Michael Pronko's Blog, page 23

May 3, 2015

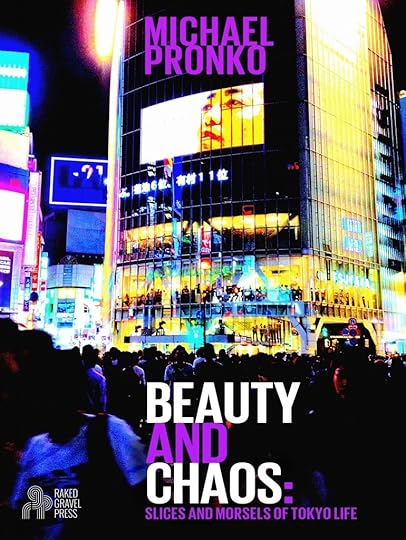

More reviews for Beauty and Chaos

“For readers interested in Japanese life and culture, or in simply reading a beautiful set of essays of a place you may or may never have been yourself, Beauty and Chaos is a spectacular read. Its essays are long enough to be cohesive and provocative while remaining short and sweet. The collection is masterful and unique.” – SPR Review

“Pronko’s topics are varied and surprising. He notices the kinds of things that might be taken for granted by the Japanese and overlooked entirely by visitors….These pieces feel flowing and natural, perhaps because many arose simply from walking around, people-watching.” –Rebecca Foster, The Bookbag

“A cleareyed but affectionate portrait of a city that reaches beyond simple stereotypes. An elegantly written, precisely observed portrait of a Japanese city and its culture.” Kirkus Reviews

April 25, 2015

Hanami, and Just After

After the clamor and crowd of hanami (cherry blossom viewing) has dissipated and people have eased back into their spring routines, everything changes under the blossoms, for the better.

It’s not that I don’t like hanami parties. I do. Sitting under a blazing white tree with good friends, not to mention thousands of others with their knee-to-knee circles of friends, is a kick. What’s not to like about workaday hassles set aside, worries, deadlines and obligations ignored, and sitting, eating, drinking, talking and looking around? Just resting your carcass on the solid earth for a couple hours resets your priorities, the mind-boggle of sharp-white, light-pink, dark-pink fluttering overhead. When a blossom falls in your cup, you just drink it down.

But I still like it better when the party’s over, after the drinking, clinking, hollering intensity of mass hanami partying is silenced, the trash is carted off, and you are alone with the cherry blossoms, looking up at them by yourself. Then, they evoke other feelings altogether.

The colors of the trees become subtler, and more varied, once the blare of white-pink is gone. On many trees, the fading pink and red mixes with the emerging green, creating, from a distance, a psychedelic glimmer. The red shifts to green shifts to red as the breeze jiggles the leaves. The red of some late-blooming sakura catches the light so strongly it smolders like neon.

The petals hang around, too. If the weather has been dry, the blossoms, light as cotton, blow into wind-catches, piling up in a corner, or sticking on the wet of a puddle. In front of my house, where I park my bike, the blossoms trapped by the wind create a royal carpet for a couple weeks, a good send-off every morning.

Then, my favorite part is when the little red things come. The sepals that enclose and protect the flower are dark, full red. They support the blossoms, holding them in place and prodding them to bloom. After the blossoms fall, these secondary red sepals tumble down in profusion. Their little red after-blossoms float down to layer a thick carpet of red on top of the quickly dissolving white.

The few days where the wind blows strong, the blossoms dance through the air. But later on, when gusts of wind still project a few late-falling blossoms, they become more rare and more precious. The early blossoms are for turning outward in socializing, but the later ones become a reminder of your inner world, and how beauty comes to you on unexpected gusts, if you can just pay attention.

Weeks after the peak of blossoming, I see smaller, spread-out groups of people hunkering down under the late blossoms for quieter parties. Groups of housewives with their children, nursery school teachers with kids in matching hats, and retirees in hiking costumes take over from the brash, go-to-it parties of the students and office workers.

I wonder if these groups love these late-blossoming trees the best, like I do. I guess they do, since the office workers are already tucked back into their cubicles, spreadsheets and emails, while we late-blossom-lovers are still outside digging the show.

