Michael Pronko's Blog, page 22

August 9, 2015

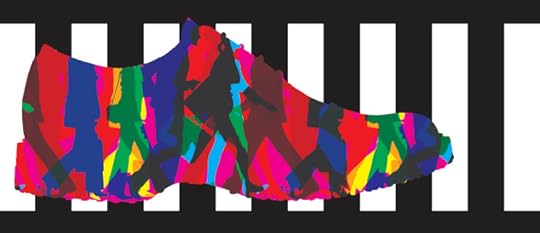

My Toe On Tokyo

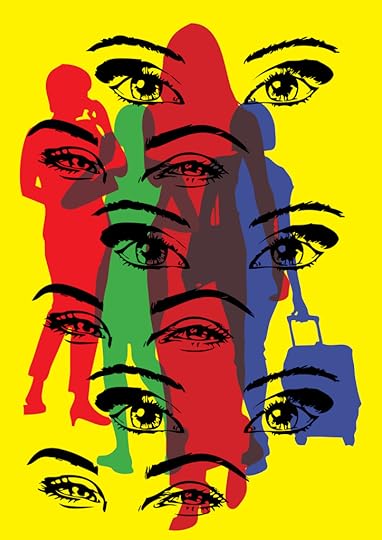

Illustration by Marco Mancini

Illustration by Marco ManciniA few weeks ago, I accidentally smashed my foot against the bookshelf in my hallway at home. My two littlest toes, and then my foot, turned blue, then purple, then green. I iced it, took aspirin and elevated it. It was another end-of-the-semester exhaustion-induced injury, the worst one, it turned out, ever. When I had to proctor final exams a couple days later, my toes still throbbed with pain. So, I taped it up, loosened my shoestrings, doubled the dose of ibuprofen, and headed to work. From that day, my attitude towards Tokyo changed completely.

The great Japanese film director Yasujiro Ozu was famous for looking at the lives of Tokyoites from low-position camera angles, as if watching events while sitting down on the tatami. My new point of view on Tokyo went even lower, right down to the ground. From the point of view of my little toes in great pain, Tokyo became a different city altogether.

First, I noticed the ground. Tokyo is not a flush, level city. The city is a mish-mash of uneven sidewalks, irregular stairs, and slippery floors. Each provided a different type of pedal agony. I became aware of every little bump. Even the yellow bumpy pathways for blind people made the bruised bones in my foot contort with pain. American cities are designed to accommodate the automobile, but Tokyo is designed around human feet!

And there are a lot of feet in Tokyo, all of them suddenly threatening. I realized any one of thousands of other feet could bump my tender toe. I kept edging away from people, desperate to leave some space between them and my second smallest right toe, the one that really hurt. Women in high heels no longer seemed so sexy, but like foot-stomping menaces, their heels like threatening little kendo sticks. I kept looking down, checking the proximity of their feet to mine and the toughness of the leather of their shoes.

As if to really test me, one day the Chuo Line trains were late. Typically, that means the next train becomes doubly loaded, and the next triply, and so on, depending on how many trains late things run. But with my toe in pain, that meant triple the danger. So, instead of plunging in as usual, I waited. But the next two trains were also packed, and I knew the rest would be, too, so I decided to risk it.

Usually, when I get on a super-crowded train, I grab a handhold over eh door, plant both feet and back-push on. But this time, with only one good pushing foot, I was unmanned. I had to wiggle weakly into place, hopping slightly and twisting clumsily.

But then, as the doors closed, it dawned on me, I could lift my sore foot up from the floor safely, like a flamingo, and the surrounding pressure of everyone around me would hold me securely in place. For once, I was thankful of the crowd.

That week, I tried not to limp too obviously when a pretty girl walked by, but the rest of the time, I clung to handrails like a drunken man. I took wide berths to see around corners, kept my right foot out of traffic, and searched ahead for escalators and elevators. I could no longer deftly avoid oncoming people, since I couldn’t pivot on my right foot. Instead of neatly swerving while maintaining my pace, I had to stop from time to time to let someone pass.

