Gregory Crouch's Blog, page 33

May 30, 2012

A good climbing blog…

May 22, 2012

Taiping Diptych — two superb books on the most destructive war of the 19th Century

Ever heard more than a tidbit about the Taiping Rebellion, the civil war that convulsed China in the 1850s and 60s? I hadn’t either. It’s virtually unknown in the West, but it nearly destroyed China’s Qing (Manchu) Dynasty. The civil war sprung from the religious visions of Hong Xiuquan, a failed Confuscian scholar who, through a series of dreams and revelations, became convinced that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ. Hong and his core of original converts founded a Bible-based quasi-Christian religious sect and “The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom” and aimed at overthrowing China’s Qing Dynasty. The ensuing war between the Taiping and the Qing devastated enormous swaths of the Yangtze Valley — perhaps killing as many as 20 million people.

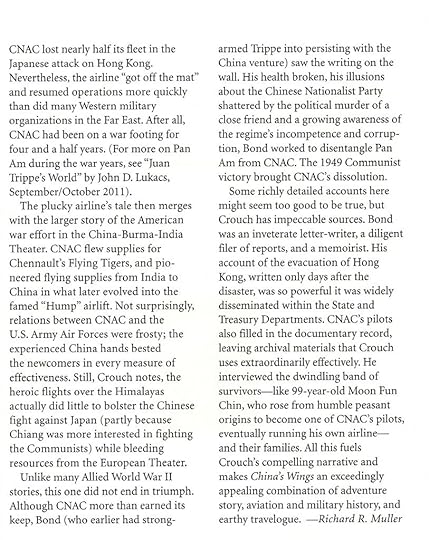

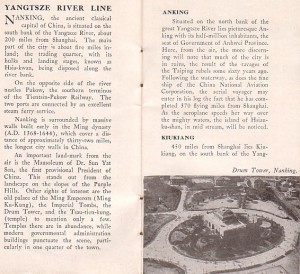

I’d seen the Taiping Rebellion mentioned a time or two in passing before I started researching China’s Wings, but never in depth, and never with more than a few details attached. During my research, I hit a Taiping reference in this CNAC travel brochure from the early 1930s and when I asked Moon Chin about it, he elaborated on the extensive wreckage behind the Anking waterfront. Those morsels put the Taiping Rebellion in my mind as something I’d like to know more about.

(Click on the text in the second image, and you’ll see that the brochure noting that much of the city of Anking was still in ruins, left over from the ravages of the Taiping Rebellion, sixty years before.)

(Click on the text in the second image, and you’ll see that the brochure noting that much of the city of Anking was still in ruins, left over from the ravages of the Taiping Rebellion, sixty years before.)

To that end. I’ve just finished reading the second of two superb books about the Taiping Rebellion. Taken together they make a excellent historical diptych — one written from each side of the rebellion.

First I read Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom, recently published by UMass Amhert professor Stephen R. Platt, and I couldn’t put the damn thing down. (Here’s its NY Times review.)

I found Platt on Twitter, and asked him for a recommendation for further reading on the rebellion, and Platt was good enough to come back to me with the suggestion that I read God’s Chinese Son by Jonathan D. Spence — which I finished last night.

Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom cleaves closest to the experiences of Hong Rengan on the Taiping side, Hong Xuiquan’s first convert, who at the climax of the civil war served as the “Shield King” of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (chief of staff and prime minister, essentially), and of Zeng Guofan, the brilliant Confuscian scholar, military commander, and statesman most responsible for suppressing the rebellion — and saving the Qing Dynasty. God’s Chinese Son spotlights Hong Xuiquan, the Taiping messiah. I strongly recommend them both. Platt fits the Taiping Rebellion into the larger tapestry of world events during the 1850s and ’60s and demonstrates how interdependent they were — how the civil war in the United States affected Britain’s China policy, for example.

(My only significant quibble with either of these books is with God’s Chinese Son, which Spence chose to write in the present tense, a quirk I found odd and distracting.)

