, a lanky, angular Englishman wearing loose tropical shorts, a well-starched shirt, and high-pulled socks. The Americans thought him the prototypical British colonial officer, not a bad sort, just inefficient and officious. Moss inquired about the gibbons.

Woods assured the Englishman he had the animals under control. Moss nodded and sidled to the table edge, tucked a swagger stick under his arm, and chatted with the seated Americans. Nobody noticed Mr. Mills, the larger of the gibbons, sneak behind Moss and peer up the Englishman’s shorts. Something he saw aroused his curiosity, and Mr. Mills reached a thin, hairy arm up Moss’ pant leg and wrapped his knotty fingers around the most prominent of the visible objects.

Moss howled. He would have leapt five feet in the air if the gibbon’s vice-like grip hadn’t anchored him so firmly to the ground. Woods and the other Americans hurtled off their seats, startled by the blood-curdling yell. Woody’s leap knocked over his chair, and the apes’ chains came free. The animals fled up the hanger girders and sheltered on the crossbeams under the rooftop, each terrified animal dangling a ten-foot chain. The Americans flopped around on the hanger floor, paralyzed with mirth and Moss’ pained embarrassment, eventually bestirring themselves to recapture the gibbons.

Woody never again dared take them out in public.

Mr. Mills was an older gibbon. He died sometime later, apparently due to complications caused by large open sores festering around his private parts. Mickey Hahn told Woody that although she couldn’t offer a professional medical opinion, she was convinced he’d died of syphilis.

Emily Hahn description: Hahn, Emily, China to Me; Ibid., No Hurry to Get Home; Cuthbertson, Ken, Nobody Said Not to Go, (a biography of Emily Hahn); Angell, Roger, “Postscript: Ms. Ulysses: Emily Hahn’s lifetime of reporting and vivid adventure kept her happily out of touch with convention,” The New Yorker, March 10, 1997;

Mickey Hahn, Hugh Woods, Chuck Sharp, and the gibbons: Woods, Hugh, “Gibbons,” Wings Over Asia: Memories of CNAC, Vol. IV, pp. 31-33; Hahn, Emily, China to Me, pp. 153-154, 205, 210, 235-237, (“noisily airsick”; “commenting on the shakiness of the plane”) It’s trivial, and in no way undermines the essential truth of her account, but in Emily Hahn’s China to Me, she flew from Chungking to Hong Kong on a CNAC flight piloted by Hugh Woods and with “the manager” (Bond) in the passenger cabin in late February, 1940 [using Cuthbertson, Ken, Nobody Said Not to Go, pp. 177-207, to help pinpoint the dates]. That is unlikely: both Bond and Woods were in the United States in February, 1940. After a brief Hong Kong sojourn, Hahn returned to Chungking and spent the bombing season in the wartime capital. She finished her Soong Sisters manuscript in July and again flew back to Hong Kong. Both Woody and Bond were in the Orient in the summer of 1940. I suspect Emily Hahn misordered her episodes with Woody, CNAC, and the gibbons when she wrote China to Me from the vantage of 1944, and that the February flight she described as making with Hugh Woods actually occurred in July. That timeline also puts the event into accord with Woody’s “Gibbons” anecdote in Wings Over Asia: Memories of CNAC, Vol IV. Woods was in the Orient in July, again flying for CNAC, and according to Woody’s account of his flight with Mickey, gibbons were discussed. There are other tidbits of circumstantial evidence that lend credence to the July scenario: Emily Hahn reports being driven to the Chungking airfield prior to departure. CNAC was using Sanhupah Airport on the sandbar below Chungking in February, which wasn’t accessible by car. However, in July, 1940, Sanhupah was flooded, and the airline was using a military airfield 12 miles from town. Passengers boated to the military airfield, except for lucky ones with access to government gasoline rations. Mickey managed to get herself driven by Fenn Lynch. Mickey Hahn wrote China to Me from memory in 1944, without access to her papers, which she’d lost in Hong Kong. (She and her daughter were repatriated in a prisoner exchange.) Such a minor error seems easy to have made, and doesn’t affect the truth of her exceptional tale. (And for the record, I count myself as the latest in a long line of men who’ve fallen in love with Emily Hahn; I also admit the possibility that I’ve made a reasoning error in reconstructing the sequence of these events, although it’s probably not materially crucial to my story, either.); careful aficionados of China to Me will also note that Emily Hahn doesn’t mention any period of time in which the apes were actually in Woody’s custody. Woody’s account is significantly different, and, I suspect, accurate. Mickey Hahn was busy falling in love in the days and weeks after her arrival in Hong Kong – with married British Major Charles Boxer, not, alas, with Hugh Leslie Woods.