I had long since learned the Tokyo skill of moving like a school of fish; but suddenly, I was no longer part of the flow, but an un-Tokyo-like obstacle! Me, the perfectly trained commuter! All my hard-won crowd motion skills were for naught. Lurching through the crowds like Frankenstein, I grasped fully just how much wear and tear Tokyo puts on the 26 bones of the human foot.

I understand now why Tokyo has more shoe stores than any other kind! Finding the right shoes means being able to negotiate the city in the way you want. Not having the right shoes means you are not able to live as you like. In Tokyo, “I walk, therefore I am.”

After slowing down, I noticed an entirely new city—a slow-paced one. I saw older people ambling through places where I used to zip along. I saw people strolling, in no hurry whatsoever, looking around. I never before noticed all the people who plan their day around less crowded trains, like the 11:32 express I discovered I could get a seat on! I joined a new Tokyo group—the non-rushers.

There were lots of Tokyoites who were not in a big hurry, who didn’t clinch their buttocks and surge every forward. Plenty of people ambled calmly, almost sweetly. I just had never seen them before. The slow-paced Tokyo had been hidden from my view because I was always going way too fast.

Now that my foot is recovered, more or less, I’m not so sure I want to go back to high speed Tokyo. I kind of like the slower pace. I can see the city differently, and feel it much more deeply, even if, from time to time, depending on how I step, I still feel it a bit painfully.

Click on the link below to download the essay in PDF format.

June 12, 2015

City of Eyes

The other day, for the first time, a young woman on the train won the contest of “who will look away first.” In the past, I could always stare longer than anyone in Tokyo, but this Tokyo woman outstared me. I felt surprised, and maybe a little humiliated, that she could hold the eye contact longer than me–a westerner!

It was a clear case of ocular disempowerment, but it wasn’t always like that. When I first came to Tokyo, shopping, teaching or just walking around, I felt bewildered because no one met my eyes. Of course, I knew that in Asian countries, eye contact, like other body language, carries vastly different meanings than in America. Still, when eyelids would clamp down, I felt like the human element of the city was veiled and hidden away from me. It was hard to get a clear look into the heart of the city since the path through people’s eyes kept getting blocked.

These days, though, Tokyoites’ eyes seem as comfortable with western as with eastern eye contact rules. Whenever I make a purchase or look around on the train, people do not look away like they used to. Their eyes linger on mine as they hand me my bag, sit across from me on the train, or cut in front of me up the escalator. Tokyoites have always been masters of the side-glance and the stolen glance. But these days, Tokyoites are starting to master the direct stare, too.

I suppose some of this change comes from more Tokyoites going abroad. I can almost always tell when Tokyoites have spent a lot of time overseas from their eyes. In the same way foreign words have crept into the Japanese language, foreign eye contact has crept in, too. Some Tokyoites’ eyes holler out, “Hey, how ya doin’?” To determine time spent abroad, eye-contact duration is as accurate as any English language test!

Some people might interpret this is a loss of politeness. But it signals a big change in attitude. Keeping one’s eyes cast downward used to express social position and respect, so the current directness may seem lacking in delicacy and courtesy. When I order a coffee at the foreign-owned chain stores invading Tokyo, I’m startled by the way young part-time workers look right into my eyes. It makes me think, “Where am I? New York?”

Yet, though it might sound strange, but I feel somehow like Tokyoites’ eyes have been freed! They can look wherever they like for however long they want.

Unfortunately, though, some Tokyoites probably feel they can look more directly because they are safe inside the technological insulation of their cellphone and earphones. For some of them, I guess, I’m just another passing image. Looking at me is about the same as looking into the eyes of a close-up of Johnny Depp (though arguably less handsome) on their video screen. They may be looking more directly, and for longer, but not any more deeply. For some of those people, eyes are just an image of eyes, nothing more.

Usually, though, for most eye-contact-makers, I think it’s much more that. Increasing eye contact shows people are not retreating deeper inside themselves, but coming out a little more. Tokyo is, after all, a safe city, with people around all the time. For me, this increased eye contact shows an increasing comfort with other people, without any loss of civility. My students used to stare down at their desks so hard I thought there was something wrong with me, but these days, they are not afraid of confirming what they’re hearing, or what they want to say, through eye contact.