I was struck by the similarity of the Taiping military campaign that led to their 1853 capture of Nanking and the Nationalist “Northern Expedition” of 1926-28. Presumably, both were governed by the military geography of Southern and Central China. Also, considering how close Hong Xuiquan came to toppling the Qing dynasty and installing himself in its place, it’s perhaps not so terribly surprising that an obscure revolutionary with profoundly rural roots would successfully accomplish a similar feat some 85 years later. And lastly, considering how close the Taipings came to toppling the Qing Dynasty and that they were essentially a spiritual movement (as was the Boxer Rebellion), is it surprising that the PRC keeps its heel so tightly stomped down on modern religious movements in The Middle Kingdom?

May 21, 2012

China’s Wings events in Santa Barbara and San Diego, June 2012

I have three China’s Wings events scheduled in quick succession on 10, 11, and 12 June, 2012.

I have three China’s Wings events scheduled in quick succession on 10, 11, and 12 June, 2012.

Santa Barbara, Sunday, June 10, 2012, 4:00 p.m.: I’m one of three authors serving on the non-fiction book panel at the Santa Barbara Writer’s Conference.

San Diego, Monday, June 11, 2012, 9 a.m.: San Diego Air and Space Museum, 9 a.m.: China’s Wings presentation and book signing for docents and volunteers.

San Diego, Tuesday, June 12, 2012, 6:30 p.m.: China’s Wings slide show and book signing at Bay Books at 1029 Orange Avenue, Coronado, CA 92118, 619.435.0070. Here’s the event page on the Bay Books’ website.

China’s Wings’ connection to Fedex…

… or why, every time you send a package via Federal Express, you’re connecting to the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC), China’s Wings, and the Hump Airlilft…

The connection comes through ten members of the American Volunteer Group (AVG), the real Flying Tigers, who joined CNAC after the AVG disbanded in July, 1942. (Bob Prescott (the front man), William “Bill” Bartling, Cliff Groh, Tommy Haywood, Robert “Duke” Hedman, C.H. “Link” Laughlin, Ernest “Bus” Loane, Robert “Catfish” Raine, Joe Rosbert, and Dick Rossi.)

1942-1945, they flew freight over the Himalayas for the China National Aviation Corporation, carrying many thousands of tons of war material from India to China.

Toward the end of the war, those ten ex-AVG, ex-CNAC pilots banded together, pooled their money, and formed an airline. Based in Los Angeles, they dedicated it to flying freight — a skill they’d learned flying the Hump for CNAC — but they leveraged their ex-fighter pilot cache by calling their airline The Flying Tiger Line.

Toward the end of the war, those ten ex-AVG, ex-CNAC pilots banded together, pooled their money, and formed an airline. Based in Los Angeles, they dedicated it to flying freight — a skill they’d learned flying the Hump for CNAC — but they leveraged their ex-fighter pilot cache by calling their airline The Flying Tiger Line.

Their endeavor was successful, and the Flying Tiger Line operated independently until the late 1980s, when the surviving founders sold their airline to Federal Express.

Which is why, whenever you send a package via fedex, you’ve touched the American Volunteer Group, the China National Aviation Corporation, and the Hump Airlift.

Joe Rosbert on the right, after his epic walk-out of the mountains

I’ve had the good fortune to meet and interview Rosbert, Raine, and Rossi. Sadly, in the last decade, all of them have passed on.

Joe Rosbert’s epic 47-day crawl and hobble to safety after crashing in the snowy Himalayas is one of the best survival stories I’ve ever heard — and one of the great episodes in China’s Wings.

May 19, 2012

How a bomb dropped in 1937 complicated my life, 2004-2012

Continued from this post about Ernie and Florence Allison at the outbreak of war in Shanghai, August 1937…

A flight of Japanese warplanes roared across the city and bombed Lunghwa and Huanjao airfields.[i]

A DC-2 in front of the CNAC hangar at Lunghwa Airport, 1937 -- before the outbreak of war

Fearing the worst, Ernie Allison rushed from the Grosvenor House to the airfield to inspect the damage. By some miracle, CNAC’s hangar had been only hit once — by an incendiary bomb that had fallen through the roof of Allison’s office and set fire to his desk. Hangar hands and volunteer fireman extinguished the blaze before it spread, but it destroyed Allison’s office and burned the company’s operational records to ash.[ii]

Of all the bombs that the Japanese dropped during the 1930s and 40s, it’s strange to reflect on how much that one incendiary affected my life more than sixty-five years later — I would have saved colossal amounts of time during the years of my China’s Wings research (2004-2008), if I’d have had access to those lost records.

