Matthew Dicks's Blog, page 379

September 19, 2014

There was a dead man in our hotel room.

Slate asks:

What protocol does a hotel follow when a guest is found dead?

Turns out I have a little bit of experience with this question.

When I was 23 years-old, my friend and I went on vacation to Myrtle Beach, South Caroline and Orlando, Florida. We drove south by car, stopping in Myrtle Beach for three days before proceeding to Orlando and Universal Studios. We were scheduled to stay in Florida for four days, but after two, we decided to head north and spend our last two days back at Myrtle Beach.

We liked it much better.

We drove all night from Florida to South Carolina and spent the morning sleeping on the beach. With our funds running low, we searched for a cheap room and found one over a liquor store less than a mile from the ocean. When the liquor store owner opened the door to the room, we saw the chalk outline of a person in the carpet in the center of the room.

“Haven’t had time to shampoo the rug,” the man said. “But he’s long gone.”

Since police don’t normally draw chalk outlines around heart attack or stroke victims, we assumed that the man had died via nefarious means.

Turns out that the chalk outline wasn’t so bad. The enormous cockroach that we found in the bathroom was far more terrifying.

September 18, 2014

September 17, 2014

Procrastination: Are the resulting lower grades really all that bad?

A new study suggests that students who turn in homework at the last minute get worse grades.

Of the 777 students involved, 86.1 percent waited until the last 24 hours to turn in work, earning an average score of 64.04, compared to early submitters’ average of 64.32 — roughly equivalent to a ‘B’ grade.

But the average score for the most part continued to drop by the hour, and those who turned in the assignment at the last minute had the lowest average grade of around 59, or around a C+.

It’s a bit of a no brainer and something that a reasonable person might have accurately assumed absent this research, but I think a more important question remains unanswered:

Are the procrastinators learning less?

I am a strong advocate of purposeful procrastination in all non-critical tasks. If I report is due to my boss on Friday, I will wait until the last possible moment to begin working on it, filling my time in between with more meaningful and enjoyable tasks. Being constantly concerned with the prospect of death, the last thing I want to do is spend my final day on Earth completing something mundane or ultimately unnecessary that I could’ve been done three days later.

Many think that factoring in the possibility of death into my to-do list is fairly insane, but those critics will die someday, and it will probably be on a crisp, September day that they spent sorting receipts for next year’s taxes.

As a purposeful procrastinator, I’m left wondering if the procrastinators in this study who are turning in work at the last moment and achieving slightly lower grades are actually learning less, or are their grades merely a reflection of a rushed effort that contains all of the learning required but less polish?

And if so, do these lower grades actually matter? If the procrastinators and the non-procrastinators are equal in their learning, do the slightly higher grades of the non-procrastinators yield a greater number of job offers? Higher starting salaries? More rapid advancement?

In most cases, I don’t think so.

I’d also love to see the differences in happiness between procrastinators and non-procrastinators. In my admittedly biased and anecdotal experience, the procrastinators of the world seem to be a more relaxed and less anxious group of people. They seem to handle stress and uncertainty better. They appear to be less concerned with the opinions of others. They are not the ardent people-pleasers that aggressive completionists tend to be.

Don’t get me wrong. All procrastination is not good. Allowing your laundry to reach the point that you must devote an entire day to it is probably not a good idea. Waiting until the last minute to write your novel will probably result in a poor effort. Forgoing your oil change for another 5,000 miles is not a wise decision.

But a fairly innocuous college assignment?

Maybe the slightly lower grade isn’t such a bad thing if you fill the time that you spend procrastinating with something that is meaningful or joyful or more valuable.

And perhaps the process of completing the assignment at the last minute has its benefits as well. By purposefully procrastinating, maybe a person learns to manage stress better. Focus more effectively. Handle uncertainty with greater deftness.

This is the kind of research that I would like to see.

September 16, 2014

The tyranny of the syllabus

I know a handful of college professors personally. I know a handful more via Facebook and Twitter. I have known many, many more throughout the years. Right around this time of the year, the discussions about their fabled syllabi begin to appear, both in real life and on social media.

Their comments can usually be boiled down into the following statements:

I am working on my syllabus.

I feel angst about my syllabus.

The work that I’m doing on my syllabus is complex and time consuming.

I am proud of the work that I have done on my syllabus.

As a teacher, I find this never-ending conversation about syllabi both amusing and disturbing.