Even though we never say a word, the eyes I meet are ones filled with curiosity and a little warmth. They want to know what I’m doing there, I imagine, and let their eyes linger a bit to find out. In Tokyo, it’s always easy to look away, so I love these brief moments of ocular intimacy as I wander through the passing thousands of people every day. The increased eye contact shows people are unafraid to meet the inner world of some stranger in the middle of the city, even if for only a moment.

There’s a lot to see in Tokyo, but despite all the attractions, the brief, little moments of eye contact offer beauty and intensity. So different than observing another building, reading another menu or perusing another purchase, Tokyo eyes express unfathomable meanings. What could be more beautiful and mysterious than human eyes? What could be more human? Tokyo has a lot of eyes to look into!

There’s often a moment in the rush of Tokyo when I catch someone’s eyes and feel stirred by some sympathy and connection that I can’t quite name. That moment, when eyes touch eyes, brief as it is, always recharges my human batteries. It reminds me that Tokyo is a city of human beings, whose most interesting achievement is what their eyes, in their own special silent language, have to say.

Silver and Gold

Beauty and Chaos and Tokyo’s Mystery Deepens both received a Gold Award for Creative Non-fiction Essays and a Silver Award for Travel Essay in the annual eLit Book Awards 2015.

Beauty and Chaos and Tokyo’s Mystery Deepens both received a Gold Award for Creative Non-fiction Essays and a Silver Award for Travel Essay in the annual eLit Book Awards 2015.

While it’s always painful to compete against yourself, it’s also nice to share with yourself. The two books, released late in 2014, tied for first place in the Essay/Creative Fiction category and tied for second place for Travel Essays.

The annual awards are held by Independent Publisher Magazine. Their eLit Book Awards are dedicated to “illuminating digital publishing excellence.”

Tied for Gold Creative Non-Fiction Essays 2015

Tied for Silver Place Travel Essays 2015

Warhol’s Ghost Cans Redux

Walking along the street, I was accosted by cans. What dreams I have of you tonight, Andy! In Tokyo, pop art, art, pop all flows together. The Japanese says, “Today Only,” which seems even more fitting for a pop art reconstruction. Did the store clerk take a course in American Art at college? I assume so! Who else would haul all those cans out to the front and set them up in the morning, and then haul them back inside at night when the store closes? Only an art lover!

I posted this Ghost Cans in December, mulling over Warhol’s influence on the postmodern attitudes of Tokyo, and then the other night I ran into this guy not far from where the cans had been, in Kichijoji. I surreptitiously snapped a shot of his back, and then asked him if I could take it from the front. He was out drinking with his brother, sister-in-law, and nephew, none of whom showed the least Warhol-ian influence. They thought it funny I liked the jacket, which he didn’t seem to like too much himself. In fact, I’m not sure I liked the jacket exactly, but I liked the idea of it, and that’s what counts.

May 25, 2015

Expensive City, Free Book

Tokyo is one of the most expensive cities in the world, but you can get some great insights into the city for free!

Tokyo is one of the most expensive cities in the world, but you can get some great insights into the city for free!

Now, for a limited time, the e-version of Tokyo’s Mystery Deepens will be available for free at selected online e-book retailers!

Tokyo! Mysterious? Baffling? Unknowable? In these essays, the biggest city in the world comes a lot deeper and lot less mysterious!

For the Amazon version (not free), check out these links:

Click here for Amazon.com (English)

Click here for Amazon.jp (English)

It’s also available in Japanese as: トーキョーの謎は今日も深まる

Click here for Japanese version

This special Giveaway ends soon, in just a couple weeks, so pick up a free e-book copy today at the following fine stores:

Click here for Barnes and Noble

Click here for Story Cartel (you can sign up for more ebooks, too!)

And you can get the book for free on iTunes books, too!