One day last week, at sunset, I watched one group, all housewives with small kids and a circle of mama-chari (mother’s chariot) bikes. It was at dusk and they chatted amiably as they put away the plastic containers of food, recapped the pet bottles and folded up the tarp. They looked pretty pleased with themselves to have snuck in one last hanami party. Around them, all was green, except for this one last tree still freeing thick pink petals onto the ground.

And as they got everything packed to go and were about to ride away, the sun dipped under the horizon, and the rays, catching some fluke of atmosphere and cloud formation, turned the sky pink. It was too pink to ignore. They stopped and waahh-ed and looked around, as did I, amazed. They started fumbling to snap a cellphone photo with one hand, keeping the other on their kids plopped in their child seats.

All of us stopped and looked, the entire park bathed in pink, glowing pink, the earth seemingly holding the moment for us, until the color spectrum then slipped back to the typical orange-yellow-red of an average summer sunset, and it felt like the hanami season was, at last, over, sadly, expectedly, until next year.

Giveaway on Amazon

I’m giving away a few copies of my book, now out in paper format, and a few more e-books, too. Here’s the link to trying for a free paper copy on Amazon. Check it out!

https://giveaway.amazon.com/p/22e6fb3d817dc9b5

Hope you win!

March 22, 2015

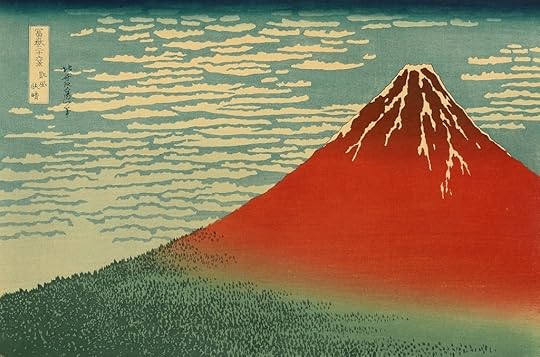

Seeing Fuji

From my backyard, officially, I can see Mount Fuji. The iconic volcano rising from the plains southwest of Tokyo and Yokohama, is a stunning site no matter where you stand. But when I say I can see it from my house, I draw jealous gasps of “Really?” from Tokyoites. Saying you can see Mount Fuji from your house is like saying you have a view of Central Park to New Yorkers or a view of the harbor to Hong Kong-ers.

Everyone knows where Fuji is. After all, it’s the most iconic image of Japan, coming in ahead of kimonos, chopsticks and sushi. Because of the low plains surrounding it, Mount Fuji is visible from very far distances, even as a small bump on the horizon it is instantly recognizable.

Everyone in the Tokyo area usually has a feeling for just where Mount Fuji is, like Muslims always know in which direction Mecca lies. Many people can catch the occasional glimpse of Fuji from where they pass by a break in apartment complexes, a window in an office walkway, or a small hill or elevated bridge.

But those are just quick peeks. It’s hard to find a place in Tokyo or Yokohama where you can sit down to leisurely contemplate the setting sun throwing the elegant curves into evening relief. If it were an everyday thing, maybe there would be more contemporary poems and paintings of Fuji. As it is, Fuji is confined now to color illustrations, ersatz woodblock print images, or fixed-up high-res photos.

To see Fuji from my house, I can’t just stroll out onto my back porch. I have to lean over the edge of the balcony, or hoist my butt up on the rickety cinderblock garden wall, and stretch my neck. Recently, a repair project on the power lines meant cutting down a bunch of trees. The lines went back up, but the trees stayed down. So now, I don’t have to lean quite so far to catch a glimpse.

That view, even leaning and stretching for it, always packs a “wow.” Set alone across the plains of Kanto, Mount Fuji is a unique bit of geography that rises up majestically, like a question to ponder.