Eurasia, CNAC’s chief commercial rival, wasn’t so lucky — bombs shattered their hangar.

[i] Bombing of Lunghwa and Huangjao, Monday, August 16: “Chinese Surprised,” New York Times, August 16, 1937.

[ii] Incendiary bomb hits Allie’s office: Churchill, Edward, “The Rise and Fall of China’s Airlines,” clipping from an unidentified magazine, possibly a house organ publication for Harlow Aviation, clipping provided to the author via email by Ernie Allison’s daughter, Nancy Allison Wright, November 15, 2005.

May 18, 2012

China’s Wings in the Huffington Post

Happy to see China’s Wings get such positive ink from Christine Negroni in the Huffington Post. (Her mention is about halfway down the page.)

Hope she has more to say about it when she’s finished. :-)

Ernie and Florence Allison in Shanghai at the outbreak of war

Ernie Allison

While Moon Chin and the others were escaping upriver (adventures I’ve recounted in recent posts), Ernie Allison and many of CNAC’s other personnel were still in Shanghai. Here are some of their experiences:

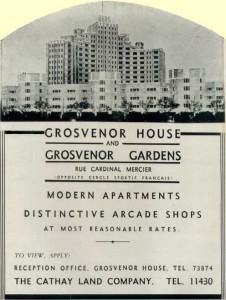

The Grovernor House, Shanghai

In Shanghai, Ernie Allison lived with his wife, Florence, in room 402 of the Grosvenor House, an eighteen-story apartment building next door to the Cathay Mansions and the French Club in the heart of the French Concession. They had a phenomenal view from their tenth floor veranda. Firelight flickered over the battlefields north of Soochow Creek all through the night of August 15-16, 1937, backlighting the Park Hotel and the Broadway Mansions. Booming artillery cannonades and the crackle of light caliber weapons sounded through their open bedroom window.

The Grovenor House

Florence lay awake in Allie’s arms, quivering. She was eight months pregnant, and she’d already lost several babies to miscarriages. Both Allisons badly wanted a child. If something happened to this one, so near term, Florence didn’t think she’d another opportunity. Finally, the sun rose. Their Chinese cook brought them waffles at 8:30 a.m. Chinese and Japanese warplanes took to the skies. Allie grabbed his binoculars and dashed to the veranda to watch the dogfights. Florence begged him to come inside, but Allie couldn’t tear himself from the action. A tremendous explosion shook the building. Florence leapt from her chair and ran into the living room, shaking from head to toe. Allie scurried back inside, “It’s nothing to be alarmed about,” he soothed.

Allie sat down, scarfed his waffles, and told his wife that he was going downstairs. Florence didn’t think he had any reason to do so. She asked their houseboy where the shell had hit. “Middle entrance,” he said.

Florence insisted on being taken to look. A stray anti-aircraft shell had blasted a divot in the driveway. A piece of shrapnel had sliced through a parked car. Looking up at the building, the Allisons saw shattered windows on all the floors from three to nine, and again in a row on the twelfth.[i]

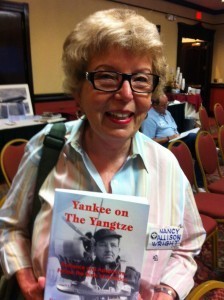

Nancy Allison Wright

[Florence's pregnancy ended well. Here's a picture of their delightful daughter, Nancy Allison Wright, holding a copy of Yankee On The Yangtze, a book she wrote about her father's pioneering aviation career. Nancy was incredibly helpful to me through the process of researching and writing China's Wings.]

[i] Florence Allison diary: Monday, August 16, 1937, entry provided to the author via email by her daughter, Nancy Allison Wright, November 15, 2005.

May 17, 2012

Moon Chin’s first air raid, part II

Continued from yesterday… another one of China’s Wings’ outtakes.

The bomber peeled from formation and banked toward them.