Japanese version available from KADOKAWA Publishers as: トーキョーの謎は今日も深まる マイケル・プロンコ (著)

And if you happen to write and post a review after reading, I would be thrilled! Thanks in advance and happy reading!

May 7, 2015

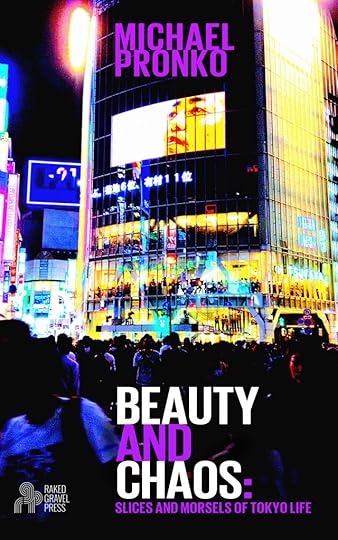

SPR Review of Beauty and Chaos

Review: Beauty and Chaos: Essays on Tokyo Life by Michael Pronko ★★★★★

Posted by: James Grimsby April 8, 2015 in Book Reviews, Latest Book Reviews

Beauty and Chaos: Essays on Tokyo Life (also subtitled as Slices and Morsels of Tokyo Life; full title 僕、トーキョーの味方です in Japanese) is a collection of writings by Michael Pronko on his experiences of the past 15 years living and working in Tokyo, originally published in Newsweek Japan, collected together here.

Born in Kansas City, and traveling across the world to places like Beijing, Pronko sets his view on Tokyo with the eyes of a writer well-traveled, but with an American-raised core to his ideas, his once-fresh eyes, and his general outlook.

These aspects are important in the consideration of Beauty and Chaos as Pronko evaluates his new home through a mixture of being someone from the outside looking in, and as someone now rooted on the inside of the Tokyo culture. These kinds of working contradictions make up the core theme of the collection, painting Tokyo as a city full of them: both fast-paced and serene; traditionalist and cutting edge; beautiful and chaotic.

A palette of mixed binaries and oppositions is how Pronko paints the city, and does so vividly. The book endeavors to capture the subtle and the obvious in what makes Tokyo such a rich, appealing place to visit or live, and does so poetically. From the small pauses in the daily rushes with a drink from a vending machine, to the larger attractions and the blaring neon that informs the cover, all aspects form a series of images of the city that come together as a wonder-filled narrative of the area.

The book is equal parts journal and travel guide (travelogue, debatably), though mostly it stands as neither. The book is informed by experience, and describes emotions and phenomena common to the Tokyo lifestyle over must-see spots and travel tips. Furthermore, the book is in no way something made exclusively for those who have experienced life in Tokyo, as it maintains itself in a very easy to understand way, even to a complete foreigner.

The translation from original Japanese Newsweek for English reading is very successful, complete with gentle re-translations of common terms (along with a glossary, just in case) that fit the flow of every haiku-like sentence. Pronko illustrates his points with marvelous skill, most impressive in that his writing carries a distinct air of Japanese linguistic habits while remaining skillful and succinct in English. Truly the book is as the city it describes, an eclectic mix and a contradiction in of itself. It is clearly defined by its author without being so tied to his specific personality or life that there is a loss of purity to the experience.

For readers interested in Tokyo, in modern Japanese life and culture, or in simply reading a beautiful set of essays of a place you may or may never have been yourself, Beauty and Chaos is a spectacular read. Its essays are long enough to be cohesive and provocative while remaining short and sweet, never rushing points but never falling too far off track. The collection is masterful and unique, and well worth the time to read through.

Midwest Book Review of Beauty and Chaos

by Diane Donovan

Anyone with an interest in Tokyo will want to consider the fifteen years of experience that’s gone into Michael Pronko’s Beauty and Chaos, an essay collection that comes from a professor with much experience in the city, who can bring it to life through flowery written descriptions.