Let’s start off with the dirty little secret of higher education:

Professors are not teachers. The great majority of them have almost no formal training and have never studied the art and science of teaching. They are experts in their specific fields of study, and if their students are lucky, they have received a modicum of training from the college or university where they teach (usually a week or two before the semester begins), but for the most part, they do not have any actual teaching certification, scholarship, or meaningful training.

This is not to say that their instruction is ineffective.

However, in many cases, it is highly ineffective. I have attended classes at six different institutions of higher learning, and I have met many professors who are experts in their field of study and utterly inept in the classroom.

Thankfully, I have also been taught by professors who are incredible teachers, too. For the most part, I suspect that these people possessed many of the innate qualities of an excellent teachers long before they entered the classroom. I also suspect that these professors have chosen to study the art and science of teaching with the same vigilance and rigor as they study in their field of expertise.

These people are teachers disguised as professors. They are highly effective, oftentimes inspiring, and sometimes life changing.

Unfortunately, they are too few in number.

Which bring me back to the syllabus:

The carefully designed plan for the entire semester. The source of both angst and pride of so many professors and students.

Also one of the most disastrous and ridiculous documents in the field of education.

The syllabus represents a professors plan for instruction for the course of approximately four months. It is disseminated to students at the beginning of the semester, and in most cases, it is adhered with rigor and fidelity. Due dates are predetermined and enforced. Readings are assigned and expected to be completed by the date indicated. Lectures and coursework is paced in accordance with the schedule set forth. Everything that students will be doing over the course of the semester is listed in clear, explicit language.

Ask a teacher to teach using a similar plan and he or she would laugh you right out of the classroom.

At its most fundamental level, teaching is a process that requires engaging instruction, ongoing assessment, constant differentiation, and relentless adjustment.

A syllabus is the antithesis of this. It represents uniformity. It dictates a predetermined pathway for instruction. It sets expectations that apply to all students, regardless of talent or ability. It predetermines precisely how long a group of learners will pursue a particular topic.

This is, of course, ludicrous. This is not teaching.

An example:

My hope may be to finish reading Macbeth with my fifth grade students by September 28. That is my plan, and I have communicated it to them (though being fifth graders, I’m sure that most don’t remember this). But if my students don’t understand certain concepts in the play or are incredibly enthusiastic about the text or ask unexpected and surprising questions or despise Lady Macbeth with every fiber of their being, that September 28 deadline could easily drift forward or backward.

I will assess understanding and enthusiasm and adjust accordingly.

This is the essence of good teaching.

I will also adjust my instruction based upon my students’ individual needs. I will seek to understand those differing levels of ability and differentiate instruction based upon my students’ specific skill levels.

Nothing is static. There is no four month plan, because there can be no four month plan. I work with human beings. Not widgets.

My plan is to study four Shakespearean plays before our winter break. That number may increase or decrease based upon any number of factors.

My students may be so thoroughly enthralled with tragedies that I decide to skip the comedies entirely. Or at least delay them until the spring.

A graphic novel of Macbeth may be released that I decide to add to our study. Or a film. Or a play at a local theater. Or a student-created puppet show.

Any number of factors will alter content.

This is what teaching is all about. Engaging instruction and relentless adjustment.

But this is how many, and perhaps most, college classes are typically taught. The syllabus determines the what and when.

In a college classroom, assessment rarely drives instruction. The syllabus drives instruction. Assessment is used for determining grades. It does not determine which students require additional instruction. It does not signal to professors that their students require additional time or increased levels of challenge in order to achieve their greatest academic potential.

“Greatest academic potential” is a state that all teachers seek for their students. But in order to achieve this state (or even strive towards it), a teacher must constantly monitor, assess, adjust, and differentiate.

I have almost never seen this process take place in a college classroom.

Rarely is work at a college level differentiated. Despite obvious differences in the backgrounds and abilities of students, instruction is delivered to all students at the same time in the same way.

In college, differentiation is not done in the classroom. It is not handled through instruction. It is parceled out in 15-30 minute chunks known as office hours.

To an actual teacher, this is insanity.

I believe that it’s this relentless march though the syllabus that has led to the rise of online learning and MOOCs. Rather than acting as teachers, professors have presented themselves as content delivery systems. They set forth a plan and adhere to it, lecturing, assigning grades, and marching through their semester regardless of circumstance.