I can see a bit better from around the corner, where a sliver of a hillside park offers a bench with a little note about this being yet another “Fujimi” spot. “Fujimi” translates as “place to see Mount Fuji,” and all around the Tokyo, Yokohama and Kanto region, there must be thousands, even millions, of Fujimi Roads, Fujimi Parks, Fujimi Hills, Fujimi Resorts, Fujimi Apartments. Stores, restaurants, product brands and people are all named “Fuji.”

That little moniker boosts not just the prestige, but also the price of whatever it attaches to. Many of those places still have an actual view of Mount Fuji that has not been blocked by building developments. Tokyo and Yokohama sprang up from nothing after the war and plastered the skyline with whatever was immediately needed, not what was aesthetically optimal. Daily Fuji-viewing became shuttered by progress.

My view out back is very congested. I have to edit out all the obstructions in my head to enjoy the elegance of the sun setting behind its poetry-inspiring slopes. Before my vision reaches Fuji, I have to de-select the neighbor’s house, a tangle of electric power lines, an ironwork scaffold for the lines, baseball field lights and a couple of high-rise apartment buildings in the distance.

My very first view of Mount Fuji was from a train passing by, and I was shocked to see the factories in the plains below, puffing out smoke. You don’t have to be a nihilist poet to figure out the symbolism. In many ways, the irony of that first impression has remained.

By this point in Japan’s development, there are hardly any straight shots of Fuji left. Advertising photos and documentary footage has to be doctored to remove the clutter. Of course, you can travel to one of the gorgeous mountainous lakes that surround Fuji like a necklace. But that means going on a special trip.

What remains most is the memory of Fuji as it once was, even though that memory comes in glimpses, fixed-up images or in-head editing. Fuji has become an image first, one that can be seen only indirectly, or in pieces, never whole. Mount Fuji seems to rise as much from past images as from the plains below.

And maybe it was always so. The first mention of Fuji goes back to the Man’yoshu, the oldest collection of poems in Japanese from the 8th century AD. Nowadays, the poems have turned to advertising.

Maybe because of that, Mount Fuji always seems like it is keeping its distance from Tokyo. Or maybe Tokyo, knowing it can’t compete, keeps its distance from Fuji.

But just the same, I’ll settle for my view of Mount Fuji out back. I gaze out at the slope, mistaking it for clouds on hazy or rainy days, and feel that it always comments, like a quiet relative, on the mega-city of Tokyo, reminding me that as amazingly huge and intriguingly developed as Tokyo is, there is always something else competing for our wonder.

New Reviews for Beauty and Chaos

“Beauty and Chaos is a rare gem of exploration that holds the ability to sweep observer/readers into a series of vignettes that penetrate the heart of Tokyo’s fast-paced world. Anyone planning a trip to the city (and many an armchair reader who holds a special affection for Japan) must have this in hand – and, in mind. Very highly recommended.” — D. Donovan, Senior Book Reviewer, Midwest Book Review

“Every small thing that makes Tokyo what it is gives the book a unique and special tone. Whether it is the cherry blossoms, the bars and restaurants, the standing libraries or clothing, the author has researched the place well and revealed to readers a Tokyo not captured so intensely by travelers. The author’s love for the city is evident in the manner in which he has explored the place and soaked up every small detail that covers everything about life in Tokyo. It’s a good book to read before traveling to the city. An exciting book that takes readers on a sightseeing trip of Tokyo, the place, its culture and essence.” — Mamta Madhavan for Readers’ Favorite

New Reviews

New Reviews for Beauty and Chaos

“Beauty and Chaos is a rare gem of exploration that holds the ability to sweep observer/readers into a series of vignettes that penetrate the heart of Tokyo’s fast-paced world. Anyone planning a trip to the city (and many an armchair reader who holds a special affection for Japan) must have this in hand – and, in mind. Very highly recommended.” — D. Donovan, Senior Book Reviewer, Midwest Book Review

“Every small thing that makes Tokyo what it is gives the book a unique and special tone. Whether it is the cherry blossoms, the bars and restaurants, the standing libraries or clothing, the author has researched the place well and revealed to readers a Tokyo not captured so intensely by travelers. The author’s love for the city is evident in the manner in which he has explored the place and soaked up every small detail that covers everything about life in Tokyo. It’s a good book to read before traveling to the city. An exciting book that takes readers on a sightseeing trip of Tokyo, the place, its culture and essence.” — Mamta Madhavan for Readers’ Favorite

March 1, 2015

Learning to Love the Crowd

Walking around Tokyo one of the first days of January, I decided to veer away from the crowds. Instead of spending more money on sales, sake or noodles (the holy triumvirate of the new year in Tokyo), I thought I’d store up some karma by restfully escaping to one of Tokyo’s greatest shrines, Kanda Myojin.