Just what is so special about Beauty and Chaos, and what sets it apart from your usual Japanese cultural observation or travelogue? Plenty! For one thing, many of the essays center on the ironies and inconsistencies of Tokyo. Readers thus gain a much clearer vision of the city’s incongruities and attractions than your usual where-to-stay and what-to-see one-dimensional survey. Take train platforms, for example: “Such adrenaline-charged situations are rare, though. Typically, platforms most often offer space for solitude. Like Giacometti statues, thin and crinkly, surrounded by vast open space, the platforms are filled with people standing utterly alone. The occasional crowd around them makes no difference, they are framed by a huge open area that creates an anonymity and loneliness like no other place in the city.”

Under Pronko’s hand, something as simple as eating with chopsticks becomes not just a cultural observation but a dance of understanding and insight: “The chopsticks enact the food, display it, and energize it. Everything wiggles in the air. This re-created motion is clearest especially when eating uncooked foods, which are so common in Japan, and complement chopsticks well. Pieces of fish, especially fish, become re-animated by the motion towards the mouth. The sashimi lives swimmingly again for a moment before being tucked away.”

Just with these few passages, lifted laboriously from a plethora of wealthy, full-bodied writings, one can see that to truly know Tokyo and plan for a visit there, Beauty and Chaos should be right there at the top of the travel guides and trip planners. Without it, it would be all too easy to miss the city’s unique attractions and unique cultural attributes – and that would be a shame.

Beauty and Chaos is a rare gem of exploration that holds the ability to sweep observer/readers into a series of vignettes that penetrate the heart of Tokyo’s fast-paced world. Anyone planning a trip to the city (and many an armchair reader who holds a special affection for Japan) must have this in hand – and, in mind. Very highly recommended.

Reader’s Favorite Review of Beauty and Chaos

Reviewed by Mamta Madhavan for Readers’ Favorite

Beauty and Chaos – Essays on Tokyo Life: Slices and Morsels of Tokyo Life by Michael Pronko is an exciting book that sheds light on Tokyo. The book takes readers on a trip into the heart of the city, exploring areas in and around Tokyo that add to its exotic charm. The author has captured the beauty of the city, sharing all the nuances and minute details with readers. The book makes readers familiar with everything about Tokyo and the description of the place is so evocative and visual that it is like being on a sightseeing trip there. The book also reveals the author’s love and passion for Tokyo.

I enjoyed the book thoroughly because it not only captures the beauty of the place, but also the culture and essence of the society. Every small thing that makes Tokyo what it is gives the book a unique and special tone. Whether it is the cherry blossoms, the bars and restaurants, the standing libraries or clothing, the author has researched the place well and revealed to readers a Tokyo not captured so intensely by travelers. The author’s love for the city is evident in the manner in which he has explored the place and soaked up every small detail that covers everything about life in Tokyo. It’s a good book to read before traveling to the city. An exciting book that takes readers on a sightseeing trip of Tokyo, the place, its culture and essence.

Bookbag Review of Beauty and Chaos

Adapting a Buddhist metaphor, Michael Pronko declares that ‘writing about [Tokyo] is like catching fish with a hollow gourd.’ In other words, it is an elusive and contradictory place that resists easy conclusions. Anyone who has seen the Bill Murray film Lost in Translation will retain the sense of a glittering, bewildering place that Westerners wander through in a daze. A long-term resident but still a perpetual outsider, Pronko is perfectly placed to notice the many odd and wonderful aspects of Tokyo life.

The essays in this book, most of them few-page vignettes, originally appeared in Newsweek Japan, and were first collected for publication in 2006. A second volume, Tokyo’s Mystery Deepens, was published in 2009. Pronko’s topics are varied and surprising. He notices the kinds of things that might be taken for granted by the Japanese and overlooked entirely by visitors, such as the prevalence of vending machines and bottle displays or the popularity of store bags, loyalty cards, and truck deliveries. He takes readers to unexplored gaps, like those between properties – where cats and rubbish collect to ‘create an atmosphere of loneliness.’

Most people think of Japan as an orderly, rule-driven society. Pronko acknowledges that Tokyo life is governed by timetables – ‘Clocks hang everywhere and few wrists go watch-less … [people] relish a kind of cleanliness of time. Open time seems sloppy and confusing’ – but also notices that the Japanese are often late or waste time. Likewise, a national obsession with maps does not equate to logical spatial arrangements: ‘Tokyo is NOT a comforting city of straight, easy-to-follow lines … Yet, on maps, the city seems to make perfect sense.’