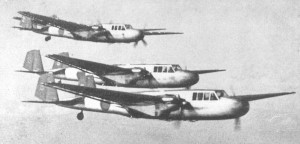

G3M Nells

It leveled out and bore toward them at two-hundred feet, targeting the Generalissimo’s hanger. Moon could see straight into the airplane’s plexiglas nose, where the bombardier sat, directing the attack. He was wearing a leather flying helmet.[ix] Three streaks fell from the plane. With his bombs loosed, the bombardier picked up the butt-end of the machine gun next to his bombsight, locked eyes with Moon Chin, and swiveled his machine gun toward Moon. Too late. The twin-engines howled overhead. Moon heard the chat-chat-chat of the machine gun further down the field. Then the bombs hit. One smacked through the roof of the Generalissimo’s hanger. Two black plumes spouted from the earth a few hundred feet in front of the bench. Moon Chin pressed his face into the dirt. The concussions boomed over him. He lifted his head and was surprised to see the Generalissimo’s hanger still intact. The last Japanese bomber disappeared into the cloud layer a few minutes after 3 p.m.[x] Moon Chin and Bob Pottschmidt stayed under the bench until the all-clear sounded five or ten minutes later.[xi] It was the first air raid Moon Chin or Pottschmidt had ever experienced. The most amazing thing was how fast it happened.

Japanese bomber (G3M Nell) over Sun Yat-sen's mausoleum outside Nanking

Moon and Pottschmidt inspected the two fresh craters in the dirt in front of the Generalissimo’s hanger. Inside, shards of splintered metal and sticky yellow dust – picric acid, an explosive compound – lay scattered on the floor. The bomb that hit the hanger was a dud. A hole in the roof, a smashed workbench, and a gouge in the concrete was the only damage inflicted.

Other engines sounded in the sky. Moon Chin rushed outside. It was Donald Wong’s Ford tri-motor at 460 feet, throttled back for landing. Moon wondered why he’d come back. Nervous anti-aircraft crews weren’t so quick with their aircraft recognition — they opened fire. A staccato row of machine gun bullets whacked into the aluminum fuselage and wings. Wong poured on the power and climbed into the clouds. Some minutes later, after the gun crews had been restrained, Wong bounced down onto the field, unharmed, but livid. He taxied to the C.N.A.C. station and cut the motors. Ten bullet holes perforated his airplane. Fortunately, none had punctured a gas tank, but one bullet had smacked through the cockpit and deflected from the front-left support of the copilot’s seat.[xii]

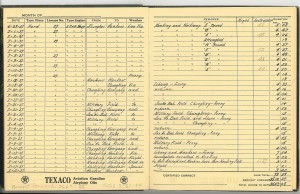

Donald Wong's pilot log. Note his entry for 8-16-37

Wong had escaped Nanking about five minutes before the raid began. He flew west and climbed into the clouds. Ten minutes out his radio failed. Without communication, he couldn’t track the progress of the raid, nor could he receive situation or weather reports from Hankow. He’d eased back under the cloud layer and returned to Nanking.[xiii] Hal Sweet must have continued to Hankow alone.

Moon Chin, Donald Wong, and Bob Pottschmidt flew to Hankow as soon as they’d checked Wong’s Ford.[xiv]

G3M Nell showing plexiglass in the nose

[ix]The planes that made the attack were the G3M “Nell” type. Most technical drawings of Nells show the plane with a solid nose, but I’ve seen a few photographs that show Nell’s with a Plexiglas bombardier’s station in the nose.

[x] End of raid: Lieutenant Commander Hiramoto, Michitaka, “Air Raid on Nanking,” The Chinese Mercury, Winter, 1938; basic details of Moon Chin’s recollections confirmed by a telephone interview with Nelson T. Johnson, the US Ambassador: “Chinese Fight Foe in Air at Nanking,” New York Times, August 16, 1937.

[xi] Five or ten minutes: author’s interview with Moon Chin, April 19, 2006.

[xii] Details of Wong’s approach and the damage to his airplane: Telegram, Wong to Allison, August 15, 1937, provided to the author via email by Allison’s daughter, Nancy Allison Wright, November 15, 2005; author’s interviews with Moon Chin, September 17, 2004, January 7, 2005. (Moon Chin said there were a dozen holes in Wong’s airplane; Wong’s telegram said ten.)

[xiii] Donald Wong flight: Bond to Kitsi, August 28, 1937, written in Hong Kong, the Bond Papers; author’s interviews with Moon Chin.