The DC-3’s cockpit: author’s tour of a C-47 cockpit at the Strategic Air Command Museum in Omaha, Nebraska with CNAC pilot captain Donald McBride, October 6, 2004; “Operating Instructions for the Douglas Transport Aircraft Airplane Model DC-3,” Douglas Aircraft Company, Inc., Santa Monica, CA, 1942, PAA, Box 437, Folder 13

Mickey Hahn was just his type: the woman Woody married looked very similar to Mickey; The Big Smoke, Emily Hahn’s short story about her opium addiction, is a neglected classic.

April 25, 2012

Emily Hahn and CNAC, aka The Hardest Cut, Part II

Mickey Hahn and Mr. Mills

On the ground, Mickey Hahn crossed the harbor and took a room at the Gloucester Hotel on Peddar Street in Central Hong Kong, bought two new dresses, and reveled in the abundant hot water steaming in her private bathtub, a welcome change after months in squalid Chungking. A few days later, she called Hugh Woods to announce the gibbons’ arrival. Woody might still have been hopeful. If he was, he hadn’t yet realized flying glamour wasn’t sufficient to hold the interest of a woman like Mickey Hahn, but hopeful or not, Woody was still a-bother about gibbons, and they rendezvoused harborside. Woods hired a walla-walla sampan, so called because it took so much walla-walla, talk, meaning haggling, to settle on a price, and they motored out to the anchored steamship. They were late. Most passengers had gone ashore.

Mickey spotted a lady pacing the steamer’s side. Mickey steadied herself in the bow and flapped an arm. The woman stood to the rail. “Are you Mickey Hahn?” she yelled.

“Yes!” bellowed Mickey.

The woman slumped in visible relief.

The apes’ cage sat on the afterdeck. Mickey knelt before it. Her beloved gibbons stared at her without recognition. “Mills. Mills, old boy,” she said.

Mickey and her two gibbons in 1938, apparently from the Sinmay Zao family archive

Her voice triggered simian recollection. Mr. Mills came forward and snuggled into her arms. Mickey closed her eyes and held him close. The relaxed and happy gibbon defecated on her clothes.

Apes and humans repaired to Woody’s apartment. Mickey issued instructions and left to bathe and change clothes. The primates lurked in their cage, eyeing Woods and their new surroundings. Time passed. The gibbons seemed calm. Woody judged it safe to free them, a titanic mistake. The beasts sprang from the cage and tore around the apartment in a rage of uncorked primal energy, toppling chairs. One ape yanked off the table cloth. Plates and bowls shattered on the floor. The other heaved decorations and picture frames from the mantel. Woods raised his voice, something he almost never did, another epic blunder. His ire further incited simian riot. They whirled about the room, excreting a steady protest of soft stools. Woody chased them in a rage. The panicked animals covered the curtains, rugs, chairs, tables, and walls in sloppy offal.

Eu Gardens, where Woods and Sharp had their apartment

He finally caught and caged the gibbons, needing all the self-control he’d learned in thirteen years of professional flying to refrain from killing the miscreant beasts.

He called Mickey and informed her they were going to the Kowloon SPCA.