I thought the shrine would be a quiet respite from the shopping and indulging going on throughout the rest of the city. I figured I’d waltz through the food stalls, bow to the Shinto gods, take a photo or two and then train home, nice and quiet. Those Shinto gods, hidden away behind hanging screens and latticed doors, know how to bring in a crowd, it turns out. A short stop turned into a two and a half hour expedition.

The line into the shrine, several hundred meters of humanity, stretched along a major road down a slope not far from Ochanomizu station. The line, exactly six people across, was formed, and re-formed, by police and shrine attendants using a bullhorn, guide ropes, two-meter tall signs and sharp glances of menace and disquiet. A long line of people is not easy to control.

Or wouldn’t be, except Tokyoites are well trained in lining up, waiting patiently, and crowding together. For two and a half hours, no one complained. I kept my irritation to myself. It was amazing to be in the longest, widest line of my life. Six people wide, it was more of a moving mass than a line. Not even airport security lines could compete with this.

The line moved slowly in between long pauses at checkpoints until room ahead opened up. Everyone inside was, after all, praying for good wishes for the New Year, and it would be impolite to hurry them. No one, I guess, was particularly religious, but believing or not believing in the Shinto gods was not the point. The point was being in the line.

The pleasure was soaking in the buzz of everyone talking at once outside together and gazing, rather carefully and repeatedly given the slow pace, at the line of people ahead and behind, at the bright-lit food stalls, and breathing in the mingled smells of sizzling food. Once we got closer, bright red shrine buildings surrounded a huge open area into which the line spilled like a river into a lake.

On one side, a lion dance pranced and twisted to traditional Japanese music. On the other, female shrine attendants sold omamori (magic charms), the greatest variety I’d ever seen, over one hundred different kinds, and price levels. You need variety when you have that many people.

On one side, a lion dance pranced and twisted to traditional Japanese music. On the other, female shrine attendants sold omamori (magic charms), the greatest variety I’d ever seen, over one hundred different kinds, and price levels. You need variety when you have that many people.

An hour into the approach and everyone still waited patiently. A few people edged out of the crowd when a toilet came into view on the left hand side. How many lines do you need to take a toilet break? One or two people had to use their cellphones to find their friends and family again in the forward rolling tide.

Tokyoites, I realized, love being together in a huge group. There is comfort and security in a massive group like that. It’s so amazingly, intensely human.

And it’s exciting. Whether it is a rush hour train, a shrine at new year, a busy train station exit, or a bargain sale, the constant, close presence of lots and lots of people makes going anywhere in Tokyo a reassurance and reward, especially when they are neatly lined up.

I joined the line when it was still light, but by the time I got to the open square in front of the shrine, the sun had set and the moon was up. Alone in that same huge space on some non-holiday, it would have felt otherworldly, but with the thousands of other people crammed in there, it felt very worldly, powerfully human and down-on-earth.

I joined the line when it was still light, but by the time I got to the open square in front of the shrine, the sun had set and the moon was up. Alone in that same huge space on some non-holiday, it would have felt otherworldly, but with the thousands of other people crammed in there, it felt very worldly, powerfully human and down-on-earth.

The excuse was to toss a few coins to gods most people scarcely believed in and offer a hopeful prayer for the New Year. But really, that is not what everyone was doing at all.

We were all immersing ourselves in the power and energy of a huge group of people, standing together, looking up at the moon, looking around at the shrine, and at each other, creating a massive hum of conversation and wrapping ourselves in anticipation. The main purpose of that open square is to be filled up with people at New Year. This was hardly ethereal, invisible religion; it was humanism, and lots of it.