[xiv] Major details of Moon Chin’s experiences during the Nanking air raid confirmed: Pottschmidt, Bob, a summary of his personal history written in the late 1980s: http://C.N.A.C..org/pottschmidtletter..., accessed May, 2006.

May 16, 2012

Moon Chin’s first air raid, part I

This is the second part of this story, one of China’s Wings outtakes, describing what happened to the various CNAC pilots during the dark days of August, 1937, when a colossal battle between Japan and China erupted in Shanghai. Here is it’s beginning.

Moon Chin in the middle, Donald Wong on the right. (And Joy Thom in the middle.) In front of a Stinson Detroiter

During the night of Sunday, August 15, heavy wind and rain swept in from the China Sea and battered Shanghai.[i] The weather wasn’t so bad in Nanking, 180 miles inland. The city’s thick Ming Dynasty walls were thirty-miles in circumference, and they contained two airports, one civilian and one military.[ii] CNAC pilots Moon Chin, Donald Wong, Hal Sweet, and Bob Pottschmidt had spent the night in Nanking. Just as they sat down to the Metropolitan Hotel’s breakfast, airline operations summoned them to the commercial airport. All four hurried to the flight line without eating and were told to take off, right away, and follow Donald Wong’s Ford tri-motor to Hankow. The Ford was the only plane with a radio, and since the Stinsons couldn’t keep pace, Wong flew ahead and circled while the others caught up, and thus the formation inch-wormed west, up the Yangtze. Halfway to Hankow, the Ford U-turned and flew back east. Sweet, Pottschmidt, and Moon Chin assumed Wong had received new instructions. They dutifully followed in their little monoplanes, and Wong led them all the way back to Nanking.[iii]

Stinson Detroiter

Nobody in Nanking had any idea why they’d been recalled.[1] The hungry pilots left their planes with the ground crew and hustled back to the hotel to gobble lunch while the planes were serviced — every one of them had missed breakfast. Moon Chin pinched up a few morsels between the tips of his chopsticks. Two or three bites into his meal the air raid sirens wailed.[iv] The telephone rang and summoned the pilots back to the airfield with orders to get their airplanes away before the raid arrived. Moon Chin wolfed a few more bites and dashed after the others.

Ford Trimotor in Yunnan Province

Donald Wong’s “Tin Goose” tri-motored Ford and Hal Sweet’s Stinson were fueled. The two of them took off for Hankow. Bob Pottschmidt, a lean, blonde, twenty-six year old former track star from Winthrow High School in Cincinnati, Ohio,[v] was perched atop the wing of his Stinson, helping a coolie fuel the plane. “Potty” held a chamois across the mouth of a funnel with one hand and the fuel hose with the other. Below him, the blue-dungareed coolie frantically worked a hand pump threaded into the top of a 55-gallon fuel drum. Moon stood beside the tail, waiting his airplane’s turn. Soft drizzle leaked from gunmetal gray clouds, ceiling 500-feet.

Moon Chin heard a far-off rumble. Pottschmidt heard it, too: the drone of airplane radials. Three blurs appeared in the scrappy mists trailing from the cloud bottoms. The planes lost a few more feet of altitude and resolved into twin-engine monoplanes. “Those’re Jap bombers!” yelled Potty. “They’re gonna hit the other field!”[vi]

The flight dropped out of the clouds on perfect course to attack the flight line of the military airfield, about a mile from where the CNAC men serviced their planes. Black clouds of debris spat up from the earth. The roof of an immense hanger leapt into the air atop a yellow-red pillar of flame.[vii] Torrents of anti-aircraft fire reached for the attacking planes. Moon Chin hadn’t seen bombs fall. A second later he heard the booming detonations.

Pottschmidt dropped the hose and leapt off the wing. Moon joined him in a sprint for the airport gate. The coolie kept pumping like mad. He was staring at the bombing and hadn’t noticed Potty’s jump. Gas squirted onto the ground and pooled around his feet before he yelped and ran after the others. The airport guards refused to let them leave. More bombs exploded on the nearby airfield. Moon and Pottschmidt ran to the passenger terminal, a solid construction. It was packed with frightened civilians. The Generalissimo’s personal hangar was beside the terminal. The two pilots ran to a concrete bench opposite and wriggled to shelter on the muddy ground beneath.