You will read about Subject X before Monday. I will lecture about Subject X on Monday. We will engage in a class discussion. You will write a paper on Subject X, which is due the following Monday. I will assign you a numerical score based upon your adherence to a rubric that I have determined.

What about the student who struggled with the reading?

What about the student who was not challenged by the reading?

What about the class who does not find Subject X nearly as engrossing as you do?

What about the class that wants to spend another week discussing Subject X?

As a teacher and a former college student, I would like to see the college syllabus become more of an approximate plan for the semester, with fairly rigid timelines in place only in two week increments.

“Here is what we will be doing this week and next. It includes the readings and assignments. We’ll see how it goes. Then we’ll figure out the next two weeks. Because we are learners. Not robots.”

Teachers do not speak of their curriculum or lesson plans with nearly the same consternation or affection as a college professor does his or her syllabus because the teacher knows that curriculum and lesson plans are great until class begins. Then the real teaching starts.

As German general Helmuth Von Moltke said:

“No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.”

A majority of college professors do not subscribe to this belief. They encounter the enemy (their students) and march forward, regardless of obstacle or resistance.

Follow the syllabus. Administer the tests. Finish the semester. Ignore the wounded who litter the battlefield.

This is not teaching. It’s content delivery.

It’s a damn shame.

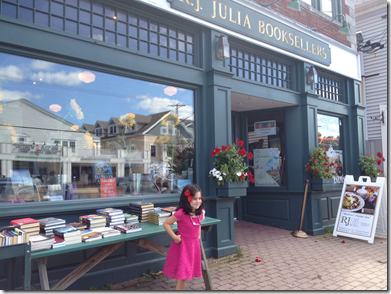

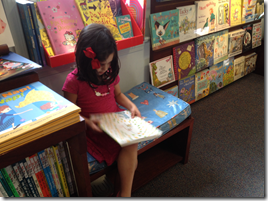

My children visited a bookstore on the last day of summer. Their behavior was shocking.

We spent the last day of summer on the Connecticut shoreline. Among our choice of activities was a visit to our favorite bookstore, R.J. Julia in Madison, Connecticut.

Elysha and I once spent hours in bookstores, but when our children entered our lives, that changed. We tried for a while to do some tag-team parenting. One parent relaxes while the other stops the monsters from ripping every book off the shelf.

It wasn’t fun.

But something happened on that last day of summer. I brought the kids upstairs to the children’s section of the bookstore, and within a minute, with no intervention on my part, this happened:

Not only did they plop themselves down and start reading, but they remained this way for a full 30 minutes.

Just imagine how much better it will be when they can actually read!

I probably couldn’t leave them unattended and descend to the adult section, but while my wife browsed below, I browsed the children’s section, which I sort of love anyway. I’ve written a few picture books that I am hoping to eventually sell, and I missed out on these books as a child, so I still have lots of catching up to do.

Even if this weren’t the case, this is a huge improvement over chasing them around, shushing them, and returning strewn books to the shelves.

This is good.

There is hope for the future.

September 15, 2014

My best piece of parenting advice

It takes a special and exceedingly wise breed of parent to ignore a temper tantrum like this and instead retrieve the camera and document the moment for posterity.

My wife is that kind of parent. She gets it.

I have a great deal of parenting advice to offer. Most people think that I am full of bluster and hubris. You probably do, too.

But I believe that my 16 years of teaching experience, in combination with my experience raising a former stepdaughter to the age of 16 and my two own children has given me wisdom that would prove valuable to anyone willing to listen.

Few admittedly do.

A colleague recently suggested to a parent that she ask me for advice on a childrearing issue. The person laughed. So did two other people at the table. The notion that I could have anything useful to offer was ludicrous in their minds.

Regardless, this photo of Charlie’s tantrum reminded me of my best piece of parenting advice that I have to offer:

Don’t become emotionally attached to your child’s poor decision making, regardless of their age. If your two year-old son is having a tantrum because he isn’t getting what he wants, that’s his deal. You can help him process his emotions and calm down, but the fact that he is having a tantrum should not impact you emotionally.

It’s not about you.

Instead, ignore the tantrum and take a photo. Capture the moment for future blackmail.

Just like his mom. And his dad, actually.

Our son, Charlie, spent the evening cooking dinner with Elysha. He spends most of this time demanding his mother’s attention and hanging on her legs, so involving him in the cooking was a great way to keep him from getting underfoot.