Similarly, the Japanese are not always what they seem. It is true that they are secretive and respectful when it comes to money, and they are usually reserved in terms of physical affection. However, all that goes out the window for the month of December, when bonenkai parties dominate.

These pieces feel flowing and natural, perhaps because many arose simply from walking around, people-watching. Pronko sees a woman in head-to-toe pink and ponders how unusual the colour is in the often ‘sedate’ Japanese wardrobe. He delights that mobile phones have not totally replaced reading on trains. Indeed, the practice of tachi-yomi (reading standing up) proves that nothing will keep the Japanese from reading. In-your-face T-shirt slogans like ‘THIS AFFECTS YOU’ are another constant source of amusement.

My favourite essays were ‘Singing in the Rainy Season’ and ‘The Love of Small Places’. Despite the inconvenience, Pronko finds theatrical beauty in days of torrential rain: ‘Umbrellas turn the sidewalks into a pumping carousel of coloured half-spheres. Everyone sways like jugglers in a huge rainy parade.’ The latter essay considers miniaturisation: haiku, bonsai, and interior design. Like Alain de Botton in The Architecture of Happiness, Pronko asserts that design ‘shapes how one experiences the environment.’ Both of these pieces (and Part Five in general) testify to Pronko’s facility with visual art.

My main point of criticism is that the structure of the collection is sometimes arbitrary. Two essays that would have been helpful at the very start, ‘How I Ended Up Here’ and ‘Japan and Me,’ come later on. These give background information about Pronko growing up in Kansas City, Kansas and moving to Japan on a lark. Combined, those two essays would have made a good introduction. The piecemeal effect of magazine writing means that a few pieces feel redundant. For instance, soon after an essay on stairs, do we really need one about escalators? Also, given the subtitle, I might have expected more about Japanese cuisine.

Small quibbles aside, I recommend these poetic, whimsical essays. Pronko uses fresh metaphors, like ‘Tokyo often seems like a fickle teenager, moodily swapping its clothes.’ Even after 15 years in Japan, he has more questions than answers, which seems an appropriately humble attitude for an outsider to take: ‘Tokyo drives me not towards well-defended conclusions, but towards open-ended musing … I read the city by writing.’

–Rebecca Foster, The Bookbag

Kirkus Review of Beauty and Chaos

An American expatriate’s perceptions of Tokyo, from its places to its moods.

In this essay collection, which was previously published in Japanese, Pronko (The Other Side of English, 2009, etc.) leads readers through his adopted hometown, one vignette at a time. The narrative moves through the city’s physical space, following maps and train lines, as well as what it means to be a Tokyo resident. For example, he covers the reuse of shopping bags and the nuances of bag quality and how one must run the last few feet to catch a train. Pronko sees metaphors throughout the city (“Drink vending machines are like the little cups of water handed to marathon runners as they pass by”) and has an experienced observer’s eye—far from jaded but never squealing with delight when discovering new facets of his host culture. His essays describe the elements of a Tokyo existence in a respectful tone, taking note of the details that make the city unique without exoticizing them. It neither sets up Tokyo as a foil for the shortcomings of Middle America nor devolves into complaints about crowds or the high cost of living in another country. The author’s prose is polished, with pithy insights (“My body adapted to Tokyo long before my mind did”), elegant descriptions (“High heels, a summertime addiction, are thin as chopsticks but loud as kendo swords”), and cultural frames of reference (“Japanese pilgrimages…involve walking around and around a circling route of temples. Western pilgrimages are pretty much straight lines right up to the holy spot and then straight back home”). The result is a clear-eyed but affectionate portrait of a city that reaches beyond simple stereotypes. It will draw in readers who have no experience with Japanese culture, but it also highlights details of daily life that will have readers in the know chuckling with recognition.

An elegantly written, precisely observed portrait of a Japanese city and its culture.

April 20th, 2015