Part of the thrill of Tokyo is that repeated merging into a group, being part of it, but also apart from it. Living in Tokyo is a constant dipping into throngs of people, to come out reenergized by the special beauty and intense humanity a crowd creates. In Tokyo, being alone is its own special pleasure, too, but one that is heightened by the crowds all the rest of the time. Tokyoites love a crowd, and maybe for all the right reasons.

December 16, 2014

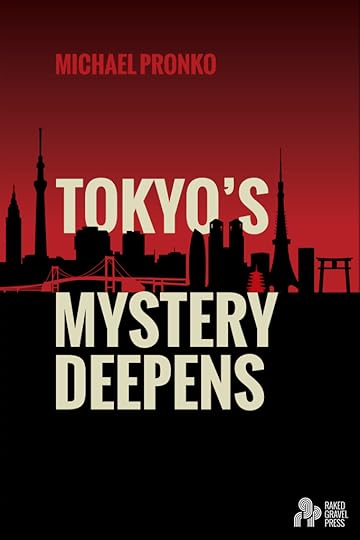

Next Book Out!

My next book is out on Kindle, available on Amazon.everycountryintheworld, as well as most other eBook eBookstores.

What happens when large bugs get trapped on crowded Tokyo trains? How does allergy season affect Tokyo’s millions? Ever wonder why Japanese love to take photos together or how everyone feels during rainy season? How is Tokyo made so compact and made as much from imagination as from concrete and steel?

Tokyo life is equal parts trial and joy. This collection offers up essential skills for living in the vastest, most crowded city in the world—sweating politely, suffering noise and glancing in mirrors–and muses over the minutest of daily details—window flowers, eye contact and small gestures of thanks.

If you’re traveling to Tokyo, these essays point toward the undercurrents of life and if you’ve ever considered visiting Tokyo, these essays will give you more reasons to go. If you live in Tokyo, you know all this, but you can always know it again. Tokyo’s Mystery Deepens taps into the enigmatic sides of Tokyo with humor, delicacy and a large dose of healthy confusion.

Click here for Amazon.com (English)

Click here for Amazon.jp (English)

It’s also available in Japanese as: トーキョーの謎は今日も深まる

Click here for Japanese version

December 12, 2014

Warhol’s Ghost Cans

Walking along the street, I was accosted by cans. What dreams I have of you tonight, Andy! In Tokyo, pop art, art, pop all flows together. The Japanese says, “Today Only,” which seems even more fitting for a pop art reconstruction. Did the store clerk take a course in American Art at college? I assume so! Who else would haul all those cans out to the front and set them up in the morning, and then haul them back inside at night when the store closes? Only an art lover!

November 7, 2014

Reviews

Reviews of Beauty and Chaos

“Japanese who are used to Tokyo are caught off guard by his conclusions derived from careful observation, and are struck dumb…Tokyo, the city we are so careless of, suddenly starts to become glorious. It is a wonder!” Chunichi Shimbun (Newspaper) (translated from Japanese)

“Giving up the bias and seeing the city with completely different standards, you will see the unexpected, attractive face of Tokyo. This book is a guide for rediscovering Tokyo that lets us see the city with unique new features.” Nikkan Gendai (Newspaper) (translated from Japanese)

“This is a book that surely makes humorous and philosophical analysis of Tokyo. It makes us understand ‘We are living in the most unique city in the world, which is certainly worth living in.’” Masaaki Tsutsui (Professor and author) (translated from Japanese)

“This book focuses on surprisingly small scenes of Japan which are unnoticeable to Japanese. The essays give us fresh discoveries with warmth and gentleness.” Reader (translated from Japanese)

“This book focuses on surprisingly small scenes of Japan which are unnoticeable to Japanese. The essays give us fresh discoveries with warmth and gentleness.” Reader (translated from Japanese)

“Regarding “The Way of the Bag.” The story you pointed out on “Kamibukuro” was perfect! I agree and that’s the way I do in everyday life. I want to tell you to thank you that you understood Japanese’s feeling.” Reader (originally sent in English)