He loved it.

They made chicken nuggets, breading them in Cornflakes.

It occurred to me that as much as he reminded me of his mother while cooking alongside her, I have made my own share of chicken nuggets, too.

Tens of thousands of them, at least, during my tenure at McDonald’s.

His chicken nuggets were probably admittedly more nutritious than any chicken nugget I ever made.

September 14, 2014

If I was able to choose my children’s teachers, this is what I would want more than anything else.

If I were allowed to choose the teachers for my children, I would almost always choose the teachers with the greatest variation of life experience.

Give me a teacher who has dug ditches in Nicaragua, survived an encounter with a grizzly bear, panhandled across Europe, or spent ten years working in the private sector over a teacher who went from high school to college to graduate school to the classroom, absent catastrophe, epic struggle, or life-altering cataclysm.

This is not to say that the traditional path to teaching produces bad teachers. I know many outstanding teachers who have followed this traditional approach. I simply place more faith in a diversity of life experience and the perspective that it brings than I do in a stable life and a college education.

As Mark Twain famously said, “I never let school interfere with my education.”

Some of the very best teachers who I have ever known came to teaching from the most unorthodox and challenging routes imaginable.

These are the teachers who are confident enough to both take enormous risks and constantly ask for help.

These are the teachers who easily distinguish between what is important to learning and what is meaningless fluff.

These are the teachers who know which corners can be cut and which are critical to the success of their students.

These are the teachers who demand great things from their students and know how to shut their mouths and get out of the way in order to allow those students to exceed expectations.

These teachers tend to be unflappable, remarkably resilient, highly efficient, supremely independent, and beloved by their students.

In the words of one of my fictional characters, these are the teachers who teach school rather than play school.

High school to college to graduate school may transform you into a great teacher. But a diversity of life experience, a broad and varied perspective of the world, and a life of epic struggle, cataclysmic failure, and modest success is what I would look for first if choosing a teacher.

This is what I hope to find in my children’s teachers, far more than advanced degrees in education from the finest universities.

I thought this TED Talk demonstrated the importance and value of a diversity of perspective perfectly. It’s a stark reminder of how easy it is to assume that you and the people around you are the norm, especially when you and the people around you have always been you and the people around you.

When you choose the name Moxie Marlinspike, you have to expect people to ask about the name. Just answer the question.

I was listening to Moxie Marlinspike, an Internet security researcher, on the most recent episode of Planet Money.

Here is the exchange between Mr. Marlinspike and reporter Steve Henn:

Henn: Is that your real name?

Moxie Marlinspike: It is.

Henn: Was it on your birth certificate?

Moxie Marlinspike: No, it was not on my birth certificate, but it’s what almost everyone I have known has called me for most of my life.

Henn: What’s on your credit cards?

Moxie Marlinspike: Ah… which credit card?

Henn: You have a credit card with Moxie Marlinspike?

Moxie Marlinspike: Well, okay, I’m curious why you want to know?

Henn moves on (or edits out the rest of the exchange), but I’d like to answer Moxie’s question, because I want to know.

You see, Moxie, since you are an Internet security and privacy expert, I’m wondering if your apparent pseudonym is used to thwart the hackers who you spend so much of your life attempting to thwart.

It seems like pseudonyms might be relevant given your line of work.

If so, that’s interesting. I’m wondering if it’s effective.

If that’s not the reason (and I suspect that it’s not since your Wikipedia page lists two other names), I’d like to know why you changed your name to Moxie Marlinspike, because I think it says something about a man who chooses the name Moxie Marlinspike for himself, and it says even more when the man who chooses Moxie Marlinspike avoids answering questions about the origins of the name.

Few (if any) of those things are good.

Add to this the fact that you possess a master Mariner’s license and a love for the sea (facts I found on your own website), and the last name Marlinspike seems to take on even greater (but conveniently unmentioned) meaning.

In short, your obvious dodging of the name questions (not to mention your initial attempt to obfuscate the truth by indicating that it was your real name) leads me to believe that the story behind your name amounts to little more than a man who wanted a name that was cooler than the one his parents assigned but is uncomfortable admitting to this fact.

I could be wrong. There may be a damn good reason for the name. Maybe there’s an amusing (or less-than-amusing) story behind the name. If so, may I suggest you simply answer the question of whether or not your name is real with something like:

“It’s not my legal name, but it’s the name that I use, therefore it’s real. It’s a long and uninteresting story about how the name came to be.”