(Part III coming tomorrow…)

April 24, 2012

Emily Hahn and CNAC, aka The Hardest Cut, Part I

China’s Wings’ original manuscript was way too long. I spent most of the 18 months prior to publication trimming it into something readable, but due to their being “too far off the spine,” I gave the chop to many of my favorite scenes. The one that follows was the hardest cut of them all. I took it out and put it back several times before eventually deciding to let it go. But damn, it’s a good scene, and a funny one… it’ll take a few posts to tell, but here goes. Part one of three….

Hugh Woods

Square-jawed Hugh Woods had a flight from Chungking to Hong Kong scheduled one afternoon, and he particularly expected to enjoy it, for on the passenger manifest was Emily “Mickey” Hahn, The New Yorker’s far eastern correspondent. Woody wasn’t acquainted with her from their mutual Shanghai years, but he certainly knew of her, for Mickey Hahn was, without rival, the most notorious American woman in the Far East. She poached married men without scruples, and she’d stayed in Shanghai through the 1937 fighting, at the end of the battle becoming the Number Two wife of her Chinese lover, poet Zau Sinmay, in order to exploit a loophole in Japanese reasoning that allowed her to rescue the Zau family’s priceless Ming Dynasty library from the wreckage of their home north of Soochow Creek. Mickey joined Zau’s circle of opium users, and her addiction to “the big smoke” deepened through 1938. She landed a contract to write a book about the three famous Soong sisters in 1939, and the magnitude of the looming authorial task motivated her to take the cure. (“The Big Smoke,” Hahn’s short story about opium, is a neglected classic.) Painfully rehabilitated, she’d traveled to Hong Kong and thence to Chungking, interviewing her principals and their associates. She’d stayed in Chungking through the spring and summer and finished her manuscript under the rain of bombs. It was with the precious pages tucked among her belongings that she made ready to leave Chungking.

Mickey Hahn

A friend drove her twelve miles to the military airport and introduced her to Hugh Woods and William Bond, who was also traveling aboard. Quiet Woody had a weakness for cute, perky brunettes, and physically, Mickey Hahn was just his type. Being a pilot, Woods probably felt himself hopeful as he climbed the Douglas out of the bomb-battered city. He hit turbulence at cruising altitude. When the air smoothed, Woody summoned Miss Hahn to the cockpit, ordered his copilot aft, and slipped her into the vacated seat. A bewildering array of buttons, switches, dials, indicators, levers, lights, controls, and pedals crammed the cockpit. Woody broke the ice with a quick flying lesson. He kept the rudder pedals himself and gave Mickey the yoke, and she flew the plane, thrilled, and feeling important, although even with Woody’s patient tutelage, her unpracticed hand porpoised the sleek Douglas through the Chinese sky like a breathing cetacean – up-down, up-down, up-down. Riding in the back with a planeload of “noisily airsick” Chinese civilians, Bond scribbled a note to the cockpit commenting on “the shakiness of the plane since Miss Hahn took over.”

Woody retook the yoke, smiling, but he kept witty and vivacious Mickey in the right-hand seat. He held the plane on course without effort, ten thousand hours of experience handling the plane with unconscious mind. Mickey was a lively storyteller with a knack for fobbing off extraordinary occurrences as common and normal. Her oval countenance peeled into bright smiles, and mischievous glances flashed from dark, green-dappled eyes. Night fell. Woody felt better when darkness wrapped the plane, and they cruised through the night over a carpet of clouds, safe above the Japanese occupation. Mickey was at loose ends, planning to knot up the threads of her life and return to the United States. Her paramount worry was finding a home for the two pet gibbons she’d left in Shanghai. An Australian lady was escorting them to Hong Kong on a steamship. Chuck Sharp had once mentioned wanting one as a pet.

Woody immediately volunteered their apartment.

I’ll continue the episode tomorrow. In the meantime, here’s an interesting article about Micky and Zau Sinmay at China Heritage Quarterly, here’s her obituary in The New York Times, and here’s Roger Angell’s excellent “Postscript” in The New Yorker (only subscribers get access to the full text, I’m afraid). Here’s a piece on Hahn’s love affair with Zau Sinmay. Here’s a translation of one of Zau’s poems.

And here’s the second part of this story.