Other bombers dropped out of the cloud layer, every one perfectly lined up to pummel the military airfield. “That’s some damn fine navigation,” observed Pottschmidt.

“They’re getting help,” Moon stated.

Pottschmidt nodded. It couldn’t be done any other way. The Japanese had to be getting help from fifth columnists on the ground in Nanking. Flying from bases on the island of Formosa, far to the south, the bombers were probably homing in on the Nanking Radio Station, mouthpiece of the Kuomintang, which pushed the strongest signal in the city. It wasn’t Nanking Radio, however, that betrayed the presence of local assistance. The perfect short-range approach did that. Radio Nanking’s signal would get the bombers into the city’s vicinity. It wouldn’t get them to points of such phenomenal precision over the airfield. To do that, someone on the ground must have placed smaller transmitting beacons a mile or two on either side of the airfield, the exact axis of approach the bombers intended to use being the line drawn between the two transmitters. Close to Nanking, the bombers tuned their homing devices to the short-range beacons, then maneuvered until they had the two signals exactly aligned. Keeping the signals together, the planes flew towards them at a pre-planned altitude. The instant they passed over the first beacon (they’d know it had occurred when that signal’s direction flipped 180 degrees), they began their letdown through the clouds at a predetermined descent rate, continuing toward the second transmitter and therefore perfectly lined up with the target. They popped through the clouds at five or six hundred feet, in the middle of their bomb runs, just like they’d been making a foul weather instrument approach to the airfield, which was, of course, exactly what they had been doing. It was a very avant-garde aviation technique for 1937. There was no other possibility.[viii]

Suddenly, a Japanese bomber peeled from formation and banked in their direction.

Conclusion to follow tomorrow…

[i] Sunday’s weather: “Chinese Surprised,” New York Times, August 16, 1937.

[ii] Nanking’s Ming Dynasty walls contained two airports: Bixby, Harold M., Topside Rickshaw, Ch. X, pp. 58; Author interview with Moon Chin, September 17, 2004.

[iii] August 15 details and the Nanking air raid: author interviews with Moon Chin, September 17, 2004 and January 7, 2005; “Bob Pottschmidt,” a summary of his personal history written in the late 1980s and posted at cnac.org

[iv] “Chinese Fight Foe in the Air at Nanking; Report Downing 6 of 12 Attackers,” New York Times, August 16, 1937: “Japan’s first air attack on Nanking yesterday [August 15] undoubtedly as the highpoint of the day’s aviation activity.”; Chang, Iris, The Rape of Nanking, pp. 65; Imperial Japanese Navy Lieutenant Commander Hiramoto, Michitaka, “Air Raid on Nanking,” The Chinese Mercury, Winter 1938, confirms Moon Chin’s recollection that August 15, 1937 was the date of the first Japanese air attack on Nanking.

[v] a twenty-six year old former track star from Cincinnati, Ohio’s Winthrow High School: unidentified newspaper clipping posted at cnac.org.

[vi] Pottschmidt’s quote: author’s interview with Moon Chin, September 17, 2004 and January 7, 2005.

[vii] Hanger detonation: Lieutenant Commander Hiramoto, Michitaka, “Air Raid on Nanking,” The Chinese Mercury, Winter, 1938.

[viii] Details of this day: Author’s interview with Moon Chin, September 17, 2004, January 7, 2005; “Bob Pottschmidt,” C.N.A.C. Cannonball, January 15, 1989; Michitaka Hiramoto’s article “Air Raid on Nanking” confirms the poor weather (“a raging typhoon” and “the city lay under heavily banked clouds”) and that much planning went into the execution of this raid: “All the details of the expedition had been gone over carefully”; Moon Chin carefully described the precise Japanese navigation and its requirement for covert support to the author on multiple occasions.

May 15, 2012

China’s Wings reviewed in World War II magazine

I’m very pleased! In the about-to-be-released July/August issue of World War II magazine, aviation historian Richard R. Muller reviewed China’s Wings as “a first-rate saga of aviation, wartime politics, and business that manages to be gripping without sacrificing scholarly rigor,” a “compelling narrative,” and “an exceedingly appealing combination of adventure story, aviation and military history, and earthy travelogue.”