But the fact that you wouldn’t answer the reporter’s questions (and sounded fairly defensive while refusing), and the fact that the questions seemed fairly relevant considering the unusual nature of your made-up name and the fact that he was reporting on your company, which specializing in protecting your clients’ anonymity, leaves me to only assume the worst.

When I was nineteen, I told girls who I met while on vacation that my name was Gunner Nightwind, mostly because I was an immature douchebag.

I’m not saying that this is the case with you, but you haven’t given me much else to go on.

September 13, 2014

Men are far more likely to make stupid decisions in sports. But are the reasons for this stupidity all bad? I don’t think so.

This will come as no surprise to anyone who plays a coed sport:

On the playing field, men are more likely than women to make dumb decisions.

The major finding:

As the competition (in US Open Tennis) gets tighter, men are more likely to screw up. During set tiebreakers, female players were more likely to make the correct challenge call, and men more likely to make an incorrect call.

The study, conducted by conducted by economics professors from Deakin University in Melbourne and Sogang University in Seoul, only looks at US Open tennis, but the same principles are easily applied to other sports, including golf.

More than half of the errors that I make while playing golf are mental errors, and a good percentage of them amount to little more than dumb decisions.

These dumb decisions fall into three categories:

I failed to take an aspect of the course (a tiered green, an enormous pond, a stiff breeze) into account before swinging.

I failed to think strategically before swinging

I attempted a shot that was impossible or nearly impossible in hopes that it might work.

It’s this latter error (and my most frequent error) that this study seems to address.

Errors like these often occur when I am standing in a tree line on the edge of a fairway. “The mature shot” (a phrase my friends and I often use to describe the boring but sensible shot) would be to chip the ball out of the tree line onto the fairway and proceed to the green.

Instead, I look ahead to the green and see an opening through the tree line down to the green. Hitting my ball through this series of spaces between the trees will require me to hit a ball low and long and accurate to within three feet, absent of any slice or draw. It will require the perfect shot. But if I manage t pull it off, I could be on the green and save myself at least one stroke.

It’s a decision I make often. It’s a decision that my friends make often.

The results are rarely good.

These findings can be applied to other sports as well. I play coed basketball, and I’ve found that a man is much more likely to throw up an improbable shot during a game (and particularly near the end of the game) than a woman.

The authors attribute the propensity for men to make these kinds of dumb decisions to three factors:

Overconfidence: Men are more prone to cockiness, and think that their perspective is always correct.

Pride: Men also possess a disproportionate amount of pride. Governed by their egos, men can’t bear to lose, and are more susceptible to making an irrational decision.

Shame: Men are also less prone to shame than women. They don’t see the same downside to screwing up. “Guys just don’t care as much about losing challenges,” Martina Navratilova, winner of 18 Grand Slam singles titles, told TIME. “Women are more concerned about being embarrassed.”

The authors of the study agree:

“At crucial moments of the match, such as tiebreaks … male players try to win at all costs, while female players accept losing more gracefully.”

Overconfidence and pride seem to be hindrances to performance in almost all cases, but a reduced propensity for shame is less clear.

In the 16 years that I have spent working primarily with women, in addition to the three years spent studying at a women’s college, I have taken note in this difference in the way that men and women experience shame. I think Navratilova and the authors of the study are correct:

Men are far less concerned about being embarrassed than women.

While this lack of concern over embarrassment may lead to my willingness to attempt impossible golf shots and ultimately cause me to lose more often, I’ve also noted that men are more willing to take risks, both athletically and professionally, and that these risks often pay off enormously.

It also allows men to focus more closely on critical aspects of their job that they deem most important while allowing less important but potentially embarrassing aspects of the job to receive little or no attention.

It also prevents concern over perceived embarrassments over factors that others would never even notice.

This one seems especially prevalent in female culture.

So yes, men are more likely to make dumb decisions on the tennis court, and probably in most athletic endeavors. And yes, overconfidence, pride, and shame (or a lack thereof) are contributing factors to our stupidity.

But men’s reduced level of concern over embarrassment may not be all bad. At the very least, it reduces anxiety and worry and frees up vast amounts of time and resources. But it may also greatly contribute to a man’s willingness to try new things, take risks, fight relentlessly, fail often, and ultimately find higher ground.

And take some terrible golf shots along the way.